John Bengtson's Blog, page 4

January 14, 2023

Wonderful Wanda Wiley … Who?

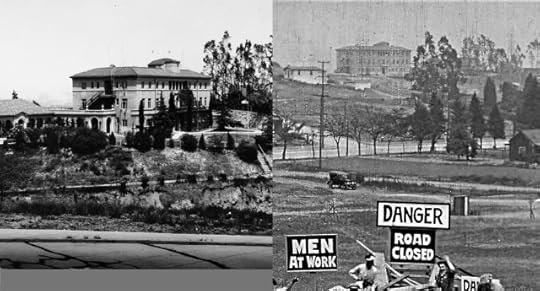

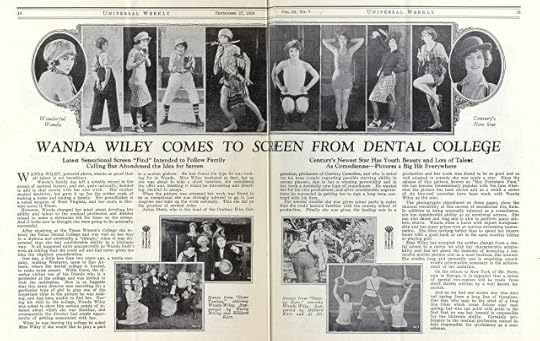

Wonderful Wanda Wiley was a spirited, athletic silent film comedienne, whose charm and girl-next-door appeal made her the female equivalent of Harold Lloyd’s “All-American Boy” (sometimes she even wore glasses). Ever ready, she bravely rolled down stairways, dived on cement sidewalks, and jumped between moving automobiles (see further below), anything for a laugh, matching her male colleagues blow by blow. Despite her slapstick antics, Wanda also posed for glamor publicity stills, above – read more on Lantern Media.

Wanda made a series of wonderful silent short comedies for Century Studios at Universal between 1924-1927. While most of her films are sadly lost, thanks to silent film superheroes Ben Model, Steve Massa, and Joseph Blough, you can enjoy some of her work on YouTube. This post highlights Wanda’s captivating comedy A Thrilling Romance (1927), where she plays a struggling author. On their Silent Comedy Watch Party YouTube link HERE, you can enjoy Ben’s musical accompaniment for the film along with Steve’s discussion of Wanda’s career. Joseph’s YouTube link HERE presents a silent but more visually clear copy of the film.

Wanda made a series of wonderful silent short comedies for Century Studios at Universal between 1924-1927. While most of her films are sadly lost, thanks to silent film superheroes Ben Model, Steve Massa, and Joseph Blough, you can enjoy some of her work on YouTube. This post highlights Wanda’s captivating comedy A Thrilling Romance (1927), where she plays a struggling author. On their Silent Comedy Watch Party YouTube link HERE, you can enjoy Ben’s musical accompaniment for the film along with Steve’s discussion of Wanda’s career. Joseph’s YouTube link HERE presents a silent but more visually clear copy of the film.

A Thrilling Romance is great fun, and it was exciting to discover Wanda’s on-screen charms, a talented star I’d never heard of before (ad above). I highly encourage you to enjoy her film. But the movie is also a remarkable time-travel machine, offering so many views of early Hollywood that this first post will cover only rare, perhaps unique views along Vine Street, including the long lost Famous Players – Lasky Studio.

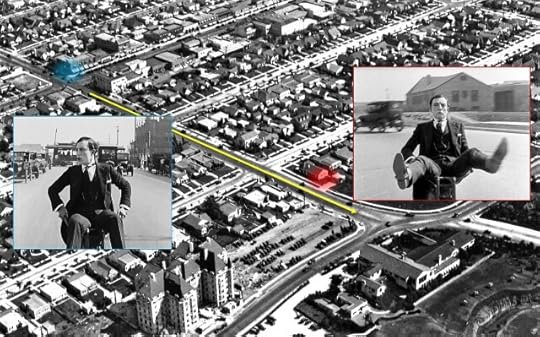

Hollywood fans may know the small barn where Cecil B. De Mille filmed The Squaw Man in 1914, and later relocated to serve as the Hollywood Heritage Museum, originally stood at the SE corner of Selma and Vine as part of the Famous Players – Lasky Studio. Click to enlarge – this 1921 aerial view above looks north – the Selma and Vine Lasky barn highlighted. But pay attention to the lower left corner of Sunset and Vine. Marc Wanamaker – Bison Archives.

Hollywood fans may know the small barn where Cecil B. De Mille filmed The Squaw Man in 1914, and later relocated to serve as the Hollywood Heritage Museum, originally stood at the SE corner of Selma and Vine as part of the Famous Players – Lasky Studio. Click to enlarge – this 1921 aerial view above looks north – the Selma and Vine Lasky barn highlighted. But pay attention to the lower left corner of Sunset and Vine. Marc Wanamaker – Bison Archives.

When Wanda, pictured here in 1927 paired with the 1921 aerial view, chases after a bag of stolen money, she runs down Vine with the rarely photographed SUNSET corner of the Famous Players studio behind her.

When Wanda, pictured here in 1927 paired with the 1921 aerial view, chases after a bag of stolen money, she runs down Vine with the rarely photographed SUNSET corner of the Famous Players studio behind her.

Click to enlarge – this 1924 aerial view at left is color-coded to Wanda’s 1927 view. At back in pink stands the Taft Building at Hollywood and Vine, built in 1923, the yellow spot marks the Sunset corner of Famous Players, and the star marks Wanda among the homes near 1415 Vine Street. HollywoodPhotographs.com.

Click to enlarge – this 1924 aerial view at left is color-coded to Wanda’s 1927 view. At back in pink stands the Taft Building at Hollywood and Vine, built in 1923, the yellow spot marks the Sunset corner of Famous Players, and the star marks Wanda among the homes near 1415 Vine Street. HollywoodPhotographs.com.

Click to enlarge – a reverse view, circa 1918, of the Sunset and Vine corner of Famous Players, Wanda standing among the now lost early residences. USC Digital Library.

Click to enlarge – a reverse view, circa 1918, of the Sunset and Vine corner of Famous Players, Wanda standing among the now lost early residences. USC Digital Library.

Click to enlarge, this time a 1919 aerial view of Famous Players, looking south down Vine, again matched with Wanda looking north. Marc Wanamaker – Bison Archives.

Click to enlarge, this time a 1919 aerial view of Famous Players, looking south down Vine, again matched with Wanda looking north. Marc Wanamaker – Bison Archives.

Above, a better view north of the Taft Building. USC Digital Library.

Above, a better view north of the Taft Building. USC Digital Library.

Above, these scenes filmed looking north reveal the staggered walls that once lined the west side of Vine between De Longpre and Leland Way. I am unable to locate any photos of these long lost homes.

Click to enlarge – a much closer view of the 1924 aerial photo looking north. Wanda and her hero taxi driver Earl McCarthy stand on the west side of Vine (star), with the white porch arches of 1415 Vine Street behind them.

Click to enlarge – a much closer view of the 1924 aerial photo looking north. Wanda and her hero taxi driver Earl McCarthy stand on the west side of Vine (star), with the white porch arches of 1415 Vine Street behind them.

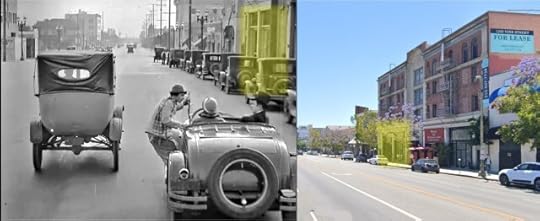

As mentioned, despite her glamor and charm, Wanda was also a slapstick heroine. That’s her leaping between moving automobiles, heading south down Vine St.

View south towards the Colehurst Apartments, 1106 N. Vine, left at back.

The St. George Court Apartments at 1245 Vine

Click to enlarge – vintage views of the Colehurst Apartments (left) and the St. George Court Apartments (above) appearing with Wanda. The Colehurst stands on the NE corner of Santa Monica Blvd. and Vine, a short block from the former Buster Keaton Studios. Buster filmed at this Santa Monica and Vine intersection several times, but only before the Colehurst was built in 1924. LAPL – USC Digital Library.

Click to enlarge – vintage views of the Colehurst Apartments (left) and the St. George Court Apartments (above) appearing with Wanda. The Colehurst stands on the NE corner of Santa Monica Blvd. and Vine, a short block from the former Buster Keaton Studios. Buster filmed at this Santa Monica and Vine intersection several times, but only before the Colehurst was built in 1924. LAPL – USC Digital Library.

Above, Wanda spills down the cement stairway of her apartment at 327 Beaudry Ave., dives on the sidewalk among many scenes filmed on Cahuenga, near Selma, the favorite Hollywood filming block for Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and Harold Lloyd, and even visits the frequently filmed cliffs overlooking Santa Monica Canyon. Details to follow in a later Wanda Wiley post – stay tuned.

Click to enlarge – Universal Weekly September 17, 1924 Vol. 20 No. 7 – Lantern Media

Wanda Wiley becomes now the fourth fantastic silent film comedian brought to my attention for the first time by Ben Model. Aside from Wanda, I only became aware of the delightful Alice Howell comedies (Alice Howell Collection), the Doug MacLean light comedies (The Douglas MacLean Collection), and the pre-talkie films of Edward Everett Horton (Edward Everett Horton: 8 Silent Comedies), because Ben had first tirelessly assembled, restored, scored, and released these essential early films to home video. I’ve posted stories about these releases from Ben elsewhere on my blog.

It’s tragic Wanda has been almost completely forgotten, and that nearly all of her films are lost. But you can enjoy several of her films on Joseph Blough’s YouTube Channel, including Queen of Aces (1925) HERE, Won By Law (1925) HERE, and Jane’s Trouble (1926) HERE, as well as A Thrilling Romance posted below. I hope you’ll check my YouTube Channel as well.

Below, looking north up Vine toward Leland Way, close to where Wanda stands on Vine near the top of this post.

December 24, 2022

Hiding in plain sight – more cinematic magic from Buster Keaton’s Go West

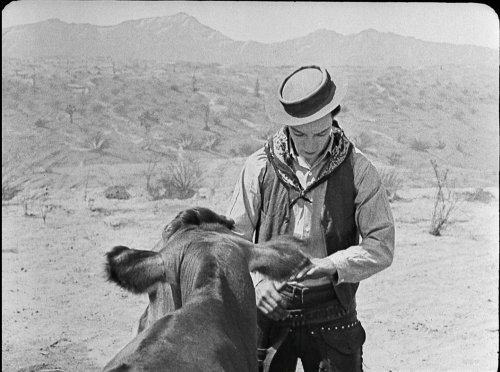

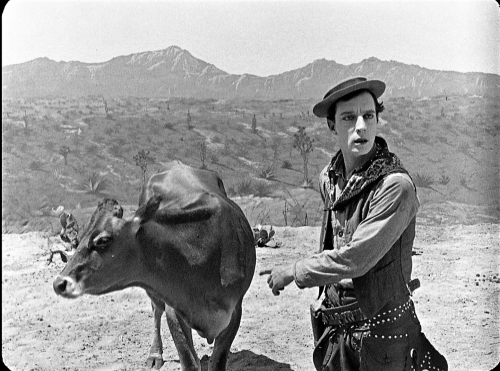

Known only as “Friendless,” Buster finds himself working on an Arizona cattle ranch during Go West. There he meets Brown Eyes the cow when he kindly removes a painful rock stuck in her hoof. Soon after she returns the favor by interceding when a bull comes charging at Buster. Friendless no more, Buster and Brown Eyes are inseparable for the rest of the film.

Above, the touching scene when Buster first realizes another living being, Brown Eyes, actually likes him, has always struck me as perhaps the most sincerely emotional scene portrayed in Keaton’s work. But as we’ll see a bit later below, the scene also contains some cinematic magic, hiding in plain sight.

Above, the touching scene when Buster first realizes another living being, Brown Eyes, actually likes him, has always struck me as perhaps the most sincerely emotional scene portrayed in Keaton’s work. But as we’ll see a bit later below, the scene also contains some cinematic magic, hiding in plain sight.

Now fast friends, Buster later protects Brown Eyes from being seared by a red-hot cattle brand by painlessly shaving a brand mark on her instead. Above, Buster shows his tonsorial handiwork to the rancher.

Now fast friends, Buster later protects Brown Eyes from being seared by a red-hot cattle brand by painlessly shaving a brand mark on her instead. Above, Buster shows his tonsorial handiwork to the rancher.

Next, in a scene that echoes Buster dislodging the rock from Brown Eye’s hoof, the rancher’s daughter, played by Kathleen Myers, beckons Buster to join her beside a well to help remove a splinter from her hand.

Next, in a scene that echoes Buster dislodging the rock from Brown Eye’s hoof, the rancher’s daughter, played by Kathleen Myers, beckons Buster to join her beside a well to help remove a splinter from her hand.

Looking closely (click to enlarge), both scenes were filmed in front of a painted backdrop. A prop well was added for Kathleen’s scene, but matching painted details appear in both shots. Very clever Buster!

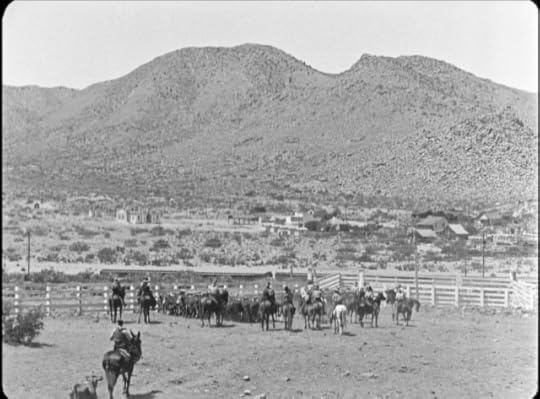

As first documented in my book Silent Echoes, and in this recent post updated with wonderful color photos taken by dedicated EPA attorney and devoted Keaton fan Marie Muller, Keaton filmed the ranch scenes at Tap Duncan’s Valley Ranch more than 50 miles north of Kingman, Arizona, and the cattle loading scenes in Hackberry, located along historic Route 66 about 20 miles NE from Kingman, and 30 miles south of the ranch. Above, matching views at Hackberry as they prepare the cattle to board the train – photo Marie Muller.

Above, knowing she will be transported by train to the slaughter house, Buster pleads to spare Brown Eye’s life, presented as if filmed at the Hackberry loading dock. Having visited Hackberry in person, and relishing the high definition details visible in the film’s Blu-ray release, I studied the above scene closely, hopeful some ridge lines in the background might match up.

Above, knowing she will be transported by train to the slaughter house, Buster pleads to spare Brown Eye’s life, presented as if filmed at the Hackberry loading dock. Having visited Hackberry in person, and relishing the high definition details visible in the film’s Blu-ray release, I studied the above scene closely, hopeful some ridge lines in the background might match up.

That’s when I realized Buster had staged these two emotional scenes, first meeting Brown Eyes, and later pleading for her life, in front of the same painted backdrop. Another bit of cinematic magic, hiding in plain sight. Very clever indeed.

The same painted backdrop also appears in this publicity still above (click to enlarge), one of a series of stills of Buster posing with regional freight cars staged with appropriate painted backdrops such as northern snow, southern cotton fields, and eastern rolling hills. While I have no access to contemporary records confirming this, logic dictates these painted backdrop scenes were filmed in Hollywood at Buster’s studio, under his complete control, and not at some remote, dusty ranch.

I discovered these painted backdrops preparing my Go West visual essay for the 2021 Eureka Entertainment Masters of Cinema release of Go West, along with Keaton’s Our Hospitality and College. With thanks to Kino-Lorber, the visual essay I prepared for KL about College is also included in the new Eureka release.

I discovered these painted backdrops preparing my Go West visual essay for the 2021 Eureka Entertainment Masters of Cinema release of Go West, along with Keaton’s Our Hospitality and College. With thanks to Kino-Lorber, the visual essay I prepared for KL about College is also included in the new Eureka release.

Another special effect – the upper floors are painted on glass

Though considered a lesser Keaton film, Go West remains a staggering accomplishment. Think of the logistics. Buster filmed for weeks in the Arizona desert, hundreds of miles from home, while enduring the summer heat. Buster worked with several farm animals, training them to perform on command, and wrangled a herd of at least 100 live cattle on real downtown streets, at 4th and Merrick near the former LA Santa Fe freight yard (above). Buster staged many sequences atop moving trains, presaging the even more elaborate scenes that would appear later in The General. And last, Buster employed many special visual effects so convincingly, including the painted backdrops revealed here, we don’t even notice. It all appears effortless on the screen thanks to Buster Keaton’s incredible talent as a comedian and filmmaker.

Check out the videos (11 now) about Buster, Charlie Chaplin, and Harold Lloyd hosted on my YouTube Channel.

Below, along Route 66, the Hackberry ridgeline appearing above – zoom in for a closer look.

November 30, 2022

Buster Keaton’s “Electric House” Home

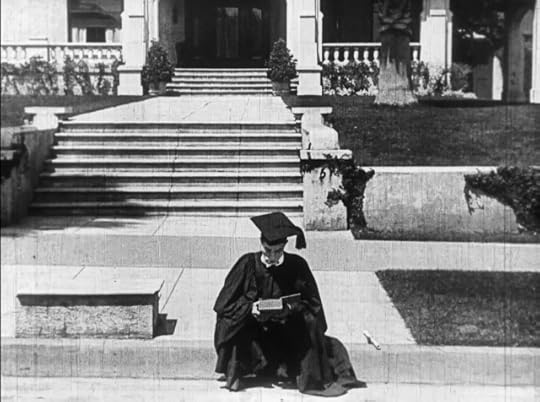

Buster filmed the graduation scenes from The Electric House (1922) at a commercial site still standing, just blocks away from his once magnificent real-life home (above) appearing later in the film.

Buster filmed the graduation scenes from The Electric House (1922) at a commercial site still standing, just blocks away from his once magnificent real-life home (above) appearing later in the film.

The film opens with Buster mistakenly receiving the electrical engineering degree intended for broken-nosed character actor Steve Murphy above, who later cons Buster in Cops (1922 – 2nd from right), and holds him hostage in Sherlock Jr. (1924 – far right).

The film opens with Buster mistakenly receiving the electrical engineering degree intended for broken-nosed character actor Steve Murphy above, who later cons Buster in Cops (1922 – 2nd from right), and holds him hostage in Sherlock Jr. (1924 – far right).

The graduation ceremony was filmed inside an interior decorator shop at 2121 W Pico. The storefront still exists today. Above, the initial clue was the 2120 address of a car painting garage across the street (you can read “PAINTING DEPARTMENT” (expanded) on the interior back wall).

The graduation ceremony was filmed inside an interior decorator shop at 2121 W Pico. The storefront still exists today. Above, the initial clue was the 2120 address of a car painting garage across the street (you can read “PAINTING DEPARTMENT” (expanded) on the interior back wall).

Next, you can read “..OR DECORATORS” painted (reversed) on the store window, and “..IRE THEA..” (reversed) reflected in the garage window. Assuming “THEA” referred to a theater, I checked odd-numbered theater addresses proximate to “2120,” and the Empire Theater at 2129 W Pico quickly confirmed the location. While the garage building is gone, Buster’s graduation site and the theater building remain standing.

Next, you can read “..OR DECORATORS” painted (reversed) on the store window, and “..IRE THEA..” (reversed) reflected in the garage window. Assuming “THEA” referred to a theater, I checked odd-numbered theater addresses proximate to “2120,” and the Empire Theater at 2129 W Pico quickly confirmed the location. While the garage building is gone, Buster’s graduation site and the theater building remain standing.

Buster’s graduation took place just a few blocks away at 59 Westmoreland Place, the stately mansion also appearing in the film that was Buster’s home at the time. Above, Buster exits a limo in front of his real-life home.

Buster’s graduation took place just a few blocks away at 59 Westmoreland Place, the stately mansion also appearing in the film that was Buster’s home at the time. Above, Buster exits a limo in front of his real-life home.

Mistaken to be an electrical engineer, Buster is immediately hired to upgrade Big Joe Robert’s mansion. The estate appearing in the film near Hoover and Pico, 59 Westmoreland Place, was in fact Buster and Natalie’s home during the time of filming. Considering Buster was still making short films, barely two years into his independent filmmaker career, his (Natalie’s?) choice of residence at the time seems quite impressive. You can read the “59” address behind Buster, the “9” a bit obscured by the vine.

Mistaken to be an electrical engineer, Buster is immediately hired to upgrade Big Joe Robert’s mansion. The estate appearing in the film near Hoover and Pico, 59 Westmoreland Place, was in fact Buster and Natalie’s home during the time of filming. Considering Buster was still making short films, barely two years into his independent filmmaker career, his (Natalie’s?) choice of residence at the time seems quite impressive. You can read the “59” address behind Buster, the “9” a bit obscured by the vine.

Buster and the Talmadges beside the front porch

What images of the home don’t convey is that the mansion was part of an ill-fated development. Restricted so that only palatial homes could be built on its flat, expansive lots, Westmoreland Place failed to catch on, and as the elite increasingly chose to live further west, in more secluded and hilly neighborhoods, most of the giant lots sat empty. Built in 1909, Buster’s home stood two empty parcels north of, and in full view of, the busy Pico trolley line, and was just steps from the low-rent commercial center where Buster received his diploma earlier in the film.

This 1920 map shows Buster’s 59 home (box), one of the few homes in the purple shaded Westmoreland development, two empty lots north of the busy Pico trolley line. Although the house was very impressive, especially for a man as young as Buster, it was not the best locale. Adjacent to ordinary commercial streets and an active trolley line, the neighborhood lacked the prestige and seclusion befitting a rising star, prompting the Keatons’ next move further west to upscale Ardmore Avenue. I now better understand why Natalie wanted to move.

This 1920 map shows Buster’s 59 home (box), one of the few homes in the purple shaded Westmoreland development, two empty lots north of the busy Pico trolley line. Although the house was very impressive, especially for a man as young as Buster, it was not the best locale. Adjacent to ordinary commercial streets and an active trolley line, the neighborhood lacked the prestige and seclusion befitting a rising star, prompting the Keatons’ next move further west to upscale Ardmore Avenue. I now better understand why Natalie wanted to move.

A matching vintage aerial view, Buster’s home (left box), clearly visible from the Pico trolley, was just blocks from the graduation location (right box). So few homes were built at Westmoreland that by 1923 civic leaders considered condemning the development site as a desperately-needed urban park. Eventually the covenants were overturned, and apartment blocks began to fill the empty lots. Buster’s home was demolished in 1979. Residential historian Duncan McGinnis provides a full history of 59 Westmoreland Place – read more HERE.

A matching vintage aerial view, Buster’s home (left box), clearly visible from the Pico trolley, was just blocks from the graduation location (right box). So few homes were built at Westmoreland that by 1923 civic leaders considered condemning the development site as a desperately-needed urban park. Eventually the covenants were overturned, and apartment blocks began to fill the empty lots. Buster’s home was demolished in 1979. Residential historian Duncan McGinnis provides a full history of 59 Westmoreland Place – read more HERE.

Buster’s graduation site – 2121 W Pico

Check out the 11 videos about Buster, Charlie Chaplin, and Harold Lloyd hosted on my YouTube Channel.

Check out the 11 videos about Buster, Charlie Chaplin, and Harold Lloyd hosted on my YouTube Channel.

Below, the approximate location, now renumbered, of Buster’s once grand home at 59 Westmoreland Place.

November 12, 2022

New revelations about Safety Last! and The Kid

Two recent YouTube videos revealing new details from Harold Lloyd’s Safety Last!, and Charlie Chaplin’s The Kid, are now uploaded to my YouTube Channel. The channel includes a playlist of other video presentations hosted by museums and other groups.

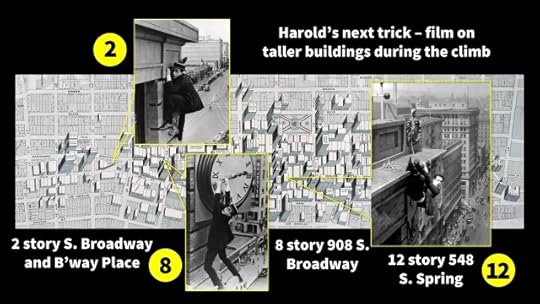

Hang on – how Harold Lloyd made Safety Last!A few sample slides below, see how Harold filmed atop increasingly taller buildings, five in all, how a single scene was filmed atop three different buildings, also scenes near USC, MacArthur Park, and at the Chaplin-Keaton-Lloyd Alley in Hollywood.

The background music is a piano rag I wrote 47 years ago (!), and transcribed as a Musescore file. Here’s a YouTube video showing a computer (not me) playing the piano rag.

The background music is a piano rag I wrote 47 years ago (!), and transcribed as a Musescore file. Here’s a YouTube video showing a computer (not me) playing the piano rag.

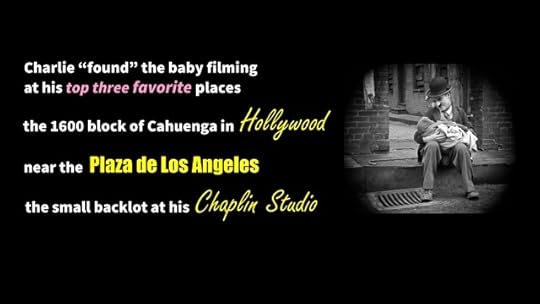

Chaplin’s beautiful scores for The Kid accompany this detailed study of the movie’s opening scenes, showing step by step views of early Hollywood, and the Plaza/Chinatown neighborhoods downtown, to reveal where Edna Purviance lost and Charlie found the baby who became “The Kid.”

Posting these videos has been a lot of fun. Rather than explain, it’s far more satisfying to show these details, so viewers can see for themselves. My blog has numerous other posts about Safety Last! and The Kid, see below.

Posting these videos has been a lot of fun. Rather than explain, it’s far more satisfying to show these details, so viewers can see for themselves. My blog has numerous other posts about Safety Last! and The Kid, see below.

https://silentlocations.com/category/safety-last/

https://silentlocations.com/category/the-kid/

Thank you so much – this is now video number 11, and I hope to continue uploading new videos every month or so to my YouTube Channel.

October 29, 2022

The Kid, Cops, Intolerance revealed in a 125 year old photo

When the great silent comedians filmed the streets of LA one hundred or more years ago, many of those settings were already decades old. Focusing on a single vintage photo, let’s explore one of the most fascinating film locations in all of cinematic history.

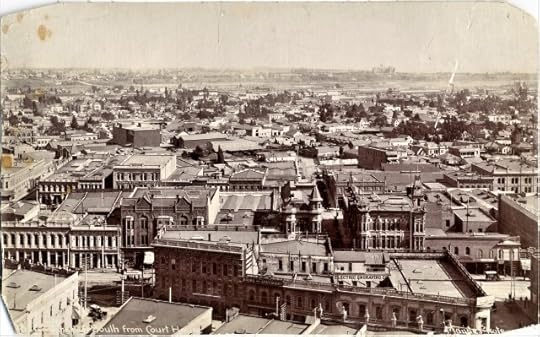

Click to enlarge – this amazing 1897 photo looks east from the tower of the former Los Angeles County Court House once standing at Temple and Broadway in downtown. The prominent corner building facing us just right of center, with the pointed cap tower, is the former Amestoy Building at Main and Market. The left-right street in the foreground is Main Street, with Spring Street along the bottom merging into it. Looming on the horizon at right stands the “cozy” former Los Angeles Orphanage at 917 South Boyle Avenue, built in 1890. California State Library.

Click to enlarge – a closer view, way at back. The center of the image reveals the narrow intersection of Ducommun Street and Labory Lane, marked by a very narrow two-story triangle building at 412 Ducommun. Do you see it?

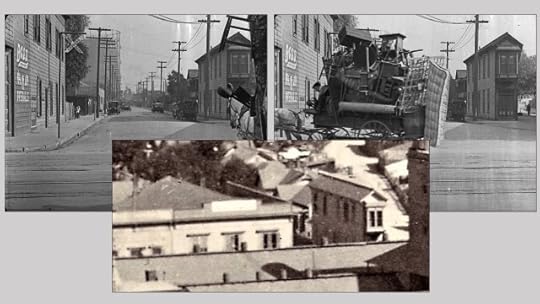

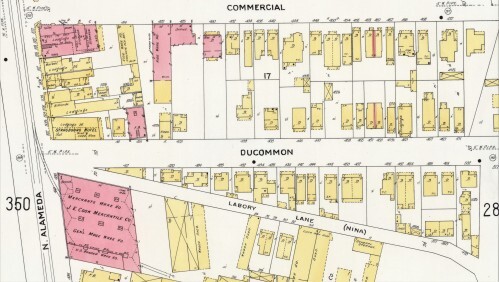

If I could time travel to silent movie locations, after first visiting Court Hill (read more HERE), this would be stop number two, the narrow corner of Ducommun and Labory, just east of Alameda street, a few blocks from the Plaza de Los Angeles. To begin, this corner was Buster Keaton’s favorite place to film, he staged a dozen scenes here for The Goat and Cops, far more so than anywhere else in town. Above, Buster practices signalling a left-hand turn during Cops. That’s the Hotel Strasbourg to the left in all three images across from the triangle building, more later.

Next, Charlie Chaplin filmed the rooftop chase from The Kid atop these homes on Ducommun, and fought with the orphanage official in the truck driving down Labory Lane to the right. Looking close, the yellow line marks the foreground chimney in each image, the red arrow marks Charlie’s spot on the roof. The prominent 3-story Amelia Street Public School appears at back to the right in each image, its roof lowered half a floor. The Ducommon natural gas holding tank behind Charlie wasn’t yet built in 1897.

Click to enlarge – a quartet of images looking east at the triangle building, with Ducommun to the left, Labory Lane to the right. Upper left is Derby Days, upper right is an unidentified scene from Episode Two of the Brownlow-Gill Hollywood series, lower left is the Sennett comedy Call A Cop, and lower right is the Gaylord Lloyd comedy (Harold’s brother) Dodge Your Debts. The narrow building allowed filmmakers to show audiences both sides of a chase. A similar crazy filming corner stood nearby (read more HERE).

I’ve only just started, and could write ten more pages about Ducommun at Alameda, especially focusing on all the Keaton scenes. But in closing, this remarkable triangle building also appears during the “modern” sequence from D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance, when Robert Harron desperately seeks to rescue Mae Marsh from the Strasbourg Hotel. The same Strasbourg front door side panel – click to enlarge – appears at the far left of each frame; from The Goat at left, from Intolerance at center, and from Cops at right.

The 412 Ducommun triangle building likely appeared in dozens more films, and if it hadn’t been demolished in 1923, would likely have had more starring roles. In closing, above here’s a montage of some of the other Keaton scenes filmed at Alameda and Ducommun.

Click to enlarge – a 1906 Sanborn map, Vol 3 Page 279. LOC. Buster filmed many scenes from The Goat and Cops beside, and at the corner of, the Strasbourg Hotel. 415 Ducommun, the red brick building, is the home where the family loads their furniture onto Buster’s wagon. The “F.B.” marked on it stands for “Female Boarding,” a Sanborn euphemism for bordello.

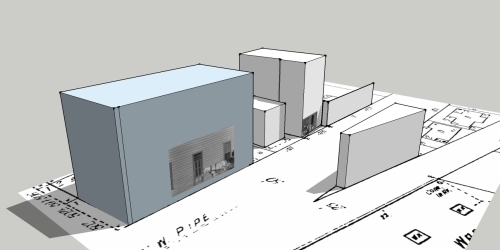

An early crude attempt at a 3D model. Imagine a fully realized virtual model where Buster made The Goat and Cops, Larry Semon filmed Frauds and Frenzies, and Charlie made The Kid. Any takers?

A special appeal – if I had the skill and resources to create a virtual 3D model of any historic LA film site, it would be of this long lost corner of Ducommun, Labory, and Alameda. It appears in many films, from many angles, and several vintage maps confirm the exact position of each building. If you know any 3D modeling expert who’d like a fun project, let me know, and I can supply all the files and images.

I now have TEN videos on my YouTube Channel. Check out To The Church – How Buster Keaton Made Seven Chances.

Below – Ducommun at Alameda today, completely rebuilt – spin around for a full view.

October 15, 2022

Harold Lloyd’s “Hot Water” Sherlock turkey troubles

Wrangling a live turkey on a trolley, forced to walk it home, overlapping Buster Keaton’s Sherlock Jr., even more visual history is now revealed from Harold Lloyd’s Hot Water (1924).

Newlywed Harold’s day is shattered when his better half calls to ask “hubby dear” to pick up a “few things for dinner” on the way home. Already overwhelmed with packages, lucky Harold wins the store raffle, a free live turkey we’ll call Tom. Harold and Tom somehow board a crowded trolley.

The trolley was a studio prop towed north past 162 S Lucerne Blvd, also seen here during Sherlock Jr. (1924). The evil henchman appearing to spy on Buster up the street, character actor Steve “Broken Nose” Murphy, is actually looking the wrong way.

Sherlock’s assistant Gillette (played by Ford West) pulls Buster over at 220 S Lucerne, a block to the south, behind from where Murphy is supposedly spying on them. More incongruous, the shot including all three actors (left), as Buster leaps onto the bike and they ride off, was filmed several blocks away, north of Beverly looking south down Larchmont.

Sherlock’s assistant Gillette (played by Ford West) pulls Buster over at 220 S Lucerne, a block to the south, behind from where Murphy is supposedly spying on them. More incongruous, the shot including all three actors (left), as Buster leaps onto the bike and they ride off, was filmed several blocks away, north of Beverly looking south down Larchmont.

Buster and Gillette take off north along the same route as the Hot Water turkey trolley, passing the same 162 S Lucerne home appearing with Harold. In all a dozen homes along S Lucerne appear with Buster and Gillette (numbers 158 to 256, although sometimes edited out of sequence) during their Lucerne ride. Of course, no sooner do they begin then Gillette immediately falls off of the bike (as reported HERE), leaving Buster unaware no one is driving. The scene was shot looking east along Eleanor from the corner of the Keaton Studio at Lillian Way (right), with Buster performing the fall for Ford West as his stunt double.

Buster and Gillette take off north along the same route as the Hot Water turkey trolley, passing the same 162 S Lucerne home appearing with Harold. In all a dozen homes along S Lucerne appear with Buster and Gillette (numbers 158 to 256, although sometimes edited out of sequence) during their Lucerne ride. Of course, no sooner do they begin then Gillette immediately falls off of the bike (as reported HERE), leaving Buster unaware no one is driving. The scene was shot looking east along Eleanor from the corner of the Keaton Studio at Lillian Way (right), with Buster performing the fall for Ford West as his stunt double.

As with many homes on N Beachwood appearing in Hot Water (see prior post) 162 S Lucerne has been remodeled, its three-arch open porch now enclosed for more floor space. The home stands on the NE corner of W 2d, just west of Larchmont, close to where Harold filmed other Hot Water scenes. The corner home appears in other silent comedies, at left in the Charles King 1926 comedy Please Excuse Me. Harold’s trolley passes by many other Larchmont-area homes during the lengthy scene, which remain to be documented. As expected, fussy Tom wrecks havoc, upsetting all the passengers.

As with many homes on N Beachwood appearing in Hot Water (see prior post) 162 S Lucerne has been remodeled, its three-arch open porch now enclosed for more floor space. The home stands on the NE corner of W 2d, just west of Larchmont, close to where Harold filmed other Hot Water scenes. The corner home appears in other silent comedies, at left in the Charles King 1926 comedy Please Excuse Me. Harold’s trolley passes by many other Larchmont-area homes during the lengthy scene, which remain to be documented. As expected, fussy Tom wrecks havoc, upsetting all the passengers.

Fed up, the conductors toss  Harold and Tom off the trolley, filmed looking west on Sunset Blvd approximately near Ogden Dr. As solved by historian and frequent contributor Paul Ayers, this single track Pacific Electric line ran on Sunset between Gardner Jct. and Laurel Canyon Blvd. from 1911 to 1924. Perhaps the line had already closed when Harold filmed here. Also looking west, the frame at right from the 1919 Lyons & Moran comedy Waiting at the Church (also HERE) shows matching tree and ridge lines, and even the same house with a white chimney to the right. Working with the Library of Congress Michael Aus has made these entertaining, little-known Lyons & Moran films available to eager fans. Visit his eBay listing, and his , where the sale proceeds benefit the Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum.

Harold and Tom off the trolley, filmed looking west on Sunset Blvd approximately near Ogden Dr. As solved by historian and frequent contributor Paul Ayers, this single track Pacific Electric line ran on Sunset between Gardner Jct. and Laurel Canyon Blvd. from 1911 to 1924. Perhaps the line had already closed when Harold filmed here. Also looking west, the frame at right from the 1919 Lyons & Moran comedy Waiting at the Church (also HERE) shows matching tree and ridge lines, and even the same house with a white chimney to the right. Working with the Library of Congress Michael Aus has made these entertaining, little-known Lyons & Moran films available to eager fans. Visit his eBay listing, and his , where the sale proceeds benefit the Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum.

Thrown from the trolley, as Harold leads Tom home, a distinctive broad building appears behind them. The curved details at the left reminded me of another scene from Sherlock Jr., where driverless Buster blissfully races west down Beverly from Larchmont toward the Wilshire Country Club. Buster’s scene is noteworthy, not only for his stuntwork, but for the rare photo depiction of the front of the club.

Thrown from the trolley, as Harold leads Tom home, a distinctive broad building appears behind them. The curved details at the left reminded me of another scene from Sherlock Jr., where driverless Buster blissfully races west down Beverly from Larchmont toward the Wilshire Country Club. Buster’s scene is noteworthy, not only for his stuntwork, but for the rare photo depiction of the front of the club.

Buster cycles west along Beverly past Larchmont towards the prominent, rarely photographed front of the Wilshire Country Club at back.

Click to enlarge – matching details, the curve of the road, and more details below confirm the Wilshire Country Club appears behind Harold. As reported in The Larchmont Chronicle celebrating the club’s 2019 centennial, the original club house was demolished in 1971, its replacement demolished in 2001, and the resulting third clubhouse was further remodeled in 2008.

Caption from the Wilshire Country Club’s history page “The original Clubhouse completed in 1922 on the corner of Rossmore Ave. and Temple Street, which became Beverly Blvd. upon its construction through the golf course in 1924.” Given the dense foliage, this photo was taken well after Buster and Harold filmed here in 1924.

Matching views looking west of Harold and Tom walking along Beverly Dr from the near corner of S Arden Blvd, and the Rossmore corner of the Wilshire County Club one block further back.

Once the Wilshire Country Club crossed my radar, it suddenly became clear this odd street pattern to the left during Harold’s family car excursion shows the corner of the club, north up Rossmore from Beverly, with the club’s driveway traffic islands behind Harold, and the club parking lot to the right across the street. Narrow white posts outline the club parking lot in both images. See aerial view below.

For context, this aerial view looking SE shows Harold’s two scenes along Beverly. The narrow white posts in both movie frames outline the Wilshire Country Club parking lot across the street. LAPL.

Buster filmed Sherlock Jr. all around this neighborhood too. Here are just two of his many scenes matched to the same photo.

I again want to thank Zebra 3, a self-described film location hobbyist reporting on IMDb, for sharing all the locations he discovered as reported in this prior Harold’s Hot Water, Happy Days post. His insights prompted me to revisit Hot Water, resulting in this Part 2 post.

I now have TEN videos on my YouTube Channel. To learn more about Sherlock, check out Case Closed – How Buster Keaton Made Sherlock Jr.

Below, where Harold and Buster filmed at 162 S Lucerne

October 1, 2022

Flying “Lizzies of the Field” – Part 2

One of silent comedies’ craziest scenes, race cars zooming down a ramp, flying through the air, landing in a pile atop each other, marks the exciting climax to Lizzies of the Field (1924), the Mack Sennett Comedies Studio production recently restored and released by Dave Glass and Dave Wyatt as part of their striking two-disc Blu-ray release of nearly 20 comedies starring Billy Bevan. The two reel film, discovered in the Eye Filmmuseum archive, scanned by Lobster Films, and restored by Lobster and Dave Glass, is presented complete and in stunning detail for the first time. This prior post, Part One, shows where they filmed Lizzies along roads near the yet-to-be-built Griffith Park Observatory.

Brent Walker, author of Mack Sennett’s Fun Factory, reports the flying car stunt was a major event. Sennett sent not only all of his own studio cameramen, but also Alvin Knechtel of Pathe News, to document the crash. As Brent reports, the stunning scene had long been familiar, having been featured in compilation films including Robert Youngson’s 30 Years of Fun (1963), and in Paul Killiam’s The Fun Factory (1960), and The Great Chase (1962).

Brent writes at page 386 of his book the hill was located near Rowena St. and Armstrong St. near Silver Lake. When I contacted Brent, he recalled a script or other papers in the AMPAS Sennett Collection files had mentioned the jump being staged near this locale, while few other Sennett locations were ever referenced.

Click to enlarge – intrigued by the Blu-ray clarity of the film, I focused on the imposing hilltop building overlooking the jump site. After searching vintage photos on Calisphere, I quickly found it – the former Monte Sano Foundation at 2834 Glendale Blvd. USC Digital Library.

Click to enlarge – with this background reference point fixed, it became easy to orient the stunt filming site geographically. The Monte Sano building (red box) has given way to condominiums on re-named Waverly Drive, and Armstrong St. has since been re-named W Silver Lake Drive, but as Brent correctly reports, the crash stunt was staged along hills and fields SW from the corner of Rowena and Armstrong.

Knowing the locale, it’s clear to see this view looking to the NW shows Griffith Park, and the distinctive Beacon Hill in the background. Paul Ayers.

This current Google Maps view shows the path of the cars down the ramp, arrow, and the former site (red box) of the Monte Sano building.

Above, covered in this Part One post, matching views of the auto race appearing earlier in Lizzies along 2763 Glendower Ave.

Thanks again to Dave Glass and Dave Wyatt for their heroic work. Here’s the link to the Dave Glass YouTube channel, loaded with dozens of rare silent comedies.

I now have TEN videos on my YouTube Channel. If you like detective stories, check out Case Closed – How Buster Keaton Made Sherlock Jr.

Below, Shadowlawn Ave follows the slope of the auto jump ramp within the SW corner of Rowena and W Silver Lake Dr (formerly Armstrong).

September 17, 2022

Jackie Coogan’s Charlie Chaplin’s Lost LA Alley – The Rag Man

Jackie Coogan returned twice more to an LA alley where he made The Kid with Charlie Chaplin. Early LA streets, now lost, appear in Jackie’s The Rag Man (1925).

Jackie plays an orphan who becomes a successful junk dealer working with character actor Max Davidson as his guardian and business partner. As shown further below, Jackie (and Charlie) cross paths with Buster Keaton and Harry Langdon in downtown LA.

Jackie plays an orphan who becomes a successful junk dealer working with character actor Max Davidson as his guardian and business partner. As shown further below, Jackie (and Charlie) cross paths with Buster Keaton and Harry Langdon in downtown LA.

I was stunned to learn most of The Rag Man was filmed on location in New York, and as reported in Mark Phillips’ phenomenal NYC IN FILM blog, many of these vintage locales remain recognizable today – read all about The Rag Man at https://nycinfilm.com/2017/12/24/rag-man-1925/. Above, looking north at Sutton Place from E 57th. Mark’s work documenting New York based movies is extraordinary, impeccably photographed and researched. I strongly encourage you to check Mark’s blog for your favorite NYC movies.

Back in LA, compare Jackie’s frame with a matching frame from The Kid. Both show the same “ARCADIA” street sign on the wall across the way (you can actually read it if you enlarge Charlie’s frame). To the right in both frames is Sanchez Alley, running north from Arcadia towards the Plaza de Los Angeles. The north end of Sanchez remains today, but the southern end of Sanchez, perpendicular to Arcadia, which ran north-south from Main St to Los Angeles St, were all demolished for a freeway. Mark’s blog has some great aerial views of this spot.

Charlie filmed his scene from The Kid as if the orphanage truck was speeding around a street corner. The truck, out of necessity, was quite narrow. Jackie’s broader view shows the corner was in fact a narrow passageway between buildings leading to a rear loading dock, depicted below in another of Jackie’s films, My Boy (1921).

Jackie’s My Boy frame at the right (hosted on YouTube) shows the entrance was enclosed by a vertically raised and lowered gate. Eye Filmmuseum.

Jackie loads new merchandise onto his junk cart in front of the open gated entrance. His frame forms a virtual panoramic view of the Baker Building, as Buster flees the police running south down Arcadia from Main St towards Los Angeles St during Cops (1922). Mark astutely reports that Eddie Cline, Buster’s co-director for many of his early shorts, also directed The Rag Man. So Eddie must have felt quite at home here, after already directing Buster’s chase scene at the same spot.

Above, facing the Arcadia entrance way, in a view looking SE, a friendly preacher checks on Jackie. The NW corner of the Hotel de Paris building appears behind him – note the matching twin-curves within single curve arch details in both images. The full photo looks north up Arcadia from Los Angeles St towards Main St, passing midway the south end of Sanchez Alley.

Matching views north looking up Arcadia towards Main St, the Baker Building to the left. This was all lost to a modern freeway.

Above, closer views of the detailed columns outlining the Baker Building perimeter. Once the most glamorous building in town, it fell on hard times, later serving as headquarters for Good Will Industries, before being demolished for a freeway. LAPL

Click to enlarge – a panoramic view of the west side of Arcadia, with Harry Langdon in Feet of Mud (1924), the Plaza Jewelry Co. at 114 Arcadia, Jackie (center) and Buster at right.

Looking north from Arcadia Street and Sanchez Alley towards the Plaza de Los Angeles. The inset photo is the Baker Building facing Main. These early streets appear in dozens of films, including Chaplin’s Police (1916), and Keaton’s Neighbors (1920), covered in great detail in my Chaplin book Silent Traces at pages 107-112. To whet your appetite here below are pages 211 and 212 discussing Arcadia and the Baker Building.

In closing, do yourself a favor and check out Mark Phillips’ phenomenal NYC IN FILM blog, covering classic NYC films from all decades, and especially his in-depth coverage of The Rag Man at https://nycinfilm.com/2017/12/24/rag-man-1925/.

So much of early LA has been lost, but intriguing glimpses remain hidden in the background of silent film. Below, “Arcadia” is now an access road parallel to the freeway, viewed here looking at the north end of Sanchez. Rotate the image to see the freeway behind.

September 3, 2022

Harold Lloyd’s “Hot Water” “Happy Days” Home

Harold’s home stands on two different blocks and TV’s Happy Days Cunningham home appears nearby. So many new locales from Hot Water (1924) were found and shared by eagle-eyed reader Zebra 3, a self-described film location hobbyist, who shares what he finds on IMDb.

Hot Water, a parody of domestic bliss, is best known for its famous set pieces, including Harold’s attempt to ride a crowded streetcar while carrying armloads of groceries and a live turkey, and his disastrous inaugural outing in his new car, with his pesky in-laws in tow. Above Harold and live turkey arrive at 4056 W 7th Street, note the doorway address.

Above, a full view of the family home. Remarkably, all other Hot Water scenes presented as taking place in front of their home were filmed two miles away on N Beachwood Dr.

Above, Harold eagerly accepts delivery of the new family auto, with 575 N Beachwood at back. The distinctive porch has now been remodeled. The scene is presented as if in front of Harold’s 4056 home on W 7th, which is actually two miles away.

Above, Harold proudly presents the new family car to his wife portrayed by Jobyna Ralston, with 565 N Beachwood in the background. The distinctive trio of window arches were later removed. The audience was not expected to notice the discrepancy between the 4-digit address of the family home (4056), and the many 3-digit addresses appearing during the Beachwood scenes.

The family poses for a photo portrait before leaving on their inaugural auto tour, with 570 N Beachwood at back (see address behind Jobyna). The trio of stylish arched windows (box) peeks over the hedge.

A closer view of 570 N Beachwood as Jobyna delights at seeing Harold’s new family car.

Views south down Beachwood as Harold’s in-laws pile into the car. 565 Beachwood (box) originally had an arched entrance, but the homes down the street appear unchanged.

A far (left) and closer (middle) view of 565 N Beachwood, home to Harold’s friendly neighbor, who takes a photo portrait of the family in their new car. The Sanborn maps show the 565 home was originally “L” shaped, with only a front room to the right of the arched entrance. Now expanded, the remodeled home has front rooms on both sides of the front door.

The friendly neighbor prepares to take the Lloyd family portrait, with the porch entrance to 591 N Beachwood behind him. Visible further north, the duplex still standing at the NW corner of Clinton St.

A bad omen, no sooner does the Lloyd family embark on their maiden auto safari, they nearly collide with a milk cart. Notice the N 581 Beachwood home to the left originally did not have a stairway leading from the front door down the lawn to the sidewalk.

This studio interior scene shows Harold unloading his groceries inside the front door. The photo backdrop appears to be 522 N Beachwood, which also did not originally have a stairway leading from the front door down the lawn to the sidewalk.

As I report at page 161 of my Harold Lloyd book Silent Visions, Harold immediately gets in trouble by turning left around the wrong side of a traffic button, here the NE corner of W 1st and S Larchmont.

Also from my book, the cop lets Harold off with a harsh scolding. Always, ALWAYS, pass to the right side of a traffic button. 108 S Larchmont appears at back.

Back to new discoveries. Unbeknownst to Harold, a jubilant WWI veteran has accidentally lost his helmet in the street, seen here looking at the Los Angeles Tennis Club at the NW corner of N Cahuenga and Clinton.

Harold mistakes the helmet for a traffic button, and ever the good citizen, reverses course to drive properly around the right side. The corner home of 591 N. Cahuenga appears at back.

The big reveal, when the soldier stops to retrieve his helmet, this view looking south shows two-story 565 N Cahuenga at back. Decades later, the house portrayed the Cunningham family home during the hit 1970-80s sitcom Happy Days. But Harold filmed here first. Read all about the Happy Days home at Lindsay Blake’s I’m Not A Stalker filming locations website.

The big reveal, when the soldier stops to retrieve his helmet, this view looking south shows two-story 565 N Cahuenga at back. Decades later, the house portrayed the Cunningham family home during the hit 1970-80s sitcom Happy Days. But Harold filmed here first. Read all about the Happy Days home at Lindsay Blake’s I’m Not A Stalker filming locations website.

Above, the homeowner at 590 N Cahuenga screams “get off my lawn!” as Harold and family make a hasty retreat.

For context, this vintage photo shows the Los Angeles Tennis Club on the NW corner of N Cahuenga and Clinton, along with three views of Harold’s car. LAPL.

Avoiding the traffic buttons, the family speeds westerly along W 2nd past the corner of S Plymouth at right, near W 1st and Larchmont, another discovery made after my book was published.

From here on all hell breaks loose, taking the family across S Lafayette Park Place, Santa Monica, and past the former Hollywood fire station, all as reported in my book. Another discovery, reported on my blog soon after my book came out, the car careens out of control down Olive St downtown, the Bunker Hill film noir locale appearing in the The Turning Point (1952) above right.

I’ll save this for another post, but before Harold buys the car I’ve also found where Harold is ejected from the trolley on Sunset Blvd, approximately near Ogden Drive, and his route walking the turkey home along Beverly Drive past Arden Drive. Stay tuned for Part Two.

I’ll save this for another post, but before Harold buys the car I’ve also found where Harold is ejected from the trolley on Sunset Blvd, approximately near Ogden Drive, and his route walking the turkey home along Beverly Drive past Arden Drive. Stay tuned for Part Two.

661 Shatto Place – Punky Brewster

For even more Harold Lloyd – mid 1980s sitcom connections, check out where Harold filmed For Heaven’ Sake (1926) at 661 Shatto Place, appearing in the opening credits for Punky Brewster.

Again, let’s all give Zebra 3 a great big shout out for these incredible discoveries, and for sharing them with us, and on IMDb.

You can watch Hot Water streaming on YouTube at the Harold Lloyd channel.

Below, an April 2011 view of 575 N Beachwood, before the remodel, seemingly across the street from Harold’s family home at 4056 W 7th. You can explore up and down the street on your own.

August 21, 2022

Charlie Chaplin’s “Modern Times” Sanitarium Solved

Charlie Chaplin used the former Occidental College Hall of Letters (still standing) to portray the charity hospital where Edna Purviance delivers her baby in The Kid (1921). But “cured of a nervous breakdown but without a job” during Modern Times (1936), Charlie used the Mary Norton Clapp Library at the new Occidental College campus in Eagle Rock to portray the hospital where he leaves to start his life anew.

The library opened in 1923 with two entrances, the east entrance flanked by a pair of columns, and the more modest north entrance used by Chaplin. The south side has no entrance, and vintage photos confirm the west side of the library, now covered by a 1971 expansion of the building, also had no entrance. I had long been intrigued by this simple scene, which in fact, was the final unsolved exterior from the entire movie.

The library opened in 1923 with two entrances, the east entrance flanked by a pair of columns, and the more modest north entrance used by Chaplin. The south side has no entrance, and vintage photos confirm the west side of the library, now covered by a 1971 expansion of the building, also had no entrance. I had long been intrigued by this simple scene, which in fact, was the final unsolved exterior from the entire movie.

Click to enlarge – north end of Mary Norton Clapp Library – Occidental College

I want to thank reader Mark Smith who reached out with an intriguing inquiry that directly prompted this post. During his audio commentary to the Criterion Collection Blu-ray release of Modern Times, Chaplin biographer David Robinson explains “The building used for the exterior is Occidental College.”

Mark wondered if this would have been the old Highland Park Occidental campus where Charlie filmed The Kid (above left). But the stairway seemed more contemporary. The Highland Park campus was built in 1897, while the Eagle Rock campus began construction in 1912.

Click to enlarge – built in 1924, east entrance with columns left, Charlie’s north entrance right Occidental College

I logged onto Calisphere, the search platform that includes nearly every online California photo archive, to study the “new” Occidental campus, and soon zeroed in on the library as the likely candidate. Notice above the original rectangular dimensions, the east side twice as long as the north.

Preparing this post reminded me Charlie had filmed an alternate ending to Modern Times, where the Gamine, the Little Tramp’s companion portrayed by Paulette Goddard, becomes a nun, and Charlie heads out once more all alone on the open road. Their discarded farewell scene was also staged beside the Clapp Library stairs. See all 13 Chaplin Archive photos of the discarded farewell scene.

It’s fascinating to realize Charlie filmed this brief, mundane scene, requiring a simple “institutional” doorway entrance, all the way out in Eagle Rock, about 14 miles from his studio located at 1416 N. La Brea. He couldn’t find a closer set of stairs? Filming the extended alternate ending may have been a factor when choosing the site, but it still seems like a long way to go.

Numerous articles on this blog cover Charlie and Mary Pickford filming at the old Hall of Letters building at the former Highland Park campus, and the downtown factory exteriors where Charlie goes berserk in Modern Times. To learn more, please search this site, and also check out my Chaplin book Silent Traces, and the wonderful Criterion Collection Blu-ray of Modern Times, which includes my visual essay.

This link archives historic photos of the Mary Norton Clapp Library, including this view above of the north side. Charlie’s north doorway was originally flanked by twin pairs of windows. The library was extended in 1955, adding two more windows to each side of the north entrance, making the library dimensions now more “square” than rectangular. Chaplin’s doorway may have been moved or rebuilt. The large the modern extension to the right was built in 1971.

For more visual detective work, check out “Case Closed – How Buster Keaton made Sherlock Jr.” accompanied by renowned pianist and composer Michael D. Mortilla.

Check out the library on Google Maps below