Brian Clegg's Blog, page 111

September 24, 2013

Will the real economics step forward?

Traditional economics is a fantasy. It is about as relevant to the real world as orcs, wizards and fire-breathing dragons. Which makes it a trifle worrying that politicians put such dependence on it.

Traditional economics is a fantasy. It is about as relevant to the real world as orcs, wizards and fire-breathing dragons. Which makes it a trifle worrying that politicians put such dependence on it.The big problem with old-style economics is that it thought of human beings as perfect actors who always took the best possible action to maximise return. It is only ridiculously recently that some economists have realized that this is not a realistic picture and have launched the discipline of behavioural economics, which makes the rather more realistic assumption that people will make decisions based on all whole host of factors, not just maximizing return - and that they often get things wrong. Really, behavioural economics should be renamed 'economics' while what used to be called economics becomes 'fantasy economics', but I think economists are too embarrassed to do this (especially as they would have to rename a lot of their Nobel prizes 'fantasy Nobel prizes').

Most of the books on behavioural economics to date have been either textbooks or popular science books like Dan Ariely's Predictably Irrational , but what businesses are crying out for is practical business books that help a company make use of behavioural economics - exactly what Enrico Trevisan sets out to do in The Irrational Consumer (noticing a trend in the titles here?). It is subtitled 'applying behavioural economics to your business strategy' just to underline this.

The result is a partial success. Trevisan does tell us lots of interesting things about behavioural economics within the context of business transactions. But this title doesn't work as a practical business book. There are three reasons for this. One is that it is written like a dull academic textbook. You often have to read a sentence two or three times to grasp what it is trying to say. Here's a sentence genuinely picked at random: 'Many critical aspects of this approach to the market and to the client are now widely known, such as the balance between dis-homogeneity and tractability of the various segments, the instability of these over time, their responsiveness to external deciding factors, the limited duration in time of the characteristics, and so on - these are some of the more evident methodological questions.' Still awake? I thought not.

It's a shame because when Trevisan is talking about real world examples he suddenly becomes lucid and readable, but unfortunately the majority of the book is written in that verbose, difficult to digest style.

The second problem is that there is no real attempt to make this a practical how-to book. He describes the impact of behavioural economics on, for instance, the decision a customer makes in choosing a product. But there is no practical guidance on what to do about this, how to use it to make your business better. So there is really no delivery on that subtitle - it doesn't give any guidance on business strategy.

Finally there is a questionable assumption. Trevisan tells us that this approach could be use either to help customers to make better decisions or to make use of the understanding of their economic processes in order to maximize profits from them. He decides rather arbitrarily that we should be doing the selfless thing and helping the customer to get it right for them, because this will lead to better long term relations. While in principle with some customers and some products this is true, it is a big assumption, and it certainly isn't aways the case. So I am afraid we really do need the missing chapter 'How to screw every last penny out of your customers using behavioural economics.'

Overall, then, you will learn a lot by reading this book, but sadly it will be considerably harder work than it should have been, and what you learn will not include direct, practical things to do.

You can see more at Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com.

September 23, 2013

Why scientists need philosophy

Trainee scientists in their natural habitatThere has been something of an argument raging in the science world. This may seem surprising when we often portray scientists as cold calculating types, but of course there is every bit as much backbiting and antagonism there as in any other competitive discipline. The dispute seems to be between those who think that science has flaws that should be widely understood, and those who think they should be swept under the carpet.

Trainee scientists in their natural habitatThere has been something of an argument raging in the science world. This may seem surprising when we often portray scientists as cold calculating types, but of course there is every bit as much backbiting and antagonism there as in any other competitive discipline. The dispute seems to be between those who think that science has flaws that should be widely understood, and those who think they should be swept under the carpet.There seem to be three prime points of argument. What science does, whether one can dare to question Richard Dawkins (probably the most heinous of the three in some people's eyes) and whether it is acceptable to equate science with religion.

Before looking at these points in a little more detail, I think it's telling that those who seem to think science is beyond criticism are primarily biologists. I suspect this is because biology has only been a proper science for such a short time. Pre-Darwin, I think few could argue with Rutherford's telling jibe, largely aimed at biologists, that 'all science is either physics or stamp collecting.' For many biologists, science is a fervently believed truth. Physicists have had to live through the traumatic 20th century when most of our best-loved theories (think Newton's laws of motion, for instance) were shown to be wrong or at best inaccurate. For that reason, even though I love relativity as it stands, I accept that it may be necessary to replace it with something better if we are to get a working theory of quantum gravity. Biologists rarely have this perspective.

