Steve Blank's Blog, page 27

April 7, 2016

Entrepreneurs are Everywhere Show No. 27: Brandon Bruce and Jack Sundell

When your customers are grabbing your Minimal Viable Product out of your hands, it’s time to launch the product.

The latest guests on Entrepreneurs are Everywhere explained why.

The radio show airs on SiriusXM Channel 111 (weekly Thursdays at 1 pm Pacific, 4 pm Eastern). It follows the journeys of founders who share what it takes to build a startup – from restaurants to rocket scientists, to online gifts to online groceries and more. The program examines the DNA of entrepreneurs: what makes them tick, how they came up with their ideas; and explores the habits that make them successful, and the highs and lows that pushed them forward.

Brandon Bruce

Joining me in SiriusXM’s studio in New York were

Brandon Bruce, co-founder of Cirrus Insight software company

, co-founder of The Root Café farm-to-table restaurant

Jack Sundell

Listen to the full interviews with Brandon and Jack by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here.

(And download any of the past shows here.)

Clips from their interview are below.

Brandon Bruce is a co-founder of Cirrus Insight, a plugin for Gmail and Outlook that allows Salesforce apps to be used inside an inbox. Before starting Cirrus Insight, Brandon was director of gifts and grants at Maryville College, and operations manager of Rangefire Integrated Networks.

Brandon explained how he knew it was time to launch:

Brandon : … customers told us that it was ready. They said, “We know it needs more and we want more from it, but it’s ready enough and we find value from it.”

One customer found the website — they weren’t supposed to find it. … They put their credit card in and paid for the app. We said, “We’re not going to charge you yet. We’ll refund the money.” They said, “It’s OK, I’m going to buy it once it’s for sale so I’ll be your first customer.” That was a vote of confidence. We figured there’s a company behind the app.

Steve : You tested with customers, you got customer feedback, you listened … Your thought, “We need to fill out our feature set because our plan said so” (but customers said) “No you don’t. Features 1,6, and 12 are good enough now.”

Brandon : That’s exactly what they said. I’m glad that they did because it got us to market first; we captured a lot of mind share. People said, “Well, if you want Gmail and Salesforce, then Cirrus Insight is the app for you.

They were telling us, “This is what we need and want. These are the features we need and want. This is a great product and is saving us a lot of time and it’s getting better data in Salesforce. We can run better reports and it’s elevating the whole business.”

We thought, “Well, that’s a big win for them. There’s value there in the marketplace, so we decided to get it out.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Before opening The Root Café with his wife Corri in 2011, was in the Peace Corps. Stationed in Morocco he taught English and organized activities at an after school youth center. When he returned home to Arkansas, he volunteered at the Heifer Ranch in Perryville and quickly fell in love with producing and cooking fresh food.

The experience stoked a passion in him for opening his own café, but rather than jump in to the farm-to-table venture, Jack took three years to launch. He said it was time well spent:

Jack : We learned a lot about hard work, about the importance of working to build community, the importance of building capital on the front end and trying to stay out of debt. The real driver was that we wanted to fund the café without borrowing money, so we decided to spend these three years doing a capital campaign.

We would do things like fundraisers where we would just invite a lot of friends to come and they would donate to this project. We did canning and food preservation workshops. We did catering out of a church kitchen. We also did something we called the share campaign, which was a lot like a kick-starter or a crowd-funding campaign, where we basically pre-sold our food and promised that for every $10 that someone donated, we would pay them back with a meal once we opened.

Steve : So while raising money, you were running a branding and a customer-acquisition campaign. People knew you were going open a restaurant for three years?

Jack : Right! It helped us build a great mailing list. It helped us get our brand out there. It helped raise awareness of local foods in general, so all of those things turned out to be really great.

It also helped us create a network of farmers, which was another one of those things that we didn’t realize was important, but through all the catering work we had done and the food preservation workshops, we had connected with lots and lots of the farmers that deliver to Little Rock.

Steve : Those farmers are your supply chain?

Jack : Right. We purchase every week from 25 or 30 different farmers and producers and on an annual basis, maybe 50 or 60. There is no way that we would have had time to establish all those connections once we were in the trenches of actually opening a restaurant.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

—

Building a partner network was another crucial thing for Cirrus, Brandon said:

Brandon : People said a SAAS (Software as a Service) companies like ours, haven’t had a lot of success selling through partners. But it just made sense to us that partners could be like an extended sales team before we could afford to have one. We developed these relationships …

Steve : These partners sold your product for you because it complemented some of the other products they sold?

Brandon : Yeah. Our partners are Salesforce consultants. They’re implementing Salesforce and would tell the client, “This is the way to boost Salesforce. “You’re using Gmail or Outlook, and you’re scheduling appointments with customers on the calendar. That’s where you live, and all that data really needs to go into Salesforce and vice versa so you need Cirrus Insight”. … and those folks help drive a lot of sales for us. So we use a partner channel, we do telesales and we do a lot of email.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

A crisis showed Brandon and his co-founder, Ryan Huff, that they had achieved success:

… Ryan and I … both have young kids and we decided well, so far, so good. We’re about a year into building the company and let’s take the kids to Disneyland and, of course, it’s while we’re at Disneyland that it’s one of the biggest power outages in history took our app down as well as Netflix and Instagram and Foursquare and other far better-known apps down.

For 30 seconds or so, we thought maybe we’d have a breakout sales day because we had about 100 calls and then we figured, no, something’s actually wrong.

Meanwhile, our customers cared that Cirrus was down.

… We were at Disneyland on our phones with not a lot of ability to do anything. Not that we could have done anything back at the office either, because it was out of our control. That was a very challenging day. The silver lining to that was that the feedback that we got from the customers was stuff like “people have stopped working at the office because your site is down.” We thought, wait a second, Google is still up, Salesforce is still up. You can just work the way you did before but they said “no, it’s become such an ingrained part of our workflow and it’s so important, we won’t go back to the other way. Until the app comes back up, everyone’s going to kind of hang out.”

We thought, it’s a must-have application now for companies.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

—

Jack went the hands-on route to learn about the restaurant business:

Once we had figured out that we were going to go forward with the idea of opening a café, I worked in a couple of places in Little Rock that were really similar. Kind of the fast, casual model where you order at the counter, find a seat, they bring you your food. I picked a couple of those places in Little Rock that I thought would be good for learning my way around.

… (It was) a lot of trying to learn how orders happen, how did they make sure they had the food they needed to produce the menu every day, how did they make the schedule so that employees knew when to come to work.

… It was a huge learning experience…. Behind the veil of a restaurant there’s a lot of things that go on that once you see and you realize, “Gosh, that’s really a smart way.” It’s not that every restaurant reinvents the wheel. There’s almost never a situation where someone opens a restaurant without ever having had any contact. This is all knowledge that’s been passed down over generations.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

And he quickly learned that running an eatery is about far more than the food:

Jack : Really when we started there was this goal, and we did whatever felt right at each turn to reach it. If I had known, for example, when I was in college that I would be operating a restaurant some day, I would have loved to take some accounting and bookkeeping courses. It would be so helpful to know more about electrical and plumbing (because) anything that I have to pay someone $75 an hour to fix now, when it goes wrong, I’d love to be able to do that myself.

… (Also) it never even occurred to me to go to culinary school when I was in college or going to college, or getting out of college, but it’s fascinating, and there’s so many culinary schools that offer a great education, so I could have done that instead of just bouncing around with an undecided major in college. Then, I think it also really would have been helpful to identify employee management …

Steve : How many people do you have?

Jack : When we started, there were about four. My wife and me, and two employees, and now we’re at about 18. … We have a front of house staff, we have a back of house staff, so it’s just a really steep learning curve, how to attract, how to motivate, how to maintain great relationships with employees because really, if you think about it, employees are your ambassadors.

They’re your representatives all the time, and if you’re ever not going to be there, you have to trust that your employees are going to do the kind of job that you would do if you were there. Trying to teach that, trying to verbalize it, trying to instill it as a philosophy, we found it to be a really difficult thing.

It’s a challenge but it’s also really rewarding, and now we have really an incredible staff that we’ve built, it’s taken us four and a half years to get to this point. But we’re open today and I was able to come to New York to do this interview, so I think we’ve come a long way.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Listen to my full interviews with Brandon and Jack by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here. (And download any of the past shows here.)

Next on Entrepreneurs are Everywhere : Michael Mondavi, founder and coach of Folio Fine Wine Partners, and Magdalena Yesil, founding investor and board member of Salesforce.

Tune in Thursday at 1 pm PT, 4 pm ET on Sirius XM Channel 111.

Want to be a guest on the show? Entrepreneurship stretches from Main Street to Silicon Valley, from startups to big companies. Send an email to terri@kandsranch.com describing your entrepreneurial journey.

Filed under: Customer Development, SiriusXM Radio Show

April 4, 2016

Hacking for Defense (H4D) @ Stanford – Week 1

We just had our first Hacking for Defense class and the 8 teams have hit the ground running.

They talked to 86 customers/stakeholders before the class started.

(Because of the embedded presentations this post is best viewed on the website.)

Hacking for Defense is a new class in Stanford’s School Engineering, where students learn about the nation’s security challenges by working with innovators inside the Department of Defense (DoD) and Intelligence Community. The class teaches students the Lean Startup approach to entrepreneurship while they engage in what amounts to national public service.

Hacking for Defense uses the same Lean LaunchPad Methodology adopted by the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health and proven successful in Lean LaunchPad and I-Corps classes with 1,000’s of teams worldwide. Over 70 students applied to this new Stanford class and we selected 32 of them in 8 teams.

One of the surprises was the incredible diversity of the student teams – genders, nationalities, expertise. The class attracted students from all departments and from undergrads to post docs.

Before the class started, the instructors worked with the Department of Defense and the Intelligence Community to identify 20 problems that the class could tackle. Teams then were free to select one of these problems as their focus for the class.

Most discussion about innovation of defense systems acquisition starts with writing a requirements document. Instead, in this class the student teams and their DOD/IC sponsors will work together to discover the real problems in the field and only then articulate the requirements to solve them and deploy the solutions.

Hacking for Defense: Class 1

We started the first class with the obligatory class overview slides. (Most of the students had already seen them during our pre-class information sessions but the class also had team mentors seeing them for the first time.)

If you can’t see the slides click here

Then it was time for each of the 8 teams to tell us what they did before class started. Their pre-class homework was to talk to 10 beneficiaries before class started. At the first class each team was asked to present a 5-slide summary of what they learned before class started:

Slide 1 Title slide

Slide 2 Who’s on the team

Slide 3 Minimal Viable Product

Slide 4: Customer Discovery

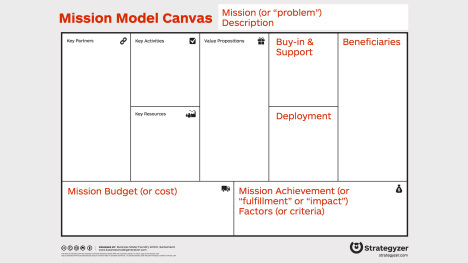

Slide 5: Mission Model Canvas

As the teams presented the teaching team offered a running commentary of suggestions, insights and direction.

Unlike the other Lean Launchpad / I-Corps classes we’ve taught, we noticed that before we even gave the teams feedback on their findings, we were impressed by the initial level of sophistication most teams brought to deconstructing the sponsors problem.

Here are the first week presentations:

Team aquaLink is working on a problem for divers in the Navy who work 60 to 200 feet underwater for 2-4 hours, but currently have no way to monitor their core temperature, maximum dive pressure, blood pressure and pulse. Knowing all of this would give them early warning of hypothermia or the bends. The goal is to provide a wearable sensor system and apps that will allow divers to monitor their own physiological conditions while underwater.

If you can’t see the presentation click here.

Team Fishreel is trying to combat “Catfishing”; where someone is impersonating a specific person (i.e. celebrity), a person with a specific interest (i.e. Cake enthusiast) or an organization (i.e. Online book seller) or even an entire service being impersonated, like an online retailer or financial or IT services provider. The team is working with the intelligence community to develop a technique to score how likely it is that a given online persona is who they claim to be, and how that conclusion was reached.

If you can’t see the presentation click here.

Team Guardian is asking how to protect soldiers from cheap, off-the-shelf commercial drones conducting Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance. What happens when adversaries learn how to weaponize drones with bullets, explosives, or chemical weapons?

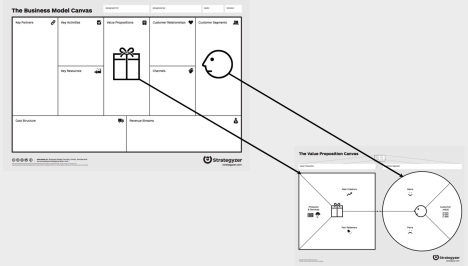

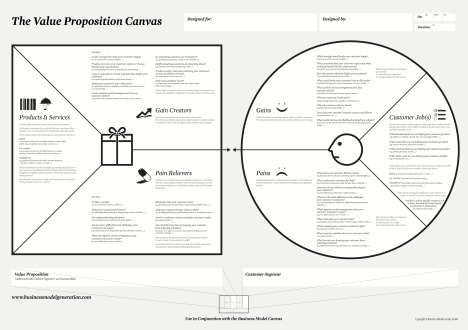

Slides 6 and 7 use the Value Proposition canvas to provide a deeper understanding of product/market fit.

If you can’t see the presentation click here.

Team Skynet is also using drones to to provide ground troops situational awareness. (Almost he inverse of Team Guardian.)

Slides 6 – 8 use the Value Proposition canvas to provide a deeper understanding of product/market fit.

If you can’t see the presentation click here.

Team LTTT (Live Tactical Threat Toolkit) is providing assistance to other countries explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) teams – the soldiers trying to disarm roadside bombs (Improvised Explosive Devices – IEDs). They’re trying to develop tools that would allow foreign explosive experts to consult with their American counterparts in real time to disarm IED’s, and to document key information about what they have found.

If you can’t see the presentation click here.

Team Narrative Mind is trying to determine how to use data mining, machine learning, and data science to understand, disrupt, and counter adversaries’ use of social media (think ISIS). Current tools do not provide users with a way to understand the meaning within adversary social media content and there is no automated process to disrupt, counter and shape the narrative.

If you can’t see the presentation click here.

Team Capella is launching a constellation of satellites with synthetic aperture radar into space to provide the Navy’s 7th fleet with real-time radar imaging.

If you can’t see the presentation click here.

Pre-Computing the Problem and Solution

As expected, a few teams with great technical assets jumped into building the MVP and were off coding/building hardware. It’s a natural mistake. We’re trying to get students to understand the difference between an MVP and a prototype and the importance of customer discovery (hard when you think you’re so smart you can pre-compute customer problems and derive the solution sitting in your dorm room.)

Mentors/Liaisons/DIUx Support

Besides working with their government sponsors, each team has a dedicated industry mentor. One of the surprises was the outpouring of support from individuals and companies who emailed us from across the country (even a few from outside the U.S.) volunteering to mentor the teams.

Each team is also supported by an active duty military liaison officer drawn from Stanford’s Senior Service College Fellows.

