Brian Clegg's Blog, page 106

December 13, 2013

A pun-ishing yet pleasant read

There is a long tradition of humorous fantasy that has followed two broadly diverging paths - a more sophisticated route in the UK (typified by Terry Pratchett and Douglas Adams, whose writing, though apparently science fiction could probably be more accurately classed as fantasy) and a rather less subtle approach in the US.

There is a long tradition of humorous fantasy that has followed two broadly diverging paths - a more sophisticated route in the UK (typified by Terry Pratchett and Douglas Adams, whose writing, though apparently science fiction could probably be more accurately classed as fantasy) and a rather less subtle approach in the US.This American genre varies from the hugely entertaining Amber stories of Roger Zelazny (which are primarily adventures, but maintain the wry humour of a noir detective story) to downright silly but fun romps like Bring Me the Head of Prince Charming (also by Zelazny). But I had not realized quite how far these books could go in intensity of groan production until coming across Board Stiff.

The book was written by Piers Anthony, a long standing member of the SF and fantasy community who may never have been quite in the first rank, but has turned out many readable tales over the years. It was, I admit, with some trepidation that I approached the book when it was offered to me as it is number 38 (no, not a typo) in the Xanth series of novels. It really is hard to imagine someone reaching that number without churning them out (with the exception of Pratchett), but I was willing to give it a go, having been assured that no previous knowledge of Xanth was required.

Overall the experience was surprisingly pleasant. What we have here is a classic quest story, with a likable cast of characters and some impressive tasks to achieve and obstacles to be overcome. I particularly liked the character Astrid, a basilisk in human form, struggling with the conflict of wanting to taste humanity while being deadly to the species. But there is a price to payment which is coping with the numerous puns that litter the book. Practically everything we meet is a pun of some sort, from the strong drink boot rear, to the central character Irrelevant Kandy, who is either ignored if known by her full name, or lusted after if known as I Kandy. Even the central arc of the story concerns puns and their importance to Xanth.

Kandy's name also brings out the other slightly cringe-making aspect of the series, which is a 1950s-esque coyness about sex, which has been codified into a complex running joke. (Babies, for instance, really are brought by the stork, and the sight of a girl's panties causes any man to freeze in his tracks and remain comatose until snapped out of it.) Combined with a very simplistic writing style this will put a fair number of readers off, though I found it tolerable as long as the book is read with the same sort of 'dated approach' mental filter you have to apply now when reading, say, Asimov's Foundation series.

Overall, an enjoyable, lightweight way to spend a few hours. Unless you are true pun-head it is unlikely to give more than passing amusement, but it is, in the manner of the Earth in Hitchiker's Guide to the Galaxy, mostly harmless.

Board Stiff is available from 6 January 2014 and can be pre-ordered before then on Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com.

Published on December 13, 2013 03:26

December 12, 2013

A Question of God

I am delighted to welcome J. S. Watts as my latest guest blogger. J.S.Watts is a UK writer. She has written three books: two of poetry, “Cats and Other Myths” and the multi-award nominated “Songs of Steelyard Sue” (published by Lapwing Publications) and a novel, “A Darker Moon” (published by Vagabondage Press). She has had a long term interest in mental health issues because of family issues and her work in education. She has served on various Mental Health Act panels and been a Mental Health Trust governor. See her website for further details.

I am delighted to welcome J. S. Watts as my latest guest blogger. J.S.Watts is a UK writer. She has written three books: two of poetry, “Cats and Other Myths” and the multi-award nominated “Songs of Steelyard Sue” (published by Lapwing Publications) and a novel, “A Darker Moon” (published by Vagabondage Press). She has had a long term interest in mental health issues because of family issues and her work in education. She has served on various Mental Health Act panels and been a Mental Health Trust governor. See her website for further details.GUEST POST

I’m actually a little hesitant about writing this guest post. I mean, what’s a poet and fiction writer doing writing for a science based blog? Do I have the scientific chops for this? Also, by choosing to share some thoughts on the tricky subject of religious delusion in the seriously mentally ill, I know I could be treading on thin ice and who knows what lies beneath?

Let me be upfront about a few things. I’m not a clinician, scientist or mental health professional. I’m just a writer who observes things, particularly people, and likes to know what makes them tick. I’m also someone who likes to ask questions – lots of questions. One of my earliest spoken phrases was, apparently, “wasat?”, closely followed by, “why?”. This post is just me pondering and asking questions about what I’ve observed during a close association with the UK’s mental health services through family connections, past professional work in the education sector and voluntary work I’ve chosen to undertake.

My principal question is why does religion seem to feature so significantly in the delusions of people with serious mental health problems? I’ve met people who believe they are God (Judaic/Christian/Islamic variety), a god (South American in this context, but other pantheons would probably serve as well), talk to God and angels, hear demons, have found the answer to eternal life and are being confounded by the Anti-Christ (me, on that occasion). What is it with religion that it finds its way into people’s psychoses on such a regular basis?

Is there a historical link? Once upon a time, people who heard voices might be lucky enough to be acclaimed seers, saints or prophets (unless they were unlucky enough to be deemed witches or possessed). These days, hearing voices is likely to earn you the label of schizophrenic or psychotic. Does the knowledge of past, positive, cultural interpretations of internally heard voices play to our need for illusory superiority and colour our experiences today?

Are we looking at a social phenomenon? For years humanists such as Julian Huxley have seen religion as a prop or crutch some people are born needing. On the other side of the argument, the Christian Church offers itself up as a refuge and shelter for those in need. In the despair and chaos that can be experienced during extreme mental ill health, is it surprising that religion becomes involved in chaotic mental processes, both as a potential source of salvation and as evidence that life is truly hellish?

Does religious delusion have a physiological cause, running deep in our DNA and hard-wired into our brains? Here, I’m thinking of geneticist Gene Hamer whose hypothesis proposes that a specific identifiable gene predisposes humans towards spiritual or mystic experiences. Whilst this theory has had its gainsayers, more recent psychological research by Professor Bruce Hood suggests that magical and supernatural beliefs are hardwired into our brains from birth, whilst yet other researchers have found evidence linking religious feelings and experience to particular regions of the brain which can be stimulated to induce feelings of religious euphoria or the sense of a divine presence. Mental illness often has physiological roots and can be caused by the brain’s chemistry malfunctioning, so perhaps the repeated God delusion is just a sign of our mental wiring playing up?

Despite clinical advances in the diagnosis and treatment of mental illness and the phenomenal work of some truly committed and outstanding people, my own observations and the sea of fluctuating and misdiagnoses I have come across, lead me to believe that psychiatry today remains, in many cases, as much an art as a science. For this reason, I am sure, it has proved a source of endless fascination for creative writers from Charlotte Bronte to Sebastian Faulks, with his epic “Human Traces” and the fictionally more successful “Engleby”. Less exalted writers such as myself have also grazed the subject matter. In my dark fiction novel, “A Darker Moon”, one man’s search for himself has both psychological and mythic roots. Like this blog post, the novel raises questions about life, sanity and being human - which it does not claim to answer. The solution to what is delusion and what is true is not a clear one. Indeed, one reviewer who praised the book commented “Each of us will see some form of light at the end of this author's tunnel, but it won't be the same one, the same colour, or even the same destination.” and isn’t that a bit like life itself?

Despite clinical advances in the diagnosis and treatment of mental illness and the phenomenal work of some truly committed and outstanding people, my own observations and the sea of fluctuating and misdiagnoses I have come across, lead me to believe that psychiatry today remains, in many cases, as much an art as a science. For this reason, I am sure, it has proved a source of endless fascination for creative writers from Charlotte Bronte to Sebastian Faulks, with his epic “Human Traces” and the fictionally more successful “Engleby”. Less exalted writers such as myself have also grazed the subject matter. In my dark fiction novel, “A Darker Moon”, one man’s search for himself has both psychological and mythic roots. Like this blog post, the novel raises questions about life, sanity and being human - which it does not claim to answer. The solution to what is delusion and what is true is not a clear one. Indeed, one reviewer who praised the book commented “Each of us will see some form of light at the end of this author's tunnel, but it won't be the same one, the same colour, or even the same destination.” and isn’t that a bit like life itself?Indeed, I’d go so far as to suggest that this fundamental ambiguity may also have something to do with the frequency of religious delusions in psychotic episodes. In saying this, I do realise that some people are so ill that the implausibility of believing themselves to be the US President or their wife a hat is immaterial, but for those whose psychosis co-exists with the real world, how can they or their medical advisors prove that they are not God or that the voices they hear are not demonic? You can believe it to be nonsensical and a sign of mental illness, but can you actually prove it? Really? It may be worth remembering that one man’s strong religious belief is another’s ill-advised superstition, can be another’s evidence of mental illness. Surely past historical acceptance of people hearing voices and experiencing divine revelations, when compared with the Roman Catholic Church’s current day belief in miracles and the beatification of modern saints, teaches us that there is still a spectrum of perceptions ranging from religious experience to mental illusion. Boundaries between the two are not as clear cut in the 21st Century as those of us who emphasise the scientific and rational in life would like to believe.

Oh look, there’s that word again, “belief”: a concept that has been central to human existence for millennia, may be hardwired into our brains and our DNA, has extensive social, cultural and historical roots and for many people is as ambiguous as an imprecise psychiatric diagnosis. Even when allegedly well, we argue over it, fight over it and kill for it. Maybe it’s not that surprising, therefore, that such an integral part of the human condition is with us in illness as well as health?

Published on December 12, 2013 01:54

December 11, 2013

Family history looming large

Image reproduced with the permission

Image reproduced with the permissionof the Whitaker Museum and GalleryI have recently had this painting brought to my attention and I couldn't help be fascinated. It's called 'girl at a Preston loom' and it was painted by one William Clegg in 1869. I've no idea if William was a relation - Clegg is a fairly common name in Lancashire - but I can't help be drawn to the image.

Apart from anything else, it was unusual for painters then to represent such lowly figures, so it's a rare example of a painting of what was then a common sight.

But apart from the coincidence of name, it also grabs my attention because my grandmother started work in a cotton mill at an early age and my suspicion is that, though the machines were probably rather larger in Annie Pickersgill's day, the technology was likely to be very similar.

To my shame I can't remember exactly when Annie started work - I know that she began to attend the mill for half days before she left school to get used to it, and I've a feeling that started when she was around age 11 (which would be in 1910). She was certainly no older.

Although I certainly heard tales of camaraderie from my grandma, the mills were not a pleasant place to work. The noise from the machines was intense - communication on the mill floor was largely by sign language - and early deafness was common. If looking at that painting makes you wonder if it was a good idea to be stood in full skirts in such close proximity to whirling, unprotected gear wheels (remember this, next time you moan about health and safety gone mad), you might be inclined to think that the painter was using some artistic licence, but I certainly heard plenty of tales of clothes (and hair) getting caught in the machines, sometimes with dire consequences.

I'm not the kind of person who has a rose-tinted nostalgia for the 'olden days'. It was a horrible way to work, though we probably had to go through it as a nation to haul ourselves out of the earlier rural squalor that most lived in. But equally it's not a time or a way of life we should forget, and I think we should celebrate people like Annie Clegg (as Miss Pickersgill later became) and their work.

The painting is now at the Whitaker Museum and Gallery in Rossendale, though I believe it is currently in store rather than on display.

Published on December 11, 2013 00:28

December 10, 2013

Shadows Beyond

It seems particularly appropriate with Christmas on the way, when a lot of us have a bit more time to dip into fiction, to be reviewing a young adult fantasy novel in ebook form that would appeal to adult readers as well.

It seems particularly appropriate with Christmas on the way, when a lot of us have a bit more time to dip into fiction, to be reviewing a young adult fantasy novel in ebook form that would appeal to adult readers as well.Val Tyler's Shadows Beyond takes us into a world where the teenage Emtani must travel from the only life she has known in a small village to the unknown of the city, where her young sister has been taken as a slave. With grotesque crime lords, a glossy upper city with a horrible secret and a dark underbelly where the Luciphorous Factory leaves slave workers horribly disfigured, it has the feel of a dystopia, but without the total absence of hope that tends to make dystopias ultimately too depressing to be an enjoyable read. Despite all the trials and horrors Emtani and her friends go through, there is a positive side to their experience too.

In some ways this isn't a book I would naturally be attracted to. The fantasy element involving headlets and shadows (you will have to read it to find out what this entails) was difficult to accept alongside the laws of physics. (I know fantasy, by definition, involves things that are inexplicable, but I like to feel that there could be an explanation that we just don't have yet.) However, the author's storytelling skills soon had me swept away, and once I was a couple of chapters in I was hooked and wanting to know how things turned out.

With some clever twists and a relentless, driving action throughout it is a book you will resent having to put down.

See at Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com.

Published on December 10, 2013 03:03

December 9, 2013

What colour is an electron?

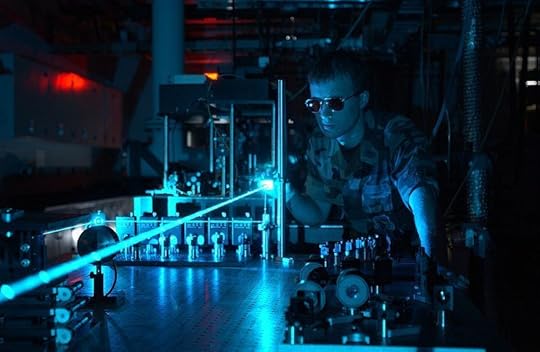

What colour is a beam of blue light?Not long ago I facetiously commented on Facebook that electrons were pink. The next day, an X-ray crystallographer asked me 'As someone with a physics background, what colour would you say an electron is?' I almost fell off my chair. But once I started to think about it, it's a really interesting question - and one that might be worth first approaching by asking another apparently silly question.

What colour is a beam of blue light?Not long ago I facetiously commented on Facebook that electrons were pink. The next day, an X-ray crystallographer asked me 'As someone with a physics background, what colour would you say an electron is?' I almost fell off my chair. But once I started to think about it, it's a really interesting question - and one that might be worth first approaching by asking another apparently silly question.What colour is a beam of blue light? The answer certainly doesn't have to be blue. Before I explain why, let's put relativity out of bounds. Once you start moving, colours are moveable feasts - think blue/red shift. But I'm envisaging a much simpler situation. I show you a beam of blue light and ask you what colour it is. I can guarantee you would not answer 'blue'.

To avoid distraction, what I will do is shine the blue light down a cylinder with a black interior, turn the lights off in the room and open a door on the side of the cylinder so you can see the light passing through. What would you see? Nothing. Because in one sense you can't see light. Obviously this sounds bonkers. Light is all we do see. But the point is that when we see that we see light we mean something totally different to seeing, say, a postbox. When I say I see a postbox, what I mean is that the light from, say, the sun, hits the postbox, is re-emitted by the box towards my eyes, and I see the box. So 'seeing' usually means detecting the light that hits an object and comes back towards us. This just doesn't happen with light. Light passes right through a beam of light - it doesn't reflect off it. So we don't see a light beam sideways on.

You may at this point be thinking, 'but what about laser beams and spotlight beams and such? You see those sideways on.' And as the picture above demonstrates, you do. But only because the beam is hitting something in its path - dust, water vapour or smoke, for instance - and some of the photons are being scattered off their path towards your eyes. Otherwise there would be nothing to see.

So bearing this in mind, let's go back to 'What colour is an electron?' My initial thought in response to the crystallographer was that it doesn't have a colour as you could either consider it a dimensionless point or a spread out, fuzzy quantum collection of probabilities, and in both cases the concept of colour is meaningless. But he had something different in mind.

He said that physicists usually think of electrons as blue (perhaps as a result of the Čerenkov radiation given off by electrons in nuclear power plants), and tend to think of positively charged things as red, which is the opposite of the convention he used. He was just talking about arbitrary conventions. But now that I come back to the concept given the insight from 'What colour is a beam of blue light?' I think that maybe there is a real answer.

When we see a postbox as red, what is happening is that the box is absorbing photons from the sun with a range of energies corresponding to the whole visual spectrum (and beyond). Much of the energy from the photons simply goes into increasing the energy of the atoms in the box (effectively warming it up a little), but some of the energy is re-emitted as photons, preferentially in the red range, so we see the box as red. 'What colour is a postbox?' really means 'What energy range of photons are re-emitted by the box?'

Specifically, the particles responsible for that re-emitting are electrons. When light hits an object, the electrons around the atoms in the object absorb the light energy, jumping up one or more levels. The light that comes back off the object, enabling us to see it, is the result of those electrons dropping back down in energy, releasing a new photon or photons. So arguably the colour of the electron is the colour of the light it re-emits. This varies depending on the electron's state - so you could argue that the real answer to 'What colour is an electron?' is not 'It doesn't have a colour,' but rather 'An electron is a bit like a chameleon. It has different colours depending on the state and situation it is in.'

There's nothing like a silly question to get the brain in action.

Image from Wikipedia

Published on December 09, 2013 01:18

December 6, 2013

Thinking on your feet when the ground is rolling under them

Here's another guest post from Richard Sutton, who introduces himself: From San Rafael, California on a windy January in 1952, it's been a wild ride. My folks never settled down until long after I'd moved to a cabin I built on a commune in Oregon, but I couldn't sit still -- the wanderlust was in my blood. After college, I hitchhiked to New York City in 1973. There I met my wife on Canal Street and finally found a home.

I learned my first craft post-college, spending 20-plus years in the trenches of NYC advertising and publicity as a graphic designer, marker-pen-jockey, art director and copy writer. I served the needs of a wide range of clients from corporate multinationals to non-profits and small retail businesses. I now limit my design and marketing work to book covers and collateral marketing for authors. Somewhere in there I began writing fiction and short stories and began trading in authentic American Indian arts. My first novel, The Red Gate, was released in 2009 and three more have followed. The most recent, Troll, is a fictional look at the origins of racism and fear of outsiders in a pre-historic setting.

GUEST POST

A number of years past, I was struggling to design a web presence for our family business. It was 1995, and despite my more than twenty years of commercial communications design cred, it was eluding me. Each time I’d lay the elements upon the new page, something would draw my attention and once I returned, it resembled a heap of blocks after a child’s tantrum. Images, blocks of text, graphs and charts, lying in an uncertain, unrestrained heap at the bottom of a seemingly endless page.

A number of years past, I was struggling to design a web presence for our family business. It was 1995, and despite my more than twenty years of commercial communications design cred, it was eluding me. Each time I’d lay the elements upon the new page, something would draw my attention and once I returned, it resembled a heap of blocks after a child’s tantrum. Images, blocks of text, graphs and charts, lying in an uncertain, unrestrained heap at the bottom of a seemingly endless page.

I browsed hundreds of sites. Many were rough piles, just like my work. The few with order and sense, were composed mostly of images with little information. I would click away on each image, but none were linked to anything, so I wondered what the point was. Possibly, it was the frustration of these displays of color and form with no underlying meaning that led me to a realization.

Like all designers whose work occurred upon some form of printed page, the only thing we knew was producing communications to be seen in two dimensions. Flat. Linear. Page-wise. These static examples viewed on a screen were an attempt to utilize the existing, rudimentary tools in the html codes, to create sophisticated displays in a new environment. They were two-dimensional thinking stuck in cyber space. Nothing I had learned up to this point prepared me to think in more than two dimensions at once when designing communications tools such as advertising, etc. I had grown up in the universe of magazines, newspapers and books. Package design, even when properly die-cut and assembled, was still created in two dimensional thought space. Up until then, a message would be found, essentially in one place. Digested and absorbed in the same place it was conveyed. A single meal. One-stop.

The world-wide-web (as we thought of it then) required a new way of thinking about presenting information. A technology – print – that had served admirably for hundreds of years, was being eclipsed by something still evolving. It was hard to get a grip on its expanding form, let alone the language that described how it worked.

I slowly learned to use basic html coding, which seemed to reinvent itself every few months. Thus, my good old tool-kit, which contained the most modern forms of really archaic devices, was no longer of value. Messages were now evolving, adapting things. One-stop was no longer enough. It was more about how long you could hold someone’s attention while introducing new concepts tied into the original message, even if it took them outside and off your point of origin. Effective web communications needed to go somewhere and bring the reader along with it. Designers had multiple dimensions to consider, now: multiple venues at once. Showtime took on a completely new and terrifying meaning as it wasn’t just your own lines or even your own set that could trip you up.

The parameters of what could be done online changed as fast as new technology was introduced. Keeping current became impossible for me, so I learned to stay conversational with the last “current edge”.

Which is where I have remained. I turned away from implementing the newest bells and whistles in my work, to sticking with the primary goals and messages to reach the market segment. One thing I’ve learned to do which before seemed counter-productive, is to view competitors and other connected interest sites as where the edge of my own sites lie. A message I might want to share now has a really wide, tall, deep range of places it can connect with and be reinforced with.

Oddly enough though, the market is not keeping up with the expansion of the message. No. Now, because of the way visit and selection data is fed into huge databases, the most effective marketing is to the narrowest possible slice of market. I’ve learned – and it hasn’t been easy – that I don’t want everyone to see my message at all. No, I only want to make contact with those niches of potential market that are most likely to respond positively. It makes the process so much more meticulous and consigns the “touchy-feely” part of marketing design into little, narrow file folders with very specific titles.

When I began to write fiction for eventual publication, it got even harder to figure out which hat to wear for the job. The marketing of books, especially, has become a much more scientific, data-driven process than it was in the ”Golden Age” of Publishing and Advertising, even as recently as the 1990s. As the means to get a story to its readers have evolved and morphed into a distinctly different process than the publicity plans of the ancients, even the material conveyed has changed. Now a novel, running 450 pages in print on paper, can be delivered to a reader for zero actual cost, beyond the bandwidth needed to transmit the data. No paper, no ink. No warehousing. No shipping. No returns… well few returns.

Today, most marketing efforts for books consist of finding the most receptive slice of market, then making sure that the product is set there in plain sight, as invitingly as possible, including in most cases, sampling before buying as well as interconnected referral networking. Back in the day when I was just getting on my feet as a designer, if you could set up the back page to get them to turn the book over again and open it, you had succeeded. What an amazing change. If you want to remain thinking on your feet now, you’d better grow several additional ones, as two just won’t cut it anymore. I’m learning the dance, but the steps are complicated!

Find out more about Richard's books at his website.

I learned my first craft post-college, spending 20-plus years in the trenches of NYC advertising and publicity as a graphic designer, marker-pen-jockey, art director and copy writer. I served the needs of a wide range of clients from corporate multinationals to non-profits and small retail businesses. I now limit my design and marketing work to book covers and collateral marketing for authors. Somewhere in there I began writing fiction and short stories and began trading in authentic American Indian arts. My first novel, The Red Gate, was released in 2009 and three more have followed. The most recent, Troll, is a fictional look at the origins of racism and fear of outsiders in a pre-historic setting.

GUEST POST

A number of years past, I was struggling to design a web presence for our family business. It was 1995, and despite my more than twenty years of commercial communications design cred, it was eluding me. Each time I’d lay the elements upon the new page, something would draw my attention and once I returned, it resembled a heap of blocks after a child’s tantrum. Images, blocks of text, graphs and charts, lying in an uncertain, unrestrained heap at the bottom of a seemingly endless page.

A number of years past, I was struggling to design a web presence for our family business. It was 1995, and despite my more than twenty years of commercial communications design cred, it was eluding me. Each time I’d lay the elements upon the new page, something would draw my attention and once I returned, it resembled a heap of blocks after a child’s tantrum. Images, blocks of text, graphs and charts, lying in an uncertain, unrestrained heap at the bottom of a seemingly endless page.I browsed hundreds of sites. Many were rough piles, just like my work. The few with order and sense, were composed mostly of images with little information. I would click away on each image, but none were linked to anything, so I wondered what the point was. Possibly, it was the frustration of these displays of color and form with no underlying meaning that led me to a realization.

Like all designers whose work occurred upon some form of printed page, the only thing we knew was producing communications to be seen in two dimensions. Flat. Linear. Page-wise. These static examples viewed on a screen were an attempt to utilize the existing, rudimentary tools in the html codes, to create sophisticated displays in a new environment. They were two-dimensional thinking stuck in cyber space. Nothing I had learned up to this point prepared me to think in more than two dimensions at once when designing communications tools such as advertising, etc. I had grown up in the universe of magazines, newspapers and books. Package design, even when properly die-cut and assembled, was still created in two dimensional thought space. Up until then, a message would be found, essentially in one place. Digested and absorbed in the same place it was conveyed. A single meal. One-stop.

The world-wide-web (as we thought of it then) required a new way of thinking about presenting information. A technology – print – that had served admirably for hundreds of years, was being eclipsed by something still evolving. It was hard to get a grip on its expanding form, let alone the language that described how it worked.

I slowly learned to use basic html coding, which seemed to reinvent itself every few months. Thus, my good old tool-kit, which contained the most modern forms of really archaic devices, was no longer of value. Messages were now evolving, adapting things. One-stop was no longer enough. It was more about how long you could hold someone’s attention while introducing new concepts tied into the original message, even if it took them outside and off your point of origin. Effective web communications needed to go somewhere and bring the reader along with it. Designers had multiple dimensions to consider, now: multiple venues at once. Showtime took on a completely new and terrifying meaning as it wasn’t just your own lines or even your own set that could trip you up.

The parameters of what could be done online changed as fast as new technology was introduced. Keeping current became impossible for me, so I learned to stay conversational with the last “current edge”.

Which is where I have remained. I turned away from implementing the newest bells and whistles in my work, to sticking with the primary goals and messages to reach the market segment. One thing I’ve learned to do which before seemed counter-productive, is to view competitors and other connected interest sites as where the edge of my own sites lie. A message I might want to share now has a really wide, tall, deep range of places it can connect with and be reinforced with.

Oddly enough though, the market is not keeping up with the expansion of the message. No. Now, because of the way visit and selection data is fed into huge databases, the most effective marketing is to the narrowest possible slice of market. I’ve learned – and it hasn’t been easy – that I don’t want everyone to see my message at all. No, I only want to make contact with those niches of potential market that are most likely to respond positively. It makes the process so much more meticulous and consigns the “touchy-feely” part of marketing design into little, narrow file folders with very specific titles.

When I began to write fiction for eventual publication, it got even harder to figure out which hat to wear for the job. The marketing of books, especially, has become a much more scientific, data-driven process than it was in the ”Golden Age” of Publishing and Advertising, even as recently as the 1990s. As the means to get a story to its readers have evolved and morphed into a distinctly different process than the publicity plans of the ancients, even the material conveyed has changed. Now a novel, running 450 pages in print on paper, can be delivered to a reader for zero actual cost, beyond the bandwidth needed to transmit the data. No paper, no ink. No warehousing. No shipping. No returns… well few returns.

Today, most marketing efforts for books consist of finding the most receptive slice of market, then making sure that the product is set there in plain sight, as invitingly as possible, including in most cases, sampling before buying as well as interconnected referral networking. Back in the day when I was just getting on my feet as a designer, if you could set up the back page to get them to turn the book over again and open it, you had succeeded. What an amazing change. If you want to remain thinking on your feet now, you’d better grow several additional ones, as two just won’t cut it anymore. I’m learning the dance, but the steps are complicated!

Find out more about Richard's books at his website.

Published on December 06, 2013 01:11

December 5, 2013

Infinite musings

Infinity, as no end of people keep telling me since I wrote

A Brief History of Infinity

is a big subject, so I like to revisit it now and again. One of the joys of doing my talk on infinity, a real favourite of mine, is the way people's minds are duly boggled by the idea that there can be something bigger than infinity. And what's more, you can prove it without a single equation.

Infinity, as no end of people keep telling me since I wrote

A Brief History of Infinity

is a big subject, so I like to revisit it now and again. One of the joys of doing my talk on infinity, a real favourite of mine, is the way people's minds are duly boggled by the idea that there can be something bigger than infinity. And what's more, you can prove it without a single equation.Thanks to the great German mathematician Georg Cantor we can establish this painlessly. The first step is to discover the concept of cardinality in set theory. A set is just a collection of things, and set theory is the maths that describes the workings of such collections, and from which all the basics of arithmetic can be derived. Cardinality is a measure of the size of the set, and the important thing to be aware of is that if we can pair off items in two sets so they are in one-to-one correspondence, those sets have the same cardinality - they are the same size.

Take a simple example - legs on my dog, Goldie, and the horsemen of the Apocalypse. I can pair of one leg with each of the horsemen. At the end of the process there are no horsemen or legs unpaired. So I can say the legs and the horsemen have the same cardinality. The clever thing about this is I can do it even if I have no idea how many legs or horsemen there are. (I do. It's four. But I don't have to know.)

So let's move on to infinity. The simplest infinite set is just the integers - the counting numbers. Now if I have another infinite set - for instance all the rational fractions - and I can pair off the items in the set with the integers then the two sets have the same cardinality - they are the same 'size' of infinity. And you can do this with the rational fractions. But not all sets of numbers are this accommodating.

Think of the set of every number between 0 and 1. Every single decimal number. This is also an infinite set, but has it the same cardinality as the integers? If I can set up a simple list of the numbers, it has.

So lets imagine that list, going:

0

...

0.5

...

1

and let's imagine writing out the first few numbers. I can't really do this in order, as after zero we will have

0.000000.... all the way to infinity 1

0.000000.... all the way to infinity 2

...

which is rather difficult to write out, so we'll scramble the list and come up with something like this:

0.21584032048303404035930…

0.92939212493373921239446…

0.52030202578403024842231…

0.65873032294825193482488…

0.15740302049304958102733…

0.33335939320293919290111…

Now I'm going to add 1 to the first decimal place of the first number, the second decimal place of the second number and so on all the way through. (If it's 9, I'll change it to 0.) So we go from

0.21584032048303404035930…

0.92939212493373921239446…

0.52030202578403024842231…

0.65873032294825193482488…

0.15740302049304958102733…

0.33335939320293919290111…

to

0.31584032048303404035930…

0.93939212493373921239446…

0.52130202578403024842231…

0.65883032294825193482488…

0.15741302049304958102733…

0.33335039320293919290111…

Now let's pull out those incremented values to see this number:

0.331810...

This is a very interesting number. It's not the first number in the original list, as it differs in the first decimal place. It's not the second number in the list, as it differs in the second decimal place. And so on, all the way through. What we've done here is produce a number that isn't in the list. It actually isn't possible to have a simple list of every number between 0 and 1 - we can't match all the numbers off one-by-one with the integers. The set of numbers between 0 and 1 has a different cardinality to the infinity of the integers - it's bigger.

Enjoy letting your mind boggle at that. This is why infinity is such fun...

Published on December 05, 2013 00:44

December 4, 2013

Carolling merrily

It's that time of year when you can't go into a shop without being pounded with Christmas music, and if you are in a choir you will no doubt be polishing up the Christmas favourites.

It's that time of year when you can't go into a shop without being pounded with Christmas music, and if you are in a choir you will no doubt be polishing up the Christmas favourites.I have heard people moan about Christmas music - and, yes, the shops overdo it - but I have to confess I love it for a few weeks. I shouldn't, being a picky person, because the weird thing is we don't tend to listen to Christmas music at Christmas. Technically speaking it's Advent at the moment and Christmas starts on December 25, lasting for the traditional 12 days. But in reality, Boxing Day (26 December for those of a non-British persuasion) feels about the last day you want to hear Christmas music. I've certainly had enough by then.

Christmas music divides into three chunks, and my favourite is the least well-known. Firstly we've 'Christmas songs'. The ones you mostly hear in the shops. Everything from 'Let it Snow' to 'Jingle Bells' via 'Rudolph, the Red Nosed Reindeer' for the oldies (did you know the reindeer were only added to the mythos as a result of Clement Clarke Moore's 1823 classic poem 'A Visit from St Nicholas', better known as 'The Night Before Christmas'?) and all those Christmas 'greats' the pop world has foisted on us from 'I Wish it Could be Christmas Every Day' (no, you don't, it would be very boring) to 'Stop the Cavalry' (what?) many of which are ridiculous, though I do confess to a special affection for 'Fairytale of New York.'

Second up are traditional Christmas carols. They broadly split between the really traditional ones - a surprising number of which (Including 'In Dulci Jubilo', 'Unto Us is Born a Son', the tune of 'Good King Wenceslas' and the surprise Steeleye Span hit, 'Gaudete!') come from the 1582 Finnish collection Piae Cantiones - and the Victorian standards like 'Once in Royal' and 'Hark the Herald'.

But the type of Christmas music that really hits me in the gut is the modern carols written for choirs to sing. Some of these are miniature musical masterpieces. Some are well know like the 'Carol of the Bells' used in Home Alone, others relatively obscure but beloved by the choirs who find them rewarding hard work: they can be truly gorgeous. Here's a few of my favourites in no particular order that I'd recommend having a listen to:

Bethlehem Down - Peter Warlock (see my earlier post on how this was written to buy beer)Remember O Thou Man - Arthur OldhamAdam Lay Y Bounden - Boris OrdA Spotless Rose - Herbert HowellsThe Oxen - Jonathon Rathbone (ok, probably technically a song rather than a carol, but a cracking setting of the Hardy poem)The Oldham piece, which is my favourite, isn't on YouTube, but here's 'The Oxen' - 2 minutes of sheer gorgeousness. Take a moment from your busy day and have a wallow.

Image from Wikipedia

Published on December 04, 2013 01:30

December 3, 2013

Sceptics need open minds

Like most people with a scientific background it would probably be fair to call me a sceptic, in the sense that I like to see evidence before accepting something. Science and scepticism go hand in hand - think of the Royal Society motto 'nullius in verba' which the Society translates as 'take nobody's word for it.' Or to put it another way, in one of my favourite modern versions, 'data is not the plural of anecdote.' However, all too many sceptics (including some prominent scientists) misunderstand this and turn these into 'without (controlled) evidence this is not true' and 'anecdote has no value' - both of these are incorrect.

Like most people with a scientific background it would probably be fair to call me a sceptic, in the sense that I like to see evidence before accepting something. Science and scepticism go hand in hand - think of the Royal Society motto 'nullius in verba' which the Society translates as 'take nobody's word for it.' Or to put it another way, in one of my favourite modern versions, 'data is not the plural of anecdote.' However, all too many sceptics (including some prominent scientists) misunderstand this and turn these into 'without (controlled) evidence this is not true' and 'anecdote has no value' - both of these are incorrect.What we've got here is a logical error. These people are going from 'without evidence we can't say it's true', which is good scepticism to 'without evidence it is false'. And while it's true that anecdotes have no value in deciding whether or not a hypothesis is true, they are valuable in flagging up the existence of something worth investigating. 'There's no smoke without fire' is obvious tosh, but 'there's no smoke without a cause' isn't.

I bring this up because of a rather sad interview suffered by the excellent paranormal researcher and sceptic, Hayley Stevens. She was attacked in the interview for not simply denying the existence of paranormal phenomena, with the implication that she was leading people astray and that she couldn't be a sceptic if she didn't simply deny and move on.

This is a bit like saying we should deny the existence of UFOs. But of course UFOs exist. We don't know what every object spotted in the sky is, so some of them are by definition unidentified flying objects. This is a perfectly good sceptical view. If we assume UFOs are alien spacecraft, however, that's very different. Then a sceptic should rightly raise a doubting eyebrow. There is no good evidence for alien visitors, and it is extremely unlikely from all we know about the universe and physics. So without such evidence, the starting point has to be that UFOs have perfectly normal terrestrial explanations (or they are weather/astronomical effects). But it is not scepticism to issue a blanket denial that UFOs exist and to criticise those who dare take an interest in them - that is simply stupid.

This is why I felt that it was okay to write my book about the science of the paranormal, Extra Sensory. It is not in any sense a wide-eyed vindication of telepathy or telekinesis. But to simply state that such things don't exist without examining the evidence is just as unscientific as to believe everything you hear from those who have 'witnessed' such events. Scepticism says we certainly shouldn't believe in something without having good evidence - but to take a stand based on not even looking at the evidence is nothing more than superstition.

This is why I felt that it was okay to write my book about the science of the paranormal, Extra Sensory. It is not in any sense a wide-eyed vindication of telepathy or telekinesis. But to simply state that such things don't exist without examining the evidence is just as unscientific as to believe everything you hear from those who have 'witnessed' such events. Scepticism says we certainly shouldn't believe in something without having good evidence - but to take a stand based on not even looking at the evidence is nothing more than superstition.Which is not good science or good scepticism.

Published on December 03, 2013 00:47

December 2, 2013

How a publisher meets his authors

Another guest post by Mark Lloyd. Mark was born in 1972 in the small town of Naas, Co.Kildare in Ireland. He studied at Trinity College Dublin where he was allowed to escape with a BA (Mod) in Computer Science, Linguistics and French.His poetry has been published in Revival Literary Journal, Microphone On! And Boyne Berries. He is a founding member of The Limerick Writers’ Centre, Limerick, Ireland and a member of the Literature Pillar of Limerick City of Culture 2014.

Another guest post by Mark Lloyd. Mark was born in 1972 in the small town of Naas, Co.Kildare in Ireland. He studied at Trinity College Dublin where he was allowed to escape with a BA (Mod) in Computer Science, Linguistics and French.His poetry has been published in Revival Literary Journal, Microphone On! And Boyne Berries. He is a founding member of The Limerick Writers’ Centre, Limerick, Ireland and a member of the Literature Pillar of Limerick City of Culture 2014.He founded Pillar International Publishing in 2012, named after his grandfather’s erstwhile company Pillar Publishing Dublin.

Pillar International Publishing, though focusing on edgy and absurd humour, has also published several poetry collections, including Heartscald by Alphie McCourt and I Live in Michael Hartnett (featuring a piece by the late Seamus Heaney). In humorous fiction and non-fiction, Pillar have published works by Rhys Hughes, Robin Walker and Thaddeus Lovecraft. Pillar, in 2014, will publish works by Tony Philpott and Helena Close, amongst others and will introduce Pillar Vintage, an imprint that will re-issue 1940’s fiction and non-fiction.

GUEST POST

GUEST POSTThere are two books that an author will rarely be told to read but should. Alas they are not published by me.

The Evolution of Cooperation by Robert Axelrod In Praise of Slow by Carl Honoré

The first teaches the importance of proximity and the second the depth of richness offered by time.

Many years ago I ran a small children’s charity that rolled its stone up the hill every morning in its own inimitable style. We received a great deal of funding from one large state body. We received it every year. Not because our mission was that much more compelling than others but because the people who apportioned the money knew that they would meet me every day in the corridor and every lunch-time in the café. We shared a building. They were not aware that this was a deciding factor in their determinations … but it undoubtedly was.

Dragging ourselves forward to the here and now, two of my writers are with me because of very similar reasons. Don’t get me wrong, their writing is marvellous, bordering on spectacular, but they probably would not have been as appealing to me, as interesting to me, had there not been a compelling and regular point in time where our connections would cross.

The first writer I meet online and in person. I holiday in the same small seaside village. We both support Arsenal. The second writer is connected to me through an online community and through Facebook. We both know that in any given day our paths may cross. Compelling reasons to be interested in each other.

Publishing is about personalities, about relationships. If you recognise this, and you act upon it, then you are more likely to succeed.

Go to networking events. Say hello! Join Facebook groups. Say Hi! Attend workshops and festivals. Invest in people. In return, they will invest in you.

Which leads me to my second point. Time. Writing and relationships grow richer with time. Don’t rush it.

For balance, I also think struggling writers should read:

Rum Humour Rum Humor by Thaddeus LovecraftLast Orders at the Changamire Arms by Robin WalkerAnd

The Young Dictator by Rhys Hughes

…because I published them. (See Pillar's website for more on these books.)

Published on December 02, 2013 02:06