Steve Blank's Blog, page 35

September 25, 2014

Watching Larry Ellison become Larry Ellison — The DNA of a Winner

In Oracle’s early days Kathryn Gould was the founding VP of Marketing, working there from 1982 to 1984. When I heard that Larry Ellison was stepping down as Oracle’s CEO I asked Kathryn to think about the skills she saw in a young Larry Ellison that might make today’s founders winners.

—

Though I haven’t talked to Larry face-to-face for 20 years, and haven’t worked at Oracle for 30 years, he’s the yardstick I’ve used to pick entrepreneurs all of these years since.

Larry had the DNA I’ve seen common with all the successful entrepreneurs I’ve backed in my 25 years of Venture Capital work—only he had a more exaggerated case than most. Without a doubt, Larry was the most potent entrepreneur I’ve known. It was a gift to be able to work with him and see him in action.

Here’s what was exceptional about Larry:

Potent Leadership Skill

Larry didn’t practice any kind of textbook management, but he was an intense communicator and inspiring leader. As a result, every person in the company knew what the goal was—world domination and death to all competitors. He often said, “It’s not enough to win—all others must fail.” And he meant it, but with a laugh.

It wasn’t as heavy as it sounds, but everyone got the point. We were relentless competitors. Even as the company grew from a handful of people when I started to about 150 when I left (yes, still ridiculously small) I observed that, every single person knew our mission.

This is not usual—startups that fail often have a lot of people milling around who don’t know what the goal is. In winning companies, everybody pulls in the same direction.

1978: Ed Oates, Bruce Scott, Bob Miner and Larry Ellison celebrate Oracle’s first anniversary

1978: Ed Oates, Bruce Scott, Bob Miner and Larry Ellison celebrate Oracle’s first anniversary

A corollary to Larry’s leadership style was that, at least in my day, he did it with great humor, lots of off-the-cuff funny stuff. He loved to argue, often engaging one of our talented VPs who had been captain of his school debate team. When we weren’t arguing intensely, we were laughing. It made the long hours pass lightly.

Huge Technical Vision

Larry always had a 10-year technical vision that he could draw on the whiteboard or spin like a yarn.

It wasn’t always perfect, but it was way more right than wrong, It informed our product development to a great degree and kept us working on more or less the right stuff. Back then he advocated for

Portability (databases had previously been shackled to the specific machines they ran on)

Being distributed/network ready (even though Ethernet was just barely coming into use in the enterprise)

The choice of the SQL a way to ask questions (queries) in an easy-to-understand language

Relational architecture (a collection of data organized as a set of formally described tables) in the first place—all new stuff, and technically compelling

The final proof of a compelling technical vision is that customers were interested—the phone was always ringing. Often it was people cold calling us, who had read something in a trade magazine and wanted to know more. What a gift! Not every startup gets to have this—but if you don’t, you’ve got a problem.

Pragmatic and Lean

Larry ascribed to the adage, “We don’t do things right, we do the right things.” I’m not sure if he ever actually said that, but it is what he lived.

In a startup you can’t do a great job of everything, you have to prioritize what is critically important, and what is “nice to have.” Larry didn’t waste time on “nice to have.”

I am a reformed perfectionist (reformed after those days) so often this didn’t sit well with me. I now realize it was the wisdom of a great entrepreneur. Basically if you didn’t code or sell, you were semi-worthless. (Which is why I had OEM sales as part of marketing—we had to earn our keep.)

This philosophy extended to all aspects of the company. We always had nice offices, but we didn’t mind crowding in. When I started we were in a small suite at 3000 Sand Hill Road. I would come to the office in the morning and clean up the junk food from the programmer who used my work area all night. This was cool!

Oh, and I should say, even though we were at 3000 Sand Hill, VCs kind of ignored us. They thought we were a little nuts. It took a long time for our market to develop, so Oracle wasn’t exactly a growth explosion in the early days. There we were, right under their noses!

Larry was loathe to sell any of the company stock; he generally took a dim view of VCs and preferred to bootstrap. (Sequoia Capital eventually invested just a little in us). Angel investor Don Lucas had his office above ours. I remember Larry telling me that every time we borrowed his conference room we had to pay Don $50. I’m not sure it’s true, but it’s what Larry said. I wonder if he took stock or cash.

Irresistible Salesmanship

Larry wasn’t always selling, didn’t even like salespeople half the time, but boy, when he decided to sell, he was unbeatable.

I’ll never forget sitting in an impressive conference room at a very large computer manufacturer that was prepared to not be all that interested in what we had to say.

Larry just blew them away. They had to re-evaluate their view on their database offering—and they eventually became a huge customer.

He reeled out that technical vision, described the product architecture in a way that computer science people found compelling and turned on the charm. It was neat to be in the room. I saw this a lot with Larry; the performance was repeated many times.

Hired the Smartest People

The old adage “A players hire A players, and B players hire C players” applies here. Larry often philosophized that we couldn’t hire people with software experience because there were hardly any software companies, so we just had to get the smartest bastards we could, and they’d figure it out.

I think he was particularly skilled at applying this to the technical team.

I remember a brilliant young programmer whom Larry allowed to live anywhere he wanted in the US or Canada, didn’t care about hours, where he was or any of that stuff. We just got him a network connection and that was it. This was unheard of back then, but we did it fairly often to get superstars. I remember when we hired Tom Siebel—Larry was so excited, telling me about this deadly smart guy we just hired in Chicago who was sitting in our conference room that very minute! I had to go meet him!

I should say that Larry looked for smarts in men and women—women have always had the opportunity to excel at Oracle. And now there’s Safra Catz—whom I never met, but even back in the ’80s I remember Larry telling me how smart she was.

He Had Some Quirks

Larry would sometimes take time out to think. He would just disappear for a few days, often without telling marketing people (who may have scheduled him for a press interview or a customer visit!), and return re-charged with a pile of ideas—many good, some not so much.

He liked to experiment with novel management ideas, like competing teams. He would set up some people to develop a product or go after a customer or whatever, and have competing teams trying to do the same thing. It’s always fun to experiment, though I never saw one of these fiascos succeed.

I remember one time he had his cowboy boots up on the desk, saying that we’d be bigger than Cullinet and we’d do it with 50 people, and only one salesperson. He was getting high on ideas. Only a computer historian would know Cullinet, an ancient database company that made it to $100M in sales back in the early ’80s. Yes, he was right about “bigger than Cullnet.” The “50 people” was motivated by his dream that we could just have the very, very best developers in the world, and hardly any salespeople—it was just talk. I think he came to appreciate the sales culture later on.

