John Bengtson's Blog, page 2

May 31, 2024

Monty Banks ‘Peaceful Alley’ beside Pickford, Chaplin, Keaton, and Lloyd

Cheerful, dapper, always smiling, winking, performing pratfalls and dangerous stunts tirelessly in dozens of films, silent comedian/director Monty Banks is a revelation. Born Mario Bianchi in Italy in 1897, he started in films in 1916, before Buster Keaton, and made more feature silent comedy films than Harry Langdon. And he filmed everywhere, all across soon to be widely-known Hollywood and LA locations, often before other silent film stars filmed there too. While perhaps more silly fun than high art, his movies are thrilling and enjoyable. David Wyatt (sadly now deceased) and David Glass have released a truly splendid Blu-ray Kickstarter set of Monty’s rare and restored films, for which I was honored to contribute several location bonus programs. So expect more blogs about Monty in the weeks to come.

Cheerful, dapper, always smiling, winking, performing pratfalls and dangerous stunts tirelessly in dozens of films, silent comedian/director Monty Banks is a revelation. Born Mario Bianchi in Italy in 1897, he started in films in 1916, before Buster Keaton, and made more feature silent comedy films than Harry Langdon. And he filmed everywhere, all across soon to be widely-known Hollywood and LA locations, often before other silent film stars filmed there too. While perhaps more silly fun than high art, his movies are thrilling and enjoyable. David Wyatt (sadly now deceased) and David Glass have released a truly splendid Blu-ray Kickstarter set of Monty’s rare and restored films, for which I was honored to contribute several location bonus programs. So expect more blogs about Monty in the weeks to come.

Above the Third St Tunnel – a typical Monty stunt climbing scene Paging Love (1923)

But here’s what I find most amazing about Monty. Pick any film and it is bound to be loaded with locations and early visual history. This post studies fragments of but a single film, Monty’s 1921 comedy Peaceful Alley, which remarkably was presented as part of a (1990s ?) Czech television tribute “The Alphabet of Humor- Monty Banks the Comedian and his World” hosted on YouTube – starting at 01:14 link HERE. In just this one single film Monty crosses paths with Mary Pickford, Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, D. W. Griffith, and others, and provides unique points of view for scenes from Charlie Chaplin’s The Kid.

But here’s what I find most amazing about Monty. Pick any film and it is bound to be loaded with locations and early visual history. This post studies fragments of but a single film, Monty’s 1921 comedy Peaceful Alley, which remarkably was presented as part of a (1990s ?) Czech television tribute “The Alphabet of Humor- Monty Banks the Comedian and his World” hosted on YouTube – starting at 01:14 link HERE. In just this one single film Monty crosses paths with Mary Pickford, Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, D. W. Griffith, and others, and provides unique points of view for scenes from Charlie Chaplin’s The Kid.

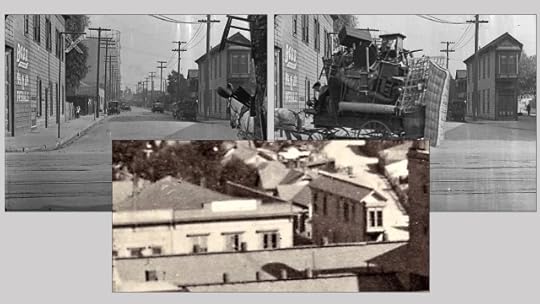

To begin, looking south, Monty filmed this scene from Peaceful Alley at the urban “Y” shaped intersection backlot set at the Brunton (later United, then Paramount) Studio.

To begin, looking south, Monty filmed this scene from Peaceful Alley at the urban “Y” shaped intersection backlot set at the Brunton (later United, then Paramount) Studio.

Above, views of the same “Y” intersection set appearing in Mary Pickford’s 1919 The Hoodlum (left) and in Buster Keaton’s 1922 Day Dreams. You can read all about this frequently used backlot set in this prior post Mary Pickford, the Talmadge Sisters, and Buster Keaton at the Brunton Studio.

Above left, now looking NW, Monty flees the police toward the main branch of the “Y” intersection, matching Buster’s ladder stunt scene from Cops (1922). Monty is running past the “Money To Loan” pawn shop (visible in the Cops frame – click to enlarge) where Buster mistakenly “purchased” a horse and wagon for $5.00.

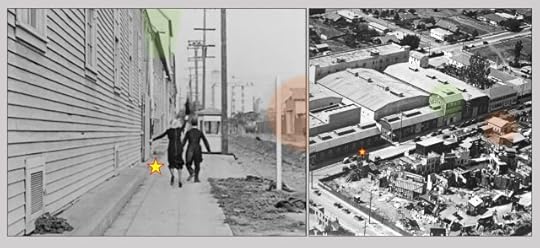

Next during Peaceful Alley, Monty runs past a distinctive narrow street corner.

Next during Peaceful Alley, Monty runs past a distinctive narrow street corner.

Above left, looking west, reveals the now lost corner of Alameda (left) and Los Angeles St (right). Here Harold Lloyd joins the fun. Harold filmed at least three comedies here, That’s Him in 1918, and the 1919 comedies Off the Trolley, and above right From Hand to Mouth.

Above, left and right, Snub Pollard filmed Fifteen Minutes here in 1921, while Larry Semon (center) filmed Frauds and Frenzies (1918) at the same spot. Visually distinctive street corners, allowing the audience to see cops and comedians on the opposite sides, unaware of each other before slamming into each other, were very popular gags. You can read all about this frequently filmed location here Silent Comedy’s Crazy Corner. Early in my research it felt like a lucky coincidence if more than one comedian used the same location. But having documented at least seven comedies filmed at this corner (likely many more), it’s increasingly clear such locations were commonly known and shared within the small, tightly-knit film community

Now a few blocks south from the Los Angeles St corner, Monty filmed scenes looking east beside the now lost 412 Ducommun Street triangle building near the corner of Alameda. Monty is peeking down Labory Lane to the right, the towering Ducommun gas plant holding tank appears at left.

Now a few blocks south from the Los Angeles St corner, Monty filmed scenes looking east beside the now lost 412 Ducommun Street triangle building near the corner of Alameda. Monty is peeking down Labory Lane to the right, the towering Ducommun gas plant holding tank appears at left.

Above, two views of the 412 Ducommun Street triangle building from Cops with an inset from an 1897 photo!

Above, two views of the 412 Ducommun Street triangle building from Cops with an inset from an 1897 photo!

More views of this once very popular filming site before it was demolished around 1923. Above left, Robert Harron in D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance (1916), and another appearance with Monty jumping between moving vehicles in Derby Day (1922). This triangle building appeared in many other films – you can read more here The Kid, Cops, Intolerance revealed in a 125 year old photo.

This view from Peaceful Alley looks east down Labory Lane toward the Amelia Street Public School at back, now all lost.

This view from Peaceful Alley looks east down Labory Lane toward the Amelia Street Public School at back, now all lost.

Charlie Chaplin now joins the action. Above, during The Kid (1921) Charlie filmed scenes rescuing Jackie Coogan from the orphanage truck looking east down Labory Lane, with the Ducommun gas holding tank and Amelia Street school at back.

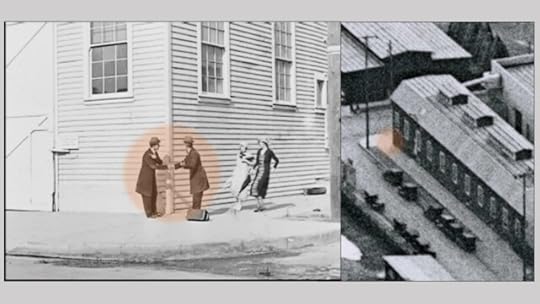

Above – Peaceful Alley, Monty plots to retrieve collected rent money stolen by William Blaisdell – Marc Wanamaker Bison Archives.

Above – Peaceful Alley, Monty plots to retrieve collected rent money stolen by William Blaisdell – Marc Wanamaker Bison Archives.

The Peaceful Alley scene above (left) shows the other side of the brick wall where Albert Austin and A. Thalasso discover the abandoned baby in their stolen car during The Kid (right). Both scenes were filmed beside a rail spur branching off from the main rail line along Alameda, next to a crumbling brick wall, in back of the former Rescue Mission, all now lost.

These views from Peaceful Alley (left) and The Kid (right) show matching views of the same crumbling brick wall from both sides. An earlier post reveals wide vintage photos of this location – read more at Chaplin falls for The Kid – every scene now identified.

Updating my previous post about Silent Comedy’s Bridges of Hollenbeck Park, the recent three-disc Kino-Lorber Vitagraph Comedies Blu-ray release, featuring over 40 Vitagraph Studio comedies filmed between 1907-1922, includes a segment from the 1918 Larry Semon comedy Hindoos and Hazards featured below.

Updating my previous post about Silent Comedy’s Bridges of Hollenbeck Park, the recent three-disc Kino-Lorber Vitagraph Comedies Blu-ray release, featuring over 40 Vitagraph Studio comedies filmed between 1907-1922, includes a segment from the 1918 Larry Semon comedy Hindoos and Hazards featured below.

Above, two views of the former Hollenbeck Park arched bridge appearing in Hindoos and Hazards, as Larry escapes one pursuer by tricking him to dive at him, only to miss and fall off the bridge.

So much of early LA is lost, demolished, built over. But as more and more silent movies become available on home video releases and on YouTube, the interplay between such films grows stronger. As seen in this post, Monty Banks filmed Peaceful Alley everywhere, and with just one single movie has provided overlapping images of once commonly used locations, while providing a deeper and wider window into the past.

So much of early LA is lost, demolished, built over. But as more and more silent movies become available on home video releases and on YouTube, the interplay between such films grows stronger. As seen in this post, Monty Banks filmed Peaceful Alley everywhere, and with just one single movie has provided overlapping images of once commonly used locations, while providing a deeper and wider window into the past.

Check out my new YouTube video Caught On Film – Buster Keaton’s The Cameraman. Not just the locations, moving to M-G-M, and Buster’s rented bungalow right outside, but hidden details reveal how filming at long-familiar locales, and near where he had once worked happily with mentor/best friend Roscoe Arbuckle, must have given Keaton some comfort during this difficult transition in life. Score by Jon C. Mirsalis.

April 27, 2024

Silent Comedy’s Bridges of Hollenbeck Park

The graceful arch bridge that once spanned the narrow lake in Hollenbeck Park has appeared in numerous silent films. USC Digital Library.

The graceful arch bridge that once spanned the narrow lake in Hollenbeck Park has appeared in numerous silent films. USC Digital Library.

Perhaps its most celebrated appearance is with Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy during their early talkie short Men ‘O War (1929), when the bridge appears at back while they flirt with Gloria Greer and Anne Cornwall.

Years earlier, in 1920 Harold Lloyd attempted to end it all by leaping from the bridge during Haunted Spooks (above left, looking north), and returned in 1924 to film this scene from Girl Shy (above right), looking south toward the bridge.

Harold also posed beside the arched bridge for this early 1915 Lonesome Luke comedy Great While It Lasted.

Harold also posed beside the arched bridge for this early 1915 Lonesome Luke comedy Great While It Lasted.

Hollenbeck Park appears in splendid detail throughout the 1920 Snub Pollard comedy Run ‘Em Ragged, hosted on YouTube by Leeweegie1960, including views of the bridge starting at 15:14 HERE.

During the 1916 comedy Picture Pirates, Ben Turpin (center in above left image) and his cohorts flee the police. Some cops lose their trail by running over the bridge instead, the earliest footage I’ve seen of the bridge from this angle. Once again hosted by Joseph Blough’s wonderful YouTube channel, you can watch the scene starting at 06:07 HERE. Looking west from the lake’s east side, this scene was filmed in the morning. (Filming on the west side of the lake looking east is more common as it provides for a longer shooting day). Scientists may prove me wrong, but to my eye morning scenes in silent films appear bright and cool (see above), while afternoon scenes appear warm. Flawed science or not, based on whether a scene looks cool or warm, morning or afternoon, and therefore west or east, has provided accurate geographic clues from which I have discovered many locations.

Final views of the arched bridge, this time in the 1920 Kewpie Morgan comedy The Heart Snatcher, above left. Hosted by the Eye Filmmuseum YouTube channel you can watch the scene, beginning at 08:45 HERE. Above right, Snub Pollard in The Butterfly Hunter, hosted by Extreme Mysteries YouTube channel, the scene starting at 0:58 HERE.

Further south, the 6th Street bridge for automobiles that once spanned the park and the lake below, also appears in numerous films. Whenever a hero or a comedian leaps from a bridge during a silent movie it was likely filmed here. The bridge was the optimal height for the leap to appear thrilling on screen without inconveniently killing the performer. USC Digital Library.

Further south, the 6th Street bridge for automobiles that once spanned the park and the lake below, also appears in numerous films. Whenever a hero or a comedian leaps from a bridge during a silent movie it was likely filmed here. The bridge was the optimal height for the leap to appear thrilling on screen without inconveniently killing the performer. USC Digital Library.

To begin, look who’s back. That’s Ben Turpin (above left, on the right) once again in Picture Pirates, leaping off the bridge to escape the police. (I can’t say whether someone doubled for Ben during the jump or not). You can watch the scene starting at 06:28 HERE.

Another thrilling stunt, from the Looser Than Loose DVD set Larry Semon: An Underrated Genius, during Scamps and Scandals (1919) Larry Semon (or perhaps his double) dives from the 6th Street Bridge. Notice Larry beside the same telephone pole next to Ben Turpin above. Just for fun they installed a platform on the pole to make the dive that much higher. While the image could be more clear, the dive really took place, ending with a convincing splash in the water.

Another thrilling stunt, from the Looser Than Loose DVD set Larry Semon: An Underrated Genius, during Scamps and Scandals (1919) Larry Semon (or perhaps his double) dives from the 6th Street Bridge. Notice Larry beside the same telephone pole next to Ben Turpin above. Just for fun they installed a platform on the pole to make the dive that much higher. While the image could be more clear, the dive really took place, ending with a convincing splash in the water.

Next, during the Our Gang 1928 comedy The Ol’ Gray Hoss, the dismissive big kids tell young Wheezer to go jump in a lake, which he promptly obeys by falling from the 6th Street Bridge.

The terrified big kids, who dive after Wheezer, safely but embarrassingly land head first in a deep pool of mud. Wheezer, an the other hand, catches his suspenders on a post and is retrieved safe, clean, and dry. The Ol’ Gray Hoss is hosted on YouTube by Leeweegie1960, with bridge scene starting at 24:36 HERE.

Just for fun, the 1957 Doris Day movie musical The Pajama Game was also filmed at Hollenbeck, with views looking south toward the 6th Street bridge.

Wrapping up, the narrow north end of the lake once had a much smaller arched bridge, near the bandstand gazebo. This bridge was torn down long ago, and rarely appears in archival photos.

Wrapping up, the narrow north end of the lake once had a much smaller arched bridge, near the bandstand gazebo. This bridge was torn down long ago, and rarely appears in archival photos.

The bridge and the gazebo appear with Roscoe Arbuckle and Mabel Normand during their 1915 comedy Fatty, Mabel and the Law, hosted on YouTube by the Al St. John Official YouTube Channel with the bridge scene starting at 3:20 HERE. The low bridge was likely demolished well before 1924, but the bandstand gazebo, also now demolished, appears in the 1929 film Men ‘O War, above right.

This post provides merely an overview of early silent movies filmed beside the now lost Hollenbeck Park bridges. Now that you know what to look for, you will likely recognize these distinctive bridges in other silent films. Giant institutional buildings such as the Hollenbeck Home For Aged People, and the Santa Fe Coast Lines Hospital, stood across from the park, and appear in the background of other films too.

Check out my latest YouTube video – Caught on Film, How Buster Keaton Made The Cameraman, with a score by Jon Mirsalis. Hidden details throughout the film reveal Buster’s journey, leaving his studio behind, visiting familiar locations, and crossing paths with his friend and mentor Roscoe Arbuckle. Please also check the many other Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, and Harold Lloyd videos posted on my YouTube Channel.

Below, an aerial view looking north at Hollenbeck Park, now hemmed in on the west by the Golden State Freeway.

March 30, 2024

Colleen Moore and Buster Keaton Reveal a “Lost” Hollywood Intersection

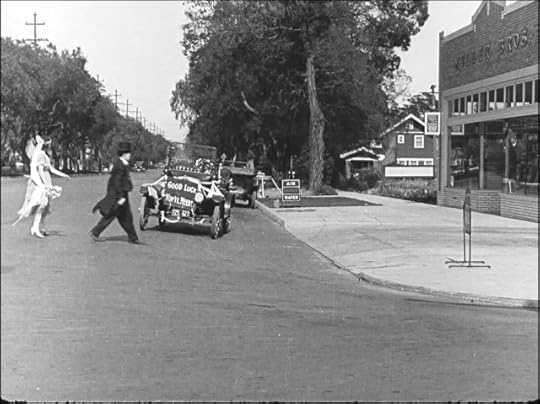

Hollywood was a small, undeveloped community during the early years of cinema. Cahuenga Blvd, now a major thoroughfare, once ran south for two blocks from Hollywood Blvd past Selma to where it ended at Sunset Blvd. Through traffic would then zig-zag, turning left on Sunset and continuing right, south along Townsend, now Ivar, a half block further east. In these early years, and early stages of their careers, future flapper superstar Colleen Moore and stone-faced Buster Keaton filmed matching scenes at the former “T” intersection of Cahuenga and Sunset. As shown below, Stan Laurel filmed an early solo comedy there as well.

Hollywood was a small, undeveloped community during the early years of cinema. Cahuenga Blvd, now a major thoroughfare, once ran south for two blocks from Hollywood Blvd past Selma to where it ended at Sunset Blvd. Through traffic would then zig-zag, turning left on Sunset and continuing right, south along Townsend, now Ivar, a half block further east. In these early years, and early stages of their careers, future flapper superstar Colleen Moore and stone-faced Buster Keaton filmed matching scenes at the former “T” intersection of Cahuenga and Sunset. As shown below, Stan Laurel filmed an early solo comedy there as well.

During A Roman Scandal (1919) leading man Earl Rodney wishes to marry stage-struck Colleen, a wannabe actress who defers his marriage proposal to pursue her thespian dreams. You can view a beautiful scan of the entire film at Joseph Blough’s wonderful YouTube channel.

Out for a stroll, starting at 04:17 HERE, Earl and Colleen notice a publicity billboard (inset) for a live stage production of The Fall of Rome. Notice “MORGAN HARDWARE,” 1503 Cahuenga, at back. Colleen and Earl attend the show, and when the lead actors go on strike, they are hired to replace them.

Out for a stroll, starting at 04:17 HERE, Earl and Colleen notice a publicity billboard (inset) for a live stage production of The Fall of Rome. Notice “MORGAN HARDWARE,” 1503 Cahuenga, at back. Colleen and Earl attend the show, and when the lead actors go on strike, they are hired to replace them.

Above, twin views of Morgan Hardware – a production still from an unidentified comedy, and a modern view with a palm tree standing where “MORGAN” could once be seen.

Above, Stan Laurel (at the corner disguised in a giant dog costume) flees (fleas?) the police in The Pest (1922). You can clearly see the SUNSET BLVD sign and barely make out MORGAN HARDWARE between the ladders.

More views of Morgan Hardware. Above left, during a scene from Day Dreams (1922), presented as if filmed on a cable car in San Francisco, Buster rides east along Sunset looking north past the corner of Cahuenga. The word “HARDWARE” appears left of the cop’s elbow. As explained at 03:04 of my YouTube video about Buster Keaton’s San Francisco Footsteps, Sunset did not have a trolley line, so Buster is filming on a prop trolley being towed close to the south curb, not on a real trolley on tracks moving down the center of the street. That’s why the same-direction auto traffic passes behind Buster during the scene. Above right, an unidentified comedy presented by the Library of Congress Mostly Lost Film Festival, looking SW to Morgan Hardware and the corner of Sunset.

Above, during One Week (1920), newly-wed Buster grabs a policeman’s hat and whistle to rescue his bride from a car driven by his rival. This view to the right also looks SW – notice the matching warehouse air vents in both images.

Above left, impersonating the cop, Buster orders his rival’s car to stop. Above right, Earl and Colleen admire the billboard for the play. Both views look west from the NE corner of Cahuenga toward the Sunset Roofing Company.

Matching views then and now SW along Sunset from Cahuenga, once a “T” intersection. Click to enlarge the One Week frame and you can barely read “The Sunset Roofing Co.” at back.

Click to enlarge – this view looks west down Sunset past Cahuenga, toward the towering Hollywood Athletic Club building on the corner of Schrader at back, and where Earl and Colleen stood on the corner beside the former Hollywood Laundry facility. LAPL.

Click to enlarge – this view looks west down Sunset past Cahuenga, toward the towering Hollywood Athletic Club building on the corner of Schrader at back, and where Earl and Colleen stood on the corner beside the former Hollywood Laundry facility. LAPL.

This closer view shows where the billboard was placed beside the former Hollywood Laundry.

Traveling east along Sunset in Day Dreams, before reaching the corner of Cahuenga above, Buster first passes the circular arched entrance along the side of the building.

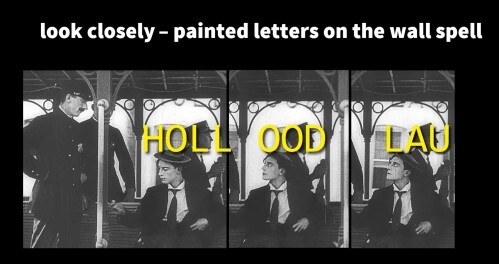

As explained in my book Silent Echoes, and in Buster’s San Francisco Footsteps YouTube video, the initial clues for identifying Buster’s traveling shot were the bottom half of the letters “HOLL” “OOD” “LAU” painted on the background wall. Not surprisingly, San Francisco did not have a Hollywood Laundry, but guess who did!

As explained in my book Silent Echoes, and in Buster’s San Francisco Footsteps YouTube video, the initial clues for identifying Buster’s traveling shot were the bottom half of the letters “HOLL” “OOD” “LAU” painted on the background wall. Not surprisingly, San Francisco did not have a Hollywood Laundry, but guess who did!

Now looking south, here’s an early panoramic view along Sunset forming the back end of the “T” intersection with Cahuenga. The road continues south past the corner of Townsend to the left. Notice the P.F. Pursel & Son Sunset Stable, also appearing below. HollywoodPhotographs.com.

Now looking south, here’s an early panoramic view along Sunset forming the back end of the “T” intersection with Cahuenga. The road continues south past the corner of Townsend to the left. Notice the P.F. Pursel & Son Sunset Stable, also appearing below. HollywoodPhotographs.com.

Above left, a frame from the 1915 (!) Lyons & Moran comedy Pruning The Movies, looking south down Cahuenga toward the “T” intersection at Sunset and P.F. Pursel & Son. Above right, looking east down Sunset with Pursel at center, the 1919 Billie Rhodes comedy A Two-Cylinder Courtship. This 1919 movie also contained scenes that identified matching locales appearing in Keaton’s 1921 shorts The Play House and The Goat – see post Solved! Buster Keaton’s Mystery Colegrove Building.

Then and Now – Buster and his rescued bride Sybil Seely reclaim their car in One Week looking east down Sunset Blvd from the corner of Ivar, a short half-block east from Cahuenga. The Muller Bros. Auto Supplies at 6380 Sunset, pictured on the corner, was ultimately replaced by the Cinerama Dome Theatre.

Click to enlarge – a final view SW at Sunset (red) and the 1500 block of Cahuenga (orange) south of Selma. The image of Buster in The Goat running by the Toribuchi Grocery at 1546 Cahuenga (green), led to one of my all-time favorite discoveries – that at a time when few ethnic Japanese lived anywhere in Los Angeles, the 1500 block was once home to a small, seemingly forgotten Japanese enclave, with stores, lodging, a bath, a school, and a small church. Read all about it here – Silent Hollywood’s Japanese Enclave.

Click to enlarge – a final view SW at Sunset (red) and the 1500 block of Cahuenga (orange) south of Selma. The image of Buster in The Goat running by the Toribuchi Grocery at 1546 Cahuenga (green), led to one of my all-time favorite discoveries – that at a time when few ethnic Japanese lived anywhere in Los Angeles, the 1500 block was once home to a small, seemingly forgotten Japanese enclave, with stores, lodging, a bath, a school, and a small church. Read all about it here – Silent Hollywood’s Japanese Enclave.

As explained in numerous posts, the 1600 block of Cahuenga between Hollywood Blvd and Selma was likely the most widely used filming location in early silent films. Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, Colleen Moore, Stan Laurel, Harry Langdon, Our Gang, Dorothy Devore, Oliver Hardy, and many more filmed there, and it was the favorite block in Hollywood for Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and Harold Lloyd to film. But as seen here, the 1500 block, now with its lost “T” intersection, has its own rich silent film history.

As explained in numerous posts, the 1600 block of Cahuenga between Hollywood Blvd and Selma was likely the most widely used filming location in early silent films. Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, Colleen Moore, Stan Laurel, Harry Langdon, Our Gang, Dorothy Devore, Oliver Hardy, and many more filmed there, and it was the favorite block in Hollywood for Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and Harold Lloyd to film. But as seen here, the 1500 block, now with its lost “T” intersection, has its own rich silent film history.

The San Francisco Silent Film Festival returns April 10-14, this time at the beautiful thousand seat Palace of Fine Arts Theater. Buster Keaton’s Sherlock Jr. (1924) together with One Week fill the prime Saturday evening spot. This YouTube video shows how Buster staged Sherlock Jr. all across Southern California, including new discoveries.

The San Francisco Silent Film Festival returns April 10-14, this time at the beautiful thousand seat Palace of Fine Arts Theater. Buster Keaton’s Sherlock Jr. (1924) together with One Week fill the prime Saturday evening spot. This YouTube video shows how Buster staged Sherlock Jr. all across Southern California, including new discoveries.

Harold Lloyd’s masterpiece The Kid Brother (1928) fills the festival’s family-friendly spot at 12:15 Sunday afternoon. I created a visual essay for the beautiful Criterion Collection Blu-ray release of the film, The Kid Brother Was Close to Home, which you can read about HERE. Both Buster’s and Harold’s films will be accompanied by the magnificent Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra.

Harold Lloyd’s masterpiece The Kid Brother (1928) fills the festival’s family-friendly spot at 12:15 Sunday afternoon. I created a visual essay for the beautiful Criterion Collection Blu-ray release of the film, The Kid Brother Was Close to Home, which you can read about HERE. Both Buster’s and Harold’s films will be accompanied by the magnificent Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra.

Below, the former “T” intersection of Sunset and Cahuenga – spin the image around for a full 360 degree view.

March 2, 2024

Harold Lloyd, Dorothy Devore, Movie Pilot Frank Clarke – Stunt Birds of a Feather

Here’s more Hollywood history appearing in another little-known film, this time from a Columbia Studios Screen Snapshots newsreel.

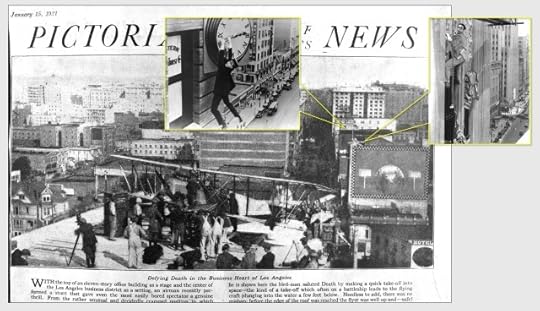

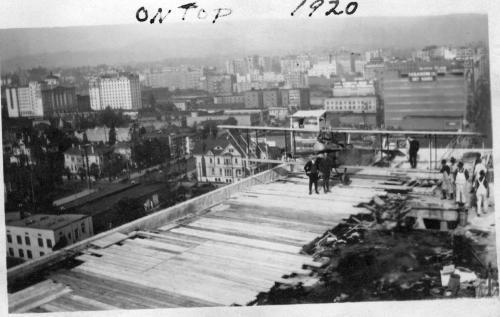

Above, Screen Snapshots captured pioneer Hollywood stunt pilot/actor Frank Clarke flying an airplane from the roof of the Los Angeles Railroad Building downtown, beginning at 01:35 on YouTube HERE. Seen here under construction, before a later building would block the full view, it still stands at 1060 S Broadway at the NE corner of Broadway and 11th.

Looking north up Broadway, if the Blackstone Building at back seems familiar, it’s because it appears behind Harold Lloyd during Safety Last! – 1923, still standing at Broadway and 9th.

Here are matching views from the movie, left, and one of many images of Frank Clarke available through the San Diego Air & Space Museum archival Flickr account. You can read part of the “BLACKSTONE” building sign in both images.

A news account of Frank’s stunt. At back, to the right, stand 950 and 908 S Broadway, the buildings where Harold would build rooftop sets for his climbing stunts in Feet First – 1930 and Safety Last!

For visual context, here’s a side view of where Frank flew from the roof of the Railway Building (unfinished at the time), near the three-story triangular building, now lost, at the former intersection of Broadway and Broadway Place, where Harold built sets for his initial climbing scenes from Safety Last! (left) and Feet First (middle). USC Digital Library.

Using Frank’s photo for reference, we see up the street the 950 and 908 S Broadway rooftops where Harold would later build stunt sets for the next stage of his climb in Safety Last! and Feet First.

Using Frank’s photo for reference, we see up the street the 950 and 908 S Broadway rooftops where Harold would later build stunt sets for the next stage of his climb in Safety Last! and Feet First.

Dorothy Devore made stunt comedies matching Harold’s skill and production techniques. Above, a frame from Hold Your Breath – 1924, notice the Blackstone Building behind her. Dorothy screen captures courtesy the Retroformat Vault – https://www.patreon.com/retroformatsilents.

Dorothy Devore made stunt comedies matching Harold’s skill and production techniques. Above, a frame from Hold Your Breath – 1924, notice the Blackstone Building behind her. Dorothy screen captures courtesy the Retroformat Vault – https://www.patreon.com/retroformatsilents.

Above, looking again at the Railway Building paired with a promotional still from Hold Your Breath. Dorothy appears to be at great height, but she is in fact hanging on from the side of the one-story rooftop building far away from the main edge of the roof. Historian Richard W. Bann pointed out that when Harold works at the De Vore Department Store during Safety Last! (right) he is paying indirect tribute to Dorothy.

Above, looking again at the Railway Building paired with a promotional still from Hold Your Breath. Dorothy appears to be at great height, but she is in fact hanging on from the side of the one-story rooftop building far away from the main edge of the roof. Historian Richard W. Bann pointed out that when Harold works at the De Vore Department Store during Safety Last! (right) he is paying indirect tribute to Dorothy.

Dorothy filmed earlier stunts atop the roof of 908 S Broadway, the same rooftop where Harold filmed the clock scenes from Safety Last! The facade of Harold’s set faced away from the street, while Dorothy’s facade faced toward the street. The large white building at back is the Hamburger’s Department Store still standing at Broadway and 8th.

This building facade and safety net were built for another movie filmed years later atop the LA Railway Building (several late-1920s buildings, including LA City Hall, appear at back), but this simulated composite view shows how Dorothy safely filmed her stunt climbing scenes here. Marc Wanamaker – Bison Archives.

This building facade and safety net were built for another movie filmed years later atop the LA Railway Building (several late-1920s buildings, including LA City Hall, appear at back), but this simulated composite view shows how Dorothy safely filmed her stunt climbing scenes here. Marc Wanamaker – Bison Archives.

Above, photos by George Watson from the Delmar Watson Archives. Frank took flight with little clearance to spare.

Above, looking north up Broadway at Frank’s lift-off – the completed Railway Building now boasts a prominent “Western Auto Supply Co” sign. The Blackstone Building appears at back. USC Digital Library.

Above, a final view of Frank’s launch pad, before the one-story rooftop building Dorothy climbed on (above) was constructed. San Diego Air & Space Museum archival Flickr account.

Above, a final view of Frank’s launch pad, before the one-story rooftop building Dorothy climbed on (above) was constructed. San Diego Air & Space Museum archival Flickr account.

I knew nothing about Frank Clark (later Clarke) before starting this post. He led quite a life, born in 1898, he was one of the original Hollywood stunt pilots, transferring between moving airplanes, landing a plane atop a moving train, and doubling for actors such as James Cagney. The 6′ 2″ actor is credited with over a dozen roles and stunts on . Frank served as a major in the Air Force during WWII, training young pilots.

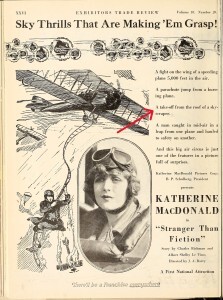

I knew nothing about Frank Clark (later Clarke) before starting this post. He led quite a life, born in 1898, he was one of the original Hollywood stunt pilots, transferring between moving airplanes, landing a plane atop a moving train, and doubling for actors such as James Cagney. The 6′ 2″ actor is credited with over a dozen roles and stunts on . Frank served as a major in the Air Force during WWII, training young pilots.  Biographer and LA Times staff writer Cecilia Rasmussen explains Frank died in 1948 when a practical joke went wrong. He had planned to dive bomb a friend’s rural cabin with bags of cow manure, but during the steep descent the bags became lodged behind the control stick, causing his plane to crash. Cecilia reports Frank’s rooftop stunt discussed here was filmed for the Katherine MacDonald Pictures Corp. movie titled It Could Happen, released in 1921 as Stranger Than Fiction. Publicity for the film boasts about “A take-off from the roof of a skyscraper.”

Biographer and LA Times staff writer Cecilia Rasmussen explains Frank died in 1948 when a practical joke went wrong. He had planned to dive bomb a friend’s rural cabin with bags of cow manure, but during the steep descent the bags became lodged behind the control stick, causing his plane to crash. Cecilia reports Frank’s rooftop stunt discussed here was filmed for the Katherine MacDonald Pictures Corp. movie titled It Could Happen, released in 1921 as Stranger Than Fiction. Publicity for the film boasts about “A take-off from the roof of a skyscraper.”

I hope you will check out Buster Keaton’s San Francisco footsteps, a true window into the past. Please also check the many other Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, and Harold Lloyd videos posted on my YouTube Channel, including How Harold Filmed Safety Last!

Below, the LA Railway Building at Broadway and 11th.

February 4, 2024

Historic Hollywood Relics Found In “Lost” Films

This post presents bits and pieces of Hollywood history appearing in an assortment of little-known films, many unavailable for decades.

I closely follow Dave Glass’s invaluable YouTube channel. You never know what brief scene from an obscure film will reveal more Hollywood history. To begin, check out these scenes from the 1924 Billy Bevan comedy Bright Lights, starting at 05:25 HERE and again at 06:05 HERE. Do they look familiar?

That’s right – it’s the back end of the Chaplin-Keaton-Lloyd Alley, where Harold Lloyd filmed many scenes from Safety Last! (1923). Check out my YouTube videos showing the discovery of the alley HERE, and how Harold made Safety Last! HERE.

Next, a recent post showed how Douglas Fairbanks and Buster Keaton filmed along all sides of the former Hollywood Fire-Police Station, leading a virtual tour around the now lost site, read more HERE. It was fun to show in this post how the adorable early silent film comedienne Gale Henry frequently filmed here too.

Next, a recent post showed how Douglas Fairbanks and Buster Keaton filmed along all sides of the former Hollywood Fire-Police Station, leading a virtual tour around the now lost site, read more HERE. It was fun to show in this post how the adorable early silent film comedienne Gale Henry frequently filmed here too.

Well, thanks to Joseph Blough’s wonderful YouTube channel, we see more views of Gale Henry filming in back of the fire station during her 1919 film Pants – watch video HERE. A key plot device, a seemingly insurmountable brick wall separates a “boy’s college” from a “girl’s seminary,” leading to mischief, mayhem, and true love. Above, it’s love at first sight as the college handy-man encounters Gale, the seminary cook.

A wider view during Pants, left, reveals the free-standing wooden car parking enclosure behind the wall, fully visible to the right during a brief clip of the Sid Smith and Harry McCoy Hallroom Boys comedy Put and Take (1921), right, hosted by the Eye Filmmuseum at their Bits & Pieces YouTube channel series, Nr. 631, visible at 01:35 HERE.

Gale’s brick wall appears throughout the Douglas Fairbanks 1916 comedy Flirting With Fate, above left, looking south, above right looking NW (click to enlarge), the arrow marking Doug’s pathway relative to Gale and the wooden car parking enclosure in the corner. HollywoodPhotographs.com.

Next, responding to growing, widely criticized Hollywood scandals, the film community produced self-promotional movies reassuring middle America that the folks in Hollywood were, gosh darn it, just good, honest, friendly folks like everyone else. One of my favorite posts dissects such a film, Hollywood Snapshots, in great detail, and its treasure trove of historic, often unique images of early Hollywood. From that film, above, rare street level views in 1922, of the 7200 Santa Monica Blvd. entrance to the Pickford Fairbanks Studio (left – note Doug’s castle set for Robin Hood) and the 1520 Vine St. entrance to the Famous-Players Lasky Studios (right). Can you imagine just walking along the street and seeing a castle?

Once again with gratitude to Joseph Blough, we can study another visually stunning historic 1922 self-promotional film Night Life in Hollywood. I hope to do a lengthy detailed post about this film, which features views of the Will Rogers’ early home in Beverly Hills, the Hollywood homes of Jack Kerrigan, Wallace Reid, and Theo Roberts, and numerous Hollywood Blvd. locales, including the once open fields further west of town. Until then, above, country boy Joe Frank Glendon decides to check out Hollywood for himself, where his new friend leads him into the 6642 Santa Monica Blvd. entrance to the Hollywood Metropolitan Studios – click to enlarge. HollywoodPhotographs.com.

Above, following her brother Joe to town, and convinced her alluring cinematic charms must be shared with the world, country gal Gale Henry (yes, her again, another fun performance), attempts to sneak into the studio for an audition. The arrow above marks her position by the front office. At left, Gale grabs a taxi beside the lost Southern Pacific depot – the homes at back once stood on Central Ave. across the street. The Hollywood Metropolitan Studios shown above, completely reconfigured but still operating at the same locale today as the Sunset Las Palmas Studios, is where Harold Lloyd would later create his independently produced films after leaving the Hal Roach Studios.

Above, following her brother Joe to town, and convinced her alluring cinematic charms must be shared with the world, country gal Gale Henry (yes, her again, another fun performance), attempts to sneak into the studio for an audition. The arrow above marks her position by the front office. At left, Gale grabs a taxi beside the lost Southern Pacific depot – the homes at back once stood on Central Ave. across the street. The Hollywood Metropolitan Studios shown above, completely reconfigured but still operating at the same locale today as the Sunset Las Palmas Studios, is where Harold Lloyd would later create his independently produced films after leaving the Hal Roach Studios.

Once again from Night Life in Hollywood, noted Japanese actor Sessue Hayakawa and his wife Tsuro Aoki greet country boy Joe and his friend at their home once located at 1904 Argyle on the NE corner of Franklin. It is here in the movie Joe realizes “the fact that the Hollywood motion picture colony is no sensual Babylon that the home town papers painted it.” Known as Castle Glengarry, the incredible mansion was built by Hollywood promoter Dr. Schloesser (Dr. Castles), whose next, bigger, larger mansion just up the street, Castle Sans Souci, appeared in many early films, including Charlie Chaplin’s Tillie’s Punctured Romance (1914). Read my post about Castle Sans Souci HERE. USC Digital Library.

Once again from Night Life in Hollywood, noted Japanese actor Sessue Hayakawa and his wife Tsuro Aoki greet country boy Joe and his friend at their home once located at 1904 Argyle on the NE corner of Franklin. It is here in the movie Joe realizes “the fact that the Hollywood motion picture colony is no sensual Babylon that the home town papers painted it.” Known as Castle Glengarry, the incredible mansion was built by Hollywood promoter Dr. Schloesser (Dr. Castles), whose next, bigger, larger mansion just up the street, Castle Sans Souci, appeared in many early films, including Charlie Chaplin’s Tillie’s Punctured Romance (1914). Read my post about Castle Sans Souci HERE. USC Digital Library.

Above, a view of the rear of the house, a point of view of this once landmark home that may be truly unique, as I have never seen the back of this lost home in a photo before. Also, how cute is that? Sessue and Tsuro’s pet dog had his own Castle Glengarry dog house!

I have identified dozens of random locations from dozens of random obscure films that don’t easily fit within a certain theme or category, so I hope to post more “potpourri” articles such as this to help document Hollywood’s vast unclaimed visual history. Remember too, the remarkable street level views of early Hollywood reported in this post, many of which are unique, were captured from the films presented on YouTube for our enjoyment and study by Hollywood heroes Dave Glass and Joseph Blough. Please visit their YouTube channels – Dave Glass YouTube – Joseph Blough YouTube.

I hope you will check out my latest YouTube video Buster Keaton’s San Francisco footsteps, and the many other Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, and Harold Lloyd videos posted on my YouTube Channel.

January 19, 2024

Solved! – Buster Keaton’s 100 Year Old Three Ages Bungalow

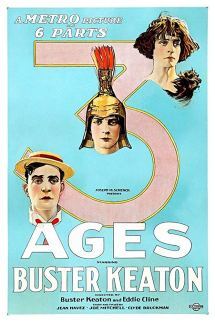

Love triumphs over all. Buster Keaton’s first feature comedy Three Ages (1923) tells three tales of love, set in the Stone Age, the Roman Age, and the Present Age (i.e. 1923), where against all odds underdog Buster wins the girl played by Margaret Leahy by defeating villainous Wallace Beery.

The movie ends with brief postscript finales – caveman Buster and wife, and their 10 caveman kids exit their cave one-by-one. Next, elegant Roman Age Buster and wife and 5 children, all wearing graceful togas, exit their formal columned home. For the final shot in the movie, Present Age Buster and wife exit their Hollywood bungalow, along with … one tiny dog! What a perfect, purely visual joke to end the film.

The movie ends with brief postscript finales – caveman Buster and wife, and their 10 caveman kids exit their cave one-by-one. Next, elegant Roman Age Buster and wife and 5 children, all wearing graceful togas, exit their formal columned home. For the final shot in the movie, Present Age Buster and wife exit their Hollywood bungalow, along with … one tiny dog! What a perfect, purely visual joke to end the film.

The Roman home was a backlot set, and as reported years ago in my book Silent Echoes, the domestic cave was filmed at the Iverson Ranch (details below). But I’ve sought out the Present Age bungalows for over 25 years. Then once again, suddenly, a clue from another silent film revealed this location, and more remarkably, the home is still standing unchanged. Below, does this view look familiar?

The Roman home was a backlot set, and as reported years ago in my book Silent Echoes, the domestic cave was filmed at the Iverson Ranch (details below). But I’ve sought out the Present Age bungalows for over 25 years. Then once again, suddenly, a clue from another silent film revealed this location, and more remarkably, the home is still standing unchanged. Below, does this view look familiar?

I closely follow Joseph Blough’s wonderful YouTube channel, as he regularly posts rare and seldom seen silent and classic-era films, often sourced from the Library of Congress Archives. Joseph posted a beautifully clear 7-minute fragment from a Buster Brown silent comedy short Buster’s Bustup (1925), starring Arthur Trimble as Buster and Pete the Dog as Tige. Sitting on a steel girder at a construction site, Buster and Pete find themselves rising high up in the air. Buster and Pete remain relatively calm and nimble, so the fun is in watching them cleverly overcome their obstacles, rather than trembling in fear, while getting the best of a cranky construction foreman.

I closely follow Joseph Blough’s wonderful YouTube channel, as he regularly posts rare and seldom seen silent and classic-era films, often sourced from the Library of Congress Archives. Joseph posted a beautifully clear 7-minute fragment from a Buster Brown silent comedy short Buster’s Bustup (1925), starring Arthur Trimble as Buster and Pete the Dog as Tige. Sitting on a steel girder at a construction site, Buster and Pete find themselves rising high up in the air. Buster and Pete remain relatively calm and nimble, so the fun is in watching them cleverly overcome their obstacles, rather than trembling in fear, while getting the best of a cranky construction foreman.

Click to enlarge – as Buster and Pete rise in the air, at 2:19 the first point of view shot looking down clearly matches Buster’s Three Ages bungalow! Buster’s doorway is the sunlit doorway closest to the corner.

Click to enlarge – as Buster and Pete rise in the air, at 2:19 the first point of view shot looking down clearly matches Buster’s Three Ages bungalow! Buster’s doorway is the sunlit doorway closest to the corner.

Click to enlarge – studying the Buster Brown frame revealed the landmark St. George Court Apartments in the background (above), still standing to the south at 1245 Vine Street. USC Digital Library.

Click to enlarge – studying the Buster Brown frame revealed the landmark St. George Court Apartments in the background (above), still standing to the south at 1245 Vine Street. USC Digital Library.

Click to enlarge – other views revealed the Taft Building to the north at Hollywood and Vine. Triangulating from these north and south landmarks, I quickly fixed the SW corner of El Centro and Leland as Buster’s home location. HollywoodPhotographs.com.

Click to enlarge – other views revealed the Taft Building to the north at Hollywood and Vine. Triangulating from these north and south landmarks, I quickly fixed the SW corner of El Centro and Leland as Buster’s home location. HollywoodPhotographs.com.

More remarkable, whereas many/most little Hollywood homes have been replaced by giant modern apartment blocks, Buster’s bungalow is still there! The arrow marks Buster’s path from his front entrance at 1425 El Centro. The tiny palm trees planted in the wide sidewalk median visible during the scene are now perhaps 100 feet tall.

More remarkable, whereas many/most little Hollywood homes have been replaced by giant modern apartment blocks, Buster’s bungalow is still there! The arrow marks Buster’s path from his front entrance at 1425 El Centro. The tiny palm trees planted in the wide sidewalk median visible during the scene are now perhaps 100 feet tall.

Click to enlarge – these matching views looking SW show the corner of El Centro and Leland in the foreground stands only a few blocks from Buster’s former studio at Lillian Way and Eleanor (yellow oval) above. The storage building clock tower still stands on the corner of Santa Monica Blvd. and Cahuenga. The storage building was featured in two recent posts, how Buster and W.C. Fields crossed paths filming near Buster’s studio (HERE), and how Stan Laurel also crossed paths with W.C. Fields near Buster’s studio (HERE). The Greek-style building to the left of the curve in both images was the former Hollywood Methodist Episcopal Church, once standing at 1201 Vine at the corner of Lexington. The aerial view above was taken in 1924, before St. George Court was built up the street from the church. HollywoodPhotographs.com.

Click to enlarge – these matching views looking SW show the corner of El Centro and Leland in the foreground stands only a few blocks from Buster’s former studio at Lillian Way and Eleanor (yellow oval) above. The storage building clock tower still stands on the corner of Santa Monica Blvd. and Cahuenga. The storage building was featured in two recent posts, how Buster and W.C. Fields crossed paths filming near Buster’s studio (HERE), and how Stan Laurel also crossed paths with W.C. Fields near Buster’s studio (HERE). The Greek-style building to the left of the curve in both images was the former Hollywood Methodist Episcopal Church, once standing at 1201 Vine at the corner of Lexington. The aerial view above was taken in 1924, before St. George Court was built up the street from the church. HollywoodPhotographs.com.

Another fun discovery – Buster in 3D! Different Blu-ray releases of Three Ages are presented from either the A or B camera negative. (Silent movies were commonly filmed with two cameras placed side-by-side. The A camera negative would generate prints for American theaters, while the B camera negative would be sent to Europe to create prints locally.) The parallax offset between two adjacently photographed images creates a 3D effect. It may not be easy, but if you can focus looking forward, beyond these twin images, and cross your eyes a bit, the right image as seen by your left eye will overlap with the left image as seen by your right eye, yielding a 3D image in the center.

Another fun discovery – Buster in 3D! Different Blu-ray releases of Three Ages are presented from either the A or B camera negative. (Silent movies were commonly filmed with two cameras placed side-by-side. The A camera negative would generate prints for American theaters, while the B camera negative would be sent to Europe to create prints locally.) The parallax offset between two adjacently photographed images creates a 3D effect. It may not be easy, but if you can focus looking forward, beyond these twin images, and cross your eyes a bit, the right image as seen by your left eye will overlap with the left image as seen by your right eye, yielding a 3D image in the center.

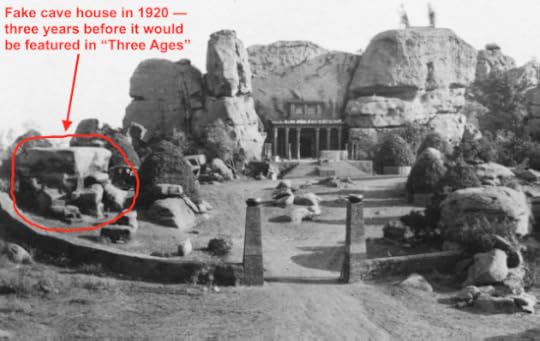

Switching gears, Keaton filmed the Stone Age scenes at the Iverson Movie Ranch in Chatsworth, about 25 miles north of Hollywood, beside the unusual rock formations called the Garden of the Gods. I cover more than a dozen caveman scenes in my book. Above, just for fun, here’s 25 year old photo of me sitting beside Buster’s Stone Age bathtub, along with a shot from the 1926 Fox film Silver Treasure. The two prominent rocks at back, perhaps the most famous in the Garden of the Gods, are called the Tower Rock at left, and The Sphinx at right. As reported by Hollywood and Chatsworth film historian and “Iverson Movie Ranch Blog” host Dennis, these landmark rocks and other spots at the Iverson appear in the earliest days of film, and in hundreds of major Hollywood productions, “B” westerns, and television shows, and is still used even today. Here’s the link to his phenomenal, vast, and extensively researched Iverson Movie Ranch Blog.

Buster’s closing scene was filmed beyond the south end of what is now the community pool for the Indian Hills Mobile Home Village near the Iverson Movie Ranch. The giant cleft rock is obscured by trees. While I report this spot in my book, I have never visited the site in person, and Dennis patiently explained to me precisely where Buster’s now relatively inaccessible setting was located.

Buster’s closing scene was filmed beyond the south end of what is now the community pool for the Indian Hills Mobile Home Village near the Iverson Movie Ranch. The giant cleft rock is obscured by trees. While I report this spot in my book, I have never visited the site in person, and Dennis patiently explained to me precisely where Buster’s now relatively inaccessible setting was located.

With a color photo and common details provided by Dennis, a closer view of the back corner of the community pool shows the entrance to Buster’s “cave” was actually an open space between these two rocks.

With a color photo and common details provided by Dennis, a closer view of the back corner of the community pool shows the entrance to Buster’s “cave” was actually an open space between these two rocks.

Of particular interest, one of Dennis’s posts explains the fake rock house Buster used in Three Ages appeared in earlier films! Here it is, to the left of Tower Rock and The Sphinx. Read more HERE. Dennis also writes about Buster filming The Paleface at the Iverson HERE, and filming an episode of the television show Route 66 HERE.

Of particular interest, one of Dennis’s posts explains the fake rock house Buster used in Three Ages appeared in earlier films! Here it is, to the left of Tower Rock and The Sphinx. Read more HERE. Dennis also writes about Buster filming The Paleface at the Iverson HERE, and filming an episode of the television show Route 66 HERE.

For a great overview of Dennis’s incredible work, and to see for yourself how the Garden of the Gods appeared not only in Three Ages, but in Man-Woman-Marriage (1921), Richard the Lion Hearted (1923), and Tell It To The Marines (1926), download his amazing 43 page PDF program hosted by the Chatsworth Historical Society.

For a great overview of Dennis’s incredible work, and to see for yourself how the Garden of the Gods appeared not only in Three Ages, but in Man-Woman-Marriage (1921), Richard the Lion Hearted (1923), and Tell It To The Marines (1926), download his amazing 43 page PDF program hosted by the Chatsworth Historical Society.

Dennis also wanted to share the earliest known filming at the Iverson was the 1913 lost film Everyman, starring Linda Arvidson (estranged wife at the time of D.W. Griffith), read his post HERE, while his post HERE about the 1917 William S. Hart Western The Silent Man mentions other lost silent movies and filming at the Iverson Ranch by Thomas Ince.

Remember, Dennis also covers classic-era films, “B” westerns, and vintage to present-day television appearances filmed at the Iverson – the early silent era is but one field of many covered at his blog http://iversonmovieranch.blogspot.com/.

In closing, Dennis and I owe a huge debt of gratitude to Ben Burtt, one of the premiere Iverson historians, for introducing us to this hallowed filming location. It was Ben who first discovered nearly all of the Three Ages rock locations, including the bathtub rock. The multi-talented writer, director, editor, and film-maker is perhaps best known as the 4-time Academy Award-winning sound designer and editor for such films as Stars Wars, ET, and Indiana Jones.

In closing, Dennis and I owe a huge debt of gratitude to Ben Burtt, one of the premiere Iverson historians, for introducing us to this hallowed filming location. It was Ben who first discovered nearly all of the Three Ages rock locations, including the bathtub rock. The multi-talented writer, director, editor, and film-maker is perhaps best known as the 4-time Academy Award-winning sound designer and editor for such films as Stars Wars, ET, and Indiana Jones.

The recent Eureka Entertainment Blu-ray release of Three Ages includes the video essay about Three Ages I prepared for Kino-Lorber a few years ago. The essay includes later discoveries not reported in my book.

Below, Buster’s bungalow at 1425 El Centro in Hollywood. Look at those towering palm trees!

December 30, 2023

Buster Keaton’s San Francisco footsteps

Buster filmed scenes from Day Dreams (1922) and The Navigator (1924) across San Francisco. Most locations look remarkably unchanged a century later. My latest YouTube video reveals every SF locale with then and now views, intercut with scenes where sneaky Buster actually filmed in Hollywood and Oakland instead.

The video quickly identifies every scene (as does this printed PDF tour you can download), and highlights a fun fact – Buster filmed near three famous SF landmarks BEFORE they were built. This post highlights these “prenatal” landmarks by diving deep into vintage aerial photos.

Click to enlarge – to begin, this 1922 aerial photo of the SF North Beach neighborhood reveals four Day Dream scenes; filmed looking west from Lombard at Taylor (red), looking east from Bay at Taylor (orange), east from Lombard at Columbus (yellow), and south from Lombard at Columbus (green). Notice how Buster filmed efficiently on flat streets relatively close together. David Rumsey Map Collection.

Click to enlarge – to begin, this 1922 aerial photo of the SF North Beach neighborhood reveals four Day Dream scenes; filmed looking west from Lombard at Taylor (red), looking east from Bay at Taylor (orange), east from Lombard at Columbus (yellow), and south from Lombard at Columbus (green). Notice how Buster filmed efficiently on flat streets relatively close together. David Rumsey Map Collection.

Three SF landmarks, the Lombard Street hairpin turns, Coit Tower, and Saints Peter and Paul Church on Washington Square, are absent in the above image. They would have appeared in the background of Buster’s scenes, but they hadn’t been built yet! The images below shows their future locations. OpenSFHistory.org – Lombard – Coit Tower – Saints Peter and Paul.

Three SF landmarks, the Lombard Street hairpin turns, Coit Tower, and Saints Peter and Paul Church on Washington Square, are absent in the above image. They would have appeared in the background of Buster’s scenes, but they hadn’t been built yet! The images below shows their future locations. OpenSFHistory.org – Lombard – Coit Tower – Saints Peter and Paul.

Click to enlarge, the same circa 1922 photo as above, shows the future sites of the three SF landmarks Buster missed because they weren’t built yet. The red and yellow patches in the movie frames above show where the landmarks would have appeared in Buster’s scenes. The church’s missing appearance is explained further below.

Click to enlarge, the same circa 1922 photo as above, shows the future sites of the three SF landmarks Buster missed because they weren’t built yet. The red and yellow patches in the movie frames above show where the landmarks would have appeared in Buster’s scenes. The church’s missing appearance is explained further below.

A closer view west up Lombard from Taylor, the first silent movie location I ever discovered, back in 1996. The block farthest up the hill would later become famous as “the crookedest street in the world.” Construction plans for the eight hairpin turns were approved June 9, 1922, around the time Buster filmed. The brick street was quickly torn up, but work halted all summer awaiting one homeowner’s approval. The nearly completed construction photo is dated December 14, 1922, so Buster missed capturing this future landmark by only a few months. On the other hand, Buster was ten years too soon for Coit Tower. The landmark honoring the City’s firefighters was built in 1932-1933. OpenSFHistory.org.

Later in the film, further south, Buster rides a cable car turning the corner from Washington onto Powell, blissfully unaware of the cops who reverse course to chase after him. Looking north, the setting is nearly unchanged, except today for the twin spires of Saints Peter and Paul Church now appearing at back. This beautiful church, facing Washington Square nearby (see aerial view above), played a major role in Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments (1923), where it appears under construction (left). Once again Buster was too soon.

Later in the film, further south, Buster rides a cable car turning the corner from Washington onto Powell, blissfully unaware of the cops who reverse course to chase after him. Looking north, the setting is nearly unchanged, except today for the twin spires of Saints Peter and Paul Church now appearing at back. This beautiful church, facing Washington Square nearby (see aerial view above), played a major role in Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments (1923), where it appears under construction (left). Once again Buster was too soon.

Vertigo – Day Dreams, same NE corner of Washington and Powell. Keaton (oval) sits in the cable car.

There’s more. Buster’s Day Dreams intersects with Alfred Hitchcock’s masterpiece Vertigo (1958). When Scottie (James Stewart) traces Madeleine (Kim Novak) by car back to his own apartment, they cross paths twice with Buster. Note matching window (red box). Read more HERE.

Matching views from Day Dreams and Bullitt.

Buster and ‘King of Cool’ actor Steve McQueen also crossed paths filming stunts. McQueen’s celebrated car chase in Bullitt (1968) matched views from Day Dreams looking SE down Columbus Avenue, with the same prominent apartment block at Mason and Greenwich at back. Read more HERE.

Click to enlarge – more views from Day Dreams, Washington at Powell, view north red, view west orange, and Second at Minna, view east green and view west yellow. David Rumsey Map Collection.

Click to enlarge – more views from Day Dreams, Washington at Powell, view north red, view west orange, and Second at Minna, view east green and view west yellow. David Rumsey Map Collection.

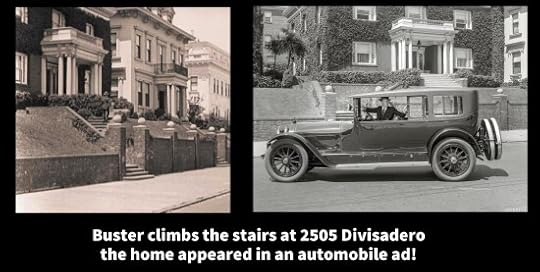

In closing, a scene above from The Navigator staged at 2505 Divisadero.

In closing, a scene above from The Navigator staged at 2505 Divisadero.

I hope you will check out Buster Keaton’s San Francisco footsteps, a true window into the past. It also contains many Day Dreams scenes filmed in Oakland and in Hollywood, as well as scenes from The Navigator. Please also check the many other Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, and Harold Lloyd videos posted on my YouTube Channel.

Below, Lombard at Taylor on Google Maps.

December 16, 2023

Stan Laurel and W.C. Fields Crossed Paths Near the Keaton and Metro Studios

Expanding on the previous post, Stan Laurel also crossed paths with W.C. Fields, at the Metro Studios south of Buster Keaton’s studio, with the same landmark storage building still standing appearing at back. The scenes further below appear in Stan’s 1925 film Twins, made with producer Joe Rock after Stan was dropped by the Hal Roach Studio as a solo performer.

The same storage building appears in The Balloonatic, Twins, and If I Had A Million

Stan’s lesser known film Twins was kindly brought to my attention by Dave Heath, who runs the vast and wonderfully encyclopedic Hal Roach Studio films blog Another Nice Mess. Comedy mayhem ensues when husband Stan leaves town on business the same time his identical twin brother bachelor Stan arrives unannounced, confounding husband Stan’s unaware wife when bachelor Stan begins dating her best friend.

Stan filmed a scene bumping into an actor portraying his twin, knocking each other down, beside a former Metro Studios property storage building on the NW corner of Cahuenga and Willoughby a block south of Keaton’s studio.

Click to enlarge – the same Metro Studio corner, looking to the NW at left, and to the SE at right, with Buster’s studio in the foreground for reference. HollywoodPhotographs.com

Click to enlarge – the same Metro Studio corner, looking to the NW at left, and to the SE at right, with Buster’s studio in the foreground for reference. HollywoodPhotographs.com

Click to enlarge – a closer view of the same corner of Cahuenga at Willoughby.

Click to enlarge – a closer view of the same corner of Cahuenga at Willoughby.

Click to enlarge – again, closer views of Cahuenga and Willoughby, now both looking to the NW. HollywoodPhotographs.com

Click to enlarge – again, closer views of Cahuenga and Willoughby, now both looking to the NW. HollywoodPhotographs.com

Click to enlarge – here one of the angry women chases husband Stan or bachelor Stan (I forget which) up Cahuenga from Willoughby past the property storage buildings and scene docks on the Metro Studio lot. Notice also that some type of underground pipe or trench is being installed along Cahuenga.

Click to enlarge – here one of the angry women chases husband Stan or bachelor Stan (I forget which) up Cahuenga from Willoughby past the property storage buildings and scene docks on the Metro Studio lot. Notice also that some type of underground pipe or trench is being installed along Cahuenga.

Remarkably, Stan and W.C. Fields filmed at the same NW corner of Cahuenga and Willoughby, creating a continuous panoramic view of its corner cement curb. The Metro building appearing with Stan in 1925 was completely demolished when Bill filmed a scene from If I Had A Million here in 1932, just seven years later. You can read many more details and locations about Bill’s film in the prior post HERE.

Remarkably, Stan and W.C. Fields filmed at the same NW corner of Cahuenga and Willoughby, creating a continuous panoramic view of its corner cement curb. The Metro building appearing with Stan in 1925 was completely demolished when Bill filmed a scene from If I Had A Million here in 1932, just seven years later. You can read many more details and locations about Bill’s film in the prior post HERE.

A closing shot, the same six-story storage facility, built in 1922, still standing at 6372 Santa Monica Blvd. on the SE corner of Cahuenga, appears two blocks up the street behind Stan and W.C. As I explain in the prior post, the building was expanded around 1925, now twice as large, but obviously the work was completed after Stan had filmed Twins.

A closing shot, the same six-story storage facility, built in 1922, still standing at 6372 Santa Monica Blvd. on the SE corner of Cahuenga, appears two blocks up the street behind Stan and W.C. As I explain in the prior post, the building was expanded around 1925, now twice as large, but obviously the work was completed after Stan had filmed Twins.

Please check out my YouTube channel, including new visual discoveries showing how Buster Keaton made The General. I wrote its musical score, the Paddlewheel Rag, back in 1975, and employed the Musescore app to record it for the video.

Google Maps view of Willoughby at Cahuenga today.

November 11, 2023

Keaton and W.C. Fields Cross Paths Again Near Buster’s Studio

Buster Keaton filmed The Chemist (1936) and W.C. Fields filmed Running Wild (1927) beside the same apartment building still standing across the street from the Astoria studios where both movies were made in Queens, New York. (Links to detailed posts HERE and HERE).

Click to enlarge – Keaton – The Chemist and Fields – Running Wild beside the SW corner of 35th Ave. and 35th St. in Queens. The Astoria studios where they both worked stands across the street.

Yet another landmark building, still standing in Hollywood, also appears in their films. Further, these movies shed light on the history of the Keaton Studio itself.

A scene from The Balloonatic (1923) filmed due east of the Keaton Studio (above) reveals a six-story storage facility, built in 1922, standing at 6372 Santa Monica Blvd. on the SE corner of Cahuenga. Notice the extant clock tower – click to enlarge. The building is larger in the color view because a six-story expansion was added in 1924. Looking north from Romaine east of Lillian Way, this scene also reveals the Keaton Studio dressing room windows, and the back of the studio sign (see front of sign inset).

A scene from The Balloonatic (1923) filmed due east of the Keaton Studio (above) reveals a six-story storage facility, built in 1922, standing at 6372 Santa Monica Blvd. on the SE corner of Cahuenga. Notice the extant clock tower – click to enlarge. The building is larger in the color view because a six-story expansion was added in 1924. Looking north from Romaine east of Lillian Way, this scene also reveals the Keaton Studio dressing room windows, and the back of the studio sign (see front of sign inset).

The fully expanded warehouse appears next during a scene in Keaton’s 1925 feature Go West as firemen prepare to hose down a cattle stampede running amok on city streets. The view looks east down Santa Monica Blvd. In the movie frame you can read most of the Cahuenga street sign and part of the facility’s “Hollywood 3569” phone number.

Jumping now to W.C. Fields, the 1932 anthology film If I Had A Million (now on Blu-ray) depicts how people’s lives change when a stranger gifts them $1M out of the blue. Some stories are comedic, some uplifting, and some tragic. For comedy Fields and his partner Alison Skipworth use the money to take revenge on road hogs. They purchase a fleet of cheap used cars, and hire a team of drivers to follow with them driving in formation. Whenever some road hog cuts Bill off, Bill runs the offender off the road, ruining both of their cars. Bill then hops into the next car in their fleet, vigilant for the next road hog victim. Bill and Allison spend a perfect day

Jumping now to W.C. Fields, the 1932 anthology film If I Had A Million (now on Blu-ray) depicts how people’s lives change when a stranger gifts them $1M out of the blue. Some stories are comedic, some uplifting, and some tragic. For comedy Fields and his partner Alison Skipworth use the money to take revenge on road hogs. They purchase a fleet of cheap used cars, and hire a team of drivers to follow with them driving in formation. Whenever some road hog cuts Bill off, Bill runs the offender off the road, ruining both of their cars. Bill then hops into the next car in their fleet, vigilant for the next road hog victim. Bill and Allison spend a perfect day  ruining about a dozen cars in all. They arrive at the Jack Frost Ford dealer at 750 S La Brea (left, now lost), with the dwellings and two-car garage along 5282 W 8th Street appearing behind them (above). Other scenes were staged near Silver Lake Blvd. and Bellevue, filmed from different angles, and a block further north along Vendome at Marathon, just a block south from the steps where Laurel & Hardy filmed The Music Box (1932). Perhaps we’ll cover these in a later post.

ruining about a dozen cars in all. They arrive at the Jack Frost Ford dealer at 750 S La Brea (left, now lost), with the dwellings and two-car garage along 5282 W 8th Street appearing behind them (above). Other scenes were staged near Silver Lake Blvd. and Bellevue, filmed from different angles, and a block further north along Vendome at Marathon, just a block south from the steps where Laurel & Hardy filmed The Music Box (1932). Perhaps we’ll cover these in a later post.

Here’s where Buster fits in. This frame with Bill and Alison being cut off looks north up Cahuenga from Willoughby (notice the street sign) toward the same storage building on the corner of Santa Monica Blvd. What’s striking is the Keaton Studio is already demolished, replaced in part by the white KMTR radio station building (now also demolished), while the pitched roof of the old Metro Studio headquarters stands behind a “VOC” billboard. Buster recorded an interview at this station many years later.

Here’s where Buster fits in. This frame with Bill and Alison being cut off looks north up Cahuenga from Willoughby (notice the street sign) toward the same storage building on the corner of Santa Monica Blvd. What’s striking is the Keaton Studio is already demolished, replaced in part by the white KMTR radio station building (now also demolished), while the pitched roof of the old Metro Studio headquarters stands behind a “VOC” billboard. Buster recorded an interview at this station many years later.

Click to enlarge – matching the 1932 movie frame annotated with a 1938 aerial view both looking north. The Keaton Studio stood between Cahuenga and Lillian Way (blue lines) and Eleanor and Romaine. KMTR sits on the west side of the studio site, the east side is a vacant lot. The former headquarters building for the Metro Studios below Keaton’s studio, which shut down in 1924 to join M-G-M in Culver City, is still standing in 1938.

Click to enlarge – matching the 1932 movie frame annotated with a 1938 aerial view both looking north. The Keaton Studio stood between Cahuenga and Lillian Way (blue lines) and Eleanor and Romaine. KMTR sits on the west side of the studio site, the east side is a vacant lot. The former headquarters building for the Metro Studios below Keaton’s studio, which shut down in 1924 to join M-G-M in Culver City, is still standing in 1938.

It wasn’t feasible to upgrade Buster’s small studio to make talking pictures, so after Keaton moved to M-G-M in 1928 his studio sat vacant until it was demolished in 1931. For comparison this photo above also looks north at the storage building clock tower (upper left) and the pitched roof of the back of the former Metro headquarters before KMTR was built. The large, dark, barn-like structure near the center is the Keaton Studio enclosed filming stage, shortly before it was demolished. HollywoodPhotographs.com.

It wasn’t feasible to upgrade Buster’s small studio to make talking pictures, so after Keaton moved to M-G-M in 1928 his studio sat vacant until it was demolished in 1931. For comparison this photo above also looks north at the storage building clock tower (upper left) and the pitched roof of the back of the former Metro headquarters before KMTR was built. The large, dark, barn-like structure near the center is the Keaton Studio enclosed filming stage, shortly before it was demolished. HollywoodPhotographs.com.

Here’s a 1938 view of KMTR where Buster’s studio once stood. The photo archive misidentifies the address as “La Brea”, but you can see the storage building to the left, and the series of buildings here match the profile in the 1938 aerial view above. LAPL.

Here’s a 1938 view of KMTR where Buster’s studio once stood. The photo archive misidentifies the address as “La Brea”, but you can see the storage building to the left, and the series of buildings here match the profile in the 1938 aerial view above. LAPL.

Studying vintage movie exteriors always reveals new surprises. A recent post about Keaton’s Seven Chances (1924) shows Buster fled from a mob of angry jilted brides by running north up Vine Street, revealing the front corner of his studio in the background (above) as he crosses Eleanor (link to detailed post HERE).

Studying vintage movie exteriors always reveals new surprises. A recent post about Keaton’s Seven Chances (1924) shows Buster fled from a mob of angry jilted brides by running north up Vine Street, revealing the front corner of his studio in the background (above) as he crosses Eleanor (link to detailed post HERE).

This circa 1930 aerial view above looking NW shows Buster’s path up Vine crossing Eleanor (arrow) and the Keaton Studio between Cahuenga and Lillian Way (blue lines). Notice the large barn-like filming stage, and the clock tower of the storage building. See Seven Chances post HERE for more details.

This circa 1930 aerial view above looking NW shows Buster’s path up Vine crossing Eleanor (arrow) and the Keaton Studio between Cahuenga and Lillian Way (blue lines). Notice the large barn-like filming stage, and the clock tower of the storage building. See Seven Chances post HERE for more details.

Compare this similar view, circa 1931, also showing Buster’s path north up Vine (arrow), and the corner of Willoughby and Cahuenga where Fields filmed (X). The Keaton Studio and large filming stage once standing between the blue lines are fully demolished, with the small KMTR buildings now standing on the west side of the lot.

Compare this similar view, circa 1931, also showing Buster’s path north up Vine (arrow), and the corner of Willoughby and Cahuenga where Fields filmed (X). The Keaton Studio and large filming stage once standing between the blue lines are fully demolished, with the small KMTR buildings now standing on the west side of the lot.

Another startling view, this 1923 photo looking SE shows the Keaton Studio between the blue lines, and Bill’s car on the corner of Willoughby (X). Not only was the Keaton Studio demolished when Fields filmed in 1932, but all of the Metro Studio buildings and exterior sets between the red lines were demolished as well. HollywoodPhotographs.com.

Another startling view, this 1923 photo looking SE shows the Keaton Studio between the blue lines, and Bill’s car on the corner of Willoughby (X). Not only was the Keaton Studio demolished when Fields filmed in 1932, but all of the Metro Studio buildings and exterior sets between the red lines were demolished as well. HollywoodPhotographs.com.

Taken from the storage building, a modern view south of the Keaton Studio site between the blue lines running north from Romaine to Eleanor, and Bill’s corner of Willoughby and Cahuenga (X).

Taken from the storage building, a modern view south of the Keaton Studio site between the blue lines running north from Romaine to Eleanor, and Bill’s corner of Willoughby and Cahuenga (X).

Please check out my YouTube channel, including new visual discoveries showing how Buster Keaton made The General. I wrote its musical score, the Paddlewheel Rag, back in 1975, and employed the Musescore app to record it for the video.

Google Maps link to Willoughby at Cahuenga HERE

October 14, 2023

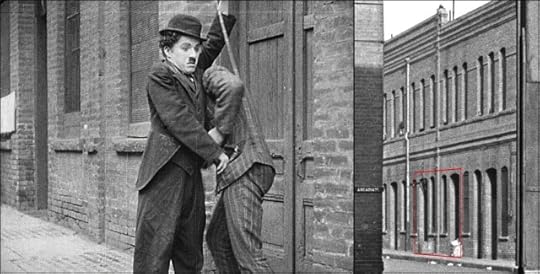

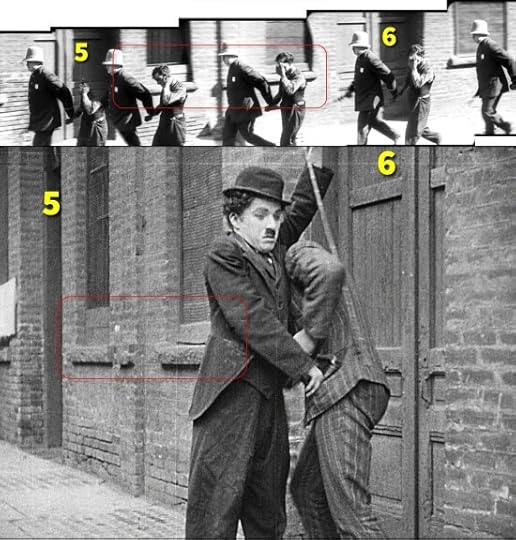

Chaplin, Keaton, and Coogan on Sanchez Street – Three Films Revealed in a Brief Glimpse during The Kid

Accolades aside, Chaplin’s masterpiece The Kid preserves a treasure trove of visual history, including Olvera Street near the Plaza de Los Angeles, and the Chaplin-Keaton-Lloyd Alley in Hollywood. It’s complicated (more below), but The Kid also captures the precise spot where Chaplin filmed scenes from Police (1916), Buster Keaton filmed scenes from Neighbors (1920), and Jackie Coogan filmed scenes from My Boy (1921), all south of the Plaza along Sanchez Street behind the Garnier Building.

As explained in my Chaplin book Silent Traces, in other posts on this blog, and in my new YouTube video The Kid – Part Two, when Charlie rescues Jackie Coogan from an orphanage truck, the south end of Sanchez appears in the background as they turn right onto Arcadia Street (above left – click to enlarge). Likewise, during Neighbors a cop drags Buster by the hand around the corner from Arcadia onto Sanchez, straight into a cement lamp post. With the aid of a movie frame from The Kid, this post shows how scenes from Police, Neighbors, and My Boy were all filmed behind the Garnier Building, part of which survives today as the Chinese American Museum https://camla.org/.