Brian Clegg's Blog, page 115

July 10, 2013

Science, girls, statistics - what could go wrong?

The use of statistics by the media is something that constantly drives me round the bend. (At least, it does 90% of the time.) Now the BBC has wound me up by combining science, gender issues and, yes, statistics.

To be fair these are not blatant errors, but rather that hoary old standard, not being scrupulous about separating correlation and causality. As we saw with the infamous high heels and schizophrenia study, even academics can be prone to this, but the media does it every day. One very common example is where they tell us on the news that the stock market went up or down as a result of some event. Rubbish. In most circumstances the stock market is far too chaotic a system to attribute a change to an event that happened around the same time. It's guesswork and worthless.

Here, the misuse is slightly more subtle. 'Girls who take certain skills-based science and technology qualifications outperform boys in the UK, suggest figures' says the relatively mild headline. But is this really what the figures say, and if so what should we deduce?

According to exam publisher Pearson, girls who take BTECs in science and technology are more likely than boys to get top grades. Now here's a key sentence. According to the BBC 'Despite this success, girls are vastly outnumbered by boys on these courses.' The implication here is that this is just the tip of the iceberg, and with many more girls we would have lots of better grades. The suggested correlation is of gender with good grades. However it could equally well be that this is self-selection, a regular plague on the houses of those attempting to interpret statistics. If there are large numbers of boys on the courses, many of them could be there because 'that's what boys do' not because they have any talent for the subject. By contrast, if there are a small number of girls (in this case between 5 and 38% depending on topic), then they are likely at the very least to have greater than average enthusiasm, and quite possibly greater talent. If this is the case, all this is saying is that 'better than average female candidates do well compared with average male candidates.' Not quite such a strong story - in fact not a story at all.

The article then goes on to quote someone saying too few girls take STEM subjects. Now, I think this is true. We still have an artificial cultural bias about girls going in for science and it is wrong. However, what we mustn't do is to try to support the belief that this is wrong with data that doesn't contribute anything to the argument. By putting the 'girls are better at it' supposed statistic alongside the desire to have more girls in the subject implies that there is something inherent in the gender that makes girls better at it, so we want more of them. No, no, no. We want more because girls should have the same opportunities, because they shouldn't be put off science/tech because their peers think it's inappropriate. Not because a dubious interpretation of stats implies we could improve the quality of our STEM stock of students because girls are better at it. Without effective evidence this is just as sexist as saying girls shouldn't do science because it's too difficult for their little brains.

A girl and a science building. See, they can go together! *One last example from the article. We have a quote from Helen Wollaston of Women into Science and Engineering saying the results prove "that girls can do science, IT and engineering." That's a silly thing to say. Firstly there is nothing to prove. Why would they not be able to? But also, as we've seen, all these results seem to show is that the most motivated girls are better than the average boys. There should be no need to use dubious statistics to 'prove' that girls can do STEM. I don't think anyone has doubted this since we stopped thinking (as they genuinely once did) that these subjects would overheat delicate female brains. What we need to prove is that far more girls can be interested in STEM and that we can change the culture so that it is cool for them to do so. That is a totally different issue - but it is the real one we face.

A girl and a science building. See, they can go together! *One last example from the article. We have a quote from Helen Wollaston of Women into Science and Engineering saying the results prove "that girls can do science, IT and engineering." That's a silly thing to say. Firstly there is nothing to prove. Why would they not be able to? But also, as we've seen, all these results seem to show is that the most motivated girls are better than the average boys. There should be no need to use dubious statistics to 'prove' that girls can do STEM. I don't think anyone has doubted this since we stopped thinking (as they genuinely once did) that these subjects would overheat delicate female brains. What we need to prove is that far more girls can be interested in STEM and that we can change the culture so that it is cool for them to do so. That is a totally different issue - but it is the real one we face.

* In the interest of openness and scientific honesty, I ought to point out that the woman portrayed was a music student.

To be fair these are not blatant errors, but rather that hoary old standard, not being scrupulous about separating correlation and causality. As we saw with the infamous high heels and schizophrenia study, even academics can be prone to this, but the media does it every day. One very common example is where they tell us on the news that the stock market went up or down as a result of some event. Rubbish. In most circumstances the stock market is far too chaotic a system to attribute a change to an event that happened around the same time. It's guesswork and worthless.

Here, the misuse is slightly more subtle. 'Girls who take certain skills-based science and technology qualifications outperform boys in the UK, suggest figures' says the relatively mild headline. But is this really what the figures say, and if so what should we deduce?

According to exam publisher Pearson, girls who take BTECs in science and technology are more likely than boys to get top grades. Now here's a key sentence. According to the BBC 'Despite this success, girls are vastly outnumbered by boys on these courses.' The implication here is that this is just the tip of the iceberg, and with many more girls we would have lots of better grades. The suggested correlation is of gender with good grades. However it could equally well be that this is self-selection, a regular plague on the houses of those attempting to interpret statistics. If there are large numbers of boys on the courses, many of them could be there because 'that's what boys do' not because they have any talent for the subject. By contrast, if there are a small number of girls (in this case between 5 and 38% depending on topic), then they are likely at the very least to have greater than average enthusiasm, and quite possibly greater talent. If this is the case, all this is saying is that 'better than average female candidates do well compared with average male candidates.' Not quite such a strong story - in fact not a story at all.

The article then goes on to quote someone saying too few girls take STEM subjects. Now, I think this is true. We still have an artificial cultural bias about girls going in for science and it is wrong. However, what we mustn't do is to try to support the belief that this is wrong with data that doesn't contribute anything to the argument. By putting the 'girls are better at it' supposed statistic alongside the desire to have more girls in the subject implies that there is something inherent in the gender that makes girls better at it, so we want more of them. No, no, no. We want more because girls should have the same opportunities, because they shouldn't be put off science/tech because their peers think it's inappropriate. Not because a dubious interpretation of stats implies we could improve the quality of our STEM stock of students because girls are better at it. Without effective evidence this is just as sexist as saying girls shouldn't do science because it's too difficult for their little brains.

A girl and a science building. See, they can go together! *One last example from the article. We have a quote from Helen Wollaston of Women into Science and Engineering saying the results prove "that girls can do science, IT and engineering." That's a silly thing to say. Firstly there is nothing to prove. Why would they not be able to? But also, as we've seen, all these results seem to show is that the most motivated girls are better than the average boys. There should be no need to use dubious statistics to 'prove' that girls can do STEM. I don't think anyone has doubted this since we stopped thinking (as they genuinely once did) that these subjects would overheat delicate female brains. What we need to prove is that far more girls can be interested in STEM and that we can change the culture so that it is cool for them to do so. That is a totally different issue - but it is the real one we face.

A girl and a science building. See, they can go together! *One last example from the article. We have a quote from Helen Wollaston of Women into Science and Engineering saying the results prove "that girls can do science, IT and engineering." That's a silly thing to say. Firstly there is nothing to prove. Why would they not be able to? But also, as we've seen, all these results seem to show is that the most motivated girls are better than the average boys. There should be no need to use dubious statistics to 'prove' that girls can do STEM. I don't think anyone has doubted this since we stopped thinking (as they genuinely once did) that these subjects would overheat delicate female brains. What we need to prove is that far more girls can be interested in STEM and that we can change the culture so that it is cool for them to do so. That is a totally different issue - but it is the real one we face.* In the interest of openness and scientific honesty, I ought to point out that the woman portrayed was a music student.

Published on July 10, 2013 01:03

July 9, 2013

How to build a Star Trek transporter

Randomness and probability are at the heart of my book

Dice World

and they are also fundamental to quantum theory, which is why I spend some time on the subject in the book. One of my favourite aspects of quantum theory is quantum entanglement (I wrote

The God Effect

on the subject), which is responsible for a number of interesting technical developments including a small-scale version of the Star Trek transporter.

Randomness and probability are at the heart of my book

Dice World

and they are also fundamental to quantum theory, which is why I spend some time on the subject in the book. One of my favourite aspects of quantum theory is quantum entanglement (I wrote

The God Effect

on the subject), which is responsible for a number of interesting technical developments including a small-scale version of the Star Trek transporter.Think for a moment of what’s involved in such a technology. On Star Trek, the transporter appears to scan an object or person, then transfers them to a different location. This was done on the TV show to avoid the cost of the expensive model work that was required at the time, before the existence of CGI, to show a shuttle landing on a planet’s surface. But it bears a striking resemblance to something that is possible using entanglement.

