John Bengtson's Blog, page 23

June 12, 2014

Chaplin’s First Scene – a Very Busy Place to Film

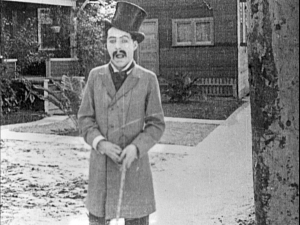

Chaplin’s on-screen debut. Movie theater audiences first set eyes on Chaplin, this image of Chaplin, on February 2, 1914, 100 years ago.

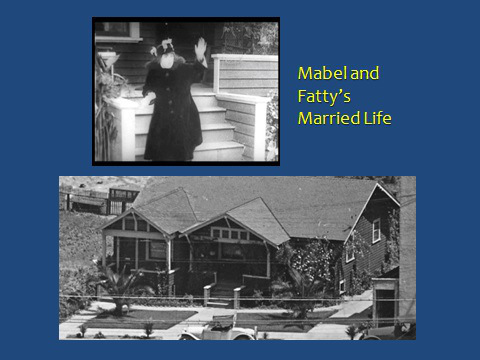

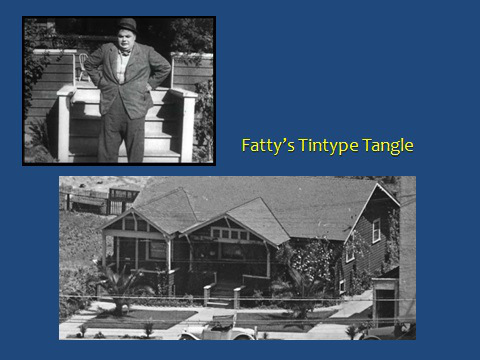

In one of my earliest posts (reprinted below), I reported that the site of Chaplin’s first scene, from his initial movie Making a Living (1914), was filmed in front of a residential porch adjacent to the Keystone Studio that is now the site of a drive-way for a Jack-In-The-Box restaurant. Upon further study, I realized that this porch appeared in FIVE other Chaplin Keystone films, and that the same porch appeared in many other Keystone films as well. Here, below, are these five other Chaplin films, followed by five more Keystone titles, all filmed on the porch of the home that once stood due north of the Keystone Studio, where Chaplin filmed his very first scene.

[Reprint of original post] Following the release of the Chaplin at Keystone DVD Collection, for which I prepared a bonus feature program, Kevin Dale contacted me wondering if Chaplin had filmed the opening scene from his inaugural film Making a Living in front of the home adjoining the Keystone Studio. The Keystone Studio environs frequently appear in Keystone productions, and after close study I am convinced Kevin is correct. Assuming they shot Making a Living in sequential order, this marks the very first scene of Chaplin’s entire career. It also means that when the film opened on February 2, 1914, 100 years ago, it was through this scene that movie audiences were first introduced to young Mr. Chaplin. The site is now a driveway to a Jack-in-the-Box restaurant, while the main filming stage remains in use today as a Public Storage warehouse.

The large Keystone Studio stage with the sign on the roof is still standing. Marc Wanamaker – Bison Archives

Comparing details likely confirms the location. Notice the matching white trim of the square front porch steps, and the matching pair of palm trees.

The site is located approximately at 1710 Glendale Boulevard in Echo Park. Bing Maps Bird’s Eye – © 2010 NAVTEQ, Pictometry Bird’s Eye © 2010 Pictometry International Corp., © 2010 Microsoft Corporation.

Chaplin at Keystone: Copyright (C) 2010 by Lobster Films for the Chaplin Keystone Project.

Young Mr. Chaplin stood here:

View Larger Map

Filed under: Chaplin Tour, Charlie Chaplin, Keystone Studio Tagged: Chaplin 100 years, Chaplin at 100, Chaplin Centennial, Chaplin Tour, Charlie Chaplin, Keystone Studio, Making a Living, Silent Comedians, Silent Comedies, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, then and now

May 18, 2014

Max Linder Shines Again in Seven Years Bad Luck

Click to enlarge – Max Linder in 1921 beside the extant home at 1366 E Palm in Altadena

Dapper Max Linder, the pioneering French silent film comedian affectionately dubbed “The Professor” by Charlie Chaplin, will be taking the spotlight soon. Max’s 1921 feature comedy Seven Years Bad Luck will be screened at the San Francisco Silent Film Festival, and will be released by Kino-Lorber on video along with three other Linder films as part of The Max Linder Collection. Preservationist and

Dapper Max Linder, the pioneering French silent film comedian affectionately dubbed “The Professor” by Charlie Chaplin, will be taking the spotlight soon. Max’s 1921 feature comedy Seven Years Bad Luck will be screened at the San Francisco Silent Film Festival, and will be released by Kino-Lorber on video along with three other Linder films as part of The Max Linder Collection. Preservationist and

The Blacksmith – new footage

entertainer Serge Bromberg, the founder of Lobster Films (the company responsible for restoring these films), will be presenting Seven Years Bad Luck at the festival on June 1 at 10:00 a.m. The previous day, on May 31 at noon, Bromberg will screen a host of film treasures, including the recently discovered “lost” version of Buster Keaton’s The Blacksmith, as featured here in my three-part series of posts.

Although born in France, Linder moved to the United States in 1918, and was soon filming across Los Angeles and Hollywood at the same spots favored by his American contemporaries. Below, Max races north up Cahuenga across Hollywood Boulevard.

Looking toward the SE corner of Cahuenga and Hollywood Boulevard. Max (red oval) races up Cahuenga while the yellow oval marks where Buster Keaton grabbed a passing car one-handed in Cops (1922).

The intersection of Cahuenga and Hollywood Boulevard, depicted in Max’s movie, upper left, above, has appeared in dozens of films and in several of my prior posts, including this one about Mary Pickford HERE.

Lost to the Santa Monica freeway, this home once stood at 15 Berkeley Square. Comedy producer Hal Roach lived on the same gated block at No. 22.

Seven Years Bad Luck includes scenes filmed at the Santa Fe Depot, an extremely popular place to film, including the Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy comedy short Berth Marks (1929) (below).

