Victoria Olsen's Blog, page 8

January 16, 2011

Eye Candy

Requiem for a Dream (2000)

Black Swan makes more sense now that I've seen more of Darren Aronofsky's work. Requiem for a Dream (2000) explodes with so many visual pyrotechnics that it is hard to focus on anything else. The shots are beautifully composed: for an example, look at the circular frame of papers behind the characters in the shot at right and how their arms counterbalance each other. Aronofsky is attentive to every visual detail. The palette, the angles, the special effects all effectively reinforce the same drug-induced perspective that intensifies as the film progresses.

When the characters do drugs we get a flash of close ups–a flame, blood cells, pupils dilating– with a rhythmic popping to emphasize the transition to dream state. But these characters do a lot of drugs and after a while the eye candy gets tiresome, even exhausting. There is so much to look at that it's hard to think about plot or character. That may have been true for Aronofsky as well because there isn't much action or even conflict here. The characters descend into worse and worse addictions, which results in some over-the-top humiliations. Black Swan marks progress then: its nightmarish fantasy world is more grounded and there is a strong story, even if the ending is still melodramatic. Requiem for a Dream is worth seeing for its strong performances and visual creativity, but there's not much else going on.

January 12, 2011

Slow and Steady

Focus Features, 2010.

The customer reviews on Amazon for The American (Corbijn, 2010) are wildly polarized. Half of its viewers give it one star and call it "slow" and "booooring!" The other half love it and compare it to classic French film. Roger Ebert put it on his best of 2010 list, though critics mostly overlooked it. Intrigued?

The movie is indeed slow. Although it has a thriller plot (assassin is forced to lie low in a picturesque spot while his enemies hunt him down) and a few action sequences, the film moves at a deliberate, cautious pace that matches the extreme self-control of its hero, played by George Clooney. This clip captures some of the pacing and tight focus that the director Anton Corbijn uses to turn what could have been standard Hollywood fare into something visually and structurally interesting. It's a small scene, but it carries weight, as the ending will reveal. "Jack," played with admirable understatement by Clooney, is so tightly wound, so unrelentingly professional that his smallest human gesture seems momentous. The screenplay by Rowan Joffe shows this off nicely, with the barest minimum of dialogue.

The shots are just as carefully composed as the story and performances. The film begins with a broad panorama of a snowy Swedish landscape. The camera moves gradually toward a house under the trees and establishes its ground rules: no fast cutting, no hand held cameras, long takes. There are some wonderful moments of editing too — like one where a killing takes place during a cut, in the gap between shots. This is visual storytelling at its best: elegant, spare, and surprising. The American will find its audience slowly but surely.

January 8, 2011

New Endings

I'd like to inaugurate the new beginning of the year and my blog with a piece about endings. What follows is a new direction for me, but one that is continuous with my earlier readings of photographs. This year I will post short, essay-like reviews of films –some recent, some less so–that come out of my teaching, writing, and thinking about texts and images.

And now, the endings….

Endings are tricky in all sequential arts. Time doesn't stop, but the artwork must, and it must stop without feeling random. A satisfying ending should emerge from what already happened, but also extend it somewhere new. Even more than beginnings, endings point in two directions, though the signpost into the future is more of an ellipsis, a … that trails off "into the sunset." It's a precarious balancing act and the last three films I saw failed at it in one way or the other.

The ending of Inception (Christopher Nolan, 2010) neither stays consistent with its own logic nor reveals anything new. With great visual elan, the film blurs the line between dreaming and waking, creating dreamscapes that are at least as compelling and vividly rendered as the "reality" they displace. Every scene asks you to consider and reconsider which is which, and most of them force you to reverse your first assumption. And yet the film ends with a conventional return to the very reality it made us question. The hero goes home, his family and nationality are reinstated, and the world is stable again. The spinning token, the last image before the credits roll, is deliberately ambiguous: will it fall? Will it keep spinning? This was the hero's method of orienting himself in the dreams within dreams, but the ambiguity is just a coy device. We see the token start to topple at the very last second. Nolan has tipped his hand: this is real and order is restored just in time for us to leave the theater. It's a safe ending pretending to be adventurous.

credit Fox Searchlight

Black Swan (Darren Aronofsky, 2010) plays with the border between reality and fantasy too, but in a darker, more complicated way. As the ballerina heroine prepares for her role in Swan Lake the "black swan" within her self takes over the "white swan" she has shown to the world. The film, then, is about the relationship between art and reality, or better yet, between the dancer and the dance. This is heady territory and Aronofsky tackles it imaginatively and boldly. As the ballerina dissolves into her character, her performance improves and she is shown reaching a creative peak that eluded her before. Here is the film's "message," to be crass: that great art requires great risks and sacrifices. Aronofsky is too smart and creative to suggest that risk means quitting a job or sacrifice means breaking up with a lover. He insists on the necessity of psychic struggle as the source of creativity. But then, this whole complex metaphor becomes quite literal at the end of the film. The sacrifice becomes stereotypical and the film slavishly follows the plot outlines of its ballet source instead of remaining true to its own idea. It's disappointing.

True Grit (Coen brothers, 2010) borrows the framing device of its literary source,

credit Paramount Pictures

the novel by Charles Portis. It begins with a character's voiceover looking back on the events and, by golly, it will end with it too. While this structure has some advantages—it creates an organic whole, for example—it also creates problems at the end. Once the compelling central action is finished, do we care about the characters' later lives? I didn't. The tacked on "twenty years later" ending felt forced and irrelevant when the story was so complex in its own right. The ending pulls back from that complexity and misunderstands what was so absorbing about the film itself: the tension between a changing land and the fixed moral compass points exhibited by these characters. To show the characters themselves changing over time, counterintuitively, is beside the point. The ending disrupted and diffused the film's clear focus.

Despite the disappointing ending, True Grit was the most satisfying film of these three. All of them were visually breathtaking in different ways and all had gripping stories. But True Grit was the most successful at creating its own whole, complicated world, visually and psychologically. As I begin this new thread and write about endings, I'm reminded of Martin Scorsese interviewing Robbie Robertson at the beginning of The Last Waltz. Robertson said that The Band called their final concert the "Last Waltz" because it was "the beginning of the end of the beginning of the beginning." Scorsese opened his film with The Band's encore. It's a good place to end.

September 21, 2010

Ordinary Space

Alec Soth, "New Orleans, LA," 2002.

The exhibit From Here to There: Alec Soth's America, at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis until January 2, features over a hundred photographs of ordinary, eccentric Americans from all over the country. But this is the one that grabbed me. I love how understated it is, especially next to its neighbors, the large-format men and women staring straight at the camera. This subject, and this photograph, is more discreet: this woman looks back at us through...

September 16, 2010

Back in Fashion

Lillian Bassman, "Across the Restaurant."

In honor of fashion week, I present Lillian Bassman, living legend. Bassman photographed fashion for Harper's Bazaar and mentored Richard Avedon. Yet her work is more self-consciously artistic than most fashion photography and it fell out of favor after the 1960s. She left the field and threw away her negatives, but they were rediscovered to great acclaim in the 1990s. It's a great story, and her images back it up.

This one is typical of Bassman's...

September 7, 2010

Up in the Air

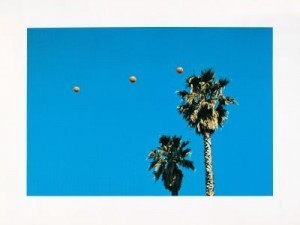

John Baldessari, "Throwing Three Balls In The Air To Get A Straight Line (Best Of Thirty-Six Attempts)," 1973

Look up. The blast of blue grabs and holds the eye, until the balls in the air direct us to the caption. The balls are almost a line of text themselves, hovering horizontally in a space with no ground. They pair beautifully with the verticality of the messier pair of trees. The simple contrasts of color, number, shape, and line are perfectly balanced: utterly still and clearly in...

August 30, 2010

Who's There?

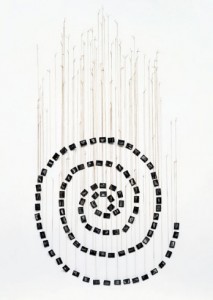

Annette Messager, "My Vows," 1990.

The incoming students at NYU's Tisch School of the Arts are being asked to visit and write about the "Haunted" exhibition at the Guggenheim before it closes next week. Although I've already written about the Casebere photograph in that show, I visited the show again yesterday in order to follow my students' exercise. They are supposed to describe a moment at the show that was particularly significant to them — a sight, sound, interaction, impression...

August 23, 2010

The Dancer and the Dance

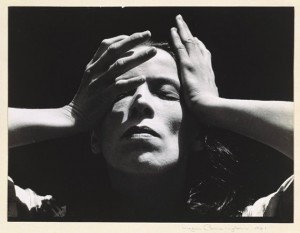

Imogen Cunningham, "Martha Graham, 1931."

The last post got me thinking about how one art represents another — as in photographs of musicians there or photographs of dancers here. In this case photography seems to submit to dance: the lighting that may have been artistically manipulated instead looks like simple stage lighting. Graham doesn't look "posed" by Cunningham, but rather in character for her choreography. Graham fills, and even exceeds, all the available space.

Yet the strong...

August 18, 2010

Hail and Farewell

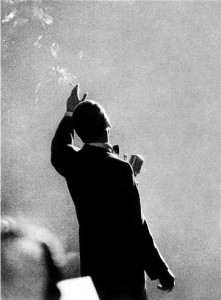

Herman Leonard, "Frank Sinatra, Monte Carlo, 1958."

Jazz photographer Herman Leonard died last weekend. His iconic photographs, including the one of Frank Sinatra at right, are said to have "caught jazz itself" and represented the "whole spirit" of his musician subjects. I get impatient with commentary like that, though Leonard's work had an undeniable signature and impact. Instead, I like the quote on Leonard's website from Quincy Jones:

Herman's camera tells the truth, and makes it swing...

August 10, 2010

The Dark Chamber

James Casebere, "Garage" (2003)

The multimedia exhibit "Haunted," on display at the Guggenheim Museum until September 6, draws on a longstanding association between photography, film, and the supernatural. From Victorian "spirit" pictures to the quintessentially cinematic genre of sci fi, new visual technologies have always been seen as literally incredible. One can't believe one's eyes.

In that context, James Casebere's photograph, included in the exhibit and reproduced here, is remarkably...