Victoria Olsen's Blog, page 6

October 10, 2011

It's a Metaphor

credit Columbia Sony Pictures 2011

My students are writing their first papers of the semester now and struggling with Mark Doty's essay "Souls on Ice," in which Doty describes metaphors as "containers" for emotion, or tangible vessels for intangible ideas. This definition functions much like metaphors themselves: making the complex simpler, if not simple.

Baseball, of course, is a game made for metaphors, and Moneyball (2011) is full of them. In one of the last scenes of the film, the Oakland A's assistant general manager (Jonah Hill) tries to show the general manager, Billy Beane (Brad Pitt), that some experiences that may feel like failures are really successes. He shows a great clip (is it from a real game?) of a baserunner scrambling to get to first base, then belatedly realizing he had hit a home run. There's a pause until the Jonah Hill character says "it's a metaphor." Billy/Brad, exasperated, says "I know it's a metaphor!" and we have to wonder what isn't a metaphor in this idea-driven film. The poster at left, with its tiny figure on the great green grass, puts the main idea on display: how much difference can one man make in a giant system? or, as the slogan puts it, more commercially, "what are you really worth?" The smallness of Pitt's figure seems to be in ironic juxtaposition to the huge black letters of his name, which tell us exactly what he's worth.

The movie, directed by Bennett Miller from a book by Michael Lewis, is admirably cautious in answering these questions. Since historical narratives like this one can't really have "spoilers" I feel safe in saying that Beane does make a difference to the old established ways of running baseball teams, but he still isn't exactly victorious. The big questions asked in the film– how do you evaluate talent? what is your biggest fear? what does it mean to win or lose?– are only sketched, not reduced to glib cliches. It's refreshing to see a film so comfortable with complex ideas and so ready to grapple with them respectfully. In that regard this film reminds me of Miller's last, Capote, which did an equally good job of rendering abstractions on film.

The idea that drives Doty's essay is very similar to the tentative conclusion that Miller gives us as well: "our metaphors go on ahead of us…" and they know more than we do.

August 15, 2011

Eden, Texas

I enjoyed The Tree of Life (2011) more than the people I saw it with. I agreed with them that Terrence Malick's latest film, which won the Cannes d'Or, didn't succeed in fully integrating its parts. The beginning and ending were surreal or abstract representations of cosmic states, whereas the middle was a relatively realistic portrayal of a particular 1950s family in Waco, Texas. That family, supposedly based on Malick's own, suffers a tragedy which links it to some universal experience. But the film does not make it clear how the particular and universal are linked. We each had different opinions about what worked and what didn't, but for me the middle, the family's story, was both beautiful and compelling.

Here's a scene from the middle that is particularly beautiful and effective. The father, played by Brad Pitt, takes a business trip and we watch the rest of the family uncoil from his repressive presence. It's as if a rubber band snapped: the camera pans around the rooms following the careening children who jump on beds, slam doors, and laugh and shout. It's especially moving because the mother joins them….

[There is a video that cannot be displayed in this feed. Visit the blog entry to see the video.]

"Where were you when I laid the foundations of the earth… When the morning stars sang together and all the sons of God shouted for joy?"

The film uses this biblical text from Job to remind us of the joys and beauties that we too easily forget, though they are all around us. These resurrected childhood memories are lost just as the pleasures of childhood (the intense emotions, the vivid sensations) are lost, just as Eden is lost. The film's title and insistence on spirituality is less about finding an actual god, though it often seems to be addressing one, but rediscovering that spiritual appreciation within oneself. Jack looks back on his childhood as if it is a dream-like state of the unconscious and begins to recognize that his brother's death makes that pre-lapsarian idyll all the more precious. The joy was not just in contrast to the tragedy that followed; rather, joy and struggle are inextricably connected, as the quote suggests. This realization allows Jack to forgive and be forgiven by his stern father and it allows him a reunion at the end with his hallowed mother.

There is plenty to criticize about this film–the overbearing voice-over, the generic characters, the lack of narrative, the dinosaurs–but in keeping with the film's ambitious scope and its own effort to find the good and the beautiful, let's focus on the positive. We should celebrate Malick's courage in putting this personal and idiosyncratic vision out there, though it may have trouble finding a receptive audience. Malick takes a big risk when he hedges between the personal or autobiographical narrative and the universal or metaphorical. This film lands awkwardly between the two poles, perhaps, but it was worth the leap.

August 10, 2011

Waaaay Beautiful

The title of Peter Weir's last film, The Way Back (2010), is misleading. It suggests that the extraordinary journey of a handful of escaped prisoners from Siberia to India is all about returning home to something. And "way" is a wishy washy noun that is easily confused here with its jocular adjective: WAAAAY back! It's unfortunate.

The beginning and ending of the film do suggest this banal faith in home and the people in it, but the film quickly moves on to more interesting matters, visually and narratively. The clumsy first and last scenes, in which some cliched plot points are given some rapid exposition, could be deleted without damage to the wondrous middle. There Weir allows his camera to veer off track again and again, while reinforcing a narrow storyline. The plot is simple: the inmates escape, suffer harrowing deprivations, and reach their goal. They lose the usual number of characters along the way, with the usual sentimental effect. The geography seems divinely designed to test and torment them: they walk from Siberia through the Mongolian desert to Tibet and the Himalayas. By the time they get to the Himalayas even Weir seems exhausted: that part of the journey is reduced to a few minutes of montage.

[There is a video that cannot be displayed in this feed. Visit the blog entry to see the video.]

Yet by then we've been hooked– by the glamorous scenery in part, but also by the beauty of the visual storytelling, as Weir moves from exquisitely composed longshots to tramping feet. He deftly gives a sense of the enormity of the journey and its personal costs by shifting scales and rhythm regularly. He lets his camera stumble along with the characters, as you can see in this quick, rough scene. It begins with a slow pan across the ice then dissolves into a chaotic tumble of cuts and handheld mayhem. It's giddy with pleasure in running, breathing, being alive. In this and other scenes Weir reveals how nature and humans can sometimes be in sync, both bursting with vivid life.

July 24, 2011

One Too Many

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, part two (Warner Bros, 2011)

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, or number 7, part two, is a film with many endings. I'm sure it has at least seven if you count all the signs of finish: a death and resurrection, villains vanquished one by one, a battle won against all odds, the reappearance of favorite characters from early in the series, many well-arranged group shots, and plenty of cameras panning out and away from Hogwarts, our home away from home this past decade. And then there's the epilogue "19 years later"….

In short, the poster that claims "it all ends," and the media waxing nostalgic, may be premature. The merchandising machine lives on. If I sound impatient it is because I wanted to enjoy this film, as I have enjoyed several in this series, including Deathly Hallows part one– but I found it impossible. The cutting of the last book into two films leaves this piece almost incomprehensible — a rush of action sequences with few connecting emotions. The direction, again by the usually adept David Yates, feels aimless — as if all decisions were made by a committee of marketing managers who needed the camera to pan past Cho Chang one more time so viewers remember where Harry began. Scenes that should be suspenseful, like characters saved at the last second, just seem repetitive. And there are too few moments of pure glee or mischief–like when Professor McGonagall (Maggie Smith) giggles"I've always wanted to use that spell!" at an otherwise dark moment.

The sheer overflow of fun that was one of the charming features of the books and earlier films feels forced: instead of the exuberant variety we're used to we get the "gemino" spell which multiplies everything one touches into more of the same. Many of the most climactic scenes do indeed seem to be pastiches of bits from Lord of the Rings, Indiana Jones, and other former blockbusters. In the scene below in Gringott's bank Harry enters a dark cave and must distinguish the "authentic" object from the copies, just as Indiana Jones must do in The Last Crusade, part of a series that was itself a parody of adventure films. The scene both expresses and contains our ambivalence about overbundance and uniqueness: if this is art, shouldn't it be special and unique? but if it is to make money, and be loved my millions, shouldn't it be mass produced? Voldemort, who has divided his soul into pieces, shows how unsustainable that paradox is.

[There is a video that cannot be displayed in this feed. Visit the blog entry to see the video.]

Overall, the film is more predictable than terrible, but that was disappointing. By its end it is broadcasting shamelessly: the screenplay requires characters to say that the dead "are still here," thumping their hearts, not once, but twice. As Ron says above in one of the movie's many self-referential bits, "you're seriously going to try that one again, are you?" It asks Harry to have faith in love, and its characters to have faith in Harry, but the film has little faith in its viewers.

July 11, 2011

Slow Motion Picture

The clip above is a good representation of its film, Sweetgrass (2009): slow, deliberate, and beautifully shot. The artistry is apparent, but the filmmakers, Ilisa Barbash and Lucien Castaing-Taylor, have the good sense to make the "story" subtle. As in this excerpt, the documentary is not narrated or prefaced or even introduced except through these lingering images. Although it risks losing its audience, the strategy works by forcing us to pay close attention to what we see and hear. The quizzical expression on a sheep's face. The sound of birdsong. The wind ever-rustling.

There is in fact a story here about change and motion, but it is told through stillness. Montana cowboys have driven their sheep to pasture in the Beartooth Mountains for decades, but the film documents the last run in 2003. As a documentary Sweetgrass is unsparing and unsentimental: it cuts from a silhouetted Marlboro man standing on a ridge to a foul-mouthed cowboy cursing out his sheep.

Barbash and Castaing-Taylor like to disrupt our assumptions about nature and the West. They linger on broken landscapes like the ones that begin this trailer, where lines cut across and interrupt the picturesque and sublime. There is beauty here, they imply, but don't take it for granted.

The sheep themselves can surprise too. At the end of the trailer they transform from a few stragglers to a shifting abstraction that moves as one. In a breathtaking shot later in the film we see a shadowed mountain across a green valley. As the camera slowly moves closer we make out a line of white trailing down its side. Then the line of white appears to move. Then we see that the white line is actually hundreds of sheep making their way down the cliff. The mountain that seemed so motionless was never still at all and the camera's slow motion made us see it (and the sheep) afresh. The filmmakers' restraint is admirable: they let the story tell itself and its structure emerges organically from the material. They show a remarkable confidence in their own vision and judgment, and they earn it.

July 4, 2011

Love is Not Enough

Many people I respect a great deal recommended I Am Love (2010) to me. Directed by Luca Guadagnino, the film introduces us to an upper-class Italian family undergoing generational shifts. The opening credits glide through exquisite black-and-white shots of Milan under snow, which quickly establishes an emotional and aesthetic tone. The dinner scene that sets up the theme is elegantly concise and restrained. In a few virtuoso strokes, Guadagnino reveals the complex relationships within the extended family. Gradually it becomes clear that this is Emma Recchi's story. Carefully played by Tilda Swinton, this wife and mother has forgotten who she is: her name, her origins, her language, her feelings have all been buried under her married life. Predictably, she (and the film) will move from the shadows toward color and warmth, as a stereotypical thawing occurs under the Mediterranean sun. The premise is cliched, but that's okay since the execution is so beautiful. Guadagnino's camera lingers on softened window reflections and pans across hazy mountain vistas. If only the understated performances and lovely cinematography were enough!

I'm posting the trailer because it displays my sense of the whole film as a series of beautifully shot set pieces that don't ever become an engaging story. The rapid cuts and accelerating music seem a substitute for real suspense. As the characters become more themselves, the stakes grow higher and the film rises toward a melodramatic crescendo that does not seem justified. Perhaps losing the restraint of the film's beginning is the point, but by the end Emma, and the film itself, has broken free of coherence as well as conformity. The film's subplot about the fate of the family business is left unresolved just as many relationships are left dangling. Guadagnino implies that all we need is love…but art, at least, needs more.

June 13, 2011

The King's Body

I put off seeing The King's Speech, multiple Academy Award winner and costume drama, for as long as possible. It seemed predictable: of course the awards, of course the triumph over adversity, of course the colorful eccentric Brits, of course the rich are just like us after all….What could it tell me that I didn't know already?

A few surprises. First, the story itself was economically and deftly told. The plot may be high melodrama, but director Tom Hooper manages to leave enough space between scenes and within conversations that the film doesn't feel overstuffed or overdetermined. More surprising, though, was Hooper's visual experimentation throughout the film. In this award season The King's Speech seemed always to be the conservative choice, the traditional film, that would win because it didn't take risks like its flashier competitors The Social Network or Inception. But Hooper is just as daring a filmmaker despite his traditional material. Watch the film clip above. See how often Hooper cuts between two centered figures against spare backdrops? The Duke and Duchess of York huddle together on a couch; the speech therapist Lionel Logue towers over them, shot from below. Hooper cuts quickly back and forth between them, conveying their "equality" (a word Logue emphasizes in their work together) and their inequalities at that point in the screenplay.

But this static comparison soon breaks down: next we see the therapeutic work itself. The Duke and Logue facing each other, again centered in the frame, and shaking their heads madly. The Duke swings his arms in great circles. He rolls on the floor, filling the frame from right to left. The Duke jumps over and over close up to the camera, his head often leaving the frame. It's as if Hooper is trying to explode the cinematic space in front of us, just as Logue is trying to relax the royal body. Despite its title, this film relies heavily on body language and visual composition to make its points. The dialogue in this scene is almost unnecessary, though delightful. Hooper and screenwriter David Seidler (one of the film's Academy award winners) use speech and voice as metaphors for identity throughout the film, but here it is metonymic too: the voice as the self. It is an important reminder that a voice belongs to a body and that the best healing treats the whole.

May 19, 2011

Their Corner

The Fighter (2010) presents as a classic ensemble film: with two well balanced male leads (brothers Micky and Dicky, played by Mark Wahlberg and Christian Bale) and two equally balanced female leads (Micky's girlfriend and mother, played by Amy Adams and Melissa Leo). The film, directed by David O. Russell, generously shares its attention and sympathies amongst these accomplished actors, who made the film a success. But at the end of the day, the film doesn't show us much that we haven't seen many times before. The against-all-odds boxing victories, the dysfunctional family made whole, the girl who believes in our underdog hero, the junkie made good…. The plot, the characters, the setting, even a lot of the dialogue felt well worn. The film was saved by its outstanding performances.

still from The Fighter (2010)

And by a surprisingly fresh cast of supporting characters in Micky and Dicky's six sisters. These generic women functioned as a single entity through most of the film, providing running commentary on their brothers' lives and Micky's new girlfriend, Charlene. With their cut offs and foul mouths, they are fierce and ridiculous, protective and cruel. They seem to have no lives of their own.

The film uses them to great effect. Squeezed onto a long sofa in the family living room, they provide a flanking gallery for the scene where Micky confronts his mother and brother about mismanaging his career. The camera cuts from Micky and Charlene, huddled on a sofa of their own, to the united mother and brother. But it occasionally cuts to the sisterly chorus against the third wall. With crossed arms and shrill voices, they speak as one against Micky's new girlfriend: "MTV girl!" "Skank!" There is something harpie-like about them. By the end they are vanquished, in a cat fight of course, but they remind us of where Micky is coming from and what he needs to leave behind. In this scene Micky starts to become a fighter.

May 9, 2011

Dreaming Man

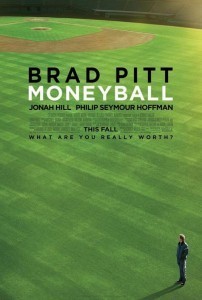

Chauvet cave painting

You may not understand Cro Magnon man from Werner Herzog's Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010), but you will understand something about the director and his preoccupations. Herzog's new documentary shows us the inside of the Chauvet caves in southern France, where prehistoric paintings were discovered in 1994. Herzog was granted exceptional access to the fragile site, and in return he gives us an exceptional, personal portrait of it. The art work is extraordinary– with animals depicted mid-motion with a sure line and delicate shading– but the story is almost more so. These images were created 30,000 years ago when our ancestors were still sharing the earth with Neanderthals. This cave survived intact because of a rockslide that effectively sealed it off for tens of thousands of year. None of this is explained in any detail in the film, nor do we learn exactly how the images were made or how they compare to other prehistoric cave paintings. But Herzog does a great job of using them to fuel his usual obsessions: the definition of "human," the nature of the soul, and man's relationship to nature. Against the anonymity of these "forgotten" artists he sets the individuality of the scientists and researchers now studying the work. They are typical Herzog eccentrics: one wears an animal skin on camera to show how Cro Magnon man may have dressed; another plays "The Star-Spangled Banner" on a prehistoric flute. It's easy to fall for their passion for this cave and Herzog is quick to draw out its essential mystery. We can't know these artists– despite the tantalizingly intimate handprints left on a wall. We can't know their world– despite 3-D imagery, carbon dating, and computer modeling. The very technology that enables the documentary still fails to account for the art. Early in the film Herzog points to the repetitive images of horses and bison and speculates that they are moving images, a kind of "proto-cinema." If so, Herzog himself is an artist like the nameless Cro Magnon artist of the caves: he shares with us his dreams of meaning and beauty.

May 1, 2011

All the World's a Garden

From beginnings to endings now, as the semester closes down.

The Constant Gardener (2005)

This image is from the ending of The Constant Gardener (2005), directed by Fernando Meirelles. Though it's hard to talk about endings without spoilers, it doesn't give away too much to say that the protagonist of the film, Justin Quayle (Ralph Fiennes), is the constant gardener of the title, taken from the book by John Le Carre. At the beginning of the story Quayle is a diplomat in Kenya who seems to insulate himself from a complicated world by creating and tending beautiful gardens. He has taken Voltaire's advice to "cultivate your garden" quite literally, but it doesn't protect him. His world is interrupted by tragedy when his activist wife is killed in mysterious circumstances. The rest of the story is Quayle's "search for the truth" in dramatic terms, but it soon becomes more existential than that. In order to figure out what happened to his wife, Quayle first needs to understand the world better, the world that his wife immersed herself in. The film is really a tale of his re-education, or awakening, into a fuller consciousness. Of course, this means he becomes conscious too of what he has lost — his wife, but also some innocence and contentment. The implications of this shift are not all clear from the film, in which Quayle remains a discreet and private figure. But the change itself is complete–Quayle grows in his capacities to love, to sympathize, and to suffer. The world is now his garden. It is this transformation that is on view in this image, from the last scene of the film. Now alone with the truth, he can wait for his fate with a moral courage he earned along the way. Far from home and far from his garden, in this barren and beautiful landscape, he whispers his wife's name.