Brian Clegg's Blog, page 107

November 20, 2013

White sharks and romantic comedy

I'd like to introduce another of my guest bloggers: Ute (who pronounces her name Oooh-tah) Carbone is a multipublished author of women’s fiction, comedy, and romance. She lives with her husband in New Hampshire, where she spends her days walking, eating chocolate and dreaming up stories. Find out more about Ute and her work at her website.

I'd like to introduce another of my guest bloggers: Ute (who pronounces her name Oooh-tah) Carbone is a multipublished author of women’s fiction, comedy, and romance. She lives with her husband in New Hampshire, where she spends her days walking, eating chocolate and dreaming up stories. Find out more about Ute and her work at her website.GUEST POST

Last summer, the great whites came to Cape Cod. There were multiple sightings of these sharks in the waters off the Cape Cod National Seashore. In July, a great white shark attacked a man kayaking near Nauset Beach in Orleans. A few weeks later, a swimmer was bitten near Balston Beach in Truro. These were the first recorded incidents of shark attack on the Cape in seventy five years. Towns began to post warnings about getting into the water. On busy Labor Day Weekend, the bank holiday that marks the unofficial end of the summer season, beaches in Chatham and Orleans, a stretch that the Cape Cod Times dubbed “shark alley”, were closed to swimming. It was beginning to look like the opening to a sequel of Jaws.

I watched this unfolding story with great interest. I live in New England and have spent many a long weekend and holiday week enjoying the beaches on Cape Cod. I’m also a fiction writer and Provincetown, the fist at the end of Cape Cod’s arm, is the setting for my romantic comedy, The P-Town Queen.

I watched this unfolding story with great interest. I live in New England and have spent many a long weekend and holiday week enjoying the beaches on Cape Cod. I’m also a fiction writer and Provincetown, the fist at the end of Cape Cod’s arm, is the setting for my romantic comedy, The P-Town Queen.The story revolves around the relationship between a down-on-her-luck shark researcher and a guy who’s hiding from the mob by pretending to be gay. You might think writing such a story involves little more than pulling it from

my overactive imagination and putting it to paper. But fiction, even at its wildest, has to have some basis in reality. If it doesn’t, the reader will soon put down the book (or throw it against the nearest wall, as the case may be) never to pick it up again. So even a fiction writer like me has to do her homework, otherwise known as research. Since my main character, Nikki, was a shark expert, one of the things I researched was great white sharks.

It takes a while for a book to go from bright idea to published entity. In the case of The P-Town Queen, the process took four years, give or take. And what I found in researching sharks off the waters of Cape Cod, four years before publication, was there weren’t many of them. An occasional sighting would cause a blip on the local news, but that was about it. If you were a shark researcher like Nikki, you’d most likely do research somewhere other than Cape Cod, choosing instead a location where there was a large population of sharks to study. The Channel Islands off the coast of California, perhaps. Or the southwestern coast of Australia.

I needed to set my story in Provincetown and so I made up a story line to fit this few-sharks-on-the-Cape fact. Nikki had been researching sharks in California, she lost her grant money and was forced to move home to Cape Cod to live with her retired fisherman father while she figured out how to get more funding and further her career. The story line worked. The book was picked up by Champagne Books and, in June of 2012, it was published.

I needed to set my story in Provincetown and so I made up a story line to fit this few-sharks-on-the-Cape fact. Nikki had been researching sharks in California, she lost her grant money and was forced to move home to Cape Cod to live with her retired fisherman father while she figured out how to get more funding and further her career. The story line worked. The book was picked up by Champagne Books and, in June of 2012, it was published.And in July of 2012, one month after the release, white sharks started appearing off the coast of Cape Cod. There are good reasons for the increase in the white shark population. Grey seals are a protected species and their numbers have been on the rise. Monomoy Island off of the town of Chatham is now home to over a thousand grey seals. White sharks feed on seals, so the greater the food source, the more sharks come around to feed. It does make perfect sense, but I can’t help feeling a little wiz-bang shiver at the co-incidence. I’m sure Nikki would be pleased that the subjects of her research have come to her. Funny, how things work, isn’t it?

White shark image from Wikipedia

Published on November 20, 2013 01:06

November 19, 2013

Alphabetti spaghetti

A few days ago I heard the author Michael Rosen talking on the radio about his new book Alphabetical. He told how the capital letter A turned upside down looked like a stylised ox's head with two horns - and low and behold, this letter used to be called aleph, the word in ancient Semitic languages for an ox. I was hooked and was soon plunging into this exploration of the English alphabet.

A few days ago I heard the author Michael Rosen talking on the radio about his new book Alphabetical. He told how the capital letter A turned upside down looked like a stylised ox's head with two horns - and low and behold, this letter used to be called aleph, the word in ancient Semitic languages for an ox. I was hooked and was soon plunging into this exploration of the English alphabet.Along the way Rosen brings in so many stories. A lot of this is done by a cunning wheeze in the structure. The book is arranged alphabetically (how else?) and each letter starts with a short section on the letter itself, its origins and its uses in English, then follows with a longer section that has a theme. So, for instance, D is for disappeared letters and V is for Vikings. We then get a meandering exploration of that theme - sometimes with many deviations along the way, but always tying back to the alphabet and writing.

It ought to work brilliantly, and in many ways it does, but I was slightly put off by the chunkiness of the book - over 400 pages - and combined with the alphabetic approach, it is difficult not to occasionally have that sense of 'I must plough on to the end' rather than 'I'm enjoying it'. It's that same sense I might get when someone has kindly bought me, say, an encyclopaedia of science fiction and I feel I must my work my way through it from end to end. On the whole it does work, but I couldn't help but feel it might have been better if Rosen had let go of the rather obvious strictures of the alphabet for the book's structure. I think there's an interesting comparison with a couple of books I reviewed once about the periodic table. The one that worked best wove the subject matter into a series of stories with no particular table-related structure. This worked so much better than if the author had worked sequentially through.

However, there is lots to enjoy, from Rosen's impassioned rant against the obsessive use of the systematic synthetic phonics approach in teaching reading these days, to his really interesting observations on the importance of Pitman's shorthand and even his affection for the A to Z (or his knowledge of the absence of the London E19 district). It's a bit like being trapped in a lift with Stephen Fry when he's playing QI host. This is the QI of letters and words.

If you are interested in writing and words - or struggling for a present idea for someone who is - this could be an ideal buy. See more at Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com

Published on November 19, 2013 01:12

November 18, 2013

The invisible truth

I am rather fond of the US TV show Fringe, and am currently working my way through Season 4 (when are we getting Season 5, Netflix?). An episode I watched recently featured an invisible man, which made me think of the difficulties that invisible man syndrome has traditionally revealed in the Science Fiction Hokum Test (SFHT).

The SFHT is a recognition that to make science fiction work it is perfectly acceptable to make up new science or to bend the laws of physics, but once you have set up a premise, it needs to work consistently and logically, or it fails the SFHT.

The original H. G. Wells invisible man (and many in the movies) have had a big problem because their alleged mechanism was a treatment that made our hero transparent. The SFHT says it's fine to invent a mechanism for making someone transparent - but then you have to live with the consequences. And for Wells' invisible man this should have meant going blind. If he had literally become transparent, light would pass straight through his eyes without interacting with them. So there would be no stimulation of the optic nerve - no vision. If, on the other hand, his eyes were allowed some kind of special treatment that prevented this, they would either appear as black holes in space (if they absorbed all light) or floating eyeballs (if they re-emitted photons).

A cuttlefish working its chromatophores for all it's worthThe writers of Fringe escaped this problem by using a different mechanism. Their invisible man, it seems, was endued with chromatophores. These are special pigment-containing organelles found in various creatures that can allow them to change their coloration, most dramatically in the likes of squid and cuttlefish, to provide a remarkably good match to the background they are sitting on.

A cuttlefish working its chromatophores for all it's worthThe writers of Fringe escaped this problem by using a different mechanism. Their invisible man, it seems, was endued with chromatophores. These are special pigment-containing organelles found in various creatures that can allow them to change their coloration, most dramatically in the likes of squid and cuttlefish, to provide a remarkably good match to the background they are sitting on.

Now, SFHT says it's fine to allow this and to overlook all the difficulties of making it work to the extent of making a person invisible. (Apart from getting these alien structures in our skin, they would have to respond much faster than the original, be much more detailed, and be able to pick up a detailed image from the other side of the person, where an actual chromatophore user seems to primarily use information from its eyes.) However, once we have established this, the chromatophores have to act logically and consistently.

You could just about imagine a mechanism for concealing the eyes but leaving them working, though two spots on the back of the head behind the eyes would be visible unless there was a different mechanism for picking up the image from the pupil. But the real problem is with dead stuff. Hair and nails, for instance. Chromatophores have to be in a part of the animal that is alive. For nails this wouldn't be too much of an issue, because they are translucent, so they would produce ripples but be semi-invisible, but hair is a real issue. Doubly so, in fact. All your hair would be visible, and any part of your skin directly opposite a bit of skin shielded by hair would also be visible. It's a massive SFHT fail.

Interestingly the two real bits of invisibility technology echo these two science fiction approaches. The most effective at the moment is simply to put a lot of cameras on one side of the object you want to conceal and a screen on the other. Look at the screen and you see through the object. This is conceptually similar to the approach used in Fringe. At the moment it is an approach that is flawed because your invisibility only works when viewed from a single direction. But it would be surprising if, within a few years, we couldn't produce a spherical shield that consists of a matrix of alternating miniature cameras and LEDs, like those used in LED TV screens. The result is that you would both pick up and transmit an image in any direction - it should produce genuine cloaking.

The other, in some ways more impressive, technology, which you see quite often in the press, is cloaking using metamaterials. These are artificial materials that play around with the way substances interact with light or sound or electromagnetism. Invisibility metamaterials are usually those with a negative refractive index. You'll probably remember from school, refraction is the way light bends as it travels from one medium to another - causing effects like a bending pencil when one is put in a glass of water. Negative refractive index means that the light bends in the opposite way to usual, making it ideal to bend around something and conceal it. Like the original invisible man, with this kind of invisibility, the light never goes through an intermediate electrical signal.

The trouble with existing implementations is that they only work with very small objects and mostly with microwaves rather than visible light. The fact that this is reported in the media as 'Harry Potter style invisibility cloaks created in the lab' reflects the way the media (and university PR departments) can't help wildly exaggerating to get our attention. (A most dramatic example of this recently was the claim that a real Star Wars lightsaber had been made. Headlines literally claimed this. Actually what had been done is linking together two photons so they acted a bit like a molecule of light as they passed through a peculiar substance at near absolute zero. Not exactly a lightsaber.)

The kind of shielding provided by metamaterials, unlike the TV camera version (which doesn't render you blind as you can have inward facing LEDs as well) does suffer from the classic invisible man problem. As the light no longer passes through your pupils, but is deviated around your body, you can't see. Shame really.

So there we have it. You can be invisible and succeed with the SFHT. But very few actual examples in novels, TV and film actually do pass the test.

Image from Wikipedia

The SFHT is a recognition that to make science fiction work it is perfectly acceptable to make up new science or to bend the laws of physics, but once you have set up a premise, it needs to work consistently and logically, or it fails the SFHT.

The original H. G. Wells invisible man (and many in the movies) have had a big problem because their alleged mechanism was a treatment that made our hero transparent. The SFHT says it's fine to invent a mechanism for making someone transparent - but then you have to live with the consequences. And for Wells' invisible man this should have meant going blind. If he had literally become transparent, light would pass straight through his eyes without interacting with them. So there would be no stimulation of the optic nerve - no vision. If, on the other hand, his eyes were allowed some kind of special treatment that prevented this, they would either appear as black holes in space (if they absorbed all light) or floating eyeballs (if they re-emitted photons).

A cuttlefish working its chromatophores for all it's worthThe writers of Fringe escaped this problem by using a different mechanism. Their invisible man, it seems, was endued with chromatophores. These are special pigment-containing organelles found in various creatures that can allow them to change their coloration, most dramatically in the likes of squid and cuttlefish, to provide a remarkably good match to the background they are sitting on.

A cuttlefish working its chromatophores for all it's worthThe writers of Fringe escaped this problem by using a different mechanism. Their invisible man, it seems, was endued with chromatophores. These are special pigment-containing organelles found in various creatures that can allow them to change their coloration, most dramatically in the likes of squid and cuttlefish, to provide a remarkably good match to the background they are sitting on.Now, SFHT says it's fine to allow this and to overlook all the difficulties of making it work to the extent of making a person invisible. (Apart from getting these alien structures in our skin, they would have to respond much faster than the original, be much more detailed, and be able to pick up a detailed image from the other side of the person, where an actual chromatophore user seems to primarily use information from its eyes.) However, once we have established this, the chromatophores have to act logically and consistently.

You could just about imagine a mechanism for concealing the eyes but leaving them working, though two spots on the back of the head behind the eyes would be visible unless there was a different mechanism for picking up the image from the pupil. But the real problem is with dead stuff. Hair and nails, for instance. Chromatophores have to be in a part of the animal that is alive. For nails this wouldn't be too much of an issue, because they are translucent, so they would produce ripples but be semi-invisible, but hair is a real issue. Doubly so, in fact. All your hair would be visible, and any part of your skin directly opposite a bit of skin shielded by hair would also be visible. It's a massive SFHT fail.

Interestingly the two real bits of invisibility technology echo these two science fiction approaches. The most effective at the moment is simply to put a lot of cameras on one side of the object you want to conceal and a screen on the other. Look at the screen and you see through the object. This is conceptually similar to the approach used in Fringe. At the moment it is an approach that is flawed because your invisibility only works when viewed from a single direction. But it would be surprising if, within a few years, we couldn't produce a spherical shield that consists of a matrix of alternating miniature cameras and LEDs, like those used in LED TV screens. The result is that you would both pick up and transmit an image in any direction - it should produce genuine cloaking.

The other, in some ways more impressive, technology, which you see quite often in the press, is cloaking using metamaterials. These are artificial materials that play around with the way substances interact with light or sound or electromagnetism. Invisibility metamaterials are usually those with a negative refractive index. You'll probably remember from school, refraction is the way light bends as it travels from one medium to another - causing effects like a bending pencil when one is put in a glass of water. Negative refractive index means that the light bends in the opposite way to usual, making it ideal to bend around something and conceal it. Like the original invisible man, with this kind of invisibility, the light never goes through an intermediate electrical signal.

The trouble with existing implementations is that they only work with very small objects and mostly with microwaves rather than visible light. The fact that this is reported in the media as 'Harry Potter style invisibility cloaks created in the lab' reflects the way the media (and university PR departments) can't help wildly exaggerating to get our attention. (A most dramatic example of this recently was the claim that a real Star Wars lightsaber had been made. Headlines literally claimed this. Actually what had been done is linking together two photons so they acted a bit like a molecule of light as they passed through a peculiar substance at near absolute zero. Not exactly a lightsaber.)

The kind of shielding provided by metamaterials, unlike the TV camera version (which doesn't render you blind as you can have inward facing LEDs as well) does suffer from the classic invisible man problem. As the light no longer passes through your pupils, but is deviated around your body, you can't see. Shame really.

So there we have it. You can be invisible and succeed with the SFHT. But very few actual examples in novels, TV and film actually do pass the test.

Image from Wikipedia

Published on November 18, 2013 00:16

November 14, 2013

Haynes Death Star Manual

Anyone who has gone through that 'I want to fix up my car' phase in the UK will be familiar with Haynes workshop manuals. These large format hardback books take the reader through all the basic maintenance and fiddly bits for practically every model of car you can think of. Now, they've added a fairly unique bit of maintenance work to their portfolio - fixing up the Imperial Death Star from Star Wars.

Anyone who has gone through that 'I want to fix up my car' phase in the UK will be familiar with Haynes workshop manuals. These large format hardback books take the reader through all the basic maintenance and fiddly bits for practically every model of car you can think of. Now, they've added a fairly unique bit of maintenance work to their portfolio - fixing up the Imperial Death Star from Star Wars.This is one of a range of entertainment-based titles added to the range. I recently reviewed the UFO Investigations Manual , but the Death Star version is closer to originals in the sense of being about a specific piece of technology. Like the UFO book, though, it's a bit of misnomer, in the sense that it isn't actually a workshop manual - it doesn't guide you through maintenance work on a Death Star, but rather it is a book about the Death Star, treating it as if it really existed.

It reminds me in some ways of the sort of thing you used to see in comics like the Eagle when I was young, where you might have a feature on something like the latest steam engine (ahem) or jet fighter or bomber (I remember one on the ill-fated TSR-2) which would inevitably include a cutaway drawing - and here we get several of these on the Death Star in all its glory.

One of the handy things about the whole Star Wars universe, probably only paralleled by Star Trek, is the extent to which back story details have been built up that makes it possible to provide page after page on the technological precursors of the Death Star and the different sections of the vast spaceship (120 km across, in case you wondered). There are plenty of diagrams and also plenty of stills from the Star Wars movies, illustrating different parts of the interior, exterior, and the partly completed second attempt at a Death Star.

Being old and cynical, the faux history and commentaries from the Grand Moff Tarkin amongst others come across as a little forced, but I think for a younger reader these won't prove a problem, and I think any younger fans of the original (and best) Star Wars movies, plus any older types with a sentimental fondness for these films will get a lot of enjoyment out of this. Certainly an excellent stocking filler if you have a big stocking.

You can see more at Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com.

Published on November 14, 2013 00:23

November 13, 2013

The history under our feet

A new guest post by Kate Kelly. Kate is a marine scientist by day but by night she writes SF thrillers for kids. Her debut novel Red Rock, a Cli-Fi* thriller for teens, is published by Curious Fox. She lives in Dorset with her husband, two daughters and assorted pets and blogs at scribblingseaserpent.blogspot.co.uk

A new guest post by Kate Kelly. Kate is a marine scientist by day but by night she writes SF thrillers for kids. Her debut novel Red Rock, a Cli-Fi* thriller for teens, is published by Curious Fox. She lives in Dorset with her husband, two daughters and assorted pets and blogs at scribblingseaserpent.blogspot.co.uk* No, I didn't know either. It stands for Climate Fiction, often dystopian fiction where climate change has had a significant impact on the environment.

GUEST POST

Most of the time you will find me somewhere on the internet talking about writing with my fellow authors, but Brian’s invitation to appear as a guest on his blog has given me the opportunity to talk about my other great passion – geology!

During the day when I’m not writing fiction I work as a marine scientist. I studied first geology and then oceanography at university and both these subjects have remained very close to my heart – especially the geology. And I’m lucky because I am able to indulge this passion – I live on the Jurassic Coast (The southern one – there are two).

What I love so much about geology is the way it influences the landscape around us – it is like the skeleton underneath the fields, determining where the hills persist and the valleys form, the balance between rugged headland and sandy bay. I love the stories it tells of ancient swamps and shallow seas, vast forests and marauding reptiles.

I stood in a quarry once, looking at a rockface - but that rockface was a section through time. I saw the ancient channels where a river once flowed, and the roots of the plants that had grown along its banks – cut off at ground level and singed to carbon by the overlying lava flow – an ancient cataclysm that had destroyed that peaceful valley.

I stood in a quarry once, looking at a rockface - but that rockface was a section through time. I saw the ancient channels where a river once flowed, and the roots of the plants that had grown along its banks – cut off at ground level and singed to carbon by the overlying lava flow – an ancient cataclysm that had destroyed that peaceful valley.I can stand on the beach near my home, sand ripples beneath my boots, and stare at ripples that look just the same, but are millions of years old, frozen into the rocks of the cliff face, reminding me that once before there was a sandy beach on this spot.

The Jurassic coast where I live is, in itself, a section through time. The rocks here span a period of time that straddles the Jurassic on either side.

We start with the Triassic red sandstone cliffs of East Devon, laid down in an ancient desert on the edge of an evaporating sea. We can see the ancient dunes in the cliff face, and find layers of gypsum left behind as what water there was evaporated in the sun.

As we head east the rocks change as the seas encroached, through the Triassic to the life rich seas of the Jurassic proper – ammonites and belemnites teemed in these waters as the occasional icthyosaurus swam by.

Then the seas shallowed to swamp and at Lulworth Cove you can stand on the remains of a fossil forest, giant tree ferns, their roots and stumps now turned to stone.

Then the seas shallowed to swamp and at Lulworth Cove you can stand on the remains of a fossil forest, giant tree ferns, their roots and stumps now turned to stone.Finally the seas encroached once more – the eastern most layers are the chalks exposed at Old Harry Rocks – a deeper sea, these rocks made up of the carbonate shells of tiny plankton.

This is a section of coastline that can give you a broadbrush sweep through time – but if you start to look closer you can see the finer detail of that changing landscape – the local variations – where the land shifted along a fault line – did the Earth shake at that moment? I wonder if it frightened any dinosaurs?

Once there was a desert, then there was a swamp. Now there is a town. I wonder how much of that town will remain for geologists in the future?

Published on November 13, 2013 00:08

November 12, 2013

Thermodynamics 2: the statistics

Last week I started a quick look at the most mind-boggling bit of 'classical' physics, the second law of thermodynamics, one of the stars of my book

Dice World

. This week I'm exploring how the second law can both be true and not true at the same time.

Last week I started a quick look at the most mind-boggling bit of 'classical' physics, the second law of thermodynamics, one of the stars of my book

Dice World

. This week I'm exploring how the second law can both be true and not true at the same time.Thinking of the traditional approach of 'heat flows from hot to cooler', this seemed solid and unbeatable in the Victorian world of brass and iron. And once scientists began to take the idea of atoms and molecules as real entities seriously (something that happened surprisingly late), it also made a lot of sense at the level of individual particles - but there was a twist in the tail.

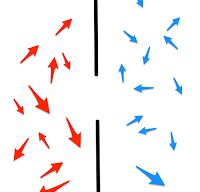

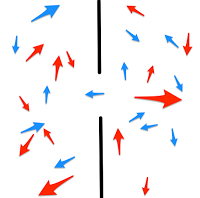

In the beginning was orderA favourite thought experiment for thermodynamicists is a box that is split in two. (They don't get out much, and consider the Large Hadron Collider to be showy and unnecessary.) On one side of the box is a hot gas. On the other side is a cool gas. Life doesn't get much more exciting than this. But wait, it can - because there is a door in the partition separating the two halves.

In the beginning was orderA favourite thought experiment for thermodynamicists is a box that is split in two. (They don't get out much, and consider the Large Hadron Collider to be showy and unnecessary.) On one side of the box is a hot gas. On the other side is a cool gas. Life doesn't get much more exciting than this. But wait, it can - because there is a door in the partition separating the two halves.Let's imagine we could see the individual molecules of the gas, zooming around. (At least a small subset of them.) on the hot side they would be flying about a lot faster than on the cool side. That's what temperature is all about - the energy levels of the molecules. So we open the door and molecules start to swap between sides of the box. After a while, instead of all hot on the left (say) and all cool on the right we will have a mix of hot and cool on the left and a mix of hot and cool on the right. What has happened in macro terms? The hot side got cooler, the cool side got hotter. Heat moved from the hot bit to the cool bit. 'Result!' as our over-excited thermodynamicist might shout.

But soon disorder ruled

But soon disorder ruledIt's worth also looking at this from the point of view of entropy. Entropy, you may remember, is the measure of disorder that is a key to deep thinking about the second law. You could work the change in entropy mathematically, because there is a formula for entropy that is designed for this kind of situation. It's a very simple formula by the standard of modern physics, so I won't apologise for mentioning it. It's:

S = k log WS is the entropy (E was already used up for energy when this equation came along), k is a constant called Boltzmann’s constant and W is the number of ways a system can be arranged to achieve the particular result. (Log is short for 'logarithm'. If you're old enough, you'll know what this is. If you aren't, look it up.) Think of the example of the letters on this web page. If you imagined there are a series of slots on the screen that you can put letters in (think of the old moveable type printing press), then it’s easy to see that there is one way to arrange the letters to get a specific page, but by trying each letter in each slot you could (very slowly) work out W for randomly distributing all the letters and would get a much higher value.

Mostly entropy isn’t about letters on a page but about stuff, and particularly the atoms or molecules that make that matter up. There again, in principle, we can imagine different values for entropy for, say, a crystal where all the atoms have to slot into specific positions and a gas where they’re bouncing all over the place. We couldn’t do the sums exactly – and would have to resort to statistics to get anywhere – but it’s entirely possible to see how entropy applies this way in theory.

As it happens, we don't need to do the maths to see what is happening in terms of entropy with our box. To start with it was relatively ordered because most of the hot (high speed) molecules were on the left and most of the cool (lower speed) molecules were on the right. After a while it is more disordered because each side is a mix of the two. There are more ways to have them in this mixed state than in a state where they are separated. W is bigger. Disorder - entropy - has increased.

Physicists were so impressed with the inevitability of this process that they were prepared to call it a law, and to say that either heat would flow from hot to cold or nothing would happen at all - but that this process would never reverse. Never ever. Not once. And this is where they got a bit of shock when they started to think of the implications of that simple divided box.

Once we are dealing with billions of molecules, flying around randomly, it isn't possible to make a practical prediction of exactly what will happen from moment to moment. Instead we have to rely on statistics, the branch of mathematics that allows us to take an overview of a lot of items simultaneously. And that tells us that, on the whole, the molecules will balance out and we will end up with a mix on both sides. On the whole, W will increase and the entropy will rise. Disorder will rule. But note that 'on the whole' - not every time. Not an unbreakable law. Just a statistical likelihood.

It is entirely possible - though extremely unlikely - that all the hot molecules will happen to head for the left side at the same time, and all the cooler ones to the right. So the system could go from being all nicely mixed up to being separated again. This would mean heat flowing from a cooler region to a hotter one. Entropy would have spontaneously decreased. Remarkably, the second law, despite being so fundamental to the universe working the way we expect it to, is only statistical. It works most of the time. Almost all the time. But just occasionally, over a long enough timescale, it is bound to fail.

The last episode, coming soon, will wrap up the second law with some demonic action.

Published on November 12, 2013 01:02

November 11, 2013

The Young Dictator

There's a certain kind of novel that is technically aimed at 'young adults' (bookseller speak for teenagers), but that is also enjoyed by adults. It is, of course, a publisher's dream if it comes off, as you end up with a much bigger potential audience than usual. The best known example is, of course, the Harry Potter series, though I think my favourite crossover YA books are The Owl Service,

The Night Circus

and Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children, - in fact, demonstrating the power of this approach, they remain among my favourite books ever. I was, therefore, rather interested when I came across a new such book called The Young Dictator by Rhys Hughes.

There's a certain kind of novel that is technically aimed at 'young adults' (bookseller speak for teenagers), but that is also enjoyed by adults. It is, of course, a publisher's dream if it comes off, as you end up with a much bigger potential audience than usual. The best known example is, of course, the Harry Potter series, though I think my favourite crossover YA books are The Owl Service,

The Night Circus

and Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children, - in fact, demonstrating the power of this approach, they remain among my favourite books ever. I was, therefore, rather interested when I came across a new such book called The Young Dictator by Rhys Hughes.The premise is intriguing. Jenny Kahn, a twelve-year-old girl, by strange means, wins a by-election and becomes a member of parliament. With some magical assistance, she ends up as dictator of the UK, which is just the starting point on a career of dictatorship that will involve aliens, giant spiders, a visit to Hell and more. Promising indeed.

The reality is mixed. On the good side, the imagination is unparalleled and often unrestrained, creating some bizarre and wonderful imagery. Although the main character is a touch two dimensional, there is a marvellous character in the form of Gran, an alchemist who claims to have been around in the time of the dinosaurs and is both totally evil and often hilarious. I love a scene early on when Gran is trying to conceal that she is knitting Jenny a rosette so she can stand as an MP. Asked what she is knitting, Gran replies 'An idol.' When questioned further she claims it is a false god to worship upstairs at a shrine she has constructed dedicated to old pagan beliefs. When it is pointed out that she lives in a bungalow, she responds 'Exactly!'

On the downside, the ideas are rather let down by a writing style that is virtually non-existent. We are just told what happens, plonkingly, without any feel for atmosphere or characterisation (apart from Gran). It was rather like reading a book written by a teenager. I was also uncomfortable about the casual lack of morality of practically all the main characters, especially Jenny. She has occasional slight twinges of conscience, but is quite happy for pretty well all the main supporting characters to be massacred in unpleasant fashions, often at her orders. Someone she goes out of her way to rescue, for example, is then crucified. There's also a rather tasteless idea that as a dictator she can join an online service called Fascbook, where she chat to various online friends including Adolf, Benito, Pol Pot and Idi Amin. While I am against any form of censorship, I do wonder if using people who caused such suffering as a comic turn is ideal in a book for teenagers.

I am left, then, in a bit of a quandary. There was certainly much to enjoy in the book, and I happily read on to see what the next exotic idea and weird happening would be, as you may well do too - and Rhys Hughes did not disappoint - but it would have been so much better with a lot of polishing and a big dollop of writing style.

Find out more at Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com

Published on November 11, 2013 00:08

November 8, 2013

The unbearable appropriateness of being Carmina Burana

Anyone who is an aficionado of The X-Factor (or even hears the start of it as they rush out of the room screaming) will be aware of its producers' tendency to use a striking bit of classical music as a background, typically at the beginning and as the judges come on stage. The older members of the audience may recognise it as 'that music they used to have on the Old Spice ad' - not to mention in numerous movies. What it really is, of course, is 'O Fortuna', the opening and closing chorus of Carl Orff's choral masterpiece, Carmina Burana.

Anyone who is an aficionado of The X-Factor (or even hears the start of it as they rush out of the room screaming) will be aware of its producers' tendency to use a striking bit of classical music as a background, typically at the beginning and as the judges come on stage. The older members of the audience may recognise it as 'that music they used to have on the Old Spice ad' - not to mention in numerous movies. What it really is, of course, is 'O Fortuna', the opening and closing chorus of Carl Orff's choral masterpiece, Carmina Burana.What I wonder, though, is whether those involved in the X-Factor know just how appropriate this particular number is, for two reasons, to their peculiar form of entertainment/torture. I suspect not.

The first appropriate aspect is that the chorus is about the wheel of fortune in the sense of the random hand of fate meaning that at one moment we might be on top and the next on the way down. Spookily accurate. But even more interesting is the second aspect, which used to really depress me as a student.

I first came across Carmina Burana when we performed it in a concert at my college music society, and it rapidly became one of my favourite pieces. But this didn't stop me finding the ending, in my idealistic student fashion, rather unpleasant. The second half of the piece is largely the story of a seduction, with the antepenultimate section being an electrically soaring climax from the soprano soloist. We then have the penultimate section, Ave Formosissima, celebrating love to a rising, uplifting ending... which crashes into the final, grinding repeat of O Fortuna. The message is clear. You go through this apparently life-changing experience and afterwards the world goes on and everything is just the same.

I have to say I find it less depressing now (perhaps because as an older person I am more accepting that this is a realistic rather than a cynical view). But oh how it should resound for those X-Factor entrants who tell us that they don't want to be a cleaner or a van driver or whatever it is anymore. And the judges, putting them through, tell them 'You can say goodbye to all that.' But actually the Carmina Burana music is much more honest. They might be going through an apparently life-changing experience, but afterwards, for most of them, the world will be exactly the same.

I really would encourage you to listen to this clip to hear that transition from affirmation to inevitability. It is quite spine tingling:

Published on November 08, 2013 00:43

November 6, 2013

A new brand of revolution

Like many, I watched online the interview between the UK's leading political interviewer, Jeremy Paxman and comedian Russell Brand with interest. It brought out, as has quite frequently been the case over the last few years, the way that Brand is not just an idiot who can offend people on radio programmes and/or a sex addict - he is very verbally able, and has thought about things in what is, admittedly, a rather shallow, but nonetheless interesting fashion.

Like many, I watched online the interview between the UK's leading political interviewer, Jeremy Paxman and comedian Russell Brand with interest. It brought out, as has quite frequently been the case over the last few years, the way that Brand is not just an idiot who can offend people on radio programmes and/or a sex addict - he is very verbally able, and has thought about things in what is, admittedly, a rather shallow, but nonetheless interesting fashion.I can certainly see why Brand could get many rallying to his cry that politicians don't do anything for us and that democracy is flawed. But there is a real problem with Brand's approach to politics - and it is reflected all too often in the over-the-top, knee jerk political comments I frequently see on Twitter and Facebook. It's a problem that is often reflected in protest movements - they're against something, or everything (think capitalism, conservatives, politicians, America, big business, corporations whatever) - but they don't actually offer a better alternative.

We know from practical experience that Marxism does not of itself offer a great alternative to capitalism. I'd go further - for the vast majority, Marxism proved far worse than capitalism. It's all very well to slag off democracy and capitalism, but be very wary what you wish for. Because the alternatives have so far always been a disaster.

So I'm sorry, until the likes of Mr Brand can come up with a constructive alternative that will deliver a better life for everyone, I'm sticking with democracy and capitalism. Of course it's flawed. Of course some people do better from it than others - and some of them deserve to have the smug smiles wiped off their faces. But simply posturing on TV and using big words, attacking the status quo without offering any suggestion of how to improve things, does nothing for politics and nothing for the human condition. I'm afraid Russell Brand's revolution would simply make things worse.

In case you didn't catch it, here it is:

Published on November 06, 2013 23:58

Coming over all thermodynamic

My book Dice World about randomness and probability and their impact on our lives inevitably includes quantum theory, but some have expressed surprise that it also covers the second law of thermodynamics. After all, popular science books are supposed to be about modern, trendy, weird science, aren't they? And that sounds so old and Victorian. I mean, 'thermodynamics'. It just reeks of steam engines. And that's certainly why it was first of interest - but the second law is just as fascinating as anything that the twentieth or twenty-first centuries have thrown at us, and this is the first of a short series of posts pondering it.

My book Dice World about randomness and probability and their impact on our lives inevitably includes quantum theory, but some have expressed surprise that it also covers the second law of thermodynamics. After all, popular science books are supposed to be about modern, trendy, weird science, aren't they? And that sounds so old and Victorian. I mean, 'thermodynamics'. It just reeks of steam engines. And that's certainly why it was first of interest - but the second law is just as fascinating as anything that the twentieth or twenty-first centuries have thrown at us, and this is the first of a short series of posts pondering it.The second law is a classic of physics, so much so that it inspired the physicist Arthur Eddington's famous lines:

If someone points out to you that your pet theory of the universe is in disagreement with Maxwell's equations - then so much the worse for Maxwell's equations. If it is found to be contradicted by observation - well these experimentalists do bungle things sometimes. But if your theory is found to be against the second law of thermodynamics I can give you no hope; there is nothing for it but to collapse in the deepest humiliation.The more common way of looking at the second law in modern times is in terms of entropy, a measure of the disorder in a system, but I want to start with the original, steam engine driven approach. This says approximately that in a closed system, heat will move from a hotter part of the system to a cooler part. If it didn't, we could have lots of fun. We could build a perpetual motion machine. All you would need is to get that heat flowing the wrong way, make use of it to power the machine, then send it back to be used again. Simples. We can also think of it as saying that in a closed system disorder stays the same or increases; it does not decrease.

But the universe seems to have a downer on perpetual motion machines, and doesn't allow the second law to be broken. Except when it does. Because one of the reasons that the second law is so fascinating is that, though it is such a fundamental aspect of the workings of reality there are ways that it can be broken - or bent. The true flaw in the law I'll come back to another time, but let's explore the classic bending beloved of creationists. Because it's easy to read the law as 'heat flows from hot places to cold' or that 'disorder stays the same or increases.' Yet this is patently not always true.

Take a refrigerator. That starts with something that is cold and makes it colder still. It takes heat from a relatively cold place (inside the fridge) and sends it somewhere warmer (outside). Surely Eddington should be turning in his grave. Or there's the argument of our creationist friends. They say that the second law proves the existence of God. Why? Because disorder has clearly decreased on the Earth. You might not think this is the case when you listen to the news, but here we are talking about the order and disorder in stuff. In the early years of the Earth's formation everything was pretty random. But over time molecules have been organised into all kinds of complex systems. There is much more order in the world than there used to be. And that, say the creationists, is evidence of God's hand at work.

The reason for this apparent discrepancy is that we aren't allowed to cherry pick with science. We can't just take a bit of a scientific theory that we like and ignore the rest. And that's exactly what is being done here. In both the fridge and the disorder on Earth examples we are ignoring the words 'in a closed system.'

Scientists like closed systems. They are imaginary boxes in which something takes place that are isolated from everything outside. They make things simple for the scientists - but they are often not very realistic. Think of my specific examples. The second law only works in a closed system because otherwise energy can come in from outside and drive things the opposite way. And that's exactly what happens here. The refrigerator isn't a closed system - we have to pump power into it to get the cooling to happen. Similarly, the Earth gets vast amounts of energy from the Sun - plenty to deal with its ability to create order from disorder.

So the second law is bent - but only if you read it wrong.

I want to leave you with one disconcerting thought, though. There are no closed systems, with the possible exception of the universe (and we don't know that for sure). None whatsoever. For example, you can't stop gravity. There is no box to prevent it influencing a system. Of course you can counter it various ways, notably through acceleration, but that isn't the same thing as saying that you are isolated from it. Closed systems are useful approximations to the real world, a tool that physicists rely on to make understanding ridiculously complex things amenable. But they aren't real. It's easy to think of scientists as being very precise people - and they are. They love their error bars. But that precision comes at a price, and it's one that sometimes catches everyone out.

More on the second law another time, where we will see how it can be broken entirely - and the role of a demon in exploring it.

Published on November 06, 2013 00:46