Larry loved to be called “ruthless.” When I asked what was his favorite book, he told me Robber Barons — worth a read even today! And he used to pore over spec sheets for fancy jets he probably thought he could never afford. Funny, I never heard him talk about sailing back then.

I’m not sure how all of this played out later because I wasn’t there. But it was clear, even back in those early days, that Larry had it all: leadership, technical vision, pragmatism, personal salesmanship, frugality, humor, desire to succeed.

I have to think my success in the VC business was due in no small part to seeing Larry Ellison in action back in the day.

Lessons Learned

Great entrepreneurial DNA is comprised of leadership; technological vision; frugality; and the desire to succeed. World-class founders:

Have a clear mission and inspire everyone to live it every day

Are the best salesman in the company

Hire the smartest people

Have a technological vision and the ability to convince others that it’s the right thing

Know it’s about winning customers and don’t spend money on things that aren’t mission-critical

Are relentless in pursuit of their goals and never take NO for an answer

Know humor is powerful — and fun!

Filed under: Technology, Venture Capital

September 23, 2014

The Woodstock of K-12 Education

Describing something as the “Woodstock of…” has taken to mean a one-of-a-kind historic gathering. It happened recently when a group of educators came to the ranch to learn how to teach Lean entrepreneurship to K-12 students.

—

We Can Do Better than Teaching Students How to Run a Lemonade Stand

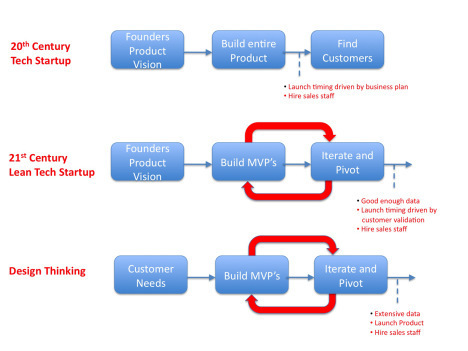

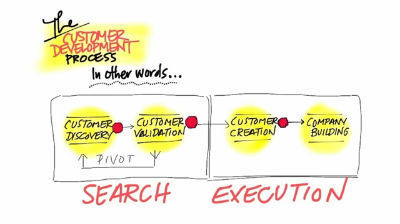

Over the last few years it’s become clear that the days of teaching “how to write a business plan” as the cornerstone of university entrepreneurship are over. We now understand the distinction between startups – who search for a business model – versus existing companies – that execute a business plan. Learning how to keep track of inventory and cash flow and creating an income statement and a balance sheet are great skills to learn for managing existing businesses.

But to teach startup entrepreneurship we need to teach students new skills. They need to learn to find answers to questions like: who are my customers, what product features match customer needs, how do I create demand and what metrics matter? Learning these skills requires a very different type of entrepreneurship class, best taught through a hands-on, team-based, experiential approach. (The Lean LaunchPad/I-Corps class is the canonical model of such a class, with versions now taught in hundreds of colleges and universities.)

In addition, most programs fail to teach students the distinction between a lifestyle business, small business and scalable startup. While the core principles of lean work the same for building a small business versus a scalable startup, there is a big difference between size, scaling, risk, financing, decision-making, uncertainty, teams, etc.

Entrepreneurial education in grades K-12, if it exists at all still focuses on teaching potential entrepreneurs small business entrepreneurship – the equivalent of “how to run a lemonade stand.” This is fine if what we want to do is prepare our 21st-century students to run small businesses (a valid option), but it does real damage when students leave entrepreneurship classes thinking they’ve learned something about how entrepreneurs who build scalable startups think and operate.

On Fire With A Vision

In 2013, after taking the 2½-day “Lean LaunchPad for Educators” seminar, a few brave educators from Hawken School, a K-12 school in Cleveland, Ohio, decided to change the status quo. They returned to Hawken on fire with a vision of building a completely different sort of entrepreneurship course in their school. They saw the future was a course where students would learn by working on actual problems in the real world instead of sitting in a lecture hall. They adopted the Lean LaunchPad methodology because, as they said, it provides a framework for the chaos of a startup, where nothing is predictable. They found that they could approach teaching entrepreneurship like the scientific method. They ask their students to develop hypotheses and then get out of the classroom to conduct interviews to test them. They learn techniques for innovation, analytical approaches to research, and evidence-based systems for decision-making and problem-solving.

Teaching Other K-12 Educators

I had blogged about what Hawken learned implementing something this radical in High School here, and in middle school here. (Take a minute to look at the posts for context.) Honestly, I had never expected the Lean LaunchPad class to work so well in high school. But an even bigger surprise was when Doris Korda, Hawken’s program director, told me she was getting calls and emails from K-12 teachers across the country asking her to hold a “Hawken Lean LaunchPad for K-12 Educators” workshop.

So the Hawken teaching team took a deep breath and they offered this class – here at the K&S Ranch – so other educators could learn what Hawken is doing and how they’re doing it. Here’s what they were trying to accomplish.

If you can’t see the video click here

Thirty educators from 19 public and private schools throughout the U.S. attended their inaugural workshop.

These educators arrived at the ranch with a palpable sense of urgency, eager for the tools needed to build their own classes. There are no established Lean K-12 curricula, textbooks or handbooks for entrepreneurship programs. The class offered the first set of Lean educators’ materials anywhere. It took the attendees through the basics of Lean and how to build the class at their own schools.

The Hawken folks knew that in the back of the minds of other educators there was going to be the question, “Will this really work with my students? Can I really get them out of the classroom and expect real learning?” In what I thought was a stroke of genius, the Hawken team brought seven Hawken students who had taken the lean entrepreneurship class to help teach this educators course. These students told the attendees real world stories of how the class changed their lives and offered input and advice about what worked and didn’t for them.

The energy at the ranch was off the charts. Every minute was filled with talk about how to build this new model of learning and how to use LLP to encourage students to think creatively and analytically.

The attendees went back to their schools armed with a methodology and sample curriculum to develop their own entrepreneurship courses and put what they learned into practice. Some will take what they learned and apply Lean entrepreneurial principles to create innovate STEM programs and/or to encourage the growth of entrepreneurial ecosystems beyond school walls.

Here’s what some of them had to say about the experience:

If you can’t see the video click here

Jeremy Wickenheiser, a high school teacher with the Denver School of Science and Technology, a STEM public school serving 6,500 students, summed up the remarks we heard again and again: “This is the beginning of a movement to change how students learn.”

What’s Next

Encouraged by the attendees, Hawken is developing a comprehensive educational program for educators, with workshops on the East and West coasts, an educator’s handbook, and codified systems to help educators build their own experiential, LLP-based K-12 programs.

To learn about the workshops and sign up, click here.

Lessons Learned

The old ways of teaching entrepreneurship prepared students for small businesses

We needed a new educational approach to prepare them for scalable startups

Using the Lean LaunchPad, the Hawken School developed a successful entrepreneurship program for middle and high school students to do just that

Now they are teaching other educators how to do the same

Filed under: Lean LaunchPad, Teaching

September 16, 2014

How To Find the Right Co-Founders?

How do you figure out what’s the right mix of skills for the co-founders of your startup?

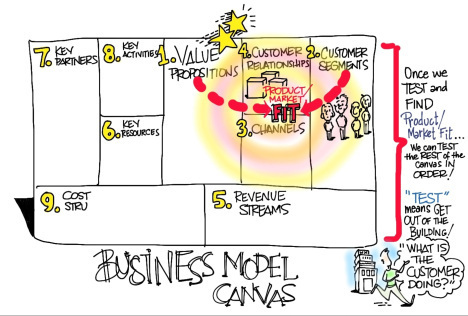

Surprisingly if you’ve filled out the business model canvas you already know who you need.

——-

I was having breakfast with Radhika, an ex-grad student of mine who wanted to share her Customer Discovery progress for her consumer hardware startup. She started by sketching her business model canvas on a napkin, but somehow the conversation quickly shifted to what was really on her mind. “After reading your post on Why Founders Should Know How to Code it looks like web/mobile startups have it easy. They seem to know the right mix of skills on their founding team is a hacker, hustler and designer. But what about for us, a consumer hardware hardware company? Trying to figure out what the right set of co-founders isn’t so clear. How do I decide who I need to have on board on day one? Who can I hire later? And what can I outsource?”

Co-founders Skills are the First Derivative of the Business Model Canvas

I told Radhika this is a perennial question for startups. I had struggled with this one for years. And over time every venture capitalist develops their own gut feel for what makes up a great team in their industry. I said, “If you’ve filled out the business model canvas you already know who you need on your founding team, the answer is staring us in the face.”

She looked at bit puzzled, so I continued to explain…

One of the virtues of using the Business Model Canvas as part of a Lean Startup is that it helps you frame each one of your nine critical hypotheses.

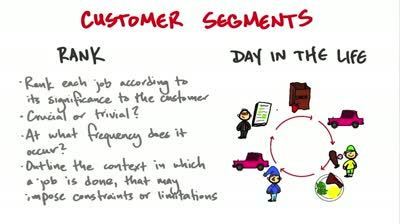

While most of the early attention in a startup is paid to finding product market fit (the match between value proposition and customer segment on the right-side of the canvas) it’s the left side of the canvas that will tell you what your founding team should look like.

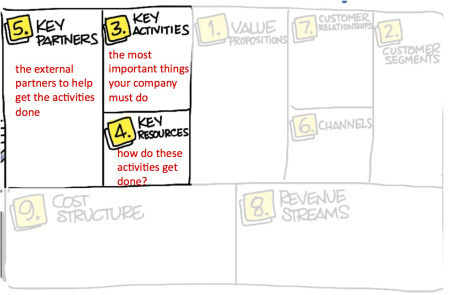

Understanding Activities and Resources Will Help You Spec Your Team

I suggested to Radhika that we start by looking at the canvas box labeled “key activities”. “Activities” is where you define the most important things your company must do to make the rest of your business model work. Activities define the unique expertise your company needs to deliver the value proposition, customers, channels, customer relationships and/or revenue. (If you’re a startup it’s easy to get confused on this step. We don’t need to know your activities for your five-year plan. Just list the Activities needed to get a major early milestone – i.e. cash flow positive, or first million users, regulatory submission/approval, etc.)

For example, if you’re building a mobile app, then the key activities are: app software development, user interface design and demand creation skills. Or if you’re building consumer electronics the key activities might be: low cost hardware design, high volume manufacturing, user interface design, consumer branding and retail distribution. For medical devices it might be mechanical engineering, clinical trials, regulatory approval, freedom to operate (intellectual property) and figuring out a reimbursement strategy.

So What Does this Have to Do With A Founding Team?

Once you establish what activities your company needs to do, the next question is, “how do these activities get accomplished?” i.e. what resources do I need to make the activities happen? The answer to that question is what goes in the “Resources” box on the canvas (and if third parties outside your company are going to provide it, in the Partners box.)

For example, in web and mobile apps most of the resources needed at first are people: a developer (the hacker), a user interface designer, and someone to lead the team and create customer demand and if needed raise capital (the hustler).

In medical device startups these resources are expertise in the basic science, industrial design, human factors, managing Contract Research Organizations, reimbursement, Intellectual Property, and someone to lead the team and raise capital and establish strategic partnerships. Therefore the ideal medical device team might be a physician; engineer; operator; business development/financial analyst.

Are We Missing A Founder?

Once you’ve figured out the activities and resources, you can then ask, “If these activities are crucial in building our company and these resources are the critical people skills need to make them happen. Does anyone on the founding team have these skills? Are we missing a founder? Or can we outsource these activities to Partners?”

Radhika nodded. “I get it” she said, “understanding activities and resources help me identify and then prioritize the skill sets I’ll need, but what about the individual characteristics of the individuals – resilience? tenacity? agility? team work? How much value should I put on co-founders I’ve worked with before?”

I smiled and said, “Figure out what you need first, then we can have another coffee.”

Lessons Learned

Figuring out the right founding team starts with listing the critical activities to make the startup successful in the first year or so

Next, what human resources are necessary to make those activities happen?

Can these skills be outsourced to partners or are they integral to the DNA of the company?

If they’re integral to the company’s success, they should be part of the founding team

Filed under: Customer Development

September 12, 2014

Why Translational Medicine Will Never be The Same

There have been 2 or 3 courses in my entire education that have changed

the way I think. This is one of those.

Hobart Harris Professor and Chief, Division of General Surgery at UCSF

For the past three years the National Science Foundation Innovation Corps has been teaching our nations best scientists how to build a Lean Startup. Close to 400 teams in robotics, computer science, materials science, geoscience, etc. have learned how to use business models, get out of the building to test their hypotheses and minimum viable product.

However, business models in the Life Sciences are a bit more complicated than those in software, web/mobile or hardware. Startups in the Life Sciences (therapeutics, diagnostics, devices, digital health, etc.) also have to understand the complexities of reimbursement, regulation, intellectual property and clinical trials.

Last fall we prototyped an I-Corps class for life sciences at UCSF with 25 teams. Hobart Harris led one of the teams.

What Hobart learned and how he learned it is why we’re about to launch the I-Corps @ NIH on Oct 6th.

If you can’t see the video click here

Translational medicine will never be the same.

Filed under: Lean LaunchPad, Life Sciences (NIH), NSF (National Science Foundation)

September 9, 2014

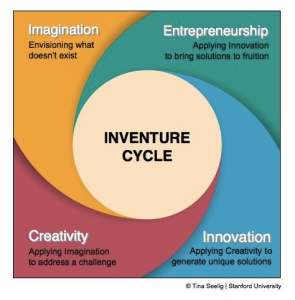

How To Think Like an Entrepreneur: the Inventure Cycle

The Lean Startup is a process for turning ideas into commercial ventures. Its premise is that startups begin with a series of untested hypotheses. They succeed by getting out of the building, testing those hypotheses and learning by iterating and refining minimal viable products in front of potential customers.

That’s all well and good if you already have an idea. But where do startup ideas come from? Where do inspiration, imagination and creativity come to bear? How does that all relate to innovation and entrepreneurship?

Quite honestly I never gave this much thought. As an entrepreneur my problem was that I had too many ideas. My imagination ran 24/7 and to me every problem was a challenge to solve and new product to create. It wasn’t until I started teaching that I realized that not everyone’s head worked the same way. While the Lean Startup gave us a process for turning ideas into businesses – what’s left unanswered was, “Where do the ideas come from? How do you get them?”

It troubled me that the practice of entrepreneurship (including the Lean Startup) was missing a set of tools to unleash my students’ imaginations and lacked a process to apply their creativity. I realized the innovation/entrepreneurship process needed a “foundation” – the skills and processes that kick-start an entrepreneurs imagination and creative juices. We needed to define the language and pieces that make up an “entrepreneurial mindset.”

As luck would have it, at Stanford I found myself teaching in the same department with Tina Seelig. Tina is Professor of the Practice at Stanford University School of Engineering, and Executive Director of the Stanford Technology Ventures Program. Reading her book inGenius: A Crash Course on Creativity was the first time I realized someone had cracked the code on how to turn imagination and creativity into innovation.

Here’s Tina’s latest thinking on the foundational skills necessary to build a new venture.

—-

There is an insatiable demand for innovation and entrepreneurship. These skills are required to help individuals and ventures thrive in a competitive and dynamic marketplace. However, many people don’t know where to start. There isn’t a well-charted course from inspiration to implementation.

Other fields — such as physics, biology, math, and music — have a huge advantage when it comes to teaching those topics. They have clearly defined terms and a taxonomy of relationships that provide a structured approach for mastering these skills. That’s exactly what we need in entrepreneurship. Without it, there’s dogged belief that these skills can’t be taught or learned.

Below is a proposal for definitions and relationships for the process of bringing ideas to life, which I call the Inventure Cycle. This model provides a scaffolding of skills, beginning with imagination, leading to a collective increase in entrepreneurial activity.

Inventure Cycle

Imagination is envisioning things that do not exist

Creativity is applying imagination to address a challenge

Innovation is applying creativity to generate unique solutions

Entrepreneurship is applying innovation, bringing ideas to fruition, by inspiring others’ imagination

This is a virtuous cycle: Entrepreneurs manifest their ideas by inspiring others’ imagination, including those who join the effort, fund the venture, and purchase the products. This model is relevant to startups and established firms, as well as innovators of all types where the realization of a new idea — whether a product, service, or work of art — results in a collective increase in imagination, creativity, and entrepreneurship.

This is a virtuous cycle: Entrepreneurs manifest their ideas by inspiring others’ imagination, including those who join the effort, fund the venture, and purchase the products. This model is relevant to startups and established firms, as well as innovators of all types where the realization of a new idea — whether a product, service, or work of art — results in a collective increase in imagination, creativity, and entrepreneurship.

This framework allows us to parse the pathway, describing the actions and attitudes required at each step along the way.

Imagination requires engagement and the ability to envision alternatives

Creativity requires motivation and experimentation to address challenges

Innovation requires focusing and reframing to generate unique solutions

Entrepreneurship requires persistence and the ability to inspire others

Not every person in an entrepreneurial venture needs to have every skill in the cycle. However, every venture needs to cover every base. Without imaginers who engage and envision, there aren’t compelling opportunities to address. Without creators who are motivated to experiment, routine problems don’t get solved. Without innovators who focus on challenging assumptions, there are no fresh ideas. And, without entrepreneurs who persistently inspire others, innovations sit on the shelf.

Let’s look at an example to see these principles at work:

As a Biodesign Innovation Fellow at Stanford University, Kate Rosenbluth spent months in the hospital shadowing neurologists and neurosurgeons in order to understand the biggest unmet needs of physicians and their patients.

In the imagination stage, Kate worked with a team of engineers and physicians to make lists of hundreds of problems that needed solving, from outpatient issues to surgical challenges. By being immersed in the hospital with a watchful eye, she was able to see opportunities for improvement that had been overlooked. This stage required engagement and envisioning.

In the creativity stage, the team was struck by how many people struggle with debilitating hand tremors that keep them from holding a coffee cup or buttoning a shirt. They learned that as many as six million people in the United States are stricken with Parkinson’s disease, and other conditions that cause tremors. The most effective treatment is deep brain stimulation, an onerous and expensive intervention that requires permanently implanting wires in the brain and a battery pack in the chest wall. Alternatively, patients can take drugs that often have disabling side effects. The team was driven to help these patients and began meeting with experts, combing the literature, and testing alternative treatments. This stage required motivation and experimentation.

In the innovation stage, Kate had an insight that changed the way that she thought about treating tremors. She challenged the assumption that the treatment had to focus on the root cause in the brain and instead focused on the peripheral nervous system in the hand, where the symptoms occur. She partnered with Stanford professor Scott Delp to develop and test a relatively inexpensive, noninvasive, and effective treatment. This stage required focus and reframing.

In the entrepreneurship stage, Kate recently launched a company, Cala Health, to develop and deliver new treatments for tremors. There will be innumerable challenges along the way to bringing the products to market, including hiring a team, getting FDA approval, raising subsequent rounds of funding, and manufacturing and marketing the device. These tasks require persistence inspiring others.

While developing the first product, Kate has had additional insights, which have stimulated new ideas for treating other diseases with a similar approach, coming full circle to imagination!

The Inventure Cycle is the foundation of frameworks for innovation and entrepreneurship, such as design thinking and the lean startup methodology. Both of these focus on defining problems, generating solutions, building prototypes, and iterating on the ideas based on feedback. The Inventure Cycle describes foundational skills that are mandatory for those methods to work. Just as we must master arithmetic before we dive into algebra or calculus, it behooves us to develop an entrepreneurial mindset and methodology before we design products and launch ventures. By understanding the Inventure Cycle and honing the necessary skills, we identify more opportunities, challenge more assumptions, generate unique solutions, and bring more ideas to fruition.

With clear definitions and a taxonomy that illustrates their relationships, the Inventure Cycle defines the pathway from inspiration to implementation. This framework captures the skills, attitudes, and actions that are necessary to foster innovation and to bring breakthrough ideas to the world.

Lessons Learned

The Inventure Cycle defines entrepreneurship as applied innovation, innovation as applied creativity, and creativity as applied imagination

Entrepreneurship requires inspiring others’ imagination, resulting in a collective increase in creativity, innovation, and entrepreneurship

This framework allows us to parse the skills, attitudes, and actions needed at each step in the entrepreneurial process.

Filed under: Customer Development, Teaching, Technology

September 3, 2014

Why Founders Should Know How to Code

“By knowing things that exist, you can know that which does not exist.”

Book of Five Rings

A startup is not just about the idea, it’s about testing and then implementing the idea.

A founding team without these skills is likely dead on arrival.

—-

I was driving home from the BIO conference in San Diego last month and had lots of time for a phone call with Dave, an ex student and now a founder who wanted to update me on his Customer Discovery progress. Dave was building a mobile app for matching college students who needed to move within a local area with potential local movers. He described his idea like “Uber for moving” and while he thought he was making real progress, he needed some advice.

Customer Discovery

As the farm fields flew by on the interstate I listened as Dave described how he translated his vision into a series of hypotheses and mapped them onto a business model canvas. He believed that local moves could be solved cheaply and efficiently through local social connections. He described when he got out of the building and quickly realized he had two customer segments – the students – who were looking for low budget, local moves and the potential movers – existing moving companies, students and others looking to make additional income. He worked hard to deeply understand the customer problems of these two customer segments.  After a few months he learned how potential customers were solving the local moving problem today (do it themselves, friends, etc.) He even learned a few things that were unexpected – students that live off campus and move to different apartments year-to-year needed to store their furniture over the summer breaks, and that providing local furniture storage over the summer was another part of his value proposition to both students and movers.

After a few months he learned how potential customers were solving the local moving problem today (do it themselves, friends, etc.) He even learned a few things that were unexpected – students that live off campus and move to different apartments year-to-year needed to store their furniture over the summer breaks, and that providing local furniture storage over the summer was another part of his value proposition to both students and movers.

As he was learning from potential customers and providers he would ask, “What if we could have an app that allowed you to schedule low cost moves?” And when he’d get a positive response he’d show them his first minimal viable product – the mockup he had created of the User Interface in PowerPoint.

This was a great call. Dave was doing everything right. Until he said, “I just have one tiny problem.” Uh oh…

“I organized some moves by manually connecting students with the movers. And I even helped on some of the moves myself. But I’m having a hard time getting to my next minimal viable product. While I have all this great feedback on my visual mockups I can’t iterate my product. My contract developers building the app aren’t very responsive. It takes weeks to make even a simple change.”

I almost rear-ended another car when I heard this. I said, “Help me understand.. neither you nor your cofounder can code and you’re building a mobile app? And you’ve been at this for six months??” Whoah. This startup was broken at multiple levels. In fact, it wasn’t even a startup.

The Problem

Dave sounded confused. “I thought building a company was all about having hypotheses and getting out of the building and testing them?’

There were three problems with Dave’s startup.

He was confusing having an idea with the ability to actually build and implement the idea

He was using 3rd parties to build his app but he had no expertise on how to manage external developers

His inability to attract a co-founder who could code was a troubling sign

A Startup is Not Just About a Good Idea

As the miles sped by I explained to Dave that he had understood only two of the three parts of what makes a Lean Startup successful. While he correctly understood how to frame his hypotheses with a business model canvas, and he was doing a good job in customer development – the third component of Lean is using Agile Development to rapidly and iteratively build incrementally better versions of the product – in the form of minimal viable products (MVP’s).

The emphasis on the rapid development and iteration of MVP’s is to speed up how fast you can learn; from customers, partners, network scale, adoption, etc. Speed keeps cash burn rate down while allowing you to converge on a repeatable and scalable business model. In a startup building MVP’s is what turns theory into practice.

Dave had fallen into the new founder trap of looking at the business model canvas and thinking that coding was simply an activity (rapidly build mockups of first the the U/I and then the app). And that he could identify the resources needed, (outsourced contract developers who could build it for him) and he would hire a partner to do so. All great in theory but simply wrong. In a web/mobile startup coding is not an outsourced activity. It’s an integral part of the company’s DNA.

Having a coder as part of the founding team is essential.

Coding is the DNA of a Web/Mobile Startup

I offered that if Dave wanted to be the founding CEO then he was going to have to do two things: first, create a reality distortion field large enough to attract a technical co-founder. And second, learn how to code.

Dave was a bit embarrassed when he explained, “I’ve been trying to attract another co-founder who could code but somehow couldn’t convince anyone.” (This by itself should have been a red flag to Dave.) And then he continued, “But why should I have to know how to code, I’m not going to write the final app.”

One interesting thing about the Lean Startup is that it teaches founders about Sales and Marketing (and a bit of finance) without making them get an MBA or a decade of sales experience. Founders who go through the process will have an appreciation of the role of sales and marketing like no textbook or classroom could provide. Having done the job themselves, they’ll never be at the mercy of a domain expert. The same is true for coding.

I was glad I had a lot of time in the car, because I was able to explain my belief that all founders in a web or mobile startup need to learn how to code. Not to become developers but at a minimum to appreciate how to hire and manage technical resources and if possible to deliver the next level of MVP’s themselves.

Dave’s objection was to list a few successful startups that he knew where that wasn’t the case. I pointed out that are always “corner cases” and if he thought I was wrong he could simply ignore my advice.

As I was about to pull off an exit for lunch and to recharge my car I strongly suggested to Dave that for both this startup and the rest of career he put his startup on hold and invest his time in attending a coding bootcamp. It would take him to the first step in appreciating the issues in managing web development projects, identifying good developers, and finding a technical co-founder.

Weeks later Dave dropped me a note, “Boy, what I didn’t know about how much I didn’t know. Thanks!”

Lessons Learned

Startups are not just about the idea, they’re about testing and implementing the idea

A founding web/mobile team without a coder past the initial stages of Customer Discovery is not a startup

Everyone on the founding team ought to invest the time in a coding bootcamp

Your odds of building a successful startup will increase

Filed under: Customer Development, Technology

August 7, 2014

What Do Customers Get From You? 2 Minutes to Find Out

August 5, 2014

Pioneering Women in Venture Capital: Kathryn Gould

I met Kathryn Gould longer ago than either of us want to admit. Kathryn has been the founding VP of Marketing of Oracle, a successful recruiter, a world class Venture Capitalist, a co-founder of a Venture Capital firm, a great board member, one of my mentors and most importantly a wonderful friend. During her career she made a big point of not telling you: she was one of the first women Venture Capitalist’s in Silicon Valley (along with M.J. Elmore and Ann Winblad) – “I’m just a VC.” Or one of the first women co-founders of a VC firm – “I co-founded a great firm.” She was twice as smart and just as tough as the guys. She has been a mentor and role model not just for a generation of women VC’s and CEO’s but for all VC’s and CEO’s – and I’m honored to have been one of them.

One of the reasons I took up teaching is my strong belief that it’s incumbent on all of us to make those who come after us smarter than we were.” So when I heard Kathryn gave the University of Chicago commencement speech I suggested that she reach out to a larger audience and share her decades of experience.

Her response? “The last thing I want is a bunch of people bugging me while I’m growing my grapes, flying, painting, playing music, and generally goofing off.” I pointed out that, “Now that you retired, what happens to all the knowledge and experience you’ve acquired?” She still demurred so I gave it one last shot. I sent her an email saying, “When you’re gone everything you learned goes with you. This really is bigger than you. I have two daughters starting careers and nothing could be more inspiring than hearing your story. You really ought to share your journey.”

So for the first time ever, she has. Here’s Kathryn’s story.

——-

Why Give a Commencement speech

One of the more fun things I’ve been asked to do lately was give the commencement speech at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business in June 2014. What I didn’t tell them before, during, or after the talk was that I’d never gone to my own University of Chicago MBA graduation, nor had I gone to my BSc in physics graduation at University of Toronto. I’ve never been big on pomp, and I had fun jobs I wanted to go to right away after each of them. And to be fair, I wasn’t summa cum laude in either case. I was merely respectable, so there was no appealing ego trip involved. Anyway it was high time I went to a graduation.

The most personally interesting part of writing this speech was thinking about what I could say to the young women that I wish I’d heard at their age. (I heard nothing).

So, for the first time, I thought hard about what it was like to be a woman in a man’s business. Not thinking about it earlier was a survival strategy—because if I’d thought about it, I’d have wanted to TALK about it, and that would have been stupid. I was working and competing with men daily. And successfully. And the truth is, I like working with men. Being a physicist-turned-engineer, I have very little experience working with anything but men. So when members of the press or militant feminist types would question me about this stuff, I would avoid and be annoyed. Now that I’m retired I can speak out and let the chips fall. Still, a nod to Sheryl Sandberg for saying her piece while in the thick of it.

In the aftermath of the speech, I got the most resonance in two areas:

1) make unconventional choices that fit YOUR OWN aspirations

2) from women appreciating the advice to go around obstacles, and enjoying hearing from a fellow ‘dragon lady’

Actually it wasn’t “dragon lady,” it was a stronger, less feminine term — “Ball Buster” — but, hey, I couldn’t say that in a speech. Reason I know is that I’m still very close to most of the former CEOs from my boards. I ran this speech by a couple of them. Over time they had heard me referred to as that other term. They would jump to my defense – and they report that the people who said this had never met me –it was just the “word on the street.” Insidious, yes?

Anyway, mine is a study in making unconventional career choices (not that I recommend everybody go be a recruiter for a few years!), and searching for what you’re great at, and meant to encourage women to go right through those walls.

So they call you a “dragon lady”; so what?!

Here’s the speech:

2014 University of Chicago Commencement speech ‘Your Great Adventure’

“I’m so happy to be here today: First, to help you celebrate your success thus far, and more important: to celebrate your last day of doing what is expected of you —now each of you embark on your own great adventure—there is no ‘expected’ path from here on. You get to create your own history. No more tests, get into this school, get into that class, get this degree—now the real adventure begins. The second reason I’m glad to be here today is that 2 years ago, when Dean Kumar first asked me to do this speech, I wasn’t sure I”d even be alive, so I had to pass. More on that later.

So, about your adventure: should you have a plan? Maybe. But don’t follow it. Planning prepares the mind, and chance favors the prepared mind, but chance usually messes up plans! When I was where you are, 36 years ago (can ya believe it) I didn’t have a plan—but I did have an aspiration: I wanted to go to Silicon Valley and I wanted to work in startups. I had no idea how I was going to get from here to there. I was completely unprepared! We had literally one entrepreneurship course here in the mid 70s—taught by a guy who commuted in from Silicon Valley. Compare that to now—with our superb entrepreneurship curriculum, and I understand 70% of this class has either an interest or focus in entrepreneurship.

Chance Favors the Prepared Mind

So here’s how it happened for me. I had had a love affair with computers since I was 18 and a freshman physics major.

Computers were so different from now—arcane, annoyingly difficult— and interesting. But they weren’t really in Silicon Valley at the time—they were in Boston, Minneapolis, New York. So going to Silicon Valley wasn’t an obvious move at the time. It was the invention of the microprocessor that made it obvious for me. I quit my good job here and moved to the valley. Most people thought I was nuts. I had no idea what I was doing—just that I had to be there, and in a startup—so I took a job with the smallest company that made me an offer (passing up Intel, Tandem and Apple). It wasn’t a great choice, but I was THERE. But then, one our customers was Larry Ellison, with this little company that wasn’t even called Oracle at the time. I loved what he was working on (thanks to perspective in data management from my large company experience here—that prepared mind thing). So I joined Oracle when it was about 20 people, eventually becoming VP Marketing. And it was an amazing time. Larry was the best entrepreneur I’ve ever known, and completely unconventional…

What can you learn from this story so far?:

Put yourself in the way of success—get in front of an important wave and ride it.

Gravitate to what’s new.

Don’t be afraid to take a step down (Oracle was a $1 Million business, I had been marketing manager for a $100 Million business).

Build Your Skills Not Your Resume

Eventually I left Oracle, wanting to do another startup. Problem is, startups that have world changing potential are not that easy to find. I wanted another Oracle, not any old startup. So I did something completely crazy and unplanned—which looks brilliant only in hindsight! I noticed that I loved looking for a job, even tho I didn’t’ find a company I wanted to join. I liked meeting people, hearing the company plans, learning about their technology, figuring out if it was for real—all that was fun. How could I do that for a living? The answer of course, was Venture Capital, but that was not in the cards—as yet. I had met a few exec recruiters in the process and thought what they did was similar and interesting. So I started an exec search firm as a creative way to look for a new startup. Turns out that I quickly became one of the few best recruiters in the valley for CEO and VP levels, got to work with the best VCs and their startups. And who would have guessed—perfect preparation for the VC business. I ended up doing that for 5 years, and in the process saw about 80 startups in various stages of success and disarray. I developed a deadly accurate intuition on people, an unbeatable set of contacts, and loved working for myself in my little firm. By the 4th year, VCs were asking me to join them, partly for recruiting help, but more because I kept introducing them to startup investment opportunities. As you’ve heard, it’s excruciatingly hard to get in to the VC business, and there I was. Because I”d built some unique skills.

Plus, I had learned some stuff that you don’t get in business school:

How to cold call –adrenaline, real time, 3 seconds to grab their attention—learn this!

Also the adage As hire As, Bs hire Cs—absolutely true—be careful of the company you keep,

And what goes around comes around. Help people with their careers, their ideas, contacts—and I’m serious, good things come back years later.

I also learned that the first time without a paycheck is a little scary.

Find Your Obession

I joined VC firm Merrill Pickard in 1989. My first IPO wasn’t until 1995—the VC business takes patience. Two companies I helped start in 1992, DCTM and Grand Junction Networks both became Stanford business school cases and very valuable, successful companies. I was on the way to my lifetime IRR of 90%. I loved the business, and I was good at it. But then, trouble. My two best partners went off to start Benchmark Capital, very successful to this day, so my firm was going to blow up. I went Boogie Boarding where I do my best thinking. I thought, gee, I could already afford to ride waves the rest of my life. That might be neat. But I couldn’t do it. I loved the business, couldn’t stop. So I started Foundation Capital in 1995. I loved starting my own firm, doing it my way. We brought in all operating guys—all had done startups, all had technical backgrounds. In 5 years we were one of the top firms in the Valley by any measure. I had found my obsession.

It’s Not the Calls You Take, It’s the Calls You Make One of my sayings

You are the creator of your destiny. In whatever business you’re in, there is always so much coming at you that you can stay insanely busy just responding. Don’t do that. Always think about what is your agenda, what do you want to make happen, what do you want the future to look like. This is not so easy.

Go Where the Action Is: It’s not over in the Valley

Now 35 years later, should you still move to the Valley (or Hollywood, or London, or Chicago!—or wherever the action is in your area of interest?). I can’t speak to the other places, but I”ll tell you what, it’s not over in the Valley. From electric cars to drones, DNA sequencing to robotic surgery, enterprise software to social media –the size and variety of these markets makes the Valley of my early days look bush league. There’s no end in sight. The valley startup culture and talent pool is unique in the world. If you think maybe you should go there—maybe you should.

I retired in 2006. My husband and I bought a vineyard—so I’m a beginner again! With another startup!

A Word to the Ladies Here

I understand a third of the class is women. I have always said, with an annoyed attitude when people ask, that there are no obstacles to women these days, just look at me! That’s the safe way to answer, right? But it’s not entirely true. One of the gifts of talking to you ladies here is that I forced myself to reflect on this. I’ll just mention two obstacles that hit me—neither of which I even reacted to at the time, just accepted.

First Obstacle

I wanted to go to Caltech, but they didn’t take women undergrads until 1970. I wasn’t mad about that; I just thought it was my fault for being interested in guy things. So I dated a Caltech student and got to use their computer—first computer I ever met too—a monster. Structural obstacles like this are over with for you. Good riddance.

Second Obstacle

Remember that business of starting Foundation Capital when my first firm blew up? I did it because I didn’t have a choice—couldn’t get a job. Really. I spent a couple of months talking with the few VC firms that I was willing to join. (yes, I was picky) It became clear it was going to take a long time to get into one, and I didn’t have a long time. I didn’t want to lose my momentum. Mind you, I was one of the top handful of VCs in the business at the time. Not on the Midas list yet, because it hadn’t been invented, but anybody could see that my results were heading toward extraordinary. I have to think that a guy with my numbers would have been snapped up pretty fast. For me, starting the firm and raising the money was way faster. Don’t you think that’s stunning? A pretty big fat obstacle. So we went from Boogie Board to money in the bank in 6 months. Not that I’m sorry—it turned out great. But you ambitious women will surely face something like this in your career. Just go around it! There is always a way. Note on the VC business, only 4% of senior VCs are women, according to Fortune Magazine. I don’t think it’s changing anytime soon either.

Now to be fair, consider your advantages: you’re much more memorable than most of the guys, they won’t forget you, and there is a self selection: the men who have the guts to do business with you have the extra self confidence to be more successful. The guys that wanted me on their board of directors had moxy—because of course they had heard all the crap about how I was a dragon lady (all ambitious women get called that as you know) and they still went for it. Who knows—could be why my companies were so successful…

I often walk among my grapevines and think how grateful I am for my life right now. But if the vines had come first, without the adventure and hard work, it wouldn’t be nearly as sweet. So that’s my story so far—but it’s not over yet, because the cabernet is really good!

Tending a New Crop in My Next Venture

So now, for each of you, go create your own unique adventure. You are done preparing—go do it! Make a plan, but don’t stick to it. Let chance favor your prepared mind. Break rules, find your obsession, be extraordinary!”

View the speech in its entirety here

Filed under: Commencement Speeches, Teaching, Venture Capital

July 30, 2014

Driving Corporate Innovation: Design Thinking vs. Customer Development

Startups are not smaller versions of large companies, but interestingly we see that companies are not larger versions of startups.

I’ve been spending some time with large companies that are interested in using Lean methods. One of the conundrums is why does innovation take so long to happen in corporations? Previously Hank Chesbrough and I have written about some of the strategic issues that impede innovation inside large corporations here and here.

Two methods, Design Thinking and Customer Development (the core of the Lean Startup) provide the tactical day-to-day process of how to turn ideas into products.

While they both emphasize getting out of the building and taking to customers, they’re not the same. Here’s why.

—–

Urgency Drives Innovation Speed

Startups operate quickly – at a speed driven by the urgency of a proverbial gun-to-their-head called “burn rate.” Any founding CEO can tell you three numbers they live and breathe by:

the amount of cash left in the bank

their burn rate (the amount of money they’re spending monthly minus any revenue coming in) and

the day they run out of money and have to shut the doors (or get a new round of funding.)

If you’re a founder, there’s a constant gnawing fear in the pit of your stomach that it will all end badly; running out of money, having to fire all your employees and failing publicly. (Whoever says, “Failure feels OK in startups has clearly never run a startup.)

A startup CEO adroitly translates this urgency to their employees not with reminders of “we’ll all soon be out of jobs,” but with a bias to action – making measureable progress in getting minimum viable products in front of customers, beating competitors, getting users/customer quickly, and generating revenue. Startups build a culture of commitment and drive to make things happen.

In large companies, the employees are no less smart, but the organization is optimized to deliver repeatable products, revenue and profits. To support this, its corporate culture is dominated by process, procedures and incentives. In large companies, even the most innovative projects (whether it’s process innovation, continuous innovation or disruptive innovation) are not going to make or break the company – and employees know it. Canceling a project may frustrate the team members working on it but unlike in a startup, they still have their jobs, offices and houses and the company won’t close. Attempts to instill urgency via a gun-to-the-head philosophy are frowned on by Corporate HR. All of this adds up to a “complacency culture” rather than an “urgency culture.”

Customer Development versus Design Thinking

This real sense of urgency—and how it shapes employee attitudes and practices – is a big reason why innovation processes in startups are different from those in large companies. One of these processes is how startups versus companies learn from customers. It’s the difference between Customer Development versus Design Thinking.

Customer Development and Design Thinking share similar characteristics in exploring customer needs, but their origins, differences and speed in practice are very different.

I invented the Customer Development process trying to solve two startup problems. First, most Silicon Valley startups were (and primarily still are) technology-driven. They are founded and funded by visionaries who already have products (or product ideas based on technology innovation) and now need to find customers and markets. (Think of the early days of Intel, Apple, Cisco, Google, Facebook, Twitter, etc.) Second, burn rate and dwindling cash meant startups had to find these customers and the attendant product/market fit rapidly – before they ran out of money. These two characteristics– a technology-driven product already in hand and a need for speed– drove the unique characteristics of Customer Development. These include:

Moving with speed, speed and did I say speed?

Starting with a series of core hypotheses – what the product is, what problem the product solves, and who will use/pay for it

Finding “product/market fit” where the first variable is the customer, not the product

Pursuing potential customers outside the building to test your hypotheses

Trading off certainty for speed and tempo using “Good enough decision making“

Rapidly building minimum viable products for learning

Assuming your hypotheses will be wrong so be ready for rapid iterations and pivots

Design Thinking also focuses on understanding the needs of potential customers outside the building. But its motivations and tactics are different from those of Customer Development. Design Thinking doesn’t start with a founder’s vision and a product in-hand. Instead it starts with “needs finding” and attempts to reduce new product risk by accelerating learning through rapid prototyping. This cycle of Inspiration, Ideation and Implementation is a solutions-based approach to solving customer problems.

Design Thinking is perfectly suited to situations where the process isn’t engineering-driven; time and money are abundant and the cost (and time) of a failure of a major project launch can be substantial. This process makes sense in a large company when the bets on a new product require large investments in engineering, a new factory or spending 10s or 100s of millions on launching a new product line.

But therein lies the conundrum. Because of the size of the dollars at stake (and your career), lots of effort is spent to make sure your understanding of the customer and the product is right. At times large companies will drag out these design-thinking investigations (prototype after prototype) for years. Often there is no place where urgency gets built into the corporate process. (Just to be clear this isn’t a failure of the process. Urgency can be built in, it’s just that most of the time it’s not.)

Both Models Work for Large Companies

There is no right process for all types of corporate innovation. In a perfect world you wouldn’t need Customer Development. No corporate R&D would happen before you understood customer problems and needs. But until that day, the challenge for executives in charge of corporate innovation is to understand the distinction between the two approaches and decide which process best fits which situation. While both get product teams out of the building the differences are in speed, urgency and whether the process is driven by product vision or customer needs.

In one example, you might have a great technology innovation from corporate or division R&D in search of customers. In another, you might have a limited time to respond to rapidly shifting market or changing competitive environment. And in still another, understanding untapped customer needs can offer an opportunity for new innovation.

Often I hear spirited defenses for Customer Development versus Design Thinking or vice versa, and my reaction is to slowly back out of these faith-based conversations. For large companies, it isn’t about which process is right – the reality is that we probably haven’t invented the right process yet. It’s about whether your company is satisfied with the speed, quality and size of the innovations being produced. And whether you’re applying the right customer discovery process to the right situation. No one size fits all.

There’s ample evidence from the National Science Foundation that Customer Development is the right process for commercializing existing technology. There’s equally compelling evidence from IDEO the Stanford D-School and the Biodesign Innovation Process that Design Thinking works great in finding customer needs and building products to match them.

Lessons Learned

Customer Development and Design Thinking are both customer discovery processes

Customer Development starts with, “I have a technology/product, now who do I sell it to?”

Design Thinking starts with, “I need to understand customer needs and iterate prototypes until I find a technology and product that satisfies this need”

Customer Development is optimized for speed and “good enough” decision making with limited time and resources

Design Thinking is optimized for getting it right before we make big bets

Filed under: Big Companies versus Startups: Durant versus Sloan

July 28, 2014

Not All Startups Are the Same. 2 Minutes to Find Out Why

If you can’t see the video click here

Subscribe for more videos than you can ever watch here

Filed under: 2 Minute Lessons, Market Types

Steve Blank's Blog

- Steve Blank's profile

- 381 followers