Another source of unexpected support for the teams was from the Secretary of Defense’s DIUx Silicon Valley Innovation Outpost. DIUx has adopted the class and along with the military liaisons translate “military-speak” from the sponsors into English and vice versa.

Advanced Lectures

The Stanford teaching team uses a “flipped classroom” (the lectures are homework watched on Udacity.) However, for this class some of the parts of the business model canvas, which make sense in a commercial setting, don’t work in the Department of Defense and Intelligence Community. So we are supplementing the video lectures with in-class “advanced” lectures that explain the new Mission Model Canvas. (We’re turning these lectures into animated videos which can serve as homework for the next time we teach this class.)

The first advanced lecture was on Beneficiaries (customers, stakeholders, users, etc.) in the Department of Defense. Slides 4-7 clearly show that solutions in the DOD are always a multi-sided market. Almost every military program has at least four customer segments: Concept Developers, Capability Managers, Program Managers, Users.

If you can’t see the presentation click here.

Each team is keeping a running blog of their customer interactions so we can virtually look over their shoulder as they talk to customers. From the look of the blogs week 2 is going to be equally exciting. Check in next week for an update.

Lessons Learned from Class 1

Talented and diverse students seem eager to solve national defense problems

Teams jumped on understanding their sponsors problems – even before the class

We’ve put 800+ teams through the NSF I-Corps and another 200 or so through my classes, but this class feels really different. There’s a mission focus and passion to these teams I’ve not seen before

Filed under: Hacking For Defense, Teaching

March 29, 2016

Entrepreneurs are Everywhere Show No. 26: Javier Saade and Hillary Hartley

The U.S. government is discovering that Lean innovation can help them serve the country better and faster.

The Small Business Administration and the digital services agency 18F are trying to help entrepreneurs build successful companies and the 21st century digital government.

The guests on today’s Entrepreneurs are Everywhere radio show explained how they’re working to do that.

The show follows the journeys of founders who share what it takes to build a startup – from restaurants to rocket scientists, to online gifts to online groceries and more. The program examines the DNA of entrepreneurs: what makes them tick, how they came up with their ideas; and explores the habits that make them successful, and the highs and lows that pushed them forward.

Javier Saade

Joining me on the latest show were

Javier Saade, former associate administrator for the U.S. Small Business Administration

Hillary Hartley, deputy executive director of 18F, a digital services agency inside the General Services Administration

Hillary Hartley

Listen to the full interviews with Javier and Hillary by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here.

(And download any of the past shows here.)

Clips from their interview are below.

Javier Saade was the U.S. Small Business Administration ’s Associate Administrator and chief of its investment and innovation programs.

Prior to his public service, Javier spent 20+ years in investing, management, entrepreneurial and public policy, starting as a strategy consultant at McKinsey and Booz, Allen and at Abbott Laboratories. He also co-founded three companies: a broadcasting network, Air America Media, a solar energy company, Atenergy and a branding agency, Brand Maestro.

Javier explained how the SBA helps drive entrepreneurship in the U.S.:

Javier : … the entrepreneurial engine of the United States is bar none the most efficient wealth creation and job creation tool that has ever existed. …

I headed up the programs that focused on high-growth businesses in the United States.

The U.S. government is the biggest spender and the biggest investor in research and development in the world. $140 billion this year, about half of it goes into very basic science research. (For example) we’re trying to discover the 111th periodic element, which you may not have a current application for. And some of it could be in development. For example, the department of defense saying, “We need a very thin plastic that stops bullets and we want it to be this thin.” So essentially, the government invests in both (research), and (development).”

Two of the entrepreneurial programs, which I managed is called the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR), and the Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) programs. Essentially the SBIR and STTR programs took ~2% of that $140 billion research and development budget and invested it in small businesses who want to commercialize this government investment in research and development. We give out between $2 and $3 billion a year for these startups as 5,000 and 7,000 grants to small businesses doing everything from advance composite materials, space exploration, to IT, mobile security, you name it. The goal is help these companies take their tech

…It is money extremely well spent. The way the program is structured is not dissimilar to how companies travel the capital formation path in the commercial world.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Getting things done in Washington, he says, is a challenge:

Javier : … For things to get done, the politics is something that was very difficult to get used to. …

Steve : Was even the Small Business Administration politicized?

Javier : Everything is politicized.

Steve : I would have thought this was kind of neutral, good for the country.

Javier: It’s neutral good for the country, but there’s always dissension, and that’s one of the things that, probably the only thing I did not like. … I loved the experience, I think it was an amazing experience to serve the country, to do things that are bigger than yourself. However I had 535 bosses – if you think about a company, the owners are represented by the board of directors. In the case of the company, it’s 320 million Americans that are represented by 535 (Congressmen). … so that was my board of directors.

Steve : How about the organization itself? Did you encounter organizational inertia?

Javier : Well … I was an appointee of the White House, and there’s always that rub … about … the professional managers of the government that at the end of the year you can’t incent them like in the private sector. … (and) you can’t fire them. You can’t … incent them with bonuses. You (are) very constrained as to what motivational tools you (have).

That said, again, just the experience I wouldn’t trade for anything in the world. There’s 28 million small businesses in the United States. While I was there … I touched tens of thousands of companies.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

—

Hillary Hartley is co-founder and lead creative at 18F, a digital services agency inside the General Services Administration. She came to the GSA as a Presidential Innovation Fellow in 2013, where she worked on the development of MyUSA.gov. Hillary has been working to make government more accessible and available online for nearly two decades, starting as a web designer for Arkansas.gov in 1997.

Hillary pointed out that there’s plenty of innovation taking place within the government:

Hillary : We are here to help the folks in every government agency trying their hardest to get really awesome stuff done, and perhaps they’re blocked because of budget, perhaps they’re blocked because they don’t have the staff (or) any number of blockers.

They can come to us at 18F and we can help them try to get their awesome idea off the ground. That’s the attitude we take, that we are really just here to help get the amazing things that the agencies are already working that aren’t done.

Steve : This notion of innovation and the U.S. government doesn’t typically come up in the same phrase.

Hillary : It has been referred to as an oxymoron (but) it’s not true at all. … Even if you think back to the first year of the presidential (innovation) fellowship, when this was just a hypothesis: could we get 15 to 20 folks from the private sector to come in and kick off some of these projects. Even then, the projects that agencies were pitching to that team were incredible. Folks across the federal government have incredible ideas and they’re trying to get some amazing things done.

Like I said, they often just are blocked in some way, perhaps they don’t have the employees to get it done, they don’t have the resources to get it done, they aren’t sure where to start, so we are here to help them figure out how to start.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Here’s how 18F works:

Hillary : 18F … is a consultancy. We are a team of digital services experts, about 160 currently to serve government agencies. … We’ve grown about 10x in a little over 18 months.

Essentially our work all starts about the same. Agencies approach us with an idea, with, perhaps, a product or a project that they’ve been kind of stewing on internally or maybe it’s just a big outside-of-the-box thing. …Our work takes primarily three directions: 1) Are we going to help them build the solution or 2) are we going to help them figure out how to buy it or 3) maybe get their current solution back on track?

… One of our most recent launches was with the FEC, the Federal Election Commission. It was a pretty exciting project because it encapsulates what we really want to do and what we like to do and what our goals are for this team.

The FEC came to us and said, “We’ve got all this data. We’ve got an enormous amount of open data, it’s really cool data but nobody comes to us for that data. Other groups like the Sunlight Foundation or Open Secrets, other groups are coming and downloading it, because it’s open data, it’s available for the public, and then they do cool stuff with it.” They wanted people to be coming to the mother ship for this data. We said, well, OK, you’ve got probably two problems, you’ve got a website that needs some help but also we want to lay the plumbing, we want to lay the foundation. We are a data-first and API-first team, application programming interface. You know, really wanted to lay the infrastructure for other people, including us, to use that data more effectively. The first thing we did was we built an API, an application programming interface.