To make a transporter work, we would have to scan every particle in a person, then to recreate those particles at a different location. There are two levels of problem with this. One is an engineering problem. There are huge numbers of atoms in a human body – around 7 × 1027 (where 1027 is 1 with 27 zeros following it). Imagine you could process a trillion atoms a second. That’s pretty nippy. But it would still take you 7 × 1015 seconds to scan a whole person. Or to put it another way, around 2 × 108 years. 200 million years to scan a single person. Enough to try the patience even of Mr Spock.

Assuming, though, we could get over that hurdle – or only wanted to transport something very small like a virus – there is a more fundamental barrier. What you need to do to make a perfect copy of something is to discover the exact state of each particle in it. But when you examine a quantum particle, the very act of making a measurement changes it so that you can't make a copy. It isn’t possible to simply measure up the properties of a particle and reproduce it. However, quantum teleportation gives us a get-out clause.

There is a slightly fiddly process using entanglement that means we can take the quantum state of one particle and apply it to another particle at a different location. The second particle becomes exactly what the first particle had been in terms of its quantum properties. But we never discover what the values are. The entanglement transfers them without us ever making a measurement. Entanglement makes the impossible possible. This has been demonstrated many times in experiments that range from simple measurements in a laboratory to a demonstration that used entanglement to carry encrypted data across the city of Vienna.

Even if we were able to get around the scanning scale problem, though, it’s hard to imagine many people would decide to abandon cars or planes and use a quantum teleporter for commuting. Bear in mind exactly what is happening here. The scanner will transfer the exact quantum state of each particle in your body to other particles at the receiving station. The result will be an absolutely perfect copy of your body. It will be physically indistinguishable, down to the chemical and electrical states of every atom inside it. It will have your memories and will be thinking the same thoughts. But in the process of stripping those quantum properties, every atom of your body will have been scrambled. You will be entirely destroyed in the process. As far as the world is concerned you will still exist at the remote location – but the original ‘you’ will be disintegrated.

I think I'll stick with the train.

Published on July 09, 2013 01:19

July 8, 2013

In memoriam

I know a couple of (fairly elderly) people who are terribly worried about the format of their own funerals. One, particularly, has about half a dozen sheets of paper scattered around friends and relations, giving precise instructions over which hymns will be sung, what organ music played, what readings read, burial or cremation and all the rest. She has gone for such redundancy because she is very worried that someone will lose the instructions and the funeral won't be as she wants it to be. Frankly, my dear, I don't give a damn. And I don't know why anyone else does either.

I know a couple of (fairly elderly) people who are terribly worried about the format of their own funerals. One, particularly, has about half a dozen sheets of paper scattered around friends and relations, giving precise instructions over which hymns will be sung, what organ music played, what readings read, burial or cremation and all the rest. She has gone for such redundancy because she is very worried that someone will lose the instructions and the funeral won't be as she wants it to be. Frankly, my dear, I don't give a damn. And I don't know why anyone else does either.In the end, a funeral is for those left behind, not for the deceased. Whether you believe the individual concerned has gone to heaven or is simply dead and gone, either way, they aren't there to appreciate the finer points of the service, or get irritated if the organist uses the wrong tune for 'Guide me O Thou Great Redeemer.' (It should be Cwm Rhondda, of course.)

I similarly have no understanding of why families get so upset when, say, an internal organ of a loved one has been retained in a lab by accident and they go to all the trouble of having it interred in the grave. It's not the person. Why worry? A bit of a body isn't a person. (Taken to the extreme, we would collect hair and shed skin and nail clippings too.)

I can only assume my attitude, which clearly is not the norm, comes from a combination of being very mildly on the autistic spectrum, combined with family tradition. Neither of my parents have a grave. Nor do my father's parents. If I wanted to commune with them after death, I would want to go somewhere that meant something to them, somewhere special - or to touch something they were very fond of. As far as I am aware, neither of my parents had an affection for cemeteries, nor for gravestones, so why should I go to such a place, or talk to such to a piece of stone they never saw?

It's not for me to say that other people should be the same as me, especially on such a strongly felt topic, but I really, genuinely don't understand what all the fuss is about. It's not that I don't understand how traumatic it is to lose a loved one - of course I know why that is a big deal, and with both my parents dead, I have experienced the pain of loss firsthand. But I don't understand the obsession with laying down details of your own funeral, or worrying about where a loved one's body or ashes are interred.

We say to children when preparing them to face a coffin, 'It's not the person, it is just what is left behind.' But we don't seem to believe the message ourselves.

Published on July 08, 2013 00:13

July 5, 2013

Spaceflight epiphany

We need more of thisWhile 'Spaceflight Epiphany' sounds like it should be a NASA project, it is actually an account of my personal experience. I've had a big change of heart on the value of getting people into space.

We need more of thisWhile 'Spaceflight Epiphany' sounds like it should be a NASA project, it is actually an account of my personal experience. I've had a big change of heart on the value of getting people into space.For many years I have subscribed to the view, supported by many scientists, that putting people in space is a painful waste of money. A manned mission costs vastly more than automated probes, which means there is much less money available to do the science. We have got most of our valuable scientific knowledge about the universe from the likes of Hubble, WMAP and Planck, not from Space Shuttle and the ISS.

Nobel Prize-winning physicist Steven Weinberg points out the way that a major science project, the Superconducting Super Collider (SSC), was abandoned because the funds went instead to the International Space Station (ISS). The SSC would have been significantly more powerful than the Large Hadron Collider at CERN, and would have achieved results a good ten years earlier. This would have been a major step in major science research.

By comparison, ten times as much money has been spent on the ISS as was due to go to the SSC, but it has yielded nothing of scientific value. All the useful space science, Weinberg points out, has been done using unmanned satellites. “In the days of the cold war,” Weinberg commented, “perhaps it really was important to America to be the first country to put a man on the Moon and not let it be Russia, but today I think that really is irrelevant. The United States is not now in competition with any country resembling the Soviet Union and we do not need to show we are technically just as competent as they are. Any argument of national prestige that could have been valid in the 1960s is certainly not valid 50 years later."

At the moment I am writing my next book, which is about space exploration, and in doing so I have recaptured some of the excitement I felt during the Apollo mission - the same excitement that provides part of the reason for loving science fiction like Star Trek or James Blish's Cities in Flight series. The 'epiphany' word reflects my belief that Weinberg is wrong.

It's true that with a few exceptions, like the Shuttle mission that fixed the problems with the Hubble Space Telescope’s mirror that initially rendered it useless, humans have contributed a negligible amount of the scientific value of space missions. But, much though I love science, life (and specifically space exploration) is not all about the science. Scientists inevitably overvalue the scientific component of any activity, but in reality there is more to life – and in the case of manned space exploration, more to making life worth living.

The fact is that manned space exploration - and I mean going back to the Moon, to Mars, to the asteroids... even one day to the stars, not messing about in the ISS, as far away from Earth as Boston is from Philadelphia - is one of humanity's greatest achievements and really is worth doing for its own sake. It may be corny, but all that final frontier stuff really is true. We should be out there, exploring, pioneering, indulging our curiosity. Because it's what we do best.

And if we stop, we lose a part of our humanity.

Image from NASA via Wikipedia

Published on July 05, 2013 00:23

July 4, 2013

Government, meet real business

The logo of my company, Creativity Unleashed.

The logo of my company, Creativity Unleashed.How about it, government? Unleash a bit of creativity...Every now and then I get really irritated with the government. I know this is not exactly news, nor uncommon. I can never remember a time when everyone was saying 'Isn't this government wonderful, aren't we lucky to have these excellent people in charge?' I think the time we've come closest in the UK in recent years was in the honeymoon period of the Blair government, and even then there were some whinges (not to mention, no doubt, moans from the likes of my friend Henry Gee, who believes that the world will one day recognize that Boris Johnson is the greatest statesman who has ever lived). But the thing of which I am complaining today is not a feature of any particular government. They all do it.

I think I have moaned about this before, but it requires regular revisiting. I just get absolutely furious when the government tells us that the only way to get more people in employment is for companies to create more jobs - and tries to use the tax system and other blunt instruments to encourage this.

I am not saying there is anything wrong with companies creating jobs, I'm all for it. But what gets me angry is that there is no recognition of the millions of people who aren't a burden on the taxpayer, in fact contribute to taxes, and yet don't have an employer. Yes, I'm talking about the army of the forgotten, the self-employed. For me this is by far the best way to work and many more people should do it. Admittedly it's not for everyone, I accept that. Some need the psychological and financial safety net of a 'real job' - though many have found over the years that this 'safety net' is anything but secure. However, I do wish that the government would stop ignoring what a significant part of the economy we self employed are.

I don't employ anyone - and I don't want to employ anyone. Ever. If I need extra resources I will subcontract the work to someone, but in all my experience (and at BA I managed some big teams), having employees is a nightmare, both in terms of red tape and in all the responsibilities you take on by employing someone. But all the incentives the government keeps pumping out to get us to employ people seem to miss out on the fact that we should be encouraging and helping people to start up for themselves. Because then everyone benefits. I have not had an employer since I left BA in 1994, but I have contributed to the economy in plenty of ways, as do most of the self-employed.

Everything the government does seems to be focussed on big business and against self-employment. Even their statistics are biassed this way. A lot of what I do - probably about half of my income - is a kind of export. But because I'm not shipping boxes of widgits through customs, I suspect it never shows up on the government statistics. Because I'm a nonentity in their eyes.

Come on governments. Get wise to the hidden sector of the economy. Instead of more and more incentives to employ people, how about making it more beneficial to be self-employed? I pay you taxes - I even collect taxes for you in the form of VAT. Now give a little back. You know it makes sense.

Published on July 04, 2013 00:40

July 3, 2013

Eddie the eagle

Apparently this is Eddie, though he sounds much

Apparently this is Eddie, though he sounds muchbetter than he looksWe have some great radio broadcasters in the UK, particularly on BBC Radio 4, but I think in many ways the unsung hero of the breed is Eddie Meyer who presents the 5pm news magazine PM.

What Meyer has, and I think it is fair to say none of his colleagues have to the same degree, is a wry sense of humour that comes through strongly, even though the programme can be covering mostly serious issues.

There was a wonderful example a week or two ago, which inspired this post. Meyer had mistakenly referred to Istanbul as the capital of Turkey (we all know it is Ankara, don't we folks?) - he apologised for this, which is fine. But then demonstrated why he is so brilliant.

A little while later he was introducing a reporter who was at a technology event in San Francisco. 'Now we're going to Bill Bloggs,' Meyer said (or words to that effect), 'reporting from San Franciso, the capital of Turkey.' No time for a double take, it's straight on to the item. But to the Meyer fan, it was a classic example of his genius. I honestly can't think of another serious current affairs reporter who would think of, or get away with, doing this. Genius.

Next Honours List, how about a gong for Eddie? He deserves it.

Image from Wikipedia

Published on July 03, 2013 01:43

July 2, 2013

Where science meets woo

In my latest book,

Extra Sensory

, I look at whether there is a scientific basis for the likes of telepathy, telekinesis, remote viewing and precognition. When I tell people I've written this (and will be selling books at the Seriously Strange event), particularly those from the science community, there is often a sharp intake of breath. 'You don't want to get yourself involved with that stuff,' they say. I understand the response, but I think they are wrong.

In my latest book,

Extra Sensory

, I look at whether there is a scientific basis for the likes of telepathy, telekinesis, remote viewing and precognition. When I tell people I've written this (and will be selling books at the Seriously Strange event), particularly those from the science community, there is often a sharp intake of breath. 'You don't want to get yourself involved with that stuff,' they say. I understand the response, but I think they are wrong.It is easy to see why there is that sharp intake of breath. In a Facebook discussion of my book, where someone had generously recommended it, before long others were contributing with information about 'chi/qi' and even 'quantum healing.' There is a tendency to lump a lot of things together, not all of which sit comfortably with science. However this rather misses the point of what I'm trying to do with the book.

First of all I make the clear distinction of only considering the paranormal, not the supernatural. By this I mean I am looking at abilities that are outside our current understanding, but could have a natural, scientific explanation. So, for instance, I don't cover spirit mediums, whose claims are definitely supernatural. There is a grey area - ghosts, for instance, seen as the manifestation of dead people would be supernatural, but if they were instead a physical phenomenon (like the old 'stone tapes' idea) they could be examined as paranormal. However, I thought it best to draw the line as safely as possible and excluded them too.

What I then set out to do was to see if I could come up with an potential mechanisms for, say, telepathy to work, and to examine the evidence from the quite extensive academic work that has been done to try to discover and test such abilities. It is a fascinating, if frustrating tale, because it contains some very dramatic characters (Uri Geller, who gets a whole chapter, springs to mind) and an awful lot of fraud, bad science and statistical pitfalls.

There are examples of all three, for example, in the most famous early academic work by J. B. Rhine in the 1930s. Rhine did vast numbers of experiments, mostly for telepathy and clairvoyance. But there were clear examples where fraud could easily have taken place. Rhine used some very sloppy experimental conditions. Perhaps worst, of all, he had a tendency to misuse the statistics. A classic example is where Rhine comments on a particularly successful run 'The probability of getting 15 straight successes on these cards is (1/5)15 which is one in over 30 billion.' This is falling into the trap known as cherry picking.

You can see the problem with what Rhine is doing by comparing it with a similar response to a lottery winner. Last week someone in the UK won the Euromillions jackpot. The probability of doing this is 1 in over 116 million. Okay, not quite the same as Rhine's number, but impressive enough. However, we don't conclude that either the winner was clairvoyant, or that he or she cheated. Because there wasn't a single entrant. And similarly, by using that '1 in over 30 billion' number, Rhine was picking out a single set of results, based on the values of those results, from many thousands of attempts. This is, at best misleading.

I think it is important to take an unbiassed look at the paranormal that is neither a simple dismissal of evidence (there's a wonderful quote from Rupert Sheldrake, where he was to be in a TV show with Richard Dawkins and Dawkins is alleged to have said 'I don't want to discuss the evidence'), nor blind acceptance of woo. This is partly because so many people have experienced something that may be paranormal, but also because I don't believe it is scientific simply to say 'I would never look at something,' if it could have a physical explanation, dismissing it without considering the evidence.

You can get Extra Sensory as a hardback or a Kindle ebook from amazon.co.uk and amazon.com (and it is, of course, available from bookshops and in other ebook formats).

Published on July 02, 2013 00:57

July 1, 2013

Letting off steam

Between the ages of six and my late teens I spent many of my summer Sunday afternoons playing with trains. You may be thinking at this point 'No wonder he's such a nerd, he should have been out in the fresh air,' but actually I was outside at the time. Because this was no attic train set.

One of my first solo drives, not trusted yet with passengers. The engine

One of my first solo drives, not trusted yet with passengers. The engine

is Lancashire Lad, one of the smaller models, but always among my

favourites as it was easy to drive and very reliable.My dad was a model engineer - his hobby was building these stunning working model steam locomotives. No 0 or 00 gauge here - we are talking 3.5 and 5 inch wide track, plenty big enough to carry 10 passengers behind. As part of the Rochdale Society of Model and Experimental Engineers (by its website, still going strong), most Sundays we would toddle up to Springfield Park where the society's track was and indulge in a wondrous time.

Of course my favourite activity was driving. The controls are very similar to the real thing, with the added complexity that you also have to do the fireman's job as well as driving, frankly the harder of the two. This involved keeping the fire at the right level - not too hot, but not damped down with too much coal, and the delicate job of balancing the water supply, tweaking the bypass so that you kept the boiler at just the right level. It was brillant, particularly when your passengers were a string of squealing girls.

To be fair, driving was a luxury. I wasn't allowed to do it until I was 10, and was usually limited to one hour's session (though I might get another in if I was lucky), but I also enjoyed being on the ticket booth, managing the platform, and even being on the dirty end, starting engines from cold (the smell of paraffin soaked charcoal used to get the fire started, and the whine of an electric blower, still brings this all rushing back) and raking out the ashes and cleaning them down after a shift. I even played in the park sometimes.

I suspect there were long boring bits and lots of rain-stops-play - we tend to forget those. But in the joyous recreation of memory it was always a sunny day with a couple of engines in steam and the sound of the whistle and the squeals as one of the trains rattled into the tunnel echoing in my ears.

One of my first solo drives, not trusted yet with passengers. The engine

One of my first solo drives, not trusted yet with passengers. The engineis Lancashire Lad, one of the smaller models, but always among my

favourites as it was easy to drive and very reliable.My dad was a model engineer - his hobby was building these stunning working model steam locomotives. No 0 or 00 gauge here - we are talking 3.5 and 5 inch wide track, plenty big enough to carry 10 passengers behind. As part of the Rochdale Society of Model and Experimental Engineers (by its website, still going strong), most Sundays we would toddle up to Springfield Park where the society's track was and indulge in a wondrous time.

Of course my favourite activity was driving. The controls are very similar to the real thing, with the added complexity that you also have to do the fireman's job as well as driving, frankly the harder of the two. This involved keeping the fire at the right level - not too hot, but not damped down with too much coal, and the delicate job of balancing the water supply, tweaking the bypass so that you kept the boiler at just the right level. It was brillant, particularly when your passengers were a string of squealing girls.

To be fair, driving was a luxury. I wasn't allowed to do it until I was 10, and was usually limited to one hour's session (though I might get another in if I was lucky), but I also enjoyed being on the ticket booth, managing the platform, and even being on the dirty end, starting engines from cold (the smell of paraffin soaked charcoal used to get the fire started, and the whine of an electric blower, still brings this all rushing back) and raking out the ashes and cleaning them down after a shift. I even played in the park sometimes.

I suspect there were long boring bits and lots of rain-stops-play - we tend to forget those. But in the joyous recreation of memory it was always a sunny day with a couple of engines in steam and the sound of the whistle and the squeals as one of the trains rattled into the tunnel echoing in my ears.

Published on July 01, 2013 00:31

June 28, 2013

Civil engineers? Nice chaps!

A long time ago, in a galaxy that bore a distinct resemblance to the Milky Way, I co-authored a book on business creativity called

Imagination Engineering

. It did quite well and it still sells today. This was when my colleague Paul Birch and I were first setting up giving training in creativity, and the main purpose of the book was to be the guide to our method. It described our approach to stimulating ideas and solving problems.

A long time ago, in a galaxy that bore a distinct resemblance to the Milky Way, I co-authored a book on business creativity called

Imagination Engineering

. It did quite well and it still sells today. This was when my colleague Paul Birch and I were first setting up giving training in creativity, and the main purpose of the book was to be the guide to our method. It described our approach to stimulating ideas and solving problems.Something we thought that might be useful was to give some sort of simile or metaphor that would help us to describe and encourage the process of producing an enhancing ideas. We wanted it to be something that was all about pioneering, about boldly going and all that kind of thing. So we hit on the simile of civil engineering, saying our approach to creativity was like being the first to build roads and railways and structures out in a new and unexplored land.

To be honest, we don't use the simile anymore, as it got in the way more than it helped. One of the essential learning points of creativity is that you will fail sometimes. It's all part of the creative process. (Which is why politicians struggle so much with anything creative - they can only see failure as being a disaster. I think it is because they played too many competitive sports at school.) So that wasn't a problem - in fact it has helped us refine the approach.

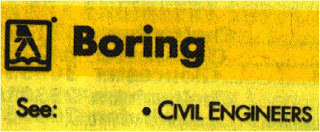

Even so, the simile is still there in the book, which is why we were initially rather disconcerted, but then delighted to discover this in Yellow Pages:

Of course, the civil engineers we had in mind were the pioneering kind, not the kind that lay sewer pipes in Surbiton high street. But even so it was a salutary reminder that not everyone views things the same way. That was a genuine entry, by the way. It disappeared after a few years, presumably as a result of complaints from the Institute of Civil Engineers or some such body.

I wonder, has Yellow Pages or its equivalents ever carried any equally entertaining accidental comments on the topic advertised?

Published on June 28, 2013 01:39

June 27, 2013

It's a fraction but my fraction

The way most of use computer programs makes sledgehammers and nuts a minor infringement on the 'getting the scale right' tally. Our requirements are orders of magnitude simpler than the programs' ability.

Take Audacity, the impressively free audio editing program I use. It can do all sorts of exciting things. Just look at that huge menu of effects of which I use... one. The program comes in hugely useful when I edit the tracks recorded for my company's increasingly vast emporium of organ pieces and hymn accompaniments, but my routine is always the same. Read in a track, make sure the lead in and out are consistent times, wipe any audio before the playing, fade out the audio at the end. And save. Touching a tiny part of the application's capabilities.

Take Audacity, the impressively free audio editing program I use. It can do all sorts of exciting things. Just look at that huge menu of effects of which I use... one. The program comes in hugely useful when I edit the tracks recorded for my company's increasingly vast emporium of organ pieces and hymn accompaniments, but my routine is always the same. Read in a track, make sure the lead in and out are consistent times, wipe any audio before the playing, fade out the audio at the end. And save. Touching a tiny part of the application's capabilities.

Though it's not so extreme most of us also have a limited repertoire in more familiar programs, whether it's an office suite like Word, Excel and Powerpoint, or image manipulation. Just like Audacity, the image editor I use, Pixelmator, has vast power - it's rather like Photoshop without the diamond encrusted price tag. But I only ever use a tiny fraction of it.

So some people think that the answer is pared down, super-efficient programs that just do the essentials. The Mac world is littered with writing apps, for instance, many of which boast that they only provide the basics, clearing away clutter, helping you concentrate on the task at hand.

But therein lies the rub. What is the task? What are the basics? Because, while I only use a few features of Word, they are my features. The features that are important to me. I've been involved with PCs since the very beginning and many of the early word processors didn't have a word count feature. It simply didn't occur to the developers - why would anyone want to know how many words there are in a document? And that was fine from their viewpoint. In fact most business users don't really care. But if you are a writer there are two certain facts. First, you need a word processor. Second, it needs to be able to do a word count.

As a writer you don't need most of the fancy layout abilities. When someone asks me how to do a page border or why fancy table layouts aren't working I hoot with amusement. I don't care. These aren't my features. But for others, they are essentials.

So next time you hear someone moaning about 'feature bloat' and how ridiculously over-complex applications are, and how the developers need to get back to basics, raise a quizzical eyebrow. 'Yes, but whose basics?' you should say. And feel suitably smug.

Take Audacity, the impressively free audio editing program I use. It can do all sorts of exciting things. Just look at that huge menu of effects of which I use... one. The program comes in hugely useful when I edit the tracks recorded for my company's increasingly vast emporium of organ pieces and hymn accompaniments, but my routine is always the same. Read in a track, make sure the lead in and out are consistent times, wipe any audio before the playing, fade out the audio at the end. And save. Touching a tiny part of the application's capabilities.

Take Audacity, the impressively free audio editing program I use. It can do all sorts of exciting things. Just look at that huge menu of effects of which I use... one. The program comes in hugely useful when I edit the tracks recorded for my company's increasingly vast emporium of organ pieces and hymn accompaniments, but my routine is always the same. Read in a track, make sure the lead in and out are consistent times, wipe any audio before the playing, fade out the audio at the end. And save. Touching a tiny part of the application's capabilities.Though it's not so extreme most of us also have a limited repertoire in more familiar programs, whether it's an office suite like Word, Excel and Powerpoint, or image manipulation. Just like Audacity, the image editor I use, Pixelmator, has vast power - it's rather like Photoshop without the diamond encrusted price tag. But I only ever use a tiny fraction of it.

So some people think that the answer is pared down, super-efficient programs that just do the essentials. The Mac world is littered with writing apps, for instance, many of which boast that they only provide the basics, clearing away clutter, helping you concentrate on the task at hand.

But therein lies the rub. What is the task? What are the basics? Because, while I only use a few features of Word, they are my features. The features that are important to me. I've been involved with PCs since the very beginning and many of the early word processors didn't have a word count feature. It simply didn't occur to the developers - why would anyone want to know how many words there are in a document? And that was fine from their viewpoint. In fact most business users don't really care. But if you are a writer there are two certain facts. First, you need a word processor. Second, it needs to be able to do a word count.

As a writer you don't need most of the fancy layout abilities. When someone asks me how to do a page border or why fancy table layouts aren't working I hoot with amusement. I don't care. These aren't my features. But for others, they are essentials.

So next time you hear someone moaning about 'feature bloat' and how ridiculously over-complex applications are, and how the developers need to get back to basics, raise a quizzical eyebrow. 'Yes, but whose basics?' you should say. And feel suitably smug.

Published on June 27, 2013 00:50