Steve Blank's Blog, page 24

August 29, 2016

The National Geospatial Intelligence Agency Goes Lean

We tend to associate the government with words like bureaucracy rather than lean innovation. But smart people within government agencies are working to change the culture and embrace new ways of doing things. The National Geospatial Intelligence Agency (NGA) is a great example.

The NGA, an organization within the U.S. Department of Defense, delivers geospatial intelligence (satellite imagery video, and other sensor data) to policymakers, warfighters, intelligence professionals and first responders.

A team from their Enterprise Innovation Office has joined us at NYU as observers at our 5-day Lean LaunchPad class, while another team is in Silicon Valley with the Hacking for Defense team learning how to turn their hard problems into partnerships with commercial companies that lead to deployed solutions.

The Innovation Insurgency

Over the last year the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency (NGA) has become part of the “Innovation Insurgency” inside the U.S. Department of Defense by adopting Lean Methodology inside their agency.

In July the NGA hosted the inaugural 2016 Intelligence Community Innovation Conference with attendees from across the Department of Defense and public sector. At the conference Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Air Force Gen. Paul Selva said, “Implementing innovation [in the government and large organizations] is like a turning battleship, you may have an upset crew with cooks having to clean up spilled food and sailors falling out of beds but that ship can turn with effort. The end result is often that change can happen but it is going to come at the cost of disruption and difficulty.”

The good news for the country is that the leadership of the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency has decided to turn the ship now.

To connect to innovation centers outside the agency, their research group has set up “NGA Outpost Valley” (NOV), an innovation outpost in Silicon Valley. The NOV is building an ecosystem of innovative companies around NGA’s hard problems to rapidly deploy solutions to solve them.

To promote innovation inside the NGA, they’ve staffed an Enterprise Innovation Office (EIO) to coach, educate and advise the entire agency, from core leadership to the operational edges, with methods and concepts of validated learning through rapid experimentation and customer development.

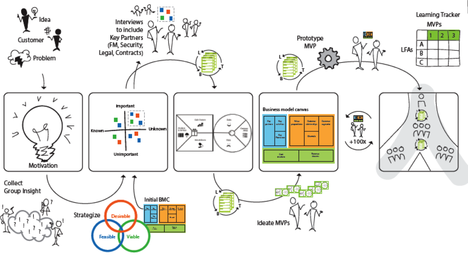

The NGA has adopted Lean Innovation methods to make this happen. The process starts by collecting agency-wide ideas and/or customer problems, collecting a group insight, and sorts which problems are important enough to pursue. The innovation process uses the Value Proposition canvas, customer development and the Mission Model Canvas to validate hypotheses and deliver minimum viable products. This process allows the agency to rapidly deliver projects at speed.

To help start this innovation program the NGA’s Enterprise Innovation Office has had their innovation teams go through the already established Innovation-Corps classes at the National Security Agency (NSA), and they’re about to stand up their own Innovation-Corps curriculum inside the NGA. (The Innovation-Corps (I-Corps for short) Program is the Lean Innovation class I developed at Stanford and teach there and at Berkeley, Columbia and NYU. It was first adopted by the National Science Foundation and is now offered at 54 universities, and starting last year taught in all research agencies and the DOD.)

This past week a team from the NGA’s Enterprise Innovation Office observed the 5-day Lean LaunchPad class I’m teaching at NYU. Their goal is to integrate these techniques into their own Lean innovation processes. From their comments and critiques of the students, they’re more then ready to teach it themselves.

At the same time the NGA Outpost Valley team was in Silicon Valley going through a Hacking for Defense workshop (we call a “sprint.”) Their goal was to translate one of their problems into a language that commercial companies in the valley could understand and solve, then to figure out how to get the product built and deployed. Like other parts of the Department of Defense (the Joint Improvised Threat Defeat Agency (JIDA) and the Defense Innovation unit Experimental (DIUX),) NGA’s Outpost Valley team is using a Hacking for Defense sprint to build a scalable process for recruiting industry and other partners to get solutions to real problems deployed at speed.

Putting lean principles into NGA’s acquisition practices

As part of the Department of Defense, the NGA acquires technology and information systems through the traditional DOD’s acquisition system – which has been described as the antitheses of rapid customer discovery and agile practices. The current acquisition system seldom validates whether a promised capability actually works until after the government is locked into a multiyear contract, and fixing those problems later often means cost overruns, late delivery, and under performance. And as any startup will tell you, the traditional government acquisition processes create disincentives for startups to participate in the DOD Market. Few startups know where and how to find opportunities to sell to the DOD, they seldom have the resources or expertise to navigate DOD bureaucratic procurement requirements, and the 12 plus months it takes the government to enter into a contract makes it cost prohibitive for startups.

A year ago Sue Gordon, the deputy director of the NGA, sent out an agency-wide memo that said in part, “…we must build speed and flexibility (agility) into our acquisition processes to respond to those evolutions. It is our job to acquire the technologies, data and services that NGA and the NSG need to execute our mission in the most effective, efficient and timely manner possible …”

A year ago Sue Gordon, the deputy director of the NGA, sent out an agency-wide memo that said in part, “…we must build speed and flexibility (agility) into our acquisition processes to respond to those evolutions. It is our job to acquire the technologies, data and services that NGA and the NSG need to execute our mission in the most effective, efficient and timely manner possible …”

In addition to NGA’s internal Lean Innovation process and innovation outpost in Silicon Valley, they are starting to use open innovation and crowdsourcing to attract commercial developers to tackle geospatial intelligence problems.

This week the NGA posted its first major open Challenge – The NGA Disparate Data Challenge– on Challenge.gov, the U.S. government’s open innovation and crowdsourcing competition. Government agencies like the NGA can use the site to post challenges and award prizes to citizens who find the best solutions. Putting a challenge on a crowdsourcing platform is a groundbreaking activity for the agency and opens the possibility for a number of benefits.

Presenting a problem instead of a set of requirements to startups leaves the window open to uncover unknown solutions and insights

Setting up the challenge in two stages hopefully gets startups to participate while learning about the NGA and its technical needs

Asking for working solutions offers the potential for minimal viable acquisition to quickly validate who can solve the problem prior to committing large sums of taxpayer funds

Finding solutions at speed by shrinking the timeline for determining the viability of a solution without the need for executing any large scale contract.

The NGA Disparate Data Challenge has two stages.

Stage 1: teams have to demonstrate access and retrieval to analyze NGA provided datasets. (This data is a proxy for the difficulties associated with accessing and using NGA’s real classified data.) Up to 15 teams who can do this can win $10,000. And the winners get to go Stage 2.

Stage 2: the teams demo their solutions and other features they’ve added against a new data set live to an NGA panel of judges, in hackathon style competition. First place will take an additional $25,000; second $15,000; and third $10,000 with an opportunity to be part of a competitive pool for a future pilot contract with NGA.

NGA’s challenge is its first attempt to attract startups that otherwise would not do business with the agency. It’s likely that the prize amounts ($10-$25K) may be off by at least one order of magnitude to get a startup to take their eye off the commercial market. Curating a crowd and persuading them to work together because the work meets their value proposition is hard work that takes incubation not just prizes. However, this is a learning opportunity and a great beginning for the Department of Defense.

Challenges in Embracing Innovation in Government Agencies

Innovation in large organizations are fraught with challenges including; building an innovation pipeline without screwing up current product development, educating senior leadership and (at times intransigent) middle management about the difference between innovation and execution, encouraging hands-on customer development, establishing links between department and functional silos that don’t talk to each other (and often competing for resources), turning innovative prototypes and minimum viable products into deliverable products to customers, etc.

Government agencies have all these challenges and more. Government agencies have more stringent policies and procedures, federally regulated oversight and compliance rules, and line-item budgets for access to funding. In secure locations, IT security can hinder the simplest process while a lack of access to a physical collaboration space and access to data, all set up additional barriers to innovation.