Steve : So other people can suck out data from their site?

Hillary : That’s exactly right. There are something like 65,000 different end points within that data so everything we really were focusing on. … the FEC deals with campaign finance information, regulating and disclosing all that information.

Steve : You help people get access to all this government data … that the people who ran the website just hadn’t done before, either because of a lack of skills or a lack of time or a lack of expertise that you brought.

Hillary : That’s exactly right. We launched the API first and allowed a bunch of different researchers and organizations like the Sunlight Foundation and Open Secrets to grab that data and start doing interesting things with it. Then we went to work on building a search website for the FEC, completely redoing their interface to the data (so people can actually search) from FEC.gov.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Here’s how 18F fosters a culture of service:

Hillary : The culture has become so ingrained in me and it really is about service (and) community. The folks on the 18F team are empowered. They feel like they are able to just get things done.

On our website you’ll see the phrase, “Delivery is the strategy.” The way we are making the cultural change inside all the industries we work with is by shipping — by shipping code, by delivering the things that we’re working on.

And by doing that, we’re also shipping culture, we’re giving the agencies an opportunity to do something in a brand-new way — (for example) to participate in a design studio. To get pencils out and sketch along with us. To go through a deep dive as some sort of daylong workshop that helps them break through a barrier.

It’s resetting their expectations for how all this can get done. It resets our team’s expectations, too.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Listen to my full interviews with Javier and Hillary by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here. (And download any of the past shows here.)

Next on Entrepreneurs are Everywhere : Brandon Bruce, co-founder of Cirrus Insight; and , co-founder of The Root Café.

Tune in Thursday at 1 pm PT, 4 pm ET on Sirius XM Channel 111.

Want to be a guest on the show? Entrepreneurship stretches from Main Street to Silicon Valley, from startups to big companies. Send an email to terri@kandsranch.com describing your entrepreneurial journey.

Filed under: Customer Development, SiriusXM Radio Show

March 22, 2016

Entrepreneurs are Everywhere Show No. 25: Nigel and Vaughn Caldon and Kerry Frank

Tenacity and resilience. Getting people to buy in to your startup vision takes a thick skin, perseverance and willingness to learn. You’ll probably be laughed out of several boardrooms along the way.

Entrepreneurs refuse to take no for an answer.

The latest guests on Entrepreneurs are Everywhere shared what they learned from having their ideas rejected and how those lessons propelled their businesses forward.

The radio show airs on SiriusXM Channel 111 (weekly Thursdays at 1 pm Pacific, 4 pm Eastern). It follows the journeys of founders who share what it takes to build a startup – from restaurants to rocket scientists, to online gifts to online groceries and more. The program examines the DNA of entrepreneurs: what makes them tick, how they came up with their ideas; and explores the habits that make them successful, and the highs and lows that pushed them forward.

Nigel Caldon

Joining me in SiriusXM’s studio in New York were

Nigel and Vaugn Caldon, co-founders of BallStar social network for basketball players

Kerry Frank, founder of Comply365 digital flight bags for commercial aircraft pilots

Vaughn Caldon

Listen to the full interviews with Nigel and Vaughn and with Kerry by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here.

(And download any of the past shows here.)

Kerry Frank

Clips from their interview are below.

Nigel and Vaughn Caldon are brothers who founded the startup The Street Academy for Financial Literacy and now BallStar together. Vaughn served as Associate Director of Alumni Affairs at Prep for Prep. Nigel spent five years working in investment management at Goldman Sachs and Citi Alternative Investments before going in to business with his brother. Nigel also teaches Data Analytics at General Assembly NYC.

In building their companies, the Caldon brothers have found that when things get tough, there’s always a way to make it work.

Nigel : … We’ve done a pretty decent job … bootstrapping with limited resources — trying to figure out different ways to get work done and move the needle without actually spending any money. … There’s always a way and as long as you’re paying attention you’ll always be able to find some sort of resource that’s there to fill exactly what you need done.

Vaughn : You have to love learning… because some of the ‘no’s’ we’ve had have taught us more about the business than, you know, some of the, “Hey, I’d love to be a part of this.”

Steve : Give me an example. Tell me about a ‘no’ that made you smarter.

Vaughn : You know, any ‘no’ from an investor that said, “traction” really meant, ‘I don’t understand your idea, but go ahead and try and prove it to us.’ … also someone who said, “You know, XYZ is this doing better,” or “We use this.” They put us onto a competitor that we didn’t know about. That wasn’t a ‘no’, that was a huge misstep on us not knowing this company was in our space.

Steve : What happens when someone says, “Take a look at this competitor”? What do you do?

Vaughn : You’re in a better position when you know what it is because you don’t have anything and they’re stuck with what they have. That’s really inspiring me to go after what’s already out there.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Kerry Frank co-founded Comply365 in 2007 with her husband. The company has transformed the aviation industry by replacing pilot flight bags with tons of manuals with digital tablets in cockpits.

She struggled early on trying to get customers to see her vision for maintaining aviation manuals and other records on the cloud rather than on paper:

Kerry : Just a couple short months after that final testing (of Comply’s 365 product using a Kindle) the iPad came out and I looked at that. so I said, “Geez, I got to go with the iPad because look at this dynamic color and all of this.” I started running around to all the airlines with either a Kindle or an iPad and saying, “We’re going to change your business, we’re going to revolutionize the way you work, we’re going to take all the paper off the plane, we’re going to save you this much money.” I was laughed out of every boardroom.

… They said, “You’re way too innovative, we’re too risk adverse, we’ll never do this, you’re crazy, come back in a decade.”

… I just continued to say, “No, you don’t have to be a legacy. You don’t have to have that “you can’t change” mentality; you guys can change. Anybody can change. You just have to believe it and we can revolutionize aviation. We can change the way we work and this will be safer. It will be the best for aviation in the long term.” I even went to top charting vendors in the world and said if you do electronic charting …

Steve: Like Jeppesen?

Kerry: Yeah, laughed out of their boardroom. They said, “We’ll never do an iPad.”

Steve: Are they on the iPad now?

Kerry: Yes they are. After a year of persevering, it was tough. We’re living on 50 bucks a week, a family of five (with the business) in the basement of our home. We have some employees, and we never missed payroll and we’re trying to change the world right? We’re trying to change industry. We got our first win and then our second win, and then within 16 months I had pretty much flipped the market.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

—

Focusing on your vision is critical, Vaughn Caldon said:

There’s so much that you want to do and then there’s what you have to do. I think the biggest learning curve is how to be in focused on that straight line. … because there’s something going on over here that you’d love to be involved and have your name next to it … may not be as important as another hour kind of vetting the design with someone you’ve been through it with a hundred times already.

It’s just really about focusing on what’s clearly the next step in front of you. That’s been the biggest lesson for us because … we were quick to bounce around.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Being domain experts and having done one startup together gave the Caldon brothers confidence about starting Ballstar:

Vaughn : The confidence that we can start anything together , came from the fact that we had been the CEO and Director of Development of an organization that we created, and we started interacting on that level. …

The next step (in confidence) was knowing the space. We’re from Brooklyn, we play basketball, we know basketball players. …

… people got on Twitter because Shaquille O’Neal was there first … (Keeping that in mind) we … led with … aspirational leagues.

We went to sign up leagues like West Fourth Street, EVC at the Rucker, Dykeman, Tri-State Classic. These are all iconic leagues that people want to be involved and want to be affiliated with, so getting them on the platform first and catering to them, building that as our customer, and developing those customers was our focus. We knew we could do that.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Here’s how they knew their idea could be a business

Nigel : It obviously started out as an absolute passion (for us).

We had to back-end our way into, figuring out, where is the business (model) in that? You could sell ads or you could sell the data. What we really found that our client was essentially the basketball league, and we could throw ourselves in the middle of the transaction.

There’s almost $2 billion spent in North America on paying to play basketball. If I’m providing a platform-as-a-service to amateur basketball leagues all over the world, now I have the opportunity to take a transaction commission the way Uber does. You can download Uber for free, but as soon as you hail a cab, you’re paying. Download BallStar for free, as soon as you want to play basketball, leave us some change.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

—

Customer discovery paid off for Kerry

Kerry : I listened and it was magic. Everyone started raising their hand and saying, “I have this problem, I have that problem.”

Steve : Did you know you were doing customer discovery?

Kerry : I did. That was a key to my consulting business. … The beautiful thing is when you ask the customers, they’re in the space, they understand it, and they also then have buy in, right, because you’re going to solve their problem …

Steve : For our listeners, this is a brilliant insight. It sounds like you practiced it perfectly. They essentially taught you what the product should do.

Kerry : Right. I have 13 products today and everybody says, “How did you think of those?” I say, “I never thought of those, I was just a really good listener.”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Being self-taught, she said, gave her an edge:

I didn’t go to college. I just started working for people … in all kinds of different jobs. …. I was always really good at whatever I did, because I loved working so much, it was my passion. I’d always start getting promoted to another level, but I have this inner thing inside of me that I can’t describe, that as soon as I started to get promoted to management levels I would quit.

I would say, “No, I have a destiny to do something else, and I’m trying to find my way.” I always also struggled with this part that had to get back into help. I was always then also giving to charities, or working for charities, or working for churches, or youth groups. It was kind of this back and forth. It was this incredible path that people look back on and say that’s crazy.

At the same time it gave me key foundational things that I look on today as a CEO I needed. … (Things) like accounting. I was a bookkeeper, and I managed properties for a long time. It taught me all the accounting principles. It taught me how to handle some of the basic general ledger things.

If you look at different steps in my path, and I’m like, “Wow, that was great,” because now as a CEO I know all these different tools that I needed. Traditionally, you might get that in college, but I didn’t go the college route, so there’s a lot of skills that I picked up along the way that enabled me to be who I am today as a CEO.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Here’s the biggest thing Kerry’s learned from doing a startup:

Kerry : If you have passion and if you’re dedicated to this. It doesn’t matter who you are, where you came from, or what your education is. You can do anything. Everything is possible.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Listen to my full interviews with Nigel and Vaughn and with Kerry by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here. (And download any of the past shows here.)

Next on Entrepreneurs are Everywhere : Javier Saade , former associate administrator for the U.S. Small Business Administration , and Hillary Hartley , deputy executive director of 18F.

Tune in Thursday at 1 pm PT, 4 pm ET on Sirius XM Channel 111.

Want to be a guest on the show? Entrepreneurship stretches from Main Street to Silicon Valley, from startups to big companies. Send an email to terri@kandsranch.com describing your entrepreneurial journey.

Filed under: Customer Development, SiriusXM Radio Show

March 16, 2016

What Founders Need to Know: You Were Funded for a Liquidity Event – Start Looking

There are many reasons to found a startup.

There are many reasons to work at a startup.

But there’s only one reason your company got funded. Liquidity.

——-

The Good News

To most founders a startup is not a job, but a calling.

But startups require money upfront for product development and later to scale. Traditional lenders (banks) think that startups are too risky for a traditional bank loan. Luckily in the last quarter of the 20th century a new source of money called risk capital emerged. Risk capital takes equity (stock ownership) in your company instead of debt (loans) in exchange for cash.

Founders can now access the largest pool of risk capital that ever existed –in the form of Private Equity (Angel Investors, family offices, Venture Capitalists (VC’s) and Hedge Funds.)

At its core Venture Capital is nothing more than a small portion of the Private Equity financial asset class. But for the last 40 years, it has provided the financial fuel for a revolution in Life Sciences and Information Technology and has helped to change the world.

The Bad News

While startups are driven by their founder’s passion for creating something new, startup investors have a much different agenda – a return on their investment. And not just any returns, VC’s expect large returns. VC’s raise money from their investors (limited partners like pension funds) and then spread their risk by investing in a number of startups (called a portfolio). In exchange for the limited partners tying up capital for long periods by in investing in VCs (who are investing in risky startups,) the VCs promise the limited partners large returns that are unavailable from most every other form of investment.

Some quick VC math: If a VC invests in ten early stage startups, on average, five will fail, three will return capital, and one or two will be “winners” and make most of the money for the VC fund. A minimum ‘respectable’ return for a VC fund is 20% per year, so a ten-year VC fund needs to return six times (6x) their investment. This means that those two winner investments have to make a 30x return to provide the venture capital fund a 20% compound return – and that’s just to generate a minimum respectable return.

(BTW, Angel investors do not have limited partners, and often invest for reasons other than just for financial gain (e.g., helping pioneers succeed) and so the returns they’re looking for may be lower.)

The Deal With the Devil

What does this mean for startup founders? If you’re a founder, you need to be able to go up to a whiteboard and diagram out how your investors will make money in your startup.

While you might be interested in building a company that changes the world, regardless of how long it takes, your investors are interested in funding a company that changes the world so they can have a liquidity event within the life of their fund ~7-10 years. (A liquidity event means that the equity (the stock) you sold your investor can now be converted into cash.) This happens when you either sell your company (M&A) or go public (an IPO.) Currently M&A is the most likely path for a startup to achieve liquidity.

Know the End from the Beginning

Here’s the thing most founders miss. You’ve been funded to get to a liquidity event. Period. Your VCs know this, and you need to know this too.

Why don’t VCs tell founders this fact? For the first few years, your VCs want you to keep your head down, build the product, find product/market fit and ship to get to some inflection point (revenue, users, etc.). As the company goes from searching for a business model to growth, only then will they bring in a new “professional” management team to scale the company (along with a business development executive to search for an acquirer) or prepare for an IPO.

The problem is that this “don’t worry your little head” strategy may have made sense when founders were just technologists and the strategy and tactics of liquidity and exits were closely held, but this a pretty dumb approach in the 21st century. As a founder you are more than capable of adding value to the search for the liquidity event.

Therefore, founders, you need to be planning your exit the day you get funded. Not for some short-time “lets flip the company” strategy but an eye for who, how and when you can make an acquisition happen.

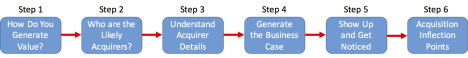

Step 1: Figure out how your startup generates value

For example, in your industry do companies build value the old fashion way by generating revenue? (Square, Uber, Palantir, Fitbit, etc.) If so, how is the revenue measured? (Bookings, recurring revenue, lifetime value?) Is your value to an acquirer going to measured as a multiple of your revenues? Or as with consumer deals, is the value is ascribed by the market?

Or do you build value by acquiring users and figuring out how to make money later (WhatsApp, Twitter, etc.) Is your value to an acquirer measured by the number of users? If so, how are the users measured (active users, month-on-month growth, churn)?

Or is your value going to be measured by some known inflection point? First-in-human proof of efficacy? Successful Clinical trials? FDA approvals? CMS Reimbursement?

If you’re using the business model canvas, you’ve already figured this out when you articulated your revenue streams and noted where they are coming from.

Confirm that your view of how you’ll create value is shared by your investors and your board.

Step 2: Figure out who are the likely acquirers

If you are building autonomous driving aftermarket devices for cars, it’s not a surprise that you can make a short list of potential acquirers – auto companies and their tier 1 suppliers. If you’re building enterprise software, the list may be larger. If you’re building medical devices the list may be much smaller. But every startup can take a good first cut at a list. (It’s helpful to also diagram out the acquirers in a Petal Diagram.)  When you do, start a spreadsheet and list the companies. (As you get to know your industry and ecosystem, the list will change.)

When you do, start a spreadsheet and list the companies. (As you get to know your industry and ecosystem, the list will change.)

It’s likely that your investors also have insights and opinions. Check in with them as well.

Step 3: List the names of the business development, technology scouts and other people involved in acquisitions and note their names next to the name of the target company.

All large companies employ people whose job it is to spot and track new technology and innovation and follow its progress. The odds on day-one are that you can’t name anyone. How will you figure this out? Congratulations, welcome to Customer Discovery.

Treat potential acquirers like a customer segment. Talk to them. They’re happy to tell anyone who will listen what they are looking for and what they need to see by way of data or otherwise for something to rise to the level of seriousness on the scale of acquisition possibilities.

Understand who the Key Opinion Leaders in your industry are and specifically who acquirers assemble to advise them on technology and innovation in their areas of interest.

Get out of the building and talk to other startup CEOs who were acquired in your industry. How did it happen? Who were the players?

It’s common for your investors to have personal contacts with business development and technology scouts from specific companies. Unfortunately, it’s the rare VC who has already built an acquisition roadmap. You’re going to build one for them.

After awhile, you ought to be able to go to the whiteboard and diagram the acquisition decision process much like a sales process. Draw the canonical model and then draw the actual process (with names and titles) for the top three likely acquirers

Step 4: Generate the business case for the potential acquirer

Your job is to generate the business case for the potential acquirer, that is, to demonstrate with data produced from testing pivotal hypotheses why they need is what you have to improve their business model (filling a product void; extending an existing line; opening a new market; blocking a competitor’s ability to compete effectively, etc.)

Step 5: Show up a lot and get noticed

Figure out what conferences and shows these acquirers attend. Understand what is it they read. Show up and be visible – as speakers on panels, accidently running into them, getting introduced, etc. Get your company talked about in the blogs and newsletters they read. How do you know any of this? Again, this is basic Customer Discovery. Take a few out to lunch. Ask questions – what do they read? – how do they notice new startups? – who tells them the type of companies to look for? etc.

Step 6: Know the inflection points for an acquisition in your market

Timing is everything. Do you wait 7 years until you’ve built enough revenue for a billion-dollar sale? Is the market for Machine Learning startups so hot that you can sell the company for hundreds of millions of dollars without shipping a product?

For example, in Medical Devices the likely outcome is an acquisition way before you ship a product. Med-tech entrepreneurship has evolved to the point where each VC funding round signals that the company has completed a milestone – and each of these milestones represents an opportunity for an acquisition. For example, after a VC Series B-Round, an opportunity for an acquisition occurs when you’ve created a working product and you have started clinical trials and are working on getting a European CE Mark to get approval.

When to sell or go public is a real balancing act with your board. Some investor board members may want liquidity early to make the numbers look good for their fund, especially if it is a smaller fund or if you are at a later point in their fund life. If you’re on the right trajectory, other investors, such as larger funds or where you are early in their fund life, may be are happy to wait years for the 30x or greater return. You need to have a finger on the pulse of your VCs and the market, and to align interests and expectations to the greatest extent possible.

You also need to know whether you have any control over when a liquidity event occurs and who has to agree on it. (Check to see what rights your investors have in their investment documents.) Typically, a VC can force a sale, or even block one. Make sure your interests are aligned with your investors.

As part of the deal you signed with your investors was a term specifying the Liquidation Preference. The liquidation preference determines how the pie is split between you and your investors when there is a liquidity event. You may just be along for the ride.

Above all, don’t panic or demoralize your employees

The first rule of Fight Club is: you do not talk about Fight Club. The second rule of Fight Club is: you DO NOT talk about Fight Club! The same is true about liquidity. It’s detrimental to tell your employees who have bought into the vision, mission and excitement of a startup to know that it’s for sale the day you start it. The party line is “We’re building a company for long-term success.”

Do not obsess over liquidity

As a founder there’s plenty on your plate – finding product/market fit, shipping product, getting customers… liquidity is not your top of the list. Treat this as a background process. But thinking about it strategically will effect how you plan marketing communications, conferences, blogs and your travel.

Remember, your goal is to create extraordinary products and services – and in exchange there’s a pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.

Lessons Learned

The minute you take money from someone their business model now becomes yours

Your investors funded you for a liquidity event

You need to know what “multiple” an investor will allow you to sell the company for

Great entrepreneurs shoot for 20X

You need at least a 5x return to generate rewards for investors and employee stock options

A 2X return may wipe out the value of the employee stock options and founder shares

You can plan for liquidity from day one

Don’t demoralize your employees

Don’t obsess over liquidity, treat it strategically

Filed under: Technology, Venture Capital

March 11, 2016

Learning Through Reflection

“Sometimes, you have to look back in order to understand the things that lie ahead.”

We just finished the 6th annual Lean LaunchPad class. This year we made a small but substantive addition to way we teach the class, adding a week for reflection. The results have made the class massively better.

For the last 6 years I’ve taught the Lean LaunchPad class at Stanford and Berkeley. To be honest I built the class out of frustration watching schools teach aspiring entrepreneurs that all they need to know is how to write a business plan or how to sit in an incubator building a product.

If you’ve read any of my previous posts, you know I believe that:

a product is just a part of a startup, but understanding customers, channel, pricing, – the business model – is what turns a product into a business

business plans are fine for large companies where there is an existing market, existing product and existing customers, but they are useless in a startup where most often none of these are known

entrepreneurship is experiential and requires theory and a ton of practice.

Therefore, we developed the 8-week Lean LaunchPad class to teach students how to think about all the parts of building a business, not just the product. We organized the class as:

Team-based

Students apply and learn as teams of 4. Eight teams per class

A “flipped” classroom

Students watch the lectures as homework via our MOOC

Every week we teach a new part of the theory of how to commercialize an insight or invention

using the business model canvas as the framework

Every week we teach the practice of Lean

by having the students get out of the classroom and talk to 10-15 customers a week and build a new Minimum Viable Product weekly

in order to validate/invalidate their business model hypotheses

The teaching team critiques their progress and suggests what they might do next

Every week the teams present their results

“Here’s what we thought, here’s what we did, here’s what we found, here’s what we are going to do next”

The combination of the Business Model Canvas, Customer Development and Agile Engineering is an extremely efficient template for the students to follow. It drives a hyper-accelerated learning process which leads the students to a “information dense, evidence-based” set of conclusions. (Translation: they learn a lot more, in a shorter period of time, than in any other entrepreneurship course we’ve taught or seen.)

The combination of the Business Model Canvas, Customer Development and Agile Engineering is an extremely efficient template for the students to follow. It drives a hyper-accelerated learning process which leads the students to a “information dense, evidence-based” set of conclusions. (Translation: they learn a lot more, in a shorter period of time, than in any other entrepreneurship course we’ve taught or seen.)

Demo Days Versus Lesson Learned Presentations

One thing we always kept in mind – we were teaching students a methodology and a set of skills for the rest of their lives – not running an incubator or accelerator. As a consequence, we couldn’t care less about a “Demo Day” at the end of the class. We don’t want our students focused on fund-raising, we want them to maximize their learning. Secondly, even for fund-raising, you couldn’t invent a less useful format to evaluate a startup’s potential then the Demo Days held by accelerators. Demo Days historically have been exactly what they sound like, “Show me how smart your team is at this instant in time.” Everything depends on a demo, presentation and speaking style.

