Steve Blank's Blog, page 31

August 25, 2015

Why Corporate Entrepreneurs are Extraordinary – the Rebel Alliance

I’ve spent this year working with corporations and government agencies that are adopting and adapting Lean Methodologies. The biggest surprise for me was getting schooled on how extremely difficult it is to be an innovator inside a company of executors.

—–

What Have We Lost?

I’ve been working with Richard, a mid-level executive in a large federal agency facing increasing external disruption (technology shifts, new competitors, asymmetric warfare, etc.). Several pockets of innovation in his agency have begun to look to startups and have tried to adopt lean methods. Richard has been trying to get his organization to recognize that change needs to happen. Relentless and effective, Richard exudes enthusiasm and radiates optimism. He’s attracted a following, and he had just been tapped to lead innovation in his division.

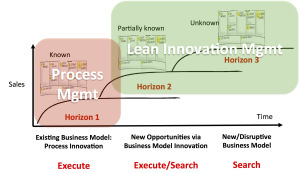

He’s working to get his agency to adopt Lean and the Horizon 1, 2, and 3 innovation language (Horizon 1 executes current business models, Horizon 2 extends current business models and Horizon 3 searches for new business models) and was now building a Lean innovation pipeline created out of my I-Corps/Lean LaunchPad classes.

Yet today at dinner his frustration just spilled out.

“Most of the time our attempts at innovation result in “innovation theater” – lots of motion (memos from our CEO, posters in the cafeteria, corporate incubators) but no real change. We were once a scrappy, agile and feared organization with a “can-do” attitude. Now most people here don’t want to rock the boat and simply want do their job 9 to 5. Mid-level bureaucrats kill everything by studying it to death or saying it’s too risky. Everything innovative I’ve accomplished has taken years of political battles, calling in favors, and building alliances.” He thought for a minute and said, “Boy, I wish I had a manual to tell me the best way to make this place better.”

Richard continued, “Innovation is something startups do as part of their daily activities – it’s in their DNA. Why is that?”

While I understood conceptually that adopting new ideas was harder in larger companies, hearing it first-hand from a successful change agent made me realize both how extraordinary Richard was and how extraordinarily difficult it is to bring change to large organizations. His two questions– 1) Was there a manual on “how to be a successful corporate rebel”? and 2) Why are startups innovative by design but companies are innovative by exception?–left me searching for answers.

Why Startups are Innovative by Design

If you come from the startup world, you take for granted that on day one startups are filled with rebels. Everyone around you is focused on a single goal – disrupt incumbents and deliver something innovative to the market.

In a (well-run) startup, the founder has a vision (at first a series of untested hypotheses) and rallies employees and investors around that singular idea. The founders get out of building and rapidly turn the hypotheses into facts by developing a series of incremental and iterative minimal viable products they test in front of customers in search of product-market fit.

While there might be arguments internally about technology and the right markets, no one is confused about the company’s goal – find a sustainable business model, get enough revenue, users, etc., before you run out of money.

Every obstacle Richard described in his agency simply does not exist in the early days of a startup. Zero. Nada. For the first year or so startups actually accumulate technical and organizational debt as they take people and process shortcuts to just get the first orders, 100,000 users or whatever they need to build the business. All that matters is survival. Process, procedures, KPI’s, org charts, forms, and bureaucracy are impediments to survival as a new company struggles to search for and find a repeatable business model. Founding CEO’s hate process, and actually beat it out of an organization when it appears too early.

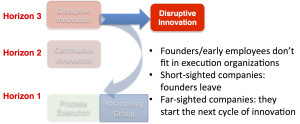

In the technology world companies that grow large take one of two paths. Most common is when startups do find a repeatable and scalable business model they hire people to execute the successful business model. And these hires turn the startup into a company – a Horizon 1 or 2 execution organization focused on executing and extending the current business model – with the leadership incented for repeatability and scale. (See here for explanations of the three Horizons of Innovation.)

But often as the company/agency scales, the early innovators feel disfranchised and leave. Subsequently, when a technology and/or platform shift occurs, the company becomes a victim of disruption and unable to innovate, usually stagnates and dies.

Alternatively, a company/agency scales but continues to be run by innovators. The large companies that survive rapid technology and/or platform shifts are often run by founders, (Jeff Bezos at Amazon, Steve Jobs at Apple, Larry Page at Google, Larry Ellison at Oracle) or faced with an existential crisis and forced to change (Satya Nadella at Microsoft) or somehow have miraculously retained an innovation culture through multiple generations of leadership like W.L. Gore.

I offered that perhaps his top-level management would embrace Three Horizons of Innovation from the top-down. Richard replied, “In a perfect world that would be great, but in most agencies (and companies) the CEO or board is not a visionary. Even when our CEO’s acknowledged the need for Horizon 3 innovation, the problem isn’t solved because entrepreneurs run into either “a culture of no” or worse yet the intransigent middle management.

Richard explained, “In a Horizon 1-dominated culture, where everyone is focused on Horizon 1 execution, you can’t grow enough Horizon 3 managers. Instead we’ve found that support for innovation has to come from rare leaders embedded in the Horizon 1 organizations who “get it.” We’ve always had to hide/couch Horizon 3 style change in Horizon 1 and Horizon 2 language, which is maddening but I do what works. In Silicon Valley, the operative word in any pitch is “disrupt.” In Horizon 1 organizations, uttering the word “disrupt” is the death of an idea.”

That really brought home the stark difference between our two worlds.

(Lean Innovation management now offers Horizon 1 executives a set of tools that allow them to feel comfortable with Horizon 2/3 initiatives. Investment Readiness Levels are the Key Performance Indicators for Horizon 1 execs to measure progress.)

What about a manual of “how to be a successful corporate rebel”? Serendipitously after I gave my Innovation @ 50x presentation, someone gave me a book saying “thanks for the strategy, but here are the tactics.” This book entitled Rebels@Work had some answers to Richard’s question.

Rebels at Work

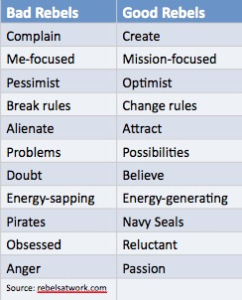

If you’re a mid-level manager in a company or government agency trying to figure out how to get your ideas adopted, you must read Rebels@Work – it will save your sanity.  The book, which was written by successful corporate innovators, offers real practical, tactical advice about how to push corporate innovation.

The book, which was written by successful corporate innovators, offers real practical, tactical advice about how to push corporate innovation.

One of the handy tables explains the difference between being a “bad rebel” versus a “good rebel.” The chapters march you through a series of “how to’s”: how to gain credibility, navigate the organizational landscape, communicate your ideas, manage conflict, deal with fear uncertainty and doubt, etc. It illustrates all of this with real-life vignettes from the authors’ decades-long experience trying to make corporate innovation happen.

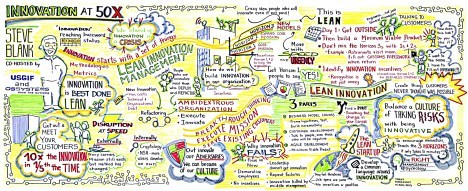

The Innovation at 50x presentation gives corporate rebels the roadmap, common language, and lean tools to develop a Lean innovation strategy, but Rebels@Work gives them the tools to be a positive force for leading change from within.

After I read it I bought 10 copies for Richard and his team.

Lessons Learned

In a startup we are by definition all born as rebels

While startups are not smaller versions of large companies, companies are very much not larger versions of startups

Canonical startup advice fails when applied in large companies

The Three Horizons offer a way to describe innovation strategy across a company/agency

Lean Innovation Management allows startup speed inside of companies

However:

Horizon 1 managers run the company and are not rebels

Horizon 3 ideas might have to be couched in Horizon 1 and 2 language

Rebels@Work offers practical advice on how to move corporate innovation forward

Filed under: Big Companies versus Startups: Durant versus Sloan, Lean LaunchPad

August 21, 2015

Innovation @ 50x in Companies and Government Agencies

I’ve spent this year working with corporations and government agencies trying to adapt and adopt Lean Methodologies. In doing so I’ve learned a ton from lots of people. I’ve summarized my learnings in this blog post, and here and here and here and put it all together in the presentation below.

if you can’t see the presentation click here.

But the biggest surprise for me was getting schooled on how extremely difficult it is to be an innovator inside a company of executors. More on that in the next post.

Filed under: Big Companies versus Startups: Durant versus Sloan, Customer Development, Investment Readiness Level, Lean LaunchPad

July 27, 2015

Part 2 of Episode 6 on Sirius XM Channel 111: Steve Weinstein and Venk Shukla

My guests on Bay Area Ventures on were:

Errol Arkilic, former program director for the National Science Foundation Innovation Corps (NSF I-Corps), now founder of M34 Capital

Steve Weinstein, CEO of MovieLabs

Venk Shukla, president TiE Silicon Valley and general partner, Monta Vista Capital

Part 1 of this post, here, was how Errol Arkilic and the National Science Foundation Innovation Corps changed the way the U.S. government commercializes science.

Part 2, this post is my interview with Steve Weinstein and Venk Shukla. I spoke with Steve about innovation in the movie industry, and to Venk about his journey from bureaucrat in India to entrepreneur here in the U.S., and his work helping other Indian entrepreneurs through TiE, the Indus Entrepreneur network. Both were great interviews worth listening to in their entirety.

—

Steve Weinstein is the CEO and founder of MovieLabs, the research consortium for the six Hollywood major studios.  MovieLabs is researching how to redefine the movie experience, advance content distribution, and understand media consumers. Steve also teaches my Lean LaunchPad course at Berkeley and Stanford, and is the cofounder of Kinetrope, a product design shop working on bringing to market devices in the area of entertainment and IoT.

MovieLabs is researching how to redefine the movie experience, advance content distribution, and understand media consumers. Steve also teaches my Lean LaunchPad course at Berkeley and Stanford, and is the cofounder of Kinetrope, a product design shop working on bringing to market devices in the area of entertainment and IoT.

Previously, Steve was CTO at Deluxe Entertainment, the provider of production, post-production and distribution services to the movie and TV industry; and EVP and Chief Strategy and Technology Officer at Rovi, where he led the media company’s transition from physical technologies to e-commerce, connected home and subscription services. Additionally, Steve has held executive-level positions at Vicinity (a mapping company,) Microprose/Spectrum HoloByte (console and PC game company), Electronics for Imaging (print processing), and Media Cybernetics (image processing). He also was chief architect at Ship Analytics for ship, sub and helicopter trainers. Steve started his career at Naval Research Laboratory in advanced signal processing, computer language design, and real time os development. Steve has been around the block!

Listen to my full interview with Steve here

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Click on the links below to hear Steve discuss

Why movie studios need an R&D lab

“Back in 2005 … (movie studios) were very worried about piracy, and were also worried that the whole digital world was coming on like a freight train and they really didn’t understand it.

Piracy has stabilized (like) the way that theft from ..Wal-Mart – when you walk out the door with a product – but digital (theft) obviously has gone on in ways that we can’t imagine. Also, (the studios wanted to know) how to think about your customer, how you make products for that customer and what the experience should be like. …

(MovieLabs has) created things like UltraViolet, which is a joint studio effort. We’ve done standards, basically an ISBN number for the studios, common ways of thinking about customers, new ways to do production, how tell someone a movie’s available, not available … lots of different things that studios could agree on.”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

3D technology in theaters and at home

“When you think about the theatrical experience, {studios are) trying to make it more important than just giving you a drink holder and a better chair. … Theatrical – going to the movies — has been basically flat in terms of growth. People have other things to do and so 3D was (the studios) first attempt to improve it. And it worked reasonably well on some big tent-pole movies, you know Avengers-style movies, movies that are fantastical, and you can do a new world … action movies.

But it doesn’t work so well in the home because you have to wear glasses. … Everybody (watching at home) now uses three screens. 1) You’re watching your TV while 2) you’re watching your tablet while 3) you’re getting text-messages on your phone. … The number of people doing that is well over 40 percent right now. … and the other problem is that people don’t only watch movies on their TV. They watch it on their iPad and their phone. Mobile is big even for the studios, which brings up a lot of issues. 3D didn’t work out in the home.”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Virtual reality

“For first-person shooter games … and the porn industry – it’s obviously going to be good… All of the studios are experimenting with virtual reality. They do think it’s a tool that might be in their tool chest as an output device.

(However,) if you’ve used Virtual Reality, currently about 20 minutes is your limit because you get disoriented, at least a lot of people do. (It effects some people) the way that some people didn’t like 3D because their eyes… couldn’t see the 3D effect, Virtual Reality has also an effect that way. It’s also isolating. You’re sitting there will a helmet on and you have no other visual stimuli so it’s a little confusing to the brain. … It tracks your head, so when you turn right you see the scene to the right and you turn left you see the scene to the left, up and down. And so it’s great for walk-throughs. Kind of VR effects going on a rollercoaster or jumping out of an airplane, these things look spectacular. … But it’s definitely not for long-term content, like over 10 minutes, 15 minutes. But you’ll see all the studios put out two-minute teasers behind the scenes of Stars Wars or things like that.”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Drones as part of Moviemaking

“If you watch any movies, any of these shots that are aerial, any shots that require flying through a room, or (currently require) trucks driving with (cameras on) hook and ladders or on the top of cherry pickers, now you can set up a commercial drone … and you can do quite a spectacular special effect shot basically for a little money.

Remember, years ago The Sound of Music showed Julie Andrews? That was an incredibly hard shot where they show her up on the mountain with a 360? Now you can do that yourself. … There are drone companies. Everything now in production is a service, so there are drone services. … That will be one of the few thing that are starting to decrease the cost of a movie because you can have effects you couldn’t have before.”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Is Ownership of Movies Dead?

Ownership is in transition. … Ownership of movies for collectors, when it was physical media, meant something. You had something on your shelf. Now ownership is in transition. It’s not so different than watching rentals, so the studios are working on lots of different ideas. Do you give a behind-the-scenes tour if you own the movies? Do you get access to other stuff that makes you live the movie rather than just watch the movie? And I think you’ll see over the next year quite a lot happening in that regard. … Some people are OK with rental, some people are OK with subscription and I think ownership you’ll see in the next year or two start to gain back … if the studios make some things you really want.

Remember a lot of movies are environments. … ComicCon’s going on now, you know people dressing up as people, it used to be a comic trade show, but how it’s a place for popular culture. People live and experience movies, you know Harry Potter franchise, the Fast and Furious franchise, the Star Wars franchise. So people want more, they want to be part of the environment, and I think that’s what you’ll see with ownership.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

—

In the next segment, I spoke with Venk Shukla about his journey from bureaucrat in India to Silicon Valley entrepreneur.

Venk Shukla has worked in numerous early-stage companies as an executive, investor, board member, or advisor.  Currently he’s general partner with Monta Vista Capital, and president of The Indus Entrepreneur (TiE), a 21-year-old global nonprofit that promote wealth creation through entrepreneurship. Venk also started a CIO Forum, which connects 25 CIOs from companies such as Costco, WalMart, Clorox, GE Capital, HCA Health Care and others with the most innovative B2B companies in the Valley. In addition, he is the founding chair and active member of TiE Angels, one of the most active Angel investor groups in the Valley with 140 members and 26 investments in the last three years, mostly in the B2B space.

Currently he’s general partner with Monta Vista Capital, and president of The Indus Entrepreneur (TiE), a 21-year-old global nonprofit that promote wealth creation through entrepreneurship. Venk also started a CIO Forum, which connects 25 CIOs from companies such as Costco, WalMart, Clorox, GE Capital, HCA Health Care and others with the most innovative B2B companies in the Valley. In addition, he is the founding chair and active member of TiE Angels, one of the most active Angel investor groups in the Valley with 140 members and 26 investments in the last three years, mostly in the B2B space.

