Brian Clegg's Blog, page 110

October 8, 2013

Replica shirt rant

Okay, I haven't had a good rant in a while, so batten down the hatches, me hearties.

Okay, I haven't had a good rant in a while, so batten down the hatches, me hearties.I hate seeing men, especially paunchy middle-aged men, in replica football shirts. To me it is both incomprehensible and stomach-churning.

It's different with children. If we can accept seeing our children dressed up as Power Rangers, say (that's what it was in my children's day - substitute current alternative), there's no reason why they shouldn't also dress up as football players. But grown men do not have the excuse of fantasy play.

Why on earth do they shell out as much as £50 for a shiny replica of a match shirt, and then wear it to go shopping at the supermarket, or for a pint down the pub? It looks hideous. This is a uniform, designed for a specific purpose - it simply doesn't work as a casual shirt. And they don't make it any better by either having a real player's name or their own on the back of the shirt.

I also question why they feel the need to wear these things. I admit I have a disadvantage in trying to understand this as I have absolutely no interest in watching sport, and none of the tribal togetherness that would make me want to join in by wearing my team's fancy dress costume. I simply don't get it. But I appreciate that lots of people do - even so, it's hard to see what they feel they are getting out of wearing their wannabe shirts, apart from looking an absolute prat. Surely, I can but hope, they don't think that somehow it gives them some of the player's athleticism and vigour. Watching the shirt slither its way over their pot-bellies really doesn't give this effect.

These shirts are naff, over-priced and pointless. Instead of buying next season's shirt, they should get themselves a decent bit of casual wear and give the remaining 50% of what otherwise would have been profit for the money grubbing companies to charity. Or stick it on the lottery. Or in a savings account. Anything, in fact, rather than wearing that ridiculous tat.

Rant over. Sigh.

Published on October 08, 2013 05:47

October 7, 2013

About About Time

At the weekend we went to see About Time, the latest rom-com from Richard Curtis. Not my typical movie fare, but it did involve time travel in what was, in a very subtle way, a remake of Four Weddings and a Funeral. There will be spoilers, but I will give plenty of warning of their arrival if you haven't seen it.

At the weekend we went to see About Time, the latest rom-com from Richard Curtis. Not my typical movie fare, but it did involve time travel in what was, in a very subtle way, a remake of Four Weddings and a Funeral. There will be spoilers, but I will give plenty of warning of their arrival if you haven't seen it.I'm quite happy to watch this kind of thing as brainless entertainment, but when it enters my territory I expect a little rigour in the time travel, which wasn't entirely present. Even so, I recognize this is fiction, and at that it is fantasy, not science fiction, so I am prepared to give it more leeway than, say, Looper . True science fiction time travel, using technology, started with H. G. Wells' The Time Machine, but About Time belongs to an older tradition, where the trip takes place effectively by magic, whether it's as a dream or, as in Mark Twain's famous time travel book, by being hit on the head.

In About Time, the magic is achieved by going into a cupboard, clenching the fists, and thinking of a time and place. Fair enough, I say - I'm quite happy to watch a fantasy movie, as long as the plot is consistent, and that's where I think Curtis falls down a little. I'll explain why after the spoiler break, but before I do, I ought to say there's a reason I call it a remake of Four Weddings and a Funeral. It's not just that it has a tongue-tied middle class British male main character (who sounds remarkably similar to Hugh Grant in the voice-over narration, but thankfully comes across as less of a twit in his character) and a more together American female main character. There actually are four weddings and a funeral - though the weddings are subtly concealed.

±

±

±

±

SPOILER ALERT

±

±

±

±

Don't read any further if you haven't seen the film and want to see it

±

±

±

±

SPOILER COMING UP

±

±

±

±

The problem I have with the time travel is that even fantasy should be logically consistent. Curtis sets up the very clever dilemma of 'have another child or be able to visit your late father', but then totally demolishes the reasoning for there being a dilemma. Supposedly the idea is that when the MC went back and fixed his sister's life, his baby changed from a girl to a boy, because it only takes subtle differences in the environment to result in a different sperm getting through. So he goes back and unfixes things for his sister and low and behold his child is back to the way she was. But actually the influence of any surrounding action like the sister business would be far lower than the simple subtle difference in physical conditions at the moment the egg was fertilised. He still wouldn't get the same combo. It couldn't be fixed.

Because of this, his last trip back, with his father to his childhood, would have resulted in the same issue with both his existing children. They would have been changed. It simply doesn't make any sense.

If, on the other hand, we accept it was ok for him to go back to his boyhood, because the episode was so isolated that it wouldn't change anything later, it totally takes away the threat attached to visiting his father after his father's death/birth of a later child, because he could simply go back to one of the many times his father was locked away reading and would have no influence on the future. He could visit his father as often as he liked.

I admit there is an element of breaking a butterfly on the wheel here, worrying about this level of detail, but fantasy should work within the confines of its own rules. Once it starts breaking those rules, it doesn't even work as fantasy any more, it is just a mess.

Published on October 07, 2013 00:37

October 4, 2013

Death of a colony

It's fashionable to criticize friendships made online as second rate, but as my friend Henry Gee (met via Nature Network) has pointed out, in reality it often leads to 'real world' events and encounters that make it every bit as rich as going down the pub. Personally I have only ever been members of three online communities - Nature Network, a blogging/social network set up by the journal Nature; BWBD, a forum for bloggers with book deals; and Litopia. As it happens all three are now defunct or nearly so, but the one I particularly wanted to mourn here is Litopia.

It's fashionable to criticize friendships made online as second rate, but as my friend Henry Gee (met via Nature Network) has pointed out, in reality it often leads to 'real world' events and encounters that make it every bit as rich as going down the pub. Personally I have only ever been members of three online communities - Nature Network, a blogging/social network set up by the journal Nature; BWBD, a forum for bloggers with book deals; and Litopia. As it happens all three are now defunct or nearly so, but the one I particularly wanted to mourn here is Litopia.Litopia was by far the biggest of the three and was set up by my former agent, Peter Cox, as a kind of extension of his agency, but interfacing to the world through an open (and very large) forum for writers published and hopeful to get together, compare notes and generally support each other. As such, for several years it worked very well, and there are a range of writerly people around the world I now count as friends who I would not have met without it.

Unfortunately Litopia suffered from regular upheavals, some due to personality clashes with large egos involved, some due to misuse of the environment or to over-heavy moderation. In the end, there was an almighty row and it was 'temporarily' taken down. In a sense it was inevitable, as Peter, who largely funded the whole enterprise from his own pocket, had a different idea of what Litopia was for than most of those involved.

This take-down happened some while ago, but I am only commenting on it now because it seems clear that this temporary suspension has become permanent. Litopia isn't coming back. The good news for Litopians who miss their online friends is that there are ways to get together online still and many of the old faces regularly do - but I still think the passing of this worldwide meeting place is sad, a bit like an often-used pub closing down, and as such it is important to mark its passing.

A lot of people got a lot out of Litopia - for me it was mostly the social aspect, as writing can be an isolated business where you don't meet others doing the same job. For others it was a major boost to their writing, with free (if sometimes ferocious) criticism available of their works in progress. So farewell, Litopia. You started a lot of good things.

I ought to point out that Litopia's sister, Radio Litopia, a collection of podcasts and web-based broadcasts on writing and the wider communication world is still up and running and can be found here.

Published on October 04, 2013 00:57

October 3, 2013

Ebooks and skip-reading

Said ebook opening.

Said ebook opening.(Is it just me or is there no way to have

the cover full screen in iBooks?)The other day I was stuck somewhere with nothing much to do. I had finished the book I had with me, but I had my iPad about my person, so I fired it up and opened a book I had downloaded some while ago in Starbucks' nice little Apple collaboration where they have those weekly little cards that allow you to get a free book, tune, TV programme or app.

It proved sufficiently engrossing that I read about 1/3 of it on my train journey from Cardiff to Swindon. But it did make me wonder if ebooks and page turners were a dubious combination. The thing is, I tend to skip-read fiction at the best of times. I will slither my eyes across a descriptive passage, getting a general feel without bothering with the detailed words. I'm sure it's very sad for authors who have spent hours crafting that beautifully drawn setting, but I just want to get on to something happening.

What I found with this book was that I was doing it more than usual. I was getting through an iPad page in just a few seconds before flicking onto the next. In that time I was getting all the dialogue, all the essential plot details and a feel for the descriptive bits. It was quite addictive, flicking forward, soaring through it. It really did seem that the combination of relatively short pages and the ability to so easily flick on encouraged this naughty way of reading.

Now this wasn't great literature, it was a popularish title and an easy read. But my suspicion is that whatever I read on the iPad I will read less thoroughly than I would if it were a paper book. I haven't noticed it before as this was the most extreme example, but on thinking about it, I suspect it is true. And I don't know if I should be sad that the growth of ebooks means that more of us are likely to be reading books in this rather summary fashion more frequently.

On the other hand, it would mean I could read some of the more poseurish literary novels in about 10 minutes, as I would constantly be flicking and never hitting any substance. So perhaps it isn't so bad after all...

Published on October 03, 2013 00:01

October 2, 2013

The Late Pig and the Daily Mail

Whatever your politics, it's hard not to feel sympathy for Ed Milliband when the Daily Mail makes such a scathing attack on his late father, and if the Mail intended this to turn people off Labour, I suspect it has backfired in quite a big way.

Whatever your politics, it's hard not to feel sympathy for Ed Milliband when the Daily Mail makes such a scathing attack on his late father, and if the Mail intended this to turn people off Labour, I suspect it has backfired in quite a big way.Part of the problem with any such headline-based spat is that we get immediate knee-jerk reactions to 'the man who hated Britain' and yet actually the picture is much more nuanced, something that has struck me while reading a book by one of my favourite authors, Margery Allingham.

Let's be clear - I do not agree in any way with the late Ralph Milliband's politics. I think Marxism is a dire system that more than throws the baby away with the bathwater. It is ill thought out and destructive. But popular British books from Milliband senior's formative period really do demonstrate that there were things to hate about Britain back then. I've commented before on the casual racism in Dennis Wheatley's books. We may still have some problems with race, but the British attitude back then, which considered even as close and kindred a nation as the Irish to be sub-human, was well deserving of hatred. And in the Allingham book I'm reading at the moment, another aspect we've pretty much forgotten now rears its very ugly head.

The book in question is The Case of the Late Pig. It should be classic Allingham, written in the 1930s, but in fact it is one of her weaker books about Albert Campion, in part because she chooses to write it in the first person with Campion narrating, which means we lose the wonderful contrast between his apparent foolishness and actual cleverness. But another problem for me is a truly hateable concept at the core of the story.

A major player in the book is the local Chief Constable, very local by modern standards, dealing with a tiny police force. Campion treats this man with a huge amount of respect and deference, despite the fact that he is clearly a complete idiot and incompetent. What we forget about Britain in the 1930s, and I'm sure one of the things that Ralph Milliband hated, was that we were expected to defer to such people simply because of their status and class. It didn't matter how awful they were at their job, Allingham makes it clear that this bumbling ineptitude should be treated with affection, because the Chief Constable (an ex-army officer, of course) was the right kind of person. Thankfully this attitude has entirely disappeared, with the exception of some people's ridiculous attitude to the royal family. But it is a powerful reminder of what the country the young refugee Milliband was brought to was like.

So, yes, let Ed defend his dad, and tell us that he loved Britain. But it's not all black and white. There was plenty not to love that has got a whole lot better since. And we shouldn't forget that.

Published on October 02, 2013 00:25

October 1, 2013

Very good advice from Goodreads

I tend not read reviews of my books on Goodreads or Amazon. Don't get me wrong, it's not that I don't appreciate people writing them - I do. But while I tend to make use of good reviews in the press, for instance quoting them on my website, all reading a Goodreads or Amazon review can do is slightly inflate my ego (if it's good) or make me feel really grumpy (if it's bad).

I tend not read reviews of my books on Goodreads or Amazon. Don't get me wrong, it's not that I don't appreciate people writing them - I do. But while I tend to make use of good reviews in the press, for instance quoting them on my website, all reading a Goodreads or Amazon review can do is slightly inflate my ego (if it's good) or make me feel really grumpy (if it's bad).I was looking at the Goodreads widget, something you can put on your website to point people to Goodreads reviews of your books (which, as I said, I don't want to do, but hey I was curious) and I noticed the top review shown for my book A Brief History of Infinity was a 2 star one that started off pretty damned miserably.

I couldn't help but be sucked in and looked at the rest (which, true to form, made me feel grumpy). But I was then cheered up by some superb advice from Goodreads at the bottom, discouraging authors from responding to a bad review. They are so right. It is tempting, and I know some people who have succumbed and done it - and they all regretted it. I would certainly never do it. I once had a review removed from Amazon because it was a downright lie and irrelevant to the book it was supposedly reviewing - and Amazon took it down straight away. But even that probably wasn't worthwhile, as the same person then put up another negative review, this time also crying foul because his last one had been taken down.

It's fascinating because this is totally different to the advice of what to do if a customer complains about your service as a business. In that case it is best to respond (and generously at that), because if you recover the situation you win a strong supporter. But bear in mind the crucial difference. When customer service goes wrong we are talking about something that can be fixed. But when someone gives you a bad review we are simply dealing with someone whose doesn't like what you've written. You won't win them over by arguing - or by sending them a present. They still won't like your book. So grin and bear it. If you find that impossible to do, don't look at these reviews. Your blood pressure will thank you.

It is worth repeating Goodreads' wise words below:

Ok, you got a bad review. Deep breath. It happens to every author eventually. Keep in mind that one negative review will not impact your book’s sales. In fact, studies have shown that negative reviews can actually help book sales, as they legitimize the positive reviews on your book’s page.

We really, really (really!) don’t think you should comment on this review, even to thank the reviewer. If you think this review is against our Review Guidelines, please flag it to bring it to our attention. Keep in mind that if this is a review of the book, even one including factual errors, we generally will not remove it

For more on how to interact with readers, please see our Author Guidelines.

If you still feel you must leave a comment, click “Accept and Continue” below to proceed (but again, we don’t recommend it).

Published on October 01, 2013 00:24

September 30, 2013

Valobox: seeing books differently?

History is littered with startup websites that intended to break the mould. A few did. Many more were themselves broken by the market. Because what seems a good idea in your garage doesn't necessarily make a lot of sense when it becomes available to the world.

History is littered with startup websites that intended to break the mould. A few did. Many more were themselves broken by the market. Because what seems a good idea in your garage doesn't necessarily make a lot of sense when it becomes available to the world.I am honestly undecided about one such new website in the publishing field, Valobox. It is, they say, a new way of accessing ebooks. The idea is that you can take a look at an ebook online, read a chapter free and then either buy the whole book or individual chapters at a time. It is all done in the browser, so there are no apps and it works on anything that can run a browser.

It's a really fine balance when you put it up against something like Kindle. Using the Amazon ebook format gives you a free sample chapter, and is readable on pretty well any platform you can think of. Here's my quick pros and cons for Valobox:

PROS

It's simple and you can try before you buyIt has text searching, highlighting etc.Works anywhere without downloading an appUnique ability to buy selected chapters (could be useful in non-fiction and/or research)

CONSAlthough the formatting on web pages is good, it's not as flexible as an appYou have to have internet access - can't download and read offlinePage turning is quite slow as you have to wait for download (though a whole chapter comes as a single page)I really can't make up my mind what I think about Valobox. I suspect in the end, the convenience of using Kindle or iBooks, with their vast libraries and easy apps, will probably generally push me in their direction. And I do like to be able to read offline. But I will be disappointed if Valobox fails as it is a very neat concept. Why not give it a try?

To get a feel for it, here is the Valobox version of my book Roger Bacon. You can see exactly what is available for free and what you would pay for the rest, though if you join (it's free and you get $1 credited to your account) you can select another 10 pages to read for nothing.

Published on September 30, 2013 00:07

September 27, 2013

The day a comet came to tea

I found myself yesterday at the Royal Institution in London. The poor old RI has struggled to find its place over the last few years. It's understandable. With my heart I love this old pile and all it's historical baggage. I mean, this was where Faraday went from being a bookbinder's apprentice to one of the greatest physicists ever. He, of course, began the wonderful Christmas lectures for children that inspired so many would-be scientists, including me.

I found myself yesterday at the Royal Institution in London. The poor old RI has struggled to find its place over the last few years. It's understandable. With my heart I love this old pile and all it's historical baggage. I mean, this was where Faraday went from being a bookbinder's apprentice to one of the greatest physicists ever. He, of course, began the wonderful Christmas lectures for children that inspired so many would-be scientists, including me.With my head, though, it is ludicrous that an establishment like this should be positioned in such a ritzy bit of real estate, in what must be amongst the most expensive districts of London. Think how much more outreach the RI could do if it sold up and bought a more flexible and accessible site. And yet...

One of the best things the RI used to do is to have regular events where the author of a new popular science book would talk about the subject. It's where I got my first chance to speak there, when A Brief History of Infinity came out. These events seemed to win all round - the punters got an interesting talk (mine was sold out), and the RI got a subsidy as the publisher would contribute financially/arrange drinks for the audience afterwards in exchange for being able to sell copies of the book. These events were stopped by the previous administration, which was a real shame.

However the new RI seems more open to different kinds of events, and yesterday I spoke at the launch of a book (currently in the form of an iPad app) for young children called The Day A Comet Came To Tea . It was a fun event in one of the RI's smaller rooms, but I have to say it worked particularly well because of the atmosphere. So maybe the heart ought to win, maybe it is worth keeping that wonderful old building.

As for the comet book, it's a great example of how you can introduce a touch of science into even the youngest children's books. It is story book - it doesn't attempt to heavy handedly educate (which is always a disaster in fiction), but it does give a hook to then talk about some interesting science, always the most important thing in getting children started.

I know the RI is in financial difficulties, but I think if it could do more with publishers again - physical and digital - in the future it would help both make its programme more inspiring and to keep it going in a rapidly changing world.

Published on September 27, 2013 00:38

September 26, 2013

Hating a word

The other day I was watching that ever popular soap opera Coronation Street (come on, I'm a Northerner. It's an old charter or something - I have to watch it or I will be expelled from the South). A couple of times in the episode, characters used a word that totally sets my teeth on edge. I hate it with a vengeance.

The other day I was watching that ever popular soap opera Coronation Street (come on, I'm a Northerner. It's an old charter or something - I have to watch it or I will be expelled from the South). A couple of times in the episode, characters used a word that totally sets my teeth on edge. I hate it with a vengeance.That word is 'scran', meaning food, but in a 'shovel it in, don't care what it is,' sense. Now you might think that my delicate sensibilities are being offended by this being a relatively new word, and slang to boot. But no, I might not like every neologism, but I coexist quite happily with most of them. I can even cope with LOL being used verbally, as one of my daughters sometimes does. And anyway, scran isn't new.

The OED has references for it being used for food going back to 1808, though interestingly then it was rubbishy food - to be precise 'broken victuals'. The oldest quote is worth repeating, as it is very fine:

Fine skran, a phrase used by young people when they meet with any thing, especially what is edible, which they consider as a valuable acquisition, S. 2. The offals or refuse of human food, thrown to dogs, Loth.Later, it apparently entered nautical slang as a more general term for food. So, really, here is a word with a fine pedigree. But it simply winds me up to the extreme.

Answers on a postcard as to why. I really don't know.

Published on September 26, 2013 00:02

September 25, 2013

Its the usage, stupid

A rather young me as BA's PCHQ Manager.

A rather young me as BA's PCHQ Manager.Shame about the hair.When I worked at British Airways, one of my main interests was user interface design and it has remained a passion for me ever since. If there's a 'first rule of user interfaces' it is not that we don't talk about user interfaces. Rather it is that the user interface should not get in the way of what you are trying to do. All too often it does, and I've had a good example of this recently.

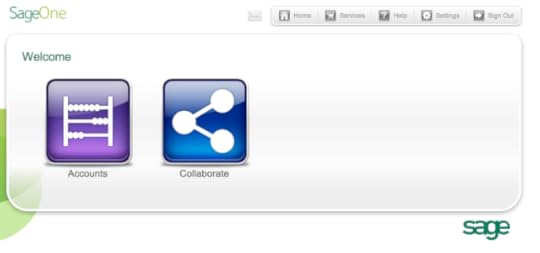

I do my accounting use an excellent online package called Sage One . It is easy to use, makes doing my VAT returns and accounts a breeze and generally keeps me on top of my business finances. And being online, I can access it from any device, wherever I like. So far, so good. And up til now, when I logged in I went straight to my main account screen. Now, though, when I log in I get the screen below.

I then have to click on the Accounts button and I'm where I started before. It's just one extra screen, yet it is enough to be irritating. They have added in an extra feature where I can collaborate on my accounts with my accountant. This is fine, but I don't currently use it, and if I did, I would probably only do so once or twice a year. So they have made me go through an additional screen, almost always using exactly the same selection. I am inconvenienced maybe two or three times a day for something I will only use annually.

What they should have done is continued to go straight into the accounts screen and given an option, for instance in that menu at the top, to go to another module like Collaborate. (In fact I think this may even be what the 'Services' option does.) But instead, they have messed up their interface.

What they should have done is continued to go straight into the accounts screen and given an option, for instance in that menu at the top, to go to another module like Collaborate. (In fact I think this may even be what the 'Services' option does.) But instead, they have messed up their interface.I have pointed this out to them and they are considering whether or not to make a change. I hope they see sense. After all, my user interface consulting is usually charged out at a considerable rate...

Published on September 25, 2013 00:26