The NGA has embraced promising moves to bring lean methods to the way they innovate internally and acquire technology. But what we’ve seen in other agencies in the Department of Defense is that unless the innovation process is run by, coached and scaled by innovators who have been in the DOD and understand these rules (and have the clearances), using off-the-shelf commercial lean innovation techniques in government agencies is likely to create demos for senior management but few fully deployed products. (The National Security Agency has pioneered getting this process right with the I-Corps@NSA.)

Lessons Learned

Lean Innovation teams are starting up at the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency (NGA)

NGA has an Innovation Outpost in Silicon Valley working on it’s first hacking for Defense Sprint

NGA is experimenting with open innovation with its first problem on Challenge.gov

The goal of Lean in government agencies should mean deployment not demos

In order to successfully deliver products with speed and urgency, this requires coaches and instructors who have been the customer: warfighters, analysts, operators, etc.

It will take innovation built from the inside as well as acquisition from the outside to make it happen

Filed under: Customer Development, Hacking For Defense, Science and Industrial Policy

August 23, 2016

Entrepreneurs are Everywhere Show No. 40: Stan Gloss and Matt Armstead

A lot of people, especially in the Midwest, will spend their time thinking too small. They’re a creature of their habit and habitat, in looking at potential investors and market opportunities.

If you see a need or problem and you think you can solve it, you don’t want that destiny to belong to someone else.

You have to disprove the naysayers. You sometimes get a chip on your shoulder and say, “You know what? I’ll show you.

Thinking big, destiny and naysayers — three things in the life of a startup founder.

Why founders need to be their own boss and how they capitalize on business opportunities were the focus of the guests on today’s Entrepreneurs are Everywhere radio show.

The show follows the journeys of founders who share what it takes to build a startup – from restaurants to rocket scientists, to online gifts to online groceries and more. The program examines the DNA of entrepreneurs: what makes them tick, how they came up with their ideas; and explores the habits that make them successful, and the highs and lows that pushed them forward.

Stan Gloss

Joining me in the Stanford University studio were

Stan Gloss, co-founder of BioTeam, consultants that design computer systems for life sciences companies

Matt Armstead, a serial entrepreneur and co-founder of Lumos Innovation, which helps Ohio-area founders launch their startup ideas

Matt Armstead

Listen to my full interviews with Stan and Matt by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here.

(And download any of the past shows here.)

Clips from their interviews are below.

Stan Gloss co-founded BioTeam following his tenure in business development with AVAKI Corporation, a pioneer in global grid software solutions. Previously, at Blackstone Computing, a computing and IT consulting company for scientists, Gloss led the sales initiative that launched the company in the life sciences market. Prior to working at Blackstone, Gloss was a department chairman and faculty member at Quinnipiac University.

Leaving the corporate world to do a startup was a leap of faith Stan welcomed:

The previous jobs that I had in big corporations were almost like being in school again. There’s all that structure and all these things that really didn’t play to my strengths.

By being an entrepreneur I have the freedom to build things and do things that play to my strengths.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

—

Stan was an account manager at Blackstone Computing when the company was reorganized under a new CEO. Though they’d never done a startup before, Stan and some of his co-workers saw an opportunity in the leadership change. Together, they started down a new path:

Eventually we saw the writing on the wall with the new company and four of us decided to go off on our own and continue doing the consulting piece of what we did.

We were already entrepreneurial. We just took a leap of faith and said, “We can get all the clients that we had in the consulting company, and we can go out and get more of them together. Look at how good we did here. Let’s just go do that.”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Starting the company was a little scary, but it helped that Stan was surrounded by domain experts and recognized his personal strengths, he says:

Everything was new every day. I didn’t even know that area, so I used to sit at meetings and not understand the science. I really didn’t understand high-performance computing either.

But I knew how to make meetings productive, I knew how to facilitate meetings, and I was smart enough to put our domain expert in the room with the domain expert from the customer.

I used to sit there and just let them talk — and then collect the order at the end.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Stan adds that being dyslexic gives him an edge as a founder because from an early age he had to develop skills that turn out to be critical when building a startup:

Every day in school was a day of fear, uncertainty and doubt. You never knew if you were going to get called to the board, you were going to have to stand up and read, all of these things that are very challenging for kids like me with dyslexia. School became was just day-in and day-out hard to do.

You learn to become comfortable with being uncomfortable. You learn to outwork everybody.

You also learn to negotiate. You say, “Hey listen, you’re good at math. I’m good at English. I’ll do your homework if you do mine.” Or you negotiate with the teacher.

And you face people telling you, “No, you’re not going to go to college, no you’re not going to be doing this, no you’re not going to be doing that.” You have to disprove the naysayers. You sometimes get a little chip on your shoulder and say, “You know what? I’ll show you.”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

—

Having now done several startups, Matt has learned to keep his eye on a singular aim: The goal is to get customers, not to raise money:

There are a lot of people that are just chasing dollars, trying to get a VC to fund them, and they’ll give up 40 percent of their company in the first round just to get some major amount of money.

I learned that you can actually do things very inexpensively. You can bootstrap it. You can build a Minimum Viable Product. You can learn from your customers.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

He learned, too, that building a company outside a major startup ecosystem like Silicon Valley doesn’t have to limit a founder’s horizons:

A lot of people, especially in the Midwest, will spend their time thinking too small. They’re a creature of their habit and habitat, in looking at potential investors and market opportunities.

They have to think outside of their own back yard, get really active and make trips out to San Francisco or to New York to build some very important relationships.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Matt’s advice for other entrepreneurs included this recommendation about finding co-founders:

I’ve talked to a lot of startup and entrepreneurs that need to find a technical co-founder. They’re just looking for the first person that can code, the first person that fits that capability that they’re looking for.

That’s a mistake. You really have to date a little bit. You have to build a relationship with a prospective co-founder. These are the people you’re working 24/7 with.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Listen to my full interviews with Stan and Matt by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here. (And download any of the past shows here.)

Next on Entrepreneurs are Everywhere: Chris Schroeder, Internet/media CEO, venture investor and author of “Startup Rising: The Entrepreneurial Revolution Remaking the Middle East” and Andy Cunningham, founder and CEO of Cunningham Collective.

Tune in Thursday at 1 pm PT, 4 pm ET on Sirius XM Channel 111.

Want to be a guest on the show? Entrepreneurship stretches from Main Street to Silicon Valley, from startups to big companies. Send an email to terri@kandsranch.com describing your entrepreneurial journey.

Filed under: Customer Development, SiriusXM Radio Show

August 19, 2016

Clusters, Class, Culture and Unfair Advantages

I just finished reading J.D. Vance’s excellent book Hillbilly Elegy, and had that funny feeling when you find the story arc of someone else’s life eerily paralleling yours.

Vance’s book and the story of my own life suggest that there is an archetypal journey (a pattern of human nature) that describes the flight from a dysfunctional family and the escape from the constraints of cluster, class and culture.

Here’s how my story unfolded.

Limited Horizons

I grew up in New York in a single-parent household that teetered on the bottom end of lower middle-class in what today we’d call “working class.”

In my neighborhood, successful entrepreneurship meant small businesses entrepreneurs. Before my parents divorced they had owned a small grocery store. One neighbor owned the corner drug store, and another had a furniture store, though most of our neighbors were simply employees with 9-5 jobs in retail and construction. No one I knew had a white-collar job let alone were executives. (Eating out meant a slice of pizza or as a treat, a deli. I wouldn’t eat in a real restaurant until I went to college. I would then discover that this thing called “salad” was ordered before the main course.)

No one I knew had ever started a company (other than a small business). None of the relatives of my parents’ generation had gone to college. The highest aspirations immigrant parents had for their children in my social class were: doctor, lawyer or an accountant – and to drive a Cadillac and live in a house in the suburbs.

Graduating high school our collective aspirations weren’t much higher. Our overworked guidance counselors were adept at slotting most kids on the bottom of the deck into potential blue-collar jobs. In my graduating class of 1,000 students, the “smart kids” wanted to be teachers. A few even aspired to be writers, poets or scientists. The guidance counselors steered them into good state schools.

I was pretty much on my own in high school, which was a huge improvement over the previous 5 years. (Having interludes of normalcy by visiting my aunt’s house a few miles away was one of my havens of sanity and stability. Watching her family having dinner together or listening to them describe their weekend outings or vacations, I remember thinking how weird their family was. It would take me a long time to realize that this is what normal families do together.) My mother was rarely home and never asked about or looked at my homework. I signed (forged) all my report cards. My final grades in my senior year classes were four “mercy” 65’s (the minimum passing grade) and one 98. Most of my classmates who opted for college went to the local colleges or New York State University schools. (The Vietnam War was raging, but going to college gave you a draft deferment.)

Interestingly, none of us believed our possibilities were limited, yet in hindsight our first barrier was that knowledge was local – constrained by our culture and cluster. (Forty years later when the Internet has made knowledge global, we’ve run into the second barrier – just knowing about things is not the great equalizer we expected. We’ve rediscovered that career choices are referential and experiential. Just because you read about it does not mean you know how to apply it to your own life. We still tend to gravitate to careers we’re exposed to in local clusters, and bound by our class and culture.)

In short, even though it was 15 miles into midtown Manhattan, our horizons were limited, and mine, perhaps even more limited. (I would visit my first museum in Manhattan only years later when I returned to New York with my girlfriend showing me around as a tourist.)

The notion of having an idea and building a company was unimaginable. We weren’t dumber than the kids who eventually would populate Silicon Valley, but our career trajectories had been flattened by the limited knowledge and expectations of our cluster, class and culture.

(A cluster is a concentration of interconnected businesses in a specific field in one city or region. Silicon Valley is an innovation cluster that makes hardware, software, biotech and semiconductors. Detroit is an automotive cluster, Hollywood an entertainment cluster, New York City for media and financial services, etc. Class is short for “social class” and refers to wealth, but also to education and social status. Culture is the shared beliefs of others around you. Culture has a strong correlation with class but also is influenced by ethnicity, religion, region, etc.)

Fly Away

Unlike my peers with stable families who stayed in New York, my untenable home life provided the escape velocity for me to leave New York. I wanted to get as far away from it as I could. However, filling out a college application was a mystery to me — What were the right colleges to apply to and how should I answer the questions on the application? Somehow I figured out how to apply to school in Michigan. (Pre-infinite information on the Internet about colleges, I picked Michigan because I saw them play football on TV, but I ended up applying to the wrong school in Michigan – my first time around I ended up in Michigan State not the University of Michigan. Lucky for me as I never would have been accepted. After the Air Force I found the right Michigan.)

But once I made it to college I was lost. I had none of the discipline, study skills and preparation I needed. After one semester, I dropped out when my girlfriend said, “Some of us actually want to be here and are working hard to learn something,” and I realized she was right. I had no idea why I was in school. Some small voice in the back of my head said that to survive I needed some sort of structure in my life, and had to learn some marketable skills.

In the middle of a Michigan winter, I stuck out my thumb and hitchhiked to Miami, the warmest place I could think of. I had no idea what would be at the end of the highway. But that day I began a pattern that I still follow—stick out your thumb and see where the road takes you.

I managed to find a job at the Miami International Airport loading racehorses onto cargo planes. I didn’t like the horses, but the airplanes caught my interest. A technician took me under his wing and gave me my first tutorial on electronics, radar and navigation. I was hooked. For the first time in my life, I found something I was passionate about. And the irony is that if I hadn’t dropped out, I would never have found this passion…the one that began my career. If I hadn’t discovered something I truly loved to do, I might be driving a cab at the Miami airport.

While college had been someone else’s dream, learning electronics became mine.

So I enlisted in the Air Force during the Vietnam War to learn how to repair electronics. I didn’t tell my family I had enlisted (I told them I was going camping) figuring that if I couldn’t make it through basic training, no one would know. (It turns out my unconscious search for a stable, structured environment is a common theme among many military recruits.)

After nine months in electronics school, when most everyone else was being sent overseas to a war zone, I was assigned to one of the cushiest bases in the Air Force, right outside of Miami.

My first week on the base our shop chief announced: “We’re looking for some volunteers to go to Thailand.” I still remember the laughter and comments from my fellow airmen: “You got to be kidding, leave Miami for a war in Southeast Asia?” Others wisely remembered the first rule in the military: never volunteer for anything. Listening to them, I realized they were right. Not volunteering was the sane path of safety, certainty and comfort. So I stepped forward, raised my hand—and I said, “I’ll go.”

I was going to see where the road would take me. Volunteering for the unknown, which meant leaving the security of what I knew would continually change my life. People talk about getting lucky breaks in their careers. I’m living proof that the “lucky breaks” theory is simply wrong. You get to make your own luck. 80% of success in your career will come from just showing up. The world is run by those who show up…not those who wait to be asked.

For four years I worked within a “cluster” of like-minded individuals (the Air Force) who shared the same mission. More importantly, as an electronics technician, I was now hanging out with a crowd of pretty smart guys (the military was then all guys) repairing complex electronics and microwave systems.

We tutored each other, read books together, went on adventures together and learned together. And while most of us came from totally different backgrounds (I never knew you put salt of watermelon, that Spam was food or muffuletta was a sandwich), as far as the military was concerned, we were all the same “class” – enlisted men – denoted by the rank on our sleeves. And what I didn’t realize at the time is that I was being mentored some of the senior enlisted guys a decade or two older than me. I’m not sure it was a conscious effort on their part, (I know it wasn’t on mine) but what people don’t realize is that mentorship is a two-way street. While I was learning from them – and their years of experience and expertise – what I was giving back to them was equally important. I was bringing fresh insights to their data. This pattern of mentorship would continue and profoundly impact my career in Silicon Valley.

So here I was 19, my first days of adulthood, in the middle of a confusing and unpredictable war zone learning how to repair electronics as fast as I could. It was everything life could throw at you at one time with minimum direction and almost no rules. (Service in the military is a life and death lottery. While we were living the good life in Thailand, the Army and Marines were pounding the jungle every day in Vietnam. Some of them saw death up close. 58,000 didn’t come back – their average age was 22.)

A few years of this sifted and sorted us in a way that foreshadowed our future career paths. It turned out that the skills I had learned growing up in order to survive in constant disorder turned out to be what I needed to excel in this environment: comfort in working in chaos and uncertainty (heck, that was how I woke up every day), pattern recognition (if you couldn’t see it coming before others, you were screwed) and the ability to shut down external distractions and relentlessly focus on a single problem (staying sane in my home life.) While I might have refined these skills in a different environment, the sink-or-swim daily exigencies of the Vietnam War honed them to a fine point.

These would be the identical skills I would need to succeed in Silicon Valley. Though I would pay the cost of having learned them for the rest of my life.

While the paths of our lives would radically diverge, for the first time I had a sense of a cluster, class and culture where it felt like I belonged. The Air Force turned out to be the first melting pot I would encounter (Silicon Valley the next) where individuals from different classes and culture had the opportunity to share a common goal and move beyond the environment they grew up in (foreshadowing Silicon Valley startup culture.)

When I came back from Southeast Asia, I was assigned to a Strategic Air Command base with nuclear armed B-52s in Michigan where the Calvin Ball rules of a war zone — “do what you need to do to get the job done” — no longer applied. It was now, “follow the rules exactly” – not something I was really good at. Realizing that this wasn’t the long-term profession for me, I left after my four years were up, having learned electronics and gained awareness of a larger world and career paths.