Venk started his career as a civil servant in the equivalent of the IRS in India, after receiving his degree in electronics engineering and working briefly in the Indian Space Research Organization.

Listen to my full interview with Venk here

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Click the links below to hear Venk discuss

Coming to America

“I didn’t want to come to the U.S. My sister was already here but I was having fun in India and I had no ambition (to come here.) My sister was frustrated because she thought every electronics engineer should be in this country. … So what did I do? If you were an ambitious young man in India at that time, Civil Service used to be a massive deal. It still is, but it’s not as big a deal as it used to be in those days. So I took the Civil Service exam. It was an 18-month-long exam process, 24 months actually… At the end of it they pick only about 500 people. And then you’re put in a year and half of training in different stuff. Then you are straightaway put into middle management jobs. If you didn’t come through this program, then it would take you 16, 18 years to get there. … So at the age of 22 or 23, I was investigating corruption charges against the governor of the state where I was posted.

… I continued to have fun until I got married. It was an arranged marriage and my wife was a mechanical engineer here at Berkeley. It turns out that despite all the assurances that I was given, she had absolutely zero intention of moving to India. So essentially we had a decision to make. I always wanted to come to the U.S. to do my MBA, so I compromised and after about 18 months of living apart… I’ll come and do my MBA and then we’ll decide. And that was a big mistake because each step that you take has its logical consequence. … They gave me study leave, they gave me salary during time. I went to the Sloan School at MIT. But then I didn’t have enough money, so I had to borrow money to go to school and once you finished school, if you wanted to go back to civil service in India, but there was no way you could pay back the loan in your entire life. So I said OK, I’ll work here for a while, pay off the loan and then go to India. But once you start working here … it never happened. She won. Basically she won.”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

First encounter with big corporate executive

“I went with my boss to make my very first sales call. (It was) General Dynamics in San Diego, a big defense contractor and the guy that we were meeting, he had a huge table sitting on an elevated platform and we could see him from outside but he would not usher us in. We had to wait until his secretary took us inside and then he acknowledged our existence. And his wall was filled with trophies and guns and this and that, and he was literally sitting one foot above the rest of us on a huge table. At the end of the meeting, when we came out, my boss asked me — I was still under training — “So what kind of a person was he?” He expected to give me this framework – amiable, rational… I said, ‘He was an asshole.’ ”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

What it was like to do a startup

“The first impression, coming from a big company to a startup, was that every single decision that I made on a daily basis had an impact and that was a very, very intoxicating feeling. … Everything that I did had an impact and it was a tangible impact. In a big company when you go through these meetings and meetings and meetings, you feel like you’re a cog in a wheel and the real impact, which is varied, is in terms of product or in terms of customers. You get lost somewhere in between that.”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

What is TiE ?

“In ’92, these 8 or 10 guys who were successful beyond their wildest dreams … all Indians, they got together at the airport because they’d come to meet some minister from India and his flight didn’t show up but they’re at the airport and decided to talk to each other. When they started exchanging notes, they all came to same to the conclusion, that it’s very hard for Indians to get funded.

It’s hard to believe now but in ’92 that was the perception, that Indians make good VPs of technology and CTOs but they should get a professional manager, which typically at that time they’d get a white guy from a big company to be a CEO. … So they started this group with three basic principles; Number one is that wealth creation is a noble activity and coming from India, which is a socialist economy, this was a big statement to make. … Number 2, was that the best way to create wealth is through entrepreneurship. Now, everybody in the world agrees with these two principles. The way TiE was different was really with the third principle, that the best way to promote entrepreneurship is for successful people to roll up their sleeves and help those who aspire to be successful. …There is not other organization in the world that is like TiE right now. …There’s no organization that combines highly successful people with those who want to be successful.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Filed under: SiriusXM Radio Show

July 20, 2015

How we changed the way the U.S. government commercializes science: Errol Arkilic — Part 1 of Episode 6 on Sirius XM Channel 111

My guests on Bay Area Ventures on were:

Errol Arkilic, former program director for the National Science Foundation Innovation Corps (NSF I-Corps), now founder of M34 Capital

Steve Weinstein, CEO of MovieLabs

Venk Shukla, president TiE Silicon Valley and general partner, Monta Vista Capital

In my interview with Errol, we discussed the origins of the National Science Foundation Innovation Corps (I-Corps), how and why it was created, and how it changed the way the government commercializes scientific research. (Read my interviews with Steve Weinstein and Venk Shukla in a separate post to follow.)

—-

Errol Arkilic was the lead program director for the National Science Foundation I-Corps, which uses my Lean LaunchPad curriculum to teach scientists and engineers how to take their technology out of the lab and into the marketplace.  Today he is the founder of M34 Capital, a seed capital fund that focuses on early-stage projects being spun out of academic and corporate research labs.

Today he is the founder of M34 Capital, a seed capital fund that focuses on early-stage projects being spun out of academic and corporate research labs.

Listen to my entire interview with Errol:

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

The Origins of National Science Foundation I-Corps

The I-Corps had a serendipitous start. Errol explains in this clip.

Errol : There was a unique opportunity in 2011 when the new director of National Science Foundation said, ‘We want to do something new and different [in helping scientists commercialize their technology].’ … He charged me .. to put together a mentorship program [for academic scientists]. We floated that around the office for about a week and said there was no way that that’s going to work.

We had to do something different. And right about that time you were publishing your notes to the Lean LaunchPad course in spring of 2011, Stanford, E245. … There was a blog post that you wrote … describing the first class at Stanford. I read it and I ran thing down the hall and said to my colleagues, ‘You’ve got to go read this.’ There was one element of the blog post where you described how you were teaching entrepreneurship like we were teaching art. You were going to give them deep lessons of theory and then you were going to dump them in the deep end, so to speak [and give them experiential practice.] That paragraph really resonated with a bunch of us at NSF, me included.

That was about the same time that Dr. Suresh said we want to do something different. It was a serendipitous moment. …

Steve : …This is the first time I’m hearing the other side of it, … that you actually had a charter .. to do something different. From my side … I wrote the book [The Four Steps to the Epiphany], and while all the theory was in there, you couldn’t just hand somebody the book and expect them to do something. … We needed a way to teach entrepreneurship that was experiential and hands-on. And much like the educational paradigm, I can tell you about it all the time, but if I actually make you do it, it’s going to stick a lot more.

The Lean LaunchPad class.. was an experiment that no one had ever run before. [Up until then] the capstone class – meaning the best class you could take for being an entrepreneur in a university – was how to write a business plan. Yet we all [anyone teaching who actually had founded a company] knew that in all honesty no business plan survives first contact with customers. But nothing else like [The Lean LaunchPad class] was being taught.

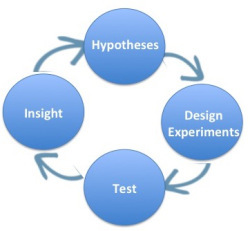

This [Lean LaunchPad class] was to me a major science experiment – having teams come in, write a business model, talk to 10 customers a week, have them present their results every week and actually be testing a series of of hypotheses.

And the blog you were reading, [was created because] I thought that the class was so crazy and different I … wanted to share what I was doing [with other educators]. And since I open source everything I do, you were the recipient of open source. I have to tell you that everybody who knew me said, ‘Steve these are the most boring blogs you’ll ever write. No one cares about a new class, and no one’s going to ever read them.’ The good news is that for any of you who ever wanted to publish something Errol is a great example of what happens if there is only one person who reads what you write. Something magical could happen.

So that’s when you picked up the phone and called.

Errol : That’s right. I picked up the phone and said, ‘I’ve been reading your blog, I’ve been monitoring E245 and said I’ve got a deal for you. I’ve got 10,000 principal investigators and they all have technologies and projects that they think might have commercial potential, and our job is to figure out a way to figure out whether or not here is. Oh by the way, there’s no funding for you.’

Steve : Thank goodness I was already retired and funding didn’t matter. … My memory of the call is that it kind of went, ‘Hi I’m Errol from the NSF,’ and after I said, ‘What’s the NSF?’ After a long pause and explanation, you said, ‘The U.S. government needs your help,’ and I remember saying, ‘The U.S. government already got my help for four years in Vietnam and they’re not getting it again.’ … I kind of remember there was an even longer pause on your end, as I’m assuming you were thinking, “do I have the right or wrong guy at the end of the phone?”

I was ready to hang up on the call until you said there are 10,000 potential scientists [who could be my students.] In my career, the most fun I ever had was working with and selling to people who were doing truly rocket science. I had to learn what they were doing to be able to understand how to sell to them … [so teaching a class for the NSF] was a new opportunity – could I figure out if we could take rocket scientists and teach them the basics of how to build a business.

Errol : And we did. And I think that the principles of the scientific method applied to the commercial opportunity is spot on. That’s what scientists and engineers needed to embrace.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Click on the links below to hear more of Errol’s interview

What made him call Steve?

“A consistent theme we recognized at NSF, was that a lot of the startup companies [we were funding] really weren’t practicing what we knew to be the best and most effective way of taking technologies out of labs. … What we saw were practices that any investor would look at and say there’s got to be a better way of doing it. And it wasn’t exclusive to the [NSF commercialization] program. It was a crappy way [the U.S. government had] of taking technology out of [all of its] labs.”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

How I-Corps Teams are Selected

We started the interview process like most people – [we] asked about the idea and the status of the technology was and got spun up on the story. We pretty quickly identified that was the wrong way to go. Because really what we needed were teams that were totally aligned with one another and could work together under extreme pressure and extreme ambiguity because the ideas change anyway. … The teams that are coming together to investigate their commercial opportunity, they need to look way beyond the technical boundaries of their discipline to see if there is a business there. … The key thing is that we’re trying to take teams on a journey with us and with one anther, and some people are not amenable to change and not amenable to coaching and not amenable to advice.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

How the I-Corps Has Grown

Errol

: The number is up at 550 teams [through the I-Corps classes]. And there’s scale being brought. You and I ran one, we ran two, and then we quickly identified we needed to bring additional Steve Blanks to the table and structure to put in place. We knew we that needed to duplicate the capacity. Stanford loaned us the resources to begin with but we knew that wasn’t in the long term sustainable, so while I was in NSF, we established a program that developed a structure that included a network of academic nodes that teach the course. … We brought on more schools. …

Steve : … If I remember, you and I brought on Georgia Tech, and then University of Michigan and then how many more?

Errol : The group after that is in NY it’s CUNY, NYU and Columbia. In DC it’s George Washington University, the University of Maryland and Virginia Tech, and now Johns Hopkins… in the Bay Area, there’s Berkeley, Stanford and UCSF. … In Southern California, there’s Caltech, USC and UCLA. And in Texas, it’s the University of Texas at Austin, Rice and …

Steve: We’re losing count, but there’s a bunch of them now that started from that phone call. 550 teams; 20 universities [as nodes and another 36 as sites]; must be 30-40-50 instructors now playing Steve Blank. This kind of makes it one of the largest accelerators in the United States, probably up there with TechStars and Y Combinator except it’s a U.S. government accelerator that takes \ no equity. So, Errol, congratulations, you’ve created something wonderful.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Lessons for the Country

I think the strong takeaway is that the commercial considerations must be done in parallel with the technical considerations. It’s not an after thought, it’s not something you come in later and tack on the end. If your goal is to get the technology out of the lab, it’s never too early to start thinking who the customer for that solution is. … If you are a scientist and you think that your science is addressing human needs, you better be talking to some humans. … I think the most rewarding element of the Innovation Corps is when a principle investigator comes back and says, ‘I’m now changing the way I think about crafting my research moving forward.’ That feedback is an incredible demonstration of a significant change.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

What is M34 Capital?

M34 is a fund that focuses on taking Customer Discovery and the Lean Startup process and applying it in the venture model. We look at companies at their earliest stage of development and we believe with our capital that through the approach of the lean process and customer discovery that we can get companies up the learning curve, up the value curve, more effectively than other approaches. … The companies that come out of I-Corps are primed for success but they still need help. That wasn’t surprising to us. We knew that there were gaps that needed to be filled – capital gaps, management gaps, experience gaps and we saw it as an opportunity to get back out and become an entrepreneur again. … We look across the board at any company that has the discipline of customer discovery and Lean and the reason we need that is because it’s just a different way of looking at things. It’s evidence-based, it’s the scientific method and when the company has that on Day Zero, the conversations that we have are just that more meaningful. … If they don’t get it, we’re not touching them. “

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Filed under: SiriusXM Radio Show

July 14, 2015

Episode 1 on Sirius XM Channel 111: Alexander Osterwalder and Oren Jacob

My guests on Bay Area Ventures on were:

– inventor of the Business Model Canvas

Oren Jacob, ex-CTO of Pixar and now CEO of ToyTalk

—–

The focus of our first segment was on Alexander Osterwalder’s Business Model Canvas – how and why he created it and how startups and large companies are using it to search for repeatable, scalable business models.

He is also author of the international best-seller Business Model Generation, and inventor of the management tool, the Business Model Canvas, used by companies like Coca Cola, GE, and LEGO to design, test, build and manage their business models.

Listen to my entire chat with Alexander here:

If you can’t hear the interview, click here

Click the links below to hear Alexander

What’s the Business Model Canvas?

“It’s basically a visual template that allows you to create a shared language and it gets your idea out of your head onto the poster or a piece of paper to make it crystal-clear. … You capture the idea, you tell the story very quickly on one piece of paper. Then the Lean Startup comes in … you take this one piece of paper and then immediately go test it out. You start rough, you test quickly and you refine only when you have more evidence from the market that your idea could work.”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Why Understand Customers?

“We think we need to come up with some kind of prototype first, but first we need to select which customers we’re going to address and we need to deeply understand them. … You don’t want to work for just any kind of customers, but customers that have a budget, that are willing to buy from you. Because at the end of the day a business model only survives if it can be profitable.”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Why Test Your Idea?

“You really need to understand first what customers actually want. Because customers don’t care about your idea. … We tend to fall in love with our ideas, but you need to test your ideas. Do your customers want your value proposition? Do the channels you imagine to reach these customers actually want to work with you? The partners you might need to co-create a product — they might not want to work with you. You need to figure out all these things and you need to get hit by reality very quickly — do a reality check — if your idea could really be turned into a business.”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Why Do Big Companies Use the Business Model Canvas?

“They really want to have a shared language across the company to better describe how they’re creating value for their business and how they’re creating value for their customers.”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

What Are the Surprises When You Work With Big Companies?

“Leadership buy-in is actually not a big issue. Leaders do buy into this and they do want to change the way companies work. The biggest struggle is actually to get the buy-in of middle management — of the people who do the operational work, have huge to do lists, have daily tasks — to get them to adopt a new innovation mindset. … The other thing that still is a surprise to me is that large companies still write business plans for innovation projects. So business plans make a lot of sense in execution, but that they still do this for innovation projects. That blows my mind because … managers who have to do these business plans don’t believe in them. They all know they’re made up. But large companies continue to ask for business plans.”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

—

In our second segment, we’ll talk with Oren Jacob, former CTO of Pixar, now co-founder and CEO of ToyTalk.  Oren talks about what it was like to leave Pixar, where he worked for more than 20 years, to launch a new business.

Oren talks about what it was like to leave Pixar, where he worked for more than 20 years, to launch a new business.

He offers a candid look at the trials of being a startup founder, including what happens when your product doesn’t work as you thought it would.

Listen to my entire chat with Oren here

If you can’t hear the interview, click here

Click the links below to hear Oren discuss

Advice for Changing Career Course

“If I was not in a position where I could spend a couple of months not working … probably the right thing to do was to spend some evenings with a partner of mine to think about what to work on next and try to dabble in some places until something had enough customer validation that I got excited about it. … (however) At some point you kind of just got to quit.”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Where Did the Idea for ToyTalk Come From?:

“ToyTalk came about when my daughter, Toby, was 7 at the time. She was on a Skype call with Grandma using an iPhone 2 or 3. … We got off the Skype call with Grandma. We’re in the playroom in my house and Toby holds the phone, looks me, then looks at all the pile of the toys on the shelf and looks at me again and asks, ‘Daddy can I use this to talk to those?’ ”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

What Was Value Proposition Design?

“Finding what they were looking for their customers and their products and what made sense to them was very important.”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

What Happens When the Product Doesn’t Work?

“In a closed acoustic environment… it’s a brilliant idea. It works perfectly well. … (however) We ended up in several people houses with our talking teddy bear chatting with Oprah on TV — which is funny, but not a product — and we were unable to control the product experience at all. So our product actually broke in testing. … We were actually within four weeks of legitimately launching and we had to actually bury it in a board meeting several weeks before launch. … It was a very difficult day.”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

How Do You Handle a Pivot?

“We met with the company the next morning at 10 am and said, ‘Well, we’re not bringing this to market.’ At the time, as is often the case, the folks you’re working with are sometimes a little bit ahead of where the CEO is and they’re kind like, “Whew that wasn’t going to work anyway.’ … You know it’s the right choice when people nod their head and say ‘Yeah, was a great college try but it needs more time or go somewhere else.’ … By Friday of that week, we had a new idea to head out the door.”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Filed under: Big Companies versus Startups: Durant versus Sloan, Business Model versus Business Plan, Customer Development, SiriusXM Radio Show

July 9, 2015

The 7 Deadly Healthcare Startup Sins

Todd Dunn is the Director of Innovation and runs the Intermountain Healthcare Transformation Lab, which is working to foster innovation in the healthcare industry.  He’s now run several Lean LaunchPad classes and has seen a ton of healthcare startups. Here’s his advice for startups in this space.

He’s now run several Lean LaunchPad classes and has seen a ton of healthcare startups. Here’s his advice for startups in this space.

———

I have spent the last 10 years in the Healthcare space. Over the past couple of years as Director of Innovation for Intermountain Healthcare I’ve mentored and worked with many Healthcare-focused startups. During that time I have seen teams that really seem to understand the industry and those who are relatively uninformed.

Our healthcare system is complex, under intense regulatory pressure, the pressure of the aging population, reimbursement changes, and an oncoming shortage of clinicians, among other challenges. It is in need of innovation on many fronts and is also trying to embrace the amazing amount of innovation happening with early-stage companies.

Yet, I have noticed that many healthcare startups make “leap of faith assumptions” as they try to build their businesses. Let me highlight the 7 deadly healthcare startup sins!

Sin 1: Healthcare startups assume hospitals will let them host patient data in “their portal.” The reality is that healthcare customers know that startups’ portals are likely hosted by AWS, Azure, or Google, and therefore pose security and privacy concerns. My reference points on these startups are digital health startups and small device startups that gather data from patients remotely. Many startups make the key assumption that hospitals will trust their data to a startup’s “cloud” for the long term. For a proof of concept or pilot this may be OK. For the longer term it may not be. The only way to know for sure is to test that assumption by getting out of the office and talking to customers.

Sin 2: Startups assume that clinicians will be willing to access yet another portal for their data. Basically, startups make assumptions about clinicians’ workflow that may be myopic. In completing their Business Model Canvas some startups assume that a clear value is having their solution hosted in the cloud but often overlook the workflow impacts from a value perspective. The challenge is that many of them haven’t done enough “get out of the office” work to understand how their proposed solution will or won’t fit into a healthcare provider’s workflow. Doctors and nurses want more time with patients. In addition, doctors have many data points for making decisions. Having to go to multiple places for data about one patient reduces the time they can spend with each patient and complicates sound decision-making. The “job to be done” is to diagnose and prescribe. One pain that doctors and nurses want to avoid is going to multiple locations to get the needed decision support data. Clinical decision support needs to be simplified. Going to another portal for patient data is simply onerous. If your solution reduces the time a clinician can spend with a patient or makes it harder to make a decision you have reduced the value.

Sin 3: That one doctor or hospital lends enough credibility for other organizations to simply accept a startup’s solution. Many startups believe that if they have a doctor on their team or as an advisor (the idea of having a KOL – Key Opinion Leader), or if one hospital has written a letter of support, they have credibility. The reality is that it doesn’t suffice. More homework needs to be done. Healthcare regulations, processes, and delivery approaches often vary from system to system. A broader base of KOL’s would simply lend credibility to the solution’s applicability across multiple customers. “Getting out of the office” and talking to customers is a necessary endeavor to get these deep and broad insights from KOL’s.

I recommend that teams get a least five KOL’s to support their value claims. This isn’t just about conducting 100 customer interviews. This is about getting evidence that Key Opinion Leaders agree that the value proposition offered by the startup can be realized. As Steve recommends, use an MVP to get evidence that validates those opinions.

Sin 4: Believing that ONE key leader inside a hospital is the decision-maker, influencer, etc. all in one role…. The Startup Owner’s Manual clearly articulates the need to understand “how” a company buys a product. ….Most startups I see want to go directly into a pilot and many want to speak directly with the C-level clinical leaders. Part of the weakness is that most startups aren’t asking learning questions … they are making statements vs. being curious enough to test their assumptions.

Sin 5: Thinking that conducting a “proof of concept” and/or pilot is a simple endeavor. In working with eight early-stage companies in the last two months I have consistently asked, “What do you want from us?” Oddly I found some teams did not have a crisp answer. However, all of them wanted to hop directly into a proof of concept within an extremely short time. In wanting to do so, they overlooked

the need for an IRB (institutional review board,) (especially where patients are involved)

a security review (especially if they are in “the cloud”)

a compliance review

the time needed to design a study

and last but not least signing a contract!

All of these are easily in the “Activity” portion of the Business Model Canvas and few early-stage companies fully understand these needs, especially when working with a large IDN (integrated delivery network) like Intermountain Healthcare.

Sin 6: There isn’t anyone else out there solving the problem. A large percentage of startups struggle to answer the question, “Why do current solutions fail?” This suggests that they haven’t completed a petal diagram to look at the existing offerings, or analyzed the “job” that someone needs to hire a solution for. As an example, a med-adherence solution approached us recently and offered that there wasn’t “anyone” else with a technology like theirs. That may be true…not likely. I suggest that teams thoroughly think through this.

Sin 7: Believing that startups need to have more answers than questions. Almost unanimously startup teams want to have an answer for every question. I understand their desire to appear knowledgeable. But you don’t get out of the office to have answers – you get out of the office to ask questions. This goes back to a fundamental that I believe all startups need until they truly know: curiosity.

My advice to healthcare startups.

My advice to healthcare startups.

Use the Lean Startup tools! Regardless of where you start, it comes down to your value proposition as a starter or non-starter. Use Alexander Osterwalder’s Value Proposition canvas and Steve’s guidance to “get out of the office.”

This often tries the patience of entrepreneurs. I cannot overemphasize the need to use the learning loop in every single part of the Value Proposition and Business Model canvases. The only way to do that is to GET OUT OF THE OFFICE!

Be curious about workflow and how large IDNs (integrated delivery network) like Intermountain Healthcare are thinking about the integration of patient data into a workflow. Be empathetic to your user.

Study the industry more deeply. While you may have a great value proposition for one or two hospitals, how does your solution fit into the regulatory landscape, workflow, etc. of multiple hospitals?

Listen! Assume you don’t have enough evidence to scale your business yet. Act like you don’t know enough. While an entepreneur’s “go get ’em” attitude is appreciated, it isn’t appreciated when the entrepreneur isn’t open to feedback, seems to have all the answers, and has a condescending attitude toward the way “jobs” get done today. Test your assumptions! Come loaded with questions that are related to your assumptions.

Last but not least, structure a learning plan. Embrace the Lean Startup tools and methods. Following this structure will cause you to write a learning plan. A foundational question to guide your learning plan in every part of your business model is “What do we need to learn before we invest more time and money?”

Best of success! Healthcare needs innovative startups and innovative startups need the knowledge and access that Healthcare can provide.

Filed under: Customer Development, Life Sciences (NIH)

July 7, 2015

Hear how the Lean Startup began — and helped one company find success: Episode 2 on Sirius XM Channel 111: Eric Ries and Jon Sebastiani

My guests  on Bay Area Ventures on were:

on Bay Area Ventures on were:

Eric Ries, entrepreneur and author of the New York Times bestseller, The Lean Startup. Eric was the very first practitioner of my Customer Development methodology which became the core of the the Lean methodology.

Jon Sebastiani, founder and CEO of KRAVE Jerky, a company that got its start in my class at Berkeley back in 2011 and was recently acquired by Hershey.

The focus of our first segment with Eric was, “What is the Lean Startup” and how did it start?

Eric Ries co-founded Catalyst Recruiting while attending Yale, and continued his entrepreneurial career as a Senior Software Engineer at There.com. He later co-founded and served as CTO of IMVU and then authored The Lean Startup. Named one of BusinessWeek’s Best Young Entrepreneurs of Tech, Eric served as a venture advisor at Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers before moving on to advise startups and venture capital firms independently. He was named entrepreneur-in-residence at Harvard Business School in 2010 and is currently an IDEO Fellow.

Listen to my entire chat with Eric:

If you can’t hear the interview, click here

Taking My Class

Back in 2004 when Eric and his IMVU co-founder Will Harvey approached me about investing in IMVU, I agreed on one condition – they had to take my Customer Development class at UC Berkeley Haas Business School.

Hear Eric explain what they learned.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Origins of the Lean Startup

Steve

: Will Harvey, the [IMVU] CEO had asked me to fund his next company … and I put a requirement on Will and you. Can you remember what that requirement was?

Eric : …We had just lost an awful lot of Steve’s money screwing up in the worst and most publicly possible way, going off with our tails between our legs and being total failures. … And we had the audacity to go back to Steve and say, “Listen we just lost you all this money, we’re giant failures, how would you feel about funding our next startup?” … unlike most of the time this happens in Silicon Valley, Steve had a suggestion, a very politely delivered suggestion that … he had just started teaching a class on something he that called customer development. …and he said, ‘Well if you’ll come and audit my class, then I’ll agree to be in [fund] your company.’ And at the time we thought well that’s a pretty good deal. We’ll have to waste a couple of hours a week in Steve’s class, but hey we need the money so what’s the big deal.

Steve: And the entire world who was interested in this process consisted of me and maybe my cat.

Eric : … So my cofounder and I would be in the car we would be arguing about all the things that would be going wrong in our startup and all the things we had to do all the way down to Steve’s class. It was like an hour and half in Bay Area traffic. We’d get there and listen to Steve’s lecture and then we would have a whole hour and a half going back to argue about now what was that thing that Steve just said and of course would couldn’t agree an hour later what it exactly was because it was so different…. I remember, Steve, that you had a line that stuck with me that first time I’ve heard it — — which is that we should have in marketing a methodology as rigorous for making decisions as we have in engineering, I couldn’t understand but I knew it was important because I lived through these startups that fundamentally failed because they had no customers. So that was the big insight of customer development, to take what had previously been a highly monolithic and faith-based initiative of marketing and turn it into a rigorous scientific approach to discover what are the facts about customers.

Steve: And do you remember — I’m going to change your grade if you don’t — about where do the facts reside?

Eric : All the facts reside outside the building.

—

Click the links below to hear more of Eric’s interview

On Being the First Practitioner of Lean: “For me the challenge was how do you systematize this and turn it into a management practice that actually does not just have people pay lip service to it but really actually do it.”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

—

On Agile Development: “We get customers involved in the development of products as soon as possible and to build everything in an experimental way so that we treat every feature, every ounce of energy that we invest in our startup as an experiment to help us understand what our customers really want.”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

—

On Failure as Experience: “I thought that I would not to be able to get a good job because I had this big stinking failure on my resume. I was flabbergasted – almost stunned — to discover that in Silicon Valley all kinds of people looked at that resume and said, ‘Hey you’ve learned a lot of important lessons on someone else’s dime.’ That’s part of the magic of Silicon Valley.”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

—

On Getting Another Chance: “I would have paid for the privilege to work in the legendary place called Silicon Valley. I couldn’t believe this was my opportunity.”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

—

In this second segment Jon Sebastiani talks about his experience founding and developing KRAVE Jerky into one of the fastest growing consumer packaged goods in the country, and how he handled the triumphs and failures he met along the way.

Before founding KRAVE, Jon teamed with his family to steer their Viansa Winery toward becoming one of California’s top winery destinations. He also launched 14 retail stores in 12 states that marketed and sold Viansa wines and foods, and spent a year as Managing Director of wine.com assisting in the turnaround toward its first profitable quarter. KRAVE, which was acquired earlier this year by Hershey for >$200 million, was recently named Forbes Magazine’s Top 25 Most Innovative Companies in the US, and ranked #72 in the Inc. 500 Fastest Growing Private Companies.

Listen to my entire chat with Jon:

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

—

Click on the links to hear Jon discuss:

How Entrepreneurs Are Opportunistic: “It’s a state of mind to constantly look for that area of opportunity and disruption.”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

—

Dealing With Failure: “It was a very humbling experience. … It feels awful. It’s a very lonely feeling.”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

—

The Idea for Krave Jerky: “This moment of serendipity came together that as I was training for the marathon, as I was eating jerky, it struck me as this vacuum of opportunity.”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

—

When the Idea Became a Business: “We started to ask ourselves, ‘Who is our customer? Is it Whole Foods or is it 7-Eleven. Are we Wal-Mart or are we Draeger’s Supermarket?’ And it really started helping me refine my channel strategy of how we were going to roll out this business and how where we were sold really influenced the brand and the image that we wanted to create.”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

—

When The Sale of a Lifetime and Crisis Collide: “It was an amazing serendipitous moment that we were able to get the partner, Safeway Corporation, to completely believe in the positioning of the brand and the product, and as a startup company the only way we could fulfill their PO is for them to pay us in advance so we could actually build that inventory. And it was obviously a game-changer for KRAVE. It put us on the map.”

At the same time, the jerky manufacturer they had designed their first flavors with decided to make their own jerky. To fill Safeway’s order, “We were cold-calling anybody that we made anything to do with meat … pleading with them to consider making our products for us. “

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Filed under: SiriusXM Radio Show

July 2, 2015

Episode 5 on Sirius XM Channel 111: Pete Newell, John Kuhn, Matt Weingart, Takashi Tsutsmi and Masato Iino

My guests this past week on Bay Area Ventures on were:

Pete Newell, managing partner of BMNT Partners

John Kuhn, who works at BMNT Partners

Matt Weingart, program development manager in the Strategic Development Office at the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

Takashi Tsutsumi and Masato Iino, founders of Learning Entrepreneur’s Lab in Japan

The focus of our first segment is how Silicon Valley and the U.S. military can work together – for access to advanced technology and to learn how to move with agility, speed and urgency. Our guests Pete Newell, John Kuhn and Matt Weingart served for decades in the U.S. military and are now helping government agencies operate with the speed and urgency of Silicon Valley.

Pete Newell retired from the US Army in 2013 as the director of the Rapid Equipping Force (REF), responsible for rapidly understanding problems of soldiers in combat and rapidly providing solutions.  Pete directed the investment of over $1.4B to these efforts over a three-year period. He was named by Defense News as one of the 100 most influential people in the defense industry in 2012. (Read the Stanford case study about the Rapid Equipping Force.) Pete is managing partner for BMNT Partners and serves on the Board of Directors for Solace Power and Savonix. He is a frequent contributor to Defense Innovation studies, is a member of the Center for a New American Security’s Beyond Offset Working Group and most recently supported a study on Defense Innovation for the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Pete directed the investment of over $1.4B to these efforts over a three-year period. He was named by Defense News as one of the 100 most influential people in the defense industry in 2012. (Read the Stanford case study about the Rapid Equipping Force.) Pete is managing partner for BMNT Partners and serves on the Board of Directors for Solace Power and Savonix. He is a frequent contributor to Defense Innovation studies, is a member of the Center for a New American Security’s Beyond Offset Working Group and most recently supported a study on Defense Innovation for the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Listen to my entire chat with Pete

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

—

Or, click on the links to hear Pete discuss:

If you can’t hear Pete discuss Meeting the Army Robotics Guy, click here

—

If you can’t hear Pete discuss the Origin of the Army’s REF, click here

—

If you can’t hear Pete discuss What BMNT Does, click here

—

If you can’t hear Pete discuss Talk About the Problem Not the Technology, click here

—

John Kuhn served 20 years in U.S. Army special operations before retiring from active duty service in 2014.  During his military career he served in Bosnia, Afghanistan, Iraq, the Arabian peninsula, Egypt, and the Horn of Africa. John was awarded the Silver Star; six Bronze Stars, including one for valor; an Army Commendation Medal for valor; and two Purple Hearts. John recently co-founded P360, a business that produces animated training content for the military, and he works for BMNT Partners.

During his military career he served in Bosnia, Afghanistan, Iraq, the Arabian peninsula, Egypt, and the Horn of Africa. John was awarded the Silver Star; six Bronze Stars, including one for valor; an Army Commendation Medal for valor; and two Purple Hearts. John recently co-founded P360, a business that produces animated training content for the military, and he works for BMNT Partners.

Listen to my entire chat with John

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

—

Or, click the links below to hear John discuss

If you can’t hear John discuss Military Skills that Translate, click here

—

If you can’t hear Hacking for Defense Explained, click here

—

If you can’t hear John discuss his Business to Government class, click here

—

If you can’t hear John discuss his Advice for Other Veterans, click here

Matt Weingart is a program development manager in the Strategic Development Office at the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. He connects the Lab with the defense user community. His responsibilities include establishing the partnership frameworks between government, private sector, and academia needed to deliver end-use solutions to national security challenges (cybersecurity, undersea warfare, communications, etc.)

Listen to my entire chat with Matt

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

—

Or, click on the links below to hear Matt discuss

If you can’t hear Matt discuss Defense Valley, click here

—

If you can’t hear Matt discuss Self-Selecting Like an Entrepreneur, click here

—

If you can’t hear Matt discuss The Nation is Upside Down, click here

—

If you can’t hear Matt discuss Strategic Deterrence, click here

—

If you can’t hear Matt discuss Grist for the Innovation Mill, click here

In this second segment, Takashi Tsutsumi and Masato Iino talk about how they brought the Lean Startup to Japan. Today they are helping large companies in Japan relearn how to innovate at speed.

Takashi Tsutsumi has been a venture capitalist 15 years incubating and investing in startups in Japan. Prior to that, he worked for an integrated trading company in which he built several new businesses by collaborating with high-tech startups in California.

Masato Iino has been entrepreneur of a couple of startups and an investor for the last twenty years. Prior to that, he worked for the Industrial Bank of Japan and General Electric specializing in deliberative trading, private equity investment, and post merger integration.

Takashi and Masato founded Learning Entrepreneur’s Lab (LEL) in 2014. This seed accelerator uses my Lean LaunchPad class to help incubate startups as well as create new business for enterprises in Japan. Learning Entrepreneur’s Lab is the leader in evangelizing Customer Development/Lean Startup in Japan, being active in lecturing and publishing books including Japanese translations of my books, The Four Steps to the Epiphany and The Startup Owner’s Manual.

Takashi and Masato founded Learning Entrepreneur’s Lab (LEL) in 2014. This seed accelerator uses my Lean LaunchPad class to help incubate startups as well as create new business for enterprises in Japan. Learning Entrepreneur’s Lab is the leader in evangelizing Customer Development/Lean Startup in Japan, being active in lecturing and publishing books including Japanese translations of my books, The Four Steps to the Epiphany and The Startup Owner’s Manual.

Listen to my entire chat with Takashi and Masato

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

—

Or, click on the links below to hear them discuss

If you can’t hear Tsutsumi and Masato discuss Going Lean In Japan, click here

—

If you can’t hear Tsutsumi and Masato discuss Lean in Large Companies in Japan, click here

—

If you can’t hear Tsutsumi and Masato discuss How Failure is Regarded in Japan, click here

—

If you can’t hear Tsutsumi and Masato discuss What Doesn’t Translate for Startups in Japan, click here

Filed under: SiriusXM Radio Show

June 26, 2015

Lean Innovation Management – Making Corporate Innovation Work

I’ve been working with large companies and the U.S. government to help them innovate faster– not just kind of fast, but 10x the number of initiatives in 1/5 the time. A 50x speedup kind of fast.

Here’s how.

—–

Lean Innovation Management

In the last five years “Lean Startup” methodologies have enabled entrepreneurs to efficiently build a startup by searching for product/market fit rather than blindly trying to execute. Companies pursuing innovation can Buy, Build, Partner or use Open Innovation. But trying to find a unified theory of innovation that allows established companies to innovate internally with the speed and urgency of startups has eluded our grasp.

The first time a few brave corporate innovators tried to overlay the Lean tools and techniques that work in early-stage startups in an existing corporation, the result was chaos, confusion, frustration and ultimately, failure. They ended up with “Innovation Theater” – great projects, wonderful press releases about how innovative the company is – but no real substantive change in product trajectory.

—-

In working with Greg Hannon, the head of Innovation at W.L. Gore, I’ve found two corporate strategy tools developed by other smart people helpful in bridging Lean Startups with Corporate Innovation. The first, the notion of the “ambidextrous organization” from O’Reilly and Tushman, posits that companies that want to do continuous innovation need to execute their core business model while innovating in parallel. In other words, in an ambidextrous company you need to be able to “chew gum and walk at the same time.”

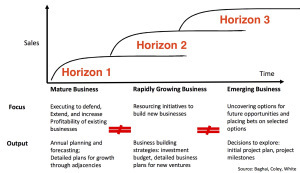

The second big idea of corporate innovation is the “Three Horizons of Innovation” from Baghai, Coley and White. They suggest that a company allocate its innovations across three categories called “Horizons.”

Horizon 1 are mature businesses.

Horizon 2 are rapidly growing businesses.

Horizon 3 are emerging businesses.

Each horizon requires different focus, different management, different tools and different goals.

The Three Horizons provided an incredibly useful taxonomy. However in practice most companies treated the Three Horizons like they are simply incremental execution of the same business model.

While these theories explain how to think about innovation in a company they didn’t tell you how to make it happen.

Fast forward to today. To move innovation faster, we now have 21st century tools —Business Model Canvas, Customer Development, Agile Engineering – all adding up to a Lean Startup. We can adapt these startup tools for use inside the corporation.

To do so we’ll keep the concept of three unique horizons of innovation but reframe and combine them with what we’ve learned about Lean Startups. The result will be:

To do so we’ll keep the concept of three unique horizons of innovation but reframe and combine them with what we’ve learned about Lean Startups. The result will be:

a new, Lean version of the Three Horizons of Innovation

an ambidextrous company, and

a way for existing organizations to build and test new ideas at blinding speed.