Ollie and Stan in Berth Marks (left) – Max at right. The same Western Union sign (oval) appears in each shot.

Below, a view of Max at the front of the former Santa Fe depot.

There are many more locations to report, but I’ll close with a connection between Max and the D.W. Griffith 1916 masterpiece Intolerance. Both movies include scenes filmed on Buena Vista Street beside the former L.A. County Jail.

Click to enlarge. Max hides behind a car in Seven Years Bad Luck (upper left) – the Dear One desperately races to halt the execution of an innocent man in Intolerance (upper right). The car in both movie images is pointed the same direction east up Buena Vista Street, standing near the oval in the photo, by the side of the L.A. County Jail fronting Temple Street.

Seven Years Bad Luck restoration (C) 2014 Lobster Films.

Filed under: Uncategorized Tagged: Buster Keaton, Hollywood, Intolerance, Los Angeles Historic Core, Max Linder, San Francisco Silent Film Festival, Seven Years Bad Luck, Silent Comedians, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, The Blacksmith, then and now

May 11, 2014

Keaton’s Heart in San Francisco – The Navigator

Buster Keaton in The Navigator looking north up Divisadero towards the corner of Broadway, in San Francisco.

The 2014 San Francisco Silent Film Festival concludes Sunday, June 1, with a screening of Buster Keaton’s 1924 classic The Navigator, a personal favorite of Buster, and one of his most successful films.

Early on The Navigator features a joke involving a U-turn. I won’t spoil the punchline, but it’s striking that the sequence was filmed hundreds of miles from Hollywood in the luxurious Pacific Heights neighborhood of San Francisco. As I explain with three examples in this post, Keaton the filmmaker went to great lengths to capture perfect scenes for this movie.

Click to enlarge – portraying Buster’s mansion, the residence of Mr. A.D. Moore stood at 2500 Divisadero, once the only home on the east side of the street. The entrance-way to Buster’s mansion appearing in the movie has no flight of steps down, and thus was filmed elsewhere.

Although two Keaton biographies mention Buster filming scenes from The Navigator in San Francisco, neither cites a source for this detail, and neither provides a rationale for deciding to shoot so remotely.

(Click to enlarge) Then and Now – the red brick home at the far left has lost its front portico, while the neighboring white portico home has been torn down and replaced with two smaller homes. At back, the homes on the SW and NW corners of Broadway remain standing. The chimneys on the back NW corner home have been relocated from exterior to interior walls. At right, four homes now replace the Moore residence.

Keaton was both pragmatic and uncompromising as a filmmaker. He filmed dozens of prosaic insert shots for his movies, such as scenes of people walking along sidewalks, or crossing streets, directly across the street from his small studio. But as shown above, he would travel hundreds of miles to find the perfect setting for a gag.

Keaton was both pragmatic and uncompromising as a filmmaker. He filmed dozens of prosaic insert shots for his movies, such as scenes of people walking along sidewalks, or crossing streets, directly across the street from his small studio. But as shown above, he would travel hundreds of miles to find the perfect setting for a gag.

As I ponder in my book Silent Echoes, Keaton could have staged this U-turn scene from The Navigator at any number of posh Los Angeles neighborhoods. But as you watch the scene, instead of seeing rows of mansions on either side of the street receding into the distance, you’ll notice you don’t see anything at all.

By filming from a low angle on the crest of a hill, Buster eliminated the background, focusing our attention on the foreground action. We may never know whether Keaton used this gag as a ploy to take a fun trip to San Francisco he could write off as an expense, or whether instead he thought the setting was so perfectly configured for portraying the joke that it justified an excursion north, but either way Buster carefully exploited San Francisco’s unique topography to full effect.

By filming from a low angle on the crest of a hill, Buster eliminated the background, focusing our attention on the foreground action. We may never know whether Keaton used this gag as a ploy to take a fun trip to San Francisco he could write off as an expense, or whether instead he thought the setting was so perfectly configured for portraying the joke that it justified an excursion north, but either way Buster carefully exploited San Francisco’s unique topography to full effect.

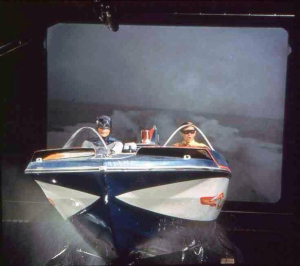

A second example of Keaton’s determination when filming The Navigator occurs early on as well. As a visual storyteller, Keaton wanted to show in a single shot both the conspirators planning to destroy an ocean liner and the ship itself. To do so, in an era preceding the rear-screen projection special effect (see convincing example at left!), Keaton built a special set on a bluff overlooking the Redondo Beach pier (see below). Notice that the temporary set had no roof, but was instead covered with muslin to diffuse the natural sunlight for filming.

A second example of Keaton’s determination when filming The Navigator occurs early on as well. As a visual storyteller, Keaton wanted to show in a single shot both the conspirators planning to destroy an ocean liner and the ship itself. To do so, in an era preceding the rear-screen projection special effect (see convincing example at left!), Keaton built a special set on a bluff overlooking the Redondo Beach pier (see below). Notice that the temporary set had no roof, but was instead covered with muslin to diffuse the natural sunlight for filming.

The conspirators hatch their evil plan from within a tiny set overlooking Redondo Beach.

The Black Pirate

The Navigator’s stunning underwater sequence provides a third example of Keaton’s uncompromising dedication to his craft. It was common practice at the time for movies to depict underwater scenes by placing a narrow aquarium, filled with bubbles and live fish, between the camera and the actors, hoisted on wires to appear buoyant while working on a dry set. Filming the dry actors through the “window” of the aquarium created a serviceable underwater image. Douglas Fairbanks used this technique to great effect for a brief “swimming” shot of marauding thieves in The Black Pirate (1926).

And yet for The Navigator Keaton donned a deep-sea diving suit, and spent a month filming in the clear but frigid waters of Lake Tahoe. He didn’t have to do this. Buster could have used The Black Pirate effect (above), or easily hired a stunt man to take his place in the identity-concealing suit. Instead Buster built a diving helmet with a special glass panel large enough to reveal his entire face, so the audience would always know it was really him beneath the waves. Buster knew the audience could tell the difference between a true and staged effect, and thus did his utmost to film things without fakery throughout his career. The resulting scene completely captures your attention, and ranks among the best (and perhaps only) true underwater sequence from the entire silent film era.

And yet for The Navigator Keaton donned a deep-sea diving suit, and spent a month filming in the clear but frigid waters of Lake Tahoe. He didn’t have to do this. Buster could have used The Black Pirate effect (above), or easily hired a stunt man to take his place in the identity-concealing suit. Instead Buster built a diving helmet with a special glass panel large enough to reveal his entire face, so the audience would always know it was really him beneath the waves. Buster knew the audience could tell the difference between a true and staged effect, and thus did his utmost to film things without fakery throughout his career. The resulting scene completely captures your attention, and ranks among the best (and perhaps only) true underwater sequence from the entire silent film era.

Was there ever a more heroic filmmaker than Buster Keaton? Buster clambered around trains, paddle-wheelers, and sailing ships; navigated white-water rapids and the open ocean; outran hordes of police and herds of cattle; rode horses; worked with lions and bears; braved cyclones, dodged collapsing buildings, and plunged off of waterfalls. And for a month he donned a 200 pound claustrophobic suit to film at the bottom of Lake Tahoe. Buster put his heart and soul into every movie he made, and as a result, ninety years later they still continue to amaze and entertain.

Was there ever a more heroic filmmaker than Buster Keaton? Buster clambered around trains, paddle-wheelers, and sailing ships; navigated white-water rapids and the open ocean; outran hordes of police and herds of cattle; rode horses; worked with lions and bears; braved cyclones, dodged collapsing buildings, and plunged off of waterfalls. And for a month he donned a 200 pound claustrophobic suit to film at the bottom of Lake Tahoe. Buster put his heart and soul into every movie he made, and as a result, ninety years later they still continue to amaze and entertain.

Day Dreams

PS – as I explain in my book, Keaton previously staged a chase scene from his short film Day Dreams (1922) in San Francisco, while ingeniously cutting back and forth with scenes filmed in Hollywood. You can read about these North Beach/Financial District locations at this link below.

Buster Keaton San Francisco Location Tour

Here’s The Navigator U-turn setting as it appears today.

View Larger Map

Filed under: Buster Keaton Tagged: Broadway, Divisadero, Hollywood, Keaton Locations, Pacific Heights, San Francisco, San Francisco Silent Film Festival, San Francisco then and now, Silent Comedians, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, The Navigator, then and now

May 4, 2014

Chaplin – Caught In the Rain 100 Years Ago by the 2nd St Tunnel

Caught in the Rain (1914) – looking east down 2nd Street from near Bolyston Street towards Bunker Hill.

Charlie Chaplin’s lucky 13th Keystone Studio movie Caught in the Rain was released May 4, 1914, one hundred years ago today. Although Chaplin credits this film in his autobiography as his first directorial effort, Chaplin biographer David Robinson suggests otherwise, due to the handwritten filmography Charlie sent to his brother Syd in August 1914, citing a prior film, Twenty Minutes of Love, as one of Charlie’s “own.”

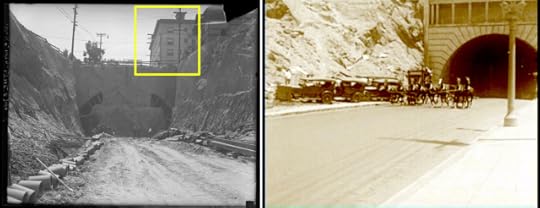

Looking east towards the Hotel Stanley at the SE corner of 2nd and Flower. The left box marks the uphill slope of 2nd Street that was excavated reaching towards where the west portal of the tunnel (right box) was built at Flower St.

In either case, the clarity of Caught in the Rain (part of the Chaplin at Keystone collection from Flicker Alley, restored by Cineteca di Bologna and the British Film Institute in association with Lobster Films), provides a rare view of early Los Angeles, looking east down 2nd Street towards Bunker Hill, with the downtown Los Angeles core, out of sight, on the other side of the hill.

East view towards the west portal of the tunnel under construction, with the Hotel Stanley (box) looking down. A comparable view of the finished west portal appeared in the Mack Sennett comedy Circus Today (1926).

November 7, 1920 – Los Angeles Times

2nd Street had long been a major transportation bottleneck, as traffic from Hollywood and Glendale had to be diverted south from 2nd Street, around Bunker Hill, before entering the city. Construction of the 2nd Street Tunnel began in 1921, nearly seven years after Chaplin had filmed.

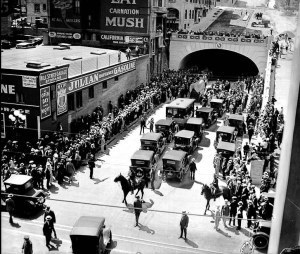

The 2nd Street Tunnel was hailed as the greatest undertaking of its kind that Los Angeles had put through, both longer and wider than the city’s first tunnel, built at 3rd Street in 1900. Completion of the tunnel, which commenced April 11, 1921, was optimistically projected to take 15 months. By the time it officially opened on July 25, 1924, more than 39 months had passed. The photo at right shows the east portal during the tunnel’s opening celebration.

The 2nd Street Tunnel was hailed as the greatest undertaking of its kind that Los Angeles had put through, both longer and wider than the city’s first tunnel, built at 3rd Street in 1900. Completion of the tunnel, which commenced April 11, 1921, was optimistically projected to take 15 months. By the time it officially opened on July 25, 1924, more than 39 months had passed. The photo at right shows the east portal during the tunnel’s opening celebration.

The trolley tracks appearing in the movie frame at top turned right (south) at Figueroa, to avoid going over the hill. The Hotel Stanley at the SE corner of 2nd and Flower Street (highlighted above and at left) overlooked the west portal of the completed tunnel.

The trolley tracks appearing in the movie frame at top turned right (south) at Figueroa, to avoid going over the hill. The Hotel Stanley at the SE corner of 2nd and Flower Street (highlighted above and at left) overlooked the west portal of the completed tunnel.

Chaplin at Keystone: Copyright (C) 2010 by Lobster Films for the Chaplin Keystone Project.

A comparable view today on Google Street View.

View Larger Map

Filed under: Bunker Hill, Charlie Chaplin, Keystone Studio, Los Angeles Historic Core Tagged: bunker hill, Caught In The Rain, Chaplin Locations, Chaplin Tour, Charlie Chaplin, Keystone Studio, Los Angeles Historic Core, Silent Comedians, Silent Comedies, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, then and now

April 22, 2014

Chaplin – 100 Years Ago on Sunset Boulevard

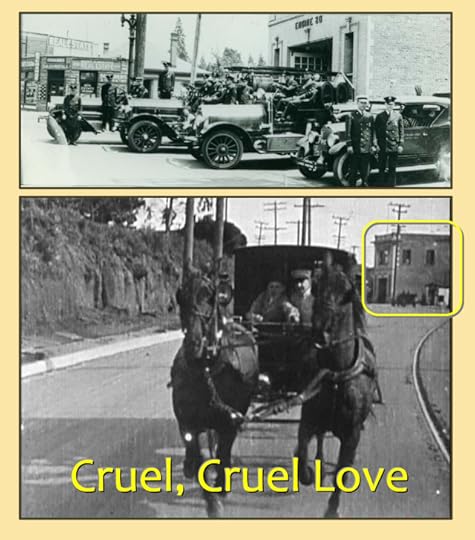

Tillie’s Punctured Romance (1914) looking west towards Engine Co. No. 20 at 2144 Sunset Blvd. A modern structure for Engine Co. No. 20 stands at the same address today. LAFD Photo Album Collection

“Sunset Boulevard” – few words evoke the mystique and glamour of Southern California more than the name of this historic street that wends its way west from the heart of downtown Los Angeles to the Pacific Ocean. As discussed here, the busy street passed within a few blocks of the Keystone Film Co. studios where Charlie Chaplin began his film career in 1914. The remarkable image quality of the new Chaplin at Keystone collection from Flicker Alley confirms Chaplin filmed many scenes on Sunset Blvd. more than three decades before the landmark film starring Gloria Swanson and William Holden premiered in 1950.

Standing Pat (1928) looking west down Sunset towards Engine Co. No. 20. The tall back tower (box) told me this building was likely a fire station.

At top of this post, a band of Keystone Kops fall over themselves during the chase and gunfight climax of Tillie’s Punctured Romance, starring Charlie Chaplin, Marie Dressler, and Mabel Normand. I solved the Tillie location when I noticed it was the same street scene (directly above) appearing in Standing Pat, “A Ton of Fun” comedy starring the overweight trio Hilliard Karr, Frank Alexander, and ‘Kewpie’ Ross. The tall narrow tower (box, above) was a common feature used at fire stations to hang wet hoses to dry, and checking the Los Angeles Fire Department Historical Society confirmed the setting as 2144 Sunset Blvd.

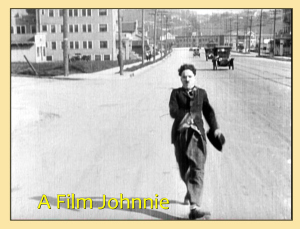

Engine Co. No. 20 appearing both in Tillie’s Punctured Romance and in A Film Johnnie (1914) as the trolley tracks on Sunset curve north at Mohawk Bend.

The “transitive theory of film location confirmation” now starts kicking into high gear. Standing Pat confirmed the fire station at the SW corner of Sunset and Mohawk Street, which confirmed Tillie, so when I noticed the station also overlaps with a scene from Chaplin’s A Film Johnnie (above), the station confirmed that movie as well. A leads to B leads to C.

Eastward views towards Engine Co. No. 20 (LAFD Photo Album Collection – courtesy Mrs. George Walker) and in Cruel, Cruel Love (1914). The ambulance is heading west from Mohawk Bend on Sunset.

Switching perspective, now looking east towards Mohawk Bend on Sunset, the fire station at top confirms the above scene from Chaplin’s Cruel, Cruel Love was also filmed on Sunset.

Knowing Chaplin filmed one scene for A Film Johnnie looking west beside the trolley lines on Sunset, it seemed likely the scene to the left was also filmed beside the Sunset trolley line, only this time looking east.

Knowing Chaplin filmed one scene for A Film Johnnie looking west beside the trolley lines on Sunset, it seemed likely the scene to the left was also filmed beside the Sunset trolley line, only this time looking east.

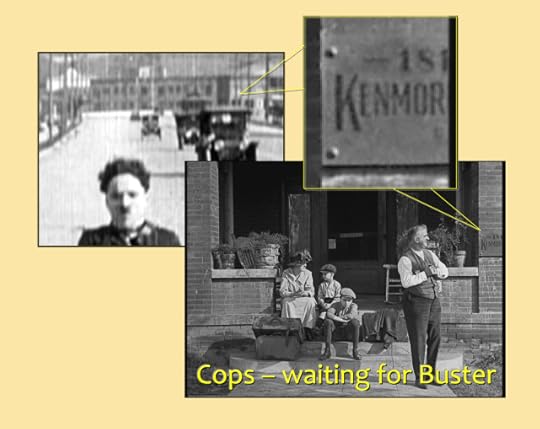

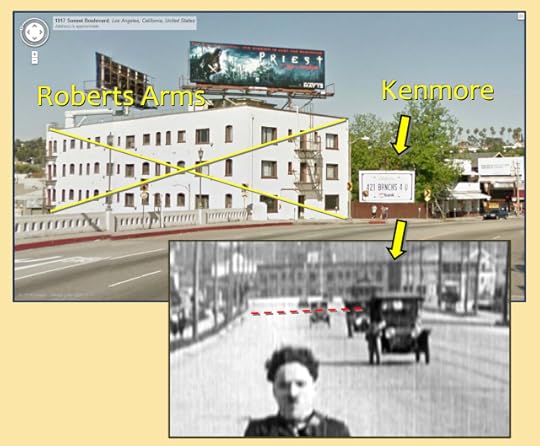

The extant Kenmore Apartment building at back – the dotted red line marks the guard rail where Sunset crosses over Glendale Blvd.

The Kenmore Apartments building (1827 Sunset – originally numbered 1817 Sunset – built in 1912) stands behind Charlie, above, confirming the view east down Sunset towards the Glendale Blvd. overpass railing (dotted red line).

The Kenmore Apartments as it appears during a scene from Cops (1922). Originally numbered 1817 Sunset, a portion of the apartment sign reading “181* Kenmor*” appears at back. The front of the Kenmore was remodeled with streamline moderne elements, perhaps in the 1930s, to accommodate commercial store fronts on the ground floor.

Remarkably, the Kenmore Apartments played a later role in film history, portraying the new home of the family whose wagon-load of furniture is destroyed during Buster Keaton’s classic short film Cops.

A modern close view of the Sunset/Glendale overpass (dotted red line)

Although the Kenmore (built in 1912) is still standing, it’s no longer possible to replicate the view of the Sunset/Glendale overpass from A Film Johnnie as the more “modern” Roberts Arms (built in 1922) today blocks the view.

Recapping – Engine Co. No. 20 at Mohawk Bend as it appears in A Film Johnnie, Tillie’s Punctured Romance, and Standing Pat. A comparable view of the larger, modern fire station on the same corner appears below.

View Larger Map

For another fun location from A Film Johnnie, you can read HERE how the beautiful (and still standing) Bryson Apartment building stood in for the Keystone Studios during the film.

For additional Sunset history connections: (1) as explained in my book Silent Traces, Chaplin filmed his roller skate escape at the conclusion of The Rink (1916) along Sunset Blvd. near Occidental Blvd., and filmed a discarded scene from The Circus (1928) along the Sunset Strip near the former Café La Boheme at 8614 Sunset Blvd., (2) Buster Keaton filmed a scene from Cops at Sunset Blvd. and Detroit, a block from the Chaplin Studio, as shown in my post HERE; and (3) family-man Ward Cleaver’s office in the Leave it to Beaver TV show was located at 9034 Sunset Boulevard, as shown in my post HERE.

Chaplin at Keystone: Copyright (C) 2010 by Lobster Films for the Chaplin Keystone Project. Cops licensed by Douris UK, Ltd. Special thanks to Robert Arkus for supplying me with a copy of Standing Pat.

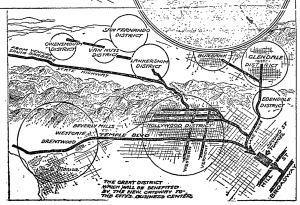

This maps shows the Keystone Studio site at 1712 Allesandro relative to Engine Co. No. 20 at Mohawk Bend, and the Kenmore Apartments near the Glendale Blvd. overpass.

View Larger Map

Filed under: Charlie Chaplin, Cops Tagged: A Film Johnnie, Chaplin Locations, Charlie Chaplin, Cops, Cruel Cruel Love, Hollywood, Keystone Comedies, Keystone Studio, Silent Comedians, Silent Comedies, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, Standing Pat, Sunset, Sunset Boulevard, then and now, Tillie's Punctured Romance

April 9, 2014

Harold Lloyd’s Why Worry? TCM Hollywood Connection

In honor of the 2014 TCM Classic Film Festival screening of Harold Lloyd’s 1923 feature comedy Why Worry? at the Egyptian Theater on Friday, April 11 at 7:15 pm, here are a couple of quick views from the conclusion of the film. Lloyd’s granddaughter Suzanne will be in attendance, while composer Carl Davis will be on hand to conduct his original orchestral score for the film.

Looking west down Hollywood Blvd. as actor John Aasen directs traffic at the intersection of Cahuenga. The extant Toberman Hall (1907 – yellow oval) and Hotel Christie (red box, and below) appear at back.

Why Worry? concludes with Harold sprinting down Hollywood Boulevard to share with his friend, a gentle giant played by John Aasen, the news that Harold’s character has just become a father (see top). They celebrate in the intersection of Cahuenga Boulevard, the same spot where Charlie Chaplin and Marie Dressler filmed Tillie’s Punctured Romance (1914), and near where Mary Pickford shot a 1918 Liberty Bond promotional film (see below). You can read more about Chaplin and Pickford filming at this Hollywood landmark at these posts HERE and HERE.

Why Worry? concludes with Harold sprinting down Hollywood Boulevard to share with his friend, a gentle giant played by John Aasen, the news that Harold’s character has just become a father (see top). They celebrate in the intersection of Cahuenga Boulevard, the same spot where Charlie Chaplin and Marie Dressler filmed Tillie’s Punctured Romance (1914), and near where Mary Pickford shot a 1918 Liberty Bond promotional film (see below). You can read more about Chaplin and Pickford filming at this Hollywood landmark at these posts HERE and HERE.

Click to enlarge – the same corner appearing in Tillie’s Punctured Romance and in Mary Pickford 100% American.

With a bit of movie editing magic, while the giant stands at Cahuenga looking east as Harold runs towards him, the matching shot of Harold running west towards the giant was staged at Hollywood Boulevard beyond Sycamore Avenue, many blocks west from where the giant was standing (see below). You can read more about this setting, and how it appears in Buster Keaton’s Sherlock Jr. (1924) at this post HERE.

Looking east down Hollywood Blvd. past the former Richfield gas station on the corner of Sycamore, as appearing in Lloyd’s Girl Shy (1924) left, and in Why Worry? (right). Harold is supposedly running towards the giant who was actually filmed several blocks behind where Harold is running.

HAROLD LLOYD images and the names of Mr. Lloyd’s films are all trademarks and/or service marks of Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc. Images and movie frame images reproduced courtesy of The Harold Lloyd Trust and Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc.

Google Street View today.

View Larger Map

Filed under: Harold Lloyd, Hollywood Tour Tagged: Harold Lloyd, Hollywood, Hollywood Tour, Lloyd Studio, Silent Comedians, Silent Comedies, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, TCM, TCM Festival, then and now, Tillie's Punctured Romance, Why Worry?

March 30, 2014

Chaplin Leads the Gang to the Hollywood Police

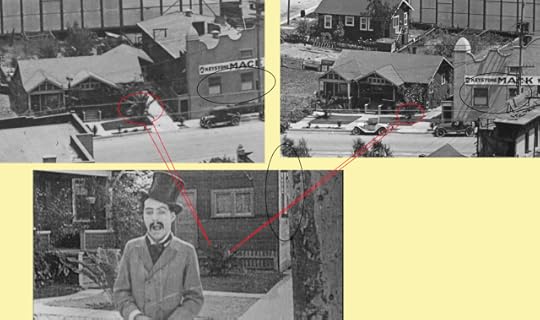

As I explain in my book Silent Traces, Charlie Chaplin’s landmark short film Easy Street (1917) contains scenes filmed on extant Olvera Street in downtown Los Angeles (see below), where he would return a few years later to film his re-union with Jackie Coogan in The Kid (1921) (see The Kid post HERE). The Easy Street “T” intersection exterior set (left), was built in Hollywood within the NE corner of

As I explain in my book Silent Traces, Charlie Chaplin’s landmark short film Easy Street (1917) contains scenes filmed on extant Olvera Street in downtown Los Angeles (see below), where he would return a few years later to film his re-union with Jackie Coogan in The Kid (1921) (see The Kid post HERE). The Easy Street “T” intersection exterior set (left), was built in Hollywood within the NE corner of  Cahuenga and Romaine at the tiny Lone Star Studio backlot, the same spot where Buster Keaton, after taking over the studio in 1920 for his own productions, would build a similar “T”-shaped tenement set for his short film Neighbors (1920) (right).

Cahuenga and Romaine at the tiny Lone Star Studio backlot, the same spot where Buster Keaton, after taking over the studio in 1920 for his own productions, would build a similar “T”-shaped tenement set for his short film Neighbors (1920) (right).

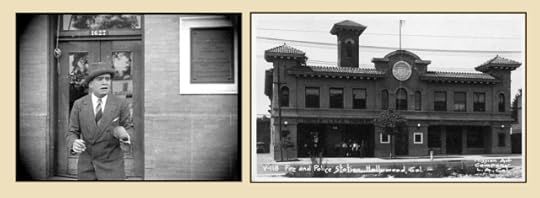

Should I stay or should I go? Charlie at the doorway. Postcard Tommy Dangcil

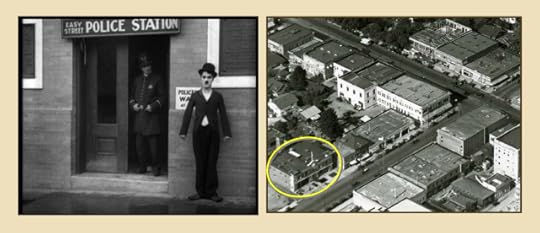

Despite reportedly spending $10,000 building his Easy Street set, Chaplin used a real police station (above) to film the scene where Charlie deliberates whether to join the force. His movements are a tour de force, showing the audience, through his physicality, his inner turmoil as he summons the courage to enter the building in order to enlist, then balks at the threshold, halting mid-step, then regains his nerve, marches towards the door, only to hesitate yet again. The scene was likely filmed in December 1916.

Doug’s turn at the station.

A few months later, Charlie’s friend Douglas Fairbanks would film his short comedy Flirting With Fate (1917) at the same police-station doorway (above).

Harry Langdon, left, in Plain Clothes (1925) - Stan Laurel, right, in Mixed Nuts (1922).

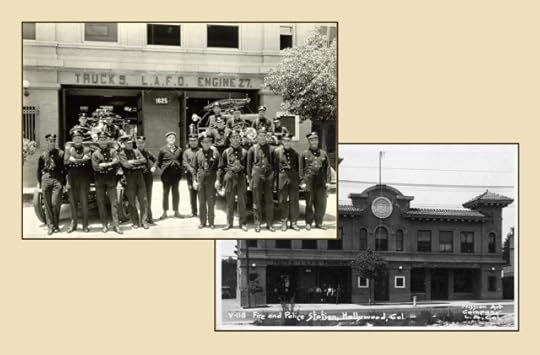

Following Charlie and Doug, the joint fire/police station, once standing at 1625-1627-1629 Cahuenga Boulevard, would become a very popular place to film. This makes perfect sense, as fire houses and police stations are commonly employed in all types of movies, and this was THE station serving most of Hollywood. I write much more about the joint station’s appearances in a prior post HERE. As shown above and below, Harry Langdon, Stan Laurel, Lloyd Hamilton, Harold Lloyd, and Buster Keaton all filmed in front of the station, and if I had to guess, nearly every other silent comedian likely filmed here as well.

Comedian Lloyd Hamilton’s turn – film unknown.

Harold Lloyd in Hot Water – Buster Keaton in Three Ages

The station appeared in Buster Keaton’s feature films Three Ages (1923) (above, right) and The Cameraman (1928), as well as in Harold Lloyd’s Safety Last! (1923) and Hot Water (1924) (above, left), and the early 1924 Our Gang short comedy High Society. The station no doubt appears in dozens of other films, including the newspaper drama The Last Edition (1925) (see below) reported HERE. What’s more, Keaton used the alley along the south side of the station for scenes from three different short films; The Goat (1921), Hard Luck (1921), and Neighbors (1920) (see post HERE).

The joint fire-police station appearing in The Last Edition. Photo Tommy Dangcil.

Click to enlarge. Eric Campbell chases Charlie onto the Plaza de Los Angeles in Easy Street. USC Digital Library

Chaplin fashioned his tenement set for Easy Street after Methley Street, in his boyhood London neighborhood Lambeth. To add greater realism, he also filmed at the Plaza de Los Angeles (above), and nearby Olvera Street, a slum alley that is today a popular Mexican market and tourist attraction.

Click to enlarge. Chaplin used the same slum alley for both films.

Above, four views of Olvera Street, a dingy slum alleyway at the time Chaplin filmed The Kid and Easy Street, reminiscent of his boyhood home (see more on The Kid at this post HERE). Today Olvera Street is one of LA’s most popular tourist spots.

All images from Chaplin films made from 1918 onwards, copyright © Roy Export Company Establishment. CHARLES CHAPLIN, CHAPLIN, and the LITTLE TRAMP, photographs from and the names of Mr. Chaplin’s films are trademarks and/or service marks of Bubbles Incorporated SA and/or Roy Export Company Establishment. Used with permission. Easy Street special edition (C) 2006 Film Preservation Associates.

Flirting With Fate (1917)—Douglas Fairbanks: A Modern Musketeer Collection (David Shepard, Film Preservation Associates, Jeffrey Masino, Flicker Alley LLC).

Neighbors (1920); Three Ages (1923) licensed by Douris UK, Ltd.

HAROLD LLOYD images and the names of Mr. Lloyd’s films are all trademarks and/or service marks of Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc. Images and movie frame images reproduced courtesy of The Harold Lloyd Trust and Harold Lloyd Entertainment Inc.

Plain Clothes (C) 2007 All Day Entertainment and Lobster Films.

Site of the former Hollywood joint fire/police station

View Larger Map

Filed under: Buster Keaton, Chaplin Tour, Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, Harold Lloyd, Harry Langdon, Stan Laurel Tagged: Chaplin Locations, Chaplin Tour, Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, Easy Street, Harold Lloyd, Harry Langdon, High Society, Hollywood, Hollywood Tour, Keaton Locations, Lloyd Hamilton, Silent Comedians, Silent Comedies, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, Stan Laurel, The Kid, The Last Edition, then and now

March 17, 2014

Perry Mason at the Chaplin Studio – The Case of the Homecoming Kid

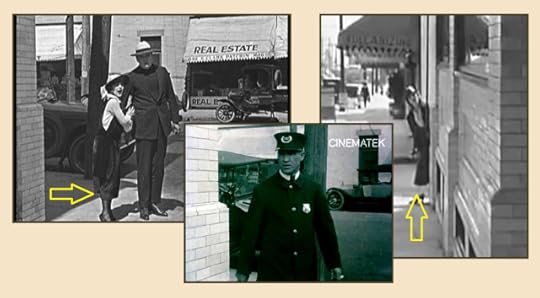

1966 – Perry Mason and Paul Drake arrive at the Chaplin Studio in The Case of the Final Fade-Out

2005 – a matching view of the entrance. Kermit the Frog, dressed as Chaplin, welcomes guests

One of the most gratifying experiences to come from working on my Charlie Chaplin book Silent Traces was being given a private tour of the Chaplin Studios, at 1416 N. La Brea Avenue in Hollywood, now home to The Jim Henson Company. My book contains an entire chapter devoted to the studio, annotated with vintage and current photos, aerial views, and maps.

Jackie Coogan in 1921 and 1966

The studio has a long history, and while I was aware that it was once used to film the Perry Mason television show, I was pleasantly surprised when Thomas Peters wrote to me advising that the studio exteriors appear prominently in the final episode of the series, The Case of the Final Fade-Out, which first aired May 22, 1966.

Richard Anderson, as Lt. Steve Frumm

Moreover, one of the guest stars in the final show was Jackie Coogan, the former child superstar who had worked at the same studio 45 years earlier when filming Chaplin’s masterpiece The Kid (1921). What bittersweet memories Jackie must have had revisiting the studio after all those years. His return must surely have been an on-set topic of conversation while filming the episode, and begs the question whether his casting was merely a coincidence, or an homage of some sorts.*

Three views of the studio film vault door – Chaplin’s butler (inset) retrieves Charlie’s most valuable possession from the vault, his tramp shoes.

Dick Clark at the gate

Given that this was the concluding episode of the highly successful series, after nine years, and 271 episodes, it must have been a bittersweet moment for everyone involved. Again, the choice of the title, Final Fade-Out, suggests a tribute to the show’s own passing.

Aside from Coogan’s appearance, a young-looking Dick Clark (is that redundant?) plays a major role, as does veteran character actress Estelle Winwood.

Erle Stanley Gardner

Erle Stanley Gardner, the prolific author of the original Perry Mason mystery novels, plays an un-credited cameo role as the last courtroom judge to appear in the series.

The plot involves a murder that takes place at a movie studio during the filming of a scene. Afterwards, the police briefly question a number of crew member witnesses, whose demeanor and appearance suggest they are all played by the real grips, camera operators, and other studio crew members from the show.

The final shot of the series

The closing shot of the series, Perry Mason (Raymond Burr), Paul Drake (William Hopper), and Della Street (Barbara Hale) confer about their next big case.

The Chaplin Studio during the Perry Mason years and originally. When La Brea Avenue was widened in 1929, and the sidewalk was moved several feet east, the protruding architectural details of the buildings north of the entrance gate (yellow line) were trimmed flush to the new sidewalk. The buildings south of the gate were physically moved east to preserve the details. Vintage Los Angeles

*(Oops, well, Coogan’s sentimental homecoming makes a good story, but it turns out he had appeared on the show twice before; in Season 5 – Episode 5, the Case of the Crying Comedian, and in Season 6 – Episode 28, the Case of the Witless Witness. Maybe those were nostalgic experiences for him as well.)

All images from Chaplin films made from 1918 onwards, copyright © Roy Export Company Establishment. CHARLES CHAPLIN, CHAPLIN, and the LITTLE TRAMP, photographs from and the names of Mr. Chaplin’s films are trademarks and/or service marks of Bubbles Incorporated SA and/or Roy Export Company Establishment. Used with permission.

Perry Mason © MCMLXVI Paisano Productions All Rights Reserved.

Filed under: Chaplin Studio, Chaplin Tour, Charlie Chaplin, The Kid Tagged: Chaplin Locations, Chaplin Studio, Chaplin Tour, Charlie Chaplin, Hollywood, Hollywood Tour, Jackie Coogan, Perry Mason, Silent Comedians, Silent Comedies, Silent Movie Locations, Silent Movies, The Case of the Final Fade-Out, The Kid, then and now

February 20, 2014

Mary Pickford and the Silent Stars Meet at One Hollywood Corner

Click to enlarge. Mary Pickford peers from an alley towards the corner where Mabel Normand waits to confront Charlie Chaplin and Marie Dressler in Tillie’s Punctured Romance (1914).

Mary Pickford in 100% American

America’s Sweetheart, Canadian-born Mary Pickford, was a staunch supporter of the World War I Liberty Bond campaign. Aside from selling millions of dollars of bonds at various rallies across the country, she also encouraged bond sales by starring in a patriotic movie entitled Mary Pickford 100% American (1918). You can see the movie (HERE).

The movie first caught my eye because early scenes depict the Abbot Kinney amusement park pier in Venice, California. As shown in my books, the pier had appeared previously in Charlie

Above, Harold Lloyd evades the police in Number Please?, while below Mary listens to a man selling Liberty Bonds in 100% American. Both views look west down the Abbot Kinney Pier, past the Ship Cafe at the left. Chaplin filmed The Adventurer at the far west end of the pier.

Chaplin’s The Adventurer (1917), and would later appear in Harold Lloyd’s Number Please? (1920) and in Buster Keaton’s The High Sign (filmed in 1920 – released in 1921). Although the pier burned down late in 1920, it was quickly re-built, and would appear again in such films as Laurel and Hardy’s Sugar Daddies (1927) and in Chaplin’s The Circus (1928).

Banking Hours Weekdays 10 – 3, Saturdays 9:45 – 12, Saturday Evenings 5 – 7

Throughout the movie Mary forgoes simple expenditures in order to save enough to purchase a bond. While waiting in line at the bank to make her purchase, Mary momentarily loses her bankroll, and accuses another patron of stealing it from her. While a bank guard harasses the falsely accused man, Mary recovers the money, makes her purchase, and dashes from the bank, calling out to the guard that it was all a mistake before she embarrassingly flees the bank and runs down the street.

After falsely accusing a man, Mary sheepishly peeks from an alley corner on the west side of Cahuenga.

When I noticed the distinctive BARKER’S BAKERY sign on Cahuenga above Mary’s head, I realized that the bank where Mary purchases her bond once stood at the corner of Hollywood Boulevard and Cahuenga – the intersection where so many other early movies were filmed. I report in prior posts (HERE) and (HERE) how Chaplin, Keaton, and Lloyd all filmed near this corner, but now we can add Mary Pickford to the mix.

Harold Lloyd’s future wife Mildred Davis in Never Weaken (1921), a policeman in the Christie comedy Hubby’s Night Out (1917), and Mary are all standing at the same alley corner on the west side of Cahuenga. As shown further below, the alley Buster Keaton used in Cops (1922) stands on the east side of Cahuenga.

As shown below, Douglas Fairbanks filmed a building-climbing stunt from Flirting With Fate (1916) just a bit down the street from Mary.

Click to enlarge. This view shows the west side of Cahuenga – the corner of Hollywood Blvd. at the right. Doug Fairbanks climbs up the front of the Fremont Hotel that stood south of the bakery.

Putting the elements together below, this single site represents a spot where many of Hollywood’s biggest stars; namely Charlie Chaplin, Mabel Normand, Marie Dressler, Harold Lloyd, Buster Keaton, Doug Fairbanks, and Mary Pickford, each filmed a scene.

Click to enlarge. Clockwise from the bottom, Harold Lloyd in Why Worry? (1923); Mabel Normand, Charlie Chaplin, and Marie Dressler in Tillie’s Punctured Romance; Buster Keaton in Cops; Doug Fairbanks in Flirting With Fate; and Mary Pickford in 100% American.

Below, Mary’s alley on the west side of Cahuenga.

Filed under: Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, Doug Fairbanks, Harold Lloyd, Venice Tagged: 100% American, Buster Keaton, Chaplin Locations, Charlie Chaplin, Cops, Doug Fairbanks, Flirting With Fate, Harold Lloyd, Hollywood, Keaton Locations, Mary Pickford, Never Weaken, Number Please?, Silent Comedians, Silent Comedies, Silent Movies, then and now, Tillie's Punctured Romance, Why Worry?

January 26, 2014

Laurel & Hardy Hit The Skids

During their ride home from the hospital in County Hospital (1932), Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy (well, their stunt doubles) skid at a wide intersection beside a Gothic-windowed auto garage. The zig-zag detailing remains on the garage wall.

This unusual intersection also appeared in the Hal Roach “Taxi Boys” comedies Thundering Taxis (1932) and What Price Taxi? (1932). The curb in the latter film says “TILDEN AVE,” identifying the spot as where Washington Place, Tilden Avenue, and Washington Boulevard meet. The two skid stunts depicted here were likely staged at this spot (red oval below) because the intersection was unusually wide, providing an extra measure of safety.

The Culver City Rollerdrome skating rink (yellow box, left) stood near the wide intersection, and for a time a mini-golf course (green box) stood on the corner. The Rollerdrome (1929-1970) was a local landmark for decades. The mini-golf course sign appears in the movie frame below.

The Culver City Rollerdrome skating rink (yellow box, left) stood near the wide intersection, and for a time a mini-golf course (green box) stood on the corner. The Rollerdrome (1929-1970) was a local landmark for decades. The mini-golf course sign appears in the movie frame below.

The Culver City Rollerdrome stood by the short-lived mini-golf course (notice the Golf sign)

Below, these vintage aerial photo details show the large skating rink beside a flat patch of earth where the mini-golf course stood. The garage with the Gothic windows stands near the corner – the skid area marked with a red oval.

Marc Wanamaker – Bison Archives

Tellefson Park stands today on the site of the former Rollerdrome and mini-golf course, and the corner garage still services cars.

(C) Hal Roach Studios, Inc.

View Larger Map

Filed under: Laurel and Hardy Tagged: Culver City, Hal Roach, Laurel and Hardy film locations, Silent Comedians, Silent Comedies, Silent Movie Locations, then and now