John Bengtson's Blog, page 27

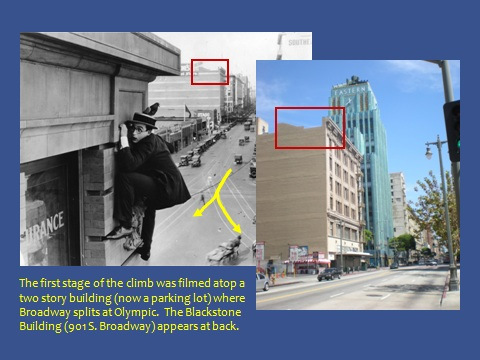

February 7, 2013

How Harold Lloyd Filmed Safety Last! (update)

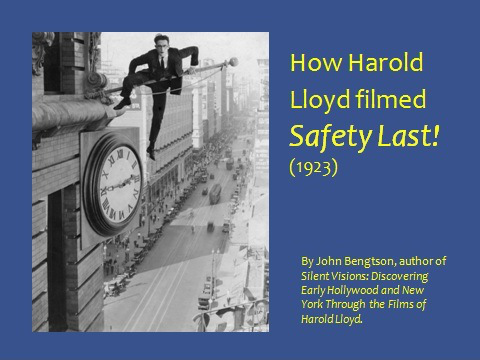

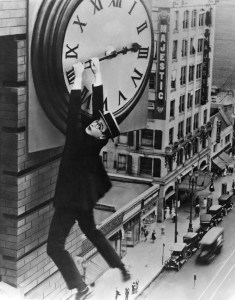

The image of Harold Lloyd clinging desperately from the hands of a skyscraper clock during Safety Last! (1923) is one of the great icons of film history. Last year’s multiple Oscar-winning movie Hugo (2011) pays tribute to Safety Last!; first by including a clip of Harold’s film within the movie, and again when the young hero Hugo Cabret finds himself hanging from the hands of a clock at the train station where he lives. Even the poster artwork for Hugo mirrors Lloyd’s earlier film.

The image of Harold Lloyd clinging desperately from the hands of a skyscraper clock during Safety Last! (1923) is one of the great icons of film history. Last year’s multiple Oscar-winning movie Hugo (2011) pays tribute to Safety Last!; first by including a clip of Harold’s film within the movie, and again when the young hero Hugo Cabret finds himself hanging from the hands of a clock at the train station where he lives. Even the poster artwork for Hugo mirrors Lloyd’s earlier film.

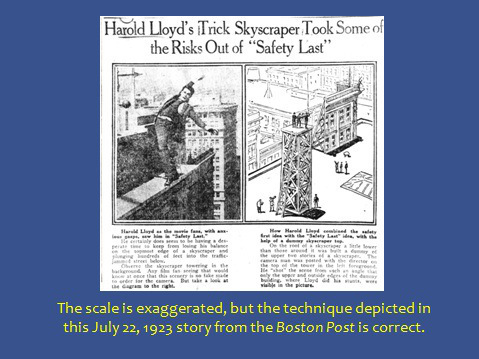

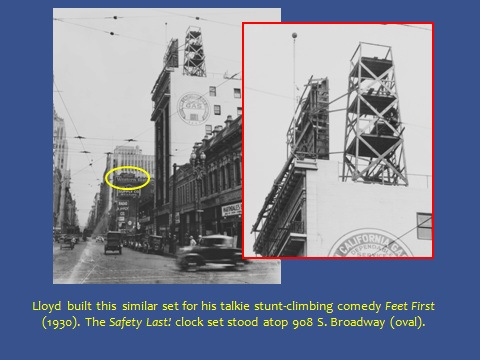

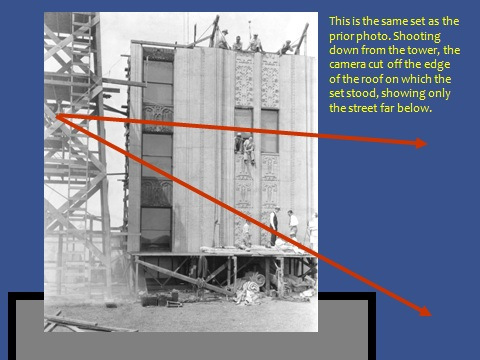

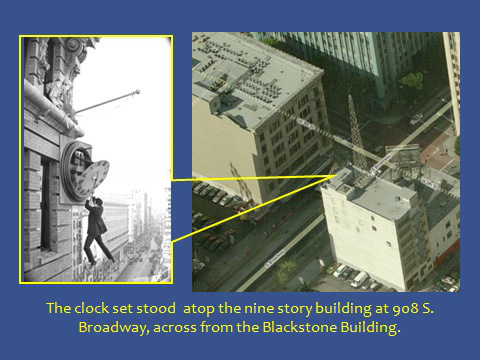

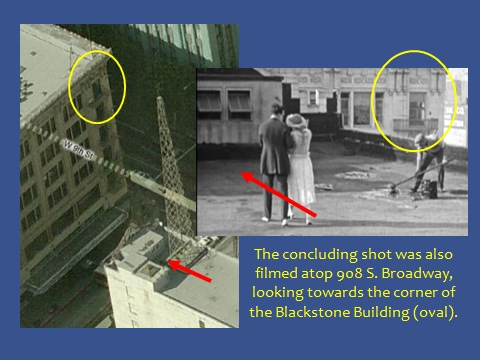

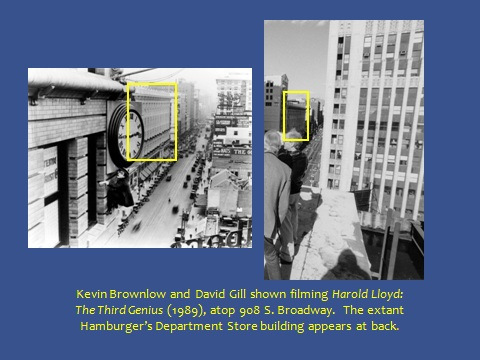

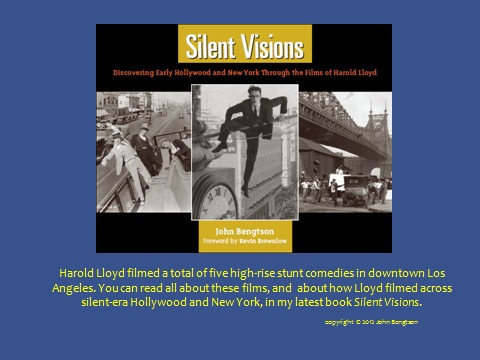

Filled with maps, aerial views, and vintage photographs, my book Silent Visions devotes 47 pages to detailing how Lloyd filmed Safety Last!, and his other stunt-climbing comedies (Ask Father (1919), Look Out Below (1919), High and Dizzy (1919), Never Weaken (1921), and Feet First (1930)) within the downtown Los Angeles Historic Core, while highlighting the burgeoning Los Angeles skyline appearing in the background of these films. The following slides provide a brief overview, and may be downloaded further below as a 14 MB PowerPoint presentation.

Here is the link to download the PowerPoint. Most of the slides are animated, so wait a moment each time before clicking the “next” button.

Hugo (C) 2011 Paramount Pictures

How Harold Lloyd Filmed Safety Last by John Bengtson

You will need a PowerPoint viewer to watch the show, and can download a PowerPoint viewer at this site.

I am also posting here, once again, a self-guided walking tour of the downtown Los Angeles locations Harold Lloyd used in Safety Last!, along with locations from Never Weaken and Feet First.

You can also check out my other posts about Safety Last! here.

HAROLD LLOYD images and the names of Mr. Lloyd’s films are all trademarks and/or service marks of Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc. Images and movie frame images reproduced courtesy of The Harold Lloyd Trust and Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc.

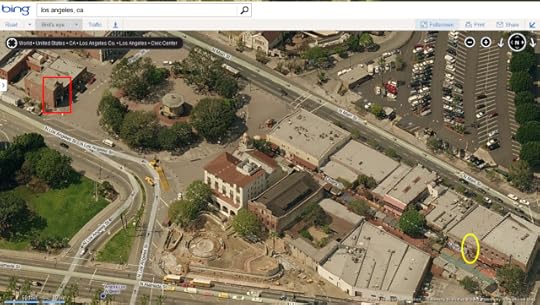

The site of the clock set, above, at 908 S. Broadway on Google Maps.

View Larger Map

Filed under: Harold Lloyd, Lloyd Thrill Pictures, Los Angeles Historic Core, Safety Last! Tagged: Broadway, Feet First, Harold Lloyd, Hugo, Lloyd Thrill Pictures, Los Angeles Historic Core, Man on the Clock, Safety Last!, Silent Comedians, Silent Comedies, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, Stunt Climbing, then and now

January 26, 2013

Keaton – Wings – Noir – and the SP Depot

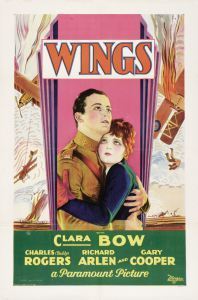

Wings, a 1927 World War I fighter pilot movie, was the first production to win the Academy Award for Best Picture. To capture realistic point of view shots of the actors engaged in aerial dog fights, the two leads Charles “Buddy” Rogers and Richard Arlen actually piloted their own bi-planes, with motorized cameras affixed to the cockpit recording their faces and the action and swooping landscapes behind them. The movie’s thrilling aerial cinematography will never be surpassed because it was all staged for real. Most of the movie was filmed on location at Kelly Field in San Antonio, Texas.

Wings, a 1927 World War I fighter pilot movie, was the first production to win the Academy Award for Best Picture. To capture realistic point of view shots of the actors engaged in aerial dog fights, the two leads Charles “Buddy” Rogers and Richard Arlen actually piloted their own bi-planes, with motorized cameras affixed to the cockpit recording their faces and the action and swooping landscapes behind them. The movie’s thrilling aerial cinematography will never be surpassed because it was all staged for real. Most of the movie was filmed on location at Kelly Field in San Antonio, Texas.

Buddy Rogers returns home … to Glendale

Continuing with posts concerning Southern Pacific depots appearing in silent film (see HERE and HERE), a concluding scene from Wings was filmed at the SP depot in Glendale, now called the Glendale Amtrak train station, the same station Buster Keaton used the same year when filming his campus comedy College (1927) and also appearing in the film noir classic Act of Violence (1948) (see both below). Towards the end of Wings Buddy Rogers’s character returns home from the war, and receives a hero’s welcome at his local train station. Although very little of the station appears on camera, several clues confirm the site. Since Buddy’s white picket-fence home-town was implied to be set in “middle America” (i.e., not in Southern California), I have to infer that the elaborate Spanish baroque-style building was deliberately kept off camera to avoid breaking the illusion.

The celebratory procession shows the Glendale station sign (oval) and window (box). Photo courtesy Atwater Village Newbie.

Click to enlarge and compare the signs – you can see the letter “G” outlined in white in both images. They attempted to cover up the Glendale sign with a “welcome ” sign when filming. USC Digital Archive.

Click to enlarge – a closer view of the matching windows

The remainder of this post is a re-post of Buster Keaton’s brush with film noir (see Harold Lloyd’s prior noir posts HERE, HERE, and HERE, and Charlie Chaplin’s noir post HERE), when filming College at the back, rather than the front of, the same Glendale station appearing in Wings.

Buster Keaton in College (1927) to the left, and Van Heflin in Act of Violence (1948) right.

The station is now the Glendale Amtrak Station.

The Glendale Southern Pacific station was barely three years old when Buster Keaton used it to portray the station for Clayton, the fictitious college town where Buster’s character pursues higher learning in the 1927 comedy College. Above to the right, the station was also the setting for the climax to Act of Violence, a 1948 noir drama starring Van Heflin and Robert Ryan, who portray re-united army veterans who were once imprisoned together in a German POW camp during WWII. Act of Violence contains several scenes filmed on Court Hill, near the Hill Street Tunnel, and on Bunker Hill, near Angel’s Flight. Unfortunately, these nighttime scenes are darkly lit, and tightly framed, so there is not much to see.

Matching views looking north. Glendale is re-named Santa Lisa for the Act of Violence shot. California History Room, California State Library, Sacramento, California.

Act of Violence does contain a nice view of Clay Street, the narrow alley running between and parallel to Hill Street and Olive Street, and underneath the mid-way point of the Angel’s Flight elevated tracks. As shown below, Harold Lloyd filmed a runaway bus stunt on Clay Street for his 1926 comedy feature For Heaven’s Sake.

Earlier during Act of Violence, Van Heflin runs south down Clay Street towards Angles Flight. The same Clay Street setting appears during the wild double-decker bus chase in Harold Lloyd’s 1926 comedy For Heaven’s Sake, above left. The same area of Clay Street is marked with a yellow box in each image.

Harold Lloyd filmed many other movies on Bunker Hill, and I will explore more Lloyd/noir connections in further posts.

As Lindsay Blake proves in her wonderful I’m Not a Stalker film and TV location blog, the noir classic Double Indemnity (1944), starring Barbara Stanwyck and Fred MacMurray was NOT filmed at the Glendale station, but actually the Burbank station, even though a “GLENDALE” sign appears during the scenes in the movie. Instead, for some reason they put a “GLENDALE” sign on the Burbank station for the shot. You can read about this and several other movies filmed at the Glendale station in Lindsay’s post HERE.

Wings Paramount Home Entertainment.

College frame images reproduced courtesy of The Douris Corporation, David Shepard, Film Preservation Associates, and Kino International Corporation.

HAROLD LLOYD images and the names of Mr. Lloyd’s films are all trademarks and/or service marks of Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc. Images and movie frame images reproduced courtesy of The Harold Lloyd Trust and Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc.

Act of Violence copyright 1948 Loew’s Incorporated.

View Larger Map

Filed under: Buster Keaton, College, Film Noir Tagged: Act of Violence, angles flight, Buddy Rogers, bunker hill, Buster Keaton, film noir, film noir locations, Harold Lloyd, Los Angeles Historic Core, Richard Arlen, Silent Comedies, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, Southern Pacific Depot, SP Depot, Wings

January 14, 2013

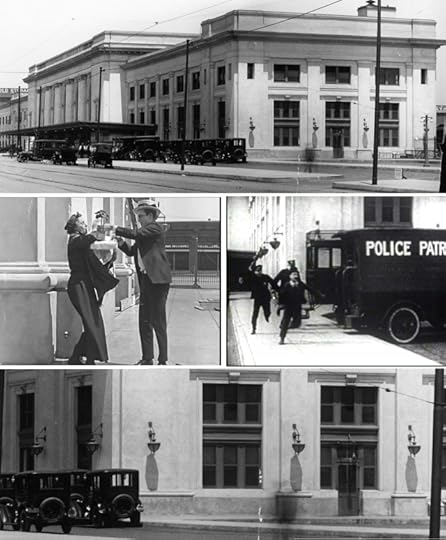

Silent Cameos of the lost Southern Pacific Depot

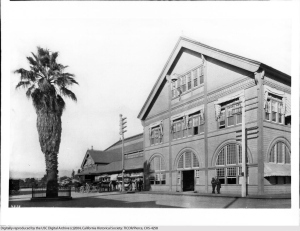

The former Southern Pacific Depot at 5th and Central (in service from 1915 to 1939) – USC Digital Archive

Before the beautiful downtown Los Angeles Union Train Station opened in 1939, built on the site of the original Chinatown, the various railroads serving L.A. each operated from their own stations. Union Station helped to reduce downtown noise and congestion by consolidating the Union Pacific, Santa Fe, and Southern Pacific city entrances and stations into a single terminal. As with so many other Los Angeles landmarks now lost to the wrecking ball, glimpses of the former Southern Pacific Depot, that once stood at E. 5th Street and Central Avenue (pictured above), are unwittingly preserved in the background of numerous silent comedies.

Douglas Fairbanks at the Southern Pacific Depot – When the Clouds Roll By

One early appearance comes during a stunt from the Douglas Fairbanks comedy When the Clouds Roll By (1919), as Doug scampers up the Southern Pacific Depot’s front awning (above).

The former Arcade Depot (1889 – 1914) USC Digital Archive

The Southern Pacific Depot opened to great fanfare on June 12, 1915. Built at a cost of $750,000 on the site of the former Arcade Depot (1889 – 1914), the Southern Pacific Depot was touted as the nation’s finest building of its kind west of Kansas City. The station was 572 feet long, with a concourse 280 feet long, by 80 feet wide and 50 feet high. Ten passenger tracks, protected by four concrete umbrella sheds each 780 feet long, were accessed by subways so that passengers no longer needed to cross tracks to reach their particular trains.

Two now lost stations – the extant Union Station, that replaced the SP and Santa Fe Depots, stands several blocks further north on this map.

The Southern Pacific Depot played a key role in Harold Lloyd’s 1924 feature comedy Girl Shy. As I explain in my book Silent Visions, Harold and lead actress Jobyna Ralston are filmed arriving in town at the Santa Fe Depot on Santa Fe Avenue near 1st Street. Yet they say their good-byes to one another in front of the Southern Pacific Depot, several blocks to the west, as shown on this vintage map (left).

As I may discuss in a later post, the Santa Fe Depot was a popular place to film, appearing in numerous Hal Roach Studios productions including Charley Chase’s Crazy Like A Fox (1926), Laurel & Hardy’s Berth Marks (1929), the Our Gang comedy Choo-Choo! (1932), and in Lloyd’s independently produced taking picture Movie Crazy (1932).

Below, Harold Lloyd at left, in front of the Southern Pacific Depot in Girl Shy, and Stan Laurel playing a hansom cab driver in his pre-Oliver Hardy solo comedy Mother’s Joy (1923).

Harold Lloyd and Stan Laurel both in front of the Southern Pacific Depot.

Filmmakers not only captured the western (front) side of the Southern Pacific Depot, the south end of the station (the side facing the sun all day) also appears in vintage comedies. In Just Neighbors (1919) (see left below) Harold Lloyd races around the station corner attempting to catch the next train home, when he runs into several people blocking his way. In Be Reasonable (1921), Billy Bevan (see right below) flees the police by racing south from the station during a lengthy chase, presaging Buster Keaton’s similar chase in Cops (1922). Notice the former station’s distinctive light fixtures along the corner walls.

Left – Harold Lloyd in Just Neighbors; right – Billy Bevan in Be Reasonable. USC Digital Archive

Harold Lloyd’s short film Just Neighbors also provides some remarkably rare views of the interior of the lost station. Compare this photo below, with scenes from Harold’s movie.

A rare interior view of the Southern Pacific Depot – USC Digital Archive. Note: the archive credits this photo as around 1956, perhaps a typo for the more likely 1936.

Click to enlarge. Harold’s ticket counter appears left center.

Below, the extant Rosslyn Hotel (1913) at 5th and Main appears in the background during a scene from Girl Shy as Harold runs west after Jobyna’s taxi cab down 5th Street from the Southern Pacific Depot. In the matching modern view, the US Bank Tower, the tallest building on the West Coast, dominates the skyline. At 1,018 feet, the building stands nearly seven times as tall as the 150-foot height limit imposed in Los Angeles for many decades. I don’t think anyone involved with filming Harold’s scene could have imagined that the downtown skyline would someday appear this way.

Click to enlarge. Harold runs down 5th Street from the Southern Pacific Depot – a matching modern view.

Below, the cold storage distribution facility, standing on the site of the Southern Pacific Depot today, was completed in May 1958.

View Larger Map

When the Clouds Roll By (1919)—Douglas Fairbanks: A Modern Musketeer Collection (David Shepard, Film Preservation Associates, Jeffrey Masino, Flicker Alley LLC).

HAROLD LLOYD images and the names of Mr. Lloyd’s films are all trademarks and/or service marks of Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc. Images and movie frame images reproduced courtesy of The Harold Lloyd Trust and Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc.

Mother’s Joy (1923)—The Stan Laurel Collection Slapstick Symposium (Eric Lange and Serge Bromberg, Lobster Films).

Be Reasonable (1921)—American Slapstick 2 Collection (All Day Entertainment, David Kalat).

Filed under: Girl Shy, Hal Roach Studios, Harold Lloyd, Los Angeles Historic Core, Stan Laurel Tagged: Arcade Depot, Harold Lloyd, Los Angeles Arcade Depot, Los Angeles Historic Core, Los Angeles Southern Pacific Depot, Los Angeles Train Stations, Los Angeles Union Station, Santa Fe Depot, Silent Comedians, Silent Comedies, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, Southern Pacific Central Depot, Stan Laurel, then and now

December 26, 2012

Front and Back Cameos – 100 years of a Hollywood landmark

In Why Worry? above, Harold Lloyd’s friend the giant celebrates news of Harold becoming a father.

Toberman Hall has stood at 6410-6414 Hollywood Boulevard (each oval above) since 1907. Its original two-story neighbor to the left, at the southwest corner of Cahuenga and Hollywood Boulevard (pictured in the black & white images above) was replaced with a four-story building around 1926 (see color image above). As shown, Toberman Hall witnessed the antics of Marie Dressler and a young Charlie Chaplin in the first Hollywood-produced feature length comedy Tillie’s Punctured Romance (1914), and a decade later appeared in Harold Lloyd’s 1923 feature Why Worry?

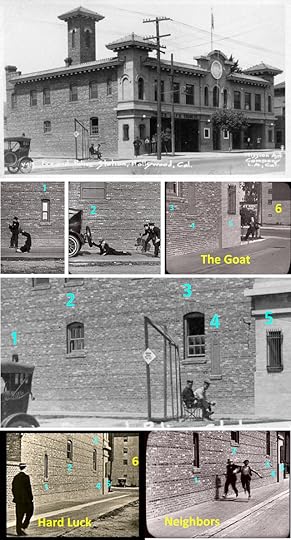

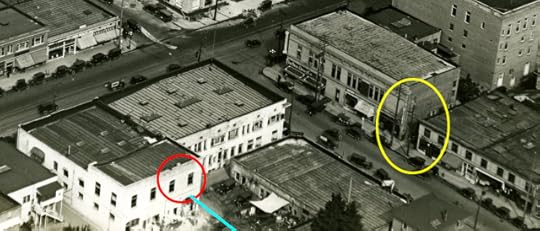

As shown, the back of Toberman Hall (red oval below) appears in Buster Keaton’s 1921 short comedy The Goat, where Buster filmed a scene in the alley alongside the former fire/police station facing Cahuenga.

During the above scene from The Goat, Buster lands face down in an alley after being dragged into view by a speeding car, barely visible at the left. Behind him is a low brick wall and the south side of the joint Hollywood Fire and Police Station that stood at 1625 and 1629 Cahuenga Boulevard. The red ovals above identify matching windows of the back of Toberman Hall, and the point of view (blue line) from the fire station alley. The aerial view above shows that this alley originally had no building along the other side.

A modern office building now stands along the extant fire station alley. (C) 2012 Google.

This modern aerial view above shows the back of the extant Toberman Hall, aligned with the extant fire station alley, with the fire/police station replaced by a modern office building.

How do I know Keaton filmed this scene in the fire station alley, showing the back of Toberman Hall, especially since the station was destroyed by fire in December 1979? Hollywood author and historian Tommy Dangcil (Hollywood 1900-1950 in Vintage Postcards, and Hollywood Studios) provided me with this post card that links the clues all together.

The unique fire station alley windows (1-5) and the Go West parking lot (6) across the street. Photo Tommy Dangcil.

Buster at the fire/police station in Three Ages

The Hollywood Fire and Police Station (see full view above) stood at 1625-1629 Cahuenga Boulevard. As I discuss in my books Silent Echoes and Silent Visions, the station appeared in Buster Keaton’s feature films Three Ages (1923) (see left) and The Cameraman (1928), as well as in Harold Lloyd’s Safety Last! (1923) and Hot Water (1924). What’s more, we can see from the unique window configuration (1-5 above) that Keaton used the fire station alley for three different films, The Goat, Hard Luck (1921), and Neighbors (1920).

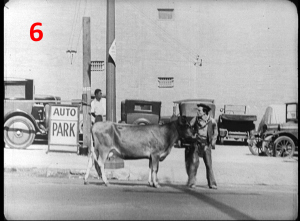

(6) Buster and Brown Eyes in Go West, across the street from the fire/police station.

During scenes from The Goat Buster runs past the corner of the fire station (above right) and hides under a car parked in the fire station alley. When the car drives off, revealing Buster to the police, he grabs the bumper for a quick getaway (above center), only to land on his face moments later (above left). These three shots reveal the five unique fire station windows (1-5) identified above. The above scene from Hard Luck shows Keaton before hitching a ride on the back of a passing car, revealing the entire length of the fire station alley (this shot appears only on the Keaton Plus DVD version of the film), while the above scene from Neighbors shows a policeman harassing a man he mistakenly thinks is Buster. Last, the views in The Goat and Hard Luck down the fire station alley reveal the small parking lot across the street (6) where Buster left his pet cow Brown Eyes during his 1925 feature Go West (inset).

Plenty of room and sun to film.

Why did Keaton film at this alley so frequently? As shown in this 1922 vintage aerial view (left), the fire station alley originally had no building along its south flank, exposing the length of the alley to the sun nearly all day long, and providing unobstructed room to place cameras and equipment. Moreover, the alley was situated off of the same block of Cahuenga where Keaton filmed many other scenes, and was close to the Keaton Studio just a few blocks to the south.

To see many more amazing photos of this old fire station, visit the Photo Gallery at the Los Angeles Fire Department Historical Archive, and open the photos for Fire Station 27. Then, mid-way down the page click the 1913-1930 link (the years this station was in service) to see many exterior and interior historic photos.

This final view shows the back of Toberman Hall (red oval) relative to the alley (yellow oval) where Keaton grabbed a passing car one-handed in Cops (1922) (see post HERE).

Another 1922 view of Toberman Hall (red oval) in relation to the Cops alley (yellow oval).

Historic aerial photos from Bruce Torrence, at HollywoodPhotographs.com.

Tillie’s Punctured Romance Copyright 2010 by Lobster Films for the Chaplin at Keystone Project, from Flicker Alley. All images from Chaplin films made from 1918 onwards, copyright © Roy Export Company Establishment. CHARLES CHAPLIN, CHAPLIN, and the LITTLE TRAMP, photographs from and the names of Mr. Chaplin’s films are trademarks and/or service marks of Bubbles Incorporated SA and/or Roy Export Company Establishment. Used with permission.

The Goat, Three Ages, and Go West are licensed by Douris UK, Ltd., and are all available on Blu-ray from Kino Lorber.

HAROLD LLOYD images and the names of Mr. Lloyd’s films are all trademarks and/or service marks of Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc. Images and movie frame images reproduced courtesy of The Harold Lloyd Trust and Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc.

Below, the fire station alley to the left, and the back of Toberman Hall to the right.

View Larger Map

Filed under: Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, Hollywood Tour Tagged: Buster Keaton, Chaplin Locations, Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, Hollywood Tour, Keaton Locations, Lloyd Locations, Silent Comedians, Silent Comedies, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, then and now

December 15, 2012

Keaton’s Short Fuse – Cops, Musso & Frank, and enduring Hollywood history

What do I do with this now? Buster blithely lights a cigarette in Cops.

Buster on parade, filmed in 1922 at the Goldwyn Studio in Culver City, prior to the creation of M-G-M in 1924.

At one point during Buster Keaton’s most famous short film Cops (1922), Buster finds himself and his newly acquired horse-cart full of furniture in the middle of the annual Policeman’s Day Parade. After politely tipping his hat in recognition to the parade-route crowds, Buster pulls out a cigarette and fumbles for a light. At that moment, an anarchist (an overused silent comedy trope, but grounded in real-life tragedies such as the 1920 Wall Street bombing and 1910 Los Angeles Times Building bombing) tosses a bomb from a rooftop that lands conveniently on Buster’s bench. While other comedians at the time might have mugged hysterically reacting to this predicament, Buster blithely notices the sputtering fuse, puts the flame to good use to light his cigarette, and then serenely ponders how to dispose of the no-longer-useful object. The brief scene is one Keaton’s most iconic, a three-second long vignette of Buster’s unique persona.

As revealed in this story, the amazing detail in the new Kino Lorber Blu-ray release of Keaton’s films allows us to solve where this rooftop scene was filmed, and discover its amazing connection to two venerable Hollywood institutions; the legendary eatery Musso & Frank, and Grauman’s Egyptian Theater, today home to The American Cinematheque.

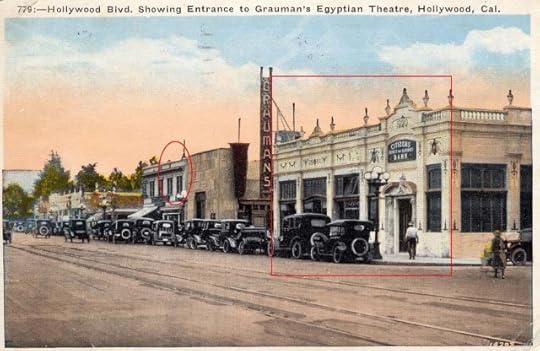

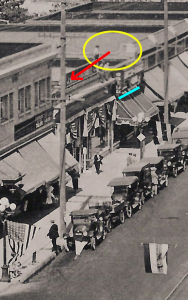

Looking west – the bomber atop 6667 Hollywood Blvd., current site of the Musso & Frank Grill – the original grill site at 6669 stands next door out of view. The oval and box (match below) flank the Egyptian Theater under construction.

Looking east – the oval and box flanking the theater match those above. Courtesy Tommy Dangcil

It turns out the anarchist was standing on the rooftop of 6667 Hollywood Boulevard, the modern day home to the Musso & Frank Grill restaurant, founded in 1919. But at the time of filming (in 1922), the original (and shorter) Musso & Frank building (at 6669), stood immediately next door to the west, just below view behind the bomber. I solved this puzzle by reckoning from the Hollywood Fireproof Storage Building visible in the background of the movie frame. It still stands today, reconfigured in 1935 as the Max Factor Building on Highland Avenue, and now home to the Hollywood Museum. The arrows at left, and below, all point west down Hollywood Boulevard from the rooftop corner where the bomber stood (yellow oval). The blue line at left underscores the grill sign.

It turns out the anarchist was standing on the rooftop of 6667 Hollywood Boulevard, the modern day home to the Musso & Frank Grill restaurant, founded in 1919. But at the time of filming (in 1922), the original (and shorter) Musso & Frank building (at 6669), stood immediately next door to the west, just below view behind the bomber. I solved this puzzle by reckoning from the Hollywood Fireproof Storage Building visible in the background of the movie frame. It still stands today, reconfigured in 1935 as the Max Factor Building on Highland Avenue, and now home to the Hollywood Museum. The arrows at left, and below, all point west down Hollywood Boulevard from the rooftop corner where the bomber stood (yellow oval). The blue line at left underscores the grill sign.

The original Musso & Frank Grill, at 6669 Hollywood Blvd. courtesy HollywoodPhotographs.com. The oval marks the west edge of 6667 Hollywood Blvd., the current home to Musso & Frank. The arrow points west in both images.

This circa 1928 view looks east – the palm trees in front of the Hotel Hollywood stand at the lower left corner of Hollywood and Highland. Los Angeles Public Library.

Below, a final overview aligning the rooftop bomber and the Hollywood Storage building.

Hollywood Then (1926) and Now. (A) marks the Hotel Hollywood, now (B) the Hollywood and Highland entertainment center (there are red carpets in the street for the Oscar ceremonies), (C) the First National Bank tower (completed in 1928), (D) the Hollywood Fireproof Storage building, now the Hollywood Museum, (E) the Montmartre restaurant building, (F) the Hotel Christie (opened in 1923), (G) the south end of the Egyptian Theater forecourt (opened in 1922), (H) 6669 Hollywood Blvd. (the original Musso & Frank site), and (I) 6667 Hollywood Blvd., the current Musson & Frank site. b&w image HollywoodPhotgraphs.com – color image (C) 2012 Google.

There is more to this story. George Wead’s bibliography of Keaton reports that Buster filmed Cops between December 1921 and January 1922 (thanks David B. Pearson). Though a bit difficult to discern, the rooftop bomber shot also provides an early view of the Egyptian Theater site, taken ten months or so before the theater opened. The Los Angeles Times reported, following a May 7, 1921 dedication ceremony, that construction of Sid Grauman’s so-called Hollywood Theater was planned to start May 9, 1921, and that with rushed construction it was anticipated to open by November 1921. A later November 4, 1921 story said that barring unforeseen circumstances the theater would likely open by February 1922. Yet the theater did not open until October 18, 1922, with the premiere of Douglas Fairbanks’s epic adventure Robin Hood.

Close-up view of Egyptian Theater construction site. I believe the triangle (right red arrow) is a street car traffic sign, suspended from a wire across the street. The bottom arrow points across what appears to be the top edge of billboards pasted on a construction site fence fronting the sidewalk. The mystery is the left arrow, pointing down toward a pitched face building that appears to have Gothic-arched windows. A squat, block-shaped Egyptian-style structure (blue arrow) was later built at this spot.

The theater is known for its large forecourt fronting Hollywood Boulevard, framed to the east by a long narrow commercial building forming one side of the court leading to the theater doors (see below). It appears from the frame above that at one time the face of this commercial wing had a different style than the squat block-shaped face that was later built.

Above, the original Egyptian Theater forecourt. The Dunn’s Men’s Shop, to the right of the forecourt (yellow oval), appears in Harold Lloyd’s 1921 short comedy Never Weaken. The store was replaced by the Pig ‘N Whistle restaurant in 1927.

Harold also filmed at the corner of Hollywood Blvd. and McCadden Place, as shown.

Cops is licensed by Douris UK, Ltd., and available as part to the Kino Lorber Buster Keaton: The Short Film Collection (1920-1923).

HAROLD LLOYD images and the names of Mr. Lloyd’s films are all trademarks and/or service marks of Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc. Images and movie frame images reproduced courtesy of The Harold Lloyd Trust and Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc.

View Larger Map

Filed under: Buster Keaton, Cops Tagged: American Cinematheque, Buster Keaton, Cops, Egyptian Theater, Grauman's Egyptian Theater, Hollywood Boulevard, Hollywood History, Hollywood Tour, Keaton Locations, Musso & Frank, Silent Comedians, Silent Comedies, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, then and now

October 14, 2012

Harold Lloyd – Film Noir – Criss Cross and the Hill Street Tunnel

Burt Lancaster in Criss Cross along the north end of the Hill Street Tunnel. The box marks where Lloyd filmed.

A set for The Terror Trail (1921) overlooking the south end of the Hill Street Tunnel – Marc Wanamaker Bison Archives

Harold Lloyd, Buster Keaton, and many other silent comedians filmed stunt comedy sequences by building sets on Court Hill overlooking the south end of the former Hill Street Tunnel. As shown at left, filming a set against the street far below, while cropping the tunnel balustrade from view, created the illusion of great height. This remarkable setting was also adjacent to the magnificent Bradbury Mansion, one of the city’s finest original homes, that was later used as an early movie studio by Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, and Hal Roach, and was close to Court Flight, the city’s second (and now lost) funicular railway. You can see more pictures of the Bradbury Mansion, Court Flight, and the south end of the Hill Street Tunnel, in this earlier post (HERE), and can read all about them in my three books. (Note: this is my sixth post so far connecting silent comedy and film noir – there will be many more, especially regarding Harold Lloyd. You can link to these other noir posts HERE).

Burt Lancaster in Criss Cross at the north end of the Hill Street Tunnel. The top of this blog shows him walking by the back railing toward 215 N. Hill Street, the big white house in the back, discussed later.

Lizzies of the Field

While the south end of the Hill Street Tunnel appears in dozens of silent comedies, the first film appearance of the north end of the Hill Street Tunnel of which I am aware is in the Burt Lancaster film noir drama Criss Cross (1949), co-starring a young and lovely Yvonne De Carlo as the femme fatale, who would later play matriarch Lilly Munster in the 1960s sitcom The Munsters.* In the above frame, Burt returns to Los Angeles by exiting a trolley at the north end of the Hill Street Tunnel at the corner of Temple. As shown at the end of this post on Google Street View, this corner, now part of the Los Angeles Civic Center, is redeveloped beyond recognition. The homes, the tunnel, and even the hill have all been graded flat. (*I realize now that during the Mack Sennett comedy Lizzies of the Field (1924) there is a brief shot approaching the north end of the tunnel – see inset).

Court Hill – the north end of the Hill Street Tunnel (right) relative to the Bradbury Mansion and Court Flight. Map by Piet Schreuders

A view from City Hall comparable to the map above – the arrow shows Burt’s path as shown at the top of this post. The box is enlarged below. The oval marks Yvonne’s car, discussed later.

Harold Lloyd in Take A Chance before the Majestic Apartments at 406 W Temple – steps from the north end of the Hill Street Tunnel.

As explained here, and in future posts, Harold Lloyd frequently filmed scenes from his early short comedies within steps of the former Bradbury Mansion studio on Court Hill, providing rare glimpses of this long-lost Los Angeles neighborhood that was later excavated and graded flat. Take A Chance (1918, shown above), was filmed at 406 Temple near the north end of the Hill Street Tunnel, just steps from where Burt Lancaster exited the trolley in Criss Cross. Down to his last dime, when Harold exits the Majestic Apartments situated directly between a barber shop and a restaurant, he flips the coin to decide whether to eat, or to spruce himself up, only to lose the dime in a storm drain.

As explained here, and in future posts, Harold Lloyd frequently filmed scenes from his early short comedies within steps of the former Bradbury Mansion studio on Court Hill, providing rare glimpses of this long-lost Los Angeles neighborhood that was later excavated and graded flat. Take A Chance (1918, shown above), was filmed at 406 Temple near the north end of the Hill Street Tunnel, just steps from where Burt Lancaster exited the trolley in Criss Cross. Down to his last dime, when Harold exits the Majestic Apartments situated directly between a barber shop and a restaurant, he flips the coin to decide whether to eat, or to spruce himself up, only to lose the dime in a storm drain.

The right arrow points to Harold – the left arrow follows Burt towards the big white house 215 Hill St (yellow oval).

The prominent white house at 215 N. Hill Street portrayed Burt’s family home in Criss Cross. This view below shows that this home (yellow box) and the Majestic Apartments (red box) were two of the last structures standing before Court Hill was excavated.

Burt filmed at 215 Hill St (yellow box), Harold at the Majestic on Temple (red box) – Los Angeles Public Library

At left, Burt climbs the long flight of steps from the sidewalk up to his family’s home front porch at 215 N. Hill Street. Later, when Burt traverses back down the steps to the sidewalk (below), in a reverse view you can seen the flat terrace that stood above the north end of the Hill Street Tunnel, and details of some Civic Center buildings in the background.

At left, Burt climbs the long flight of steps from the sidewalk up to his family’s home front porch at 215 N. Hill Street. Later, when Burt traverses back down the steps to the sidewalk (below), in a reverse view you can seen the flat terrace that stood above the north end of the Hill Street Tunnel, and details of some Civic Center buildings in the background.

Looking south towards the terrace above the north end of the Hill Street Tunnel. The red box marks the extant Hall of Justice, completed in 1925. The building to the left of the red box in the movie frame was the former Alhambra Hotel. It originally stood on the corner of Temple and Broadway, and was moved laterally further north up Broadway to clear the site for the Hall of Justice on the corner. The Alhambra stood for years beside the south face of the Broadway Tunnel, another Los Angeles landmark lost to history. The yellow box marks the same corner of the United States District Court House. (C) 2012 Microsoft Corporation – Pictometry Bird’s Eye (C) 2012 Pictometry International Corp.

This aerial below shows the line of sight from the front porch of 215 N. Hill Street towards the corner of the Hall of Justice at the corner of Temple and Broadway.

USC Digital Archive

Criss Cross also has scenes filmed near Angles Flight, and Clay Street, the alley running underneath the Angles Flight elevated tracks, that appear during sequences in Harold Lloyd’s feature comedy For Heaven’s Sake (1926), but I’ll save these comparisons for another day.

The future Mrs. Lilly Munster beside a very Munsteresque house

In closing, here above is a view of Yvonne De Carlo waiting in a convertible parked on Hill Street along the south face of 401 Court Street, the large home on the corner of Hill and Court Street that once stood across from the Bradbury Mansion. The Bradbury was demolished in 1929, but its neighbor, pictured here, held on until at least the 1948 filming of Criss Cross, but did not survive long enough to appear in the 1951 Sanborn Fire Insurance maps. The relative position of Yvonne’s car is marked with an oval on the map and aerial views above.

My book Silent Visions has an entire chapter devoted to Harold Lloyd filming on Bunker Hill. Look for future posts of Harold filming at noir classic settings.

HAROLD LLOYD images and the names of Mr. Lloyd’s films are all trademarks and/or service marks of Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc. Images and movie frame images reproduced courtesy of The Harold Lloyd Trust and Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc.

Criss Cross (C) 1948 Universal Pictures Company, Inc.

This Google Street View of the corner of Hill and Temple matches the large movie frame of Burt Lancaster exiting the trolley above. Today the Bradbury Mansion, the Hill Street Tunnel, Court Flight, and Court Hill itself, are just memories.

View Larger Map

Filed under: Bunker Hill, Film Noir, Harold Lloyd, Los Angeles Historic Core Tagged: bunker hill, Criss Cross, film noir, film noir locations, Harold Lloyd, Los Angeles Historic Core, noir, Silent Comedians, Silent Comedies, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, then and now

October 6, 2012

Buster and the Three Stooges at the Columbia Ranch – Part 3

Buster in General Nuisance – looking south down Kenwood Street from Oak towards the Warner Bros. Studio in the far distance, nestled at the foot of Mt. Lee and Cahuenga Peak.

(C) 2012 Google

As discussed in prior posts, Buster Keaton and the Three Stooges nearly crossed paths in Cops (1922) and Soup To Nuts (1930) (see HERE), and did cross paths in Neighbors (1920) and Soup To Nuts (see HERE), before filming their respective Columbia short subjects General Nuisance (1941) and Boobs in Arms (1940) on the same back lot called the Columbia Ranch located in Burbank at the corner of Oak Street and Hollywood Way (see Part 1 HERE and Part 2 HERE). Concluding this series, we’ll look at where Buster filmed scenes on Kenwood Street just south of the Columbia Ranch, known today as the Warner Brothers Ranch.

In General Nuisance Buster portrays an effete millionaire who enlists in the army to impress a woman who prefers a man in uniform. Buster’s scenes were filmed along Oak Street and Kenwood Street, adjacent to the Columbia Ranch.

Click to enlarge. Left to right – three extant homes, 330, 324, and 320 Kenwood – the arrow marks the Warner Bros. Studio water tower. 330 Kenwood also appears below.

330 Kenwood appears behind Buster.

Above, Buster hitches a ride south down Kenwood with some diplomats after his car breaks down. The three extant homes visible above were then the only homes on the block. The prominently exposed front home (330) now has a towering pine tree on its once bare lawn. Earlier, Buster meets two women parked along Oak Street (left), as the same home at 330 Kenwood appears in the background. The detached garage for 330 Kenwood (open door at left) has been replaced with a two-story mother-in-law unit.

Each oval marks the west side of the same Columbia Ranch bungalow – Buster’s view looks east down Oak.

East down Oak today

Above right, Buster’s car breaks down on Oak Street, looking east along the south border of the Columbia Ranch. In the back you can see a pair of twin bungalows on the studio property that appear prominently later in Buster’s film and, as explained in my prior posts, during the Stooges’ Boobs In Arms, appearing above left. The western-most of the two bungalows, marked with an oval above, was replaced by a large structure, but its twin to the east remains standing near the Oak/Hollywood Way corner entrance to the Warner Brothers Ranch.

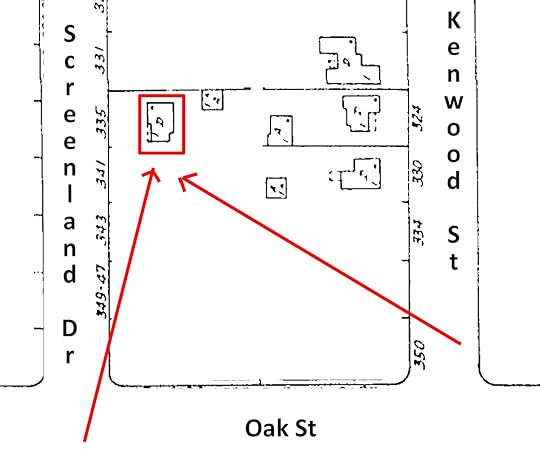

Two views of the north side (box) of 335 Screenland Drive, now lost.

You can get a sense of how bare suburban development was here in the early 1940s by comparing these images above from the two movies. Each image shows the north face of the bungalow that once stood at 335 Screenland Drive – at the time the only home on the block. Today large apartment blocks squat along both sides of Screenland Drive. The map at the left looks south, and shows the point of view from the Stooges’ movie (left arrow) and from Buster’s movie (right arrow) towards the home at 335 Screenland. Only four homes (and three detached garages) stood on the bare land south of the Columbia Ranch during the time of filming.

You can get a sense of how bare suburban development was here in the early 1940s by comparing these images above from the two movies. Each image shows the north face of the bungalow that once stood at 335 Screenland Drive – at the time the only home on the block. Today large apartment blocks squat along both sides of Screenland Drive. The map at the left looks south, and shows the point of view from the Stooges’ movie (left arrow) and from Buster’s movie (right arrow) towards the home at 335 Screenland. Only four homes (and three detached garages) stood on the bare land south of the Columbia Ranch during the time of filming.

During the Stooges’ drill practice scene from Boobs In Arms, shown above, you can also look south from the studio and see the north face of the extant bungalow at 224 Kenwood, marked with a yellow box. To the right of the yellow box in the Stooges frame is the north side of 330 Kenwood, the home discussed above. The matching modern aerial view, shown above, looks south from what is now the Warner Brothers Ranch toward 224 Kenwood. The red oval above marks the surviving of the twin bungalows mentioned previously. I explain other features visible in this aerial view in my prior posts.

For information on the Columbia Ranch, I highly recommend the unofficial ranch website here.

The Mike McDaniel and Wes Clark Burbank history website Burbankia can be found here.

Movie frame images copyright Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. Aerial view (C) 2012 Microsoft Corporation – Pictometry Bird’s Eye (C) 2012 Pictometry International Corp.

View Larger Map

Filed under: Buster Keaton, Columbia, Three Stooges Tagged: Boobs In Arms, Buster Keaton, Columbia Movie Ranch, Columbia Studios, General Nuisance, Silent Comedians, Silent Comedies, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, Three Stooges, Warner Bros., Warner Ranch

September 25, 2012

Harold Lloyd – By the Sad, Santa Monica Waves

Click to enlarge. The Santa Monica Pier, circa 1917. The carousel was built in 1916, the bowling and billiard parlor to the right opened in 1917, along with the Blue Streak Racer roller coaster, a dual track racing coaster, at back - Department of Special Collections, University of Southern California.

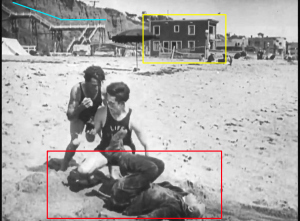

Harold in full David Hasselhoff mode at the same beach where the Baywatch TV show was later filmed.

During Harold Lloyd’s 1917 short film, By The Sad Sea Waves, Harold pretends to be a beach life guard in order to impress the ladies. Filmed where David Hasselhoff would film Baywatch many decades later, By The Sad Sea Waves provides a wonderful time capsule view of the Santa Monica pier, and the Looff Carousel and Hippodrome, still in use after nearly 100 years. (The film title is a play on words of “by the glad sea waves,” a somewhat obscure figure of speech at the time.) Built in 1916, the distinctive carousel served as an important location for the 1973 Best Picture The Sting, and is Santa Monica’s first National Historic Landmark.

The Looff Carousel and Hippodrome – Santa Monica’s first National Historic Landmark. The carousel served as an important location for the 1973 Best Picture The Sting. Department of Special Collections, USC – Tony Barraza.

Leisure time and disposable income were in short supply at the turn of the prior century, but as the working class began earning higher wages, and receiving both Saturdays and Sundays off from work, a need arose for local and inexpensive pastimes, and beachfront amusement parks provided welcome entertainment. After saving their nickels, factory workers and office clerks could hop on the trolley and lose themselves for a day at the beach. Many Southern California beach communities had amusement park piers during the silent-film era, and as I explain in great detail in my book Silent Visions, Lloyd filmed at nearly every one of them.

Looking south on the filming site from Palisades Park in Santa Monica – Santa Monica Public Library

Harold attends to a drowning victim – one of many scenes filmed at this spot.

The above photo, taken from Palisades Park overlooking the ocean in Santa Monica, looks south towards the Santa Monica Pier, and shows where most of the scenes from the movie were filmed (left). The blue line marks the stairway and pedestrian bridge leading down from Palisades Park to the beach. Though now rebuilt with cement, the bridge still stands in the same spot, across from the bluff-top terminus of Arizona Avenue. The yellow box marks the former apartment house at 1255 Ocean Front, once the northernmost structure along the cement promenade leading from the pier. You can see the terminus of the promenade in the background of several scenes.

Click to enlarge. Matching views looking south (left) and north (right) at the Palace Bathing Car beach dressing rooms. USC Digital Archive.

Wearing an impromptu disguise, Harold hides from the police beside a Palace Bathing Car beach dressing room, also pictured above and below (yellow boxes).

At the time of filming, most Los Angelenos would arrive at the beach by trolley, wearing suits and ties, and other formal street clothes. They would then rent heavy wool bathing suits from one of the numerous bath houses along the coast, changing either at the bath house, or at small beach dressing rooms available for rent, such as the Palace Bathing Car rooms pictured here, marked by yellow boxes.

A view of the Santa Monica Pier, with the Looff Carousel at the lower right, and the Palace Bathing Car dressing rooms (yellow box) - Security Pacific National Bank Photograph Collection/Los Angeles Public Library.

Below, a view of the Santa Monica Pier today, with the only original structure, the Looff Carousel, at the upper right. Left-click on the photo, and move it around to see the neighboring beach and bluffs.

View Larger Map

The movie concludes as Harold and recent conquest Bebe Daniels ride off into the sunset aboard the Venice Miniature Railway (see below), a popular beachside attraction that once operated about two miles south of Santa Monica. Harold used the same railway to conclude his short comedy Number Please? (1920), only in this film Harold loses the girl, and rides off all alone.

All Aboard!! By The Sad Sea Waves to the left, Number Please? to the right – in the background stands the former Race Thru The Clouds roller coaster that stood beside the former Venice lagoon.

The Venice of America beach resort, pictured below, was built on reclaimed marshland by developer Abbott Kinney starting in 1904. The planned community was situated on eight miles of man-made canals, radiating from a large central lagoon that featured real gondolas and gondoliers imported from Italy, and a two-block business district noted for its covered arched walkways and Venetian Renaissance architecture. Today the lagoon and most of the canals have been paved over, and most of the buildings have been streamlined or demolished. Venice was also home to the former Abbot Kinney amusement pier that appears in several Chaplin, Keaton, and Lloyd comedies.

Kinney installed the Venice Miniature Railway in 1905, as both a tourist attraction and as a means to escort potential home builders and buyers to look at the subdivided parcels he was promoting. The train was very popular for its time, but it interfered with traffic, and was shut down in 1925 when Venice was incorporated into Los Angeles.

Looking west down Windward Avenue towards the ocean. Venice Miniature Railway – Marc Wanamaker – Bison Archives

Below, the same Venice corner at Windward Avenue and Pacific Avenue today. The corner building on the right has had the top floor removed.

View Larger Map

HAROLD LLOYD images and the names of Mr. Lloyd’s films are all trademarks and/or service marks of Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc. Images and movie frame images reproduced courtesy of The Harold Lloyd Trust and Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc.

Filed under: Harold Lloyd Tagged: Abbot Kinney, By The Sad Sea Waves, Harold Lloyd, Looff Carousel, Santa Monica, Santa Monica Carousel, Santa Monica Pier, Silent Comedians, Silent Comedies, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, The Sting, then and now, Venice

September 8, 2012

Buster Keaton – Three Stooges – LAPL Author Lecture

I want to thank everyone for attending my Silent Footsteps lecture held September 15 at the Los Angeles Public Library Taper Auditorium, hosted by Photo Friends.

Using archival photographs, vintage maps, and then and now comparison photos, I led a virtual tour across the lost-and-found neighborhoods of Bunker Hill, Court Hill, and the downtown Los Angeles Historic Core, as documented in the films of Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and Harold Lloyd.

Part of my talk contrasted Buster Keaton’s classic short films Neighbors, The Goat, and Cops with scenes from the very first film appearance of the Three Stooges in Soup To Nuts (1930) (see prior post). I will elaborate on this discovery in a later post, but for now here are Buster and the Stooges, filmed ten years apart in the shadow of City Hall, looking south down Market Street (now lost) from the corner of San Pedro.

Notice the brick work detail on the corner of the building below.

Click to enlarge – looking south down Market Street at San Pedro - Soup To Nuts and Neighbors

Soup To Nuts Copyright 1930 Fox Film Corporation. Neighbors licensed by Douris UK, Ltd. Flyer design – Amy Inouye – Future Studio

Filed under: Buster Keaton, Three Stooges Tagged: Buster Keaton, Keaton Locations, Los Angeles Historic Core, Silent Comedians, Silent Comedies, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, then and now, Three Stooges

August 16, 2012

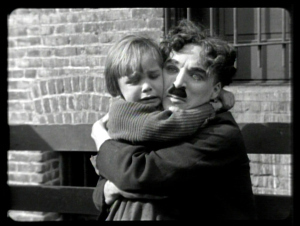

Charlie Chaplin – The Kid’s Tearful Olvera Street Reunion

The heart-tugging reunion in The Kid (1921) played between Charlie Chaplin’s Little Tramp and his “adopted” son (Jackie Coogan) remains one of the most emotionally charged scenes in all of film history. Remarkably, the setting for this iconic scene remains standing, and is passed unknowingly by hundreds of tourists every day. As shown here, the reunion took place on Olvera Street, a colorful Mexican marketplace and cultural center, just north of the Plaza de Los Angeles, that has been a top downtown tourist spot for over 80 years.

The heart-tugging reunion in The Kid (1921) played between Charlie Chaplin’s Little Tramp and his “adopted” son (Jackie Coogan) remains one of the most emotionally charged scenes in all of film history. Remarkably, the setting for this iconic scene remains standing, and is passed unknowingly by hundreds of tourists every day. As shown here, the reunion took place on Olvera Street, a colorful Mexican marketplace and cultural center, just north of the Plaza de Los Angeles, that has been a top downtown tourist spot for over 80 years.

Originally named Wine Street, Olvera Street was renamed in honor of Judge Augustin Olvera, a signatory to the Mexican surrender to the United States in January 1847, and later the first Superior Court Judge of Los Angeles County. The street is home to the oldest building in town, the Avila Adobe, built in 1818, and the Pelanconi House, the oldest brick house in the city, dating from 1855. Olvera Street runs south towards the Plaza de Los Angeles, where Felipe de Neve and a band of settlers founded the city on September 4, 1781. Other city landmarks surround the Plaza, including the Plaza Fire Station, built in 1884, which has appeared both in Buster Keaton’s The Goat (1921) and the contemporary television crime drama Bones.

You can download a PowerPoint presentation about locations from The Kid at this prior post.

Matching views looking south down Olvera Street towards the trees standing in the Plaza de Los Angeles. City Hall, towering in the background, was completed in 1928. The left balcony (to the left of Charlie) is the back of the Sepulveda House (1887), today home to the El Pueblo Visitors Center. The center balcony (appearing above Charlie’s head) is the Pelanconi House. Built around 1855–87, it is the oldest brick building in the city. Today it is home to the La Golondrina Cafe, founded by Consuelo Castilo de Bonzo, which has operated there since the opening of Olvera Street in 1930. Photo courtesy Dr. Lisa Stein Haven.

In 1928, when civic leader Christine Sterling learned that the Avila Adobe was set to be demolished, she rallied a campaign to restore the building, while converting Olvera Street into a Mexican cultural center. Olvera Street opened on Easter Sunday, 1930, and has been a popular tourist destination ever since.

The box marks the fire station appearing in The Goat and in Bones, mentioned above, and the oval marks where Chaplin filmed The Kid. (c) 2012 Microsoft Corporation, Pictometry Bird’s Eye (c) 2012 Pictometry International Corp.

Gerald Smith, Bonnie McCourt, and David Totheroh, the grandson of Chaplin’s cameraman Rollie Totheroh, discovered this location, in part, from clues revealed during a 1964 family interview with the senior Totheroh. As I explain in my book Silent Traces, Chaplin was already familiar with Olvera Street, as he previously filmed chase scenes from Easy Street (1917) along the same spot.

All images from Chaplin films made from 1918 onwards, copyright © Roy Export Company Establishment. CHARLES CHAPLIN, CHAPLIN, and the LITTLE TRAMP, photographs from and the names of Mr. Chaplin’s films are trademarks and/or service marks of Bubbles Incorporated SA and/or Roy Export Company Establishment. Used with permission.

Filed under: Charlie Chaplin, The Kid Tagged: Chaplin film locations, Chaplin Locations, Chaplin Tour, Charlie Chaplin, Jackie Coogan, Olvera Street, Plaza de Los Angeles, Silent Comedians, Silent Comedies, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, The Kid