We designed our class to do something different. We wanted the teams to tell the story of their journey, sharing with us their “Lessons Learned from our Customers”. They needed to show what they learned and how they learned it after speaking to 100+customers, using the language of class: interview, iterations, pivots, restarts, experiments, minimal viable products, evidence. The focus of their presentations is on how they gathered evidence and how it impacted the understanding of their business models – while they were building their MVP.

Reflection Week

In the past, our teams would call on customers until the last week of the class and then present their Lessons Learned. The good news is that their presentations were dramatically better than those given at demo days – they showed us what they learned over 8 weeks which gave us a clear picture of the velocity and trajectory of the teams. The bad news is since their heads were down working on customer discovery until the very end, they had no time to reflect on the experience.

We realized that we had been so focused in packing content and work into the class, we failed to give the students time to step back and think about what they actually learned.

So this year we made a change. We turned the next to last week of the class into a reflection week. Our goal—to have the students extract the insights and meaning from the work they had done in the previous seven weeks.

We asked each team to prepare a draft Lessons Learned presentation telling us about their journey and showing us their:

Initial hypotheses and Petal diagram

Quotes from customers that illustrated learnings and insights

Diagrams of key parts of the Canvas –customer flow, channel, get/keep/grow (before and after)

Pivot stories

Screen shots of the evolution of Minimum Viable Product (MVP)

Demo of final MVP

The teaching team reviewed the drafts and provided feedback to the teams and to the class as a whole. We discussed what general patterns and principles they extracted from all the customer interaction they had. On the last day of class, each team shared their Lessons Learned presentations, giving everyone in the class the benefit of what every team has learned.

We used this week to help teams reflect that they accomplished more than they first realized. For the teams who found that their ideas weren’t a scalable business, we let them conclude that while it was great to celebrate the wins, they could also embrace and celebrate their failures as low cost learning.

By the time the final week of the final Lessons Learned presentations rolled around, the students were noticeably more relaxed and happier than teams in past classes. It was clear they had a solid understanding of the magnitude of their journey and the size of their accomplishments – eight teams had spoken to nearly 900 customers, built 50 minimum viable products, and tested tons of hypotheses.

Here are four examples from our 2016 Stanford class

Pair Eyeware

Be sure to look at how they tested their hypotheses on slides 11 and 12, and the before and after value proposition canvases on slide 13 -17. A great competitive Petal diagram is on slide 22

Share and Tell

Great story and setup in slides 3-7. Understanding their market in week 6, slide 31.

Allocate

Notice how they learned about their customer archetypes on slides 12-14. After 80 interviews, a big pivot on slide 16.

Nova Credit

Look at the key hypotheses on slide 2 and their journey in the class on slide 5.

Lessons Learned

Dedicating a week for reflections expands what everyone learns

Students extract the insights and meaning from the work they did

See all the presentations here

Filed under: Lean LaunchPad, Teaching

March 9, 2016

Entrepreneurs are Everywhere Show No. 24: Drew Silverstein and Craig Kanarick

“This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact…print the legend”

The Hollywoodization of Silicon Valley startup stories “prints legends,” but for most startups those stories are pure fiction. They don’t tell the awful, painful, and exhausting job it is to build a business.

The two guests on today’s Entrepreneurs are Everywhere radio show tell it like it really is to navigate the chaos of a startup.

The show follows the journeys of founders who share what it takes to build a startup – from restaurants to rocket scientists, to online gifts to online groceries and more. The program examines the DNA of entrepreneurs: what makes them tick, how they came up with their ideas; and explores the habits that make them successful, and the highs and lows that pushed them forward.

Drew Silverstein

Joining me in SiriusXM’s studio in New York were:

Drew Silverstein, co-founder and CEO of the music technology venture Amper Music

Craig Kanarick, founder of the indie food site Mouth

Craig Kanarick

Listen to the full interviews with Drew and Craig by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here.

(And download any of the past shows here.)

Clips from their interview are below.

Drew Silverstein is an award-winning composer, producer, and conductor for film, television, records, video games, and an MBA student at Columbia Business School.

He created Amper Music to change the way music is composed and created for video content, but it is not his first startup.

At his first venture, Henry O’Bryan, LLC, Drew quickly learned that startup life is nothing like the movies.

Drew : It wasn’t a successful startup. We didn’t sell it. We didn’t IPO it. It went really well for a while … and then we closed it down breaking about even. I think that removed the sheen of startup glory (for me).

… I had the perception of, “You start a company, you build it, you go, and ta-da!”

Steve : It grows up like Facebook.

Drew : Exactly. … Just like the movies. I should’ve known (that wasn’t true) because I’m in Hollywood, and we know what really happens behind the scenes. …

… In a startup you need to be an expert in what you’re doing – not just doing something you have a cool idea for. You better know the problem in and out, and if you can have lived it, even better.

It’s important to have a fantastic team around you. We had a great team, but I wasn’t the best, most valuable team member I could’ve been for the project.

… I learned that in a startup things don’t always go well. In fact, usually they’re not going well.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Craig Kanarick’s career has integrated digital technology, design and strategy. In 1995, he co-founded the digital services firm, Razorfish and grew it from a two-man startup to more than $250 million and 2,200 employees. Craig also co-founded Razorfish Studios, a media and entertainment company, producing books, films, TV shows, albums and websites.

After leaving Razorfish in 2001, Craig spent a year immersed in food, including a stint as a prep cook at Babbo, Mario Batali’s flagship restaurant. At the Rockwell Group, the architecture and design firm, he co-founded Studio Red and the Lab, an incubator for integrating digital technology into physical spaces. He founded Mouth in 2012.

At Razorfish, Craig’s lack of startup experience showed:

We expanded too quickly, and in particular we merged with a company that was a complete culture clash with the rest of the company. We were creative designers and front-end developers in a highly creative environment, and we merged with a Boston-based back-end technology company who was working in Fortran, and old school.

(In hindsight, the culture) mattered a huge amount. After the merger people were asking, “Why am I working for these people now? I don’t get them. I don’t understand them. I don’t like this place … “

… The other (mistake) was … not responding to the market and understanding how the market was changing and how quickly it was changing.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Founders, he acknowledges, sometimes get past their skill set

…there’s a big difference between creating things, managing things, and operating things. We were better at creating things and not so good at managing or operating them.

… I’d not even managed myself. I’d never been a boss of anybody before Razorfish … so we really had to learn everything on the fly.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

—

Drew shared where the idea for Amper came from:

We recognized that what we were doing in terms of writing music … could be distilled.

Not distilling the high artistic level but at its core we could distill what we were doing into a process that could be replicated by a computer.

… Algorithmic computer music has been around for decades but we think we’ve figured out a novel way to approach the solution based on our experiences as film composers.

At the same time we had clients coming to us and saying, “We need this. Not every project we do is this high-budget triple A blockbuster. With these other projects, we don’t like the (music) solution that we have. Can you do it for us instead?”

We … put one and one together and said, “If we can offer you a solution that provides the product that you want, the music that you want, that’s driven algorithmically, is this something that you’d be interested in?”

Overwhelmingly the response was like, “Yes. Yes. Can we have it yesterday. Why don’t you have it already?”

And that’s … when we said, “All right. We don’t know if we can do it but it sounds like we should explore the opportunity.”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Customer input shaped Amper’s product:

One of the things that was really important to us was using Lean methodology. We … ended up doing it before we knew what Lean was…

… Before we had a clue what that was, (we had customer input). … We said at its core, what are our assumptions, how do we validate them, and then how do we change paths or iterate based on that as quickly as possible?

… outside the building, you learn how many nuances there are to what you’re doing. It’s not one big umbrella of a problem; there are so many different elements to it. … We learned it’s not just music for media it’s, well, here’s one use case, here’s another use case, who is doing it and why? You you need to boil this down to the most pinpoint thing you’re going to do, be successful at that, and then grow.

I think unless you’re asking people and learning from people and asking to meet more people and figuring out where this is going … it will take a lot more time to figure that thing out than doing it the lean way.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Drew wishes there was a playbook for how to be a startup CEO at Amper:

There is a lot of information on, “How do you raise money?” (but) there’s a lack of information, or certainly less thereof, in terms of what do you do after you raise money? How do you run a business and how do you be the person you need to be to everyone you’re interacting with? How do you deal well with investors, with customers, with employees, with your colleagues?

… you are responsible now. People have given you a lot of money and said, “Do this thing.” …fortunately, we have a great team of advisors, who I think are invaluable because, just like anything, it’s an apprenticeship.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

—

Craig explained how fund-raising has changed since doing his first startup:

It’s completely different. … There was no angel investing in the days of Razorfish. It was all strategic partnerships leading to IPOs. That’s just not the path right now. The whole idea of crowdsourcing and crowd-funding and doing angel investing, and then a series A with VCs, that path didn’t exist in the late ’90s at all.

(Today) there’s more access to capital, and it’s a pro-entrepreneur world. It’s cool to be an entrepreneur.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Here’s why Craig started up again:

The first thing that I tell people is to make sure that you love what you’re doing, because you’re going to have to work an enormous number of hours doing it.

You’re going to spend a huge percentage of your time doing this, you’ve got to love what you do, you have to be good at it, and you have to be honest about both of those two things.

Because you can fool yourself into thinking it’s worth it because I’m going to get paid at the end. When the Internet was on fire people said, “How do I make some money off this Internet thing?” If you’re asking that question, you’re in the wrong place.

Steve : You know my line is, “Entrepreneurship, it’s not a job, it’s a calling. It’s the world worst job, but it’s the world’s best calling.”

Craig : It is. It’s the reason I’m doing it again.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Listen to my full interviews with Drew and Craig by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here. (And download any of the past shows here.)

Next on Entrepreneurs are Everywhere: Nigel and Vaugn Caldon, co-founders of BallStar and Kerry Frank, founder of Comply365.

Tune in Thursday at 1 pm PT, 4 pm ET on Sirius XM Channel 111.

Want to be a guest on the show? Entrepreneurship stretches from Main Street to Silicon Valley, from startups to big companies. Send an email to terri@kandsranch.com describing your entrepreneurial journey.

Filed under: Customer Development, SiriusXM Radio Show

March 1, 2016

Entrepreneurs are Everywhere Show No. 23: Nina Tandon and Brandon McNaughton

In a startup cheap may be expensive.

And just having cool technology doesn’t make a successful business.

What it was like to get out of the research lab to build a startup was the focus of interviews with two of the latest guests on Entrepreneurs are Everywhere, my radio show on SiriusXM Channel 111 (airing weekly Thursdays at 1 pm Pacific, 4 pm Eastern).

The show follows the journeys of founders who share what it takes to build a startup – from restaurants to rocket scientists, to online gifts to online groceries and more. The program examines the DNA of entrepreneurs: what makes them tick, how they came up with their ideas; and explores the habits that make them successful, and the highs and lows that pushed them forward.

Nina Tandon

Joining me in SiriusXM’s studio in New York were:

Nina Tandon, CEO and co-founder of EpiBone, the world’s first company growing bones for skeletal reconstruction

Brandon McNaughton, co-founder and CEO of Akadeum Life Sciences cell sorting technology company

Brandon McNaughton

Listen to the full interviews with Nina and Brandon by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here.

(And download any of the past shows here.)

Clips from their interview are below

In addition to her work with EpiBone, Nina Tandon is the co-author of Super Cells: Building with Biology . She is an Adjunct Professor of Electrical Engineering at the Cooper Union. Nina has a bachelor’s in Electrical Engineering from the Cooper Union, a master’s in Bioelectrical Engineering from MIT, a PhD in Biomedical Engineering, and an MBA from Columbia University. Her PhD research studied electrical signaling in cardiac, skin, bone, and neural tissue. Fast Company named Nina one of the 100 Most Creative People in Business .

While building EpiBone, she quickly learned to avoid business shortcuts:

Nina : Cheap is expensive.

Steve : What does that mean?

Nina : I don’t think there’s any corners that can be cut. Sometimes if someone offers you free services …, it can be tempting to take them up on that offer, but then you might create a problem that’s a lot more expensive to unwind down the road.

Steve : Because you’re committed to the wrong people, the wrong service or whatever?

Nina : (Nods.) I’ve made some mistakes that are inadvertent but that needed to be undone.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

A tech entrepreneur and inventor, Brandon McNaughton was entrepreneur in residence for Detroit Innovate , an early-stage venture fund . He also founded and served as chief technology officer of Life Magnetics. Brandon teaches entrepreneurship at the University of Michigan Center for Entrepreneurship.

Brandon’s current startup Akadeum was one of the 760 teams to go through the National Science Foundation (NSF) Innovation Corps, which teaches scientists and engineers how to take their science out of the lab and into the marketplace.

Brandon’s biggest takeaway from the NSF program had nothing to do with technology:

I’ve learned that business is about relationships. Relationships with customers, it’s relationships with your employees, your investors, because when you buy something, there’s an expectation, there’s a back and forth.

That’s something that I didn’t really appreciate until after my first startup. I thought it was all about the technology, “Oh, if I could just get this technology to work. If I could just get it to do this, then everything’s going to be OK,” and in some ways I now think technology doesn’t matter. … what matters more is the … the customer’s problem.

… I think the epiphany was when we closed down Life Magnetics …It was hard to find that right product-market fit. The technology was working, but finding that market fit was challenging. …

…We couldn’t figure out the right business model to move forward with. That’s actually how I look at startups now. It’s trying to find that business model as quickly as you can that will support a company. You don’t need new gee-whiz technology to do that. What you need is to understand the problem to know what do deliver to the customer.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Getting to know customers, Brandon said, only happens if you get out of the lab and talk to them:

Brandon : (The I-Corps program) was a combination of being an accelerant, but also getting us (the founders) on the same page, because we all had … different mental images and … different expectations …

Steve : Of what a customer was and what commercialization was?

Brandon : (Nods.) And whether or not we wanted to start a company, when we were going to start a company, and what the company would look like.

The I-Corps process was great. It was exciting to see Gwangseong Kim, (my grad student and member of the Akadeum founding team) up in front of the class because as the entrepreneurial lead he was the one who got up there and presented what we learned. (co-founder) John Younger and I just stood there … I mean, we also did the work, too, talking to customers, things like that. But the entrepreneurial lead is the one who gets to represent the team.

… It was so amazing to watch the transformation in him. And for Gwangseong one great moment was (when) he did his first cold (customer) call. When we were in Berkeley, we were talking about cold calling and how to do it. (And Gwangseong) was a little bit of apprehension…

Steve : Because he’s a scientist?

Brandon : Exactly. I still have that even when I talk to certain people, it’s like, “Oh, I’m bothering somebody …”

(But) Gwangseong made the call and within 15 minutes he gets invited to lunch the next day. Right? So he hit a nerve with a potential customer and was incredibly excited that you could make a call and get that kind of response.

…this (lunch meeting) was the kind of thing you dream about (when you’re starting a company). You want to find those moments of opportunity and you don’t know unless you make the call, you don’t know unless you go.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

—

Nina shared what it was like to get out of comfort zone of the lab: