Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 45

December 14, 2020

Nest Protect and the nuclear option

I’ve written about Google Nest Protect smoke and CO detectors several times before. The purpose of these posts is to add some helpful tips to the internet, serving as a reference for me and others.

After a year with the devices, I can draw the following conclusions.

They false alarm vastly less frequently than the First Alert system I had owned previously.

With rare exception, when there is an issue, it doesn’t freak out (false alarm) or make inscrutable beeping sounds or blinking lights. It communicates reasonably well through the app or by voice.

But, the devices can become faulty to the point of needing replacement. My 4th (or 5th?) replacement is on the way after a bad experience last night (more below). I own nine devices. This is a high fault rate. Fortunately, Google has replaced them all for free, so far.

When things go wrong, boy do they go wrong! Here’s last night’s story:

Last night around 10PM, the devices were signaling smoke. There was none and the alarm could not be cleared. They also started beep complaining about low batteries. They weren’t low. The batteries last five years and mine were one year old. Moreover, you’re not going to get instantly simultaneous low battery alerts on several devices. That’s a signal of a deeper problem, especially when it’s simultaneous with a nonexistent smoke detection that can’t be cleared. Lastly, they’re not supposed to jump to beeping when they have a low battery. They’re supposed to let you know through the app that you are going to have a low battery issue soon. Quietly!!!.

None of this behavior made sense, and I could not override any of it. After two hours with tech support, during at least an hour of which they kept offering nonsense solutions like battery replacements, we found the problem: a faulty device that set off a cascade of other oddities. (By the way, here is how to reach Nest Support. I’ve been able to get someone on online chat in seconds at any time of day/night. It seems phone support has more limited hours, but would be much faster once you get someone, as the typing response delays and (deliberate?) misunderstandings and nonsense steps through online chat are S L O W.)

To cut to the chase, here’s how we found the device and here’s how to solve an insane problem like this. I call it the nuclear option and next time I’ll just implement it myself. It’s a bit of a pain, but way faster than waiting for tech support to reach the same conclusion.

Google Nest Protect Nuclear Option

Remove all Nest Protects from your system (a.k.a., your “Home” in the Nest app).

Delete your “Home” in the Google Home app.

Create a new Home in your Nest app. (I can’t find a link for this, but it’s pretty easy. There’s a “+” in the Nest app and you click on that.)

Factory reset every Nest Protect. (Any device that won’t factory reset is faulty. Contact Google Nest for replacement.)

Add the Nest Protects to your new Home. Here it is super handy to have pics of the QR codes. (Remember when I told you to do this?!?!) With those, you don’t have to remove them from ceilings.

I would guess I could accomplish all that in about 10 minutes. Instead, I spent over 2 hours with tech support.

Pro tip to Google Nest tech support: You could be a lot better. When the data from the customer makes no sense (smoke detection signals that don’t exist, simultaneous low battery warnings that make no sense), just jump to the nuclear option. Chasing each individual problem doesn’t work. It’s a systemic corruption only a full recreation of the Home and factory reset will solve.

Thank goodness I was home when all this happened. I shudder to think how much difficulty my family would have troubleshooting this without me (I’m the tech guy). And, had we all been out, would the neighbors have eventually called the fire department and have our door beaten in … for nothing?

The post Nest Protect and the nuclear option first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

December 7, 2020

Religion and COVID: at odds?

Elsa Pearson, MPH, is a senior policy analyst at Boston University School of Public Health. She tweets at @epearsonbusph.

Two weeks ago, the Supreme Court ruled against New York’s most recent COVID-19-related restrictions on houses of worship, a win for religious freedom. But was it also a loss for public health?

The tensions between religious freedom and public health were high at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and are on the rise yet again as we enter the holiday season.

COVID-19 made church as we know it difficult, if not impossible. As Massachusetts prepared to lift the COVID-19 lockdown in May, over 250 pastors urged the governor to include churches in the first phase of reopening. Some clergy argued that religious organizations are essential businesses and should be opened quickly. (The governor did honor this and included churches in phase one.)

“Churches are absolutely essential,” said Clay Myatt, a pastor in Brockton, Massachusetts. “We offer community, justice, and, perhaps above all, hope during crisis.”

Plus, we have a constitutional right to religious expression. (To this end, some churches have deliberately defied gathering restrictions.) Stay-at-home orders – though justified as states sought to protect their residents’ health – seemed at odds with the freedom to worship.

Religious freedom and public health don’t have to be in conflict, but they may require a bit of give and take.

Religious participation has many benefits. It’s been associated with both improved mental health (such as increased self-esteem and hope) and improved physical health (such as lower blood pressure, cigarette use, and mortality). Many churches also provide food and financial assistance, even health screenings and disaster relief.

Unfortunately, there is risk associated with in-person activities like religious services. Large indoor gatherings are perfect for spreading COVID-19 and there are many examples of outbreaks in churches that ignored the warnings. But the risk of infection is not insurmountable.

In the short term, these physical and psychological benefits can be – and have been – provided through virtual gatherings and contactless delivery methods (similar to how the health care system is responding through telehealth). The pandemic forced churches to create community and meet needs in novel ways; nationwide, they implemented outdoor services, capacity limits, social distancing, and mask use. Accepting these justified restrictions gave parishioners the opportunity to exercise their constitutional rights safely.

If religious leaders care for their congregants’ spiritual and emotional health, it’s fair to say they care for their physical health, too. R. Steven Warner, another Brockton pastor, agreed, arguing that caring for our physical health is biblical, or required. Taking extra precautions during the pandemic is just another way to do that.

In the long term, however, virtual church is not sustainable. Separation from our spiritual homes takes a significant toll, not mention the constitutional concerns. As we approach the holiday season full of religious celebrations, how do we balance both religious freedom and the public’s health?

In a word, cooperation. In another, compromise.

Religious leaders must prioritize the health of their congregations with stringent cleaning and safety protocols. Full compliance with COVID-19 guidelines will respect the value of religious expression while still protecting the congregation’s health.

At the same time, public health and government leaders must prioritize the spiritual health of their communities by keeping churches open when possible. Initial stay-at-home orders were justified and necessary but many would have viewed any further delay to reopening churches as a violation of constitutional rights. Future shutdowns will likely be viewed the same way. Local leaders would be remiss to ignore this; there is a clear need for spiritual connection during these difficult times.

Thankfully, it doesn’t have to be a dichotomy; we don’t have to choose between religious freedom and public health. In principle, the two are not at odds, said Myatt. “It’s true that certain religious freedoms have recently been curtailed for the sake of health and safety. But other freedoms have been, too.”

Finding the right balance, though, will require respect for both our physical and spiritual needs. That balance is dynamic, too. At the beginning of the pandemic, public health trumped religious freedom with little objection. Over the summer, the two lived in relative harmony after state and local leaders acknowledged the need for in-person religious expression. Now, as cases keep rising, the pendulum may swing back in favor of public health.

Should that happen, frustrations about the infringement on constitutional rights will also rise. The battle for separation of church and state will have sudden fuel, and “be sure that religious freedom will win in court, while the country loses in health and safety,” said Warner.

That warning means we must do this right; we must honor both health and spirituality. If we do, it’ll get us back to the church we know to sooner rather than later. And safely.

COVID-19 isn’t the first threat to harmony between religious freedom and public health and it won’t be the last. The observed discord is rooted in fear. It’s appropriate to fear threats to our constitutional rights and to our health. But protecting one does not require sacrificing the other.

The post Religion and COVID: at odds? first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

December 1, 2020

*Update*: Deadline Extended for Abstracts for HSR Special Issue on International Comparisons of High-Need, High-Cost Patients

Health Services Research (HSR) and the International Collaborative on Costs, Outcomes and Needs In Care (ICCONIC) are partnering to publish a Special Issue on International Comparisons of High-Need, High-Cost Patients: New Directions in Research and Policy. The issue is sponsored by The Health Foundation and the abstract submission deadline has been extended to December 11, 2020. Find more details here.

The post *Update*: Deadline Extended for Abstracts for HSR Special Issue on International Comparisons of High-Need, High-Cost Patients first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

November 30, 2020

Bradykinin Storms and Covid Inflammation

We’re getting close to a year of living with Covid-19, but work is still ongoing to understand the mechanisms behind some of its most devastating effects. A lot of attention has been given to Cytokine Storms in this realm, but with some conflicting evidence there, Bradykinin Storms are starting to share some of the spotlight.

The post Bradykinin Storms and Covid Inflammation first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

November 27, 2020

“So, how do you feel about having cancer during COVID?”

Because The Incidental Economist is widely read, I am frequently interviewed by Canadian journalists (radio, TV, and print). I want to talk about provincial and national health policy. But the interviewer always wants me to say how it feels to have cancer during the COVID pandemic.

Well, it varies. When I was first diagnosed and I learned about my treatment options, it was clear that I had a choice of ordeals. I’ve done ordeals: marathon, triathlon, dissertation. So when the courses of treatment were presented to me, I knew I could do them, and I set about working through the details.

And when I finished radiation therapy, I was elated. Yes, I had lost 30 lbs, my throat was on fire, my neck was swollen with lymphedema, and I was still feeding through a tube. But I was done, over the finish line, and it was going to get better from here. I began planning a recovery — reconstructing my daily writing routine, my low carb/high protein diet, and my weekly yoga/strength/cycling routine. It was my Build Back Better plan.

Those programs have lasted, more or less. I am recovering, I am writing, I’m eating well, and I am exercising. But Build Back Better isn’t how life feels.

Mark Rothko, Untitled, 1969.

On the one hand, there is a depth of fatigue in life that is new to me. There is a blackness, a singularity of exhaustion in my bone marrow, and it laughs at my self-help routines. It will take months of recovery to clear it if it ever entirely goes away.

On the other hand, cognitively and emotionally, I’m not at all sure that things will get better. Cancer brings the reality of death up close and personal.

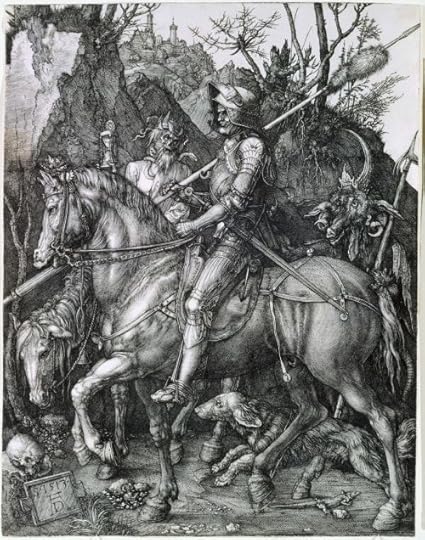

Albrecht Dürer. The Knight, Death, and the Devil. 1513.

When I chose my treatment plan, the deal was that I had a 75% chance of surviving 5 years. Here’s how I understand this: there are 3 chances in 4 that the radiation has destroyed my tumour. If that’s what happened, I now have more or less the longevity of other 67-year-old males. Conversely, there is one chance in four that cancer has disseminated from my throat. Then, my apparently successful radiation therapy will be followed by new cancer. I’ve been through this with friends, and it has killed them.

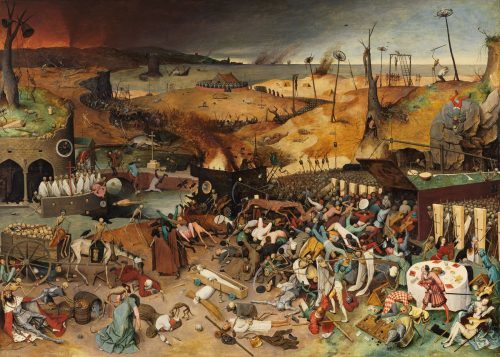

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Triumph of Death. 1562.

Then, add COVID. I’m now in the intersection of two high-risk categories. I disinfect whenever I see a dispenser. I wear a mask whenever I know that I’ll meet people out of the house. But I’m not perfect, and someday, I’m likely to walk through a cloud of droplets. What happens then?

Albrecht Dürer. Melancolia I. 1514.

I don’t obsess about death. I have a purely depressive personality, just the emotional blue notes, without concomitant anxiety. I don’t experience much fear, including fear of death—nevertheless, the actuarial odds condition all my choices. I am always aware that time may be limited.

Vincent Van Gogh. Wheatfield with Crows. 1890.

If not for COVID, we would travel to be with our children in the US. But the border is closed. So the choice is work and that’s fine. What cancer and COVID press me to ask is, “what do I still have to say that might make a difference?”

To read the Cancer Posts from the start, please begin here.

The post "So, how do you feel about having cancer during COVID?" first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

November 25, 2020

Improve Emergency Care? Pandemic Helps Point the Way

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2020, The New York Times Company). It also appeared on page B3 of the print edition on November 24, 2020.

The pandemic may present an opportunity to reshape the future of emergency medicine.

The coronavirus has already prompted health care leaders to rethink how to deliver care to make the most of available resources, both physical and digital. If the shift to greater use of telemedicine continues after the pandemic, it could reduce reliance on the emergency room, where crowding has long been a problem.

This could happen if telemedicine increases the ability for doctors to see more patients more quickly. A Veterans Health Administration study found that same-day access to primary care was associated with fewer emergency visits for conditions that weren’t true emergencies.

During the pandemic, educational campaigns have tried to raise awareness about telemedicine, offering guidelines on when people should seek immediate attention, and when an online consultation is adequate. And American Medical Association officials are seeking to keep the regulatory flexibility on telemedicine that has been allowed during the pandemic.

Of course, telemedicine isn’t a solution for every health problem. And patients with limited digital fluency and access may get left behind as reliance on telemedicine grows. But the potential payoff is large: A review of medical records of older patients found that 27 percent of emergency room visits could have been replaced with telemedicine.

According to the American College of Emergency Physicians, more than 90 percent of emergency departments are routinely crowded, which has long been recognized as problematic.

On average, a patient visiting an emergency room will wait about 40 minutes. Although that’s down from about an hour a decade ago, 17 percent of patients visiting an emergency department in 2017 waited over an hour. About 2.5 percent waited more than two and a half hours.

As many studies have documented, longer wait times can be harmful. For some conditions, a systematic review in 2018 found, longer waits are associated with lower-quality care and adverse health outcomes that include increased mortality. One study found that crowding in the emergency room is associated with a longer wait for antibiotics for pneumonia patients.

“Early antibiotics are critical for a number of common and serious conditions treated in the E.D., including pneumonia,” said Dr. Laura Burke, an emergency physician with the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. “Patients who have delays in antibiotic treatment have higher death rates.”

Another study of nearly 200 California hospitals in 2007 found crowded emergency departments were associated with longer hospital stays, higher costs and a greater chance of death.

This crowding and its adverse consequences are problems in other countries, too. A 2018 National Bureau of Economic Research working paper examined emergency department wait times in England. Beginning in 2004, a policy penalized hospitals if their emergency departments did not complete treatment for the vast majority of patients within four hours, admitting them to the hospital if necessary for subsequent care. Large fines were imposed for failing to meet this target and, in some cases, hospital managers lost their jobs.

The study found that the policy reduced the time a patient spent in the emergency department by 19 minutes, on average, or about 8 percent. It also found a reduction in 30-day mortality of 14 percent and in one-year mortality of 3 percent.

Longer waits can also increase costs, according to a study published last year in Economic Inquiry. A 10-minute-longer wait increases the cost to care for patients with true emergencies by an average of 6 percent. The study took advantage of the fact that emergency department triage nurses make different decisions about how quickly to treat similar patients, which inserts a degree of randomness into their waiting times.

“The longer patients wait, the more their conditions can deteriorate,” said the study author, Lindsey Woodworth, an economist with the University of South Carolina. “Sicker patients cost more to treat.”

A big contributor to crowding, Dr. Burke said, is that some types of patients — in particular those needing behavioral health care — are hard to move out of the emergency department, even when they no longer need to be there. “Many hospitals do not reserve enough beds for behavioral health patients,” she said. “These patients often wait days in the E.D. for definitive care and, by taking up space in the E.D., they delay the E.D. care for other patients.”

Because the bottleneck in this case is the need for more hospital beds for patients with mental health conditions, this is not necessarily a problem that telemedicine can address.

Additionally, many people end up waiting in the emergency department on the advice of other medical providers, though they may not need to. Their problems could be handled elsewhere. Although estimates vary, some studies suggest up to a third of E.D. visits are avoidable.

Although health care coverage has grown since passage of the Affordable Care Act, newly insured people tend not to have a regular source of care like a primary care physician. When health problems arise, those newly insured tend to visit the emergency department, just as they might have before they were covered.

In situations that aren’t true emergencies, urgent care centers or retail clinics may provide faster care. But sometimes the only source of help available in the middle of the night is an emergency room. One study found that when urgent care centers close, emergency room volume increases. It’s worth mentioning that lower-income patients or those without coverage may be unable to afford care at these centers.

Once the pandemic fades, the momentum from telemedicine may continue, with the possibility of making progress on a problem that shouldn’t wait.

The post Improve Emergency Care? Pandemic Helps Point the Way first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

November 24, 2020

Covid-19 is NOT the Flu

One argument we continue to hear about the reaction to Covid-19 is that “it’s just another flu”, and that we can move forward with life as usual, much like we move forward with life during flu season. While we wish that were true, it simply is not. There are major differences that necessitate a much bigger reaction to Covid-19. In today’s episode we detail both the similarities and the differences between the illnesses caused by these two viruses.

The post Covid-19 is NOT the Flu first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

November 19, 2020

Recent publications from Boston University’s Department of Health Law, Policy and Management: November 2020 Edition

Below are recent publications from me and my colleagues from Boston University’s Department of Health Law, Policy and Management. You can find all posts in this series here.

November 2020 Edition

Anderson E, Solch AK, Fincke BG, Meterko M, Wormwood JB, Vimalananda VG. Concerns of Primary Care Clinicians Practicing in an Integrated Health System: a Qualitative Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2020 Sep 11. PMID: 32918198.

Blevins CE, Marsh EL, Stein MD, Schatten HT, Abrantes AM. Project CHOICE: Choosing healthy options in coping with emotions, an EMA/EMI plus in-person intervention for alcohol use. Subst Abus. 2020 Sep 01; 1-8. PMID: 32870129.

Connolly SL, Hogan TP, Shimada SL, Miller CJ. Leveraging Implementation Science to Understand Factors Influencing Sustained Use of Mental Health Apps: a Narrative Review. J Technol Behav Sci. 2020 Sep 07; 1-13. PMID: 32923580.

Crable EL, Biancarelli D, Walkey AJ, Drainoni ML. Barriers and facilitators to implementing priority inpatient initiatives in the safety net setting. Implement Sci Commun. 2020; 1:35. PMID: 32885192.

Dianti J, Matelski J, Tisminetzky M, Walkey AJ, Munshi L, Del Sorbo L, Fan E, Costa EL, Hodgson CL, Brochard L, Goligher EC. Comparing the Effects of Tidal Volume, Driving Pressure, and Mechanical Power on Mortality in Trials of Lung-Protective Mechanical Ventilation. Respir Care. 2020 Aug 25. PMID: 32843513.

Figueroa JF, Wadhera RK, Frakt AB, Fonarow GC, Heidenreich PA, Xu H, Lytle B, DeVore AD, Matsouaka R, Yancy CW, Bhatt DL, Joynt Maddox KE. Quality of Care and Outcomes Among Medicare Advantage vs Fee-for-Service Medicare Patients Hospitalized With Heart Failure. JAMA Cardiol. 2020 Sep 02. PMID: 32876650.

Griffith KN, Ndugga NJ, Pizer SD. Appointment Wait Times for Specialty Care in Veterans Health Administration Facilities vs Community Medical Centers. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Aug 03; 3(8):e2014313. PMID: 32845325.

Gunn CM, Maschke A, Paasche-Orlow MK, Kressin NR, Schonberg MA, Battaglia TA. Engaging Women with Limited Health Literacy in Mammography Decision-Making: Perspectives of Patients and Primary Care Providers. J Gen Intern Med. 2020 Sep 15. PMID: 32935318.

Hawley CE, Genovese N, Owsiany MT, Triantafylidis LK, Moo LR, Linsky AM, Sullivan JL, Paik JM. Rapid Integration of Home Telehealth Visits Amidst COVID-19: What Do Older Adults Need to Succeed? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020 Sep 15. PMID: 32930391.

Hickey E, Sheldrick RC, Kuhn J, Broder-Fingert S. A commentary on interpreting the United States preventive services task force autism screening recommendation statement. Autism. 2020 Sep 14; 1362361320957463. PMID: 32921149.

Huberfeld N, Watson S, Barkoff A. Struggle for the Soul of Medicaid. J Law Med Ethics. 2020 09; 48(3):429-433. PMID: 33021181

Jasuja GK, de Groot A, Quinn EK, Ameli O, Hughto JMW, Dunbar M, Deutsch M, Streed CG, Paasche-Orlow MK, Wolfe HL, Rose AJ. Beyond Gender Identity Disorder Diagnoses Codes: An Examination of Additional Methods to Identify Transgender Individuals in Administrative Databases. Med Care. 2020 10; 58(10):903-911. PMID: 32925416.

Jones DK, Gordon SH, Huberfeld N. Have the ACA’s Exchanges Succeeded? It’s Complicated. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2020 Aug 1;45(4):661-676. PMID: 32186335.

Johnson G, Frakt A. Hospital markets in the United States, 2007-2017. Healthc (Amst). 2020 Sep; 8(3):100445. PMID: 32919591.

Katz DA, Wu C, Jaske E, Stewart GL, Mohr DC. Care Practices to Promote Patient Engagement in VA Primary Care: Factors Associated With High Performance. Ann Fam Med. 2020 09; 18(5):397-405. PMID: 32928755.

Leech AA, Christiansen CL, Linas BP, Jacobsen DM, Morin I, Drainoni ML. Healthcare practitioner experiences and willingness to prescribe pre-exposure prophylaxis in the US. PLoS One. 2020; 15(9):e0238375. PMID: 32881916.

Marques L, Youn SJ, Zepeda ED, Chablani-Medley A, Bartuska AD, Baldwin M, Shtasel DL. Effectiveness of a Modular Cognitive-Behavioral Skills Curriculum in High-Risk Justice-Involved Youth. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2020 Sep 17. PMID: 32947449.

Miller EA, Huberfeld N, Jones DK. Pursuing Medicaid Block Grants with the Healthy Adult Opportunity Initiative: Dressing Up Old Ideas in New Clothes. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2020 Sep 16. PMID: 32955558

Motavalli D, Taylor JL, Childs E, Valente PK, Salhaney P, Olson J, Biancarelli DL, Edeza A, Earlywine JJ, Marshall BDL, Drainoni ML, Mimiaga MJ, Biello KB, Bazzi AR. “Health Is on the Back Burner:” Multilevel Barriers and Facilitators to Primary Care Among People Who Inject Drugs. J Gen Intern Med. 2020 Sep 11. PMID: 32918199.

Nevedal AL, Reardon CM, Jackson GL, Cutrona SL, White B, Gifford AL, Orvek E, DeLaughter K, White L, King HA, Henderson B, Vega R, Damschroder L. Implementation and sustainment of diverse practices in a large integrated health system: a mixed methods study. Implement Sci Commun. 2020; 1:61. PMID: 32885216.

Ohrtman EA, Shapiro GD, Wolfe AE, Trinh NT, Ni P, Acton A, Slavin MD, Ryan CM, Kazis LE, Schneider JC. Sexual activity and romantic relationships after burn injury: A Life Impact Burn Recovery Evaluation (LIBRE) study. Burns. 2020 Sep 15. PMID: 32948357.

Robinson SA, Wan ES, Shimada SL, Richardson CR, Moy ML. Age and Attitudes Towards an Internet-Mediated, Pedometer-Based Physical Activity Intervention for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Secondary Analysis. JMIR Aging. 2020 Sep 09; 3(2):e19527. PMID: 32902390.

Shafer PR, Dusetzina SB, Sabik LM, Platts-Mills TF, Stearns SC, Trogdon JG. Insurance instability and use of emergency and office-based care after gaining coverage: An observational cohort study. PLoS One. 2020; 15(9):e0238100. PMID: 32886675.

Stein MD, Phillips KT, Herman DS, Keosaian J, Stewart C, Anderson BJ, Weinstein Z, Liebschutz J. Skin-cleaning among hospitalized people who inject drugs: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2020 Aug 23. PMID: 32830383.

Stevenson BL, Blevins CE, Marsh E, Feltus S, Stein M, Abrantes AM. An ecological momentary assessment of mood, coping and alcohol use among emerging adults in psychiatric treatment. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2020 Aug 27; 1-8. PMID: 32851900.

Sullivan JL, Engle RL, Shin MH, Davila H, Tayade A, Bower ES, Pendergast J, Simons KV. Social Connection and Psychosocial Adjustment among Older Male Veterans Who Return to the Community from VA Nursing Homes. Clin Gerontol. 2020 Aug 27; 1-10. PMID: 32852256.

Swamy L, Mohr D, Blok A, Anderson E, Charns M, Wiener RS, Rinne S. Impact of Workplace Climate on Burnout Among Critical Care Nurses in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Crit Care. 2020 09 01; 29(5):380-389. PMID: 32869073.

Timko C, Chatav Schonbrun Y, Anderson B, Johnson JE, Stein M. Perceived Substance Use Norms Among Jailed Women with Alcohol Use Disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2020 Sep 02. PMID: 32876998.

Vail EA, Shieh MS, Pekow PS, Gershengorn HB, Walkey AJ, Lindenauer PK, Wunsch H. Use of Vasoactive Medications after Cardiac Surgery in the United States. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020 Sep 14. PMID: 32926642.

Vimalananda VG, Meterko M, Solch AK, Qian S, Wormwood JB, Greenlee CM, Smith CD, Fincke BG. Coordination of Care as Experienced by the Specialist: Validation of the CSC-Specialist Survey in the Private Sector and the Effect of a Shared Electronic Health Record. Med Care. 2020 Sep 10. PMID: 32925459.

Yakovchenko V, DeSotto K, Drainoni ML, Lukesh W, Miller DR, Park A, Shao Q, Thornton DJ, Gifford AL. Using Lean-Facilitation to Improve Quality of Hepatitis C Testing in Primary Care. J Gen Intern Med. 2020 Sep 15. PMID: 32930938.

The post Recent publications from Boston University’s Department of Health Law, Policy and Management: November 2020 Edition first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

November 16, 2020

Becoming Homebound

The following is cross-posted at Public Health Post and is by Katherine Ornstein, PhD, Melissa Garrido, PhD (@GarridoMelissa), and Katelyn Ferreira, MPH. Dr. Ornstein is Director of Research for the Institute for Care Innovations at Home at Mount Sinai and Associate Professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Dr. Garrido is Associate Director of

the Partnered Evidence-based Policy Resource Center (PEPReC) at the Boston VA Healthcare System, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, and a Research Associate Professor at Boston University School of Public Health. Ms. Ferreira is a Research Program Manager at Mount Sinai.

The Covid-19 pandemic has resulted in millions of Americans becoming homebound — having limited social contacts and accessing medical care, groceries, and other needs from within their homes. But for many older Americans, being homebound (i.e., never or rarely leaving home) is already the norm. Our previous work estimated that, in 2011, two million older Americans were homebound—more than the number of people who live in nursing homes.

Homebound adults often have multiple chronic illnesses, difficulties with activities like bathing and dressing, high rates of depression, and few people on whom they can rely for assistance. They also have a higher risk of death than non-homebound individuals with similar characteristics. The practical realities of being homebound, like difficulty accessing routine medical care and inability to engage in valued activities, may contribute to poor outcomes.

Yet there is limited research examining what factors contribute to becoming homebound. In particular, we do not know what social and economic factors lead to becoming homebound. To fill this gap, our team conducted a study examining the association between income and becoming homebound. We used nationally representative data from the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS), an annual survey of adults 65 or older. We looked at participants’ annual household income during the first year of NHATS (2011), and we divided the range of responses into quartiles (< $15,003, $15,004-$30,000, $30,001-$60,000, > $60,000). We then followed non-homebound participants for seven years (2011-2018) to see whether they became homebound.

Participants with higher incomes were less likely to become homebound. In the seven-year study period, 15.81% of older adults in the lowest income quartile became homebound, compared with 11.31% in the next lowest quartile, 6.88% in the second highest, and only 4.64% those in the highest. Membership in the lowest quartile continued to predict homebound status even after accounting for demographics, health status, having a caregiver, and other events (nursing home placement and death).

There are several potential explanations for this relationship. Lower-income older adults may be more vulnerable to the diseases, impairments, and disabilities that lead to becoming homebound. They may also be less likely to have resources for accommodating or overcoming these disabilities. For example, people with lower incomes might not be able to afford assistive devices (like electric wheelchairs) or home modifications (like ramps) that would help them be able to leave their homes.

This evidence that income can help predict who may become homebound is useful for prevention and for meeting the needs of people who are already unable to leave their homes. In the context of wide income disparities in the United States, programs that provide equipment, home modifications, caregiver support, and other assistance for individuals of low or mid-range incomes may allow those individuals to leave their homes more often and avoid becoming homebound.

People who do become homebound must have access to the care and resources they need. Alongside home-based medical care and interventions like Community Aging in Place – Advancing Better Living for Elders (CAPABLE), remote options for healthcare delivery — including telehealth and video visits — can help meet the needs of this population. While the Covid-19 pandemic has led to massive strides in remote-care delivery, we must ensure that the concerns of homebound patients regarding telemedicine are addressed and that they are not left behind as healthcare changes. As health professionals, we need to collaborate in new and creative ways with entities that provide broadband, design assistive technology, and promote digital literacy. Efforts to connect homebound people with health-promoting resources could help not only to address their medical needs, but also to facilitate their social engagement and participation in valued life activities.

The post Becoming Homebound first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

Winter is coming

Will Raderman is a Research Fellow in the Department of Health Law, Policy & Management at the Boston University School of Public Health. He tweets at @RadWill_.

Julia Raifman is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Health Law, Policy & Management at the Boston University School of Public Health and runs the COVID-19 State Policy Database to inform research on social policies and health during the COVID-19 pandemic. She tweets at @juliaraifman.

As temperatures drop and COVID-19 cases rise, millions of Americans are in dire circumstances. President-Elect Biden draws attention to more than 242,000 empty chairs at dinner tables due to COVID-19; another 24 million people lack food on the plates in front of them and 11.5 million renters fear evictions in which they and their dining tables will be thrown onto the street.

While Biden has begun laying out plans for economic relief, any effort started January 21st will come too late for millions of people who lost work during the pandemic through no fault of their own. There is a need for Congress to act now and for the incoming Biden administration to lead comprehensive unemployment insurance (UI) reform.

Only a fraction of jobless workers are receiving unemployment insurance. For millions fortunate enough to receive UI benefits for an extended period during the pandemic, delays in processing have been devastating, and benefits are set to expire in December. Unemployment in the COVID-19 recession is concentrated in lower-income households with little savings and remains elevated as we approach the winter months. Now, millions face economic precarity as they stand to lose crucial unemployment benefits. It doesn’t need to be this way.

US unemployment insurance excludes many

In 2019, just 1 in 10 jobless Americans received state unemployment benefits. Strict requirements to qualify frequently exclude part time, gig, self-employed, and contracted workers, as well as perpetuate racial disparities. It is also difficult for workers who have not accumulated enough income to qualify.

Millions of American workers ineligible for state UI are currently enrolled in the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program funded by the CARES Act, which also provided stimulus checks, increased UI amounts by $600 per week until July, and expanded benefit durations through the Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC) program. Economic insecurity already increased after the $600 per week supplement ended. The expiration of PUA and PEUC in December will cut off millions of families in the depths of winter.

American unemployment insurance benefits are brief

When Americans do qualify for UI, it expires quickly, limiting how many unemployed workers are enrolled. While COVID-19 has been spreading in the US for over 32 weeks, most states provide benefits for 26 or fewer weeks. People often remain unemployed for longer.

Most states have activated Extended Benefits (EB), an additional 13 to 20 weeks of UI in times of high unemployment, but there are 12 states without activated EB. People who lost employment in 2019 as well as residents in states without EB or with short benefit periods are starting to exhaust eligibility.

Thirty percent of U.S. workers displaced from long term jobs between 2017-2019 were still looking for employment in January 2020. Many families like those, out of work prior to the pandemic, may be without UI this winter unless benefit length is expanded further, as it was in many states during the Great Recession.

The US benefit size is small

In all US states, the minimum benefit amount is below the federal minimum wage. Only 28 states have an average benefit above $300 weekly. Furthermore, UI covers an average of just 40% of prior wages, making it difficult for people who lose work to continue paying their essential bills.

Congress increased UI benefits by $600 per week from March to July, briefly matching or exceeding prior wage levels. The $600/week supplement was associated with reduced food insecurity, reduced financial insecurity, and reduced poverty without resulting in lower employment. When supplemental benefits expired in July, unemployment payments returned to substantially lower levels, and many struggled to make ends meet.

Other countries have more expansive unemployment insurance

Meanwhile, other countries consistently cover more people, for longer, and with larger benefits.

Nations with expanded UI often have a broader “scope of eligibility”, including for new workers. The US covers less than half the proportion of jobless people relative to the average OECD country and just a fifth of what some countries cover.

Unemployment insurance also lasts for longer in other countries, where benefits can be claimed for several years, often with a second round of protection called unemployment assistance.

Likewise, the portion of an American’s prior wage replaced by unemployment insurance is rarely equal to the amounts provided elsewhere. This disparity has widened during the pandemic, as some countries cover 80% of former salary levels and are extending those programs.

The need to nationalize US unemployment insurance

In the past several decades, many states have adopted a “pay-as-you-go” approach of funding UI programs solely for the present moment instead of preparing for future instability. State taxes funding UI focus on less than $20,000 of earnings on average, allowing coverage for immediate benefit payments, but leaving states vulnerable to periods of high unemployment when many more people require UI. Underfunding has led many states to reduce UI benefit generosity in both amount and duration.

This weak financing structure is also regressive, with low-income workers dedicating a greater proportion of their earnings to UI insurance than higher-income workers.

These funding structures left states unprepared for the Great Recession and in even more precarious situations now. The federal government stepped in to provide additional financial support during the recession and the pandemic, demonstrating the effectiveness of a nationalized unemployment system for ensuring broader access to benefits.

Nationalizing the UI system could streamline its administration, making it more cost effective and easier to deliver to people who need it, like Social Security. Lengthy application processing times may be reduced. Unemployment benefits could be adequately funded and expanded to be worker-friendly, supporting at-risk families unable to access benefits now, with a greater amount, and for a longer period.

The approaching crisis can be stopped

Millions of Americans are at risk of even more intense and enduring economic and emotional damage than that seen during the Great Recession, when millions of families lost their homes and suicide rates went up. Congress can and should prevent this by expanding UI now.

As the Biden-Harris administration plans to Build Back Better from COVID-19, reforming the UI system must be a key priority. The US can implement a permanent, federally funded UI system that is easy to administer. The UI system can be modernized to cover more workers, including those in the Gig economy. It can guarantee a living wage and provide an amount similar to prior earnings, as well as cover people for a longer duration. This is what the majority of OECD countries do. By strengthening unemployment insurance, we can help families weather the winter in their homes, eating dinner around their dining tables.

The post Winter is coming first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers