Steve Blank's Blog, page 29

December 15, 2015

Blank’s Rule – To predict the future 1/3 of you need to be crazy

In a rapidly changing world those who copy the past have doomed their future.

When companies or agencies search for disruptive and innovative strategies they often assemble a panel of experts to advise them. Ironically the panel is often made up of people whose ideas about innovation were relevant in the past.

I’ve seen this scenario play out in almost every large company and government agency trying to grapple with disruption and innovation. They gather up all the “brand-name wisdom” in an advisory board, task force, panel, study group, etc. All of these people – insiders and outsiders – have great resumes, fancy titles, and in the past brilliant insights. But unintentionally, by gathering the innovators from the past, the past is what’s being asked for – while it’s the future that’s needed.

You can’t create a blueprint for the future. But we know one thing for sure. The future will be different from the past. A better approach is to look for people who are the contrarians, whose ideas, while they sound crazy, are focused on the future. Most often these are not the safe brand names.

If your gathered advisory board, task force, panel, study group, etc., tasked with predicting the future doesn’t have 1/3 contrarians, all you’re going to do is predict the past.

——-

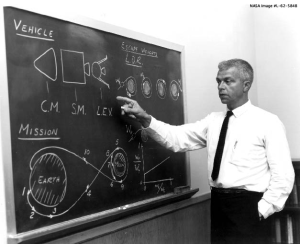

In the 1950’s and 60’s with the U.S and the Soviet Union engaged in a full-blown propaganda war, the race to put men in space was a race for prestige – and a proxy for the superiority of one system of government over the other.

In 1961 the U.S. was losing the “space race.” The Soviets had just put a man in orbit and their larger rockets allowed them to launch larger payloads and perform more space spectaculars than the U.S. The new President, John Kennedy looked for a goal where the U.S. could beat the Soviet Union. He decided to raise the stakes by declaring that we would land a man on the moon “before the decade is out” (brave talk before we even got someone into orbit.) This meant that NASA had to move quickly to find the best method to accomplish the journey.

NASA had panels of experts arguing about which of two options to use to get to the moon: first they considered, direct ascent; then moved to another idea, Earth-orbit rendezvous (EOR).

Direct ascent was basically the method that had been pictured in science fiction novels and Hollywood movies for a decade.  A giant rocket would be launched directly to the moon, land and then blast off for home. But there were three problems:

A giant rocket would be launched directly to the moon, land and then blast off for home. But there were three problems:

direct ascent was the least efficient way to get to the moon and would require a giant rocket (the Nova) and

the part that landed on the moon would be 65 feet tall (requiring one heck of a ladder to the surface of the moon.)

it wasn’t clear that a rocket this big could be ready by the end of the decade.

So NASA settled on the second option: Earth-orbit rendezvous. Instead of launching a whole rocket to the moon directly, Earth-orbit rendezvous would to launch two pieces of the spacecraft – one at a time – using Saturn rockets that were then in development. These pieces would meet up in earth orbit and send a ship, (still 65 feet tall as in the direct flight mode), to the moon and back to Earth. This idea was also a decade old – it was how they proposed building a space station. The advantage of Earth-orbit rendezvous to go to the moon was that it required a pair of less powerful Saturn rockets that were already under development.

If you can’t see the movie click here

All the smartest people at NASA (Wernher Von Braun, Max Faget,) were in favor of Earth-orbit rendezvous and they convinced NASA leadership this was the way to go.

But one tenacious NASA engineer, John Houbolt believed that we wouldn’t get to the moon by the end of the decade and maybe not at all if we went with Earth-orbit rendezvous.

Houbolt was pushing a truly crazy idea, Lunar-orbit rendezvous (LOR). This plan would launch two spaceships into Earth orbit on top of a single Saturn rocket. Once in Earth orbit, the rocket would fire again, boosting both spacecraft to the moon. Reaching orbit around the moon, two of the crew members would climb into a separate landing ship they carried with them – the lunar excursion module (LEM). The LEM would detach from the mother ship (called the command module), and land on the moon. The third crew member would remain alone orbiting the moon in the command module. When the two astronauts were done exploring the moon they would take off using the top half of the LEM, and re-dock with the command module (leaving the landing stage of the LEM on the moon.) The three astronauts in their command ship would head for home.

The third crew member would remain alone orbiting the moon in the command module. When the two astronauts were done exploring the moon they would take off using the top half of the LEM, and re-dock with the command module (leaving the landing stage of the LEM on the moon.) The three astronauts in their command ship would head for home.

The benefits of Lunar-orbit rendezvous (LOR) were inescapable.

You’d only need one rocket, already under development, to get to the moon

The part that landed on the moon would only be 14′ tall. Getting down to the surface was easy

Yet in 1961 LOR was a completely insane idea. We hadn’t even put a man into orbit, let alone figured out how to rendezvous and dock in earth orbit and some crazy guy was suggesting we do this around the moon. If it didn’t succeed the astronauts might die orbiting the moon. However, Houbolt wasn’t some crank, he was a member of the Lunar Mission Steering Group studying space rendezvous. Since he was only a mid-level manager he presented his findings to the internal task forces and the experts dismissed this idea the first time they heard it. Then they dismissed it the 2nd, 5th and 20th time.

Houbolt bet his job, went around five levels of NASA management and sent a letter to deputy director of NASA arguing that by insisting on ground rules to only consider direct ascent or earth orbit rendezvous meant that NASA shut down any out-of-box thinking about how to best get to the moon.

Luckily Houbolt got to make his case, and when Wernher Von Braun changed his mind and endorsed this truly insane idea, the rest of NASA followed.

We landed on the moon on July 20th 1969.

——-

I recently got to watch just such a panel. It was an awesome list of people. Their accomplishments were legendary, heck, every one of them was legendary. They told great stories, had changed industries, invented new innovation platforms, had advised presidents, had won wars, etc. But almost none of them had a new idea about innovation in a decade. Their recommendations were ones you could have written five years ago.

In a static world that would be just fine. But in a corporate world of continuous disruption and in a national security world of continuously evolving asymmetric threats you need to have crazy people being heard.

Or you’ll never get to the moon.

Lessons Learned

Most companies and agencies have their own John Houbolts. But most never get heard. Therefore, “Blank’s rules for an innovation task force”:

1/3 insiders who know the processes and politics

half of those who would provide top cover to non-standard solutions

1/3 outsiders who represent “brand-name wisdom”

They provide cover and historical context

1/6 crazy insiders – the rebels at work

They’ve been trying to be heard

Poll senior and mid-level managers and have them nominate their most innovative/creative rebels

(Be sure they read this before they come to the meeting.)

1/6 crazy outsiders

They’ve had new, unique insights in the last two years

They’re in sync with the crazy insiders and can provide outsiders with “cover”

Filed under: Corporate Innovation, Science and Industrial Policy

December 10, 2015

Entrepreneurs are Everywhere Show No. 13: Liz Powers and Rocio Perez-Ochoa

Successful founders believe anything is possible but they build strong founding teams to achieve their startup dreams.

Naivete and a shared vision are among the key markers for success, two social entrepreneurs said on the latest episode of Entrepreneurs are Everywhere, my radio show on SiriusXM Channel 111.

Liz Powers

Joining me at the Lean Startup Conference in San Francisco were:

Liz Powers, co-founder of ArtLifting, a for-profit online art gallery that features the work of homeless and disabled artists

Rocio Perez-Ochoa, co-founder of Bidhaa Sasa, which finances and distributes household goods that can improve families’ quality of life in rural Kenya

Rocio Perez-Ochoa

Listen to the full interviews by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here. (And download any of the past shows here.)

Clips from their interviews are below, but first a word about the show:

Entrepreneurs are Everywhere airs Thursdays at 1 pm Pacific, 4 pm Eastern on Sirius XM Channel 111. It follows the entrepreneurial journeys of founders sharing their experiences of what it takes to build a startup – from restaurants to rocket scientists, to online gifts to online groceries to entrepreneurial education and more.

The program examines the DNA of entrepreneurs: what makes them tick, how they came up with their ideas; and explores the habits that make them successful, and the highs, lows and pivots that pushed them forward.

Liz Powers is a social entrepreneur with a passion for helping homeless people. The Harvard graduate has received multiple awards and grants for her work. She started ArtLifting with her brother, Spencer, in 2013, and acknowledges her youth and enthusiasm have been assets.

Being naive is good. … If people knew all the challenges that were ahead of them, any rational person wouldn’t do it.

Steve : I always say you’re too young to know it can’t be done.

Liz : Exactly. A lot of times people would give me a ton of push back and say I was insane when we were starting ArtLifting. … Ignoring those negatives around you and figuring out who are the most strategic partners to be able to scale that impact.

… If we had really thought through ArtLifting beforehand then we wouldn’t have launched three months after the idea stage. We went for it. We just started a beta (test) with four artists, and super basic website template. A week later we had $10,000 in sales. It’s the same concepts as Lean Startup as get your idea out there as soon as possible and then pivot with customer reaction.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Rocio Perez-Ochoa is a former hedge fund manager who also was climate change policy advisor in the UK. Her first startup experience involved managing the financial arm of BBOXX, a manufacturer and distributor of solar home systems in the UK and Africa.

Early on in her journey to build Bidhaa Sasa, she discovered the importance of having a strong founding team.

The willingness to listen is something that I found is not very common. The willingness to experiment, get your hands dirty. You do it yourself, acquire … that philosophy. As a founder, you have to do it yourself. Otherwise, you never get firsthand information and just stick to your guns.

(Building a founding team) is really difficult. … We were three at the beginning. For one of them, it didn’t work.

Steve : Most of our listeners should understand that at least a third of startups never even get to start, because they melt down because of founding issues. In this case, you didn’t melt down, but you lost one-third of your founding team.

Rocio : Totally. In the first few months, it was clear for one of them, it didn’t work.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

—

Liz is a world-class sailor, the first woman in US sailing history to win the Intercollegiate Sailing Association’s National Sportsmanship Award. She draws parallels between sailing and doing a startup:

A lot of times the thought of sailing is like sitting on a yacht drinking wine and eating cheese. (But) I was in dingy sailing, boats that flip over all the time. We did a lot of weight lifting to prepare for nationals and prepare for top competition. I think that relates a lot to entrepreneurship because … you get right back up, but also with waking up early to do weight lifting in February, you know that this is for a competition six months down the line but you keep pushing to get yourself to that point.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Here’s how she got the idea for ArtLifting:

I felt a little guilty because I won this grant to start up art groups (to connect homeless women) because there weren’t any in Cambridge, in shelters, but (then) realized, well, just across the river, in Boston, there’s seven. … I had been in the field for four years and I didn’t know that.

… (Unsure of what to do next) I went around to all different art therapists and learned from them, and realized, oh, my gosh they, literally, had closets full of amazing art work (completed by homeless artists, but tucked out of sight). … I realized, I’ve been in the field for four years and I have no idea these exist. A normal person really has no idea they exist. Why not create a company to help get this artwork out there?

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

And why it is her dream job:

I’ve had so many relationships with homeless and disabled individuals who really just wanted their first break. … A lot of times the stereotypes of homeless individuals are “lazy.” All the individuals I know really just want a break. ArtLifting is helping provide that.

Steve : … you went to Harvard, and most of your classmates probably didn’t end up in this field, but you did, why do you think that was?

Liz : I’ve never applied to a normal job before.

Steve : Why is that?

Liz : I think it’s because I love being curious and seeing problems and trying to solve them. …

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

—

Rocio holds a Ph.D. particle physics and so was drawn to the Lean Startup’s scientific method as she began her venture:

I don’t think many people have any methodology. It’s not that this methodology is better than this one. It’s (that) there’s none. I thought, “Well OK, there’s a higher chance of succeeding, I think, if you have a methodology.”

… The (Lean Startup) methodology is … scientifically based so I can relate to (it) … That’s easy for me to understand about experimentation. The metrics that matter. To measure. To communicate. To learn as you go and iterate. I love the idea of iterations. The best thing is to admit that you don’t know anything until you start, and then you learn as you go.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

She explained that Bidhaa Sasa faces a formidable challenge:

My clients… live in really basic living conditions; their lives are not great. If I could bring the products that help with their quality of life, I think it could have a massive impact in their lives. …

(But) the problem is that the products don’t necessarily reach the people that need them. …

My clients are not consumers … they don’t have much income. They don’t go shopping, they don’t know how to compare products, they don’t even know these products exist. It’s really complicated because you have to really go back to the very basic stages of awareness.

Hence the NGOs are there because the NGOs are really good at awareness. They have plenty of money to create awareness about (issues like) if you keep using dirty water, your kids will be ill, and then (families) make the link between the two and say, “Aah, that’s why they’re always ill, it’s because of the dirty water.” I’m a step behind the NGOs and trying to piggyback on their work, because the awareness is very expensive stuff.

…It is a Last Mile problem. … We are not talking about the last tribe in the middle of the desert. It’s not that at all. It’s the bulk of the East African people. …they live in relatively dense areas so logistics is not necessarily the bottleneck. The bottleneck is, do they know these things exist; can they pay for it?

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

She also explained how, at her first startup, she learned an invaluable skill:

… I got sucked into a full-time job in one of these companies, and then I realized, “Oh, my God, this is so complicated. This is really complicated.”

… we were operating in three countries in East Africa, based in the UK, so operating in emerging markets is quite complicated by definition… It’s relatively fast-paced, and you feel that you’re in a competition, even though I think that is a bit of a misunderstanding when you talk about competition. It was very chaotic. It was completely chaotic.

… I don’t mind, but I could see that there is lots of people don’t deal well with chaos.

I was a manager so I was quite senior in this company, and I had to often pretend that I knew what I was saying, and I was under control because … especially in Africa … there’s another culture, (a) hierarchical structure. They’re expecting to be told what to do, and it’s very different from operating in the western world, so I bluffed all the time and I said everything was under control when it wasn’t. …

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Listen to my full interviews with Liz and Rocio by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here. (And download any of the past shows here.)

Next on Entrepreneurs are Everywhere: Matthew Wallenstein,, chairman and co-founder of Growcentia; and Jason Young, co-founder of MindBlown Labs.

Tune in Thursday at 1 pm PT, 4 pm ET on Sirius XM Channel 111.

Filed under: SiriusXM Radio Show

December 8, 2015

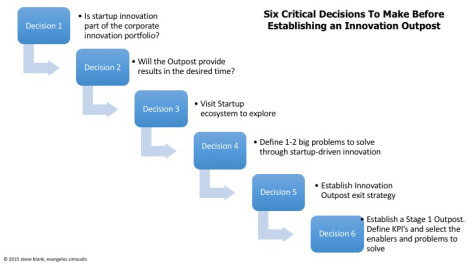

How to Avoid Innovation Theater: The Six Decisions To Make Before Establishing an Innovation Outpost

This is the third in a series about the changing models of corporate innovation co-authored with Evangelos Simoudis. Evangelos and I are working on what we hope will become a book about the new model for corporate entrepreneurship. Read part one on the Evolution of Corporate R&D and part two on Innovation Outposts in Silicon Valley.

—–

Corporate Leadership’s Innovation Outpost Decision Process

Today, large companies are creating Innovation Outposts in Innovation Clusters like Silicon Valley in order to tap into the clusters’ innovation ecosystems.

These corporate Innovation Outposts monitor Silicon Valley for new innovative technologies and/or companies (as emerging threats or potential tools for disruption) and then take advantage of these innovations by creating new products or investing in startups.

Most CEOs assign the responsibility to establish and manage their innovation outposts (and the outpost’s relationships to startups) to their R&D organizations. While that avoids internal management conflict, it’s the wrong way to make an innovation outpost decision.

Instead CEOs and their exec staff should start with a high-level discussion to decide whether their companies should even establish an Innovation Outpost, whether in Silicon Valley or some other innovation ecosystem. Because this is a critical decision that requires broad management buy-in, the conversation should include senior management, particularly the Chief Digital Officer, the Chief Strategy Officer, the Chief Financial Officer, and the Head of R&D, and maybe even their board of directors.

This group needs to carefully consider six key questions to understand if and where an Innovation Outpost makes sense for their company.

1. Do we believe “startup-driven” innovation (innovation that comes from relationships with external, early-stage companies) should be part of the corporate innovation portfolio?

Including “startup-driven” in the corporate portfolio may make sense if a company:

Is being disrupted now, as is happening in many IT, print, retail and telecommunications corporations

Anticipates being disrupted in the near future, as is the case in the automotive and chemical industries

Cannot keep up with the pace of innovation in its industry, as is happening in the pharmaceutical, financial services and consumer packaged goods industries

Wants to promote intrapreneurship to extend its business model and retain creative employees like Google, Amazon, and Facebook do

2. What is the timeline to ROI and the amount of risk we are willing to assume? Will an Innovation Outpost provide results at the speed we need?

An Innovation Outpost focused on the sense and respond model (see Post) will best work for a company when:

A disruption has not already happened or is not imminent. In other words the disruption is expected to happen within 5+ years.

A disruption does not present an existential threat to the corporation, it can be addressed with a relatively modest investment required to establish and expand an outpost, rather than the large investments required for corporate moonshots, e.g., IBM’s Watson. (We’ll cover “corporate moonshots” in a subsequent post.)

Startups are developing IP relevant to the disruption.

Acquiring a growth-stage private startup can provide a faster ROI at lower risk than the acquisition of an early-stage startup. For example, Google’s acquisition of Nest (which had customers, revenue and a distribution channel) allowed it to enter the connected home market immediately. In contrast, Facebook’s acquisition of the virtual reality hardware company Oculus still requires significant product development, identification of a viable business model – and the target market and revenue may never materialize.

If the innovation threats the company faces do not match these, the corporation may need a different approach to addressing the disruption such as making a large scale acquisition, e.g., VMWare’s acquisition of Nicira, merger, or outright selling itself, e.g., EMC’s sale to Dell.

3. W hat would be the charter for our Innovation Outpost?

Senior managers should define the 1-2 big strategic problems that can be addressed through a day-to-day presence in the innovation ecosystem. These challenges may be either strategic or tactical. For example, one of Verizon’s strategic innovation goals for its Silicon Valley organization is to create disruptive solutions (technologies and business models) to monetize the digital media accessed by its subscribers on their mobile devices.

In the process of defining the challenges and goals for an Innovation Outpost, a company must understand why these can be addressed in a particular innovation ecosystem. They may require the utilization of technologies that are prevalent in the ecosystem, (big data or 3D printing) or specialized business models, (on-demand services) or specific innovation practices (design thinking and lean startup) or the development of a particular type of partner ecosystem (IBM’s Watson partner ecosystem.)

Identifying these strategic problems enables the corporation to decide on the location of the Innovation Outpost, define success, and the innovation KPIs that will be used to measure progress.

4. H ow quickly can we get out of the building to explore and validate the ecosystem?

Before committing to a particular innovation ecosystem, the CEO and exec staff need to get out of the building and visit the ecosystem to be assured that the reality on the ground matches the corporation’s innovation challenges. These visits should be led by the CEO, and maybe even include the corporation’s board of directors, along with execs who are expected to be innovation change agents. This exploration requires a deeper understanding than can be accomplished in a single visit.

While the default for most Innovation Outposts is Silicon Valley, it may not necessarily be the best fit for a particular company. Visiting the Valley might help an exec staff understand whether this innovation ecosystem would be right for them. For example, CVS opened its Digital Innovation Lab in Boston as did John Hancock, while Thomson Reuters picked both Boston and Waterloo Canada and Coca-Cola has its Bridge Innovation Lab in Tel Aviv. Exploration may require several visits to each of the innovation ecosystems of interest to pick the right one.

5. What is our company’s strategy for successfully integrating an Innovation Outpost?

Innovation Outposts most often fail when they come up with innovations no operating division wants and/or the company refuses to fund. (The ghosts of Xerox’s failure to adopt their Innovation Outpost inventions that became the Apple Macintosh still haunt Innovation Outposts.) There needs to be prior agreement on what happens if the division develops disruptive products that do not fit the existing company business model. Does it become a new division? Does it get spun out? Sold?

6. How do we establish the Innovation Outpost and staff the innovation enabling group(s) which will be part of the first phase of the Outpost?

Establishing an outpost enables innovation but does not constitute innovation. Once a company has decided to open an Innovation Outpost, it has to choose:

How to leverage startup innovation in the cluster – will the outpost invest, partner, acquire, incubate or invent?

What is the timeline to a ROI for Innovation Outpost? Again, the participation of the senior executives in these decisions is critical.

This process for establishing the Innovation Outpost will be the topic of the next post.

The complete six-step decision process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The decision process for establishing a Corporation Innovation Outpost

Lessons Learned:

To avoid “innovation theater”, Corporations should use a step-by-step decision process to determine the role the Innovation Outpost will play

The decision to establish (and later expand) an Innovation Outpost must be taken by the CEO working with the senior management team

It requires hands-on management by the CEO and the senior executive team

Just saying it has “executive support” means it’s dead-on-arrival

If the Innovation Outpost’s is successful it will almost certainly conflict with other corporate innovation-related decisions.

Just establishing an Innovation Outpost doesn’t mean that the corporation is innovating

At first it just means there’s a new building

The next post will describe How to Set Up a Corporate Innovation Outpost.

Filed under: Corporate Innovation

December 3, 2015

Entrepreneurs are Everywhere Show No. 12: Andrew Breen and David Binetti

Culture matters whether you’re just starting up or innovating inside a big company. And corporate innovation efforts are hampered by the very processes that make big companies successful.

The challenge of innovating inside a big company was the focus of discussion with the two latest guests on Entrepreneurs are Everywhere, my radio show on SiriusXM Channel 111.

Andrew Breen

Joining me at the Lean Startup Conference in San Francisco were:

Andrew Breen, vice president of product delivery for American Express’s World Service division

David Binetti, a serial entrepreneur who owns Dinadesa, which helps organizations innovate faster

David Binetti

Listen to the full interviews by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here. (And download any of the past shows here.)

Clips from their interviews are below, but first a word about the show:

Entrepreneurs are Everywhere airs Thursdays at 1 pm Pacific, 4 pm Eastern on Sirius XM Channel 111. It follows the entrepreneurial journeys of founders sharing their experiences of what it takes to build a startup – from restaurants to rocket scientists, to online gifts to online groceries to entrepreneurial education and more.

The program examines the DNA of entrepreneurs: what makes them tick, how they came up with their ideas; and explores the habits that make them successful, and the highs, lows and pivots that pushed them forward.

Andrew Breen has spent 20+ years developing products and services for mobile, enterprise, e-commerce, media and education companies. He founded the home furnishing site Silver Plum, then went on to work at ThinAirApps, Palm , Medialets and Voxy before joining Amex. Andrew also teaches at NYU’s Stern School of Business.

Culture, he said, is key to the success of innovation efforts, in big companies and new ventures.

There’s always bureaucracy and politics and all different scales. … Some of the hardest conversations I’ve had to have (with startup founders) are “Your vision? We just tried to test and validate that, and it’s not working.”

… The biggest difference is that in a larger company, it’s not about getting the IT department on board or dealing with regulatory and compliance. It’s the culture. …

… There’s a famous quote about show me how you pay and promote and I’ll show you how your company runs…. (Those are the two key levers.)

In startups, people are there for the mission and the purpose, at least you hope you are. In big companies, they’re thinking about their career, and so pay and promotion is a lot of how they optimize (what they work on). …

They get too quickly down to individual goals and … skip over … product goals, team goals and things like that. … People then optimize toward (their own) goals and incentives.

… the interesting thing we’ve realized in technology development (is that there’s an) revolution – you don’t need hundreds and thousands of people to do something really big – small teams need to be there.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

David Binetti is a six-time entrepreneur, having served on the founding teams of USA.gov , Capitolix, and Votizen ; QFN, later Quicken.com ; and Arch Rock, which was acquired by Cisco Systems . Today, he helps Fortune 500 companies apply Lean Startup and Innovation Accounting principles.

He explained the challenges of innovating inside a big company:

(Big corporations) still have to do what entrepreneurs do, which is find customers and figure out the model. (But unlike startups entrepreneurs in large companies) also have to fight against the organization that is actively trying to destroy them… because an existing company has an established business model. …

… The primary function of most businesses is to establish profitably, maintain profit, deliver profit quarter after quarter, systematize your processes so that you’re always delivering a profit.

… so when a company, whose primary function is to generate profit in a repeatable systematic, and predictable way, sees an entrepreneur, they think, ‘Oh, I know what they’re going to do. They’re going to screw everything up.’

(Even) the best companies … find and identify anything that’s disruptive to that and destroy (it). By definition, they do that job well if they find the entrepreneurs and somehow isolate them. …

… The challenge for a large organization is to figure out how do you keep the entrepreneurial search for a new business model from the execution of an existing business model – and how to effectively transition from new innovation to profitable execution. That’s an extremely difficult challenge because the company still needs to do its main job returning profits to its shareholders. But if they’re not planning for the future, then they could get disrupted and be gone in a matter of years right after they, oh, by the way, return record profits. …

…(That two-front war) is … where I’m focusing the majority of my attention, to be able to establish corporate governance structures …policies of the company that they can apply in a systematic way that applies to … their existing businesses, which are designed to generate profitability and should be stable … plus give the opportunity for those who are searching for new business models to function without impedance from the existing business.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

—

Andrew’s parents were serial entrepreneurs. He grew up working in their businesses:

… It was unfathomable for either of my parents to work for anyone else. It was basically, “Go out, set your own course, control your own destiny,” and that kind of rolled into the entrepreneurial spirit. I don’t think we, as a family, ever thought of it that way. I don’t think I, in my early career, ever thought of it that way. It was just, “You have an interesting idea? Go do it.”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Here’s how he learned where he best fits in a new venture:

I learned that commitment – and I understand that better about my parents did – was 24 by 7, (it was) your life and your everything. That’s a pretty good walkaway.

… I love the hard work. … The hundred hours a week on all my startups, that was never a problem. Even in my bigger corporate environments, there’s stress in there. … At the end of the day, you go on the weekend you feel better about that.

There’s not that when you’re the founder. … I used to think entrepreneur and builder were basically the same word. I’ve realized while that Venn diagram does overlap, they are distinct. I’ve learned I’m more in the builder side. When I was the founder, I didn’t love it as much because I couldn’t build. Because I had to deal with investors and look at that benefits plan, and make sure someone was showing up to work, and all those kind of things.

Steve : This is a big idea, that you really need to understand what phase of the company you’re great at and you enjoy having, right? …What you just articulated is that there is one type who is the crazy visionary entrepreneurial founders raising the money and and then there may be someone who helps scale that to the next phase …

Andrew : (Silver Plum was) when I understood that split. …Which I didn’t think there was before. …my career since then has been very focused on that. I’ve had my own ideas, but it’s always been very much on get in early to help scale.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

He especially enjoys building entrepreneurial teams

I’m much better as the facilitator in focusing people. I always said, “get me smart, great people around me, small teams, and get me in there and I’ll get them focused and building.”

A lot of engineering oriented cultures, engineering-oriented people like the problem-solving piece, right? … I love it too, but they can tend to be too focused on just solving the problem, the next step ahead of you, right? It’s part of the engineering discipline.

(But) how do we get to a big vision, and how do we focus on doing that? I found that was actually the thing I was best at. I could write code, I could design, I could do different things, but the ability to actually bring people in around me who had very deep skills in that domain and get them focused and unified around a single problem was the thing that I found, I enjoyed the most and did the best. …

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

—

David told me about his first startup, where he learned that the best laid plans don’t always work out:

… I did everything exactly by the book. … It was called Capitolix, and it was a politically oriented startup that did campaign software delivered online. This was early 2000s. … (We were) automating mailing lists, fund raising, voter contact. Software as a Service at the time was a buzzword.

Steve : You wrote a business plan, with a five-year forecast.

David : Of course. …

Steve : You went out and identified, and spoke to, all the customers and learned what they needed?

David : Of course, after I built it and raised the money… You had to build it first, right?

… It was a complete, unmitigated disaster because what I thought didn’t matter. What mattered is what the customers wanted, and the customers cared about. …

Steve : This startup was an idea you had planned to death.

David : Absolutely. I did a very good job of that.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

David’s advice for other entrepreneurs is straightforward:

They need to test their ideas. In any way that they come up with, test their ideas. If they’re right, there’s nothing lost. If they’re wrong, they have the chance to change and adapt.

(In large companies) … give those same entrepreneurs the opportunity to succeed and fail. Give them the ability to be able to test, without worrying. Develop the tools that you need to, to make sure that you can protect your main business profits, while still giving the opportunity for the entrepreneurs to do their job.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

He also shared why he’s an “entrepreneur in recovery”:

(It’s) a thrilling experience and that feeling that comes with producing something from scratch is something that’s really, really amazing. And managing all of the chaos that’s associated with that is really, really amazing. I also just personally think it’s, you don’t choose to be an entrepreneur. I think it’s an affliction in some way, right? That’s why I say I’m an entrepreneur in recovery because I really think that we’re driven to do it by some force that, if we could take a pill and get rid of, we probably would.

Steve : I liken it to entrepreneurship is a calling, like being an artist. … Or a painter or a sculptor or writer. It’s not a job. …It’s something that …

David : … you’re driven to do it. …

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Listen to my full interviews with Andrew and David by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here. (And download any of the past shows here.)

Next on Entrepreneurs are Everywhere : Liz Powers, co-founder of ArtLifting and Rocio Perez-Ochoa, co-founder of Bidhaa Sasa.

Tune in Thursday at 1 pm PT, 4 pm ET on Sirius XM Channel 111.

Filed under: SiriusXM Radio Show

December 1, 2015

Innovation Outposts in Silicon Valley – Going to Where the Action Is

This is the second in a series about the changing models of corporate innovation co-authored with Evangelos Simoudis. Evangelos and I are working on what we hope will become a book about the new model for corporate entrepreneurship. Read part one on the Evolution of Corporate R&D.

——

Innovation and R&D Outposts

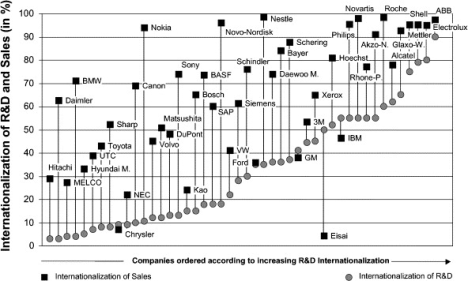

For decades large companies have set up R&D labs outside their corporate headquarters, often in foreign countries, in spite of having a large home market with lots local R&D talent. IBM’s research center in Zurich, GM’s research center in Israel, Toyota in the U.S are examples.

These remote R&D labs offered companies four benefits.

They enabled companies to comply with local government laws – for example to allow foreign subsidiaries to transfer manufacturing technology from the U.S. parent company while providing technical services for foreign customers

They improved their penetration of local and regional markets by adapting their products to the country or region

They helped to globalize their innovation cycle and tap foreign expertise and resources

They let companies develop products to launch in world markets simultaneously

Other companies operating in small markets with little R&D resources in their home country (ABB, Novartis and Hoffmann-La Roche in Switzerland, Philips in the Netherlands and Ericsson in Sweden) pursued R&D outside their home country by necessity.

source: Market versus technology drive in R&D internationalization: M von Zedtwitz, Oliver Gassmann

Innovation Outposts Are Moving To Innovation Clusters

Today, large companies are taking on a decidedly 21st-century twist. They are putting Innovation Outposts into Innovation Clusters -in particular Silicon Valley – to tap into the clusters’ innovation ecosystems.

(An Innovation Cluster is a concentration of interconnected companies that both compete and collaborate. Silicon Valley, Herzliya in Israel, Zhongguancun for software and Shenzen for hardware in China are examples of technology clusters, but so was Detroit for cars, Hollywood for movies, Milan for fashion.)

In the last five years, hundreds of large companies have established Innovation Outposts (and here) in Silicon Valley. The charter of these Innovation Outposts is to monitor Silicon Valley for new innovative technologies and/or companies (as emerging threats or potential tools for disruption) and then to take advantage of these innovations by creating new products or investing in startups.

While that’s the theory, the reality is that to date, most of these Innovation Outposts are at best another form of innovation theater – they make a large company feel like they’re innovating, but very few of these outposts change a company’s product direction and fewer impact their bottom line.

Companies who want their investments in Silicon Valley to be more than just press releases need to think through an end-to-end corporate outpost strategy.

This series of posts offers companies the tools to develop an Innovation Outpost strategy:

Determining whether a Corporate Innovation Outpost is necessary

Planning how to establish an Innovation Outpost

Deciding how to expand the Outpost

Sense and Respond

The first objective of an Innovation Outpost is to sense, i.e., look for or monitor the development of potential innovations that:

Can become threats that could lead to the disruption of the corporate parent. For example, American Express’s Silicon Valley Innovation Outpost is monitoring innovations in financial technologies that are created by companies such as Square. Evangelos and I are in the process of developing a tool for diagnosing corporate disruption through innovations pursued by startups.

Would allow the corporation itself to be disruptive by entering adjacent markets to the ones it currently serves or creating and introducing novel and disruptive offerings for new markets. For example, USAA is looking for software innovations that will enable it to introduce Usage-Based Insurance products to disrupt the car insurance market.

The second objective of the corporate Innovation Outpost is to respond to identified threats and potential opportunities. Companies tend to set up their outposts to respond in one of five ways:

Invent: They establish project-specific advanced development efforts like Delphi Automotive’s autonomous car navigation project or broader Horizon 3 basic research efforts that take advantage of, or investigate, technologies and business models the innovation ecosystem is known for in order to create new products and services. For example, Verizon’s Silicon Valley R&D center focuses on big data and software technologies, as well as online advertising-based business models. Sometimes these Horizon 3 research efforts may be associated with a moonshot the corporation would like to pursue as is the case with Google (Google Car), Apple (iPhone) and IBM (Watson).

Invest: They allocate a corporate venture fund that invests in startups working on technology and/or business model innovations of interest. For example, UPS recently invested in Ally Commerce in order to understand the logistics opportunities arising from manufacturers selling directly to consumers rather than through distributors.

Incubate: They support the efforts of very early stage teams and companies that want to develop solutions in areas of interest–for example, Samsung’s incubator focuses on startups working on the Internet of Things—or they experiment with new corporate cultures and work environments –for example, Standard Chartered Bank’s startup studio.

Acquire: Companies buy startups in order to access both the innovations the startups are developing and their employees, and in the process inhibit competitors from getting them. For example, Google acquired several of the robotics startups that had what was considered the best intellectual property.

Partner: Collaborate with startups in order to develop a disruptive new solution using their innovations along with the corporations or to distribute innovative solutions the start up has developed. For example, a few years ago Mercedes partnered with Tesla in batteries for electric vehicles.

After working with over 100 companies, Evangelos and I clearly see that some of these five responses are more effective than others. Moreover, the speed of the response is as important as the ability to respond. Corporations that establish Innovation Outposts often lose on speed, not on their ability to sense. What makes an outpost an effective contributor versus one that’s simply an expense item starts back at corporate headquarters with a company’s overall innovation strategy. So before we talk about the tactics of establishing an outpost, lets think about what types of discussions and decisions should first happen at the “C-level” before anyone leaves the building.

Lessons Learned

Companies are establishing Innovation Outposts in Silicon Valley

They do this to sense and/or respond to technology shifts

Sense means monitor the development of potential innovations that can become threats or would allow the corporation to be disruptive

Respond means, Invent, Invest, Incubate, Acquire or Partner

Most of these Innovation Outposts will become Innovation Theater and fail to add to the company

The next post will describe The Six Critical Decisions to Make Before Establishing an Innovation Outpost.

Filed under: Corporate Innovation, Science and Industrial Policy

November 21, 2015

Innovation Outposts and The Evolution of Corporate R&D

I first met Evangelos Simoudis when he ran IBM’s Business Intelligence Solutions Division and then as CEO of his first startup Customer Analytics. Evangelos has spent the last 15 years as a Venture Capitalist, first at Apax Partners and later at Trident Capital. During the last three years he’s worked with over 100 companies, many of which established Innovation Outposts in Silicon Valley. He’s now helping companies get the most out of their relationships with Silicon Valley.

Evangelos writes extensively about the future of corporate innovation on his blog.

Evangelos and I are working on what we hope will become a book about the new model for corporate entrepreneurship. His insights about how large companies are using the Valley is the core of this series of four co-authored blog posts.

—-

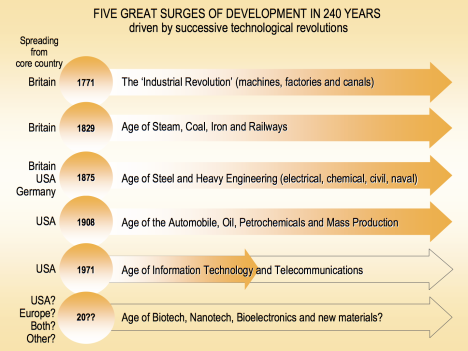

The last 40 years have seen an explosive adoption of new technologies (social media, telecom, life sciences, etc.) and the emergence of new industries, markets and customers. Not only are the number of new technologies and entrants growing, but also increasing is the rate at which technology is disrupting existing companies. As a result, while companies are facing continuous disruption, current corporate organizational strategies and structures have failed to keep pace with the rapid pace of innovation.

This burst of technology innovation and attendant disruption to corporate strategies and organizational structures is nothing new. As Carlota Perez points out, (see Figure 1) technology revolutions happen every half-century or so. According to Perez, there have been five of these technology revolutions in the last 240 years.

Figure 1: Five technology revolutions source: Carlota Perez

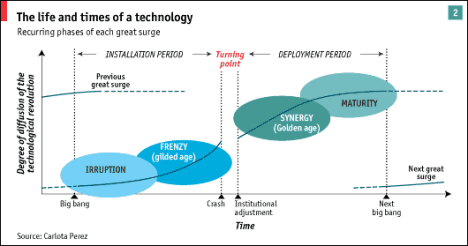

Perez divides technology revolutions into two periods (Figure 2): The Installation Period and the Deployment Period. In the Installation Period, a great surge of technology development (Perez calls this Irruption) is followed by an explosion of investment (called the Frenzy.) This is followed by a financial crash and then the Deployment period when the technology becomes widely adopted. In between the Installation and Deployment periods lies a turning point called Institutional Adjustment when institutions (companies, society, et al) adjust to the new technologies.

Figure 2: The two periods characterizing technology revolutions source: Carlota Perez

Historically during this Institutional Adjustment period companies have to adjust their corporate strategies to deal with these technology shifts. The change in corporate strategy forces a change in the structure of how a company is organized. In the U.S. we’ve gone through three of these structural shifts. We’re now in the middle of the fourth. Lets quickly review them and see what these past shifts can tell us about the future of corporate R&D.

Institutional Adjustments

In the first 50 years of commerce in the then-new United States, most businesses were general merchants, buying and selling all types of products as exporters, wholesaler, importers, etc. By 1840 companies began to specialize in a single type of goods like cotton, wheat or drugs, etc. and concentrated on a single part of the supply chain – importing, distribution, wholesale, retail. This shift from general merchants to specialists was the first structural shift in American commerce.

These specialist companies were still small local businesses. Ownership and management were one and the same – the owners managed, and there were no salaried middle managers or administrators.

In the 1850’s and 60’s, the railroads changed all that. The railroads initially served a region of the country, but very quickly grew into nationwide companies. The last quarter of the 19th century, what Perez calls the Age of Steel and Heavy Engineering, saw the growth of America’s first national corporations in railroads, steel, telegraph, meatpacking, and industrial equipment. These growing national companies were challenged to figure out how to organize an organization of increased complexity that resulted from their large size, and geographic scale as well as their horizontal and vertical integration. For example, US Steel had integrated vertically and was involved in the mining of the iron ore all the way to the production of various steel products, e.g., nails. These new corporate strategies drove companies to build structures around functions (manufacturing, purchasing, sales, etc.) and to develop professional managers and management hierarchies to run them. Less than 50 years later, by the beginning of the 20th century, the modern form of the corporation had emerged. (For the best explanation of this see Chandler’s The Visible Hand.) This shift from small businesses to corporations organized by function was the second structural shift in American commerce.

By the 1920’s, in Perez’s Age of the Automobile and Oil, companies once again faced new strategic pressures as physical distances in the United States limited the reach of day-to-day hands-on management. In addition, firms found themselves now managing diverse product lines. In response, another structural shift in corporate organization occurred. In the 1920’s companies moved from monolithic functional organizations (sales, marketing, manufacturing, purchasing, etc.) and reorganized into operating divisions (by product, territory, brand, etc.), each with its own profit and loss responsibility. This strategy-to-structure shift from functional organizations to operating divisions was led by DuPont and popularized by General Motors and quickly followed by Standard Oil and Sears. This was the third structural shift in American commerce.

The 1970’s marked the beginning of our current technology revolution: The Age of Information Technologies, Telecommunications and Biotech. This revolution is not only creating new industries but also affecting existing ones – from retail to manufacturing, and from transportation to financial services. We are now somewhere between the end of Installation and the beginning Deployment – that confusing period between the end of the Frenzy and the beginning of the Turning Point, during which time institutional adjustments are necessary. Existing companies are starting to feel the pressures of new technologies and the massive wave of new entrants fueled by the explosion of investment from a recent form of financing – venture capital. (Venture capital firms, as we know them only date back to the 1970s.) Companies facing continuous disruption need to find new corporate strategies and structures. This fourth structural shift in American commerce is the focus of this series of blog posts. In particular, we are going to focus on how each of these shifts has changed the organization and role of Corporate R&D.

Corporate R&D Evolves With Each New Structural Shift

Each institutional adjustment also changed how companies innovated and built new products. During the Age of Steel and Heavy Engineering in the 1870’s to 1920’s, innovation occurred outside the corporation via independent inventors and small companies. Inventors such as Thomas Edison, Alexander Graham Bell and Samuel Colt come to mind. Patents, inventions and small companies were sold to larger corporations. By the 1920’s, in the Age of the Automobile and Oil, large companies sought to control the new product development process. To do so they brought innovation and invention into the company by setting up storied Corporate R&D Labs such as GE Labs, DuPont Labs, Bell Labs, IBM Research, 3M, Xerox PARC, and Kodak Labs. By the 1950’s Shumpeter observed that in-house R&D had replaced the inventor-entrepreneur. The technology cycle was in the Synergy and Maturity phase, and little innovation was happening outside of companies. It was corporate R&D labs that set the pace of innovation in each industry.

As the Age of Information Technologies and Telecommunications gained momentum in the 1970’s, the Irruption phase of this new technology cycle created an onslaught of new startups funded by venture capital. Think of companies like Apple, Digital Equipment Corporation, Sun Microsystems and Genentech. The beginning of a new technology cycle didn’t come with a memo or a formal announcement. Corporate R&D and Strategy groups that had been successful for the past 70 years were finding their traditional methods no longer worked.

Historically Corporate Strategy and R&D groups worked hand-in-hand to keep companies competitive. They were adept at analyzing competitors, trends, new technologies and potential disruptors to the corporation’s business. Corporate Strategy would develop plans for new products, and R&D would then create and patent the disruptive innovations. Tasked with “looking over the horizon,” Corporate R&D and Strategy organizations looked at the last technology cycle and the existing incumbents instead of seeing the new technology cycle and the new wave of startups.

Corporate R&D in the Age of the CEO as Chief Execution Officer

Ironically as the new technology cycle went from Irruption to Frenzy (remember Perez’s stages of technology revolutions), existing corporations headed in the other direction. Over the past 15-20 years as startups were funded with ever-increasing waves of investment, companies have cut back their investment in innovation. Corporations focused on financial metrics like Return On Net Assets and Internal Rate of Return to reap the benefits of the last technology cycle. This meant R&D organizations have been pushed to work more on D (development) and less on R (research.) Researchers addressed short-term, Horizon 1 problems (existing business models, last technology cycle) rather than working on potentially disruptive Horizon 3 ideas from the next technology cycle. (See here for background on horizons.)

As a result, corporate R&D organizations have been producing sustaining innovations that protect and prolong the life of existing business models and their products and revenue streams. While this optimizes short-term Return On Net Assets and Internal Rate of Return, it destroys long-term innovation and investment in the next technology cycle.

While that’s the good news for short to mid-term revenue growth, the bad news is that corporate R&D’s is investing much less on disruptive new ideas and the next technology cycle and instead focusing on the development of incremental technologies. The result is a brain-drain of researchers who want to do the next big thing. Corporate researchers are voting with their feet, leaving to join startups or to start companies themselves, further hampering corporate innovation efforts. Ironically as the general pace of innovation accelerates outside companies, internal R&D organizations no longer have the capability to disrupt or anticipate disruptions.

Because of declining corporate investment in disruptive research and business model innovation, the typical corporate R&D organization can’t:

Keep up with technology innovations: Even corporations with high R&D spending are concluding that their existing R&D model cannot keep pace with exponential technologies and the accelerating pace of information technologies, biotechnologies, and materials

Address the global creation of innovation: Disruptive innovation is now created around the world by companies of any size, many of them startups. These companies are funded by abundant capital from institutional venture investors, private investors, and other sources. Our hyperconnected world is amplifying the effects of these companies and enabling them to have global impact, as seen with companies from Israel, India, China, and Brazil

Properly align technology with other types of innovation: Corporate R&D remains focused on technology innovation. Certainly these organizations have little, or no, ability to appreciate and create other forms of innovation

By the 1990’s corporate innovation strategies changed to a focus on startups—investing in, partnering with or buying them. Companies built corporate venture capital and business development groups.

But by 2010, this technology cycle moved into the Frenzy phase of innovation investment. Corporate R&D Labs could not keep up with the pace of external invention. Increasingly corporate venture capital involved too long of a lead-time for corporate technology investments to pay off.

To adapt to the current frenetic pace of innovation, corporations have created a new organizational structure called the Innovation Outpost. They are placing these outposts at the center of the source of innovation: startup ecosystems.

The next 3 posts will explore the rise of Innovation Outposts, Six Critical Decisions Before Establishing an Innovation Outpost and How to Set Up a Corporate Innovation Outpost for Success.

Be sure to check out about the future of corporate innovation on Evangelos Simoudis blog.

Filed under: Corporate Innovation, Science and Industrial Policy

November 18, 2015

Entrepreneurs are Everywhere Show No. 11: Pat Sullivan and Sebastian Jackson

Startup founders strive to turn their dreams into reality, and the mentors who guide them often learn as much as they teach.

How startup ideas are developed and nurtured was the focus of conversations with the latest guests on Entrepreneurs are Everywhere, my radio show on Sirius XM Channel 111.

Pat Sullivan

Joining me in the Stanford University studio were:

Pat Sullivan, CEO of Ryver, a team communication tool

Sebastian Jackson, CEO and founder of The Social Club Grooming Company, a community barbershop on the midtown campus of Wayne State University

Sebastian Jackson

Listen to the full interviews by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here. (And download any of the past shows here.)

Clips from their interviews are below, but first a word about the show:

Entrepreneurs are Everywhere airs Thursdays at 1 pm Pacific, 4 pm Eastern on Sirius XM Channel 111. It follows the entrepreneurial journeys of founders sharing their experiences of what it takes to build a startup – from restaurants to rocket scientists, to online gifts to online groceries to entrepreneurial education and more.

The program examines the DNA of entrepreneurs: what makes them tick, how they came up with their ideas; and explores the habits that make them successful, and the highs, lows and pivots that pushed them forward.

Pat Sullivan is a serial entrepreneur who has been building software for more than 30 years, starting with the ACT! contact software he created in 1985. Pat was named one of the “80 Most Influential People in Sales and Marketing History” and was twice named Ernst & Young “Entrepreneur of the Year” for both ACT! and SalesLogix software.

Having had terrific mentors over the years, Pat makes it a point to pay his what he’s learned forward. He’s learned that mentorship is a two-way street:

I … meet with any entrepreneur who has a legitimate idea, or is in the process of starting something, for two reasons. One (is to) give back. The other is, I find that I always learn something. Younger people than I, they’re into things that I’ve never thought of. (For example) I thought Twitter was a really stupid idea, until my kids explained that it really wasn’t. I always learn something extraordinarily useful by meeting with others.

… There are many times where I don’t fully understand what exactly it is that they’re trying to do, and the domain expertise that they have … but there are many things that are general in nature, that I have that they don’t have, and that I can give to them.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Here are some of the things his mentors taught him:

Once I was agonizing over the fact that it took me a really, really long time to recognize that an executive … I hired just wasn’t making it. … It took me forever to decide to fire him. I … talked to my mentor and I was complaining how long it took. He listened, and listened, listened, just quiet, and all of a sudden he said, “You know, I think it’s great that everybody back at the office knows that you’re not quick on the trigger.” It totally … changed my perspective.

Another … mentor … said …: “You know, I may not be the smartest, I may not be the richest, but I can out-work you.” …

That has always stuck with me, that I’m not the smartest, I’m not the brightest, I may not have the most money, but I can out-work you.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Sebastian Jackson got his start cutting hair and dreaming of the day he might have is own barbershop. He said his early life had a profound impact on the way he thinks:

Sebastian : My mother, she suffers from schizophrenia. She was diagnosed when I was 1 (or) 2 years old. She’s always had this imagination as a part of that illness. It’s kind of helped me imagine things, right? …. Also I have to work, to execute on that imagination, just so that I know I’m not suffering from the same illness, that if I execute then it’s real.

Steve : There is a fine line between insanity and genius.

Sebastian : There is. In America, I think it’s money; if you can make money from your illness, then you are deemed a genius.

Steve : I mean, that is kind of … it’s interesting you say that. I don’t mean to diminish what you went through with your mom but founders with big visions are treated as insane by most people who kind of go, “What do you mean you’re going to create a rocket company?” Or, “What do you mean you’re going to put the auto industry out of business?

Sebastian : Delusions of grandeur.

Steve : … I think you said the magic word, the distinction between entrepreneurs and just people with ideas are they figure out how to get the resources to actually execute. …

Sebastian : Absolutely. …Oftentimes thought I was crazy but then … another opportunity will present itself or I will create another opportunity and be able to execute on it and that … validated my thinking. …

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

—

Both men are self-motivated and driven.

Pat explained that when he was a computer salesman, he created programs that eased his work problems and challenges. They became the foundation for ACT!

Being in sales, it struck me that, here I was selling computers but couldn’t find a really good reason to actually use one.

… You could some word-processing, a little spreadsheet-type stuff but there wasn’t really anything useful to me as a salesperson. For whatever reason, I began to teach myself programming and built what ultimately became the prototype for the product ACT!

I did it (on the side) for about three years while I was selling computers. I was building applications that I use day in and day out. Anything that was routine, I hated routine so I would figure out how to program that. The last thing that I built was a contact manager, the ability to track all the information about my prospects, about my customers, so that I could remember them. …I solved a problem that I had.

… I really wish I could say that it was an overnight success. But April of 1987, we shipped the first version of ACT! My partner and I (had finally) decided to do a startup.

Steve : That was pretty scary, wasn’t it?

Pat : I was a risk-taker. My wife and I discussed it with my partner and his wife over a weekend. I had put a couple of years into building this application. My wife said, “What’s the worst that could happen?”

Well, in Texas, which is where we were at the time, they couldn’t take your house. They couldn’t take one of your cars and they couldn’t take your kids. She said, “If that’s the worst that can happen, then you ought to try it because if you don’t, you’ll never know.”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Sebastian also took a hands-on route:

… Before I started cutting hair for other people, I cut my own hair. … It was a pretty good haircut. … I just used a Schick razor and lined up the edges of my hair. Didn’t cut any off the top. I gave myself kind of a little taper or fade on the side and the back, and it was decent. Used my dad’s clippers. …

It was spring break. I saw other people doing it. My barber did it and I said, “If he can do it, I can do it.” …

Now, that first time kind of validated that I had the ability. The second time, I was so confident that I had actually tried to cut the top down. I left patches and everything everywhere. … It was terrible. …

I went to the barber, and he fixed it.

That first time stuck with me though. I had the confidence that I could do this and I continued to do it.

… From my sophomore year, when I was 15 years old, I started making five bucks a haircut, three bucks a shape-up, and started to travel to different clients in their homes, in their parent’s homes. I made a little bit of pocket change in high school, out of my parent’s garage, and out of other friends’ basements and garages.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Sebastian has a founder’s signature tenaciousness. He had to write four business plans to get the OK to open his barbershop.

Wayne State saw that the previous business had failed, so they said, “No, no, no. No non-profit. We’ve got to make money here. How are you going to pay us?”

I wrote a second business plan and it showed how I would pay them. (It showed) the support I had to raise money to pay them and they still didn’t like that.

The third business plan was a for-profit showing an actual business model. It was very simple. We’re going to cut hair, people are going to pay us money, and then we’re going to pay you a portion of that.

… They said, “You’re onto something here.”

The fourth one was the social club, which explained how we would create impact within this space …

… Wayne State wanted to create a campus where student life was abundant, where they can really have students live on campus and have a great time. We showed how we could add value there …how we could use a barbershop to create a place where students could come and have a good time, and get a service that actually make money. A service that … they’re willing to pay for. …

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

The Social Club Grooming Company has become a community hub, in part because of its Shop Talk monthly panel discussions.

… We bring people of interest in; they tell their story while getting a haircut.

…As you’re getting your hair cut, you’re on the panel with maybe one other person and it’s a traditional barbershop talk. It’s an audience of people sitting around these 2 barber chairs. We take our other six barber chairs out of the way and we have two barber chairs that are front and center. People sit around and you tell your story. I moderate and then there’s a Q&A between you and the audience. It’s a TED talk in a barbershop.

… The real stickiness here is we’re able to have these unfiltered conversations … where you can tell us some secrets that you may not be willing to talk about in a traditional panel discussion setting.

The barbershop breaks (down social) barriers. If Reggie Bush comes in and does a Shop Talk, or if whomever comes in to a barbershop and there’s a line (to get a hair cut), they have to wait. You’re no longer this celebrity. You’re no longer this influencer

…It’s a leveler and I think people really appreciate that about the barbershop heritage. … I think … my team … can … execute this and I think it’s because of my … being an entrepreneur and a highly technically skilled barber.

I understand the barbers and I understand a bit about business and I’m asking a lot of questions and I’m getting opportunities like this when I can ask you more questions. … Also, in interacting with our customers every day, I can learn quite a bit. I can ask them questions and really figure out what they want, what they want to pay for, so on and so forth. …

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Pat discussed the characteristics of world-class founders and told me why he can’t imagine doing anything else.

Tenacity.… persistence … perseverance. I like the word perseverance because the word severe is in it, and you often face things that are severe. An entrepreneur who is formidable typically finds a way to get through it. I love the book, The Hard Thing About Hard Things (by Ben Horowitz) that there’s always a way …

Steve : So why do you still do it, after 30 years?

Pat : Well, first of all, it’s the only thing I get paid for, so it makes me a professional. I would be totally unemployable, there’s no one who would hire me, because they always know I’m going to do another startup. (And) doing something with particularly young, really, really bright people, doing something that’s hard, is just a lot of fun. …

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Listen to my full interviews with Pat and Sebastian by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here. (And download any of the past shows here.)

Next on Entrepreneurs are Everywhere : Andrew Breen, Vice President of Product Delivery for American Express’s World Service division; and David Binetti, founder of Dinadesa , from the Lean Startup Conference .

Tune in Thursday at 1 pm PT, 4 pm ET on Sirius XM Channel 111.

Filed under: Customer Development, SiriusXM Radio Show

November 17, 2015

Lean Startup In Japanese Companies

Implementing the Lean Startup in any company is hard. All the culture and incentives are designed for execution. Innovation at times seems like you’re swimming up hill. Now compound that level of effort with trying to put a Lean Startup culture in place in Japan.

According to Takashi Tsutsumi and Masato Iino, Japanese companies tend to be technology centric, obsess over quality and have weak leadership. Technology centric leads to companies ignoring their customers and the challenge is that they don’t do customer interviews. The obsession with quality leads to a silo mentality and a mania for procedure, the challenge is a lack of flexibility. And weak leadership leads to a reluctance to change and the inability to mandate Lean as an innovation process.

They list four actionable steps for implementing Lean in Japanese corporations. I think they’re relevant for all companies.

If you can’t see the presentation click here

Filed under: Corporate Innovation, Customer Development Manifesto

November 11, 2015

Entrepreneurs are Everywhere Show No. 10: Reetu Gupta and Mandela Schumacher-Hodge

A startup is not a part-time activity. Trying to do a startup while keeping your day job may doom you to failure. So will failing to understand your customers.

Successful founders have a laser-like focus and commitment; a keen understanding of customers’ needs; and a tenacious spirit, said the latest guests on Entrepreneurs are Everywhere, my radio show on Sirius XM Channel 111.

Reetu Gupta

Joining me in the Stanford University studio were:

Reetu Gupta, co-founder and CEO of CirkledIn, an online platform that compiles students’ school life achievements

Mandela Schumacher-Hodge, founder of The Startup Couch, which aims to help founders stay happy and healthy as they change the world

Listen to the full interviews by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here. (And download any of the past shows here.)

Mandela Schumacher-Hodge

Clips from their interviews are below, but first a word about the show:

Entrepreneurs are Everywhere airs Thursdays at 1 pm Pacific, 4 pm Eastern on Sirius XM Channel 111. It follows the entrepreneurial journeys of founders sharing their experiences of what it takes to build a startup – from restaurants to rocket scientists, to online gifts to online groceries to entrepreneurial education and more.

The program examines the DNA of entrepreneurs: what makes them tick, how they came up with their ideas; and explores the habits that make them successful, and the highs, lows and pivots that pushed them forward.

Before starting CirkledIn, Reetu Gupta spent 20 years in corporate America doing internal startups as well as marketing and engineering work at Fortune 50 companies including AT&T Wireless and Honeywell. In between, she started a wearable startup in her spare time, but failed. Here’s what happened:

Timing the market is a critical piece of any successful startup. We were early to the market. Even though there was a real need in the market it wasn’t right (the right time) for a wearable (product). Today, everybody is wearing an Apple watch, five years ago, not so much.

… another reason (we failed was that it was a) side project. …The thing is, when you do it as a side project, one, you don’t have enough fire under your feet. … You have consistent paycheck coming in. There’s no reason for you to freak out and you’re not running out of money and you’re not trying your best (and) your resources are diffused. …

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Named to Forbes 30 Under 30 in Education list in 2014, Mandela Schumacher-Hodge is a former high school teacher who later served as global director of Education Entrepreneurs, a Gates Foundation initiative operated within UP Global, now Techstars. Her first startup was Tioki, known as the LinkedIn for educators.

While building Tioki, Mandela fell under the spell of her own reality distortion field:

One of the biggest lessons I learned was really understanding the problem… of your user. …. You think they want your product … or you think because you are one of those users everyone would want what you want. I think that I gave myself a little bit too much power in the sense of, well, I’m a teacher; I know what all teachers would want, instead of getting out of the building and really practicing those early skills I learned at Startup Weekend. Get out of the building and really talk to people. Really understand their pain points. …

… I (also) wish I would have just understood how this industry works a little bit better,” before jumping in, just so my expectations would be equal to what the circumstances would require of me, like constantly learning and iterating and being super agile. I don’t think I had ever had to be that way in my other career paths. That is a for sure requirement of entrepreneurship that I wasn’t aware that I would … I thought, “Oh, we’re getting funded. We made it.” But that’s just the beginning.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Playing sports helped prepare her to be an entrepreneur:

The elements I learned from being an athlete, as well as a captain (are) first and foremost … being a teammate. I think that you can be an individual and build a great product, but in order to really turn it in to a fantastic sustainable company, you really have to understand team dynamics, and you really have to understand complementary roles and skill-sets, and how to position people in the right seats, at the right time, depending on where you are at, in a season, or in a game and, of course, (in) your startup life…

Steve : … Team captain is a lot like the founder and CEO of a startup. We talk a lot about (how) startups need teams with complementary skills. … When you get a monoculture, you sometimes have a less successful startup. …

Mandela : … The teamwork aspect is huge. … Aside from teamwork, I would say a huge thing I learned was perseverance by being an athlete. When you want to give up, and you’re tired physically, mentally, and the effort it takes to just keep going, get up one more day, I have oftentimes found that’s when I score that last-minute goal. It’s the same thing in my entrepreneurial career: If I just stick with it and I put myself in uncomfortable situations, that’s oftentimes … where success is found.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Mandela gave up a Ph.D program to become an entrepreneur:

…I was on my way to the Ph.D… that I had worked my behind off to get into. It was a really big conundrum for me.

… I tend to feel like sometimes I am Super Woman. Like I can do everything. … (so) I was going to do both — naivete, right? So I started my PhD program. I did that for several months, and I started building the Tioki … with my co-founder.

…and I got quickly pushed on my behind — humbled you can call it — and I realized that I’m being good at two things but I’m not being great at either. I understood the importance of making a decision and having a laser-like focus to really hone in my energy, my time, everything on one thing. So I made the decision to drop out of the Ph.D program and take the plunge full time.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Today she is applying the lessons she learned from her Tioki experience to The Startup Couch: