Victoria Olsen's Blog, page 3

January 23, 2014

Hit Me

Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull (1980) seems seamless. It’s special gift is its amazing wholeness — how performances and writing and directing all work together without any one overshadowing the others. Seeing it again was to notice slow, small moments tidily encapsulated in a film about rage. The short moment where Jake La Motta (played by Robert DeNiro) watches Vickie (played by Cathy Moriarty) splashing her legs at the public pool. The long moment when Jake finally approaches the ring for his championship fight and the crowd noise gets louder and louder and louder….

Watch Jake’s brother Joey, played by Joe Pesci, in the slow-building scene above: his brow creases and he shifts in his chair as he gives in to Jake’s bullying…. In many ways it’s a quiet scene, with just the two faces and no fancy camera shots, but it is portentous as Jake will continually ask for punishment from those around him and then lash out at them for giving it. The black and white cinematography helps us focus on the interpersonal here — there is nothing on the wall behind Jake until they stand up, nothing else to look at but these brothers fighting as they have and will. The radio plays on.

“What does it prove?” Joey asks a good question, and we can’t answer it yet at that point in the film. The scene is all suggestion — that fighting begins at home (notice the woman, Jake’s wife, with whom he has already fought, peeking through the door?) and that Jake’s inability to divide public and private, fighting and family will escalate the suffering around him. The film is best known for its operatic violence, its spraying blood and pulpy faces, but these quieter bits are just as impressive.

January 12, 2014

Truly Free

In the clip above from Happy People: A Year in the Taiga (2010) Werner Herzog narrates the lives of Russian trappers in the remote wilderness on the edge of Siberia. His inimitable grave voice battles the sentimental soundtrack as Herzog tells us that these men, who spend months each year alone with their dogs, are self sufficient and thus “truly free.” The documentary, directed by Herzog with Dmitry Vasyukov, is wonderful — beautifully photographed and obsessed as only Herzog can be with the details of the trappers’ lives: sculpting canoes, hauling gear through treacherous waters, protecting food from bears, making their own skis…. The men are impressive craftsmen, and they can make whatever they need from the materials at hand. Living in a land only accessible by boat or helicopter for a few months a year, they have snowmobiles and television sets, but rely on food they grow or catch.

It’s no surprise that Herzog would romanticize this life as he has always been interested in the relationship of man and nature, especially in extremis. This film has the usual omissions: the men spend more time talking about training their dogs than raising their children, for example. Women are scarcely mentioned, nor are the ethics of the fur trade, tensions with indigenous peoples, or environmental concerns. But Herzog’s narration is more understated than in Grizzly Man, for example, where he makes more claims about Human Nature as well as Nature and Civilization. Here he only once or twice refers to his claim that the trappers are “happy people” because they live simple, self-sufficient lives….To his credit, Herzog doesn’t spend a lot of time defending that position. Instead he dramatizes the daily lives of the trappers across the seasons, showing us their enthusiasm for their work as the best proof possible. One trapper hardly stops smiling, even when a fallen tree caves in the roof of his hut. They may be happy, but these men are always one small step from disaster, it seems — which makes the film much more complicated and rewarding than the title might imply.

January 5, 2014

Can You See the Real Me?

There was so much to like about American Hustle (2013)! The performances by Christian Bale, Amy Adams, Bradley Cooper, and Jennifer Lawrence were all strong in subtle ways. The story by Eric Singer and David O. Russell–about an improvised sting operation run by a rogue FBI agent with two ex-cons– was terrific. And David O. Russell’s direction was assured and well paced. The clip below shows his mastery of visual storytelling as it gradually reveals the couple’s relationship and the film’s theme of pretending. The screenplay continually questions what or who is “real” and in this strange but moving dress-up scene we paradoxically see this couple as themselves– falling in love in a dry cleaner’s store as the plastic-wrapped clothes encircle them in a world of their own.

Yet as a whole the movie didn’t cohere for me. I wasn’t sure where this messy engaging story was going, which was part of the point of the twists and turns of the plot. But what was the main focus or idea of the film? Irving (Christian Bale) and Sydney (Amy Adams) learning how to be real with themselves and each other? The conflicts that occur when one person’s reality clashes with another’s? The failures that spring from good intentions? There are lots of ideas played out here, but no clear focus to the whole–which is a shame because the parts are so good.

October 6, 2013

La mort

It took many tries to view Amour, Michael Haneke’s Oscar-winning foreign film from last year. After I found a friend willing to watch a film about death and aging we then spent several weeks trying to coordinate schedules so we could watch it on demand one evening. I promised to provide sugar to cheer us up, and tissues. He and I had both been on the front lines for the death of a parent and we were going out of our way to revisit that time–

The clip above shows some of the film’s stately pleasures: Haneke’s slow pace and his patience in letting a small but telling scene unfold itself (I read somewhere that the pigeon scene took 12 takes), his attention to lovely visual details like the patterned floors in both rooms and the shadows and light at windows and doors. Most of the scene is quite static. The camera doesn’t move and there are few cuts. We see the old man (played by Jean-Louis Trintignant) struggle with the pigeon from a distance and the comic element gradually becomes heroic. As viewers and writers we’re supposed to ask questions like “what does he want?” but even the question seems grotesque in this context. He wants the love and intimacy he lost: nothing that a pigeon could provide! My friend and I sobbed through much of the film, but the old man doesn’t cry. He reminds me most of Virginia Woolf watching that moth: there’s life itself right in front of her! (…then death, of course) The old man wants to reach out and grasp life too, but he is already failing. Death is such an abstraction so much of the time that I found it oddly reassuring to watch it unfurl on the screen and remember it unfurling in my father. It is a tremendously brave film.

September 29, 2013

Rain Man

It must be difficult to film a new and surprising martial arts sequence. In the long history of the genre and its films, hasn’t everything been tried already? The first scene in Wong Kar Wai’s new film Grandmaster (2013) manages to feel fresh though: although using atmospheric elements and a restricted palette have been done, Kar Wai spends as much time on the water as the battling men. The rain becomes an active participant in the fight– striking with force, spinning through the air, bouncing off targets. Although the melee is hard to make sense of because of the choppy editing and the darkness, it is a visual treat that sets up a film full of visual treats.

I went to see Grandmaster with someone who didn’t like it. There is no consistent story with suspense or drama. The characters are one-sided. The ending sentimental. All true. But where else can you see a close up of an exquisitely-lit coat button? Recurring patterns of feet sliding and pivoting on the floor? The attention to sensual detail (and moody cinematography) are typical of Kar Wai’s films and he arranges his moving canvas carefully. There are long swathes of gold in a brothel , then a shift to an all-white winterscape. There are brief cuts to archival footage from Chinese history in the 1930s and 1940s. Text appears on screen to move the chronology along. The film is based on the historical figure of Ip Man (played by Tony Leung), a martial arts master who trained Bruce Lee, but Kar Wai doesn’t always seem sure if he is making a biopic, a romance, a kung fu flick, or even a documentary about the varieties of martial arts in China. Nonetheless, I found the film beautiful enough to forgive many flaws.

September 22, 2013

Lenses

I have the impression that most literary types didn’t like Baz Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby this summer…. but I enjoyed it. I liked the super-saturated colors, the dizzying camera angles, the speeding cars, the glamorous costumes, and the anachronistic music…. I love it when the man in the pink suit explodes into violence (see below). I love the book too, but they are two different animals. As Daisy tells Jay, “this world is made entirely out of your imagination,” and that’s what both book and film pull off. That willed act of imagination is the essence of the novel that any adaptation should try to get right, and Luhrmann has the gift. Like Gatsby, like Fitzgerald, Luhrmann dives in to his story wholeheartedly and believes in what he has made. I think the film’s attempt to show some background by cutting to Gatsby’s dustbowl childhood and war service was a mistake for the same reason: it should stick with the fictions and leave the “reality” for us to imagine. Does the film represent the book? It interprets it — as it is supposed to, through Luhrmann’s extraordinary lens.

September 15, 2013

Two Worlds

Here’s a strange contrast: this weekend I watched Jane Eyre (directed by Cary Fukunaga, 2011) and Elysium (directed by Neill Blomkamp, 2013). Elysium is explicitly about two worlds — one for the haves and one for the have nots– but that idea was first popularized by the Victorians, so maybe that can be the point of comparison to bring these two seemingly unrelated films together. I often find film adaptations of Victorian novels to be unconvincing. Either they sentimentalize or they exagerrate. This Jane Eyre was persuasive though, in part because of Mia Wasikowska, who played Jane with understated emotion. Charlotte Bronte’s Jane is a volcano, with all the emotion suppressed by long habit and self denial. The novel begins with a scene of child Jane erupting into fury at an injustice done her. The film reorders the events and begins with a distraught and wild-looking adult Jane stumbling through a rain storm. Although the film scene emphasizes Jane’s distress over her anger, the revision works because it still introduces us quickly to Jane’s real, volatile self and then proceeds to flash back to the causes of her upset. Similarly, listening to Jane’s conversation with Edward Rochester (also well played without exagerration by Michael Fassbender) in the clip above we can well imagine why he fell in love with her, despite the social status and other obstacles that should have prevented it. No one could have ever spoken to him in that clear, honest voice before. Jane tells the truth, and it makes her free. In extreme contrast, here is a scene from another world, Earth 2154, where regular dirty ethnic people live while shiny clean white people hover above them on an exclusive satellite called Elysium. Here is a clip of a typical fight sequence: The use of slow motion and silence to punctuate the action works well, but it’s still just a well executed battle. The film’s art direction was just as wonderful as in Blomkamp’s District 9: the same cluttered frames overflowing with trash and graffiti tags. This earth is sterile, but Elysium, in its white cleanliness, is eerily empty. Matt Damon, as our proletarian hero Max, is as likeable as ever, but Jodie Foster as the cold-hearted politician is surprisingly wooden. The flaws in the screenplay are most evident in her stilted dialogue, and she makes even paradise seem unappealing. For stories of social transformation, I’ll take the Victorians, and for worlds, I’ll stick with Earth.

September 7, 2013

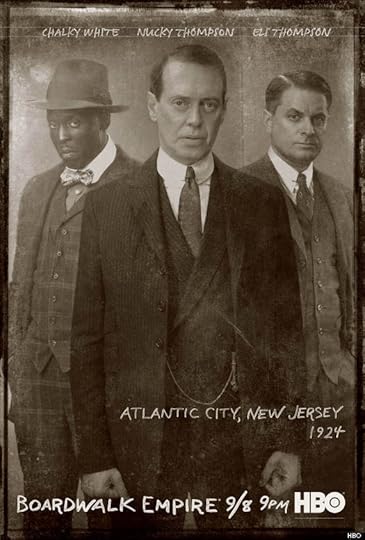

Back to Atlantic City

HBO’s Boardwalk Empire has a penchant for killing off popular and likeable characters and we lost both the good (Owen Slater and Billie Kent) and the bad (Gillian Darmity and Gyp Rossetti) in season 3.

For season 4 the publicity machine is already promoting new characters played by Jeffrey Wright, Ron Livingston, and Patricia Arquette. But what caught my attention the most in the media flurry leading up to Sunday’s new season premiere were the beautiful photographs made to resemble the wet collodion process from the 1860s and 1870s. By the 1920s the process was already out of date, historically, but these sepia-colored posters with their faded images, uneven tone, and visible scratchs give a wonderful sense of the period anyway. They evoke the WANTED posters of the old West, appropriately enough, but also the full-frontal portrait styles of daguerreotypes and tintypes. Labelled by hand, the images look torn from a family album — reminding us, perhaps, of how intimately we know these characters now.

[For another version of this photographic style and process, see the Julia Margaret Cameron exhibit now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through January.....]

August 31, 2013

Look Here

It’s easy to describe Gregory Crewdson’s photographs: eerie, static, theatrical, disturbing….Edward Hopper meets David Cronenberg. In his documentary Gregory Crewdson Brief Encounters (2012) Ben Shapiro does a marvelous job of letting the work reveal itself. He focuses mostly on the production process, then stops his film to let the resulting work fill the screen so we can look deeply. The photos themselves are like film stills, as everyone notes — in part because of the intense stage-setting that Crewdson demands and in part because of their sense of drama. Crewdson calls them “frozen moments,” but he doesn’t seem interested in the rest of the story they suggest. The images exist in a sort of airless vacuum outside of time and narrative, though in specific, highly elaborated spaces.

The documentary shows Crewdson overseeing every detail of finding locations, constructing sets, posing figures, setting lights, and anxiously watching over the weather. He seems something of a control freak, but that’s what makes the work so vivid, intense, and beautiful. I love the singlemindedness of his scouting — looking, looking, looking. He doesn’t bring a camera or seem to take notes as he roams Western Massachusetts for settings. He just immerses himself completely in what he sees.

His attention to detail recreates the visions in his head, which is why the photographs can seem “psychological,” in his words. But to his credit he doesn’t spend too much time explaining or justifying them. The image above that opens the film’s trailer is both scary and luminous. It stands on its own merits without the film or a caption or any particular context. We don’t know what has happened in that room, or why, but does it matter? We could talk about Ophelia– or we could just admire the glowing greens and yellows reflected in the dark water.

August 20, 2013

Our House

The House I Live In (2012) , directed by Eugene Jarecki, is a moving documentary with such a strong argument that it may be easy to miss the art that also went into it. Jarecki makes an admittedly opinionated case that the “war on drugs” is the cause of the overflowing prison population that disproportionately affects African-American communities in the United States. He is not the first to make this case, but the documentary form is uniquely powerful in representing it. Jarecki interviews a broad swathe of people–from law enforcement officials to scholars to prisoners– and often gets unpredictable responses. The police officer who has changed his mind about drug laws. The judge who regrets his sentences. The African-American sociology professor who made it out of his drug-damaged community only to find his son swept into it. Jarecki makes it clear that there are no safety nets for people who make bad decisions, and three strikes means there are no second chances….

Alongside the typical talking heads, though, is Jarecki himself, who narrates the film as a personal journey to understand the story of his African-American housekeeper, Nannie Jeter. The relationship between the white Jareckis and black Jeter family is naturally complicated: like many other women of color, Jeter moved away from her own children in order to care for the three Jarecki boys, and she blames her own son’s drug problems on her absence. Her pain — and Jarecki’s privilege — is excruciatingly obvious, but Jarecki avoids both sentimentality and defensiveness. The families are closely connected, but their prospects couldn’t be more different. Jarecki is brave to expose his own indirect participation in the war on drugs, and turn it into direct action in the film. His presence, and Jeter’s story, motivate and unify the otherwise broad canvas.

Perhaps Jarecki’s film is not just an agent of change but a sign that it has begun. The recent federal decision not to enforce mandatory drug sentences is promising, even with its limitations. The film is a call to action and consciousness-raising: Jarecki insists that we all have to live in this house and we are all responsible for these tragedies.