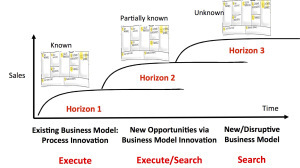

The Lean Definition of the Three Horizons of Innovation

In this new model, the Horizon level of innovation is defined by whether the business model is being executed or searched for.

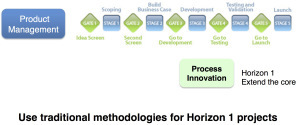

Horizon 1 activities support existing business models.

Horizon 2 is focused on extending existing businesses with partially known business models

Horizon 3 is focused on unknown business models.

Horizon 1 is the company’s core business. Here the company executes a known business model (known customers, product features, competitors, pricing, distribution channel, supply chain, etc.) It uses existing capabilities and has low risk in getting the next product out the door. Management in this Horizon 1 works by building repeatable and scalable processes, procedures, incentives and KPI’s to execute and measure the business model. (And if they’re smart they’ll teach Horizon 1 teams to operate with mission and intent, not just process and procedure.)

Innovation and improvement occurs in Horizon 1 on process, procedures, costs, etc. Product management for Horizon 1 uses existing product management tools such as StageGate® or the equivalent.

In Horizon 2 a company extends its core business. Here the company looks for new opportunities in its existing business model (trying a different distribution channel, using the same technology with new customers or selling existing customers new products, etc.) Horizon 2 uses mostly existing capabilities and has moderate risk in getting new capabilities to get the product out the door. Management in Horizon 2 works by pattern recognition and experimentation inside the current business model.

Horizon 3 is where companies put their crazy entrepreneurs. (Inside of companies these are the mavericks you want to fire for not getting with program. In a startup they’d be the founding CEO.) These innovators want to create new and potentially disruptive business models. Here the company is essentially incubating a startup. They operate with speed and urgency to find a repeatable and scalable business model. Horizon 3 groups need to be physically separate from operating divisions (in a corporate incubator, or their own facility.) And they need their own plans, procedures, policies, incentives and KPI’s different from those in Horizon 1.

Product management for Horizon 2 and 3 uses existing Lean Innovation Management tools such as Lean LaunchPad®, the NSF I-Corps™ or the equivalent.  Using these tools internally a company can get startup speed and urgency. Horizon 3 organizations organized as small (

Using these tools internally a company can get startup speed and urgency. Horizon 3 organizations organized as small (

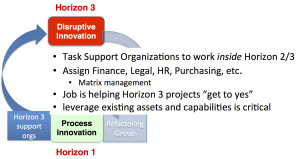

Get to Yes

Horizon 2 and 3 activities are not entirely separated from the corporate structure.  To help Horizon 2 and 3 organizations navigate all the processes, procedures and metrics the company has built to support Horizon 1 activities, individuals from support organizations (legal, finance, procurement, etc.) are assigned to work inside Horizon 3 organizations. Their function is to help Horizon 2 and 3 organizations navigate to a “Yes” inside the company.

To help Horizon 2 and 3 organizations navigate all the processes, procedures and metrics the company has built to support Horizon 1 activities, individuals from support organizations (legal, finance, procurement, etc.) are assigned to work inside Horizon 3 organizations. Their function is to help Horizon 2 and 3 organizations navigate to a “Yes” inside the company.

Horizon 1 operates on goals and incentives. And Horizon 1 managers need to be incented to embrace and support innovation going on in Horizons 2 and 3. Companies need their Horizon 1 managers to both encourage mavericks to propose projects, as well as to support mavericks and then incentive for adoption and scale of Horizon 3 projects.

If supporting Horizon 2/3 is not part of Horizon 1 goals and incentives, then there is no real commitment to corporate innovation.

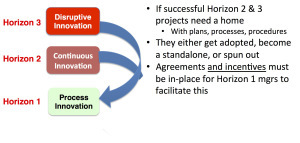

Oh no! Yes! We’ve Succeeded

What happens to successful innovations from Horizons 2 and 3?  They either get adopted by a Horizon 1 organization (a division, P&L, functional organization,) they reach a size large enough to become a standalone group or they can be sold/spun out. To make this work Horizon 1 execs and managers need incentives and job descriptions to support Horizon 2 and 3 activiities.

They either get adopted by a Horizon 1 organization (a division, P&L, functional organization,) they reach a size large enough to become a standalone group or they can be sold/spun out. To make this work Horizon 1 execs and managers need incentives and job descriptions to support Horizon 2 and 3 activiities.

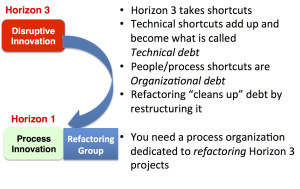

One of the biggest complaints from Horizon 1 managers is that successful Horizon 3 innovation projects leave a mess of technical and organization debt that a Horizon 1 organization has to clean up.  This isn’t some exception; in fact it’s a natural part of corporate innovation.

This isn’t some exception; in fact it’s a natural part of corporate innovation.

What is missing is the realization that there needs to be a dedicated corporate group to refactor (cleanup) the debt from successful innovation projects.

Do it Again!?

When a Horizon 2 or 3 program finds success, it can either grow on its own (and hence become their own divisions) or the founders and early employees may get folded back into a Horizon 1 organization that will scale the program. Typically this is a bad idea for all involved. In short-sighted companies the Horizon 2 and 3 innovators get frustrated, and leave.  In far-sighted companies they get to start a new cycle of disruptive innovation.

In far-sighted companies they get to start a new cycle of disruptive innovation.

Lean Is the Language of Corporate Innovation

We have a common language and process for execution–product management tools, financial reporting etc. Yet we have no common language and process for innovation and searching for business models.

We can adopt the Lean Vocabulary–Business Model Canvas, Customer Development, Hypotheses, Pivots and Minimum Viable Products and Evidence-based entrepreneurship as the corporate language of “search versus execution.” And we can use Lean Metrics (Investment Readiness Level and Technology Readiness Levels) and Lean Portfolio management tools to provide rigor to go/no go funding decisions. Finally we can use the open-source lean classes from the National Science Foundation I-Corps and the Stanford/Berkeley Lean LaunchPad classes to run Horizon 3 projects.

Lean is The Engine for the Ambidextrous Organization

An ambidextrous company runs large numbers of Horizon 2 and 3 projects simultaneously while relentlessly improving the way it executes its current business model and serves its existing customers. This happens when the C-level executives share a common strategic intent, a common vision, explicit values and identity, and they are compensated for both execution of the current business model and the search for new ones. They also realize that operating at all three horizons will require them to tolerate and resolve conflicts.

Lessons Learned

Corporate Innovation needs Lean tools

When combined with the business model canvas, the Three Horizons of Innovation provide a framework for corporate innovation

Horizon 2 and 3 (new/disruptive innovation) are run with Lean Startup speed and organization

Lean Innovation management combines Three Horizons of Innovation with the Lean Startup to deliver an Ambidextrous Organization

The entire organization must be incented to value and embrace not only continuous improvement but also successful innovations

Result: 10x the number of initiatives in 1/5 the time

Filed under: Big Companies versus Startups: Durant versus Sloan, Customer Development, Science and Industrial Policy

May 19, 2015

Organizational Debt is like Technical debt – but worse

Startups focus on speed since they are burning cash every day as they search for product/market fit. But over time code/hardware written/built to validate hypotheses and find early customers can become unwieldy, difficult to maintain and incapable of scaling. These shortcuts add up and become what is called technical debt. And the size of the problem increases with the success of the company.

You fix technical debt by refactoring, going into the existing code and “cleaning it up” by restructuring it. This work adds no features visible to a user but makes the code stable and understandable.

While technical debt is an understood problem, it turns out startups also accrue another kind of debt – one that can kill the company even quicker – organizational debt. Organizational debt is all the people/culture compromises made to “just get it done” in the early stages of a startup.

Just when things should be going great, organizational debt can turn a growing company into a chaotic nightmare.

Growing companies need to understand how to recognize and “refactor” organizational debt.