So, first let's take the biggie. What science does. It might seem obvious that scientists would understand this, but all the evidence is that many don't. When, for instance, Stephen Hawking pronounced there was no more need for philosophy, he was demonstrating his own ignorance of the nature of science, because we need philosophy of science to understand the role. And what is that? Scientists build models that predict outcomes that match what is observed in the world. Over time those models have got better - some, including the modified versions of evolution, are superb. But it is pure ignorance to say that science is about truth or about describing reality. All science can do, and it does it very well (and nothing else will ever do it as well), is produce models which are a good match to the observed outcomes of reality.

As shorthand, scientists tend to speak as if their theories are the truth. It's easily done. I've done it myself when speaking about the big bang, say, because it's too clumsy to do otherwise in a few words. But when writing a book about it, I am careful to emphasize that this is just our best theory at the moment based on the data we have at the moment. It isn't the only theory, it may easily be disproved by new data, but it is the best we have at the moment. And given that it is the best, why would you want to say anything else is 'true'? But equally you have to be aware of what you are doing if you say the big bang is what happened. Because there is no basis for doing that.

The second problem is over Richard Dawkins' approach. Dawkins is a great science writer. I love his science books. But he seems to have no understanding whatsoever of psychology, which means he was an extremely poor Professor for the Public Understanding of Science. Dawkins probably puts more people off science than any fundamentalist religious preacher. He has made so many insulting remarks about people who disagree with him that he inevitably puts people off science before they get a chance to look at the evidence. I am always reminded of a remark Dawkins is alleged to have made to someone before a TV programme about psi phenomena. 'Don't you want to look at the evidence?' he was asked. 'I'm not interested in evidence,' Dawkins is said to have replied.

Which neatly leads me on to the third point about whether science can be equated with religion. It is certainly true that when scientists assert that science is 'the truth' (and quite possibly 'the way and the light') or, like Dawkins, scientists say they are not interested in evidence, then science is opening itself up to the accusation of acting like a religion. And the kind of attack that all too often comes whenever anyone dares to suggest science is fallible just shows how much that 'must not be questioned' part is true.

I think a rational scientific (!) assessment of science must come up with the understanding that it has a lot in common with religion. It has one huge benefit over true religions, in that it has a mechanism for disproving things which (on a good day) it considers more important than the established body of writing, but there are certainly many similarities. After all, science is a belief system. It is by far the best belief system, but all of us, even working scientists, have to take 99.99% of science on trust. We have to believe what other people tell us, because we can't go and check whether or not what they say or write is true. If any biologist does not agree with this, I would ask them how they personally would check to see if the evidence supports the existence of the Higgs boson to the p levels advertised.

Operationally, science is not a religion, but there are many (again, more biologists than from any other discipline) who treat it with religious fervour and who take what might be considered a fundamentalist attitude. Like most religionists don't understand the nature of religion, so these scientific fundmentalists don't understand the nature of science.

What it is important to do is to accept that there are ways that science gets it wrong. It doesn't stop science being wonderful. It doesn't stop science being the only way to get a better understanding of how the world behaves. It doesn't stop science being essential both for expanding pure knowledge and in the way it feeds technology and medicine. But pointing out the flaws is not heresy, it is important for an understanding of science. Those who can't accept this are not being scientific about science. They are pretending things are not the way they are. And people who do that really don't deserve to call them selves scientists.

Image from Wikipedia

September 20, 2013

Feeling sorry for Farage

The Farage in questionI am not a natural supporter of Nigel Farage, head of the UK Independence Party. The Party's politics put my back up in a big way - it tends to be small minded and altogether too Daily Mailish. Farage himself comes across to me as rather creepy - not at all the 'jolly guy down the pub' image that he puts forward. But after a piece on Channel Four News last night, I feel I have to defend the man.

The Farage in questionI am not a natural supporter of Nigel Farage, head of the UK Independence Party. The Party's politics put my back up in a big way - it tends to be small minded and altogether too Daily Mailish. Farage himself comes across to me as rather creepy - not at all the 'jolly guy down the pub' image that he puts forward. But after a piece on Channel Four News last night, I feel I have to defend the man.About the first 15 minutes of usually excellent C4N yesterday was dedicated to what I presume was an exclusive 'scoop' that while Farage was at school (the rather posh, definitely not 'man down the pub', Dulwich College) many of the teachers didn't like him, mostly because of his right wing leanings, and there was a concerted effort to try to prevent him being a prefect because of this. It was even alleged that during a residential trip, he and friends walked through a sleepy village singing 'Hitler Youth songs.'

I'm sorry, but this isn't fair. Firstly the songs business, put forward as the most extreme example. It just doesn't ring true. How many teenagers in the 1980s would know Hitler Youth songs? Farage makes the point that he wouldn't know them, and frankly I agree. And taking the situation as a whole, I think it's both unfair to throw someone's teenage political experimenting at them (how many Labour politicians dabbled with communism as a youth over the years?), and I also agree with Farage's suggestion that much of this was just rebelliousness/a wind up.

The reason I have some sympathy is that when I was a similar age, I was standing on a railway station platform (Levenshulme if you must know) with several other people from my school. It was one of those stations where a lot of fast trains pass through without stopping. At the suggestion of one of our group (not me), when we saw a train coming, we all lined up on the platform and did a Nazi salute to the passing train. Let's be clear here. This did not indicate anything whatsoever about our political leanings. The sole aim was to do something offensive, because that's what teenage boys in a group sometimes do when they egg each other on. We might equally have mooned at them, had we been more daring.

I'm not defending what we did. It was stupid and puerile. But that's the whole point. Young people sometimes do offensive things purely for the sake of it. Farage was at what seems to have been a school with quite a left-leaning attitude, and to take the kind of stance he did would have been a natural act of rebellion. It doesn't indicate anything either way. And it's certainly not worthy of 1/4 of a major news programme.

Image from Wikipedia

September 19, 2013

The power of Free

I'm currently reading the book The Irrational Consumer for review here in this very blog (I expect the review to appear in a few days). The rather attractive idea is that this is a business book that makes use of our irrational approach to economics to improve customer relations. (The author specifically declines the alternative approach, which is to make use of our irrational approach to economics to rip

I'm currently reading the book The Irrational Consumer for review here in this very blog (I expect the review to appear in a few days). The rather attractive idea is that this is a business book that makes use of our irrational approach to economics to improve customer relations. (The author specifically declines the alternative approach, which is to make use of our irrational approach to economics to rip off our customers. What a nice chap.)

Something I'd come across before, but still has such a dramatic impact that it is worth repeating here is the power of free. Don't worry if you aren't in the business of selling things to people - it is still fascinating, if only as a way to think about your own rationality, or lack of it, when faced with economic decisions.

The example given is an experiment undertaken by Ariely in 2008 where a series of participants were offered a choice between a quality praline at 15 cents and a mass produced chocolate at 1 cent. I personally think this is a slightly risky experiment because chocolate is such a personal taste. I, for instance would rather have a piece of cheap Cadbury chocolate than anything the Lindt 'chocolatiers' can whip up in their workshops. However, let's ignore that foible.

When the experiment was done 73 percent went for the fancy chocolate and just 27 percent went for the cheap and cheerful option. But then the experiment was repeated, with the praline at 14 cents and the mass produced chocolate free. Now just 31 percent went for the praline and 69 percent for the less sophisticated product. Yet the price differential between the two was exactly the same. The majority were prepared to pay 14 cents more for the quality product as long as the cheap one cost just 1 cent, but make the cheapo option free and there was a scramble to lay their hands on it.

The fact is, people are suckers for 'free' and we should never forget this. However it is an approach that has to be tempered with some concerns. If you offer something for free, then start to make a large charge for it, people are less inclined to take it up than if the new charge is relatively small, or if the same large charge follows a fairly sizeable introductory price. We easily get into the mindset of something being free and then resist paying the more sizeable prices. This is probably an argument for not making books free, but rather selling them at a low price (e.g. 99p) for a brief introductory period, even though you miss out on the attraction of free.

Perhaps the best thing, if possible, is to keep the basic item free but have a premium version (the so called freemium model), so you don't get that unfortunate comparison of 'this was free for the first year but now I'm paying through the nose'.

September 18, 2013

This online shopping surely won't catch on

I still remember the early days of Amazon, when a lot of people cast doubt on its ability to become profitable. After all, it was argued, we like to get our hands on goods, to look at them and touch them, before we buy. How said people must be feeling silly now.

It's not that we have turned our backs in visiting physical shops. You only have to head down to Swindon's designer outlet centre at the weekend to realize this isn't the case. But for those at work, most shops simply don't operate in the hours when they want to go shopping. If you've a 9 to 5 job, then you can shop before 9 or after 5. So when do shops open? Often 9 to 5.30. Clever thinking, guys. Is it too much of a surprise then that people turn to online retailers, where they can shop where and when they like?

Convenience has to be a major part of the argument. In our last house, where the nearest supermarket was 20 minutes drive away, we almost always had our groceries delivered. Now I've a massive 24 hour superstore 5 minutes walk away we are much more likely to just pop over and get what we need when we need it. Town centres hardly help with this by charging for car parking, so not only have we to take time to get there, we have to pay to park. Is it surprising that customers head for out of town or online shopping?

Online stores have a big disadvantage because you can't see the goods before you buy them - but they make up for this with their convenience of access and by trying to provide superb customer service. If bricks and mortar shops want to keep going they should build on the advantage of presence by seeing how they can improve their access and get much better at how they treat their customers. That way, they could still give the Amazons of this world a run for their money.

September 17, 2013

Get it right, BBC

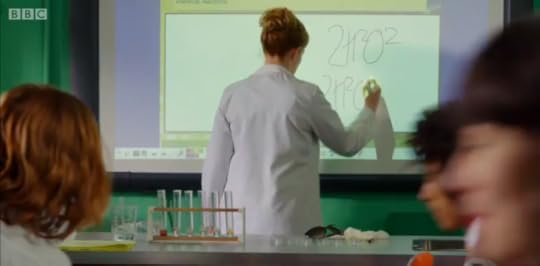

What is she doing? It seems she has invented a new kind of hydrogen peroxide that is made up of H-squared and O-squared. I have no idea what a squared atom is, and I wait with interest to see the BBC's drama department explaining all about these new particles. At the very least, I would expect a squared atom would enable us to perform cold fusion.

In the meanwhile I just don't understand what kind of editing process at the BBC can allow H2O2 to be written as H2O2. I can only assume every single person involved didn't even manage to get a science GCSE. And that says something very sad about the whole TV drama world.

September 16, 2013

How very different from the home life of our own dear animals

In my long project to digitize old photos I've just done some from my first visit to London in 1963. My mum was taking her teaching finals, so my dad took me away for three days in the capital. I have to say, as a father-son bonding exercise it was brilliant. We had a great time, staying in a (rather scruffy) hotel in Russell Square, eating in a brilliant Italian restaurant (the first time I'd ever come across raffia-covered bottles and candles that dripped wax down over their bottle supports - actually, the first time I'd eaten Italian food) and seeing all the usual sights.

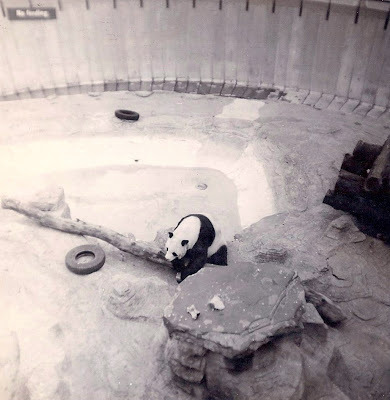

In my long project to digitize old photos I've just done some from my first visit to London in 1963. My mum was taking her teaching finals, so my dad took me away for three days in the capital. I have to say, as a father-son bonding exercise it was brilliant. We had a great time, staying in a (rather scruffy) hotel in Russell Square, eating in a brilliant Italian restaurant (the first time I'd ever come across raffia-covered bottles and candles that dripped wax down over their bottle supports - actually, the first time I'd eaten Italian food) and seeing all the usual sights.But what really caught my eye looking at the photos was not the guards at the Tower of London or the other famous buildings, it was a couple of pictures from a visit to London Zoo. At the time there were two animals that were by far the most famous in the land, Chi Chi the panda and Guy the gorilla, both were based in Regent's Park. I have photos of each of them and what stands out to me is how appalling the conditions were that these animals were kept in.

Remember these were the best known, star animal attractions in the whole country. Even up in the wilds of Rochdale I knew both of them by name. Yet we see Guy in a featureless concrete cell and Chi Chi, while at least given some space and a tyre, still in a stark, concrete environment with no attempt to make it feel like nature.

Remember these were the best known, star animal attractions in the whole country. Even up in the wilds of Rochdale I knew both of them by name. Yet we see Guy in a featureless concrete cell and Chi Chi, while at least given some space and a tyre, still in a stark, concrete environment with no attempt to make it feel like nature.I think it is worth taking a look at these just to see how much the whole zoo business has come on since my youth. There are those who doubt the benefits of zoos, but I think on the whole they do serve a useful purpose, both in terms of education/increasing interest in zoology and in breeding programmes. But when you see those photos there can be little doubt at all that we have got a whole lot better at it since the swinging 60s.

I can't help wonder what zoologists of the time were thinking. It's hardly rocket science to realize that a gorilla, say, is not going to be happy in an environment like that. It's not a matter of animal rights, it would be enough to have a concern for the wellbeing of your specimens. Looking back, it boggles the mind.

September 12, 2013

Is there a law of the excluded middle?

I have just finished reading the excellent

Inventing Reality

for review, a great book that both outlines the essentials of physics and looks into what physics is really doing. It has a fascinating argument about the law of the excluded middle, which I just have to pass on.

I have just finished reading the excellent

Inventing Reality

for review, a great book that both outlines the essentials of physics and looks into what physics is really doing. It has a fascinating argument about the law of the excluded middle, which I just have to pass on.The law of the excluded middle essentially says that a statement must be either true or false. Apart from tricksy statements like 'This statement is false', most mathematicians and all physicists seem to assume that this is true, that a statement has to be either true or false. But is really the case?

Bruce Gregory uses a simple, and apparently non-tricksy statement as an example. Here's a conjecture: 'A woman will never be elected president of the United States of America.' Is that true or false? As Gregory says, 'if we insist it must be one or the other, we seem to be committing ourselves to a future that somehow already exists, for the truth or falsity of the statement depends on events that have not yet occurred.'

Just think about that for a moment. We can certainly say it is very likely that there will be a woman president elected at some point in the future, but I can also posit a range of scenarios where it never comes to pass. We can't say that this statement is definitely true or false. And if that's the case, argues Gregory, might it not also be true of a mathematical conjecture, like the Goldbach conjecture (saying that every even number larger than 2 can be written as the sum of two primes)? Obviously this could be proved false, all we need to do is come up with a single even number that isn't the sum of two primes, but it is entirely possible that the conjecture will never have a definitive outcome.

The same, Gregory suggests, could be true of some aspects of physics. We can't assume that, say, String theory will ever be proved true or false. (Where 'true' or 'false' does not mean matches reality, as we have no idea what reality truly is. Rather it means 'successfully predicts measurable outcomes'.) Which makes for some interesting thinking about physics, the universe and everything.

September 11, 2013

Better bikes

And, of course, like many others I have witnessed far too many bad practices from bikes. (If you are a biking enthusiast, don't get on your high horse - er, saddle - I see plenty of bad practices from drivers too, but I am talking about bikes here.) The majority in these parts seem to think it's okay to ride at night without lights. I've seen bikes riding three-abreast, totally blocking the carriageway. And I've pulled out at a T-junction traffic light only to have a bike ram into the side of me because he thought traffic lights didn't apply to him.

There's no doubt that bikes do irritate motorists - and a lot of it is down to fear. Drivers genuinely don't like going near bikes because they are aware of the damage they could cause.

Our bike-friendly footpathRound our way, we have a much better solution. Almost all our pavements are bike/pedestrian. And it works. There is no danger of knocking a bike over when you are driving, because they aren't on the road. Of course there is always a risk from mixing bikes and pedestrians, but in my experience round here, the bikes are fairly careful (in part because these clearly aren't pure bike lanes) and though I have seen a few near misses I'd rather see a bike/pedestrian collision than a car/bike one.

Our bike-friendly footpathRound our way, we have a much better solution. Almost all our pavements are bike/pedestrian. And it works. There is no danger of knocking a bike over when you are driving, because they aren't on the road. Of course there is always a risk from mixing bikes and pedestrians, but in my experience round here, the bikes are fairly careful (in part because these clearly aren't pure bike lanes) and though I have seen a few near misses I'd rather see a bike/pedestrian collision than a car/bike one.I ought to stress that our pavements are not mega-wide, two lane, bike ways. They are just ordinary pavements - perhaps slightly wider than some, but not hugely so. There is no doubt this approach could be taken in many more places. And maybe it would even save some lives.

September 10, 2013

Why today's time machines don't disappear

I love giving talks about the science of time travel as a result of

Build Your Own Time Machine

- and I can't help but feel there will be a few more as we lead up to the 50th anniversary of Doctor Who in November. I usually start by pointing out that there is nothing in the laws of physics that prevents time travel. In fact it's happening all the time. The best manmade examples? Voyager 1 has travelled 1.1 seconds into the future, while the GPS satellites constantly slip into the past. Often people don't believe me - and they have a good, if invalid, reason for this disbelief.

I love giving talks about the science of time travel as a result of

Build Your Own Time Machine

- and I can't help but feel there will be a few more as we lead up to the 50th anniversary of Doctor Who in November. I usually start by pointing out that there is nothing in the laws of physics that prevents time travel. In fact it's happening all the time. The best manmade examples? Voyager 1 has travelled 1.1 seconds into the future, while the GPS satellites constantly slip into the past. Often people don't believe me - and they have a good, if invalid, reason for this disbelief.The thing is, when a time machine moves into the future or the past it disappears, doesn't it? The Tardis does, and so did H. G. Wells' time machine. But Voyager and the GPS satellites stubbornly insist on still being there. This is because it's something fiction gets wrong. Most time machines don't disappear as they travel through time. Let's take a look at those two examples, but exaggerate the effect to see what's going on.

We'll start with the simpler one, travelling into the future. Anything that moves has a time stream that slows down compared with the place it is moving with respect to. So when, for instance Voyager 1 flies away from the Earth, its time runs slower. This is a well tested and inevitable effect of special relativity. So let's imagine that Voyager 1 travels much closer to the speed of light than it actually does. And now we use a magic telescope that allows us to see from the Earth into Voyager 1, so we can watch its clock. We would see the clock running incredibly slowly. When a year has passed by on the Earth, perhaps just a second has ticked past on the clock. So after 10 years, just 10 seconds has passed by on the probe. If Voyager 1 arrived back at the Earth at this point, it would have moved 10 years into Earth's future.

Now here's the thing. For that whole 10 years we still see Voyager 1 - we just see its clock ticking past very slowly indeed. It doesn't disappear, we continue to see it. But hang on, you might say, this is cheating. Voyager isn't really moving into the future, it just looks like that because its clock seems to be running slowly. But this isn't a 'seems to be' (as it is sometimes described even in popular science books). From the Earth's viewpoint that clock really is running slowly. As is everything else on board. If Voyager was much bigger and had a crew then the people on the ship will only have aged 10 seconds and experienced 10 seconds passing by. They really have travelled into the future.

(If you are wondering why time only slows on the ship, you are a clever person. Special relativity works both ways. From the ship's viewpoint, the Earth is moving away at high speed, and to anyone on Voyager, time on the Earth seems to run slowly. But the situation isn't symmetrical. The ship undergoes acceleration at both ends of its trip that the Earth doesn't, and it is this acceleration that means the ship experiences something different to the Earth.)

So to the more unlikely aspect of time travel. Because heading off to the future doesn't risk any strange paradoxes, but should you travel into the past, surely all those funny things like killing your parents before you are born can happen? Let's take a look at the GPS satellite.

The satellite is moving, so seen from the Earth, just like Voyager 1, the satellite's time runs a bit slower because of special relativity. But there is a second effect here which operates in the opposite direction and is more significant. General relativity shows us that gravity slows time down. The stronger the gravitational field, the slower time runs. So time runs faster on the GPS satellite than it does on the Earth. The opposite effect to Voyager 1, so the satellite moves into the future. Again, let's imagine the (tiny) effect is hugely exaggerated and every second that passes on Earth, a year passes on the satellite. So after 10 seconds passes on the Earth, the satellite is pretty well 10 years ahead. Once more, if we watch the satellite travel through time, we don't see it disappear. We just see its clocks run really quickly.

So let's finish the time voyage. On the satellite, say, it is 2023, while it is 2013 on the Earth. So the satellite pops down to Earth and moves ten years into the past. Whizzo magico. Only here's the thing - it can't move back before it was first set up, because time doesn't go backwards on the Earth, it just runs very slowly from the satellite's viewpoint. So it can't go back into the past (or peer down at Earth and discover next week's lottery results) or do something that will effect the future, because the Earth's future hasn't happened yet. The future it has moved from is its own. Like Voyager, it might seem that this cheating, but it really isn't. For instance, if people lived on that GPS satellite, in the 10 seconds that elapsed on Earth, they could do 10 years of work and bring back with them newly written novels etc., bringing them from the future to the past. They just couldn't get up to any tricksy paradoxes.

If you find this all rather disappointing, there is a third class of time machine where you would disappear, and where paradoxes are possible. These are the ones depending on wormholes, neutron star cylinders and the like which won't be around for millions of years and may never be possible to construct. But you shouldn't be disappointed by what is possible now, because we still have the amazing fact that both backward and forward travelling time machines exist today.