Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 49

September 4, 2020

Rethinking Testing for Covid-19

PCR tests for Covid-19 are pretty accurate, but supplies can be scarce and results sometimes aren’t available in time to be useful. Faster tests are available, but are less accurate, so some have argued against their use. We disagree because, in a pandemic, frequency and speed of testing matter more than pinpoint accuracy. As we try to reopen schools and businesses we need to take a hard look at how we’re conducting testing.

The post Rethinking Testing for Covid-19 first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

September 2, 2020

Childcare During a Pandemic

Zoe Bouchelle, MD, is a Pediatrics Chief Resident at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Irit Rasooly, MD, MSCE, is pediatric hospital medicine physician and researcher in the Departments of Pediatrics and Biomedical & Health Informatics at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and a fellow of Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine in Diagnostic Excellence. Tara Bamat, MD is an attending physician in the Division of General Pediatrics and Hospice and Palliative Medicine and Associate Program Director of the Pediatric Residency Program. Barbara Chaiyachati, MD,PhD, is a fellow physician in the section of Child Abuse Pediatrics at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to widespread disruption in childcare, including school and daycare closures. While limiting congregation in childcare is an important policy for promotion of social distancing and reduction of viral transmission, it does not come without costs. For young children, in pre-pandemic times, the majority of children under 6 lived in households with all working parents and the shuttering of daycares created an immediate care need for millions of families. For school-aged children, school closures brought concerns about worsening health disparities, educational inequalities, and mental health. For adults, school closures made work challenging (both in-person and remotely) and the new need for in-home childcare could be an added economic burden for millions of families. As pediatricians and mothers working through the pandemic, we worry about the impacts of childcare and school closures on our patients and our children – and ourselves.

Inadequate Childcare

To better understand childcare challenges early in the pandemic, we conducted a survey of parents about childcare access. We recruited a convenience sample of adult (≥18 years) parents of children

We found that among the 469 respondents, 301 (64.8%) reported having an essential worker in their household, including 214 (45.6%) healthcare workers. Among essential workers, we found that 79% indicated experiencing a change in childcare with the pandemic, 32% reported less consistent childcare, and almost 8% reported paying at least $500 more per month on childcare. Single parent households and those working in healthcare were less likely to report care for children at home with only immediate household members. These findings underscore the dramatic impact school and daycare closures had on essential workers during the pandemic.

Impact of Inadequate Childcare and Working Parents

There are important consequences of inadequate childcare for working parents that can be drawn from our results including the inherent challenges of going back to work, concerns about the safety and stability of available childcare, and the potential for disproportionate impact on working mothers. We highlight some of these consequences below but it’s important to note that many of these challenges predated the pandemic as part of a broader childcare crisis in the US, and are only underscored by the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, these challenges will likely be exacerbated in the aftermath of COVID.

Parents’ ability to work is critical to ensure already existing socioeconomic disparities do not widen. In pre-pandemic times, almost 20% of children in the U.S. were already living in poverty. During the pandemic, many families suffered lost work, likely placing even more families at risk of poverty. While some families may have been financially buoyed intermittently by stimulus relief and increased federal unemployment, allowing them to care for children safely at home, that benefit has now lapsed and childcare costs must be recognized in return to work calculations.

We also must ensure that families do not need to put children in physical danger in order to return to work. Without support for safe and adequate childcare, working parents may resort to leaving younger children in the care of older siblings or in the care of someone they do not fully trust. Children without appropriate oversight are at risk of injury. For example, we have seen that there has been a 30% increase in accidental shooting deaths by children from March-May 2020 compared to the same period in 2019, a spike in pediatric poisonings and dog bites, and concentration of avoidable harm in emergency departments since the onset of the pandemic.

Additionally, families need access to care that minimizes risk of COVID exposures. Leaving children in the care of a rotating cycle of caregivers increases children’s risk of exposures and continues to put children and communities at risk. Based on our results early in the pandemic, some essential workers who were most critically needed to report to work in person – healthcare workers – were less likely to report care for children at home with only immediate household members. Unfortunately, unabating risk at work and home may lead to a shortages in the healthcare workforce.

Finally, there is increasing concern that childcare shortages and shifting work demands related to the pandemic could disproportionately disadvantage working women and have long-term repercussions on gender equality. Among married couples who work full time, there is evidence that women provide close to 70 percent of childcare during standard working hours. A survey by Boston Consulting Group during the pandemic found that parents now report spending 27 additional hours each week on domestic duties, with women spending 15 hours more each week than men. The shifting demands of work and home life and the looming “Greater Recession” negatively impact all workers, but will likely disproportionately affect working mothers. This could have long-term impacts on the percentage of women in the labor market.

Taking Action Through Policy

With millions of children out of school and daycare, we are experiencing a national childcare crisis. As we move into the fall and expect that many schools and daycares will not fully reopen, policymakers and employers must advocate for and invest in policies that provide financial, housing, and food assistance to struggling families, keep children safe at home while allowing families to return to work, and provide proactive support for working parents, particularly mothers, who are at risk of being disadvantaged and excluded from reentry into the labor market.

During this unprecedented time, struggling families and children deserve adequate, stable, comprehensive support from their governments and employers.

The post Childcare During a Pandemic first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

August 31, 2020

Spotlight on Naloxone Co-Prescribing

This is a guest post by Adm. Brett Giroir, Jessica White, Teresa Manocchio, Sean Klein, Zeid El-Kilani. Adm. Brett Giroir is the 16th Assistant Secretary for Health (@HHS_ASH) at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Jessica White, Teresa Manocchio, Sean Klein, and Zeid El-Kilani work for the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (@HHS_ASPE) at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

As we recognize International Overdose Awareness Day, HHS is calling attention to the co-prescription of naloxone, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved medication that can save a person’s life when administered during an opioid overdose. Naloxone is available in three formulations – nasal spray, injectable, and auto-injector – and at least one form of naloxone is covered by most health insurance plans, including Medicaid and Medicare.

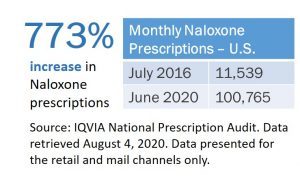

Since July 2016, prescriptions for naloxone in the U.S. have increased 773%. Expanding the availability and distribution of overdose-reversing drugs is one of the five pillars of HHS’s comprehensive, science-based strategy for combatting the opioid overdose epidemic. These efforts include co-prescribing naloxone in conjunction with an opioid prescription, or prescribing naloxone to at-risk individuals.

As of July 2020, the FDA announced it is requiring changes to the prescribing information for opioids and medications to treat opioid use disorder (OUD). These changes include recommending that as a routine part of prescribing these medications, health care professionals should discuss the availability of naloxone with patients and caregivers, both when beginning and renewing treatment. Additionally, they should consider prescribing naloxone based on a patient’s risk factors for overdose. Previously, in December 2018, HHS released guidance for health care providers and patients detailing how naloxone should be prescribed to all patients at risk for opioid complications, including overdose. Naloxone co-prescribing is also recommended in the 2016 CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain.

Over the past several years, a growing number of states have implemented laws and regulations requiring health care providers to co-prescribe naloxone with opioid prescriptions to patients considered at risk of an overdose. As HHS regularly tracks the number of naloxone prescriptions dispensed in the US within mail order and retail pharmacies, we are greatly encouraged by continued increases in naloxone prescriptions, particularly within states that have recently implemented naloxone co-prescribing legislation.

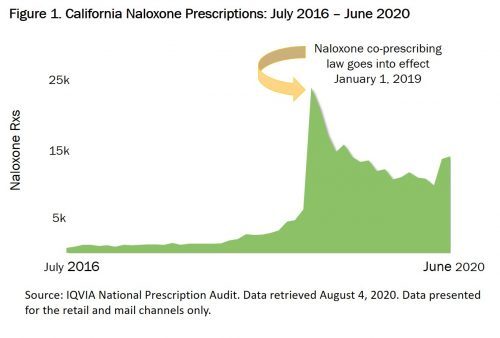

For example, a California law effective January 1, 2019, requires that prescribers offer a prescription for naloxone when certain conditions are met, including high daily doses of opioids, concurrent opioid and benzodiazepine prescriptions, and increased risk of an opioid overdose (e.g. a patient with a history of OUD or previous overdose). Prior to the effective date of the law, naloxone prescriptions averaged approximately 1,800 monthly. In the first month following the effective date of the law, naloxone prescriptions jumped 282% (Figure 1) and have averaged approximately 13,800 monthly since.

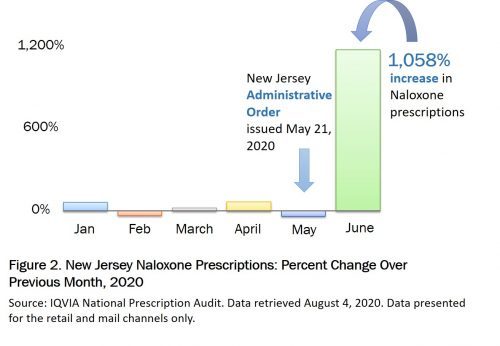

Recent mail order and retail pharmacy data from New Jersey reflect similar trends. An administrative order issued on May 21, 2020 directs practitioners to prescribe naloxone for any individual receiving high daily doses of opioids or concurrent opioid and benzodiazepine prescriptions. Even during a pandemic, naloxone co-prescribing laws lead to increased naloxone prescriptions. Data from June 2020 show an increase in naloxone prescriptions in New Jersey of 1,058% over May (Figure 2).

Although the number of naloxone prescriptions is not necessarily representative of naloxone use or decreasing opioid overdose deaths, naloxone continues to play an important role as one pillar of our comprehensive strategy to address the opioid crisis.

The post Spotlight on Naloxone Co-Prescribing first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

August 26, 2020

Blood Types & Covid-19

There’s been a lot of discussion about differences in susceptibility and symptom severity among people with different blood types. Does your blood type determine how likely you are to contract COVID-19 and/or the severity of your case? We’re looking at some initial data to see how this idea holds up.

The post Blood Types & Covid-19 first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

The Fine Line Between Choice and Confusion in Health Care

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2020, The New York Times Company).

American opponents of proposed government-run health systems have long used the word “choice” as a weapon.

One reason “Medicare for all” met its end this year has been the decades-long priming of the public that a health system should preserve choice — of plans and doctors and hospitals. To have choice is to be free, according to many.

So how many Americans actually have choices, and what type of freedom do choices provide?

Making mistakes with Medicare

Current Medicare enrollees have more choices than any other Americans — to some, in fact, an overwhelmingly large number of them.

In 2019, 90 percent of Medicare enrollees had access to at least 10 Medicare Advantage plans, which are government-subsidized, private-plan alternatives to the traditional public program.

But this is just the beginning. If Medicare beneficiaries who elect to enroll in the traditional public program want drug coverage, they must choose from large numbers of private prescription drug plans. In 2014, beneficiaries could choose from an average of 28 drug plans. They can also select private plans that wrap around traditional Medicare, filling in some of its gaps, and this doesn’t even count plan options that may be available through former employers as retiree benefits.

Choosing among all these options would be a challenge for anyone, or, as a Kaiser Family Foundation report put it, “a daunting task.”

“Medicare beneficiaries are so confused, overwhelmed and frustrated with the number of choices and the process of choosing among them, they end up taking shortcuts,” said Gretchen Jacobson, now with the Commonwealth Fund and an author of the report. “Those shortcuts can lead them to select plans that aren’t as beneficial to them as other options.”

In other words, freedom to choose is also freedom to make mistakes.

For instance, in the first year that drug plans were available to Medicare beneficiaries, economists have shown that 88 percent of them chose a more costly plan than they could have. This cost them 30 percent more, on average, and the tendency to select needlessly costly plans persisted in subsequent years. This is the kind of error, as other studies have found, that is easy to make when inundated by choices.

More generally, without some assistance, many people don’t understand the health insurance choices and features. Even common terms can be confusing. In one study, all the subjects said they understood what a “co-pay” was, but 28 percent could not answer a question testing their knowledge of the term; 41 percent couldn’t define what “maximum out-of-pocket” meant.

Of course, just because people make mistakes when faced with choices doesn’t imply that a single plan for all would be a better fit for more people. It all depends on the details.

Medicaid also offers the vast majority of enrollees private-plan choices. States, on average, offered seven plans for enrollees to choose from in 2017. Some types of enrollees — particularly those with more complex health problems — are not able to choose plans and are put into one that specializes in their needs.

According to a systematic review by Michael Sparer, a professor at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, studies do not find much cost savings to Medicaid programs stemming from all this choice. But some studies indicate that private Medicaid plans do provide better access to some types of care, including primary care.

A caution, however: “Since Medicaid is a state-based program, broad averages don’t tell you much about what is happening in specific states,” he said. “Some states have been able to save money through the managed care options enrollees can select, and some have not.”

It’s much less clear how many choices people with employer-sponsored plans have, because that data isn’t public. Generally speaking, employers serve as a filter, selecting or working with insurers to devise a small number of plans offered to employees.

What we do know is that three in four employers offer just a single plan. These are mostly small businesses, so only a minority of workers are employed by them. Most workers (64 percent) are employed by firms that offer some choice among plans. But most of these workers are at firms that offer just two options. Does this imply workers at these firms have less freedom?

About 4 percent of firms with more than 50 employees offer coverage in private exchanges, akin to what the Affordable Care Act established for individuals. “Private exchanges generated a lot of hype five years ago,” said Paul Fronstin, director of health research at the Employee Benefit Research Institute. “For some reason, they just never became popular.”

He gets his coverage from an exchange that offers a whopping 60 plans. “Choosing among them is no small task, particularly because information about them is so confusing,” he said.

One employer that stands out in offering choices is the federal government. Federal employees can typically choose from about two dozen plans (the number and details vary by state). There are 28 plans in Washington and 21 in Rhode Island, for example.

This year, all A.C.A. marketplace enrollees have choices among plans, on average about 19 of them. Some have over 100.

All told, a rough calculation suggests that about 80 percent of insured Americans have a choice of health plan.

What is ‘freedom’ in health care?

It’s worth considering what accompanies health insurance choice for some Americans. If you work at a company, you could lose access to affordable coverage if you lose your job or if the company decides to stop offering it.

Other people choose coverage plans that can be too skimpy to pay for a major treatment.

Yet others may have options, but they may not be affordable. None of this is necessarily a condemnation of choice per se, just the nature of health insurance choice in America today.

Medicare for all was supposed to address problems like these. As the Finnish author Anu Partanen wrote of a single-payer system: “The point of having the government manage this complicated service is not to take freedom away from the individual. The point is the opposite: to give people more freedom.”

The Medicare for All Act would have offered no choice, enrolling everyone in the same, comprehensive plan with no out-of-pocket cost. Proponents of this approach trust the government to devise a program suitable for all. Detractors of it favor choices precisely because they have less faith that government will do a better job than plans that are in competition. For them, freedom to choose is freedom from tyranny. But too much choice without enough guidance can be overwhelming.

The post The Fine Line Between Choice and Confusion in Health Care first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

August 25, 2020

While the US is reeling from COVID-19, the Trump administration is trying to take away health care coverage

Paul Shafer is an assistant professor of health law, policy, and management at the Boston University School of Public Health. Nicole Huberfeld is a professor of law and health law, policy, and management at the Boston University Schools of Law and Public Health. Follow them on Twitter at @shaferpr and @nhuberfeld1.

The Trump administration has had its hands full responding to the coronavirus pandemic, but that hasn’t stopped it from taking steps to reverse much of the gains in health insurance coverage since the Affordable Care Act was passed in 2010. In an article today on The Conversation, we discuss two major actions by the Trump administration that may would typically have made huge headlines but may have gotten lost in the COVID shuffle – 1) attempting to block grant Medicaid and 2) supporting a Supreme Court case that could take down the ACA.

Despite shaky legal footing, the administration has moved ahead with its Healthy Adult Opportunity guidance, issued to state Medicaid directors in January, that allows for states to opt-in to a per capita cap or program-level block grant for Medicaid. Oklahoma was going to be the first to implement this until a ballot initiative to expand Medicaid passed in July.

Block granting Medicaid has been a goal of Republicans for years, including during the ACA repeal efforts in Congress, but has never been able to be passed into law. This end run around federal law has been loudly challenged by legal scholars but is only one plank of the administration’s plans.

Texas v. California will be heard in November, a case in which 17 Republican-led states are trying to take down the ACA through again dubious legal arguments about severability of the individual mandate from the rest of the law. The administration has abdicated its role to defend the law and is arguing in favor of striking it down, trying to accomplish through the courts what it has failed to do through Congress.

As we wrote,

If the ACA is struck down, that means the loss of coverage for preexisting conditions, the return of annual or lifetime caps, or policies being revoked for cancer patients. Those who don’t earn much money still deserve good health care. Nearly everyone will feel it if the Trump administration and Texas are successful, regardless of whether your health insurance is through your work, HealthCare.gov, Medicaid or Medicare.

This fall, the Supreme Court and the voters will have a lot to say about how access and affordability of health insurance coverage look in 2021 and beyond.

Read the whole piece here.

Research for this piece was supported by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation.

The post While the US is reeling from COVID-19, the Trump administration is trying to take away health care coverage first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

August 21, 2020

The Opioid Crisis and the Way Forward

This is part 4 in our series on the opioid crisis, presented with support from the NIHCM Foundation. We’ve talked about the state of the opioid crisis, deaths of despair, and the disappointing evidence about marijuana as a treatment for opioid dependence. But the outlook doesn’t have to be entirely bleak. In this final episode, we zero in on where we’re still failing and what the data are telling us to do.

August 18, 2020

Can Marijuana Help with Opioid Addiction?

Part 3 of our opioid series, supported by the NIHCM Foundation, examines the potential of marijuana to improve outcomes in opioid addiction therapy. Some studies have suggested that marijuana can ease the path to shaking opioid dependence, but more recent data might be telling us a different story.

August 14, 2020

Confronting Structural Racism

The following originally appeared on the Drivers of Health blog.

Earlier this month, I participated in a plenary panel on confronting structural racism in health services research at the AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting. I believe most of what I said generalizes outside of this field of research. My opening comments are below, and I was joined on the panel by Don Taylor and Sherilynn Black (Professor and Associate Vice Provost for Faculty Advancement, respectively, at Duke University), Linda Blount (President and CEO of the Black Women’s Health Imperative), and Steven Brown (a Research Associate at the Urban Institute).

As a discipline, health services research is in its sixth decade. That means it grew up in the context of racist laws, practices, and policies. It is not possible for HSR’s institutions and scholarship to have avoided racism’s influence. Let us at least accept this fundamental truth.

Structural racism is all around us, even if we are blind to it. It used to be popular to say one is color blind. But, at least for me, that equated to a lack of attention to racism. I didn’t see it because I didn’t look for it. For a long time I was satisfied with that. But it’s not satisfactory.

There is an unsatisfactory complacency that emerges from believing not being racist is adequate. It’s not adequate. In truth, it’s a passivity that tacitly supports structural racism everywhere, including in HSR. That I was not racist was merely a story I told myself. It didn’t have any impact on my community or the institutions where I work.

This reflects the unjustified and unjustifiable privilege of whiteness. As a white person, I have a privilege to be able to walk away from racism, to not think about it, to not have it contribute to my daily life — in a way that my Black colleagues cannot.

Change for myself, for HSR, and other areas, will require rejecting this privilege. I and my white colleagues have to find ways to challenge ourselves daily in the project of anti-racism. There’s a reason we’re doing this now — we’ve been shocked by videos of Black people being murdered by police. But we must remain motivated without another Black person being killed by racism. We must find a way to make anti-racism critical to our own humanity.

One, of several, ways I’m approaching this is through public writing, including at the New York Times. Each time I write about racism it’s a big effort. I have to face my fears about miscommunicating or being misunderstood. It’s important to push through those fears. With each piece I’ve received feedback — solicited and not — about how I can make improvements. This is challenging to hear when you’ve tried so hard! But this is also part of the necessary work — to listen, to hear, to accept the challenge, and, most importantly, to not walk away.

August 13, 2020

Deaths of Despair and Decreased Life Expectancy in the US

In recent years, life expectancy in the US has dropped, and deaths of despair have been a significant contributor. Drug overdoses and suicides have increased in tandem with the opioid crisis, and the outcome is shorter lives. In this second of four episodes on the current state of the crisis, we’ll talk about these tragic deaths and what we might do about them.

This updated series on the opioid crisis is supported by the National Institute of Healthcare Management.

Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers