Steve Blank's Blog, page 23

October 11, 2016

Entrepreneurs are Everywhere Show No. 45: Dan Miller and Brian Zuercher

I always told myself that I would stop pushing forward when there was an overwhelming force from the outside saying that this is not working. But even when I reached that point, I continued to try to brute force it into existence. I wound up losing a lot.

We followed every test and experimental process from the get-go but we didn’t tell our investors we were doing that. They still thought we were building what we had presented in a PowerPoint slide. When they found out, they questioned my decision-making and me as an entrepreneur.

The same passion that got your startup idea off the ground can blind you to signs that your company is failing.

And not keep investors informed about changes to your business model can have serious consequences.

How to recognize when it’s time to pull the plug on your startup idea, and why founders can’t operate afford to operate in a vacuum were the focus on today’s Entrepreneurs are Everywhere radio show.

The show follows the journeys of founders who share what it takes to build a startup – from restaurants to rocket scientists, to online gifts to online groceries and more. The program examines the DNA of entrepreneurs: what makes them tick, how they came up with their ideas; and explores the habits that make them successful, and the highs and lows that pushed them forward.

Dan Miller

Joining me in the Stanford University studio were

Dan Miller, co-founder of Level Therapy, provider of mobile therapy sessions

Brian Zuercher, founder of Seen marketing platform software

Brian Zuercher

Listen to my full interviews with Dan and Brian by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here

(And download any of the past shows here.)

Clips from their interviews are below.

Dan Miller is the co-founder and CEO of Level Therapy, which provides access to psychotherapists through video, voice, and text. Before Level, Dan was the founder and CEO of Freshsessions, the world’s first marketplace for musicians to find and book studio time anywhere.

Before setting out on his own, Dan held various product, research, and operations roles at Salesforce, SurveyMonkey, Forrester Research, and The Ladders. He was also on the team that wrote the business plan for BlackGirlsCode. In 2014, Business Insider listed Dan as one of the top 46 African Americans in Tech.

With Freshsessions, Dan thought he was on to a great idea. Other people thought so, too, but weren’t willing to pay for the service:

It was going pretty well at the very beginning. We built a landing page, and ran some ads, and started to drive targeted traffic to the ads to see if people would be interested in it.

There was a lot of interest. But it was very difficult to find engaged studio owners that wanted to change how they were operating their businesses to adopt a technology-based model, and find musicians that had enough money to book consistent sessions through the platform.

We found the need, but no payers.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

He wanted Freshsessions to work so badly that he was tone-deaf to signs that it was time to shut the business down:

I always told myself that I would stop pushing forward when there was an overwhelming force from the outside saying that this is not working. Even when, I believe, in hindsight, that I reached that point, I continued to try to brute force it into existence.

We were trying out different cities, and I was flying around the country, and we were trying different campaigns and various things, and ultimately they were not working.

Through that process, I lost a lot including some relationships with individuals, and I started to develop symptoms of acute anxiety.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Brian Zuercher is the CEO and co-founder of Seen, a marketing software platform that is helping marketers tell the story of their brand and build relationships with their customers through consumer generated photos and videos. Seen was recognized as the “Innovation Game Changer” at the 2012 Ohio Interactive Awards.

Actively involved in the local startup community, Brian is a Startup Weekend Columbus host and MC at the monthly morning pitch event for entrepreneurs, WakeUp StartUp.

Additionally, he has an extensive background in building and launching consumer products at Seen, Clearwish (founder), and Woods Industries.

Today, Seen has achieved some success, but it took Brian and his team several pivots to get where they are. They didn’t always keep their angel investors informed about the changes they were making and it nearly cost them:

We followed every test and experimental process from the get-go but we didn’t tell our investors we were doing that. They still thought we were building what we had presented in a PowerPoint slide as the product, but that didn’t work out in our case.

We did three iterations of the product in less than 12 months, each one progressively going off of different consumer metrics that we found and then partner feedback.

Ultimately, it didn’t work and we decided we had enough time to maybe do one last iteration. We did the tough thing of letting everyone go, reducing the burn down to two of us from almost 10 at one point, and gave ourselves six weeks to turn into a new product.

Meanwhile, the investors thought we were dead. We’d told them, “Hey, we let everyone go. We’ve got some money left, but we don’t know if we’ve got much left.”

They questioned my decision-making and me as an entrepreneur. Fortunately we had the confidence of a couple board members as well who were able to stand up for us.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

—

Seeking help to cope with the anxiety he developed as Freshsessions was falling apart, Dan tried some web-based mental health practitioners. The experience wasn’t positive, and led him to come up with the idea for Level Therapy:

I tried one that was solely web-based, with an interesting subscription model, but they didn’t accept insurance. I walked away from that experience feeling cold, and more like a number than a person.

Immediately, the entrepreneur in me started to kick in, and I started to think about why, objectively, was I having those thoughts? Where did this company miss? How could I build a solution that would address those points?

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Dan suggests other founders seek out not just a single mentor but a network of fellow entrepreneurs that can act as a kind of advisory board:

I would aim to find other entrepreneurs that are perhaps six months ahead of where you currently are as a company, or six months to a year or two years ahead of where you are, so they are contemporaries that have experience, potentially the same types of challenges that you’re experiencing. They can give you timely advice.

Also, individuals that are further out, so perhaps they have either sold companies or they’ve been operating companies for three plus years, five plus years, etc. They can give you more long-term strategic advice.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Based on his experience with Freshsessions, he also counsels founders to never work with friends:

It was difficult to overnight go from being someone whose relationship was based around just having fun to actually motivating them and inspiring them and pushing them.

Maybe that was a function of me being young in my professional career as well, but that was my experience. I wouldn’t do it again.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

—

In his first startup, Clearwish, Brian learned it isn’t enough to focus on trying to realize your vision. The founding team must be on the same page about possible future directions for the company, too.

We were approached to get funded and had enough success and promise at the time, but we couldn’t find alignment around the notion of building a lifestyle business first, a venture-based business, and how big it could really be.

We had never discussed everyone’s expectations when we founded the company. Oh we had a happy, fun conversation over a couple of beers, but we did not sit down and say, ‘Hey wait, where’s everyone want to go with their life?”

Instead, we launched the product, got momentum very quickly, and were swept up in this process. We misfired on that and broke down that team. It was a learning experience for sure.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Having worked with startups in Columbus, Ohio, Brian says it’s not necessary to be in a startup ecosystem to make your startup work:

When I was complaining about raising money in Columbus many years ago, Bill Diffenderffer, who ran SkyBus and is now one of the founders of Silvercar, told me, “You keep saying here, but there is no here here, so just go get the money.”

That really stuck with me. The place isn’t necessarily going to make the business go.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

His advice for other founders? Think big:

I think I try to ask all the questions that I’ve been asking myself, like why are you doing this? Why are you making the decision? Why are you looking at that? Is this what you believe is right for the business versus right for what some financier asked you to do? I push them to think really big.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Listen to my full interviews with Dan and Brian by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here (And download any of the past shows here.)

Coming up next on the blog: Emily Kennedy, founder and CEO of Marinus Analytics; and Chris Cabrera, founder of Xactly

Tune in Thursday, Oct. 13, at 1 pm PT, 4 pm ET on Sirius XM Channel 111 to hear these upcoming guests on Entrepreneurs are Everywhere: George Zimmer, founder of Men’s Wearhouse and now founder, chairman and CEO of Generation Tux; and Scott Adams, creator of Dilbert

Filed under: Customer Development, SiriusXM Radio Show

October 10, 2016

Entrepreneurs are Everywhere Show No. 44: Jacqueline Ros and Christina Stembel

The first two years of my startup were the most challenging years of my life; I just felt like a complete failure all the time.

In moments of darkness you need to remember why you’re here and why you’re fighting that fight.

Grueling. Demoralizing. Chaotic. Miserable.

Most first-time entrepreneurs aren’t prepared for the challenges they will face building a startup, and yet they wouldn’t trade the experience for anything.

How founders find the determination to push through tough times was the focus on today’s Entrepreneurs are Everywhere radio show.

The show follows the journeys of founders who share what it takes to build a startup – from restaurants to rocket scientists, to online gifts to online groceries and more. The program examines the DNA of entrepreneurs: what makes them tick, how they came up with their ideas; and explores the habits that make them successful, and the highs and lows that pushed them forward.

Jacqueline Ros

Joining me in the Stanford University studio were:

Jacqueline Ros, co-founder and CEO of Revolar wearable safety devices

Christina Stembel, founder of Farmgirl Flowers, an ecommerce floral delivery company

Christina Stembel

Listen to my full interviews with Jacqueline and Christina by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here

(And download any of the past shows here.)

Clips from their interviews are below.

Jacqueline Ros left a teaching job to found Revolar. She and her team ran a successful Kickstarter campaign, went through the Techstars Boulder 2015 accelerator program, and recently closed a $3 million financing round with The Foundry Group.

Jacqueline’s goal for the company is to change the way women keep themselves and those they love safe.

She had no startup experience going in and was surprised by the learning curve she faced. Here’s what she tells other first-time founders:

In moments of darkness you need to remember why you’re here and why you’re fighting that fight.

You have to be obsessed with what you’re doing. You have to believe, especially if you have no idea, and you’re coming from a completely different background than tech or entrepreneurship.

You have to be 1000% dedicated to the mission and the problem you’re trying to solve and always be customer focused, because it is a long ride.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

Christina Stembel dreamed up the idea for Farmgirl Flowers in 2010 after gaining experience across a variety of industries including hospitality and event planning. Her goal was to start a business that was not only innovative and creative, but did some good in the world.

Her idea for creating signature daily arrangements of locally grown flowers disrupted the floral delivery industry, but Christina quickly found herself overwhelmed:

The first two years were the most challenging years of my life; I just felt like a complete failure all the time.

I would go to networking events and everybody had like a sappy smile on their face and all the stories I was hearing was how much funding everybody had raised and how great everything was and how they had free lunch and all that stuff. I was like, I just switched from coffee to tea because tea bags are like 16 cents a piece and I can’t afford coffee right now.

I just felt really alone and I felt like nobody else was feeling that way. Now that I amd on the other side and can have coffee again, I want to tell people that because I feel people are ashamed to say it.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Everybody glosses over how lonely you’re going to feel, but this is really hard. It’s excruciating.

You’re going to cry. You’re going to feel like you’re going to fail all of the time. You’re going to be scared all the time.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

—

Revolar is a wearable device that allows users to alert a preset list of contacts at the click of a button if they are feeling unsafe or in need of help.

Jacqueline came up with the idea after her sister was attacked twice. By talking to people, including students on college campuses, she found that she was on to something. Then she went to work on the technology:

I hired some contract engineers who used to work on the Life Alert product to build us a really dinky prototype that you could plug into the wall. And I found a couple who worked out of their house to build me a really chintzy app.

If you plugged this prototype into the wall, it would send an alert.

That was enough to get our Kickstarter campaign going.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

—

She explains why they turned to Kickstarter and what happened with their campaign:

We kept hearing from investors, “Who are your customers? How do you have proof that they’ll pay for this?” Kickstarter was the only platform we could think of to prove that people would buy our product.

We naively thought we would have a viral campaign, but it took us 4 months to create and cost us $25,000. It was an incredible undertaking, and we had the hustle for every last dollar.

By the end of the 45-day campaign, we had 1,200 pre-orders.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Today, Revolar has retail partnerships with Brookstone, Best Buy and Amazon. Here’s one thing Jacqueline wishes she’d done differently.

I wish I had talked to an accountant before I talked to a lawyer, because if we had established ourselves as a S Corp or an LLC in the beginning, I could have gotten a lot of my own money back and then reinvested it in the company.

It would have been great in the Ramen noodle days to have the ability to get money back to reinvest in what we were doing.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

—

Christina started Farmgirl Flowers with $49,000 in her bank account. She set herself up at her dining room table, watched YouTube tutorials on flower-arranging and gave herself two years – or until she ran out of cash – to build the business.

The money didn’t last. She came precariously close to shuttering the company, reaching a point where she had just $411 in the bank.

A single moment gave her the fortitude to keep going, however:

I was taking every order that would possibly come in. Even if it was midnight, I didn’t care.

As I was walking to my car one night with a delivery of three arrangements, a couple of women stopped me and were like, “Oh my gosh, is that Farmgirl Flowers?” They recognized the burlap wrap that I created.

The fact that these women on the street recognized the brand I was trying to create and identified it as Farmgirl, I felt like, “Oh my gosh. I’m going to make it. Even though I only have $400 in the bank I’m going to make it. People recognize our product now.”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Farmgirl Flowers is on track to make $11 million this year, but two years ago, Christina was again panicked that the company wouldn’t make it:

I started to see a lot of companies that looked eerily similar to us pop up.

I was pretty convinced we were going to be out of business within a year because everywhere I looked there was a lot of consumer confusion or people were asking if we were the other companies now with our burlap-wrapped bouquets.

I thought all of these are raising $5 million, $10 million, $15 million pre-revenue. Here is my brilliant idea and now all these guys from tech companies are quitting their jobs and starting these companies that look like Farmgirl. I was really scared that we were going to be the Friendster to their Facebook.

I thought I had to raise funding to compete with them, so I pitched to 26 companies here on Sand Hill Road in San Francisco and even Boston and New York. I was unsuccessful, so I felt like I failed my team.

Every networking event I would go to, the first, second or third question anybody would ask me is, “What round are you on? Who’s invested?” As soon as I would say, “We’re bootstrapped,” I would see their eyes go over my shoulder and look for someone more valuable to talk to.

It was really frustrating and demoralizing.

Then I took a step back and realized I had equated my success and my company’s success with funding. I realized that my benchmark for success should be, “Am I creating a company that I’d want to work for, that I’d want to sell to and that I would want to buy from?” If I can do those things, then that’s success.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Listen to my full interviews with Jacqueline and Christina by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here (And download any of the past shows here.)

Coming up next on the blog: Dan Miller, co-founder of Level; and Brian Zuercher, founder of Seen

Tune in Thursday at 1 pm PT, 4 pm ET on Sirius XM Channel 111 to hear these upcoming guests on Entrepreneurs are Everywhere:

Oct. 6 : David Taylor, founder of Crudefunders; and Bill Keenan, chairman and CEO of Pango Financial

Oct. 13 : George Zimmer, founder of Men’s Wearhouse and now founder, chairman and CEO of Generation Tux; and Scott Adams, creator of Dilbert

Filed under: Customer Development

October 6, 2016

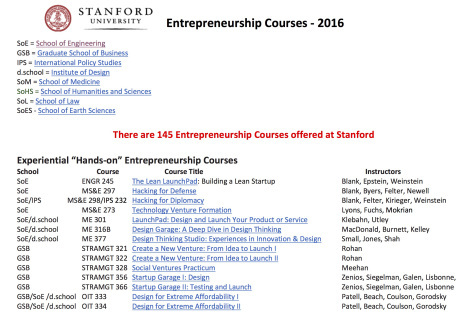

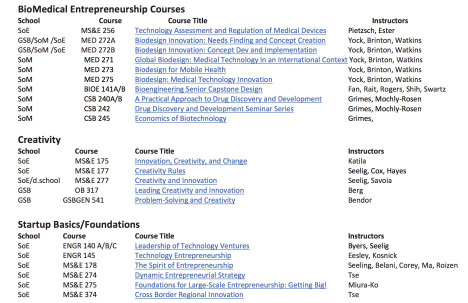

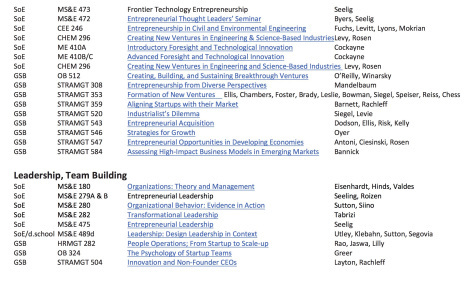

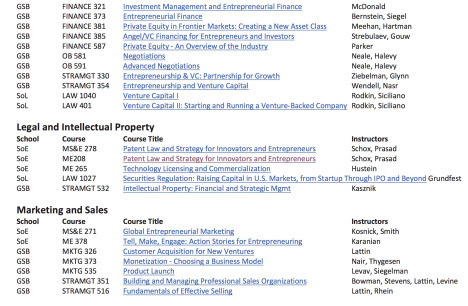

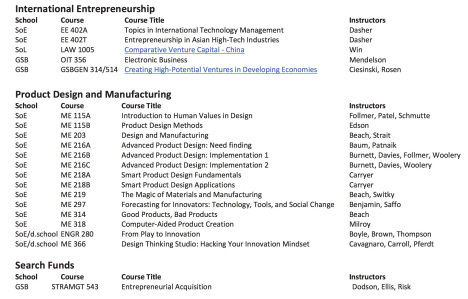

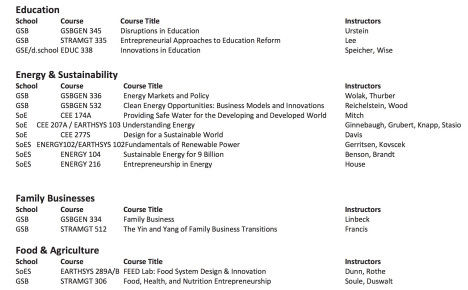

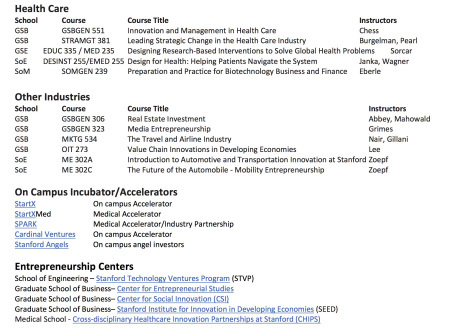

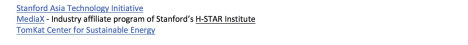

There are 145 Entrepreneurship Courses at Stanford

Stanford is an incubator with dorms

Download the full text file with links to the courses here.

Filed under: Hacking For Defense, Hacking for Diplomacy, Lean LaunchPad, Teaching

October 3, 2016

Entrepreneurs are Everywhere Show No. 43: Dakin Sloss and Ajeet Singh

In large companies innovators have to work twice as hard – they spend time fighting the system. In a startup, your ideas turn into reality really, really fast.

A startup founder needs to never lose sight of the vision, but be extremely adaptable to pretty much everything else.

Lots of people have visions. Most are hallucinations.

In a startup, you don’t fight the system; you are the system.

And realizing your vision as a founder takes equal parts determination and flexibility.

How startup ideas are conceived and nurtured was the focus of the guests on today’s Entrepreneurs are Everywhere radio show.

The show follows the journeys of founders who share what it takes to build a startup – from restaurants to rocket scientists, to online gifts to online groceries and more. The program examines the DNA of entrepreneurs: what makes them tick, how they came up with their ideas; and explores the habits that make them successful, and the highs and lows that pushed them forward.

Dakin Sloss

Joining me in the Stanford University studio were

Dakin Sloss, co-founder of Tachyus, which offers predictive analytics and quantitative optimization for the petroleum industry

Ajeet Singh, co-founder of ThoughtSpot, provider of search-driven analytics

Ajeet Singh

Listen to my full interviews with Dakin and Ajeet by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here

(And download any of the past shows here.)

Clips from their interviews are below.

Dakin Sloss co-founded Tachyus, providing predictive analytics and quantitative optimization for the petroleum industry, in 2013.

Prior to Tachyus, Dakin co-founded OpenGov, a platform to share, visualize, and analyze government financial data. Before OpenGov, he built California Common Sense, the open data and government watchdog non-profit.

Dakin was recognized as one of the Forbes 30 Under 30 in 2016.

While building OpenGov, Dakin learned that founders must maintain the vision for their startup idea while being flexible about how best to achieve it:

Lots of people have visions. Not as many people can figure out how to make them happen.

One of the hardest parts about starting something is being very firm in your big picture vision, and being extremely adaptable to pretty much everything else.

For example, customers usually have a good intuitive understanding of the problem they have. But they can struggle with communicating exactly what that problem is and exactly what solution they’d like. Your job is to help them figure that out.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Ajeet Singh is co-founder and CEO at ThoughtSpot.

Prior to starting ThoughtSpot, Ajeet was co-founder and Chief Products Officer at Nutanix, an enterprise data storage industry. Ajeet learned the ropes of enterprise startups at Aster Data Systems, where he was Senior Director of Product Management.

Prior to Aster, Ajeet worked at Oracle where he was part of the team that first launched Oracle Database to the Amazon EC2 cloud.

Leaving a big company like Oracle to work at a startup was an eye-opener for Ajeet:

In a large company, you come up with new ideas but then you are mostly fighting the system. When you move from a large company to a small company, your ideas turn into reality really, really fast.

Once you realize that your ideas will get implemented very quickly, you think, ‘I’m the only one watching,’ so the bar for your idea actually goes up. You have to make sure that you looked through all the implications of what you are suggesting. Ideas have to be that much higher quality because there are not too many people watching.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

—

One of the things Dakin struggled with at OpenGov was how important it is to get team communication right. Being the smartest person in the room doesn’t always mean you’re the most effective, he said:

We made so many silly communication mistakes – like we weren’t doing consistent one-on-ones and we weren’t facilitating good communication across the team. We were growing really fast and we would deal with issues as they came up, rather than proactively making sure everyone was working really well together.

So much of building a company is about people, independent of the particular subject that you’re focusing on, and so much is about setting things up for it to be a great environment for people to collaborate, to trust each other. A lot of small things – things like how you set up meetings, and how you schedule out your week – have big, cascading consequences. If you get them right, things are really smooth. If you get them a little bit off, you have a lot to fix.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Here’s how he makes sure the Tachyus team works well together:

Companies really thrive on rhythms in the same way that people, or families, or relationships do. So we dedicate the beginning of each of our week to our leadership team meetings and then an “all hands” meeting. These seem like small things, but they turn out to be really important, because as you’re pivoting, changing your business model and changing your product, there need to be some things that are stable to keep people on the same page.

The really the big advantage you have as a small company, is that you can get a lot of things wrong but as long as you get people around the table that are flexible, are good communicators, and are smart, you’re going to be able to figure a lot of things out. You may be in the wrong market at first. You may be in the wrong product at first. The key is getting your organization set up to be adaptable.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Having the opportunity to make a difference in the world drives Dakin, and so does working with like-minded people

Part of what’s fun about building a company is bringing together people that have a shared thesis or shared world view. There are obviously lots of differences, but creating an environment in which those people thrive and can collaborate together, it’s a new type of community basically.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

—

Rather than put work into creating a new markets for his business ideas, Ajeet looks for business opportunities in existing markets. He explains:

What I am excited about is opportunities in very large markets with multiple multibillion dollar exits and where the technology has become old.

The most important thing is to come up with an idea that solves a big problem. Your solution has to be 10x to 100x better, compared to what is out there. People already have an existing way of solving the same problem.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

At Aster Data Systems, Ajeet and his team ran into challenges trying to transition their product to mainstream customers:

We had a lot of success working with large web companies. Companies like MySpace and LinkedIn became some of our biggest customers. We tried to sell inside Silicon Valley, so these were all tech companies. We were mostly selling our product to engineers.

As we tried to sell outside the Valley, it is a very different world. Selling to an IT person or businessperson in the middle of Chicago is very different from selling to a LinkedIn engineer.

We struggled with our messaging, how we positioned our product to companies that were in the Valley versus outside.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

He carried the customer lessons with him to Nutanix and it paid off:

At Nutanix, most of our early customers were on the East Coast. We learned that if you are building a product for enterprises, start with the East Coast. You can scale much better. Your learning will be much, much better.

There are 500 Fortune 500 companies and there are global 2000, and there are another maybe 1 million small and medium businesses in the world. A lot of them do not have the engineering talent that companies in the Valley do.

So if you’re building a product, you’ve got to build it, test it, position it for the large market and the large market is not the Valley – unless you are building technology for developers, then Silicon Valley is a great place to do that.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Ajeet added that Silicon Valley’s unique startup ecosystem offers founders a chance to do things they could never do elsewhere in the world:

There is no place like this anywhere else. When it comes to cultural diversity, the freedom to express yourself, the freedom to fail, being able to talk about your failures with pride, these kinds of things just don’t exist anywhere else in the world.

You can go to a coffee shop and run in to a billionaire. If they have been successful, they want to give back and they are very open about giving you their time.

I have been really fortunate to have some really good mentors and advisers over the years from whom I have learned a lot.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Listen to my full interviews with Dakin and Ajeet by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here. (And download any of the past shows here.)

Coming up next on the blog: Jackie Ros , founder of Revolar ; and Christina Stembel , founder of Farm Girl Flowers

Tune in Thursday at 1 pm PT, 4 pm ET on Sirius XM Channel 111 to hear these upcoming guests on Entrepreneurs are Everywhere:

Sept. 29 : Julie Cottineau, founder and CEO of BrandTwist; and Rich Fulop, co-founder of Brooklinen

Oct. 6 : David Taylor, founder of Crudefunders; and Bill Keenan, chairman and CEO of Pango Financial

Oct. 13 : George Zimmer, founder of Men’s Wearhouse and now founder, chairman and CEO of Generation Tux; and Scott Adams, creator of Dilbert

Filed under: Customer Development

September 27, 2016

Entrepreneurs are Everywhere Show No. 42: Tina Fitch and Alice Brooks

The more that people pay you, the more influence customers feel they should have, but they don’t necessarily know what they want.

Customers will try to be polite and tell you want you want to hear. We had to figure out how to get honest feedback.

Doing customer discovery isn’t the same as running a focus group. And customers don’t always know the best way to solve a problem or fill a need they have.

How entrepreneurs gather, understand and use customer feedback to improve their products was the focus of the guests on today’s Entrepreneurs are Everywhere radio show.

The show follows the journeys of founders who share what it takes to build a startup – from restaurants to rocket scientists, to online gifts to online groceries and more. The program examines the DNA of entrepreneurs: what makes them tick, how they came up with their ideas; and explores the habits that make them successful, and the highs and lows that pushed them forward.

Tina Fitch

Joining me in the Stanford University studio were

Tina Fitch, co-founder of Hobnob, an app that lets users send and manage event invitations via text message

Alice Brooks, co-founder of Roominate, toys meant to promote girls’ interest in science, tech and engineering

Alice Brooks

Listen to my full interviews with Tina and Alice by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here

(And download any of the past shows here.)

Clips from their interviews are below.

Tina Fitch thrives on building products that enable real-world experiences. Before co-founding Hobnob , she founded Switchfly, a SaaS platform that continues to work with airlines, hotel chains, payment companies, and loyalty programs in. She returned to her home state of Hawaii to become a mentor and advisor to tech accelerators and startups, and a parent of two before launching Hobnob.

In both of her startups, Tina did a lot of customer discovery to understand customer problems and see if her products offered the right solution. Here’s what she learned about managing customer feedback:

When you sell into the enterprise, there’s a very fine line between making your customers happy and potentially having them influence the product a little bit too heavily.

You have to have conviction in your product to balance making them happy, but not necessarily changing your entire product priorities based on what they think they currently need.

The more that people pay you, the more influence they feel they should have, but they don’t necessarily know what solution they want.

You have to have enough conviction in your own vision of how you’re going to solve that problem for them to be able to take all those data points and feedback they gave you, then make a better solution for them.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Alice Brooks is the co-founder of Roominate . She grew up playing in her dad’s robotics lab and made her first toy when she was 8 years old using a saw she received for Christmas instead of the Barbie she asked for.

Alice graduated from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with a B.S. in mechanical engineering and holds a master’s in mechanical engineering from Stanford.

With Roominate, Alice wanted to build a toy that would encourage girls to explore science, technology and engineering. She and her co-founder, Bettina Chen, didn’t have kids of their own, so before designing the product, they did a lot of user testing:

We went out into people’s homes and watched girls play with their favorite toys and asked what they liked about them, what they didn’t like. We saw a lot of dolls – Barbies, American Girl dolls – and we saw a lot of doll houses.

We brought some building toys with us to see how girls would interact. We found they liked that just as much, but it was all about the story they were telling around them and the context that they put it in.

With Roominate, we give them the context of ‘this is what you can with your dolls in.’ Introducing it that way first opened the door. All of a sudden they wanted to build and add more circuits.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

During customer discovery, Alice learned a critical lesson about gathering customer feedback:

Customers will try to be polite to you and tell you want you want to hear.

We did a testing session with a group of girls where we had to make this spinning-disco-ball-dance party. We were trying to use circuits and build together in some way. They all seem like they really like it. They were dancing to Rihanna with it.

The next day, their dad calls us up, and says, “Kate didn’t want to upset you, but she told me it was very stupid. She asked me not to tell you.”

That’s how we started figuring out ways to get more honest feedback, always following up with the parents the next day.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

—

Tina explained what’s different about starting up a second time:

I remember reading various business books or reading about different entrepreneurial journeys, and I thought at that time probably arrogantly that, oh, I’m never going to make those types of mistakes, I’m too smart for that. And I probably, the first time around, made every single one of them, everything from challenges with co-founders or investors or board members or clients.

The second time around, I not only have the confidence of experience, but I also have the confidence in my own instincts.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

In her first startup, she quickly learned that everyone has suggestions and advice for how to do things, but that a founder must stand up for their vision:

It’s important to take data points and advice from people, whether they’re your peers, advisors or your board members. But ultimately, you’re going to have to bear the weight of your decision and you can’t point a finger at anyone else.

You have to have that courage of conviction of your own instincts and believe wholeheartedly at your core that what you’re doing is the right thing.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Having now done two startups, Tina is struck by the different leadership skills needed to build and manage a company:

All the skills that get you to a position where you’re building something and going against the grain – the competitiveness, the aggressiveness, almost like the Darwinistic approach to success – are different from the skills you need to run a company.

As manager, you really have to shift gears and become more of a communicator. You have to have empathy for your team and learn how to get the best performance out of people.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

She was also surprised to find that being a founder can be isolating:

When you’re a founder of a company, it becomes almost part of your very being.

Bearing that responsibility day in and day out and feeling the weight of ownership over not only a product, but your team and their welfare and your community of users and their happiness becomes a very hard and lonely experience a lot of times.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

—

Alice and her team made it point to not just get customer insights but to understand all aspects of their business model.

That included getting first-hand knowledge of how their manufacturers operate:

We spent two weeks in China getting to know our manufacturers face-to-face and understanding what it would take to build this product; what trade-offs we needed to make; and what we could do now, what other opportunities there were.

It was beyond helpful. When we first started setting up our manufacturing, we were using a go-between, and we didn’t understand what was really happening.

Once we got there, walked the factory and saw all the different machines they had, we got to know our manufacturer, how they do business. It was really helpful not just for that first launch, but as we grew the company and as we tried to expand knowing how business was done over there.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Once they found product-market fit, they launched quickly.

We had a prototype version so you could get the idea. We had to work very quickly to then make it a real product, and we did. From the start of our Kickstarter to when we actually shipped to customers was less than seven months. It was a very quick turnaround, which often doesn’t happen these days with companies.

We didn’t have any funding. We didn’t have any money ourselves to spend, so we didn’t do any kind of hype around the launch. It was all just people that we’d met and tested with that were excited about the idea and shared it out to people. I don’t know if that would work now.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

As a first-time founder, Alice had a steep learning curve. Her advice for other first-time founders is be prepared to work hard:

It gets to be more and more work as you go.

There’s this image when you’re a student thinking about being an entrepreneur that it’s going to be really glamorous and you’re going to do your product and raise a bunch of funding and then you’re going to be set. The reality is the more you do, the higher the stakes become. You become responsible to a lot of different stakeholders.

The exciting part is you can actually get your ideas and your designs out there into real people’s hands so much faster than you could by going a different route.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Listen to my full interviews with Tina and Alice by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here (And download any of the past shows here.)

Coming up next on the blog: Dakin Sloss , founder of Tachyus ; and Ajeet Singh , co-founder of ThoughtSpot .

Tune in Thursday at 1 pm PT, 4 pm ET on Sirius XM Channel 111 to hear these upcoming guests on Entrepreneurs are Everywhere :

Sept. 22 : Siggi Hilmarrson, founder and CEO of Siggi’s Dairy; and Jonathan Hirsch, founder and president of Syapse

Sept. 29 : Julie Cottineau, founder and CEO of BrandTwist; and Rich Fulop, co-founder of Brooklinen

Oct. 6 : David Taylor, founder of Crudefunders; and Bill Keenan, chairman and CEO of Pango Financial

Oct. 13 : George Zimmer, founder of Men’s Wearhouse and now founder, chairman and CEO of Generation Tux; and Scott Adams, creator of Dilbert

Filed under: Customer Development, SiriusXM Radio Show

September 25, 2016

7 Steps to Hacking for Defense

September 19, 2016

The Innovation Insurgency Scales – Hacking For Defense (H4D)

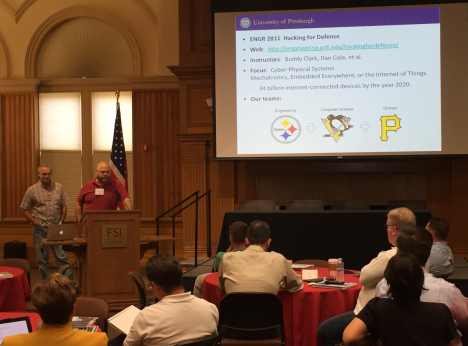

Hacking for Defense is a battle-tested problem-solving methodology that runs at Silicon Valley speed. We just held our first Hacking for Defense Educators Class with 75 attendees.

The results: 13 Universities will offer the course in the next year, government sponsors committed to keep sending hard problems to the course, the Department of Defense is expanding their use of H4D to include a classified version, and corporate partners are expanding their efforts to support the course and to create their own internal H4D courses.

The results: 13 Universities will offer the course in the next year, government sponsors committed to keep sending hard problems to the course, the Department of Defense is expanding their use of H4D to include a classified version, and corporate partners are expanding their efforts to support the course and to create their own internal H4D courses.

It was a good three days.

————-

Another Tool for Defense Innovation

Last week we held our first 3-day Hacking for Defense Educator and Sponsor Class. Our goal in this class was to:

Train other educators on how to teach the class at their schools.

Teach Department of Defense /Intelligence Community sponsors how to deliver problems to these schools and how to get the most out of student teams.

Create a national network of colleges and universities that use the Hacking for Defense Course to provide hundreds of solutions to critical national security problems every year.

What our sponsors have recognized is that Hacking for Defense is a new tool in the country’s Defense Innovation toolkit. In 1957 after the Soviet Union launched the Sputnik satellite the U.S. felt that it was the victim of a strategic technological surprise. DARPA was founded in 1958 to ensure that from then on the United States would be the initiator of technological surprises. It does so by funding research that promises the Department of Defense transformational change instead of incremental advances.

By the end of the 20th century the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) realized that it was no longer the technology leader it had been when it developed the U-2, SR-71, and CORONA reconnaissance programs in the 1950’s and 1960’s. Its systems were struggling to manage the rapidly increasing torrent of information being collected. They realized that commercial applications of technology were often more advanced than those used internally. The CIA set up In-Q-Tel to be the venture capital arm of the intelligence community to speed the insertion of technologies. In-Q-Tel invests in startups developing technologies that provide ready-soon innovation (within 36 months) vital to the IC mission. More than 70 percent of the In-Q-Tel portfolio companies have never before done business with the government .

By the end of the 20th century the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) realized that it was no longer the technology leader it had been when it developed the U-2, SR-71, and CORONA reconnaissance programs in the 1950’s and 1960’s. Its systems were struggling to manage the rapidly increasing torrent of information being collected. They realized that commercial applications of technology were often more advanced than those used internally. The CIA set up In-Q-Tel to be the venture capital arm of the intelligence community to speed the insertion of technologies. In-Q-Tel invests in startups developing technologies that provide ready-soon innovation (within 36 months) vital to the IC mission. More than 70 percent of the In-Q-Tel portfolio companies have never before done business with the government .

In the 21st century the DOD/IC community have realized that adversaries are moving at a speed that our traditional acquisition systems could not keep up with. Hacking for Defense combines the rapid problem sourcing and curation methodology developed on the battlefields in Afghanistan and Iraq by Colonel Pete Newell and the US Army’s Rapid Equipping Force with the Lean Startup practices that I pioneered in Silicon Valley and which are now the mainstay of the National Science Foundations’ I-Corps program. Hacking for Defense is a problem-solving methodology that offers the DOD/IC community a collaborative approach to innovation that provides ready-now innovation (within 12-36 months).

Train the Trainers

Pete Newell, Joe Felter and I learned a lot developing the Hacking for Defense class, more as we taught it, and even more as we worked with the problem sponsors in the DOD/Intel community. Since one of our goals is to make this class available nationally, now it was time to pass on what we had learned and to train other educators how to teach the class and sponsors how to craft problems that student teams could work on.

Since one of our goals is to make this class available nationally, now it was time to pass on what we had learned and to train other educators how to teach the class and sponsors how to craft problems that student teams could work on.

(If you want a great overview of the Hacking for Defense class, stop and read this article from War on The Rocks. Seriously.)

When we developed our Hacking for Defense class, we created a ton of course materials (syllabus, slides, videos). In addition, for the Educator Class we captured all we knew about setting up and teaching the class and wrote a 290-page educator’s guide with suggested best practices, sample lesson plans, and detailed lecture scripts and slides for each class session. We developed a separate sponsor guide with ideas about how to get the most out of the student teams and the university.

When we developed our Hacking for Defense class, we created a ton of course materials (syllabus, slides, videos). In addition, for the Educator Class we captured all we knew about setting up and teaching the class and wrote a 290-page educator’s guide with suggested best practices, sample lesson plans, and detailed lecture scripts and slides for each class session. We developed a separate sponsor guide with ideas about how to get the most out of the student teams and the university.

The Educator Class: What We Learned

One of the surprises for me was seeing the value of having the Department of Defense and other government agency sponsors working together with the university educators. (One bit of learning was that the sponsors portion of the workshop could have been a day shorter.)

Two other things we learned has us modifying the pedagogy of the class.

First, our mantra to the students has been to learn about “Deployment not Demos.” That meant we were asking the students to understand all parts of the mission model canvas, not just the beneficiaries and the value proposition. We wanted them to learn what it takes to get their product/service deployed to the field, not just have another demo to a general. This meant that the minimal viable products the students built were focused on maximizing their learning of what to build, not just building prototypes. While that worked great for the students, we learned from our sponsors that for some them getting to deployment actually required demos as part of the means to reach this end. They wanted the students to start delivering MVPs early and often and use the sponsor feedback to accelerate their learning.

This conversation made us realize that we had skewed the class to maximize student learning without really appreciating what specific deliverables would make the sponsors feel that the time they’ve invested in the class was worthwhile. So for our next round of classes we will:

require sponsors to specifically define what success from their student team would look like

have students in the first week of class present what sponsors say success looks like

still encourage MVPs that maximize student learning, but also recognize that for some sponsors, learning could be accelerated with earlier functional MVPs

Our second insight that has changed the pedagogy also came from our sponsors. As most of our students have no military experience, we teach a 3-hour introduction to the DOD and Intel Community workshop. While that provides a 30,000-foot overview, it doesn’t describe any detail about the teams’ specific sponsoring organization (NSA, ARCYBER, 7th Fleet, etc.). (By the end of the quarter every team figures out how their sponsor ecosystem works.) The sponsors suggested that they offer a workshop early in the class and brief their student team on their organizations, budget, issues, etc. We thought this was a great idea as this will greatly accelerate how teams target their customer discovery. When we update the sponsor guide, we will suggest this to all sponsors.

Our second insight that has changed the pedagogy also came from our sponsors. As most of our students have no military experience, we teach a 3-hour introduction to the DOD and Intel Community workshop. While that provides a 30,000-foot overview, it doesn’t describe any detail about the teams’ specific sponsoring organization (NSA, ARCYBER, 7th Fleet, etc.). (By the end of the quarter every team figures out how their sponsor ecosystem works.) The sponsors suggested that they offer a workshop early in the class and brief their student team on their organizations, budget, issues, etc. We thought this was a great idea as this will greatly accelerate how teams target their customer discovery. When we update the sponsor guide, we will suggest this to all sponsors.

Another surprise was how applicable the “Hacking for…” methodology is for other problems. Working with the State Department we are offering a Hacking for Diplomacy class at Stanford starting later this month. And we now have lots of interest from organizations that have realized that this problem-solving methodology is equally applicable to solving public safety, policy, community and social issues internationally and within our own communities. We’ll soon launch a series of new modules to address these deserving communities.

Lessons Learned

Hacking for Defense = problem-solving methodology for innovation insurgents inside the DOD/Intel Community

The program will scale to 13+ universities in 2017

There is demand to apply the problem-solving methodology to a range of public sector organizations where success is measured by impact and mission achievement versus revenue and profit.

Filed under: Hacking For Defense, Hacking for Diplomacy, Science and Industrial Policy

September 15, 2016

Entrepreneurs are Everywhere Show No. 41: Chris Schroeder and Andy Cunningham

There are only two emotions in startups — utter ebullient enthusiasm and outright terror.

Here’s the big thing about tech companies: They all believe that if they build it, the world will come, but it doesn’t really work that way.

The reality distortion you create is imperative to be able to believe what you’re doing, and get the people around you to believe what you’re doing. But you must find ways to check those realities.

A founder’s conviction will help get a startup off the ground. Hubris can kill it.

Why it’s important for entrepreneurs to temper confidence with regular reality checks was the focus of the guests on today’s Entrepreneurs are Everywhere radio show.

The show follows the journeys of founders who share what it takes to build a startup – from restaurants to rocket scientists, to online gifts to online groceries and more. The program examines the DNA of entrepreneurs: what makes them tick, how they came up with their ideas; and explores the habits that make them successful, and the highs and lows that pushed them forward.

Chris Schroeder

Joining me in the Stanford University studio were

Chris Schroeder, Internet/media CEO, venture investor and author of Startup Rising: The Entrepreneurial Revolution Remaking the Middle East

Andy Cunningham, founder and CEO of Cunningham Collective

Andy Cunningham

Listen to my full interviews with Chris and Andy by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here

(And download any of the past shows here.)

Clips from their interviews are below.

Chris Schroeder is an American entrepreneur, advisor and investor in interactive technologies and social communications.

He wrote the first book on startups in the Arab World, Startup Rising: The Entrepreneurial Revolution Remaking the Middle East, and was previously the CEO and Publisher of washingtonpost.newsweek interactive and co-founder of HealthCentral.com , sold in 2012.

In his work with startups, Chris notices that founders tend to think investors hold some magic key to their success. He reminds them to look to themselves:

Don’t be in awe of money. I think across the board, young people think that if all that happens, if Sequoia invested in my company, everything will get taken care of.

First of all, most of your customers don’t know or care who any of these venture firms are.

Second, the individuals who invest in you are invariably more important than the venture firms themselves. For customers t he venture firm brands don’t matter. For you and your startup it’s the individuals inside those firms who will either make your life miserable or who really understand what it takes to help you build your company. It’s your company. You are the entrepreneur.

Just because someone happens to have access to wealth, more often than not, they haven’t done what you’ve done. They don’t know what you do.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

And while believing in oneself is critical, it’s equally important for a founder to validate his vision, he says:

You create a reality distortion field, and the power of your narrative is to be able to believe what you’re doing, get the people around you to believe what you’re doing, and to get employees passionately dedicated to work it.

But there’s a very fine line between believing your own spin and taking a dispassionate views of what you’re doing and not getting lost in your own narratives.

You must find ways –without getting caught in 360 degrees of advice– to check those realities, because you can get trapped by naysayers who say it can’t happen or it’s a bad idea. But on the other hand, you can believe in things so deeply and just sort of get trapped in believing in your own idea.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Andy Cunningham is the founder and president of Cunningham Collective, a brand strategy firm dedicated to bringing innovation to market.

Andy came to Silicon Valley in 1983 to work for Regis McKenna and help Steve Jobs launch the Macintosh. When Steve left Apple to form NeXT, he chose Cunningham Communication to represent him. Andy continued to work with Steve for several years and has developed marketing, branding and communication strategies for game-changing technologies and companies ever since.

An entrepreneur at the forefront of marketing, branding, positioning and communicating “The Next Big Thing,” she has played a key role in the launch of a number of new categories including video games; personal computers; desktop publishing; digital imaging; RISC microprocessors; software as a service; very light jets; and clean tech investing. She is an expert in creating and executing marketing, branding and communication strategies that accelerate growth, increase shareholder value and advance corporate reputation.

Andy says world-class founders exude confidence and refuse to listen to the naysayers:

You have to believe in yourself and realize that it’s lonely at the top. If you can live with being lonely and if you can believe in yourself, then just go for it.

Be crazy, be wild, just go for it and don’t listen to anybody telling you that it can’t be done.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

However, to be successful, founders must be more than confident and passionate, she says:

Here’s the big thing about tech companies: They all believe that if they build it, the world will come.

You have to believe that because it’s all about believing in yourself, but it doesn’t really work that way. That’s where marketing comes into play.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

—

Chris said the hardest thing about doing an internal startup at the Washington Post was to convince others in the company to share his vision for the new interactive product:

I probably spent 30 percent of my time in shuttle diplomacy between departments inside the Washington Post, convincing them that if we did not leap into the future, the future would be would be taken from us.

The good news was that you had amazing clay to play with – amazing content, amazing journalists and journalism – and you could rethink worlds powerfully.

The down side of it was a lot of the legacy businesses at the Washington Post, particularly on the business side, didn’t understand the interactive and online business and felt threatened by us.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Keeping the interactive unit separate from the rest of the company helped, he said. But he wonders if the company could have made a bigger move:

They were very smart to break us off. We were a separate company completely, reporting to the Board in a separate physical space and for a time, to give us cover, I think that was important – at first.

What ended up happening, however, was we were eventually subsumed under the traditional media business. I think the one audacious step would have been the reverse that, have the print people working for the interactive people. At the end that what’s happening to journalism and the Washington Post.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Here’s how Chris compares his intrapreneurial experience at the Washington Post with what it was like to do a startup:

There are only two emotions in startups — utter ebullient enthusiasm and outright terror.

The good news is that when I was doing HealthCentral, I didn’t have to ask anybody’s explanation for anything, I didn’t have to worry about newspaper circulation being affected as I did in the intrapreneurial experience I had at the Washington Post.

The bad news is that as a startup founder you have no brand, you have no balance sheet, you have investors behind you, you have employees that you’re responsible for, you have an impact you’re trying to make on people’s lives while building a business. Every day was a sine wave of highs and lows of figuring that out.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

—

Andy explained that, years ago, a PR person’s was to turn so-called influencers like journalists and analysts into advocates for your client. That goal hasn’t changed, but the playing field has:

What I do today is what I really did in the old days, which is to make sure that the story is differentiated and compelling.

When there was only a small number of influencers, it was a little bit easier to do. Now today, there are zillions of influencers and they don’t have to be anyone famous. They can just be somebody who writes a blog.

With social media and with bloggers and with the cable TV and all the different networks that you can get on television and radio like this, everybody you look at is an influencer now. It’s a lot harder to target it.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

The way to get influencers’ attention is to show how you’re different from everyone else. This is called positioning and it’s different from marketing. Here’s how Andy did explained it to a client:

I reverse-engineered the process that I’d been going through for decades and out of all the hundreds and hundreds of companies I’d worked with, there was really only three types of companies.

First, there are product-oriented companies, like Microsoft or Oracle;

Second, there are customer-oriented companies like Zappos or Airbnb; and

Third, there are concept-oriented companies like Apple was in the early days.

I gave product-oriented companies the nickname of mechanics, I gave customer-oriented companies the nickname of mothers and I gave concept-oriented companies the nickname of missionaries.

In the end, it’s about how you tell the story, and the center of that story has to be a differentiated statement about your role and your relevance in the market.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Positioning must be authentic, she stresses:

Here’s the thing about great positioning or great PR: You have to be aligned with who you are.

It’s like I can’t go out into the marketplace and convince people that I am a blonde ballerina. I’m not blonde and clearly I’m no ballerina. Because my DNA tells me I’m really more like a racquetball player I can’t pretend to be a ballerina for very long before I get found out.

The same is true with companies. If you’re a product-oriented company and you want to be a missionary — which many of them do, in a very short amount of time the marketplace will find out you’re not authentic.

You have to align who you are, your DNA, with how you position yourself in the marketplace.

If you can’t hear the clip, click

Listen to my full interviews with Chris and Andy by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here. (And download any of the past shows here.)

Next on Entrepreneurs are Everywhere : Sunny Shah , assistant director of the Engineering, Science & Technology Entrepreneurship Excellence Master’s Program at the University of Notre Dame and Curt Haselton , co-founder of the Haselton Baker Risk Group .

Tune in Thursday at 1 pm PT, 4 pm ET on Sirius XM Channel 111.

Want to be a guest on the show? Entrepreneurship stretches from Main Street to Silicon Valley, from startups to big companies. Send an email to terri@kandsranch.com describing your entrepreneurial journey.

Filed under: Customer Development

September 10, 2016

Entrepreneurs are Everywhere Show No. 42: Sunny Shah and Curt Haselton

We as researchers go in with a bias – that obviously these guys want our technology – but that is not the case for a lot of customers. What you think about your technology is great, but at the end of the day you’re not the one buying it.

It was intimidating from day one. I am good with doing research and doing experiments but talking to customers is not my forte.

Scientific research it is hypothesis-driven. You’re just guessing and then trying to prove it true or false. This whole commercialization side of things is not that much different

For scientific researchers who want to commercialize their technology, doing a startup first pulls them out of their comfort zone. But then the Lean Startup’s scientific method of validating their business idea quickly has them feeling right at home.

What it’s like to go from the comfort of the lab bench to the chaos of a startup was the focus of the guests on today’s Entrepreneurs are Everywhere radio show.

The show follows the journeys of founders who share what it takes to build a startup – from restaurants to rocket scientists, to online gifts to online groceries and more. The program examines the DNA of entrepreneurs: what makes them tick, how they came up with their ideas; and explores the habits that make them successful, and the highs and lows that pushed them forward.

Sunny Shah

Joining me in the Stanford University studio were

Sunny Shah, assistant director and faculty of the ESTEEM Graduate Program at the University of Notre Dame

Curt Haselton, co-founder and CEO of Haselton Baker Risk Group

Curt Haselton

Listen to my full interviews with Sunny and Curt by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here.

(And download any of the past shows here.)

Clips from their interviews are below.

Sunny Shah is an Assistant Director for the ESTEEM Graduate Program at the University of Notre Dame. In addition he conducts research with Dr. Hsueh Chia Chang in Chemical Engineering. Sunny received his Ph.D. from University of California, Davis in Biomedical Engineering. For his doctoral work, his research focused on liver tissue engineering and stem cell differentiation.

Sunny’s startup idea emerged from a diagnostic tool he’d developed in his lab to detect pathogens. He thought it might have an application in the food service industry and so leapt at the chance to join the National Science Foundation Innovation Corps.

He was initially overwhelmed:

It was intimidating from day one. I was out of my comfort zone. I am good with doing research and doing experiments but here there are these four teaching faculty trying to infuse into us to find the need and then see if your problem fits the need.

The only way to do that is by going out and talking to the customers who would eventually buy this. We’re used to just talking to scientists, but here they were asking us in six weeks to do a 100 interviews. Not on the phone, not over Skype but in-person interviews with potential customers.

I’ve never talked to people at food processing plants and meat processing plants.

On our flight back from the workshop, I was trying to come up with excuses to drop out of the program. I thought, ‘This is not something I signed up for. I’m interested in the commercialization side but this fast-paced talking to the customers is not my forte.’

But we stuck with it. We found people to talk to through Google searches. We went to the USDA list and found whatever meat processing plants they inspect and food processing plants they inspect, and went from there.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Once he found customers, he had to speak with them. Here’s what he did, and why he had a change of heart about I-Corps that marked a career pivot for him:

I started not even cold calling; it was cold showing up. There were a couple streets, the meat district of Chicago, and I just started knocking on doors.

I was afraid these guys weren’t going to understand what I was doing but it turned out that once you get in the door and start talking to them about how they do testing for pathogens right now, that’s when you saw them open up.

That’s when I realized that this is something I can do because even though it is uncomfortable for me, they are very interested in talking, they just want a sounding board and that’s what I wanted to be.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

I realized the importance of talking to customers, listening and learning from them. The more you talk to them you start seeing how painful it was for them.

They said, ‘We currently have detection techniques that take two days and while we wait for the results we have to store the food.’ What that meant was that until the test results came back the food can’t ship and that’s lost revenue for them. In talking about how expensive the costs of that two-day delay are for them we could start seeing that maybe our research could help these people.

For me, it was seeing not just what goes on the bench in our lab but there is some sort of real-world application for it.

And to hear it from these people who are not scientists, that was kind of cool.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Curt Hazleton is a leader in structural earthquake engineering, focusing on building code development, building collapse safety assessments, and earthquake damage loss estimation. He’s a co-founder and CEO of HB Risk, and a Professor and Department Chair in Civil Engineering at California State University, Chico. He received his Ph.D. in Structural Engineering from Stanford University in 2006. Among his awards, Curt received the 2013 Shah Family Innovation Prize from the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute, honoring an individual under the age of 35 for creativity, innovation and an entrepreneurial spirit in earthquake risk mitigation and management.

Like Sunny, Curt participated in the NSF I-Corps and quickly learned how illuminating customer interviews could be:

We were extremely surprised that by simply getting out of the building and using the customer discovery process you can go and interview people and they’ll tell you exactly what they need and what you can build for them and how much they’ll pay for it.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

In doing customer discovery, Curt and his co-founder started out with one customer in mind, but quickly found a more lucrative option:

We initially started with the structural engineers as our target market because that’s what we knew. That’s where we saw the initial need.

As we went through that it’s been verified that there is a market there and they’re interested, but we’ve also seen there’s another market that we call the risk-pricing market. Those are the people insuring the buildings and underwriting the mortgages for the buildings.

They care more. Engineers care about the design of the building, absolutely, but they’re not the ones with the money on the line.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Along the way, they met both skeptics and visionaries:

The difference between early adopters and mainstream people was very interesting, especially in the emerging market on the structural engineering side.

The early adopters would see the vision that we see. I was told by one of them it doesn’t even make sense that not everybody is adopting this right away today, because in five years everyone’s going to be doing it.

Then I’d go to people that I would characterize mainstream and they’d say, “Well, it doesn’t meet a need that we have right now.”

We had to take both pieces of feedback and realize it was an emerging market and not everyone would see the vision.

Since then, a few of those skeptic mainstream people have actually come back to us for licenses once they’ve had clients that want this done for them.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

—

Ultimately, Sunny and his co-founders killed their startup idea

We decided as a team that there was no match between what we’d learned in customer interviews about where the need was and what we were providing.

We decided we shouldn’t pursue this market.

It was tough at first but when you think about it, we saved time and money. That was the whole point of the exercise.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Today he teaches his students at Notre Dame how to use Lean Startup principles. He tells them:

Scientific research it is hypothesis-driven. You’re just guessing and then trying to prove it true or false. This whole commercialization side of things is not that much different. It’s a scientific method.

What you think about your technology is great, but at the end of the day you’re not the one who will be buying this, it will be the customers who will be buying this. The only way to know what they want is to get out of the building and talk to them.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Curt said the pace of startup life surprised him

I made more progress in the startup in the first four months than I did in the first four years as an academic chair.

That doesn’t mean we didn’t make progress in the department. We made a lot. It’s just a different nature. The startup pace has been a lot of fun.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Here’s his advice for other academics with tech ideas they’d like to commercialize:

Most researchers come at it with, “I have a product that I really love and I think someone should buy it from me,” and don’t come at it from, “There’s a need in the industry somewhere and I can create something to fill that need.”

Getting as quickly away from that first approach as possible would be my first recommendation, because in the Innovation Corps process we clearly saw that.

Most people said, “I have this great technology. I’ve never been out of my lab. I think someone will want to buy it from me,” but the commercial side of it wasn’t there.

You need to get at, “Does anyone care? Does anyone want to buy it?” as quickly as possible.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Listen to my full interviews with Sunny and Curt by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here. (And download any of the past shows here.)

Coming up next on the blog: Tina Fitch, co-founder and CEO of Hobnob; and Alice Brooks, co-founder and CEO Roominate

Tune in Thursday at 1 pm PT, 4 pm ET on Sirius XM Channel 111 to hear these upcoming guests on Entrepreneurs are Everywhere:

Sept. 22 : Siggi Hilmarrson, founder and CEO of Siggi’s Dairy; and Scott Adams, creator of Dilbert

Sept. 29 : Julie Cottineau, founder and CEO of BrandTwist; and Chase Jarvis, founder and CEO of Creative Live

Oct. 6 : Jonathan Hirsch, founder and president of Syapse; and George Zimmer, founder of Men’s Wearhouse and now founder, chairman and CEO of Generation Tux

Oct. 13 : David Taylor, founder of Crudefunders; and Bill Keenan, chairman and CEO of Pango Financial

Want to be a guest on the show? Entrepreneurship stretches from Main Street to Silicon Valley, from startups to big companies. Send an email to terri@kandsranch.com describing your entrepreneurial journey.

Filed under: Customer Development, SiriusXM Radio Show

September 7, 2016

Working Hard is not the same as working smart

Measuring how hard your team is working by counting the number of hours they work or what time they get in and leave is how amateurs run companies. The number of hours worked is not the same as how effective they (and you) are.

I had been invited by Rahul, one of my students from long ago, to stop in and see how his startup was doing. Actually startup would be a misnomer as Rahul had built a great company, now over $50M in annual revenue with hundreds of employees.

We were scheduled for dinner, but Rahul invited me over in the afternoon to sit in on a few of his staff meetings, get some product demos, admire the furniture and the café, and get a feel of the company.

Before we left for dinner I asked about the company culture and the transition from a startup to a company. We talked about how he was on-boarding new employees, managing scale by writing operations manuals for each job function, and publishing company and department mission and intent (he said he got the idea from reading my blog posts on mission and the one on innovation culture). It was all impressive – until we got on the subject of how hard his employees worked. His response reminded me what an idiot I had been for most of my career – “Our team knows this isn’t a 9-5 company. We stay as long as it takes to get the job done.” I looked a bit dumbfounded, which I think he took for impressed, because he continued, “most days when I leave at 7 pm my employees are still hard at work. They stay all hours of the night and we often have staff meetings on Saturdays.”

I cringed. Not because he was dumb but because for most of my career I was equally clueless about what was really happening. I had required the same pointless effort from my teams.

Our dinner was scheduled for 7:15 around the corner so we headed out at 7, announcing to his staff he was off to dinner. As soon as we got outside his building and into the full parking lot I asked Rahul if he could call the restaurant and tell them we were going to be late. I said, “Let’s just wait across the street from your company’s parking lot and watch the front door. I want to show you something I painfully learned way too late in my career.” He knew me well enough to patiently stand there. At 7:05, nothing happened. “What am I supposed to be seeing?” he asked. “Just wait,” I replied, hoping I was right. At 7:10 still no movement at the front door. By now he was getting annoyed, and just as he was about to say, “let’s go to dinner” the front door of the company opened – and a first trickle of employees left. I asked, “Are these your VPs and senior managers?” He nodded looking surprised and kept watching. Then after another 10-minute pause, a stream of employees poured out of the building like ants emptying the nest. Rahul’s jaw dropped and then tightened. Within a half-hour the parking lot was empty.

There wasn’t much conversation as we walked to dinner. After a few drinks he asked, “What the heck just happened?”

21st-Century Work Measured by 20th-Century Custom and Cultural Norms

In the 20th century we measured work done by the number of hours each employee logged. On an assembly line each employee was doing the same thing, so productivity simply equaled hours worked. Employees proved they were at work by using time cards to measure attendance. (Even today the U.S. government still measures its most creative people with a time-management system in 15-minute increments.)

Even as white collar (non-hourly) jobs proliferated, men (and the majority of workforce management was men) equated hours with output. This was perpetuated by managers and CEOs who had no other norms and never considered that managing this way was actually less effective than the alternatives.

I pointed out to Rahul that what he was watching was that his entire company had bought into the “culture of working late” – but not because they had work to do, or it was making them more competitive or generating more revenue, but because the CEO said it was what mattered. Every evening the VPs were waiting for the CEO to leave, and then when the VPs left everyone else would go home. Long hours don’t necessarily mean success. There are times when all-nighters are necessary (early days of a startup, on a project deadline) but good management is knowing when it is needed and when it is just theater.

Rahul’s response was one I expected, “This is what we did in investment banking at my first job in my 20s. And my boss rewarded me for my “hard work.” Sleeping at my desk was something to be proud of.”

I completely understood; I learned the same thing from my boss.

Productivity

The rest of the dinner conversation revolved around, if not hours worked what should he be measuring, when is it appropriate to ask people to work late, burnout, and the true measures of productivity.

Lessons Learned

Define the output you want for the company getting input from each department/division

Use Mission and Intent to create those definitions and the appropriate metrics for measuring them

Publish and communicate widely

Provide immediate feedback for course correction