John Bengtson's Blog, page 22

November 13, 2014

How Charlie Chaplin Filmed The Bank

Click to enlarge each image. Then and now – Charlie Chaplin strolls to work in The Bank beside the Trinity Auditorium.

Charlie Chaplin’s Essanay comedy The Bank (1915) marks his final appearance on camera in downtown Los Angeles. While Broadway, and other nearby Historic Core streets appear in several of his early Keystone films, including Making A Living, His Favorite Pastime, The New Janitor, and especially His Musical Career, discussed in this post, Chaplin would never again stroll these classic urban settings for a movie [note: City Lights (1931) includes scenes of Charlie and the drunken millionaire, likely stunt doubles, driving around downtown]. Film preservationist Serge Bromberg of Lobster Films, the Paris-based company restoring Chaplin’s Essanay comedies, will be screening a restored version of The Bank at the Museum of Modern Art in New York on November 15, 2014, and at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art on November 17, 2014. Ben Model will accompany a further screening of The Bank at MoMA on November 24, 2014.

Click to enlarge. Matching elements of the Trinity Auditorium, 851 S. Grand Avenue. USC Digital Library.

The Bank opens with bank janitor Chaplin strolling to work beside the Trinity Auditorium Building, later known as the Embassy, located at 851 South Grand Avenue near Ninth Street. The first three stories were dedicated to the Trinity Church, while the upper six floors housed a men’s dormitory containing 330 rooms and a rooftop garden capped by a 70-foot diameter dome. The complex featured a library, a gymnasium, tennis and handball courts, a cafeteria, a cafe, and a barbershop. The church’s goal was to satisfy the requirements of mind, body, and soul. “We can take a man from the shower bath to the pearly gates” said Rev. C.C. Selecman when the facility opened.

The auditorium renovation (Photo Hunter Kerhart) – DTLA Rising by Brigham Yen.

The 2,500-seat, three-tier auditorium, with elegant reception halls, and a banquet hall that could seat 1,000, was once the center of Los Angeles culture. The September 21, 1914 opening night concert featured basso opera singer Juan de la Cruz. The Los Angeles Philharmonic, the city’s first permanent symphony orchestra, made its debut here in 1919, playing Dvorzak’s New World Symphony. By the 1930s the hall was known as the Embassy, a celebrated venue for jazz concerts featuring Duke Ellington and Count Basie, while rock concerts played here in the 1960s.

Located in the burgeoning South Park entertainment district, a few blocks from the massive Los Angeles Convention Center and Staples Center complex, the Embassy is being converted into an Empire Hotel.

The Trinity was a popular early filming location. Here it appears behind Harold Lloyd during Bumping Into Broadway (1919).

Jovial inebriates Harold Lloyd and Roy Brooks stagger near The Trinity during High and Dizzy (1919).

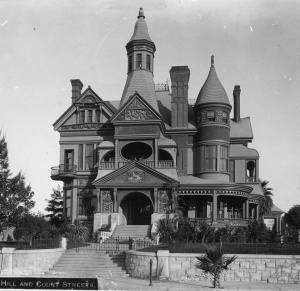

The Bradbury Mansion. USC Digital Library.

Work was Chaplin’s last Essanay project completed at the Bradbury mansion atop Court Hill (see post HERE). In June 1915, Chaplin and company moved to larger quarters at the rented Majestic Studios located at 651 Fairview Avenue in Boyle Heights, where The Bank was filmed on a large open-air shooting stage pictured below.

Chaplin (2nd from left) and crew posing at the Majestic Studio. David Kiehn.

This wonderful shot below shows most of the cast and crew during The Bank‘s production. Notice the muslin light diffusers hanging over the open-air stage. Essanay historian David Kiehn’s book Broncho Billy and the Essanay Film Company identifies nearly every person in this shot. Producer Jesse Robins appears at both ends of this panoramic photo. He accomplished this simply by walking behind the camera from one end of the group to the other during the exposure, as the camera slowly pivoted from left to right.

The arrows identify matching details of the bank set as they appear in the film and in the group photo.

The desk, bank vault, checkerboard floor tiles, and grand staircase evident in the movie frames appear in the right part of the photo.

All images from Chaplin films made from 1918 onwards, copyright © Roy Export Company Establishment. CHARLES CHAPLIN, CHAPLIN, and the LITTLE TRAMP, photographs from and the names of Mr. Chaplin’s films are trademarks and/or service marks of Bubbles Incorporated SA and/or Roy Export Company Establishment. Used with permission. HAROLD LLOYD images and the names of Mr. Lloyd’s films are all trademarks and/or service marks of Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc. Images and movie frame images reproduced courtesy of The Harold Lloyd Trust and Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc.

The Trinity at 851 S. Grand Avenue.

View Larger Map

Filed under: Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, Los Angeles Historic Core Tagged: Bumping Into Broadway, Chaplin Locations, Chaplin Tour, Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, High and Dizzy, Hollywood, Silent Comedians, Silent Comedies, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, The Bank, then and now

November 5, 2014

How Barbara Stanwyck Filmed Night Nurse

Click to enlarge each image posted. Barbara Stanwyck and Ben Lyon watch Clark Gable’s ambulance pass by at the conclusion of Night Nurse. The Dominguez Building tower stands in the far distance.

Directed by William Wellman, Night Nurse (1931) is a classic pre-Code Warner Bros. production, loaded with gratuitous scenes of women undressing, men slapping around women, drunken mothers ignoring their children, women

Directed by William Wellman, Night Nurse (1931) is a classic pre-Code Warner Bros. production, loaded with gratuitous scenes of women undressing, men slapping around women, drunken mothers ignoring their children, women  innocently sharing a bed, and a bootlegger who not only escapes the law but literally gets away with murder to expedite the “happy” ending. Barbara Stanwyck stars as a scrappy nurse with a heart of gold, who is roommates with

innocently sharing a bed, and a bootlegger who not only escapes the law but literally gets away with murder to expedite the “happy” ending. Barbara Stanwyck stars as a scrappy nurse with a heart of gold, who is roommates with  another nurse played by Joan Blondell. Barbara hooks up with a jovial but lethal bootlegger, played by Ben Lyon, to rescue two children from a wealthy, derelict mother, whose chauffeur/lover “Nick,” menacingly played by Clark Gable, plots to kill the children for their trust fund.

another nurse played by Joan Blondell. Barbara hooks up with a jovial but lethal bootlegger, played by Ben Lyon, to rescue two children from a wealthy, derelict mother, whose chauffeur/lover “Nick,” menacingly played by Clark Gable, plots to kill the children for their trust fund.

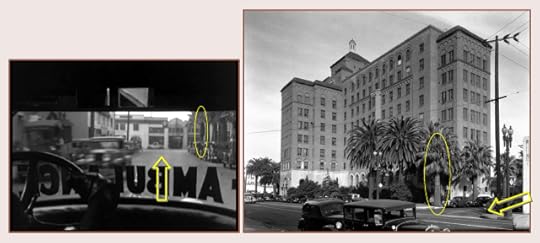

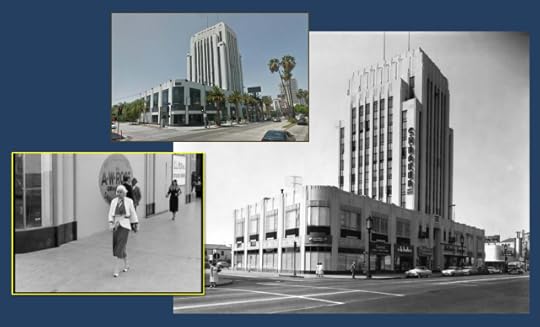

The movie concludes with Barbara and Ben driving west down Wilshire Boulevard from the corner of Dunsmuir (above), the same spot where James Cagney drops off Jean Harlow in Public Enemy (1931) (see below). You can read all about how Harlow and Cagney filmed many Public Enemy scenes along Wilshire Boulevard at this post HERE.

Night Nurse was filmed across from the Wilshire Tower Building, the same spot where James Cagney drops Jean Harlow off in Public Enemy (1931). The Oscar Balzer store (oval) appears in each image. California State Library.

While driving along during the closing scene, Ben explains to Barbara that he told a couple of pals that he didn’t like Clark Gable’s character Nick very much, implying he had Nick taken for a ride. Just then, they stop to watch an ambulance race by, unaware that it is taking Nick’s lifeless body to the morgue.

While driving along during the closing scene, Ben explains to Barbara that he told a couple of pals that he didn’t like Clark Gable’s character Nick very much, implying he had Nick taken for a ride. Just then, they stop to watch an ambulance race by, unaware that it is taking Nick’s lifeless body to the morgue.

As Clark Gable’s ambulance turns east from Burnside onto Wilshire, upper right, we get a clear view west down Wilshire towards the Ralph’s Market building on Hauser. The Pig ‘N Whistle restaurant’s roof top sign (oval) appears during the shot. Jean Harlow and James Cagney drive by the same Pig ‘N Whistle restaurant (see awning sign, oval) in Public Enemy. LAPL.

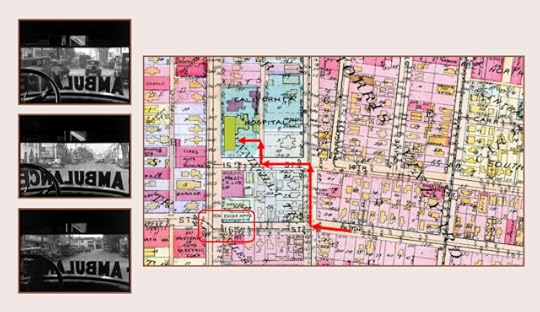

Night Nurse begins with a frantic point of view shot filmed from within an ambulance as it races home, turning wildly right, then left, then right, then left and right again, until the vehicle comes to rest at the emergency room back entrance of California Hospital, located at 1414 South Hope Street. The brick building appearing in the movie was completed in 1926, and demolished in 2000 after being damaged by the 1994 Northridge earthquake. A modern facility stands at the site today.

Traveling west along Venice Boulevard, the ambulance turns right at Grand, left at 15th Street, right at Catesby Lane, then left into the hospital receiving area. The top left image looks west down Venice, the middle image looks north up Grand, and the bottom image looks west down 15th.

Click to enlarge. Looking west down Venice Boulevard we see the extant Frank Dillin Building at 1601 S. Hope Street, and the back of the extant Essex Apartment building (box). USC Digital Library.

This view looks west up 15th Street (arrow) towards Hope Street before the ambulance turns right onto Catesby Lane, running behind the hospital. The same palm tree standing at the corner is marked in each image. LAPL.

Looking north, this 1960s aerial view shows the ambulance’s path. The box marks the extant Frank Dillin Building and the Essex Apartments on Hope Street. USC Digital Library.

A contemporary view – California Hospital has been greatly remodeled. The box marks the Frank Dillin Building and Essex Apartments on Hope Street. (C) 2014 Nokia. (C) 2014 Microsoft Corporation. Pictometry Bird’s Eye (C) 2012 Pictometry International Corp.

Night Nurse (C) 1931 Warner Bros. Vintage photos from the Los Angeles Public Library, the USC Digital Library, and the California State Library. Color views Google Street View (C) 2014 Google.

Looking east down Wilshire towards Dunsmuir today.

View Larger Map

Filed under: Pre-Code Tagged: Barbara Stanwyck, Ben Lyon, Clark Gable, Night Nurse, then and now, William Wellman, Wilshire Boulevard

November 2, 2014

How James Cagney Filmed Lady Killer

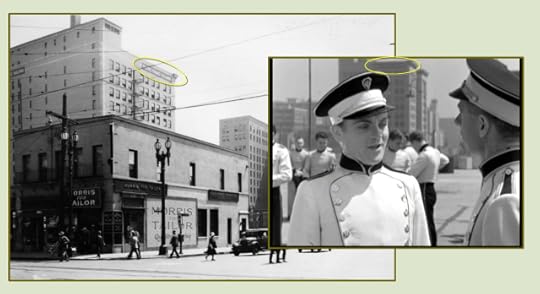

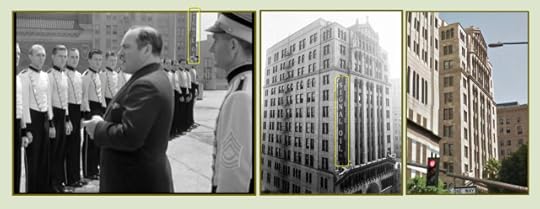

Click to enlarge this image and each image below. Which three of these buildings survive?

Eight downtown Los Angeles landmarks appear behind James Cagney during the opening scenes of Lady Killer (1933), yet only three survive to tell their tale. In this delightful pre-Code comedy/drama, Cagney plays Dan Quigley, a wise-cracking New York movie

Eight downtown Los Angeles landmarks appear behind James Cagney during the opening scenes of Lady Killer (1933), yet only three survive to tell their tale. In this delightful pre-Code comedy/drama, Cagney plays Dan Quigley, a wise-cracking New York movie  theater usher who falls in with a gang of crooks, and then flees to Los Angeles seeking a new life. Once there he stumbles into the movies and becomes an unlikely star, prompting the old gang to seek him out for blackmail and revenge. The movie opens with dozens of uniformed Warner Bros. movie theater ushers lining up for inspection on an open downtown rooftop. Jimmy arrives late as usual, but charms his way out of trouble.

theater usher who falls in with a gang of crooks, and then flees to Los Angeles seeking a new life. Once there he stumbles into the movies and becomes an unlikely star, prompting the old gang to seek him out for blackmail and revenge. The movie opens with dozens of uniformed Warner Bros. movie theater ushers lining up for inspection on an open downtown rooftop. Jimmy arrives late as usual, but charms his way out of trouble.

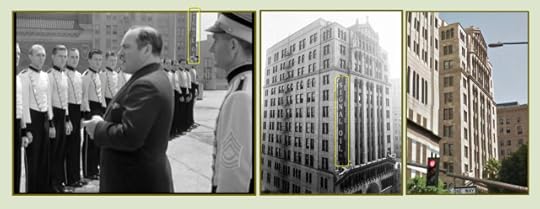

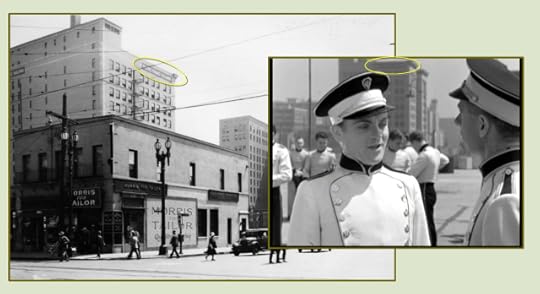

Who’s late for roll call? Cagney (arrow) and the WB ushers on the roof of the former Arnold Building auto dealership and parking garage at 7th, Figueroa, and Wilshire, (5) above on the map. LAPL.

The movie begins with the ushers lining up for inspection. The existing Barker Brothers Building, 818 W. 7th Street, (4) above, appears to the right. LAPL.

The Fine Arts Building, 811 W. 7th Street, (3) above, also known as the Signal Oil Building, also appears. LAPL.

Cagney runs past Los Angeles Fire Department Engine Co. No. 28, at 644 S. Figueroa, (6) above, now a restaurant. LOC.

When Jimmy dashes onto the roof from the stairwell shed, the former Bible Institute Building at 6th and Hope Street, (1) above, appears at back. LAPL. The building later installed a pair of large neon “JESUS SAVES” rooftop signs that became a downtown landmark. The orange oval marks the Bible Institute wall sign – the yellow oval marks the Pacific Finance Building wall sign discussed below.

The side of the former Pacific Finance Building, (2) above, appears at back. The building originally stood facing an alley that later became part of Wilshire Boulevard, when Wilshire was extended east from Figueroa to Grand during 1930-1931. The Pacific Finance Building was replaced by the 62 story First Interstate Bank Building, completed in 1973, and now called the Aon Center. LAPL.

The former Gates Hotel at 6th and Figueroa, (7) above, and former Richfield Building at 7th and Flower, (8) above, appear at back. The yellow oval marks the same letter “S” on the GATES rooftop neon sign. The Richfield Building, clad in black and gold terra cotta tile, was recognized as one of the great Art Deco masterpieces of modern architecture, but was sadly demolished in 1969. LAPL. LAPL.

This broad reverse view shows the stairwell shed on the roof of the Arnold Building garage (yellow box) from which Cagney emerges, as well as matching details on the back of the Gates Hotel (narrow yellow box). The red arrow marks the back of the LAFD Engine Co. No. 28 building, as it appears in the main photo, and the front as it appears in the movie. Directly above the red arrow stands the former St. Paul’s Cathedral that stood on Figueroa (1923-1980). LAPL.

Click to enlarge. This later aerial view shows the various buildings in relation to the Arnold Building roof (5), and the tower of the Los Angeles Public Library Building (circle). Note on the circa 1928 map that Wilshire Boulevard, to the left of the pink Arnold Building, then terminated at Figueroa. The aerial photo shows Wilshire (dotted yellow line) extending three blocks further from Figueroa to Grand, as completed during 1930-1931. USC Digital Library.

The now lost Statler. LAPL

The Arnold Building was demolished to make way for the ultra-modern Statler Hilton Hotel that opened in 1952, at the time the largest hotel built in the US since the Waldorf Astoria in 1931. The massive hotel, once a downtown landmark, was recently obliterated to make way for the new 70 story Wilshire Grand Center currently under construction and set to open in 2017. You can read all about the Statler Hotel’s demise at Steve Vaught’s entertaining and informative Hollywood architecture blog Paradise Leased.

Jimmy and Mae Clark flee “New York” for sunny California, as touted by this brochure (right), only to arrive by train during a thunderstorm. The establishing shot of their arrival, below, shows the back of the Santa Fe Depot that was used perhaps more often than any other station as a filming location. Harold Lloyd used the same station for scenes from both Girl Shy (1924) and Movie Crazy (1932), while this post shows how the station appears with Max Linder and Laurel & Hardy.

Jimmy and Mae Clark flee “New York” for sunny California, as touted by this brochure (right), only to arrive by train during a thunderstorm. The establishing shot of their arrival, below, shows the back of the Santa Fe Depot that was used perhaps more often than any other station as a filming location. Harold Lloyd used the same station for scenes from both Girl Shy (1924) and Movie Crazy (1932), while this post shows how the station appears with Max Linder and Laurel & Hardy.

Jimmy arrives in “sunny California” at the rear of the Santa Fe Depot, a very popular place to film that appears in dozens and dozens of films. This post shows how Max Linder and Laurel and Hardy also filmed at the same depot. USC Digital Library.

The gang fixes for Jimmy to be arrested on trumped up charges so they can follow and kill him after he is released from jail. Mae Clark posts Jimmy’s bail, and picks him up beside the Hall of Justice in downtown Los Angeles, the true setting where criminals were jailed at the time.

Cagney’s car pulls away from the Hall of Justice, on the corner of Broadway and Temple, towards the south face of the Broadway Tunnel. Completed in 1925, the recently refurbished Hall of Justice building reopened in 2014 after being shuttered for decades. While the building looks good as new, the Broadway Tunnel and its supporting hill were removed in 1949. USC Digital Library.

Despite initially being in on the plot to have Jimmy killed, Mae Clark warns him they are being followed, touching off a chase around Hollywood.

The action skips to Hollywood. Cagney and Mae Clark are chased down Vine Street from Hollywood Boulevard past what is now the Montalban Theater located at 1615 Vine Street (red box). LAPL.

A companion contemporary view looking north up Vine towards Hollywood Boulevard and the Montalban Theater (red box).

Next, the killers chase Cagney north up Wilcox, where he turns left, west, onto Sunset Blvd. The extant Hotel Wilcox appears up the street in each image (yellow box). Notice that Wilcox was not yet a through street when this aerial view at left was taken in 1928. Marc Wanamaker – Bison Archives; USC Digital Library.

Looking north up Wilcox from Sunset Boulevard today. The Hotel Wilcox is still standing up the street.

Following a prolonged chase and gun battle, the movie ends in true Hollywood fashion – the crooks are vanquished, Mae the gun moll is rehabilitated, and Jimmy resumes his film career and weds a movie star.

Following a prolonged chase and gun battle, the movie ends in true Hollywood fashion – the crooks are vanquished, Mae the gun moll is rehabilitated, and Jimmy resumes his film career and weds a movie star.

Wrapping up, Harold Lloyd filmed a number of early street scenes in Hollywood for his thrill comedy short Never Weaken (1921). The isolated shot below, edited to match with those filmed in Hollywood, was for some reason also filmed in downtown beside the Arnold Building, the same spot where Cagney would film on the roof a dozen years later.

Looking east along 7th Street toward the corner of Figueroa, with a matching view (inset) from Harold Lloyd’s Never Weaken. The Arnold Building, where Cagney filmed on the roof, stands to the left. The prominent Fine Arts Building, at the center, and the tall Barker Brothers Building, to the right, remain standing. USC Digital Library.

Lady Killer (C) 1933 Warner Bros. HAROLD LLOYD images and the names of Mr. Lloyd’s films are all trademarks and/or service marks of Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc. Images and movie frame images reproduced courtesy of The Harold Lloyd Trust and Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc.

Vintage photos from the Los Angeles Public Library, the USC Digital Library, and color views Google Street View (C) 2014 Google.

A view of the Barker Brothers Building.

View Larger Map

Filed under: James Cagney, Pre-Code Tagged: Arnold Building, Barker Brothers Building, Bible Institute, Broadway Tunnel, film noir locations, Fine Arts Building, Gates Hotel, Hall of Justice, Harold Lloyd, Hollywood, Hotel Wilcox, James Cagney, Lady Killer, LAFD Engine Co. 28, Los Angeles Historic Core, Mae Clark, Never Weaken, Pre-Code, Richfield Building, then and now, Vine Street, Warner Bros., Wilcox Avenue, Wilshire Boulevard

How James Cagney Filmed Lady Killer

Click to enlarge this image and each image below. Which three of these buildings survive?

Eight downtown Los Angeles landmarks appear behind James Cagney during the opening scenes of Lady Killer (1933), yet only three survive to tell their tale. In this delightful pre-Code comedy/drama, Cagney plays Dan Quigley, a wise-cracking New York movie

Eight downtown Los Angeles landmarks appear behind James Cagney during the opening scenes of Lady Killer (1933), yet only three survive to tell their tale. In this delightful pre-Code comedy/drama, Cagney plays Dan Quigley, a wise-cracking New York movie  theater usher who falls in with a gang of crooks, and then flees to Los Angeles seeking a new life. Once there he stumbles into the movies and becomes a star, prompting the old gang to seek him out for blackmail and revenge. The movie opens with dozens of uniformed Warner Bros. movie theater ushers lining up for inspection on an open downtown rooftop. Jimmy arrives late as usual, but charms his way out of trouble.

theater usher who falls in with a gang of crooks, and then flees to Los Angeles seeking a new life. Once there he stumbles into the movies and becomes a star, prompting the old gang to seek him out for blackmail and revenge. The movie opens with dozens of uniformed Warner Bros. movie theater ushers lining up for inspection on an open downtown rooftop. Jimmy arrives late as usual, but charms his way out of trouble.

Who’s late for roll call? Cagney (arrow) and the WB ushers on the roof of the former Arnold Building auto dealership and parking garage at 7th, Figueroa, and Wilshire, (5) above on the map. LAPL.

The movie begins with the ushers lining up for inspection. The existing Barker Brothers Building, 818 W. 7th Street, (4) above, appears to the right. LAPL.

The Fine Arts Building, 811 W. 7th Street, (3) above, also known as the Signal Oil Building, also appears. LAPL.

Cagney runs past Los Angeles Fire Department Engine Co. No. 28, at 644 S. Figueroa, (6) above, now a restaurant. LOC.

When Jimmy dashes onto the roof from the stairwell shed, the former Bible Institute Building at 6th and Hope Street, (1) above, appears at back. LAPL. The building later installed a pair of large neon “JESUS SAVES” rooftop signs that became a downtown landmark. The orange oval marks the Bible Institute wall sign – the yellow oval marks the Pacific Finance Building wall sign discussed below.

The side of the former Pacific Finance Building, (2) above, appears at back. The building originally stood facing an alley that later became part of Wilshire Boulevard, when Wilshire was extended east from Figueroa to Grand. The building was replaced by the 62 story First Interstate Bank Building, completed in 1973, and now called the Aon Center. LAPL.

The former Gates Hotel at 6th and Figueroa, (7) above, and former Richfield Building at 7th and Flower, (8) above, appear at back. The yellow oval marks the same letter “S” on the GATES rooftop neon sign. The Richfield Building, clad in black and gold terra cotta tile, was recognized as one of the great Art Deco masterpieces of modern architecture, but was sadly demolished in 1969. LAPL. LAPL.

This broad reverse view shows the stairwell shed on the roof of the Arnold Building garage (yellow box) from which Cagney emerges, as well as matching details on the back of the Gates Hotel (narrow yellow box). The red arrow marks the back of the LAFD Engine Co. No. 28 building, as it appears in the main photo, and the front as it appears in the movie. Directly above the red arrow stands the former St. Paul’s Cathedral that stood on Figueroa (1923-1980). LAPL.

Click to enlarge. This later aerial view shows the various buildings in relation to the Arnold Building roof (5), and the tower of the Los Angeles Public Library Building (circle). Note on the 1934 map that Wilshire Boulevard, to the left of the pink Arnold Building, then terminated at Figueroa. The aerial photo shows how Wilshire (dotted yellow line) was later extended three blocks further from Figueroa to Grand. USC Digital Library.

The now lost Statler. LAPL

The Arnold Building was demolished to make way for the ultra-modern Statler Hilton Hotel that opened in 1952, at the time the largest hotel built in the US since the Waldorf Astoria in 1931. The massive hotel, once a downtown landmark, was recently obliterated to make way for the new 70 story Wilshire Grand Center currently under construction and set to open in 2017. You can read all about the Statler Hotel’s demise at Steve Vaught’s entertaining and informative Hollywood architecture blog Paradise Leased.

Jimmy and Mae Clark flee “New York” for sunny California, as touted by this brochure (right), only to arrive by train during a thunderstorm. The establishing shot of their arrival, below, shows the back of the Santa Fe Depot that was used perhaps more often than any other station as a filming location. Harold Lloyd used the same station for scenes from both Girl Shy (1924) and Movie Crazy (1932), while this post shows how the station appears with Max Linder and Laurel & Hardy.

Jimmy and Mae Clark flee “New York” for sunny California, as touted by this brochure (right), only to arrive by train during a thunderstorm. The establishing shot of their arrival, below, shows the back of the Santa Fe Depot that was used perhaps more often than any other station as a filming location. Harold Lloyd used the same station for scenes from both Girl Shy (1924) and Movie Crazy (1932), while this post shows how the station appears with Max Linder and Laurel & Hardy.

Jimmy arrives in “sunny California” at the rear of the Santa Fe Depot, a very popular place to film that appears in dozens and dozens of films. This post shows how Max Linder and Laurel and Hardy also filmed at the same depot. USC Digital Library.

The gang fixes for Jimmy to be arrested on trumped up charges so they can follow and kill him after he is released from jail. Mae Clark posts Jimmy’s bail, and picks him up beside the Hall of Justice in downtown Los Angeles, the true setting where criminals were jailed at the time.

Cagney’s car pulls away from the Hall of Justice, on the corner of Broadway and Temple, towards the south face of the Broadway Tunnel. Completed in 1925, the recently refurbished Hall of Justice building reopened in 2014 after being shuttered for decades. While the building looks good as new, the Broadway Tunnel and its supporting hill were removed in 1949. USC Digital Library.

Despite initially being in on the plot to have Jimmy killed, Mae Clark warns him they are being followed, touching off a chase around Hollywood.

The action skips to Hollywood. Cagney and Mae Clark are chased down Vine Street from Hollywood Boulevard past what is now the Montalban Theater located at 1615 Vine Street (red box). LAPL.

A companion contemporary view looking north up Vine towards Hollywood Boulevard and the Montalban Theater (red box).

Next, the killers chase Cagney north up Wilcox, where he turns left, west, onto Sunset Blvd. The extant Hotel Wilcox appears up the street in each image (yellow box). Notice that Wilcox was not yet a through street when this aerial view at left was taken in 1928. Marc Wanamaker – Bison Archives; USC Digital Library.

Looking north up Wilcox from Sunset Boulevard today. The Hotel Wilcox is still standing up the street.

Following a prolonged chase and gun battle, the movie ends in true Hollywood fashion – the crooks are vanquished, Mae the gun moll is rehabilitated, and Jimmy resumes his film career and weds a movie star.

Following a prolonged chase and gun battle, the movie ends in true Hollywood fashion – the crooks are vanquished, Mae the gun moll is rehabilitated, and Jimmy resumes his film career and weds a movie star.

Wrapping up, Harold Lloyd filmed a number of early street scenes in Hollywood for his thrill comedy short Never Weaken (1921). The isolated shot below, edited to match with those filmed in Hollywood, was for some reason also filmed in downtown beside the Arnold Building, the same spot where Cagney would film on the roof a dozen years later.

Looking east along 7th Street toward the corner of Figueroa, with a matching view (inset) from Harold Lloyd’s Never Weaken. The Arnold Building, where Cagney filmed on the roof, stands to the left. The prominent Fine Arts Building, at the center, and the tall Barker Brothers Building, to the right, remain standing. USC Digital Library.

Lady Killer (C) 1933 Warner Bros. HAROLD LLOYD images and the names of Mr. Lloyd’s films are all trademarks and/or service marks of Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc. Images and movie frame images reproduced courtesy of The Harold Lloyd Trust and Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc.

Vintage photos from the Los Angeles Public Library, the USC Digital Library, and color views Google Street View (C) 2014 Google.

A view of the Barker Brothers Building.

View Larger Map

Filed under: James Cagney, Pre-Code Tagged: film noir locations, Harold Lloyd, Hollywood, James Cagney, Lady Killer, Los Angeles Historic Core, Mae Clark, Never Weaken, then and now, Warner Bros.

October 16, 2014

How Charlie Chaplin Filmed The Adventurer

Click to enlarge each view. Haystack Rock then and now – The Jeffrey Vance Collection (l) – David Totheroh (r)

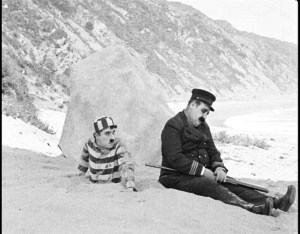

Here’s Charlie

Decades before Bugs Bunny delighted audiences by tunneling into strange predicaments, escaped convict Charlie Chaplin tunneled to freedom in The Adventurer (1917) on a Malibu beach within the shadow of Castle Rock and Haystack Rock, prominent coastal landmarks that stood near the dusty dirt road that would one day become the Pacific Coast Highway. The Adventurer, and Chaplin’s other eleven short comedies prepared for the Mutual Film Corporation, have all been lovingly restored on Blu-ray, available from Flicker Alley.

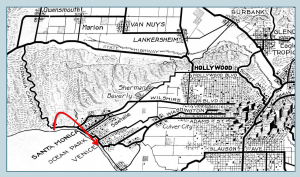

Chaplin filmed early scenes near the mouth of Topanga Canyon, and the related swimming scenes in Venice.

When Chaplin filmed here in 1917, most of Malibu remained privately owned by May Rindge, widow of wealthy ranch owner Frederick Ringe. The public coastline road only traveled as far west as Topanga Canyon before it was forced to turn inland. Ms. Rindge battled in court for decades to protect her massive land holdings, bankrupting herself in the process, but in 1923 the US Supreme Court upheld California’s eminent domain powers, leading to the construction of the Roosevelt Highway (later Pacific Coast Highway) along her coastal land, that opened in 1929. As explained in greater detail in my book Silent Traces, Chaplin filmed the initial beach scenes here, and the later scenes where he rescues Edna Purviance and others from the water in Venice to the south.

Looking east to the Castle Rock filming site. The Pacific Coast Highway traversing Malibu (see Charlie’s dirt road at left) would not be built for years. Castle Rock towers at center – Haystack Rock appears to the right. USC Digital Library

Then and Then – USC Digital Library

Another view of the filming area after the road was paved. This was likely taken before the Pacific Coast Highway opened in 1929. The coast road originally had to turn inland at Topanga Canyon because the Malibu shore was privately owned. USC Digital Library

The Adventurer – then and now. Jeffrey Castel De Oro

A side view of Haystack Rock (l) as it appears in Chaplin’s Burlesque on Carmen (1915), and as it appears today (r). Chaplin’s publicity shot for The Adventurer (center) was staged in front of Haystack Rock. Current view Jeffrey Castel De Oro.

The Castle Rock beach was an extremely popular place to film. Now looking west, in the opposite direction toward Castle Rock, is a “Bathing Beauty” beach scene from the Mack Sennett comedy Hearts and Flowers (1919) available on the new CineMuseum Blu-ray release The Mack Sennett Collection available from Flicker Alley. USC Digital Library

Looking west, Charlie eludes the police likely where Coastline Drive meets the Pacific Coast Highway. (C) Microsoft Corporation.

A modern view showing Coastline Drive (l), Haystack Rock (center), the former Castle Rock site (it was leveled in 1945 as a safety measure), and the Chaplin filming site (r). (C) 2014 Google

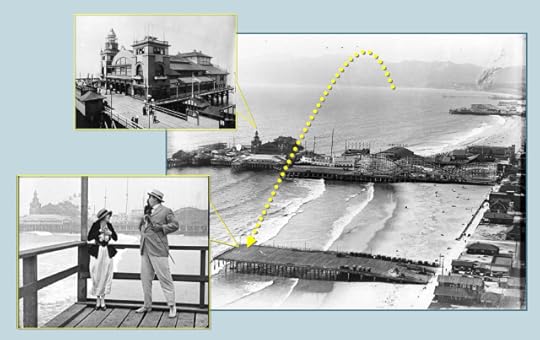

The action jumps from Malibu to the Abbot Kinney Pier in Venice. The tower of the Venice Auditorium (USC Digital Library) appears behind Edna Purviance and Eric Campbell. Marc Wanamaker – Bison Archives

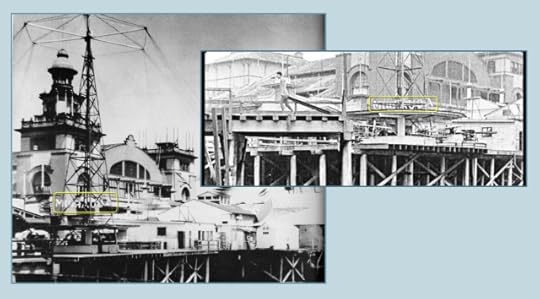

Click to enlarge. With clever editing, Charlie dumps Eric into the water from the Center Street Pier (lower left), yet Eric hits the water beside the Abbot Kinney Pier (upper left).

A reverse view of Eric’s bifurcated spill into the water. The Abbot Kinney Pier would burn almost completely a few days after this photo was taken in 1920. It was quickly rebuilt in 1921. Marc Wanamaker – Bison Archives

The front of the Venice Auditorium appears in both images, along with a “MUIRAUQA” sign, the back of the illuminated sign for the Venice AQUARIUM. LAPL

This view from Harold Lloyd’s 1920 short comedy Number Please? shows the same AQUARIUM sign as it appeared to the public strolling down the pier. The inset view looks the other way. LAPL

The Abbot Kinney Pier burned in late 1920, but was quickly rebuilt in 1921. The re-built pier appears prominently during Chaplin’s 1928 feature comedy The Circus. Following years of decline, and subsequent fires, the pier was closed and demolished in 1946. Chaplin also filmed Kid Auto Races at Venice Cal. (1914) (see blog post HERE) and By The Sea (1915) in Venice. All three films are also discussed in my book Silent Traces.

The Adventurer (1917) from the new Blu-ray release Chaplin’s Mutual Comedies 1916-1917. All images from Chaplin films made from 1918 onwards, copyright © Roy Export Company Establishment. CHARLES CHAPLIN, CHAPLIN, and the LITTLE TRAMP, photographs from and the names of Mr. Chaplin’s films are trademarks and/or service marks of Bubbles Incorporated SA and/or Roy Export Company Establishment. Used with permission. Hearts and Flowers (1919) from the new Blu-ray release The Mack Sennett Collection Vol. One. Number Please? (1920) HAROLD LLOYD images and the names of Mr. Lloyd’s films are all trademarks and/or service marks of Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc. Images and movie frame images reproduced courtesy of The Harold Lloyd Trust and Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc.

View Larger Map

Filed under: Charlie Chaplin Tagged: Chaplin Locations, Chaplin Tour, Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, Hollywood, Number Please?, Silent Comedians, Silent Comedies, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, The Adventurer, then and now

September 28, 2014

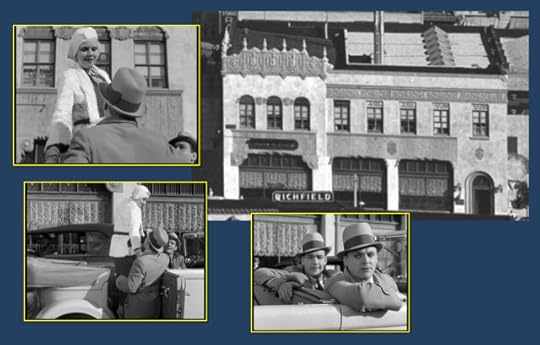

Cagney and Harlow on The Public Enemy’s Miracle Mile

Click to enlarge each image. James Cagney slows down to check out Jean Harlow. The view looks east down Wilshire Boulevard from Detroit Street towards the E. Clem Wilson Building on the corner of La Brea.

Thanks to the Turner Classic Movie Channel’s Pre-Code Festival this past month, I’ve been able to catch many great films for the first time, including the topic of this post, The Public Enemy (1931). Much has been written about this film, including the shocking scene where Cagney smashes a

Thanks to the Turner Classic Movie Channel’s Pre-Code Festival this past month, I’ve been able to catch many great films for the first time, including the topic of this post, The Public Enemy (1931). Much has been written about this film, including the shocking scene where Cagney smashes a  grapefruit into Mae Clarke’s face. I’ll leave the commentary to others, but as a fan of early Los Angeles, I was intrigued to discover a key scene, where Cagney picks up Jean Harlow on the street, was filmed along a couple of blocks of the Wilshire Boulevard shopping district known as the “Miracle Mile.”

grapefruit into Mae Clarke’s face. I’ll leave the commentary to others, but as a fan of early Los Angeles, I was intrigued to discover a key scene, where Cagney picks up Jean Harlow on the street, was filmed along a couple of blocks of the Wilshire Boulevard shopping district known as the “Miracle Mile.”

Cagney and his buddy played by Edward Woods drive south down Detroit Street crossing Wilshire. The Wilshire Manor Apartments (oval) stand at back.

This aerial view shows Cagney’s path down Detroit across Wilshire.

Cagney slows down to check out Jean Harlow. The view looks east down Wilshire from Detroit. The right image shows detail of the E. Clem Wilson Building.

This front view of Harlow, supposedly on the same corner of Detroit, was filmed one block further west, at the corner of Cloverdale Avenue, in front of the Dominguez Building. The real estate ad behind Jean also appears in this vintage view.

Looking west at the Dominguez Building.

Cagney stopped at the corner of Detroit (above). Harlow is introduced in closeup standing on Wilshire, near the same corner. Behind her, looking to the NW, are buildings (callout box) on the north side of Wilshire.

The Tip Top Sandwich shop, behind Jean’s shoulder, formerly occupied 5367 Wilshire. The remodeled building now hosts a Subway sandwich shop nearby.

Cagney convinces Jean to allow him to give her a ride. These views show details on the building standing on the SE corner of Wilshire and Detroit.

A modern view of the same corner. The window and door patterns of the brick building remain the same, so apparently it is the same building, stripped of all ornamentation.

Edward Woods plays chauffeur, driving Cagney and Harlow along side this beautiful building now lost to history. Notice the matching “NUTS” sign detail. The view looks toward the NE corner of Wilshire and Hauser, six blocks west of Detroit. A Pig ‘N Whistle restaurant stood on this corner during filming – the words barely appear on the awning as they drive by.

Continuing driving west along Wilshire from Hauser, the car passes an existing store, home to a Safeway at the time of filming, and to a “Pay n Takit” store in the vintage photo. It is now an IHOP restaurant.

Cagney drops Harlow off at Wilshire, west of the corner of Dunsmuir, with the Wilshire Tower Building in the background.

Delighted to get Jean Harlow’s phone number, Cagney dances a little jig, sadly blocked from view by extras walking in front of the camera. The Oscar Balzer shop appears in both images.

The Public Enemy (C) 1931 Warner Bros.

The Public Enemy (C) 1931 Warner Bros.

Vintage photos from the Los Angeles Public Library, the USC Digital Archive, and the California State Library.

A view of the intersection of Wilshire and Detroit today.

View Larger Map

Filed under: Uncategorized Tagged: James Cagney, Jean Harlow, Pre-Code, the Miracle Mile, The Public Enemy, William Wellman, Wilshire Boulevard

September 25, 2014

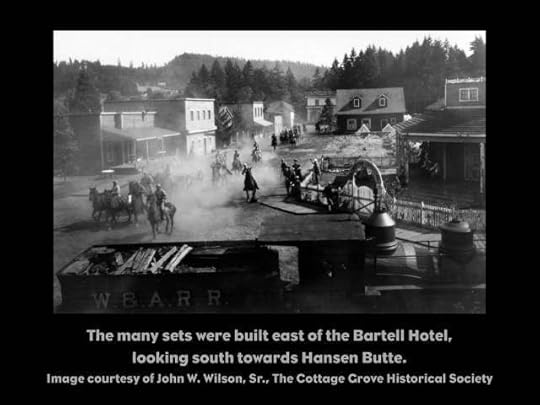

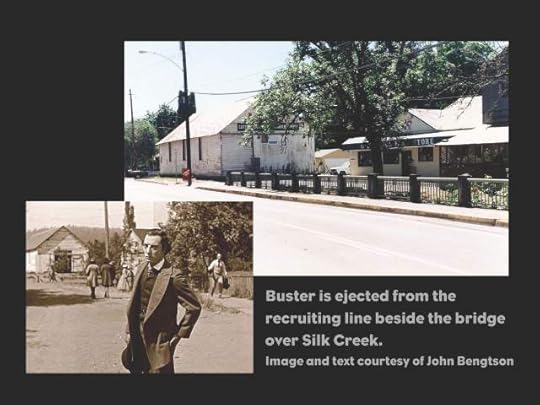

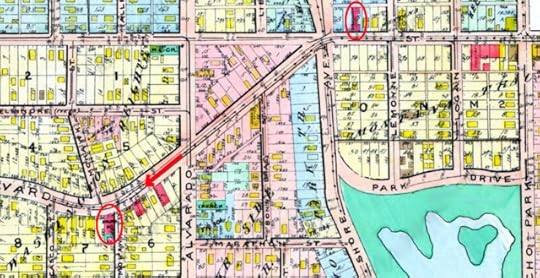

How Buster Keaton Filmed The General

Click to enlarge. Buster and crew stayed at the Bartell Hotel (1), steps from the Union Camp set (2) built north of the tracks and filmed looking north, (3) the half-mile length of parallel train tracks (dotted line) used for all of the tracking shots, all filmed looking south (4) the open field (green outline) between Main Street and the tracks, used for the Confederate army retreat, filmed looking south, and (5), the Marietta and Chattanooga town sets, built south of the tracks and filmed looking south. (C) 2014 Nokia (C) 2014 Microsoft Corporation Pictometry Bird’s Eye (C) 2012 MDA Geospatial Services Inc.

I had the honor of introducing Buster Keaton’s 1926 masterpiece The General at the San Francisco Silent Film Festival’s inaugural Silent Autumn Festival this past September 20, 2014. Preceding the show, these informational slides (below) prepared by the festival’s Artistic Director Anita Monga, ran on a loop as people took their seats. Although Keaton had to travel 900 miles north from Hollywood to Cottage Grove, Oregon to film The General, the vast majority of the location shooting took place just steps from the hotel where Buster stayed (above).

This brief video hosted by A.M.P.A.S. from a talk I gave in 2011 further explains how Buster filmed The General in Cottage Grove. You can read all about filming The General in my Keaton film locations book Silent Echoes.

This brief video hosted by A.M.P.A.S. from a talk I gave in 2011 further explains how Buster filmed The General in Cottage Grove. You can read all about filming The General in my Keaton film locations book Silent Echoes.

The Bartell Hotel building in Cottage Grove where Keaton and crew stayed during the production.

View Larger Map

Filed under: Buster Keaton, The General Tagged: Buster Keaton, Cottage Grove, How Buster Keaton filmed The General, Keaton Locations, Keaton Studio, San Francisco Silent Film Festival, Silent Comedians, Silent Comedies, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, The General, then and now

September 8, 2014

Keaton’s The General on location in Cottage Grove

The San Francisco Silent Film Festival special one-day “Silent Autumn” event opens Saturday morning, September 20, 2014, with a trio of classic Laurel & Hardy silent shorts, and features a 7:00 p.m. screening of Buster Keaton’s 1926 Civil War masterpiece The General, accompanied by the Alloy Orchestra.

The San Francisco Silent Film Festival special one-day “Silent Autumn” event opens Saturday morning, September 20, 2014, with a trio of classic Laurel & Hardy silent shorts, and features a 7:00 p.m. screening of Buster Keaton’s 1926 Civil War masterpiece The General, accompanied by the Alloy Orchestra.

Keaton filmed The General nearly 90 years ago on location in Cottage Grove, Oregon. Not only do many locations that appear in the movie remain unchanged, but as explained in this brief video hosted by A.M.P.A.S., you can see that most of the filming took place within steps of the hotel where Keaton and crew stayed during production.

Keaton filmed The General nearly 90 years ago on location in Cottage Grove, Oregon. Not only do many locations that appear in the movie remain unchanged, but as explained in this brief video hosted by A.M.P.A.S., you can see that most of the filming took place within steps of the hotel where Keaton and crew stayed during production.

Then and Now – 221 South 16th Street in Cottage Grove, Oregon, appears behind Buster during filming.

The Silent Autumn festival also includes Rudolph Valentino in The Son of the Sheik, a typical cinema program from 1914, the year Charlie Chaplin began making movies, and the influential German horror film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.

You can read more about how Keaton filmed The General and his other classic comedies in my book Silent Echoes.

The General is available on Blu-ray from Kino International, and includes a bonus program that I prepared. Below, a Google Street View of the above filming site.

View Larger Map

Filed under: Buster Keaton, The General Tagged: Buster Keaton, Cottage Grove, San Francisco Silent Film Festival, Silent Comedians, Silent Comedies, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, The General, then and now

August 27, 2014

Silent Era Hollywood Tour – Cinecon 50 – Author Presentation

Attached to this post is a self-guided written tour to Hollywood silent film locations and studios that I have prepared in connection with the “Hollywood’s Silent Echoes” presentation I will be giving Friday, August 29, 2014, at 10:55 a.m. at the Egyptian Theater, 6712 Hollywood Boulevard, as part of the Cinecon 50 – Classic Film Festival. With this tour you can follow a number of points I will cover during my presentation.

Attached to this post is a self-guided written tour to Hollywood silent film locations and studios that I have prepared in connection with the “Hollywood’s Silent Echoes” presentation I will be giving Friday, August 29, 2014, at 10:55 a.m. at the Egyptian Theater, 6712 Hollywood Boulevard, as part of the Cinecon 50 – Classic Film Festival. With this tour you can follow a number of points I will cover during my presentation.

The written tour starts at Hollywood and Vine, and encompasses nearly 50 filming locations and historic sites associated with Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, Stan Laurel, and Harry Langdon, including several new discoveries not found in my books or previously posted tours.

The written tour starts at Hollywood and Vine, and encompasses nearly 50 filming locations and historic sites associated with Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, Stan Laurel, and Harry Langdon, including several new discoveries not found in my books or previously posted tours.

Aside from early Hollywood, my talk this year will focus on Chaplin’s origins and some interesting connections between D.W. Griffith and Buster Keaton.

During the lunch break after my talk I will lead a quick walking tour from the theater of the historic 1600 block of Cahuenga nearby. I look forward to seeing you at Cinecon 50!

Hollywood’s Silent Echoes Tour – Cinecon 2014 – John Bengtson

Filed under: Chaplin Tour, Keaton Tour, Lloyd Tour Tagged: Buster Keaton, Chaplin Locations, Chaplin Studio, Chaplin Tour, Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, Harold Lloyd, Harry Langdon, Hollywood, Hollywood Tour, Keaton Locations, Keaton Studio, Lloyd Studio, Silent Comedians, Silent Comedies, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, then and now

August 11, 2014

Charlie Chaplin’s Echo Park Home – 100 Years Later

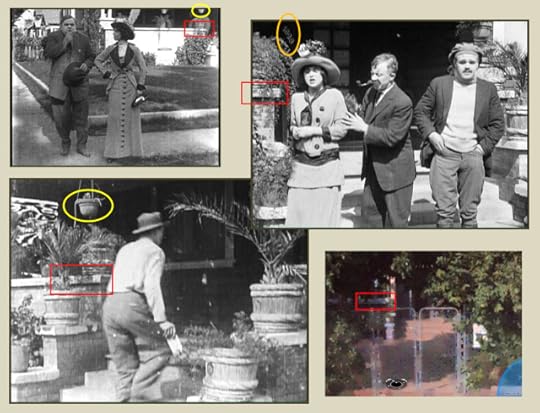

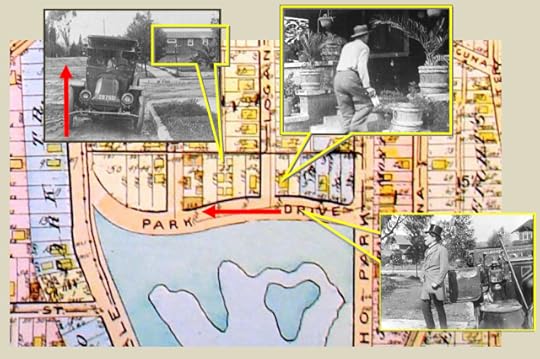

Cruel, Cruel Love – Charlie’s handyman races up the steps to 1629 Park Avenue (center), also appearing behind Chaplin (oval) as he stands at the NE corner of Echo Park.

Mabel Normand, Chaplin, Mack Swain, and Eva Nelson in Mabel’s Married Life (1914) beside the Echo Park bridge.

As I explain in my book Silent Traces, Charlie Chaplin filmed several early comedies in Echo Park, just a few blocks south of the Keystone Studio where he began his film career 100 years ago. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it turns out that Chaplin and other Keystone stars also filmed beside homes that are still standing directly across the street from the park. As shown above and elsewhere below, Chaplin’s home in Cruel, Cruel Love (1914) is located at 1629 Park Avenue, at the NE corner of Logan Street. Other remaining homes along Park Avenue appear in Keystone films too (see below), standing just a few blocks east from where Chaplin filmed on Sunset Boulevard 100 years ago, as reported HERE.

Looking west along Park Ave. from Logan St. – scenes from A Film Johnnie (left) and A Flirt’s Mistake (right).

I began paying attention to the front porches appearing in early Keystone films after noticing that a dozen other movies were shot beside the front porch where Chaplin filmed the initial scene of his career (as reported HERE).

I began paying attention to the front porches appearing in early Keystone films after noticing that a dozen other movies were shot beside the front porch where Chaplin filmed the initial scene of his career (as reported HERE).

The porch in the Chaplin/Mabel Normand comedy Mabel at the Wheel (1914) reveals a “1629” address and an array of distinctive potted plants that clearly matches Chaplin’s porch in Cruel, Cruel Love (see below).

Click to enlarge. Four views of the 1629 Park Ave. porch, now closed over; clockwise from upper left, Roscoe Arbuckle in A Flirt’s Mistake, Mabel Normand in Mabel at the Wheel, today, and Cruel, Cruel Love.

I also noticed a group of small bungalows that appears both in Cruel, Cruel Love and in Chaplin’s A Film Johnnie (1914), that reveal a street corner consistent in appearance to a corner appearing in the Roscoe Arbuckle comedy A Flirt’s Mistake (1914). The Arbuckle corner reveals a street sign reading “Park Ave” (see below).

Click to enlarge. Matching views from Cruel, Cruel Love (top), A Film Johnnie (bottom) and A Flirt’s Mistake (right). The street sign (orange oval) reads “Park Ave.”

Although hard to spot at first, I finally noticed that Chaplin’s “potted plant” porch also appears in A Flirt’s Mistake (see above), tying the pieces together. So on a hunch, I researched “Park Ave” in connection with the 1629 “potted plant” address, and found that Chaplin’s Cruel, Cruel Love home is still standing due north of Echo Park at 1629 Park Avenue.

Cruel, Cruel Love – Chaplin’s handyman runs along the north edge of Echo Park. The home on the NW corner of Park and Logan (oval) is still standing.

Remarkably, a second home appearing both in Cruel, Cruel Love and in A Flirt’s Mistake, at the NW corner of Park and Logan, is also still standing (see above), as is the group of bungalows, just up the street, at what was originally 1711 – 1715 Park Ave (see below).

Cruel, Cruel Love (top), A Film Johnnie (bottom). Between the bungalows and the corner home, on what was a vacant lot during the 1914 filming, is an apartment block (oval) built in the 1920s.

Two views from A Flirt’s Mistake keyed to north up Logan Street. 1629 Park Ave. stands to the right.

Below is a broad overview of the filming sites related to the north end of Echo Park. The arrow points west along Park Avenue past the corner of Logan.

Click to enlarge. Three views from Cruel, Cruel Love; looking west past Logan from Park, looking at the porch of 1629 Park Ave., and a view from the corner of Echo Park towards 1629 Park Ave.

Click to enlarge. Perhaps most remarkably, when an ambulance arrives at Charlie’s home during Cruel, Cruel Love, the camera looks due west along Park Avenue, past Echo Park to the left (south), towards vintage homes on a hill in the far background (yellow ovals) that are still standing on N. Bonnie Brae Street. I can’t identify the homes positively, but they are likely among the four pictured here at the upper right.

These ovals mark where Chaplin filmed on Sunset Blvd, just a few blocks west from Echo Park

Chaplin at Keystone: Copyright (C) 2010 by Lobster Films for the Chaplin Keystone Project. Today photos Copyright (C) 2014 Google Inc.; Bing Maps Bird’s Eye – (C) 2014 NAVTEQ, Pictometry Bird’s Eye (C) 2014 Pictometry International Corp., (C) 2014 Microsoft Corporation.

1629 Park Avenue on Google Street View.

View Larger Map

Filed under: Chaplin Tour, Charlie Chaplin, Keystone Studio Tagged: A Film Johnnie, A Flirt's Mistake, Chaplin Locations, Charlie Chaplin, Cruel Cruel Love, Echo Park, Keystone Studio, Mabel Normand, Roscoe Arbuckle, Silent Comedians, Silent Comedies, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, then and now