Silicon Valley

I now found myself back in school in Michigan, and my girlfriend who first told me to leave as an undergraduate was now my wife working on her Ph.D. Within a year I would drop out again (a divorce, and an extreme lack of interest in theory and more desire for practice – more payback for learning survival versus social skills). It would be the last time I would spend on a college campus as a student. It would take 25 years to return to a campus — this time teaching at Berkeley, Stanford, NYU and Columbia.

I found a job in Ann Arbor working as a field engineer. Decades later, I realized that the broadband network company where I worked, installing high-speed process control networks in automobile assembly plants and steel mills (before Ethernet existed), was one of the few pioneering startups in Ann Arbor. It would turn out to be the first of many bridges to somewhere else.

One day the company sent me and an engineer across the country, to a city none of us had ever heard of – San Jose, California – to install a process control system in a Ford Assembly plant. (We were so clueless about where San Jose was that at first the company admin got me tickets to San Jose Puerto Rico.)

Getting off the plane and into our rental car headed to our motel we tuned the radio to the local music station and a commercial came on blaring, “scientists, engineers, technicians, Intel is hiring…” We almost drove off the road. Did we just hear this right? Someone is advertising electronics jobs on the radio? And then the music came back on like this was just another ad. WTF?

To put our reaction in context, in Ann Arbor there really wasn’t much of an electronics cluster (a few machine vision companies), so for amusement each week a few of us would scour the local newspaper for electronics job listings to see if other companies were paying any better than ours. It was a good week when we would find one or two listings. What kind of place were we in that advertised for engineers on the radio?

After we checked into our motel, I bought the Sunday edition of the local newspaper – the San Jose Mercury News. I was a bit confused why this newspaper was thicker than the Sunday New York Times. In our room, as my roommate grabbed the shower first, I turned on the TV and started flipping through the paper. First section – normal news, second section – normal sports, third section – normal arts/entertainment, fourth section – classified ads and more classified ads and more classified ads and more classified ads. In fact, there were 48 pages of classified ads (I counted them several times) and almost all of them were for scientists, engineers, technicians, and tech support – woah.

Just as I was trying to process what I was seeing in the newspaper, thinking this couldn’t be real, the TV program switched to an ad and snapped my head right out of the newspaper with an earsplitting – “Engineers, looking for a better job? Four-Phase Systems is hiring…”

I leapt off the bed, banged on the bathroom door, dragged my roommate out of the shower, and with a towel wrapped around him we both stared at the TV and caught the last few seconds of the TV commercial. There would be several more during our stay. We spent that evening reading every one of the 48 pages of job listings.

The next day, working at the Ford assembly plant, I kept wondering, “Where the hell was I? How come none us had ever heard of this place?” (The answer was that Silicon Valley at the time was primarily building military weapons systems, semiconductors and test equipment, all business-to-business sales with no products aimed at consumers.)

After our work in San Jose was done, the engineer who came out with me flew back home. (For decades I couldn’t understand why. All he said was, “My parents are in Michigan.”) With nothing holding me to any place, I stayed, started interviewing and got my first job in the Valley.

My horizons of cluster, class and culture were about to expand once again. I felt like I was in on a secret no one else had yet understood. In phone calls to my friends back in Ann Arbor I tried to explain what was happening here, but to be fair even I didn’t understand we were standing at ground zero of inventing the future. Here was an environment where what you could accomplish meant more than who you knew. Technologists were running companies, as no serious MBAs would go near these places, and investors were company builders, teaching founders how to grow revenue and profit. While I would struggle for years accepting help from others (in my previous life it always came with strings) those who succeeded paid it forward by sharing what they had learned with new arrivals like me.

Endlessly curious, I drank from the firehose of opportunity that was the valley. I went from startups in military intelligence to microprocessors to supercomputers to video games to enterprise software. I was always learning. There were times I worried that my boss might find out how much I loved my job…and if he did, he might make me pay to work there. To be honest, I would have gladly done so. While I earned a good salary, I got up and went to work every day not because of the pay, but because I loved what I did.

As an entrepreneur in my 20s and 30s, I was lucky to have four extraordinary mentors, each brilliant in his own field and each a decade or two older than me. For the next four decades I would work for them, be mentored by them, co-found companies with them and get funded by them.

In Silicon Valley in the 1970s, I had come pretty far from someone who had puzzled through how to fill out a college application. Though the imprints of how I grew up would always be with me, (many detrimental) through intuition, curiosity and luck, I had started to move beyond the cluster, class and culture of my youth.

——

In reading Hillbilly Elegy I realized that my story is not just my story, it’s a recurring archetypal journey about lucky individuals — those whose brain chemistry is wired for resilience and tenacity and who manage to flee from a dysfunctional family and escape from the constraints of cluster, class and culture. They come out of this with a compulsive, relentless and tenacious drive to succeed. And they channel all this into whatever activity they can find outside of their home – sports, business, or …entrepreneurship.

Lessons Learned

Your local environment – cluster, class and culture – shape your initial trajectory

Some people who don’t have the advantages of cluster, class and culture growing up will seek them out

It takes a lot of escape velocity to break out

Filed under: Air Force, Family/Career/Culture

August 15, 2016

Entrepreneurs are Everywhere Show No. 39: Jeremy Johnson and Michael Eidsaune

The existence of a problem doesn’t mean there’s a solution to that problem. Wanting to create impact is great. But to do it, you need to actually have a sustainable business model.

I don’t recommend anyone become an entrepreneur. It’s too hard. It’s too painful. Starting a business is too risky. There are better ways to make a living. Yet I can’t imagine doing anything else.

One mistake was trying to build out too much tech too quickly. We thought that the tech was going to be the solution, that if we added more features, it would solve the problem. We were wrong.

Identifying a problem doesn’t mean you’ve automatically created a business.

And building a startup is not for the faint of heart.

The tools and temperament needed to get from startup idea to startup success were the focus of the guests on today’s Entrepreneurs are Everywhere radio show.

The show follows the journeys of founders who share what it takes to build a startup – from restaurants to rocket scientists, to online gifts to online groceries and more. The program examines the DNA of entrepreneurs: what makes them tick, how they came up with their ideas; and explores the habits that make them successful, and the highs and lows that pushed them forward.

Jeremy Johnson

Joining me in the Stanford University studio were

Jeremy Johnson, founder of Andela, which embeds talented software engineers on the African continent into top engineering organizations worldwide

Michael Eidsaune, co-founder of Carely, a software platform that facilitates communication among families caring for sick or elderly relatives

Michael Eidsaune

Listen to my full interviews with Jeremy and Michael by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here.

(And download any of the past shows here.)

Clips from their interviews are below.

Jeremy Johnson is an education innovator. Prior to founding Andela, he co-founded 2U, an education technology startup that went public in 2014.

Outside of Andela, Jeremy serves on the board of the Young Entrepreneur Council and the education non-profit PENCIL and co-authored a book Education & Skills 2.0: New Targets & Innovative Approaches.

Before founding 2U, Jeremy developed Zinch, intended to be a virtual guidance counselor to help low-income students navigate the college application process. He explains why it didn’t get off the ground:

It was a great idea, but a terrible company.

It turns out the existence of a problem doesn’t mean there’s a scalable or profitable way to solve that problem — or at least at the time.

The goal was to help low-income students better understand the college application process.

For the past 30 years great colleges have approached recruitment by creating a list of names from the PSATs and then sending out glossy brochures. Often they don’t think about it through the lens of what is the best way to spend or allocate resources to try to get better students. So while Zinch was trying to create an offering that would support low-income students that wasn’t where the majority of college recruitment dollars were being spent. So it was tough. We couldn’t charge the low-income students we were looking to help enough to keep the business going.

In the end we learned that wanting to create impact is great. But to be able to do it, you need to actually have a model that sustains it.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here.

The effort was a good learning experience, he says:

The beauty of trying things when you’re 21 and have no idea what you’re doing is that you get the chance to make a lot of mistakes really quickly and learn from them.

One mistake we made was trying to build out too much tech too quickly and thinking that the tech was going to be the solution, that if we added more features, it would solve the problem. We were wrong.

We thought, ‘Why don’t we think through all of the different potential users that might use a system and how they might want to interact with it?’

We tried to boil the ocean in the most literal sense.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Prior to founding Carely, Michael Eidsaune earned his MBA in finance and spent several years in investment management, eventually earning his level 1 CFA certification. He also worked for a time as a contract negotiator for the US Air Force.

The idea for Carely was sparked by personal family experience. Michael started the company with his father-in-law, working on it part-time, while he worked with the Air Force.

Since its founding four years ago, Carely has seen ups and downs. Michael’s vision and passion have gotten him through it:

I don’t recommend anyone do this. It’s too hard. It’s too painful. Starting a business is too risky. There are better ways to make a living that are much safer.

And yet, while I would never recommend anybody do this, I can’t imagine doing anything else.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

—

An experienced team made all the difference to 2U finding success, Jeremy said:

We had a phenomenal early group of people that were brought together to try to address the problem.

You might look at it and say, “In some ways, that team is overkill for an early-stage company. These people are overqualified for what they’re doing.”

But it turns out that when you’re growing really quickly, having folks who have been through it a couple times before is really useful in the early days, even to make sure that you’re able to really grow effectively while maintaining culture.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Andela selects and trains world-class tech talent from Africa and matches them with U.S. companies. Here’s how Jeremy came up with the idea for Andela, and why he decided to create the company even though he was still working on 2U at the time:

A good friend invited me to Nairobi to give a talk for the MasterCard foundation on the state of online education around the world. That kicked off this long conversation about how you might try to leverage this evolution of education technology to create scalable impact in places where tuition couldn’t be the driver of growth.

At the same time, I’d gotten to know a young Nigerian serial entrepreneur who had become sort of a friend and mentee, and was building something similar to 2U but focused on Africa. Through those two experiences I became more and more familiar with the continent. As I was thinking through the notion of what would become Andela, my initial thinking was, “We’ve just gone public. We’ve got a lot of work to do. This is not something I can spend time on. I could potentially fund it and put the team together, but I’m busy.”

At the same time I thought, “This should exist in the world.” We put a small team together, funded it initially, put a pilot together. We were looking for four students for the program, four developers in training, and we ended up getting 700 applicants in a week.

We got that down to six finalists. I went to Nigeria to meet that first cohort, interview them and try to pick four from the six. I realized after half a day of interviews that each one of them would’ve run circles around my classmates at Princeton.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Jeremy dropped out of Princeton to become an entrepreneur. Here’s what he says about founders going to college:

You’re never going to convince someone to work with you because you have a degree.

You’re never going to come up with a different strategy for how you approach the world. You’re never going to raise funding or bring in different teams by virtue of your degree.

A college degree is great if you’re looking to get hired. But if your goal is to be an entrepreneur then it’s a little bit different and folks care a little less about it.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

—

Carely was built to foster communication among family members with sick or elderly relatives in a nursing home, assisted living residence or hospice care.

At first Michael and his co-founder thought they’d be selling to individual users, but after talking with service providers, they realized there was a bigger opportunity:

I took our prototype – a PowerPoint presentation — out and sat down with several CEOs of a hospice organization, a nursing home, home-care company and said, “Hey, this is something we think we would use as a family. Tell me why it won’t work.”

In doing that, we learned that the problem was more applicable than just our family — that lots of people were dealing with this idea of miscommunication and frustration wrapped around care giving.

We realized that there was a value proposition there for the actual industry. The providers of care actually liked the product and would pay for it because when a family’s not doing a good job communicating with each other around their loved one, it’s often the facility or the care provider that has to step in and play middleman to those conversations.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

A pivotal meeting with nurses at Hospice of Dayton in Ohio helped them figure out what features to build:

It was a bit like leading sheep to wolves, and became one of our biggest learning moments.

The reality is nurses don’t have a lot of extra free time to learn a new system and to try something new. They wanted something that would help improve the lives of their clients’ families. They loved that part of the company. But they didn’t want to have to learn a new system and learn a new task and add something to their to-do list at the end of the day.

So we just said, “OK, if you guys don’t want that piece of it, we’ll leave it out.”

At this time, we hadn’t even built the product yet. We hadn’t invested any money into development, so we just didn’t develop that piece.

If we’d built the product first, however, we would have wasted months and thousands of dollars.

This is a perfect example of why it’s important to talk to customers. For the first six months we spent only a couple of hundred bucks.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Somewhere along the line, however, Michael and his co-founder stopped listening to customers. Here’s what happened:

We got the product out; we got paying customers.

We thought we figured it out. We assumed we had product-market fit and all we had to do was keep selling.

The problem was had the wrong business model at the time. Our revenue model was wrong.

We were charging a really high up-front annual fee to these providers and the end result of that was a pretty long sales cycle. It involved lots of face-to-face selling and it wasn’t enabling us to scale the product very quickly.

It took about 2 months to realize we needed a new pricing strategy, from, an average $5,000 to $10,000 a year per provider to about a $99 a month provider fee.

We tested the new strategy with several customers in the pipeline and it took our sales cycle from about 60 days to 1 week. Plus, it enabled us to scale much more quickly with much less effort.

But by then we were so far along our original path. My co-founder didn’t quite agree with the change of direction because it was going to involve us taking on some outside capitol.

I made the tough decision to go against what he wanted to do and it led to us kind of breaking up the company at the time.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Listen to my full interviews with Jeremy and Michael by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here (And download any of the past shows here.)

Next on Entrepreneurs are Everywhere : Stan Gloss, co-founder of BioTeam; and Matt Armstead, co-founder of Lumos Innovation.

Tune in Thursday at 1 pm PT, 4 pm ET on Sirius XM Channel 111.

Want to be a guest on the show? Entrepreneurship stretches from Main Street to Silicon Valley, from startups to big companies. Send an email to terri@kandsranch.com describing your entrepreneurial journey.

Filed under: Customer Development, SiriusXM Radio Show

August 10, 2016

Hacking for Defense in 2 minutes

Hacking for Defense in 2 minutes.

If you can’t see the video click here

Hacking for Defense class here

Hacking for Diplomacy class here

Filed under: Hacking For Defense, Teaching

August 8, 2016

Entrepreneurs are Everywhere Show No. 38: Ryan Smith and Lane Merrifield

If you don’t value your product neither will your customers. No one used it when we gave it away for free. Freemium was a going out of business strategy.

When a reporter asked, “Your kids must think you’re the coolest dad in the world,” I couldn’t answer the question, because I realized that I hadn’t seen my kids in three weeks.

I learned that making a complicated thing look easy is extremely hard.

—

People appreciate things more when they pay for them. And no amount of business success is enough if you don’t have time with your family.

Values – who and what founders and customers hold dear – were the focus on today’s Entrepreneurs are Everywhere radio show.

The show follows the journeys of founders who share what it takes to build a startup – from restaurants to rocket scientists, to online gifts to online groceries and more. The program examines the DNA of entrepreneurs: what makes them tick, how they came up with their ideas; and explores the habits that make them successful, and the highs and lows that pushed them forward.

Ryan Smith

Joining me in the Stanford University studio were

Ryan Smith, co-founder of Qualtrics insight platform

, founder of Fresh Grade learning collaboration solution

Lane Merrifield

Listen to my full interviews with Ryan and Lane by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here.

(And download any of the past shows here.)

Clips from their interviews are below.

Ryan Smith co-founded Qualtrics in 2002 with his father in the family basement. Their goal was to make sophisticated research simple. As CEO, Ryan has grown Qualtrics to one of the fastest-growing technology companies in the world.

In the early days of building Qualtrics, Ryan tried giving the product away to entice customers to use it. Their reactions surprised him:

There’s something about people appreciating something they have to pay for.

Our pricing model was something like $5,000 a school. For the big schools we tried to give it away, but in every school we gave it away to, no one ever used it.

I remember that at Wharton I gave it to them free, went back a year later and there were only, like, five people using it. We had to charge them to get them to use it. Now there’s thousands of users across campus.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Lane Merrifield is a co-founder and CEO of FreshGrade, a learning collaboration and portfolio tool focused on enhancing teachers’ lives and making students’ learning visible. Lane’s first startup was Club Penguin, the largest online virtual world for kids, which was acquired by The Walt Disney Company in 2007 for $350M. Lane served as Executive Vice President at Disney for five years before returning to his entrepreneurial roots to become an angel investor and launch FreshGrade.

Lane also founded Wheelhouse, a Canadian organization that supports other entrepreneurs through mentorship, access to early stage capital, and connections to global business networks and executive expertise.

Lane explained that and his co-founders, Lance Priebe and Dave Krysko, built Club Penguin to give their kids a safe place to play online. It quickly became a hit, but that success had a dark side, Lane says:

It totally consumed my life.

I was sitting in a press interview in Australia talking about Club Penguin, and the reporter asked, “Your kids must think you’re the coolest dad in the world.” I gave her some pat answer –“Well, they like to play it once in a while, but to them I’m just dad” — but I almost couldn’t answer the question, because I realized in that moment that I hadn’t seen my kids in about three weeks.

Ironically, this thing that I built for them now had me traveling around the world and being a pretty crappy dad.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

—

Finding early customers for Qualtrics was difficult, Ryan says. It was a challenge to convince companies to think past the traditional method of hiring consultants or researchers to test user experience:

At first I tried to call business and enterprises. But in the corporate world in 2002, no one was ready for it.

I specifically remember calling one airline, and they said, “Hey look, if our customers aren’t happy, they’ll just call us.” Now today that mindset seems silly.

In the meantime, we had this case study that said academics were really ready for us. So we started in the academic market — because they would actually buy. I remember selling Angela Lee at the Kellogg School of Business, and Angela referred it to someone at Wharton, who referred it to someone at Columbia and Duke, and the rest is history.

Ironically, though, academics are horrible customers. They have a laundry list of features they want that are more than you can listen to in an hour. They’re hard to service and support because they want to talk to someone as smart as them, which is almost impossible, and they have no money. No MBA business model would ever come out with, “Hey we’re going to go target the academics.”

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Still, academics made up Qualtrics’ core market for five years. Over time, students at those institutions took the product with them into their corporate jobs, growing Qualtrics’ customer base.

While it looked to the world like Ryan and his team planned to grow that way, nothing could be further from the truth.

Everyone comes up now — the VCs, the market – and they say, “Hey wow, that was a beautiful business model. You guys were geniuses.”

I kind of start laughing because no one ever thought we were geniuses; it was desperation. Typically that’s when innovation comes out. You innovate when you’re desperate.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

One important lesson Ryan learned was how difficult it is to make a complicated thing seem seamless:

Everything my dad wanted to build was way too complex for anyone to understand. So we had this built-in test where we’d see if I could figure it out, because if I could figure it out, then others could.

I learned that making a complicated thing look easy is extremely hard.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

—

Club Penguin launched with modest expectations. Lane and his team built a virtual world to give their kids a safe place to socialize online, thinking others might like it, too. They were in for a big surprise:

Our hope was just to be able to find enough people out there that we could keep it sustainable. We bootstrapped it. We took out lines of credit on our homes; we maxed out credit cards. There were no investors.

We hired a few people part-time, we contracted a lot of work, we’d pay as often as we could, and we started a subscription business, which back in the day was insanity. It was freemium, but the term freemium didn’t exist yet. It was try and then buy.

Through some of these mini-games that my co-founder, Lance, had created, we had a small audience initially. But when we rolled out the virtual world, it grew from a few thousand kids to 30,000 or 40,000 within about a month.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Built before Facebook existed, the company was at the cutting edge for scale, which attracted potential investors, but also presented some interesting challenges:

We had some great VCs come out of the woodwork, and we said, “Listen, have you dealt with infrastructure problems like this before? We have hundreds of thousands of concurrent users logging into servers that are meant to be having long, 2-, 3-, 4-minute sessions, and we’re having millisecond sessions, and our servers can’t handle that?”

We brought in experts from IBM, we worked with the biggest service providers in the world, and some of the largest data centers. They all had no idea what to do with us, because they were used to a database and the web, and the web sessions last for minutes at a time. At this point in time, we had hundreds of thousands of users. We were basically hacking these servers to do what we needed them to do.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Like most founders, Lane and Ryan are glad to pay their success forward.

Today, in addition to running FreshGrade, Lane mentors other founders. He tells them this:

Know why you’re doing what you’re doing. Don’t focus on the what, don’t tell me about the market opportunity, don’t tell me, “I’m Uber for this” or “I’m Slack for that.”

I don’t care about that. Tell me why are you building what you’re building.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

He said that because the Club Penguin team was clear about their “why,” they embraced being acquired by Disney in 2007:

Our goals weren’t about an exit. I didn’t even know what the term “exit” meant. For us, it was about taking Club Penguin to the next level.

By the time we were acquired we had millions of users, we had a massive demand for consumer products, massive demand internationally. We needed to translate the game into other languages. We didn’t have any of the infrastructure to do that.

Disney gave us more resources to make our vision happen.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Ryan counsels other founders to never give up. Qualtrics has 8500 customers today, but back in his father’s basement in 2002, things weren’t so rosy. This memory helped him keep things in perspective along the way:

I remember thinking, “We’re in the basement, no one knows about us. We need to go to a trade show and get some exposure.” I called this trade show company that was putting on this great marketing event in New York City.

I borrowed my brother’s trade show booth and flew to New York. We took the train from the airport, because we couldn’t afford a taxi, and I sat on the train with this trade show booth in a bag between my legs. I remember specifically hauling that thing up the stairway and coming out of the subway station pretty close to Wall Street.

Fast-forward ten years. We were hosting a Qualtrics Live event for our customers in New York City in a hotel in the same neighborhood where the trade show had been. We now had 250 New York customers there; the room was full. Coming out of the hotel walking around the street, I was looking for somewhere to eat, and I passed that subway station. I could almost picture myself as a young kid hauling that trade show booth up the stairs.

It was kind of surreal, a message like, “Don’t give up. Trust your ideas.”

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve had to rely on that memory and the lessons I learned from hauling that trade show booth up the stairs.

If you can’t hear the clip, click here

Listen to my full interviews with Ryan and Lane by downloading them from SoundCloud here and here. (And download any of the past shows here.)

Next on Entrepreneurs are Everywhere : Jeremy Johnson, founder of Andela; and Michael Eidsaune, co-founder of Carely.

Tune in Thursday at 1 pm PT, 4 pm ET on Sirius XM Channel 111.

Want to be a guest on the show? Entrepreneurship stretches from Main Street to Silicon Valley, from startups to big companies. Send an email to terri@kandsranch.com describing your entrepreneurial journey.

Filed under: Customer Development, SiriusXM Radio Show

August 4, 2016

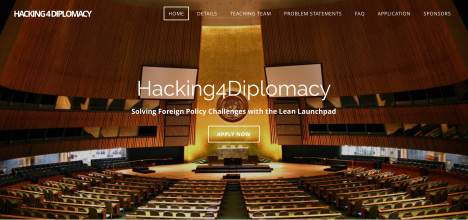

Hacking for Diplomacy – Solving Foreign Policy Challenges with the Lean LaunchPad

Hacking for Diplomacy is a new course from the Management Science and Engineering department in Stanford’s Engineering school and Stanford’s International Policy Studies program that will be first offered in the Fall of 2016.

Join a select cross-disciplinary class that takes real problems from the U.S. State Department and asks students to use Lean Methods to test their understanding of the problem and deliver rapid-fire innovative solutions to pressing diplomacy, development and foreign policy challenges.

Syrian Refugees, Human Trafficking, Zika Virus, Illegal Fishing, Weapons of Mass Destruction Detection, ISIS on-line propaganda, Anti-Corruption…

What do all these problems have in common? The U.S. Department of State is working on all of them.

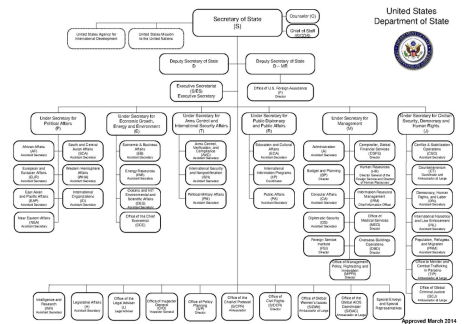

The U.S. Department of State manages America’s relationships with 180 foreign governments, international organizations, and the people of other countries with 270 embassies, consulates, and other posts. The management of all these relationships is called diplomacy. 70,000 State Department employees (46,000 Foreign Service Nationals, 14,000 Foreign Service Employees and 11,000 in the Civil Service) carry out the President’s foreign policy and help build a freer, more prosperous, and secure world.

The State Department has four main foreign policy goals:

Protect the United States and Americans

Advance democracy, human rights, and other global interests

Promote international understanding of American values and policies

Support U.S. diplomats, government officials, and all other personnel at home and abroad.

At a time of significant global uncertainty, diplomats are grappling with a set of transnational and cross-cutting challenges that defy easy solution. These include the continued pursuit of weapons of mass destruction by states and non-state groups, the outbreak of internal conflict across the Middle East and in parts of Africa, the most significant flow of refugees since World War II, and a changing climate that is beginning to affect both developed and developing countries. And that’s just on Monday. The rest of the week is equally busy.

Hacking for Diplomacy

In a world of complex threats, dynamic opportunities, and diffuse power, effective diplomacy and development require institutions that adapt, embrace technology, and allow for experimentation to ensure continuous learning. This means developing new and innovative ways to think about, organize and build diplomatic strategies and solutions. Stanford’s new Hacking for Diplomacy class is a part of this effort.

Hacking for Diplomacy is designed to provide students the opportunity to learn how to work with the Department of State to address urgent foreign policy challenges. While the traditional tools of statecraft remain relevant, policymakers are looking to harness the power of new technologies to rethink how the U.S. government approaches and responds to the problems outlined above and other long-standing challenges. In this class, student teams will take actual foreign policy challenges and a hands-on approach that will require close engagement with officials in the U.S. State Department and other civilian agencies. They’ll learn how to apply “lean startup” principles, (“mission model canvas,” “customer development,” and “agile engineering”) to discover and validate agency and user needs and to continually build iterative prototypes to test whether they understood the problem and solution.

Each week, teams will use the Mission Model Canvas (a variant of the Business Model Canvas used for government agencies and non-profits) to develop a set of initial hypotheses about a solution to the problem and will get out of the building and talk to relevant stakeholders and users. As they learn, they’ll iterate and pivot on these hypotheses through customer discovery and build minimal viable prototypes (MVPs). Each team will be guided by a sponsor from the State Department bureau that proposed the problem and a second mentor from the local community.

Real Problems

In this class, student teams select from an existing set of problems provided by the Department of State. Hacking for Diplomacy is not a product incubator for a specific technology solution. Instead, as teams follow the Mission Model Canvas, they’ll discover a deeper understanding of the selected problem, the challenges of deploying the solutions, and the host of potential technological solutions that might be arrayed to solve them. Using the Lean LaunchPad Methodology the class focuses teams to:

Deeply understand the problems/needs of State Department beneficiaries and stakeholders

Rapidly iterate technology solutions while searching for product-market fit

Understand all the stakeholders, deployment issues, costs, resources, and ultimate mission value

Produce a repeatable model that can be used to launch other potential technology solutions

National Service

Today if college students want to give back to their country they think of Teach for America, the Peace Corps, or AmeriCorps. Few consider opportunities to make the world safer with the State Department and other government agencies. Hacking for Diplomacy will promote engagement between students and the Department of State and provide a hands-on opportunity to solve real diplomacy, foreign policy and national security problems.

Like its sister class, Hacking for Defense, our goal is to open-source this class to other universities. By creating a national network of colleges and universities, Hacking for Diplomacy can scale to provide hundreds of solutions to critical diplomacy, policy, and national security problems every year.

We’re going to create a network of entrepreneurial students who understand the diplomatic, policy, and national security problems facing the country and get them engaged in partnership with islands of innovation in the Department of State. This is a first step to a more agile, responsive and resilient, approach to diplomacy and national security in the 21st century.

Lessons Learned

Hacking for Diplomacy is a new class that teaches students how to:

Use the Lean LaunchPad methodology to deeply understand the problems/needs of State Department customers

Deliver minimum viable products that match State Department needs in an extremely short time

The class will also teach the islands of innovation in the Department of State:

how the innovation culture and mindset operate at speed

how to identify potential dual-use technologies that exist outside their agencies and contractors (and are in university labs, or are commercial off-the-shelf solutions)

how to use an entrepreneurial mindset and Lean Methodologies to solve foreign policy problems

Register for the inaugural class at Stanford starting September 29th now

Filed under: Hacking for Diplomacy, Lean LaunchPad, Teaching

August 1, 2016

Hacking for Defense & Hacking for Diplomacy – Educator/Sponsor Class

There is nothing more powerful than an idea whose time has come

Victor Hugo

On September 7th – 9th we are holding our first Hacking for Defense & Diplomacy – class for Educators and Sponsors, training educators how to teach these classes in their universities and sponsors how to select problem sets and manage their teams.

Sign up here.

Sign up here.

An Idea Whose Time Has Come

Our first Hacking for Defense class was a series of experiments. And like all good experiments we tested a set of hypotheses. Surprisingly the results blew past our expectations – and we had set a pretty high bar. (see the final Hacking for Defense class presentations here). Based on those results we believe that we can do the same with Diplomacy so working with the State Department’s innovation cell in Silicon Valley we will prototype the Hacking for Diplomacy course at Stanford this fall.

A few of the student and sponsor comments about the class:

“Absolutely amazing class. Experiential learning is very effective to really grasp what we claim to know intellectually.” – computer science grad student

“One of the best classes I’ve ever taken, and it turned me onto a whole new career path.” – MBA student

“We’re still blown away what students who knew nothing about our agency could learn and deliver in such a short period of time.” – sponsor

First, would students to sign up for a class that engaged them in national service with the Department of Defense and Intelligence Community?

Result: I’ll admit my hesitancy was because I brought my memories of U.S. college campuses circa the Vietnam War (and the riots and student protests at Stanford). So I was astonished how ready and eager students were for a class that combines the toughest problems in national security, with learning Lean Innovation methods. We had more applicants (70+) for the 32 seats in this class than we usually get in our Lean LaunchPad entrepreneurship class. And early indications are that Hacking for Diplomacy will be at least as popular.

Second, could we find islands of innovation inside the DOD, the Intelligence Community and State Department willing to engage students to work on real problems? And could those sponsors work with us to scrub those problems so they were unclassified but valuable to the sponsors and the students?

Result: We solicited 8 problems for the students to work on and had to shut down the submission process after we reached 24 from the DOD. We’ve now built a national clearing house for DOD/Intel problems that other schools can use. The Department of State has already given us 15 problems for our upcoming Diplomacy class.

Third, would students be turned off by working problems that weren’t theirs, in particular from the DOD and Intel community?

Result: We surveyed student motivations before and after the class and were surprised to find that a large percentage became more interested and engaged in national service. Over half the student teams have decided to continue working on national security projects. At the end of class two teams were funded by SOCOM (U.S. Special Operations Command) to continue prototyping over the summer. One team closed a $200k seed round in the middle of the class. Multiple teams have been engaged by government, prime contractor and VC firms for follow-on discussions/engagements.

Fourth, would the same Lean Startup methodology (business model design, customer development and agile engineering) used in the Lean LaunchPad and NSF I-Corps class work here?

Result: Hell yes.

Fifth, would other schools be interested in offering this class?

Result: Seven schools have already added Hacking for Defense classes: UC San Diego, University of Pittsburg, University of Southern California, Stanford, University of Rochester, Georgia Tech and Georgetown University. 15 more schools are in the pipeline. NDU (the National Defense University) – National Security Accelerator (NSTA), the Stanford University Hacking 4 Defense Project and JIDA (the Joint Improvised-threat Defeat Agency) have all teamed up to fund the expansion of the Hacking for Defense class to other universities. The Department of Energy Advanced Manufacturing Office has also lent its support to the expansion. If our Hacking for Diplomacy goes well this fall, we intend to scale it as well.

The Educator/Sponsor Class

We learned a lot developing the Hacking for Defense class, and even more as we taught it and worked with the problem sponsors in the DOD/Intel community. Now we’ve created a ton of course materials for educators (syllabus, slides, videos) and have written a detailed educator’s guide with suggestions on how to set up and run a class along with best practices and detailed sample lessons plans for each class session. And for sponsors we have an equally robust set of tools on how to get the most out of the student teams and the university. And we’re excited it to share it all with other educators and sponsors in the DOD/Intel community.

So on September 7 through 9th at Stanford we will hold our first 2.5-day Hacking for Defense & Diplomacy Educator and Sponsor Class.

We’ll provide you all the course materials (syllabus, slides, videos) along with an educator’s guide with suggestions on how to set up and run a class along with detailed sample lessons plans for each class session. You’ll also

Meet with other instructors and problem sponsors and experience the Hacking for Defense/Diplomacy methodology first hand

Learn how to build H4D teaching teams and recruit student teams to participate

Learn what makes a good student problem and how problem sponsors can increase their Return On Investment for supporting the course

Engage with the original Stanford Hacking For Defense course authors (Pete Newell, Joe Felter and I) and students from the original H4D cohort

Engage directly with potential government problem sponsors

Life is series of unplanned paths and unintended consequences – Hacking For Defense

A year ago as I started helping government agencies put innovation programs in place, a student in my Stanford class who had served in the special forces pointed out that the Lean methodologies I was teaching sounded identical to what the U.S. Army had done with the Rapid Equipping Force (REF) commanded by then Colonel Pete Newell.

The REFs goal was to get out of the building and into the field to get a deep understanding of soldiers’ problems, then get technology solutions to these problems into the hands of front-line soldiers in days and weeks, instead of the military’s traditional months and years. The REF had permission to shortcut the detailed 100+ page requirements documents used by the defense acquisition process and could use existing government equipment or buy or commercial-off-the-shelf technologies purchased with a government credit card or its own budget.

When Pete Newell retired to Silicon Valley he teamed up with Joe Felter, another retired colonel, who had a career as a Special Forces and foreign area officer (among other things, Joe led the Counterinsurgency Advisory and Assistance Team (CAAT) in Afghanistan) and was now teaching at Stanford’s Center for International Security and Cooperation (CISAC). Together Pete and Joe had formed BMNT to create an “insurgency” in Silicon Valley to help accelerate the way the Department of Defense acquires new technology and ideas and integrates cutting-edge innovation into the organizations defending our country.

The Hacking for Defense & Diplomacy classes were born from the intersection of BMNTs work with the Department of Defense in Silicon Valley and my work in Lean Innovation.

We had five goals for the class:

Teach students Lean Innovation – the mindset, reflexes, agility and resilience an entrepreneur needs to make decisions at speed and with urgency in a chaotic and uncertain world.

Offer students an opportunity to engage in a national public service. Today if college students want to give back to their country they think of Teach for America, the Peace Corps, or Americorps or perhaps the US Digital Service or the GSA’s 18F. Few consider opportunities to make the world safer with the Department of Defense, Intelligence Community, State Department or other government agencies.

Teach our sponsors (the innovators inside the Department of Defense (DOD), Intelligence Community (IC) and State Department) there was a methodology that could help them understand and better respond to rapidly evolving asymmetric threats. (By rapidly discovering the real problems in the field using Lean methods, and then articulating the requirements to solve them, defense acquisition programs operate at speed and urgency to deliver timely and needed solutions.)

Show our DOD/IC/State sponsors that civilian students can make a meaningful contribution to problem understanding and rapid prototyping of solutions.

Create the 21st Century version of Tech ROTC by having Hacking for Defense and Hacking for Diplomacy taught by a national network of 50 colleges and universities. This would give the Department of Defense (DOD), Intelligence Community (IC) and State Department access to a pool of previously untapped technically sophisticated talent, trained in Lean and Agile methodologies, and unencumbered by dogma and doctrine.

It looks like we’re on our way to achieving all of these goals. Join us.

Lessons Learned

Hacking for Defense and Hacking for Diplomacy are classes students want

7 universities have signed up to teach it

Hacking for Diplomacy is being piloted this fall

We’re offering a 2½ day seminar for educators who want to offer either class

Filed under: Hacking For Defense, Teaching

July 29, 2016

Why the Navy Needs Disruption Now (part 2 of 2)

The future is here it’s just distributed unevenly – Silicon Valley view of tech adoption

The threat is here it’s just distributed unevenly – A2/AD and the aircraft carrier

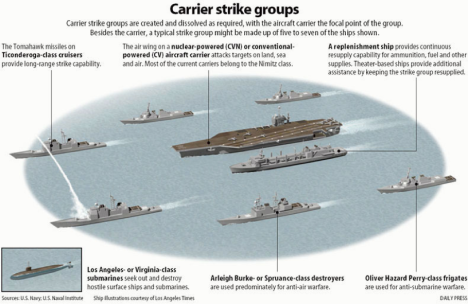

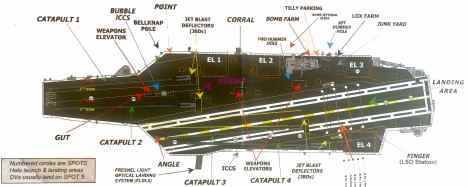

This is the second of a two-part post following my stay on the aircraft carrier USS Carl Vinson. Part 1 talked about what I saw and learned – the layout of a carrier, how the air crew operates and how the carrier functions in context of the other ships around it (the strike group.) But the biggest learning was the realization that disruption is not just happening to companies, it’s also happening to the Navy. And that the Lean Innovation tools we’ve built to deal with disruption and create continuous innovation for large commercial organizations were equally relevant here.

This post offers a few days’ worth of thinking about what I saw. (If you haven’t, read part 1 first.)

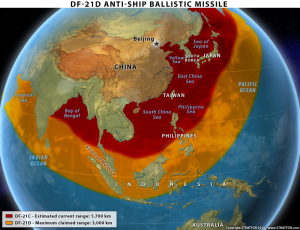

The threat is here; it’s just distributed unevenly – A2/AD and the aircraft carrier

Both of the following statements are true:

The aircraft carrier is viable for another 30 years.

The aircraft carrier is obsolete.