Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 51

July 30, 2020

In Pursuit of Value-Based Drug Prices in the US: New York and Beyond

Despite overwhelming agreement among voters that the cost of prescription drugs is too high, Congress has yet to pass substantive legislation in recent years to tackle drug prices. In the absence of federal action, New York lawmakers stepped up to the task in 2017, establishing a drug spending cap in the state’s Medicaid program. Setting an annual limit on the state Medicaid program’s prescription drug spending, however, meant that the legislature also needed to give Medicaid officials a way to keep costs down. So how has New York gone about cutting excess drug spending?

The answer is that the New York legislature gave officials the power to systematically limit the price of high-cost prescription drugs to their therapeutic value.

More specifically, the state authorized its Medicaid Drug Utilization Review Board to conduct reviews of the value of expensive drugs when officials project that the program’s annual drug spending cap will be exceeded. After the board determines a value-based price for a drug, the state then negotiates additional rebates with the drug’s manufacturer.

To compel manufacturers to come to the table and concede supplemental rebates, the New York Medicaid program may implement a number of strategies intended to lower manufacturers’ profits if they don’t comply. These bargaining chips include instituting prior authorization requirements, directing Medicaid managed care organizations to remove the drug from their formularies, and limiting reimbursement for provider-administered therapies that are billed under the medical benefit. Under the terms of the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program, however, New York may not remove a drug from its Medicaid formulary. This means that using a state-run approval process, beneficiaries can still receive Medicaid coverage for drugs that are not on their managed care plan’s formulary.

Though the New York Medicaid program was the first public payer in the US to limit reimbursement for prescription drugs based on therapeutic value, this practice is common in many European countries. The New York Medicaid Drug Utilization Review Board utilizes many of the same tools used in health technology assessment in Europe, including quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and reference pricing, though in a more limited capacity.

To date, the New York Medicaid Drug Utilization Review Board has completed three pricing reviews. In these reviews, the board determined target supplemental rebate amounts for lumacaftor/ivacaftor (Orkambi), infliximab (Remicade), and nusinersen (Spinraza). Following the board’s reviews of lumacaftor/ivacaftor and infliximab, the New York Department of Health was able to reach confidential supplemental rebate agreements for both drugs with their respective manufacturers.

In the case of nusinersen, the board only recently announced the completion of their review at a public meeting on July 23, 2020. Though negotiations between New York officials and the drug’s manufacturer Biogen will be kept confidential, the state’s prospects for securing additional rebates seem promising in light of the drug’s billing under the medical benefit in Medicaid. This is the case because of the board’s ability to direct Medicaid managed care organizations to reduce reimbursement for provider-administered drugs billed under the medical benefit, which includes nusinersen, if manufacturers refuse to concede adequate supplemental rebates. It’s possible that this same leverage helped prompt Janssen Pharmaceuticals, the manufacturer of infliximab, to agree to pay additional rebates to New York after the board’s review of the drug last year.

Efforts to conduct assessments of the value of drugs and other medical goods and services in the public sector in the US have been met with fiery political opposition. After all, who could forget Sarah Palin’s infamous and wildly inaccurate claims about how the Affordable Care Act would create “death panels”?

More than a decade later, the consequences of rejecting cost-effectiveness research are starting to come into focus. Today, rising brand-name prescription drug prices (and increasingly-prevalent high-deductible health plans) pose a threat to Americans’ financial security and to the health of our communities. Political controversies notwithstanding, using cost-effectiveness research and analyses to pay for high-value prescription drugs can help US patients afford the drugs they need as prices continue to rise. While value is difficult to measure or even define in health care, working through those difficult questions is well worth the reward of maximizing patient health and lowering costs. Value-based pricing frameworks, such as those used by the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, are valuable tools that can help policymakers rationalize the way we pay for pharmaceuticals.

Taxpayer dollars have bankrolled the pharmaceutical industry’s inflated bottom line for far too long. To protect Americans’ health and financial security, lawmakers across the country should follow the trailblazing example of the New York Medicaid Drug Utilization Review Board and join in the pursuit of systematically-achieved, value-based drug prices in the US.

July 29, 2020

Not-so-shared cancer decision-making

In my cancer care so far, shared decision-making between doctor and patient is only half-working. In this post, I ask why.

Shared decision-making occurs in medicine when physicians help patients make choices that cohere with both the patient’s values and the best scientific evidence. In my previous cancer post, I described how I had to choose whether to be treated only with radiotherapy or to have radiation with concurrent chemotherapy. In choosing to have radiation-only — that is, no chemotherapy — I was helped by several physicians at the Ottawa Hospital. They answered my questions clearly and respectfully. Interestingly, my doctors disagreed about what I should do, and I was pleased that they were candid about that. Friends and family members in medicine also helped. I am particularly grateful to several physicians and cancer survivors, compassionate strangers who read my posts and wrote to me. Thanks to you all.

So when I think about these interactions, shared decision-making worked superbly for me. I will continue to say this even if the treatment fails because this aspect of the caregiving has been excellent, regardless of the (to-be-determined) outcome.

Except that none of these wonderful interactions matter if the health care system can’t process even simple communications from a patient.

On July 27, I got a call from the radiation clinic, telling me that my first radiation session would be on the 29th. Which is lovely, because I want to fry this tumour’s ass before it has further chance to spread. But a few minutes after I hung up, the chemotherapy clinic called to tell me about my first chemotherapy session.

Me: “Sorry, but I thought that I was clear that I had elected not to have chemotherapy.”

Clerk: “No, we have an order for you to start chemotherapy.”

Me: “Dr. X [the medical oncologist] asked me to decide about chemotherapy and let him know. I communicated that on MyChart.” [MyChart is the application that gives patients a (highly-restricted) view of Epic, the hospital’s electronic health record.]

Clerk: “You can’t use MyChart for that.” [The clerk was correct. MyChart, at least as implemented here, gives you no means to send a message to a doctor. I had misremembered.] “You have to use the Patient Support Line.” [That was what I had misremembered. I had used the Patient Support Line to get a message to Dr. X, not MyChart.]

Me: “OK, so can you cancel the appointment?”

Clerk: “No, you have to use the Patient Support Line.”

I hung up and called the Patient Support Line, which is a phone robot. When it answered, I recognized its voice, and I recalled that yes, I had called this line to send Dr. X my decision. You might imagine that the Patient Support Line would connect you to a person. Someone who can, you know, support you as a patient? Instead, it’s a barebones phone tree. The Patient Support Line allows you to leave a message, but it’s not clear to me who reads it or what they do with it. Regardless, I once again left my message for Dr. X. So far as I can tell, neither my first nor second message reached Dr. X or anyone who works for him.

Isn’t this box helpful?

Next, I opened MyChart, and yes, there are my chemotherapy appointments. OK, great, these are calendar appointments, so there ought to be some way to decline or cancel them, right? No, there is not. Well, then surely there will be a mechanism to mail the person who created the appointment to let them know it is incorrect. If there is, I can’t find it. There is a box that you can check to indicate that the information is correct, but there is no box to note that something is incorrect. The semantics here are puzzling. An unchecked box means either a) the patient ignored this or b) the patient thinks something is wrong. How is that helpful to anyone?

Stop, I tell myself. Don’t spend your time debugging an application for Ottawa Hospital’s IS Department. Let’s go old skool and telephone the Chemotherapy Program. I look up the number, call them, and tell the clerk my story.

Clerk: “This is New Patient Registration. This isn’t something we can handle. How did you get this number?”

Me: “It’s the number that’s listed? Anyway, whom should I call?”

Clerk: “That’s an excellent question. Please hold.”

He puts me on hold. A few minutes later, he returns to the call and — this is pure Canada — he is scrupulously polite with just the faintest hint of reproach that, somehow, I haven’t followed The Rules. But — again, pure Canada — he is helpful:

Clerk: “I’ve sent a message to Dr. X. A nurse will call you to discuss your concerns.”

I hang up, then realize that I forgot to ask whether that means that the appointment has been cancelled. Cynically, I predict that the next call I get from the chemotherapy office will ask me why I missed my appointment.

But I was wrong. A nurse calls within an hour.

Nurse: “What is your question is about your chemotherapy appointment?”

I tell my story again, and she promises to cancel the appointment. I think the problem is solved.

The loss of my time aside, I haven’t been harmed by this confusion. No one acted badly at any point, and busy people treated me with commendable patience. But measured against the aspirations of shared decision-making, this was a disaster. What’s the point of having a nuanced and sensitive discussion about values, probabilities, and uncertainty when it takes two weeks and multiple phone calls to communicate a simple “No, I do not want this treatment”?

I wasn’t harmed because I am a determined son of a bitch a medical school professor, meaning doctors pay me to tell them what they should think. So by personality and status, I don’t have any trouble raising my voice about my care. But I have someone I am close to, who I’ll call “Jim,” who would have been harmed. Jim is a former middle school teacher with a terrifying autoimmune disorder. He has limited mobility and experiences constant, severe pain. He’s frequently hospitalized and has had far too many surgeries. In my opinion, Jim’s care hasn’t been as good as it should be. But he’s not the kind of person who questions his doctors. If the system sent Jim incorrect chemotherapy appointments, he wouldn’t have interpreted it as system noise, as I did. He would have assumed that the doctor had changed her mind, and he would have sucked it up and done what he thought he was being told to do.

So, what’s the problem with shared decision-making? We imagine that medical care is something that a doctor provides to a patient. Consistent with that view, shared decision-making is presented as an ongoing conversation between a doctor and a patient. See, for example, Dr. Paul Kalanithi’s cancer memoir, in which ‘Emma,’ his empathetic and ‘best-in-world’ oncologist is there for him whenever he needs her. Unfortunately, these views of medical care and shared decision-making miss something important.

What they miss is that although doctor-patient dyads matter, patients are cared for by systems. Systems are sprawls of often loosely-connected people, linked by communications networks and institutional practices. Care processes must be structured so that doctors and patients can have conversations that facilitate shared decision-making. But that’s not enough. I need to be able to communicate my choices to the system. These choices should reach every relevant person in my care team. Finally, I should be able to monitor what’s happening and flag problems when care deviates from my understanding of the plan.

This requires (vastly) improved engineering of health information systems. It may also require us to rethink who does what when in the care process. For example, wasn’t the idea that primary care doctors were going to ‘quarterback’ the care process? What happened to that? These are challenging problems, and I don’t fault anyone. But there is so much work to do.

To read the Cancer Posts from the start, please begin here.

July 27, 2020

COVID-19 Update: July 25th Edition

The following is a new contribution to the Baker Institute’s Weekly Covid-19 Blog by Vivian Ho, Ph.D. (@healthecontx), James A. Baker III Institute Chair in Health Economics, Kirstin Matthews, Ph.D. (@stpolicy), Baker Institute Fellow in Science and Technology Policy and Heidi Russell, M.D., Ph.D., Associate Professor, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine and Associate Director, Center for Medical Ethics and Health Policy, Baylor College of Medicine.

By the Numbers

As of Friday, July 24, data from the Covid Tracking Project showed that the 7-day average (smoothed) number of new U.S. daily cases rose to 66,578, a 2% increase relative to 65,557 the previous Friday. The smoothed percent of cases testing positive fell to 8.4% from 8.7% one week earlier. The smoothed number of deaths in the U.S. rose 21%, from 726 a week earlier to 876 last Friday. Here in Texas, the growth in the number of smoothed daily cases fell 7% between July 17 and July 24, and the smoothed number of daily deaths increased from 174 to 196. The smoothed percent of people testing positive fell from 14.8% on July 17th to 11.2% last Friday.

Risk Factors and Disease Effects

Daily new coronavirus cases in the U.S. topped 65,000 as Europe’s number of new cases fell below 5,000. Experts attribute Europe’s success to social distancing and mask wearing, as well as more testing and better contact tracing. The United Arab Emirates tested over 40% of its population. Mass testing was so successful, that restaurants, cinemas, gyms, and beach resorts are operating almost normally.

A study of 59,073 contacts of 5,706 Covid-19 patients in South Korea that was summarized in The New York Times found that children younger than 10 transmit to others much less often than adults do, but the risk is not zero. And those between the ages of 10 and 19 can spread the virus just as much as adults do.

Starr County Memorial Hospital in south Texas has implemented an ethics committee and a triage committee to review all coronavirus patients as they come in to determine what treatment they would likely require and whether they would likely survive. Those deemed too fragile or sick or elderly will be advised to go home to loved ones.

The link between Covid-19 and hair loss is just starting to be reported and recognized in research.

Vaccines and Treatments

The U.S. government has pledged up to $1.2 billion toward the AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccine effort and secured a promise of 300 million doses by October. The U.S. also announced a $1.95 billion contract with Pfizer and BioNTech to secure 100 million doses of their vaccine by December (at $20 a dose), with the rights to acquire up to 500 million more.

During a House subcommittee hearing, officials from AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson said they would sell their vaccines at the cost of production, at least until the novel coronavirus pandemic subsides. Moderna Inc. and Merck & Co. executives said they would set prices exceeding their manufacturing costs.

Policy Interventions

President Trump urged Americans to wear masks for the first time last week.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted emergency use authorization for pooling samples from up to 4 patients for coronavirus testing in an effort to ease backlogs in testing.

Former FDA commissioner Scott Gottlieb explained that the White House ordered hospitals to report their COVID-19 patient data to the Department of Health and Human Services instead of the Centers for Disease Control, because CDC said that it was unable to report the age breakdowns for those being hospitalized for Covid-19 until the end of August. Dr. Gottlieb wrote that HHS is trying to re-create the data set using private contractors, a less than ideal strategy.

Landlords and property managers are pumping more outside air into their buildings in an effort to reduce the likelihood of building occupants catching the coronavirus. In addition to raising energy bills, the resulting higher emissions may trigger fines under some cities’ greenhouse-gas reduction regulations.

July 24, 2020

The Shifting Messaging on Masks

The messaging on masks amid Covid-19 has been mixed, and has shifted throughout the pandemic. As things have progressed, it has become clear that wearing a mask can help prevent the spread. We should be wearing masks when we go out in public, and that shouldn’t be a political statement.

July 20, 2020

Treating cancer: So many decisions

It’s July 16th, two weeks since the CT scan in the ED revealed the mass in my throat. Canadian medicine has rallied to my side. I have met with a throat surgeon, a radiation oncologist, and a medical oncologist. You know that you are in deep shit trouble when you need to talk to three subspecialists. It’s time to decide about my course of treatment. This post is about how I — or, better, my wife and I — made this decision.

First, let’s celebrate that the system recognized that it was my choice to decide what treatment I should receive. It wasn’t always so. Nineteenth- and early 20th-century doctors were white males who believed they had the authority to determine how patients would be treated. But starting in the 1960s, bioethicists insisted that this style of practice was inconsistent with respect for patients’ autonomy. Lawyers argued that, for example, removing a cancerous breast while a woman was anesthetized was an assault. That patients have rights to consent and that medical decision-making should be a collaboration between doctors and patients was a revolution — incomplete and imperfect — but much to the benefit of patients.

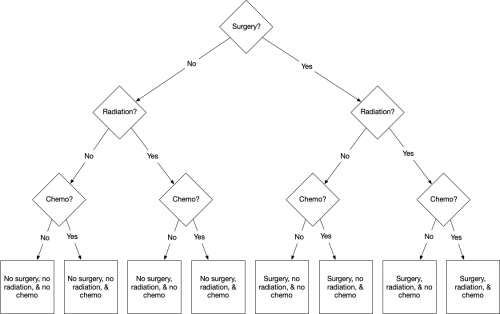

What are the choices for treating my cancer? In essentials, they are a) surgery (hence, the throat surgeon), radiation (the radiation oncologist), and chemotherapy (the medical oncologist). I can have all or none of these therapies, so there are 8 options, as you see below.

All possible treatment combinations.

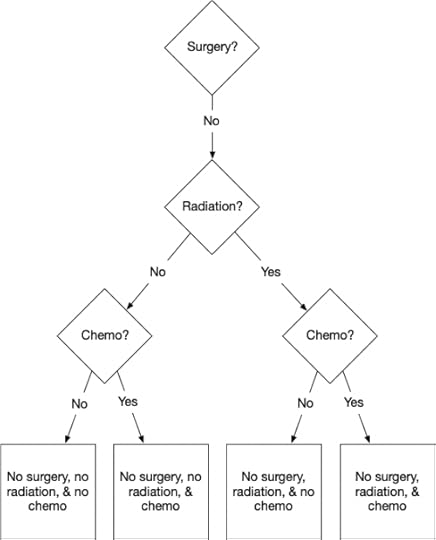

To my surprise, however, not even the throat surgeon thought that surgery was a good choice. Yes, it would get the carcinoma out of my throat, but so would a few grams of plastic explosive. A surgeon would have to excise significant portions of my throat and tongue. So if we take the ‘No’ branch, then the choices look like this.

Ruling out surgery makes things simpler.

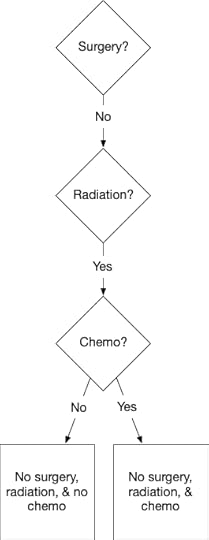

But the next choice is also easy. We must get the tumour out somehow, or it will kill me, and radiation will do that with less trauma than surgery. Radiation disrupts the functioning of the cellular nuclei, killing the cells. Because they are reproducing more quickly, cancerous cells have more active nuclei than healthy cells, and this makes them more vulnerable. This means that radiation is more likely to kill cancerous than healthy cells. So radiation can destroy the tumour while leaving the surrounding tissue injured but structurally intact.

The difficult choice is whether to have chemo.

This doesn’t mean that radiation is safe or comfortable. A standard part of the preparation for radiation is an exam from a dental surgeon. He explains that the treatment will kill my salivary glands, giving me a dry mouth. Saliva also prevents tooth decay. Therefore, to keep my teeth, I will have to practice an elaborate daily care routine for the rest of my life. Radiation will also weaken the bone in my jaw. So what? It beats certain death.

This leaves one more decision: should I have chemotherapy concurrently with my radiation treatment? Chemotherapy — in this case, a drug called cisplatin — is poison. However, it is more poisonous to cancerous cells than to healthy cells. As with radiation, the idea is to give you just enough to kill the cancer cells without killing too many of your healthy cells. Unlike radiation, however, chemotherapy will act throughout my body, not only on the mass in my throat.

This is a good thing because there is a chance that some cancerous cells may have seeded themselves in other organs of my body. If so, I may eventually have one or more new tumours. Randomized clinical trial data suggest that with radiation + chemo, I will have a higher chance of being alive in five years than with radiation alone. My doctors estimate that I have an 80% 5-year survival probability with radiation alone, and an 85% chance with radiation + chemotherapy. There’s uncertainty about these probabilities. Some of the data are old, and some were collected before the significance of HPV+ tumours was known. Nevertheless, I’m persuaded that radiation + chemo would give me a better chance of surviving.

But living longer isn’t the only thing I want. Radiation + chemo would be a more gruelling treatment than radiation alone. Worse, chemotherapy can cause permanent harmful side effects. The side effect I fear most is a chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairment (CICI, sometimes called ‘chemo brain’). There is emerging evidence that some (but not all) cancer survivors experience permanent deterioration of their abilities to remember things and solve problems. I am a researcher and writer, and being unable to continue my work would be a painful loss.

What’s the risk of CICI? Unfortunately, we don’t know because we have much less data on CICI than on cancer survival. For many reasons, cancer specialists have focused more on survival than long-term quality of life. My doctors say that they don’t see CICI in their patients, but is this because it doesn’t happen or because they did not follow-up with their patients to ask about it? My suspicion is that CICI is a bigger problem than most oncologists realize.

My preference, then, is to have radiation without concurrent chemotherapy. I’ll accept a small reduction in 5-year survival probability for a possible, but unquantifiable improvement in the chance that I will retain my mental acuity post-cancer treatment.

But am I thinking about this problem the right way? Medical decision making is always framed in terms of the interests and beliefs of an isolated patient. But I am more than just me. I have a spouse, and I’m a parent of 5 children (albeit now grown adults). Trading off a survival risk for a possibly better quality of life seems best to me, but one of my mantras is, “It’s not about you.”

Kathi and I talk about this at length. Her view is that if she had cancer, she’d do everything possible to be sure to be rid of it. “If it was in my body, I wouldn’t be able to think about anything else. But that’s not you at all.” She’s right. Even having seen the tumour, I think about it only when I get a twinge of pain in that region. It’s just another hassle, not something I’m anxious about. I ask, “If I don’t take the maximum treatment, won’t you constantly worry that it is still in me?” “You might think so, but I don’t think I will. And I know how much you would regret it if you could no longer write.” So, we’ll go with radiation only.

To read the Cancer Posts from the start, please begin here. The previous post, about the epidemiology of my cancer, is here.

COVID-19 Update: July 20th Edition

The following is a new contribution to the Baker Institute’s Weekly Covid-19 Blog by Vivian Ho, Ph.D. (@healthecontx), James A. Baker III Institute Chair in Health Economics, Kirstin Matthews, Ph.D. (@stpolicy), Baker Institute Fellow in Science and Technology Policy and Heidi Russell, M.D., Ph.D., Associate Professor, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine and Associate Director, Center for Medical Ethics and Health Policy, Baylor College of Medicine.

By the Numbers

As of Friday, July 17, data from the Covid Tracking Project showed that the 7-day average (smoothed) number of new U.S. daily cases rose to 65,557, a 20% increase relative to 54,561 the previous Friday. The smoothed percent of cases testing positive rose to 8.7% from 8.3% one week earlier. The smoothed number of deaths in the U.S. rose 11%, from 854 a week earlier to 951 last Friday. Here in Texas, the growth in the number of smoothed daily cases rose 16% between July 10 and July 17, and the smoothed number of daily deaths increased from 63 to 103. The smoothed percent of people testing positive rose from 12.9% on July 10th to 14.8% last Friday.

Risk Factors and Disease Effects

The number of daily coronavirus tests being conducted in the United States is only 35 percent of the level considered necessary to mitigate the spread of the virus. Harvard researchers say that at minimum there should be enough daily capacity to test anyone who has flu-like symptoms and an additional 10 people for any symptomatic person who tests positive for the virus.

A report by a distinguished panel of experts assembled by the Rockefeller Foundation, which included former FDA commissioners, recommends an additional $75 billion in federal funds to cover the additional costs of testing and tracing as well as to incentivize test development and production. The report contains detailed strategies for boosting testing to get the economy back on track.

An editorial in the New York Times promotes the adoption of faster, cheaper, though less accurate coronavirus testing based on saliva and paper-based test strips. The strategy is explained in more detail on a TWIV podcast and involves widespread daily testing for workers and school children using these $1 tests that provide results within minutes.

A Wall Street Journal article on the risks of flying cites an analysis by Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor Arnold Barnett based on current Covid-19 prevalence in the U.S. When all coach seats are full on a US jet aircraft, the risk of contracting Covid-19 from a nearby passenger is about 1 in 4,300 as of early July 2020. Under the “middle seat empty” policy, that risk falls to about 1 in 7,700.

Vaccines and Treatments

The first COVID-19 vaccine tested in the U.S. revved up people’s immune systems just the way scientists had hoped, and the shots are poised to begin key final testing. Findings on the first 45 volunteers were reported in the New England Journal of Medicine. A 30,000-person study to prove if the shots protect against the coronavirus may begin July 27th.

Two coronavirus drug and treatment trackers list the 20-most-talked about treatments for Covid-19 and describes the evidence underlying their current use or potential for future use as well as the state of vaccine trials.

Hospitals across the country are stocking up on drugs for treating Covid-19, hoping to avoid another scramble for critical medications should a second wave of the virus hit them. About 90% of hospitals and health systems are building safety stocks of about 20 critical medications, including those for patients on mechanical ventilation. However, hospitals from Houston to Miami are running short of remdesivir.

Policy Interventions

The United States could get the coronavirus pandemic under control in one to two months if every American wore a mask, said CDC director Dr. Robert Redfield last Tuesday.

Scientists have been looking at international models to determine how and when to open schools, if masks should be required, what do if someone test positive. Unfortunately, with limited data most answers are still unknown.

The US National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine released a report this week which promotes re-opening school, but specifically focused on K-5 grades and students with special needs. Previously the American Pediatrics Association also recommended re-opening schools, but backed down on their recommendation after pushback because of recent outbreaks of Covid-19 across the country.

As universities plan for fall terms, the NCAA updated its guidance for collegiate sports to mandate testing and isolation practices. Some conferences have cancelled their fall athletics. Others, particularly those generating the most revenue for their colleges, have limited their games.

As business leaders and health experts debate when to reopen national borders, an emerging spaghetti bowl of travel regulations will likely act as a brake on the global economic recovery for a long time. As much as $5.5 trillion of the global economy and nearly 200 million jobs related to travel are at risk from the curbs. Manufacturing and other sectors face steep losses as well.

July 17, 2020

Are Swimming Pools Safe? Are we worried about a second wave? COVID-19 Questions and Answers

Aaron Carroll answers more of your Covid19 questions. Click on a time code in the video description to jump to a specific question.

July 15, 2020

Why Health Experts Give Contradictory Advice

The following is a guest post from Jian Gao, PhD, Director of Analytical Methodologies, Office of Productivity, Efficiency and Staffing (OPES), Department of Veterans Affairs.

For decades we were admonished that saturated fat was not good for our health, but now we are told sugar rather than fat is the culprit. One day, moderate alcohol consumption is touted as wholesome, but on the next, any amount is deemed detrimental. Drinking coffee was once found causing pancreatic cancer but today it is not a problem. Now in real time, experts are battling over the choice of CABG or angioplasty for patients with coronary heart diseases. And most recently, you for sure have seen the headlines surrounding the controversies of COVID-19 treatments.

The irony is that these recommendations are all backed up by “solid” evidence, i.e., research findings. Why are research findings so often inconsistent and even contradictory? Of course, it is multifactorial (e.g., confounders in observational studies and small sample sizes in controlled trials). But one common factor standing out is the misunderstanding of p-values.

In research, the p-value is a practical tool that helps to guard against being fooled by randomness. It gauges the “strength of evidence” against the null hypothesis (a treatment does not work or is ineffective). For example, a p-value of 0.01 indicates the treatment is more likely to work than the one with a p-value of 0.05; however, by design, it cannot tell by how much – there is no basis to infer that the former is five times more likely to work than the latter or vice versa. Unfortunately, the p-value has been widely misinterpreted as the probability that a treatment does not work or a finding is by chance. As a result, the p-value has become the sine qua non for deciding if a study finding is real or by chance, a paper will be accepted or rejected, a grant will be funded or declined, a treatment is effective or harmful, or if a drug will be approved or denied by the FDA.

Of course, a “good” p-value has since turned into a “bad” magic number that researchers chase after. And worse yet, p-hacking has become a commonplace – just like what Andrew Vickers described:

It was just before an early morning meeting, and I was really trying to get the bagels, but I couldn’t help overhearing a conversation between one of my statistical colleagues and a surgeon.

Statistician: “Oh, so you have already calculated the P values?”

Surgeon: “Yes, I used multinomial logistic regression.”

Statistician: “Really? How did you come up with that?”

Surgeon: “Well, I tried each analysis on the SPSS drop-down menus, and that was the one that gave the smallest P value.”

Let alone the selective reporting of research findings with low p-values, most are unaware that the p-value, even if calculated legitimately, is not the probability a treatment does not work. For a p-value of 0.05, the chance a treatment (e.g., reducing dietary fat intake) does not work is not 5%; rather, it is at least 28.9% as elucidated in a recently published article. Given the p-value has been used for 100 years, why are the misunderstanding and misuse of p-values still rampant? Well, the answer lies in the Qs and As posted by George Cobb on the American Statistical Association (ASA) discussion forum:

Q: Why do so many colleges and grad schools teach p = 0.05?

A: Because that’s still what the scientific community and journal editors use.

Q: Why do so many people still use p = 0.05?

A: Because that’s what they were taught in college or grad school.

Regardless, our statistical education in schools falls short: how many students understand the subtle yet fundamental differences between significance and hypothesis testing after taking statistics courses? Most otherwise great statistics textbooks pay too little attention to these fundamentals. On the other hand, few medical journals are willing to see reduced submissions of manuscripts as a result of changing the use of p-values that the established investigators are used to.

Since the publication of the p-value statement by the American Statistical Association in 2016, more and more statisticians and scientists have become aware of the p-value fallacy. Unfortunately, little change has been seen so far in the medical field. It appears that only talking about the p-value is not the chance of a research finding being a fluke can hardly get anywhere. When seeing p-values, users inevitably fall back to the probability a treatment will not work unless they understand how vastly different they are.

In short, the misunderstanding of p-values spells disaster – for a p-value of 0.05, rather than one in 20 as commonly believed, nearly one in three or more research findings are flukes. Now, you can see why there is so much contradictory health advice from experts.

What is the fix? Well, like treating any maladies, we ought to work on the root causes: It is time to back to school. The difference between the p-value and the probability a treatment does not work needs to be taught in the classrooms. Students, researchers, and clinicians need to clearly understand what p-values are and what they are not. And that is not enough — without knowing the probability that a given treatment will or will not work, researchers and clinicians fly blind.

Thanks to James Berger and colleagues’ groundbreaking work, the calibrated p-value was established to inform us the probability that a treatment does not work or a research finding is a fluke. Based on the calibrated p-values, for example, for p-values of 0.1, 0.05, and 0.01, the chances a treatment does not work are at least 38.5%, 28.9%, and 11.1%, respectively, which are strikingly different from what commonly believed: 10%, 5%, and 1%.

Taken together, there is no reason for schools not to teach and medical journals not to use the calibrated p-values, given they are informative and easy to calculate.

For further reading on this topic, a recently published article endeavored to put all the loose ends together.

What’s Missing in the Effort to Stop Maternal Deaths

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2020, The New York Times Company). It also appeared on page B3 of the NYT print edition on July 14, 2020.

According to the best data available, as summarized in a report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the United States could prevent two-thirds of maternal deaths during or within a year of pregnancy.

Policies and practices to do so are well understood; we just haven’t employed them.

A first step is measuring maternal death rates, which is harder than you might think. The death needs to be directly related to the pregnancy or management of it, and confirming this requires careful data collection and assessment. Here’s a straightforward example: A death because of inadequate care during delivery would count as a maternal death, and one because of a car accident after delivery would not.

But there are trickier cases.

Early this year, the C.D.C. reported that in 2018, for every 100,000 live births, there were 17.4 maternal deaths. But this figure does not include maternal deaths from drug overdoses or suicide, so it may be an undercount.

Differences across groups

One statistic that we can be more certain of: There are large maternal mortality differences across racial and ethnic groups. The latest figures from the C.D.C. indicate that for Black women, the maternal mortality rate is 37.1 deaths per 100,000 live births. It’s less than half that, 14.7, for white women and less than one-third that, 11.8, for Hispanic women. There are also differences by region, with new mothers in rural areas facing greater threats to health than those in urban ones.

The best source of maternal mortality data comes from maternal mortality review committees, which now operate in all but a few states. They conduct case reviews to assess causes of maternal deaths.

When the C.D.C. pulled together data from 14 such committees, spanning 2008-17, it also found wide variation in death rates by race and ethnicity. For example, although non-Hispanic white women make up about two-thirds of the U.S. female population, they account for only about half of maternal deaths. Non-Hispanic Black women, on the other hand, make up about 12 percent of that population but account for nearly 40 percent of maternal deaths.

The racial differences in maternal mortality are paralleled in racial differences in infant mortality. At 11.4 per 1,000 live births, the Black infant mortality rate is more than twice that of the white infant mortality rate, 4.9.

The racial differences seen in both maternal and infant mortality are driven by the same forces. Relative to white people, Black Americans have less access to the health system and receive poorer care, with worse outcomes. This has been documented both broadly and specifically for birth outcomes. Racism, including in its institutional and implicit forms, underlies all these factors.

Another way racism plays a role is before pregnancy. “People of color experience the cumulative effects of disadvantages throughout their lives,” said Rachel Hardeman, an assistant professor with the University of Minnesota School of Public Health. “The constant stress of racism may lead to premature biological aging and poor health outcomes for African- Americans. This means they might enter into pregnancy less healthy.”

Medicaid’s role

One-third of pregnancy-related mortality occurs after delivery. Lack of insurance imposes a financial barrier to postpartum care that might have prevented many of these deaths. In all states, low-income pregnant women — those with incomes below 133 percent of the federal poverty level, though most states have higher thresholds than 133 percent — are eligible for Medicaid, which finances over 40 percent of births nationally.

But a couple of months after delivery, new mothers can lose coverage, particularly in states that haven’t expanded the program. Among states that had not expanded Medicaid as of June 2018, the median threshold for eligibility for Medicaid as a parent was 43 percent of the federal poverty level. Texas and Alabama had the least generous parental Medicaid coverage, at 17 percent and 18 percent. Women of color are more likely than white women to be covered by Medicaid, so are more likely to be affected by postpartum eligibility changes.

Before the Affordable Care Act’s coverage expansion, 55 percent of women enrolled in Medicaid at the time of delivery experienced at least one month without insurance during the six months after delivery. Nowadays there is a big postpartum coverage difference depending on which state people live in. States that did not expand Medicaid have three times the postpartum uninsured rate of states that have expanded the program (22 percent vs. 7 percent).

“Medicaid has a positive impact on the health of low-income women, but for many, eligibility is limited to pregnancy and the immediate postpartum period,” said Sarah Gordon, an assistant professor at the Boston University School of Public Health who studies Medicaid policy. “The program could be even more powerful in alleviating racial disparities if coverage was longer term.”

In a study this year in Health Affairs, she and colleagues documented a connection between postpartum Medicaid coverage and care. The study found that in Colorado, which expanded Medicaid in 2014, mothers retained Medicaid coverage for longer and used more postpartum outpatient care compared with mothers in Utah, which did not expand Medicaid until after the study was conducted. Other work shows that expanded Medicaid is associated with a drop in infant mortality rates, echoing findings from earlier Medicaid expansions for pregnant women.

Coverage and care after delivery isn’t the only way to reduce maternal and infant mortality. Coverage and care before pregnancy and during the prenatal period certainly matter, too, as does the kind of care received during delivery. For example, a systematic review found that continuous, personal support during delivery can improve maternal and infant outcomes, including reducing the likelihood of a cesarean delivery.

Though the statistics may not be perfect, America’s maternal mortality rate is higher than it need be and disproportionately so for Black Americans and those in rural areas. The evidence suggests that targeted public health investments and policy changes like expanding Medicaid coverage could help.

July 13, 2020

COVID-19 Update: July 10th Edition

The following originally appeared on the Baker Institute Blog and is coauthored by Vivian Ho, Ph.D. (@healthecontx), James A. Baker III Institute Chair in Health Economics, Kirstin Matthews, Ph.D. (@stpolicy), Baker Institute Fellow in Science and Technology Policy and Heidi Russell, M.D., Ph.D., Associate Professor, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine and Associate Director, Center for Medical Ethics and Health Policy, Baylor College of Medicine.

By the Numbers

As of Friday, July 10, data from the Covid Tracking Project showed that the 7-day average (smoothed) number of new U.S. daily cases rose to 54,561, a 15% increase relative to 47,244 the previous Friday. The percent of cases testing positive rose to 8.4% from 7.4% one week earlier. The smoothed number of deaths in the U.S. rose 16%, from 529 a week earlier to 614 last Friday. Here in Texas, the growth in the number of smoothed daily cases rose 20% between July 3 and July 10, and the smoothed number of daily deaths increased from 36 to 63. The percent of people testing positive rose from 12.7% on July 3rd to 12.9% last Friday.

Risk Factors and Disease Effects

We are six months into the pandemic, and scientists still face multiple unresolved questions including: why people respond differently; is immunity achievable and how long will it last; is the virus developing worrisome mutations; how well will vaccines work; and where did the virus originate from.

Two distinct strains of SARS-CoV-2 are recognized – the D variant that originated in Wuhan and a G variant. International tracking reported in Cell reveals that the newer G variant is currently the dominant strain in the US and is more infective. A video depiction of spread by strain is viewable online.

More than 650 coronavirus cases have been linked to nearly 40 churches and religious events across the United States since the beginning of the pandemic, with many of them occurring over the last month.

The personal protective gear that was in dangerously short supply during the early weeks of the coronavirus crisis in the U.S. is running low again as the virus resumes its rapid spread and the number of hospitalized patients climbs. Test shortages are also pervasive.

After an international group of 239 experts called on the World Health Organization to review the research on airborne transmission of the coronavirus, the W.H.O. finally acknowledged that the virus can linger in the air in crowded indoor spaces, spreading from one person to the next.

Vaccines and Treatments

So many coronavirus vaccines are nearing the pivotal testing phase, that researchers and companies are going to extraordinary lengths to recruit the tens of thousands of healthy volunteers needed for testing. Volunteers can sign up here.

An editorial co-authored by former FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb explains how antibody drugs that potentially could protect the elderly and the immune-compromised for months could be ready for use as early as this fall. However, the federal government must invest substantial funds to enable drug makers to ready these drugs for mass-production.

Policy Interventions

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will not revise its guidelines for reopening schools despite calls from President Donald Trump and the White House to do so, agency Director Dr. Robert Redfield said Thursday. The president tweeted that the guidelines were “very tough” and “expensive,” while in another tweet threatened to cut off school funding if schools resisted opening.

Sweden, which never locked down during the pandemic, has suffered higher Covid-19 deaths per capita than other developed countries, and reaped no economic benefit from keeping their economy open.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response is the top U.S. agency charged with preparing for a pandemic and overseeing the medical stockpile. ASPR had a $2.6 billion budget for fiscal 2020 and prioritized preparation for a possible bioweapon, chemical, or nuclear attack, and did little to prepare for a pandemic.

Young people in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, hometown of the University of Alabama, were reported to be throwing Covid-19 parties, where people who have coronavirus attend and the first person to get infected receives a payout, local officials said. Meanwhile, Tulane University warned students of suspensions or expulsions if they are found to have hosted parties or gatherings of more than 15 people.

The Texas Medical Board emailed members this week to remind them of emergency medical licensure changes making it easier for out-of-state or retired practitioners to practice in Texas. With the rise in Covid-19 patients in Texas, these providers are badly needed.

Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers