John Bengtson's Blog, page 24

January 19, 2014

Buster Keaton and The Three Stooges – Round 6

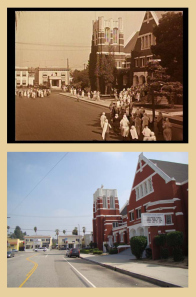

Click to enlarge. The extant Olympic Auditorium appearing in Keaton’s Battling Butler and in the Three Stooges’ Punch Drunks (1934). This is my sixth post about filming connections between Buster and the Stooges.

In his 1926 self-directed feature comedy Battling Butler, Buster plays an effete millionaire who seeks to impress a girl by allowing her to mistakenly believe he is a champion boxer sharing the same name. As might be guessed, the movie ends when amateur Buster, spurred by love and honor, defeats the pro boxer in a fight and wins the girl’s heart.

Key scenes took place in the newly opened Olympic Auditorium, still standing at 18th and Grand in downtown Los Angeles. Construction began on January 10, 1925, with world champion fighter Jack Dempsey on hand for the ceremonies, breaking ground with a steam shovel. Dempsey returned when the completed arena opened August 5, 1925, and was presented with a solid gold lifetime ticket, the size of a calling card, good for all future events at the venue. The so-called “Punch Palace” was built in preparation for the 1932 Los Angeles Olympic Games, and was the largest arena of its kind west of New York City, reportedly seating up to 15,300. The boxing and wrestling hall could be converted to host other programs, and the California Grand Opera Company performed there during October 1925.

Key scenes took place in the newly opened Olympic Auditorium, still standing at 18th and Grand in downtown Los Angeles. Construction began on January 10, 1925, with world champion fighter Jack Dempsey on hand for the ceremonies, breaking ground with a steam shovel. Dempsey returned when the completed arena opened August 5, 1925, and was presented with a solid gold lifetime ticket, the size of a calling card, good for all future events at the venue. The so-called “Punch Palace” was built in preparation for the 1932 Los Angeles Olympic Games, and was the largest arena of its kind west of New York City, reportedly seating up to 15,300. The boxing and wrestling hall could be converted to host other programs, and the California Grand Opera Company performed there during October 1925.

Buster and his valet, played by Snitz Edwards, sit stunned after witnessing a formerly obscure boxer who shares Keaton’s name unexpectedly win a championship bout.

The marquee as it appears in Punch Drunks

Because Buster started working on Battling Butler only months after the arena first opened, its role in the movie could be its debut appearance on film. Aside from appearing with the Three Stooges in Punch Drunks, the arena has been used as a location for classic films such as Rocky (1976) and Million Dollar Baby (2004). You can find my five other posts about Buster and the Stooges HERE.

Remarkably, the William Holden film noir drama The Turning Point (1952) has strong connections to all three leading silent comedy stars. The movie not only makes great use of the arena where Buster filmed (see below), it also shares noir locations on Bunker Hill with Harold Lloyd’s 1924 feature Hot Water, and in the gas tank district with Charlie Chaplin’s 1936 comedy Modern Times.

Four views of the Olympic Auditorium from The Turning Point

As I reported a while back in my column for The Keaton Chronicle, the film concludes with Buster, decked out in boxing shorts and a silk top hat, strolling down a city boulevard at night with his girl on his arm, oblivious to the curious onlookers surrounding them.

Click to enlarge. The Biltmore Hotel, designed by Schultze & Weaver in 1922, is located on Olive Street facing Pershing Square. Keaton strolled from the corner of 5th and Olive, with the San Carlos Hotel across 5th Street, which bears a “STEAMSHIP TICKETS” sign (oval) in each image. UCLA Libraries – Digital Collection.

Unlike Buster’s contemporary Harold Lloyd, Keaton seldom filmed in the downtown Los Angeles Historic Core, and locating this concluding shot eluded me for years. But once I determined that Harold had used the Olive Street entrance of the classic Los Angeles Biltmore Hotel for scenes from For Heaven’s Sake, I realized Keaton had filmed here too. The Biltmore has appeared in dozens of films.

Although usually ranked among Keaton’s lesser works, I’ve always found Battling Butler to be quite charming. The film contains many thoughtfully composed scenes, such as Buster’s fiancé framed

Although usually ranked among Keaton’s lesser works, I’ve always found Battling Butler to be quite charming. The film contains many thoughtfully composed scenes, such as Buster’s fiancé framed  through the rear window of his limousine, receding into the distance as Buster drives away, and a tracking shot of Buster and Snitz, lost in thought, sitting on the steps of a moving passenger train.

through the rear window of his limousine, receding into the distance as Buster drives away, and a tracking shot of Buster and Snitz, lost in thought, sitting on the steps of a moving passenger train.

Some other interesting visual framing devices from Battling Butler

In closing, Battling Butler also contains a clear image of Buster’s injured right index finger during a scene where he registers at a hotel. Buster trapped his finger in a clothes mangler as a young child, and had to have the tip amputated.

In closing, Battling Butler also contains a clear image of Buster’s injured right index finger during a scene where he registers at a hotel. Buster trapped his finger in a clothes mangler as a young child, and had to have the tip amputated.  This shot to the right, of “Buster” holding an engagement ring, was filmed using a hand double. It is a strange coincidence that both Buster and Harold Lloyd had injured right hands.

This shot to the right, of “Buster” holding an engagement ring, was filmed using a hand double. It is a strange coincidence that both Buster and Harold Lloyd had injured right hands.

Battling Butler (C) 1926 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Corporation. (C) renewed 1954 Loew’s, Inc. Punch Drunks copyright Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. The Turning Point (C) Paramount Pictures Corporation.

Today the Olympic Auditorium is home to a church.

View Larger Map

Filed under: Buster Keaton, Film Noir, The Turning Point, Three Stooges Tagged: Battling Butler, Boxing, Buster Keaton, film noir, film noir locations, Los Angeles Historic Core, Olympic Auditorium, Punch Drunks, Silent Comedians, Silent Comedies, Silent Movie Locations, The Turning Point, then and now, Three Stooges

January 1, 2014

Harold Lloyd Takes A Chance on Court Hill

Harold in front of 216 – 218 Hope Street Los Angeles Public Library 00091559

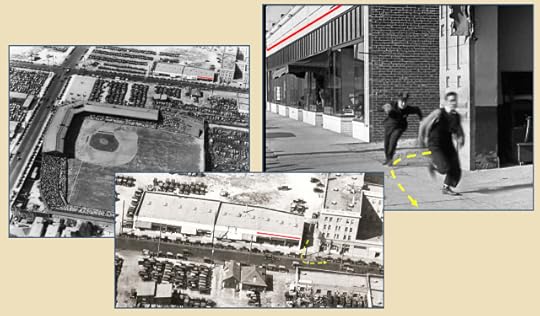

The Criterion Collection Blu-ray release of Safety Last! contains many bonus features, including three razor-sharp early Harold Lloyd short films. One such film, Take A Chance (1918) featured here, provides rare views of the long lost Court Hill neighborhood where Lloyd and producer Hal Roach began their careers.

The Criterion Collection Blu-ray release of Safety Last! contains many bonus features, including three razor-sharp early Harold Lloyd short films. One such film, Take A Chance (1918) featured here, provides rare views of the long lost Court Hill neighborhood where Lloyd and producer Hal Roach began their careers.

Harold confronts Snub Pollard driving away with Bebe Daniels in front of 216 – 218 Hope Street Los Angeles Public Library 00091449

Click to enlarge. This later aerial view shows the block of Hope Street where Lloyd filmed. USC Digital Library EXM-P-S-LOS-ANG-CIT-AIR-VIE-019. Each building can be viewed up close (see below).

Lloyd filmed along the block of Hope Street (above) between Temple Street to the left, and Court Street to the right. Each building in the above aerial view can be viewed individually at the Los Angeles Public Library Homes of N. Hope St collection, including to the left of

Court Apartments

Harold, 242 Hope St, 240 Hope St, 236 Hope St, 232 Hope St, 228 Hope St, and the three story apartment with the front balconies at 224 Hope St, and to the right of Harold, 212 – 214 Hope St, 210 Hope St, 206 Hope St, and on the corner of Hope and Court, the Court Apartments. A reverse view of the corner Court Apartments appears (right) during a scene from Lloyd’s A Gasoline Wedding (1918), filmed looking north up Court St towards Hope.

Harold turns the corner from Court onto Grand in front of the Chestmere Apartments – Watson Family Photographic Archive

Later in Take A Chance Harold chases Snub Pollard and Bebe Daniels past the Chestmere Apartments that stood on Court and Grand, just two short blocks from the Bradbury Mansion that served as the studio home for Lloyd and producer Hal Roach. The mansion stood on the corner of Hill and Court Streets, with the main entrance facing Hill.

Later in Take A Chance Harold chases Snub Pollard and Bebe Daniels past the Chestmere Apartments that stood on Court and Grand, just two short blocks from the Bradbury Mansion that served as the studio home for Lloyd and producer Hal Roach. The mansion stood on the corner of Hill and Court Streets, with the main entrance facing Hill.

The filming locations on Hope St and Grand St – USC Digital Library DW-C1-11-6-ISLA

Chestmere Apts

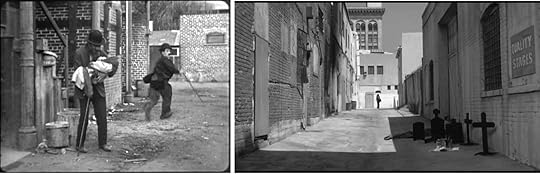

The Chestmere Apartments also appears in reverse view behind Harold in this scene (right) from one of his earliest surviving movies, Lonesome Luke Messenger (1917). The view looks north up Court Street – Lloyd’s Bradbury Mansion studio stands to the left, just out of view. Lloyd is running down Court St from the corner of Olive St. The row of homes on Court St across from the mansion, off camera to the right, appear in many early Lloyd comedies.

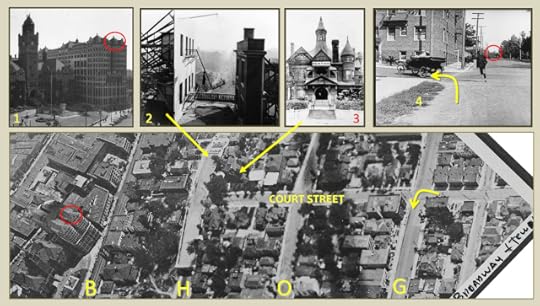

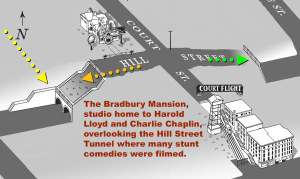

Click to enlarge. This 1919 aerial view looking south situates the Bradbury Mansion (3 – viewed from Hill St) and the Chestmere Apartments (4). The south overlook of the Hill Street Tunnel (2) is where Lloyd and many other comedians built sets to film stunt comedies. The movie frame oval (4) shows the tower of the former Hall of Records (1) on Broadway, below the base of Court Hill. Street index – (B) Broadway, (H) Hill Street, (O) Olive Street, (G) Grand Avenue. Watson Family Photographic Archive

This 1919 aerial view above shows the Court Hill filming location in relation to local landmarks, such as the Hill Street Tunnel overlook, where many stunt comedies were filmed, and Lloyd’s Bradbury Mansion studio. You can read a detailed account of this aerial photo, showing how stunt comedies were filmed, in this post LA’s early hills and tunnels preserved in comedies and film noir.

Also from Take A Chance, Harold in front of the Majestic Apartments at 406 W. Temple

Take A Chance begins with Harold flipping his last dime to decide whether to spend it eating or getting a hair cut. Instead he loses it down a storm drain. This scene was filmed in front of the Majestic Apartments on Temple St., also just steps away from the Bradbury Mansion. In this post I explain how the Majestic and the Hill Street Tunnel appear in the 1949 Burt Lancaster noir classic Criss Cross. You can see the relation of the Majestic to the other Take A Chance filming locations in the view below.

Click to enlarge. The Take A Chance filming locations; Hope Street (1), the Chestmere Apts on Court St (2), and the Majestic Apts on Temple St (4). The Bradbury Mansion filming studio, and twin bore Hill St Tunnel, appear in the box and matching Map (3) by Piet Schreuders. Street index – (G) Grand Avenue, (O) Olive Street, (H) Hill Street, (B) Broadway. Nothing of this setting, aside from the street names, remains today.

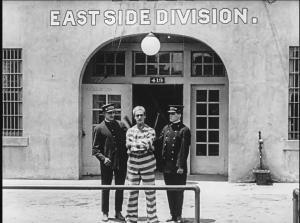

Take A Chance ends at the real life Los Angeles city jail, once located at 419 N. Ave. 19.

Take A Chance concludes with an escaped prisoner knocking Harold unconscious, and swapping their clothes. Unaware of his new appearance, Lloyd ignores these two policemen, who drag him off to jail. The setting was the true Los Angeles city jail, that appears in many early comedies, including Laurel and Hardy’s The Hoose-Gow (1928). You can read more about the jail in this post Laurel-and-Hardy-Charlie-Chaplin-four-silent-jailbreaks.

HAROLD LLOYD images and the names of Mr. Lloyd’s films are all trademarks and/or service marks of Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc. Images and movie frame images reproduced courtesy of The Harold Lloyd Trust and Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc.

Approximately 216 N. Hope St today – Google Maps

View Larger Map

Filed under: Court Hill, Hal Roach Studios, Harold Lloyd, Safety Last! Tagged: Bradbury Mansion, Court Hill, Harold Lloyd, Hill Street Tunnel, Lloyd Studio, Rolin Studio, Safety Last!, Silent Comedians, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, Take A Chance, then and now

December 2, 2013

W.C. Fields in Palm Beach – It’s the Old Army Game

W.C. Fields in Florida beside El Mirasol

For a complete change of pace, here’s a Florida location highlighting W.C. Fields. Field’s feature comedy It’s A Gift (1934) is known for many classic sequences, including the sleeping-porch scene where a pushy insurance salesman searching for “Carl La Fong” disrupts Fields’ slumber. During another scene, Fields and family take a break from their cross-country drive to share a messy picnic on the grounds of a large estate that they mistakenly presume to be a public park. By the time the estate butler chases them away the grounds are ruined and buried in trash.

For a complete change of pace, here’s a Florida location highlighting W.C. Fields. Field’s feature comedy It’s A Gift (1934) is known for many classic sequences, including the sleeping-porch scene where a pushy insurance salesman searching for “Carl La Fong” disrupts Fields’ slumber. During another scene, Fields and family take a break from their cross-country drive to share a messy picnic on the grounds of a large estate that they mistakenly presume to be a public park. By the time the estate butler chases them away the grounds are ruined and buried in trash.

The front gate to the Stotesbury estate in Palm Beach, Florida

What I did not realize is that this scene was reworked from one of Fields’ prior silent comedies It’s the Old Army Game (1926) (on YouTube) co-starring Louise Brooks, and directed by Edward Sutherland. As James Curtis reports in W. C. Fields: A Biography (Knopf, 2003), the sequence was filmed in Palm Beach, Florida at El Mirasol, the estate of Edward T. Stotesbury, “a Philadelphia banker who loved hob-nobbing” with Hollywood stars. Curtis writes that the film crew behaved irresponsibly, and trashed the immaculate front lawn facing the ocean as the servants watched in horror.

What I did not realize is that this scene was reworked from one of Fields’ prior silent comedies It’s the Old Army Game (1926) (on YouTube) co-starring Louise Brooks, and directed by Edward Sutherland. As James Curtis reports in W. C. Fields: A Biography (Knopf, 2003), the sequence was filmed in Palm Beach, Florida at El Mirasol, the estate of Edward T. Stotesbury, “a Philadelphia banker who loved hob-nobbing” with Hollywood stars. Curtis writes that the film crew behaved irresponsibly, and trashed the immaculate front lawn facing the ocean as the servants watched in horror.

Bill and family on the El Mirasol front lawn.

Described as the grandest home ever built in Palm Beach, the 37 room estate was demolished in the 1950s, and the property subdivided. You can read more about El Mirasol, Stotesbury, and his other mansions, at these links HERE and HERE.

A closer view of the estate from It’s The Old Army Game.

Filed under: Uncategorized Tagged: El Mirasol, It's a Gift, It's The Old Army Game, Louise Brooks, Palm Beach, Silent Comedians, Silent Comedies, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, Stotesbury, then and now, W.C. Fields

November 12, 2013

New City Lights Release – Discoveries and Assumptions

Here’s a new location discovery to celebrate the Criterion Collection Blu-ray release of Charlie Chaplin’s 1931 masterpiece City Lights.

The scenes where Charlie reports to work as a street sweeper, and where he also learns there is money to be made in the boxing ring, were filmed on the Chaplin Studio backlot beside the open parking stalls of the studio garage.

The scenes where Charlie reports to work as a street sweeper, and where he also learns there is money to be made in the boxing ring, were filmed on the Chaplin Studio backlot beside the open parking stalls of the studio garage.

I knew that these scenes had to have been filmed at the studio, but for years my false assumption that they were filmed looking north prevented the geometry from falling into place to reveal the location. Once I “thought outside the box” long enough to question whether the scenes might have been filmed looking east instead of north, I immediately solved the puzzle.

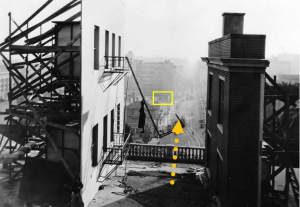

Click to enlarge – looking west across the Chaplin Studio backlot. The arrow (pointing east) marks the studio garage, used as the street sweeper work station in City Lights. The French village set (dotted line) appears in A Woman of Paris.

While there is scant photographic record of the non-glamorous motor-pool corner of Chaplin’s backlot, the studio garage appears to the left in this panoramic image above, taken in 1923, looking west across the lot towards the entrance gate on La Brea, and the French village set constructed for Chaplin’s dramatic feature A Woman of Paris.

Click to enlarge – the arrow points east towards the Chaplin Studio carpenter shop. The boxing gym is a very simplistic corner set.

As shown above, the Chaplin Studio carpenter shop appears in the background of the scenes from City Lights. The close-up view of the shop, lower left above, comes from How to Make Movies (1918), the documentary footage Chaplin shot of his studio that he had hoped to submit to his distributor First National as a theatrical release in lieu of an actual comedy. The carpenter shop still stands in place on the lot today.

Click to enlarge – this circa 1930 view looks east towards several Chaplin Studio landmarks. Marc Wanamaker – Bison Archives.

The above aerial view, looking east at the Chaplin Studio located at 1416 N. La Brea, shows from left to right (i) the site of the flower shop set on the backlot, where the emotionally charged final scene was filmed, (ii) the location of the studio garage, and (iii) the open air stage where Chaplin filmed the Little Tramp’s first encounter with the blind Flower Girl.

Click to enlarge – the sweeper set stood behind the statues set

An even closer look (above) reveals that the sweeper work station set stood immediately behind the civic park statues set.

Click to enlarge – Marc Wanamaker – Bison Archives

The City Light street sets

The above circa 1928 view of the Chaplin Studio, looking to the NE, shows that Chaplin had already painted the large civic backdrop mural that appears during the scene where the Little Tramp meets the Flower Girl. It is clear from the above photo that by 1928 Chaplin had yet to build the elaborate city street backlot set (right) that appears so frequently during the film. Chaplin would use this backlot set again extensively in Modern Times (1936) and The Great Dictator (1940).

As mentioned, I would have found the above street sweeper work station scenes from City Lights much sooner if I had not mistakenly assumed the shots were filmed looking north. But identifying non-obvious movie locations requires making such basic assumptions regarding the position of the camera. For example, I was able to solve the location of the church from Buster Keaton’s 1925 feature Seven Chances (left) only by first correctly assuming the camera view looked north. In turn, this meant that the church stood on the SE corner of a “T” intersection, which proved to be the unique key to solving the mystery.

It’s easy to get tripped up identifying spots assuming east is always east and west is always west. There is no film-makers’ oath requiring cinematic landscapes filmed on location to comport with reality. Movies frequently match scenes filmed miles apart, or traveling in opposite directions. So both in life, and in silent movie location identification (you know, the important things)  , it always pays not to assume too much and to keep an open mind – you never know what you might find.

, it always pays not to assume too much and to keep an open mind – you never know what you might find.

You can read all about how Chaplin filmed City Lights in my book Silent Traces. There’s also a fun City Lights post about the Little Tramp finding a cigar butt beside the Beverly Wilshire Hotel HERE.

You can read all about how Chaplin filmed City Lights in my book Silent Traces. There’s also a fun City Lights post about the Little Tramp finding a cigar butt beside the Beverly Wilshire Hotel HERE.

Seven Chances licensed by Douris UK, Ltd. All images from Chaplin films made from 1918 onwards, copyright © Roy Export Company Establishment. CHARLES CHAPLIN, CHAPLIN, and the LITTLE TRAMP, photographs from and the names of Mr. Chaplin’s films are trademarks and/or service marks of Bubbles Incorporated SA and/or Roy Export Company Establishment. Used with permission.

Filed under: Chaplin Studio, Charlie Chaplin, City Lights Tagged: Chaplin Locations, Chaplin Studio, Charlie Chaplin, City Lights, Hollywood, Silent Comedians, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, then and now

October 30, 2013

LA’s Early Hills, Tunnels Preserved in Noir – Silent Comedies

TWO HILLS – THREE TUNNEL PORTALS – ONE PHOTO – CLICK TO ENLARGE – we’ll cover each image one at a time below. Looking SE at the Civic Center and Court Hill (1919) – Watson Family Photographic Archive

Once marked with hills and tunnels, the complicated landscape of early Los Angeles has changed so dramatically that it’s difficult to visualize how all of the pieces once fit together. Massive landmarks such as Court Hill and the Broadway Tunnel were bulldozed into oblivion. In fact, not a single hill, tunnel, or even building in the above photo still exists.

Using a remarkable 1919 aerial photo from the Watson Family Photographic Archive, several “stunt” climbing silent comedies for detail, and a noir classic for good measure, this post deconstructs how early filmmakers exploited LA’s unique topography, and how such films provide an invaluable window to the past.

Click to enlarge – Bobby Dunn in No Danger (1923). The arrow points from above the Broadway Tunnel past the roof line of the Alhambra Hotel (box), past the County Court House (1), the Hall of Records (2), and the crenelated clock tower (oval) of the Los Angeles Time Building at 1st and Broadway (3).

We begin (above) looking south from above the Broadway Tunnel towards the County Court House (1), the Hall of Records (2), and the Los Angeles Times Building (3) as seen in Bobby Dunn’s stunt-climbing short comedy No Danger, posted on YouTube.

The aerial view at right looks north up Broadway from the LA Times Clock Tower (oval) toward the Broadway Tunnel overlook where the movie was filmed. LAPL.

Some prominent landmarks appearing in No Danger include the rooftop signs of the former Alhambra Hotel and Hotel Alhambra Apartments, that stood facing each other on opposite sides of Broadway.

Reversing the No Danger movie frame reveals the rooftop signs marked to the right.

In 1923 the Alhambra Hotel was moved north up Broadway 122 feet towards the face of the Broadway Tunnel to make room for the Hall of Justice, shown here in 1924 under construction, and completed in 1925. The right box in the photo to the left (LAPL) shows the hotel’s original position, and the left box shows the hotel after the move. Separated by Temple Street from the County Court House (1) and the Hall of Records (2), the Hall of Justice is the only building appearing in this photo that remains standing.

In 1923 the Alhambra Hotel was moved north up Broadway 122 feet towards the face of the Broadway Tunnel to make room for the Hall of Justice, shown here in 1924 under construction, and completed in 1925. The right box in the photo to the left (LAPL) shows the hotel’s original position, and the left box shows the hotel after the move. Separated by Temple Street from the County Court House (1) and the Hall of Records (2), the Hall of Justice is the only building appearing in this photo that remains standing.

The Kress House Moving Company (red box) was awarded a $63,770 contract to move the massive Alhambra Hotel 122 feet further north up Broadway from Temple. It appears No Danger was filmed before the move began. The upper right photo shows the dozens of parallel train tracks positioned to move the hotel towards the camera. The yellow box marks the former Broadway Hotel. USC Digital Library.

A set from The Terror Trail (1921) overlooking the Hill Street Tunnel – Marc Wanamaker Bison Archives

The next image (below) comes from Harold Lloyd’s 1921 thrill comedy Never Weaken, filmed on Court Hill above the Hill Street Tunnel, looking south down Hill Street from a set similar to the one depicted to the left. The Hotel La Cross at 122 S. Hill Street (yellow box left and below) is a conspicuous landmark that is readily spotted in nearly all movies filmed above the Hill Street Tunnel. In the second half of a prior post, fully annotated with photos and maps, I explain all about how Lloyd, Charlie Chaplin, and other comedians filmed at the Bradbury Mansion Studio atop Court Hill, and made use of the Hill Street Tunnel overlook.

Harold Lloyd in Never Weaken. The arrow points south down Hill Street, from the balustrade overlooking stepped terraces leading to the tunnel portal – the yellow box marks the sign for the Hotel La Crosse. The oval marks the Bradbury Mansion, an elaborate home at the corner of Court Street and Hill Street, later used as a silent movie studio by Charlie Chaplin, Hal Roach, and Harold Lloyd.

This map (left – click to enlarge) by Piet Schreuders looks north towards Court Hill, and shows the short length of the Hill Street Tunnel relative to the Bradbury Mansion and the Court Flight incline railway. Dozens of movies were filmed overlooking the tunnel (orange arrow), but for variety, a few movies were filmed nearby. The yellow arrow points south from bare land on the hilltop, from which the next image below was taken.

This map (left – click to enlarge) by Piet Schreuders looks north towards Court Hill, and shows the short length of the Hill Street Tunnel relative to the Bradbury Mansion and the Court Flight incline railway. Dozens of movies were filmed overlooking the tunnel (orange arrow), but for variety, a few movies were filmed nearby. The yellow arrow points south from bare land on the hilltop, from which the next image below was taken.

This stunt scene featuring Clyde Cook in the Hal Roach Studio short film Should Sailors Marry? (1925) was filmed looking east down 1st Street from Court Hill towards the Los Angeles Times Building clock tower (oval) at 1st and Broadway.

The north end of the Hill Street Tunnel commanded less of a view, and seems to have appeared in far fewer films than did the southern end of the tunnel overlooking downtown. However, the north end of the tunnel and Court Hill play a major role in the film noir classic Criss Cross (1949) starring Burt Lancaster and Yvonne De Carlo (see below). For a detailed report of these landmarks as they appear in Criss Cross, check out my post HERE.

Burt Lancaster in Criss Cross - behind him, the north portal of the Hill Street Tunnel.

Both images below depict the block bounded by Broadway, 1st Street, Hill Street, and Temple, yet aside from the street layout and names, these two images share NOTHING in common. The hills, tunnels, buildings, and even certain streets, such as New High and Court Street, are forever gone, preserved only in vintage photos, … and in the movies.

(C) 2013 Nokia Image courtesy of LAR – IAC (C) 2103 Microsoft Corporation Pictometry Bird’s Eye (C) 2012 Pictometry International Corp.

HAROLD LLOYD images and the names of Mr. Lloyd’s films are all trademarks and/or service marks of Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc. Images and movie frame images reproduced courtesy of The Harold Lloyd Trust and Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc. Criss Cross (C) 1948 Universal Pictures Company. Should Sailors Marry? licensed from Lobster Films (C) 2005 Lobster Films.

Filed under: Court Hill, Film Noir, Lloyd Thrill Pictures, Los Angeles Historic Core Tagged: Alhambra Hotel, Bobby Dunn, Broadway Tunnel, Clyde Cook, Court Hill, Criss Cross, film noir locations, Hal Roach, Hal Roach Studios, Harold Lloyd, Hill Street Tunnel, Kress House Moving Company, Lloyd Thrill Pictures, Los Angeles Civic Center, Los Angeles Historic Core, Never Weaken, Silent Comedians, Silent Comedies, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, then and now

October 23, 2013

More Discoveries From Keaton’s Cops

Click to enlarge – Buster flees from the Rutland Apartments (box) at 1839 S Main

Buster Keaton’s best-known short film Cops (1922) has always been one of my favorite movies. I must have been twelve when I first bought an 8mm print of it, and have since watched it dozens of times. Now that it is available on Blu-ray, Cops continues to reveal fascinating details about early Los Angeles and Keaton’s working methods.

Riding past Gower

One thing that struck me is that Cops does not contain a single interior scene. Except for the reaction shots of Joe Roberts discovering his wallet and cash are missing (filmed on location within a taxicab traveling east down Santa Monica past Gower, just blocks from the Keaton Studio), every scene in the movie is filmed out of doors. I made a mental list, and every other movie Keaton produced at his studio contains at least one interior scene filmed on an indoor stage.

The covered stage

At some point during 1921 the open-air filming stage at the Keaton Studio was converted into a large barn-shaped enclosure. Although this construction likely took place earlier in the year, it is fun to imagine that Cops, filmed during December 1921, was deliberately structured without any interior scenes in order to provide the studio carpenters sufficient leeway to complete their work.

The yellow car Los Angeles Railway MONETA AVE line ran south to Manchester

The scene depicted above was filmed far away from downtown, 19 blocks south of the Los Angeles Civic Center, as an angry cop chases Buster from an alley into a busy intersection, and Buster then knocks down a traffic cop to trip the first cop chasing him. The clue to this discovery is the trolley car approaching in the background during the scene (left) that clearly reads “MONETA AVE.” on the destination sign. While there is still a Moneta Avenue today much further south from downtown, the Los Angeles street layout was significantly different back when Keaton was filming in 1922.

Broadway originally ended near 10th Street (now Olympic) by merging into Main Street, but was later extended a few blocks further south to terminate at Pico. Main continued southwest until 36th Street, where it split into Moneta Avenue and Main, parallel streets both heading due south. Today Broadway has been extended much further southwest, hooking up with what was Moneta, and today most of Moneta is re-named Broadway. Simple, huh? I knew that Keaton filmed other scenes from Cops south of 11th Street, and found this location simply by using Google Street View. Although I started on Broadway, I followed the trolley route south onto Main, and somehow was patient enough to continue for several more blocks until I got lucky and recognized the setting.

Buster knocked the cop down at the intersection of Main and Washington Boulevard, with the camera looking towards the NW corner up Main. The prominent awning in the background, remarkably still attached considering the earthquake risk, belongs to the Rutland Apartments at 1839 S. Main (see color view at top of post). Other prominent buildings in the background are still standing as well.

Buster knocked the cop down at the intersection of Main and Washington Boulevard, with the camera looking towards the NW corner up Main. The prominent awning in the background, remarkably still attached considering the earthquake risk, belongs to the Rutland Apartments at 1839 S. Main (see color view at top of post). Other prominent buildings in the background are still standing as well.

After reporting this discovery to “Skip,” the publicity-shy, eagle-eyed sleuth who discovered the “Solved at Last” mystery building from Safety Last!, Skip quickly reported back that the preceding scene with Buster and the alley was filmed on the Washington side of the very same Rutland Apartment building – a rare instance where the cinematic geography for these two scenes comports with reality. Skip had noticed that the wall details in both scenes matched, and correctly surmised it was the same building. Although these two scenes could have been filmed at almost any urban intersection, for some reason Keaton chose to film here, roughly 150 blocks away from his studio.

After reporting this discovery to “Skip,” the publicity-shy, eagle-eyed sleuth who discovered the “Solved at Last” mystery building from Safety Last!, Skip quickly reported back that the preceding scene with Buster and the alley was filmed on the Washington side of the very same Rutland Apartment building – a rare instance where the cinematic geography for these two scenes comports with reality. Skip had noticed that the wall details in both scenes matched, and correctly surmised it was the same building. Although these two scenes could have been filmed at almost any urban intersection, for some reason Keaton chose to film here, roughly 150 blocks away from his studio.

Looking west down Washington – the oval marks matching details that Skip noticed in the prior shot.

Once I got over the shock that these two 91-year-old locations still existed, remarkably unchanged, it dawned on me that this intersection was just across the street from the former Washington Park baseball field. The park was the former home to both the Los Angeles Angels and the Vernon/Venice Tigers, from 1911, when the park was built, until the first few games of the 1925 season, when play moved to the recently opened Wrigley Field at Avalon Boulevard and 41st Street. Demolished in 1926, Washington Park once stood on the former grounds of Chutes Park, an early amusement center where patrons plunged a boat down a steep ramp into a pool.

Washington Park Los Angeles Public Library as it appeared in Neighbors

A cop beaned by the Babe

I mention this because it turns out Keaton had been in this neighborhood previously to film ballpark scenes for his 1920 short comedy Neighbors. The joke in that film, such as it is, is that the cop intending to arrest Buster gets conked on the head by a home run supposedly hit out of the park by Babe Ruth. So Buster had likely encountered the intersection of Washington and Main before in 1920, but it still does not explain why he returned here to film the above scenes for Cops.

Click to enlarge – the alley on Washington appearing in Cops stood across from the park

?? Based on the number of extras and the quality of the set – this is likely the Goldwyn backlot

Another intriguing aspect of Cops is that with the additional clues visible in its high definition release, and the ever-increasing availability of vintage photographs and online resources, I have been able to identify every location from the movie. Further, I have been able to identify which studio backlots were used for all but for two scenes filmed on exterior sets. This means that except for these two sets (depicted here), I can now identify every single scene in the entire movie, including every shot of the policeman’s day parade filmed in New York. I’ve already posted several new discoveries here, including the scene filmed on the roof of Musso & Frank in Hollywood, and the teeter-totter fence scene filmed at the current-day site of Paramount Studios, but it may take years to cover them all.

?? Based on fewer extras, the set design, and the late day sunlight – this is likely the Metro backlot

In closing, my intimate understanding of Cops only reinforces the tremendous respect I have for Keaton, his crew, and for all of the other hard-working silent comedy filmmakers. Imagine the advance planning and logistics involved simply in capturing each of the scenes with Buster’s horse-drawn wagon load of furniture. The horse and moving wagon were transported all over town to film at nine different places; namely, in Hollywood at Cosmo and Selma, Santa Monica and Vine, on the Metro Studio backlot at Lillian Way and Romaine, and at the Brunton Studio backlot at Melrose and Windsor; then in Skid Row, on Arcadia near the Plaza de Los Angeles, and at Ducommun and Alameda; then south of downtown by Santee Alley and Olympic, and by 11th and  Main; and then finally way out at the Goldwyn Studios backlot in Culver City. That’s nine widely dispersed locations just for the poor horse! Add to that the dozens of other individual scenes that comprise Cops, and you can appreciate what a remarkable feat it was creating this historic film.

Main; and then finally way out at the Goldwyn Studios backlot in Culver City. That’s nine widely dispersed locations just for the poor horse! Add to that the dozens of other individual scenes that comprise Cops, and you can appreciate what a remarkable feat it was creating this historic film.

Cops and Neighbors licensed by Douris UK, Ltd. Color images (C) 2013 Google.

View Larger Map

Filed under: Bunker Hill, Cops, Los Angeles Historic Core Tagged: Broadway, Buster Keaton, Cops, Los Angeles Historic Core, Main Street, Moneta, Neighbors, Rutland, Silent Comedians, Silent Comedies, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, then and now, Washington Park

September 8, 2013

Johnny Depp and Buster Keaton at the Cops/Ed Wood alley

Cops (1922) looking north and Ed Wood (1994) looking south – the Ed Wood image is reversed for comparison

Cosmo Street 1997

To go with the Hollywood’s Silent Echoes presentation I gave last month at the Cinecon 49 Classic Film Festival at the Egyptian Theater, I prepared a tour of nearly 50 silent-era Hollywood landmarks and film locations you can access HERE. During the lunch break I lead a group of 40 or so hearty souls a few blocks east from the theater to the 1700 block of Cahuenga, where we braved the extreme heat to explore many places where Chaplin, Keaton, Fairbanks, and Lloyd filmed scenes from their classic movies.

The Kid

The tour ended at the north end of East Cahuenga Alley (that the locals call “EaCa Alley”), running parallel between Cahuenga and Cosmo, where Charlie Chaplin filmed early scenes from The Kid (1921), Buster Keaton filmed Cops (1922), and Harold Lloyd filmed Safety Last! (1923). The three great comedians, and three iconic masterpieces each inducted into the National Film Registry, all filmed at the same spot, a 6-in-1 location described in my post HERE. If one spot in Hollywood deserves a star of recognition, this would be it.

Johnny Depp channels Buster in Benny and Joon

During the tour, someone correctly mentioned that the same alley had appeared in the 1994 Tim Burton/Johnny Depp eponymous biopic Ed Wood. Depp had won accolades the prior year for playing a free-spirited character, inspired by Keaton and Chaplin, in the 1993 comedy/drama Benny and Joon. As shown above, Keaton and Depp both filmed exterior scenes at the same Cosmo Street location in Hollywood seventy years apart. (To aid with the comparison I reversed the Depp scene, which was filmed looking south, to match the Keaton scene filmed looking north.)

Looking west or northwest at a matching corner post in Keaton’s Neighbors (1920) and in Ed Wood.

During another scene in Ed Wood frustrated actress Vampira (played by Lisa Marie) exits a bus at the north end of EaCa Alley looking for Mr. Wood’s studio. Above, the extant iron post and steel beam supporting the back corner of 1644 N. Cahuenga appears both in Buster’s earlier short Neighbors and in Vampira’s close-up. The corner (left) is now part of the Spice Hollywood Bistro, that features patio dining where the great comedians once filmed. Below, Chaplin runs north up EaCa Alley towards the same Spice corner – his position is nearly identical to Vampira’s placement in the alley below.

During another scene in Ed Wood frustrated actress Vampira (played by Lisa Marie) exits a bus at the north end of EaCa Alley looking for Mr. Wood’s studio. Above, the extant iron post and steel beam supporting the back corner of 1644 N. Cahuenga appears both in Buster’s earlier short Neighbors and in Vampira’s close-up. The corner (left) is now part of the Spice Hollywood Bistro, that features patio dining where the great comedians once filmed. Below, Chaplin runs north up EaCa Alley towards the same Spice corner – his position is nearly identical to Vampira’s placement in the alley below.

Matching views looking north up EaCa Alley from The Kid and Ed Wood. Chaplin and Vampira are in essentially the same spot.

Long ignored, EaCa Alley is now a bustling center of restaurants, clubs, and weekend markets selling spices and fresh produce.

Looking south from the north end of EaCa Alley – the Spice corner post (oval) is blocked in the Chaplin view

Below, the south entrance to EaCa Alley.

The EaCa Alley south entrance

The farmer’s market at Cosmo Street today

Ed Wood contains many Hollywood scenes filmed on location, including shots of the Musso and Frank Grill (6667 Hollywood Blvd.) and Boardners (1652 N. Cherokee Ave.)

You can read how Chaplin, Keaton, and Lloyd each filmed a masterpiece at the north end of EaCa Alley at this post HERE.

Ed Wood Touchstone Pictures. Cops and Neighbors licensed by Douris UK, Ltd. All images from Chaplin films made from 1918 onwards, copyright © Roy Export Company Establishment. CHARLES CHAPLIN, CHAPLIN, and the LITTLE TRAMP, photographs from and the names of Mr. Chaplin’s films are trademarks and/or service marks of Bubbles Incorporated SA and/or Roy Export Company Establishment. Used with permission.

Filed under: Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, Cops, Hollywood Tour, The Kid Tagged: Benny and Joon, Buster Keaton, Chaplin Tour, Charlie Chaplin, Cops, EaCa, East Cahuenga Alley, Ed Wood, Hollywood, Hollywood Tour, Johnny Depp, Keaton Locations, Keaton Tour, Silent Comedies, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, then and now, Tim Burton

September 5, 2013

Harry Langdon – The Strong Man Part 3

Click to enlarge – scenes from Harry Langdon’s The Strong Man filmed along Wilshire Boulevard.

Click to enlarge – the SE corner of Wilshire Boulevard (at left) and Vermont Avenue (at right), in 1928 and partially demolished in 2002. The remaining corner buildings were demolished in 2007. A massive twin-tower condominium project is nearing completion on the site today.

Harry Langdon’s 1926 comedy feature The Strong Man contains many exterior scenes filmed in the Korea Town area of Los Angeles near Wilshire and MacArthur Park. Harry plays a WWI veteran who returns to the States hoping to meet his faithful pen-pal, Mary Brown, whose letters encouraged him during the war. True to Harry’s infant-like persona, Harry naively asks the doorman at a busy hotel (supposedly in Manhattan) if he knows Mary Brown. Playing along, the doorman tells Harry “sure I know Mary – she passes by that nearby corner every day.” Waiting at the corner, Harry soon meets an unscrupulous woman, played by Gertrude Astor, who pretends to be Mary in order to hide a wad of stolen cash in Harry’s coat before she is searched by a suspicious police detective.

Click to enlarge – Harry meets the doorman by the former entryway to 3142 Wilshire Boulevard, just steps from the corner of Shatto Place. The red box marks the showroom window of the Rolls Royce auto dealership that once operated at the corner storefront. USC Digital Library

Harry shows the doorman Mary’s photo

The scenes with the doorman, “Mary,” and the detective, were all filmed along the commercial building that once stood on the south side of Wilshire Boulevard, between Vermont Avenue to the west, and Shatto Place to the east. Many of these shots are identified at the top of this post. As depicted here, the doorman tells Harry to wait for Mary at the corner of Shatto Place, just a few steps to the left from where they are standing at 3142 Wilshire.

Harry waits for Mary at a different corner, the SW corner of Carondelet and W 7th (see Part 2 of my post)

Although the doorman and Harry were filmed just steps away from the corner of Shatto Place, Harry is filmed waiting for Mary at the corner of a similar but different building at Carondelet and W. 7th Street a few blocks away. Perhaps director Frank Capra thought seeing a Rolls Royce window sign in the background of the Shatto Place corner would be too distracting, and so filmed at a more generic setting instead. Thankfully the corner where Harry does wait for Mary still survives (directly above) and comprises my second post about The Strong Man.

Harry and “Mary” stroll west along Wilshire from Shatto Place towards Vermont – 1926 and 2002.

I also discovered that Harold Lloyd filmed many scenes from For Heaven’s Sake (1926) nearby on Shatto Place, around the corner from Wilshire, the same setting where the opening credits for the Punky Brewster television show were filmed in 1984, as both described in this post HERE.

The former Shatto Place storefronts at Wilshire, now site of a huge condominium project. Harry filmed on Wilshire along the yellow line. The corner was originally a Rolls Royce dealership (see far above). The red box on Shatto stands north of the camera shop appearing in the opening credits to the Punky Brewster TV show (right).

Looking north – Harry filmed walking west along Wilshire (yellow arrow) toward Vermont. Harold Lloyd filmed For Heaven’s Sake traveling north up Shatto Place (red arrow). Punky Brewster also filmed on Shatto.

The discoveries reported here are bittersweet, because the once-beautiful building on Wilshire was already half-demolished the first time I visited the site early in 2002, and fully demolished soon thereafter. I took what photos I could at the time, not knowing how or whether I would ever be able to use them later on. This comparison shot below is nearly meaningless, as there appear to be no remaining matching elements between the 1926 and 2002 images.

This post only became possible after I discovered some wonderful vintage photos at the USC Digital Library that allowed me to visually match the various shots in the movie. Once again we see how Los Angeles history is preserved in classic movies of the past.

The SE corner of Wilshire and Vermont in 1928. USC Digital Library

The same corner in 1934 – USC Digital Library

A similar 2013 view of the SE corner of Wilshire and Vermont. LA.CURBED

You can read about how “Mary” attempts to lure Harry into her apartment, in order to retrieve her cash, in my original post about The Strong Man, HERE.

As shown on Google Street View below, the demolished lot on Wilshire and Vermont remained vacant well into 2011, but a twin-tower high-rise condominium on the site is rapidly nearing completion.

View Larger Map

The Strong Man (C) 1926 First National Pictures, Inc., (C) renewed 1954 Warner Brothers Pictures, Inc.

Filed under: Harry Langdon, The Strong Man Tagged: Harry Langdon, Shatto Place, Silent Comedians, Silent Comedies, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, The Strong Man, then and now, Wilshire Boulevard

August 23, 2013

A new version of Keaton’s The Blacksmith – part 3, Robin Hood’s castle and more surprises

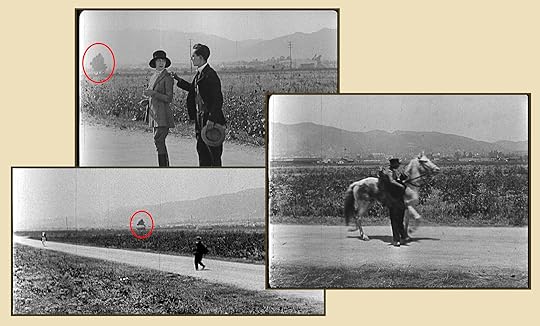

Google Earth and The Blacksmith, looking north towards Hollywood from the once wide open spaces near Melrose and Las Palmas – (C) 2013 Google

As reported in Variety, and in my first and second posts, film historian Fernando Pena has discovered that a completely different version of Buster Keaton’s 1922 short The Blacksmith circulated overseas, containing unique scenes that do not appear in the “traditional” version known to US audiences. My first post shows how the new footage provides a rare view of Keaton’s own studio, and my second post, based on visual clues, shows Keaton took a break of several months during the film’s production.

An equestrienne equipped with a shock absorber rides east down Melrose past the Hollywood Metropolitan Studios, still a studio site today, located along Santa Monica Boulevard at Las Palmas. Harold Lloyd operated as an independent producer from this studio beginning in 1924. This 1921 movie frame appears in the Kino-Lorber version of the film. hollywoodphotographs.com

My second post also shows how different versions of the film contain similar scenes filmed from different viewpoints. During the movie, Buster equips an equestrienne’s saddle with a truck shock absorber. Later in the film we see a panning shot of her struggling with her ride. The Kino-Lorber Blu-ray version of this panning shot (above) looks north as she rides east down Melrose near Las Palmas. Visual clues tell us this panning shot was filmed in 1921.

Looking SW from the Hollywood Metropolitan Studio towards the “La Brea” barn that appears in the Eureka Video Masters of Cinema version of The Blacksmith (right). Marc Wanamaker – Bison Archives

The Kino-Lorber shot

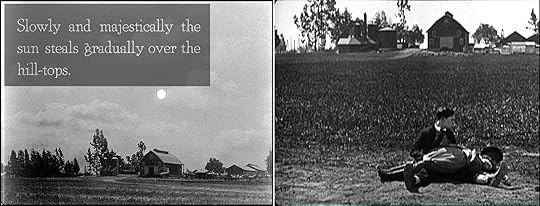

Keaton filmed many outdoor scenes from The Blacksmith near the still undeveloped intersection of Melrose and Highland. The above photo looks SW from the Hollywood Metropolitan Studio towards what I’ll call the “La Brea barn,” a classically proportioned barn that stood south of the SW corner of Melrose and La Brea. When Buster rescues Virginia Fox from a runaway horse, the La Brea barn appears behind them as they fall to the ground (above) in the Eureka Video Masters of Cinema version of the film (in the Kino-Lorber version (at left) Buster and Virgina fall into a haystack – confusing isn’t it?)

The La Brea barn also appears in this joke sunrise shot from The Scarecrow (left) as well as in the Eureka version of The Blacksmith right.

Keaton filmed the La Brea barn previously for a cartoonish joke of the rising sun popping up from the horizon introducing his 1920 short The Scarecrow.

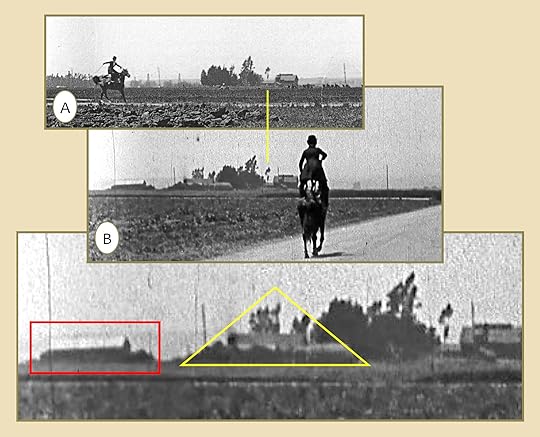

At top, 1921, riding east along Melrose looking north (Kino-Lorber); immediately above, 1922, looking west, riding north up Highland past the La Brea barn and a landmark tree towards the Robin Hood set (Eureka).

The paired images above show two similar and ordinary panning shots of the troubled equestrienne appearing in different versions of the film. Filmed in 1921, the upper scene above appears in the Kino-Lorber version; the lower scene above, filmed in 1922, appears in the Eureka version. I don’t know why Keaton bothered refilming this unremarkable shot, but he could not have recreated the 1921 shot (riding east along Melrose) in 1922, because by that time so many homes and bungalows had been built between Melrose and the studio that the scene would have looked less “rustic.”

1921 – Buster rescues Virginia from her runaway horse. In the upper left two-shot image Buster touches Virginia’s shoulder before proposing to her, a scene unique to the Kino-Lorber version. The oval marks a prominent landmark tree NW of La Brea and Melrose.

The three scenes above were filmed in 1921. The upper left two-shot, where Buster taps Virginia’s shoulder, is unique to the Kino-Lorber version.

Click to enlarge. The two-shot of Virginia and Buster was filmed (heart) on Melrose east of Highland, looking west toward the landmark tree (oval). In the aerial view the once open-air Keaton Studio stage is now covered; the Robin Hood castle set has not yet been built at the Pickford-Fairbanks Studio. hollywoodphotographs.com

This complicated image above compares the two-shot of Buster and Virginia filmed in 1921, unique to the Kino-Lorber version, and the panning shot of the equestrienne, appearing only in the Eureka version, filmed in 1922, as the rider travels north up Highland (arrow) past the La Brea barn (triangle) and the landmark tree (oval). The aerial view places the shots relative to the nearby studios.

The far right (north) end of the 1922 equestrienne panning shot reveals the massive castle set built on the Pickford-Fairbanks Studio for the 1922 release Robin Hood. The yellow line above underscores the same group of tall tents. Upper right, the set, completed with a matte painting, as it appears in Robin Hood.

The far right end of the 1922 panning shot of the equestrienne riding north up Highland (two images above) provides a brief glimpse of the castle set built in 1922 for the Douglas Fairbanks production of Robin Hood.

The 1921 two-shot of Virgina and Buster shows the Pickford-Fairbanks Studio stage (red arrow) before the Robin Hood castle set was built in 1922.

The two-shot above appears only in the Kino-Lorber version. Filmed in 1921, it shows the Pickford-Fairbanks Studio at back before the Robin Hood castle set was built there in 1922.

Scene (A) appears on the Eureka version, Scene (B ) appears as a supplement to the Kino-Lorber version. Both views look west towards the La Brea barn. The buildings and trees within the box and triangle were demolished during the many months that passed between the two takes.

Above, the equestrienne rides north up Highland in (A) and rides west on Melrose towards Highland in (B) in this pair of shots filmed looking west towards the La Brea barn. Neither shot appears in the Kino-Lorber version. Scene (A) was filmed in 1922, as the north end of the panning shot reveals the Robin Hood castle set in the background. Scene (B) was filmed in 1921, before all of the trees and buildings near the La Brea barn (within the box and triangle above) were demolished.

Click to enlarge. Looking north towards Hollywood. The oval marks the landmark tree, the arrows mark the two panning shots of the equestrienne’s path north up Highland and east along Melrose. Los Angeles Public Library

This part 3 post reveals Buster filmed scenes for The Blacksmith both before and after the Robin Hood castle set was built at the Pickford-Fairbanks Studio (Robin Hood began production in March 1922). My second post shows that a substantial amount of construction also took place near Highland between the time Keaton filmed scenes at the same spot (in the background an oil company expands from two tanks to three, and a lumber company building is extended). The aerial view above and detail view below show that the oil tank and lumber company construction was completed before the Robin Hood castle set was built. This means Buster could have filmed exteriors on three occasions; (i) the original early shots, (ii) shots after the Highland construction, but before the castle set was built, and (iii) later shots after the castle set was built.

This view was taken after the oil company added a third tank (oval) and the lumber company expanded (box), but before the Robin Hood castle set was built.

This detail from the same aerial image shows the landmark tree (oval) and the south face of the La Brea barn. Construction of the Robin Hood castle set has yet to commence.

While we may not be able to determine precisely when Keaton filmed the various exterior scenes for The Blacksmith, the visual evidence shown here and in my second post establishes that the earliest and latest scenes were filmed perhaps nine months or more apart.

Kino-Lorber movie frames licensed by Douris UK, Ltd.; Eureka movie frame licensed Lobster Films, Paris.

The NW corner of Melrose and Higland today.

View Larger Map

Filed under: Buster Keaton, The Blacksmith Tagged: Buster Keaton, Douglas Fairbanks, Fernando Pena, Fritz Lang, Hollywood, Lloyd Studio, Metropolis, Pickford - Fairbanks Studio, Robin Hood, Silent Comedians, Silent Comedies, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, The Blacksmith, then and now, Variety

August 16, 2013

Leave it to Santa Monica – Beaver and Harold Lloyd

Skokie Illinois stands in for Mayfield

Although Leave it to Beaver takes place in “Mayfield,” set in an undetermined state, I show in a prior post how Skokie, Illinois stood in for Mayfield during a scene from “Beaver’s Fortune” (Season 3: Episode 10; first broadcast December 5, 1959). While Beaver owns a surf board late in the series, and the gang makes trips to the beach, the show frequently distinguishes the Cleaver’s home state from California, often referred to as a faraway place.

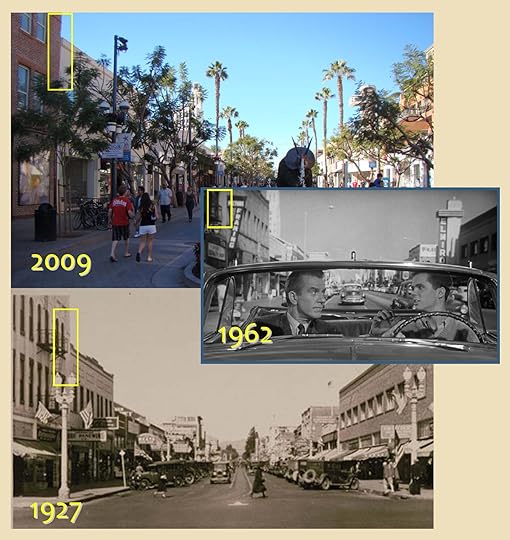

By the 6th and final season, the producers seem to have gotten tired of playing coy. When Wally and Ward take a test drive (“Wally Buys a Car; Season 6:, Episode 16, first broadcast January 10, 1963), they drive right down 3rd Street in Santa Monica, past the El Miro Theater to the right. At left in the back stands the Clock Tower Building on Santa Monica Boulevard at 3rd. The El Miro facade has been preserved as part of the multiplex theater standing there today.

California cruisin’ – Ward and Wally heading south down 3rd Street in Santa Monica. Clock Tower – Santa Monica Public Library – El Miro – Water and Power Associates

As the scene along 3rd Street ends, the north side of the Keller Building comes into view. You can glimpse it to the left (yellow box) in each image below.

Looking north up 3rd Street from Broadway. Absent in the 1927 view are the Clock Tower (left) built in 1929, and the El Miro tower (right) built in 1933. The yellow box marks the transition from the historic Keller Building on the corner of Broadway and the two-story building north of it. Closed to street traffic today, the site is now known as the Third Street Promenade. Santa Monica Public Library

In another post, I show how Beaver and Harold Lloyd both filmed scenes at the Long Beach Pike amusement park forty years apart. As shown below, they nearly crossed paths beside the Keller Building in Santa Monica as well.

During Harold Lloyd’s 1924 feature comedy Hot Water, the family’s inaugural drive in Harold’s new car ends in disaster. Their trouble begins when the car grid-locks the intersection at 3rd and Broadway in Santa Monica. The Keller Building at back was built in 1893. The yellow box matches the trio of images further above.

Thanks to movie editing, moments after Harold pushes the family car out of this intersection in low-lying Santa Monica (above), the car careens down Bunker Hill on Olive Street in downtown Los Angeles, a setting also appearing in the 1952 noir classic The Turning Point, as described in this post HERE.

If the Cleavers live in Santa Monica, then Ward must work in West Hollywood! During the episodes “Beaver on TV” (Season 6: Episode 22; first broadcast February 21, 1963), and “Lumpy’s Scholarship (Season 6: Episode 24; first broadcast, March 7, 1963) this establishing shot of Ward’s office was filmed at 9034 Sunset Boulevard.

Although the flagstone detailing has been replaced with brick, and a shabby portico with columns has been added, the basic box-like design and proportions of Ward’s office remain unchanged. (C) 2013 Google.

If you enjoy looking at studio backlots, the wonderful Retroweb site shows how the Cleaver’s home and neighborhood were part of the Colonial Street backlot at Universal Studios. Beaver and Gilbert even walk past the Munster’s home in one episode!

If you enjoy looking at studio backlots, the wonderful Retroweb site shows how the Cleaver’s home and neighborhood were part of the Colonial Street backlot at Universal Studios. Beaver and Gilbert even walk past the Munster’s home in one episode!

Leave it to Beaver – (C) 1962, (C) 1963 Revue Studios. HAROLD LLOYD images and the names of Mr. Lloyd’s films are all trademarks and/or service marks of Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc. Images and movie frame images reproduced courtesy of The Harold Lloyd Trust and Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc.

Third Street Promenade, Santa Monica, CA

View Larger Map

Filed under: Harold Lloyd, Hot Water, Leave It To Beaver, TV Shows Tagged: El Miro, Harold Lloyd, Hot Water, Leave it to Beaver, Santa Monica, Silent Comedians, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, then and now