Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 48

October 2, 2020

Radiation therapy for cancer: DONE

In my last post, I described what radiation therapy for oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma is like. In brief: The purpose of radiation is to destroy my tumour while just-about-but-not-quite killing the healthy tissue surrounding it. As I described, I’ve had severe throat pain, including great difficulty swallowing. As a consequence, I’ve lost 30 pounds.

So, early in September, I had a nasogastric (NG) feeding tube inserted.

My NG tube. I have tucked the end that connects to the feeding bag under my shirt.

This allowed me to put units of concentrated nutritional products — I won’t dignify them with the term ‘food’ — into a bag on an IV pole. I dilute the product with water and, in the morning, with brewed coffee. The bag drips the product into my NG tube, which carries it into my nose, through my sinuses, past my inflamed throat, and empties directly in my stomach. The tube was moderately painful to insert, and you spend much of your day tethered to an IV pole. But it solved my dehydration and halted my weight loss, so it’s a win.

The great news is that I finished the last of my 35 radiation treatments on September 18th. The rigours of therapy aren’t over: my throat’s inflammation grew more acute in the week following the end of treatment, the way a sunburn can feel worse the next day. Nevertheless, I’m sleeping better, and my energy has improved.

A consultation with my home health care aide, Mika the Alaskan Shepherd.

Or so things stood, until this weekend. On Sunday, Mika — my 5 & 1/2-month-old King Shepherd/Malamute mix — careened into my lap while I was working on the couch. She weighs 24 kg — 50 freaking lbs — and she hip-checked my feeding tube, which yanked it out. Home health care is an adventure. Luckily, I am already sufficiently recovered that I can drink my coffee and Ensure cocktails, more or less, so we haven’t reinserted it.

cocktails, more or less, so we haven’t reinserted it.

Otherwise, I’m sleeping late, and after I get up, I mostly nap. Oropharyngeal cancer survivors tell me that this will continue for weeks. I won’t be scanned again for a few months, so I don’t know whether the treatment worked. I’m just grateful that it’s over.

I deeply appreciate all the messages of support, particularly from fellow cancer patients. Please keep reading for just a couple more posts. I want to reflect on how cancer changed me, psychologically and spiritually. And I will do one final post about how the COVID epidemic has affected the health care system, as seen by a cancer patient.

To read the Cancer Posts from the start, please begin here.

The post Radiation therapy for cancer: DONE first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

October 1, 2020

The Immune System, T-Cells, and Covid-19

So far we’ve been pretty focused on the antibody side of things during the pandemic, but recent work suggests that T Cells aren’t sitting this one out, and that could mean something significant in terms of immunity, even for people who haven’t been infected with the new coronavirus.

The post The Immune System, T-Cells, and Covid-19 first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

September 28, 2020

The Supreme Court, the ACA, and COVID-19 Walk into a Bar

As countless news stories have now described, Justice Ginsburg’s death and her likely replacement by Judge Amy Coney Barrett have raised the odds that the Supreme Court will hold invalid all or part of the Affordable Care Act. In the New York Times last week, Andy Slavitt and I discussed what that should mean for the coming election:

Republicans don’t want to talk about health care in this election. The topic typically ranks as the single most important issue for voters, who view Democrats more favorably on it. Indeed, Republican losses in the 2018 midterms were widely attributed to the party’s stance on health reform.

But President Trump’s support for a dangerous Supreme Court case offers a simple, clear way to explain to voters that Republicans are lying when they say they support protections for people with pre-existing conditions. The explanation will land with particular force in a country suffering from a botched response to the coronavirus pandemic.

Keeping health care in the news will also focus attention on all the other ways that the Trump administration has worked to make Americans feel less secure: imposing onerous paperwork requirements on Medicaid beneficiaries; crippling the health care exchanges; and sowing discord in the insurance markets. The percentage of Americans without health insurance has ticked up every year since President Trump took office.

The details are complicated. But the Supreme Court case is mercifully easy to grasp. The lawsuit poses an existential threat to the nation’s health care system, and President Trump should be judged for recklessly supporting it.

If you’re playing the odds, the case is still probably a loser. The Chief Justice has twice rejected much stronger challenges to the law and Justice Kavanaugh may supply the fifth vote to turn the case away. Kavanaugh is a standing hawk and the plaintiffs, as I’ve argued, don’t have standing. He has written recently of the importance of salvaging as much of a congressional statute as possible, even when it contains a constitutional flaw. And when the first Obamacare case came before him when he sat on the D.C. Circuit, then-Judge Kavanaugh stayed his hand and voted to dismiss the case on jurisdictional grounds.

But no justice’s vote is assured, and the ACA’s supporters are right to be nervous about the possibility of a calamitous outcome. In particular, Andy and I flagged a suggestion that Richard Primus and I made nearly two years ago: that Congress could pass a one-sentence law that would make the case evaporate. As Andy and I explained, “Democrats could put all of this nonsense to an end — but only if they win big in the election.”

I also had the chance to go on Andy’s podcast, In the Bubble, to discuss the whole mess. (I stole the headline for this blog from the show’s producer.) I’m probably Andy’s least illustrious guest—he’s interviewed Governor Gretchen Whitmer, Andrew Yang, two former FDA administrators, and the science writer extraordinaire Ed Yong—but I tried to keep up. As I told to Andy, adding Judge Barrett to the Supreme Court means there’s a bigger margin for crazy. “If you had Judge Barrett on the court” back in 2012, I told him, “the ACA would be gone already.”

I also spent last Thursday grousing on twitter about President Trump’s latest stunt of trying to use an executive order to claim that he’s protecting people with preexisting conditions. No, I explained, “calling something an executive order does not make it law.” Instead, issuing the executive reflects a presidential effort to confuse the American public about the extraordinarily high stakes of the coming election.

The post The Supreme Court, the ACA, and COVID-19 Walk into a Bar first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

How other countries balance drug prices and innovation (part 1)

This is the first of two posts reviewing how countries around the world factor patient access and innovation into prescription drug pricing. A subsequent article will address how France and England navigate these issues.

The idea that patients in the US shouldn’t pay more for prescription drugs than patients in comparable countries around the world has broad-based political appeal. That’s why lawmakers on both sides of the aisle have proposed legislation to base what Medicare pays for drugs on prices in other countries with comparable GDPs and make it easier to import drugs from Canada. But before we put US drug pricing levels at least partly in the hands of non-US policymakers, it’s worth taking a look at how other countries approach drug pricing and how much emphasis their policymakers place on the competing priorities of patient access to drugs (which is facilitated by lower prices) and drug innovation (which is facilitated by higher prices). This post reviews how Germany and Canada factor access and innovation into prescription drug pricing.

Germany: Product Reference Pricing with an Eye for Innovation

In Germany, the passage of the 2011 Pharmaceutical Market Restructuring Act established two goals as paramount in the country’s approach to drug pricing: maximizing patient access to high-quality prescription drugs and establishing durable pharmaceutical market incentives that ensure high-value innovation. This 2011 reform, known as Arzneimittelmarkt-Neuordnungsgesetz or AMNOG, established a process in which an independent research nonprofit and a federal regulatory agency jointly evaluate the clinical benefits of new drugs after the European Medicines Agency grants those drugs marketing approval.

For each new drug, this joint body of researchers and regulators use a strategy known as product reference pricing to compare a product’s indication-specific benefits with existing therapies and assign the new drug’s comparative benefits to one of six categories: “major added benefit; considerable added benefit; minor added benefit; nonquantifiable added benefit; no evidence of added benefit; and less benefit than the appropriate comparator(s).” During the first year that the drug is on the market, the manufacturer can set the price at any level it chooses.

Following this assessment of a drug’s therapeutic benefits, drug manufacturers initiate pricing negotiations with the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Funds, an organization representing German health insurance payers that cover more than 90% of the population. In these pricing talks, statutory insurers use reference pricing to set upper bounds on reimbursement. If the statutory payers and manufacturers fail to reach an agreement on a fair reimbursement level, the dispute is sent to an arbitration board that sets a price. Manufacturers may elect to opt-out of this process at various junctures to avoid conceding a low price that would be listed in the official German drug price list, which could compromise the company’s profits in a number of other countries that partially base reimbursement levels on prices paid by German insurers. However, manufacturers that opt-out of this process must exit the German market.

All things considered, the 2011 AMNOG reforms restructured the German approach to drug pricing with an eye for both innovation and access. The explicit focus of the German model on upholding both patient access and incentives for innovation is a notable and important example of how policymakers can balance these competing priorities. Though drug research and development is a notoriously long process, early research indicates that the 2011 reforms seem to have effectively upheld both innovation and access thus far.

Canada: Emphasizing Access

In Canada, outpatient drug benefits are not included in Medicare, the country’s health care financing system that is primarily administered and funded by provincial and territorial governments. As a result, roughly two-thirds of Canadians purchase private drug coverage individually or through their employer, though the Canadian government provides drug coverage to certain populations under certain circumstances. (Note: this post does not address the distinct structure of drug pricing and assessment in Quebec. Unlike the rest of the Canadian provinces and territories, Quebec conducts its own health technology assessments and reimbursement negotiations.)

Much like in the US, the formulary placement process in Canada begins after federal regulators grant marketing approval to new drugs. After new drugs are approved, an independent, federally-funded, not-for-profit health technology assessment organization, the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH), evaluates the clinical and economic value of those drugs. With the exception of Quebec, CADTH advises publicly-funded drug plans across the country on formulary decisions in regard to the clinical benefits and cost-effectiveness of both new and on-market drugs. CADTH’s reimbursement recommendations are not binding, however, so drug plans are ultimately free to make their own reimbursement decisions.

CADTH’s extensive resources and drug product reviews contain very few references to innovation, an indication that the organization does not view innovation as a primary consideration in its recommendations. Instead, CADTH’s focus seems to be on helping publicly-funded drug plans design well-evidenced and value-based formularies and reimbursement protocols.

Once CADTH issues a recommendation on how payers should reimburse a newly-approved drug, a conglomerate of publicly-funded drug plans known as the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance (pCPA) determines whether to enter into negotiations with a manufacturer. As a negotiating bloc with a substantial number of covered lives, the pCPA allows public drug plans to purchase drugs at lower prices than they would otherwise be able to secure. Like CADTH, the publicly-stated objectives of the pCPA do not include promoting innovation. Instead, the pCPA focuses on achieving lower prices and better access for patients.

As an independent and quasi-judicial federal body, the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) is responsible for regulating the prices of all patented drugs in Canada. The purview of the PMPRB includes non-prescription drugs but excludes non-patented prescription drugs like generics. Using pricing data that manufacturers submit biannually to the board, the PMPRB determines if drugs have been priced excessively. In making this determination, Canadian federal law stipulates that the PMPRB “shall not take into consideration research costs other than the Canadian portion of the world costs related to the research that led to the invention pertaining to that medicine or to the development and commercialization of that invention, calculated in proportion to the ratio of sales by the patentee in Canada of that medicine to total world sales.” Once the PMPRB makes a determination of excessive pricing, it may direct the manufacturer to reduce the drug’s price “to such level as the Board considers not to be excessive.”

The PMPRB’s inability to consider drug development costs incurred outside of Canada indicates that the Canadian government may not view incentivizing global drug innovation as its responsibility. From a self-interested standpoint, this arrangement makes sense: a disproportionate share of global pharmaceutical revenue comes from the United States, so the Canadian government has little incentive to keep manufacturers’ profits high to reward innovation. Rather, the Canadian government’s approach emphasizes managing drug prices. Though this may benefit Canadian patients, this strategy does little to promote the ongoing development of new prescription drugs.

Research for this piece was supported by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation.

The post How other countries balance drug prices and innovation (part 1) first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

September 18, 2020

COVID-19 Pandemic Leads to Decrease in Emergency Department Wait Times

For years, public health and medical professions have been worried about the impacts of long emergency department (ED) wait times. Emergency departments are routinely crowded, and the long wait before receiving care can have serious consequences on patient outcomes. As areas became impacted by COVID-19, ED visits plummeted, creating a new problem: patients forgoing emergency room care.

As COVID-19 hit, a mixture of public fear about EDs being hotbeds for the virus and solutions implemented by EDs to divert non-emergent patients in preparation for the pandemic seems to have decreased demand for emergency care. While many non-emergent patients seem to have stopped going to the ED, so did many urgent patients. Indicators of medical neglect, like cardiac death, began to rise. This, and other statistics like it, provide evidence that ED demand is, at least partially, driven by public perception.

For JAMA Health Forum, Austin Frakt and I delve into the reasons for this drop in acute care acquisition and discuss how to keep wait times manageable as the pandemic subsides. Check out the full article here!

Research for this piece was supported by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation.

The post COVID-19 Pandemic Leads to Decrease in Emergency Department Wait Times first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

September 17, 2020

Covid-19 and Long-term Recovery

Most of the world has been working on the assumption that when a person recovers from Covid-19, everything just goes back to normal. As the pandemic progresses though, we’re learning about some patients who experience long-term complications from the disease.

The post Covid-19 and Long-term Recovery first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

September 12, 2020

Why can’t we have nice(r) things? Google Nest Protect edition.

I’ve had Google Nest Protect smoke/CO detectors for about 10 months now. Here’s an update to my prior post about them and how they could be better.

When the story left off, I had noticed some annoyances upon initial installation and routine troubleshooting. What I didn’t write about is that after a few more weeks of struggle, the Nest techs (all very helpful) determined that three of my nine units (33%) were defective. So, they shipped me three new ones. Then, after a similar amount of struggle, they determined that one of the three new ones (33% again) was also defective, so they sent me one more.

A 33% defect rate is bad. Maybe Google Nest had a particularly bad run of production of the Protect devices and this is not the rate all the time. Or maybe I just got particularly unlucky and the true rate is lower … or maybe it’s higher! Who knows.

Anyway, after working through all that, the devices hummed along perfectly for nearly 10 months. I was happy and felt justified in switching from the annoying First Alert products I previously owned and detested.

Then, a few days ago, I got some warning signs of trouble. Some of my Nest Protect devices started complaining of being offline, disconnected form Wi-Fi (still functioning as detectors though). I followed guidance to put them back online, which seemed to work, but only briefly, if at all. Devices lost connection again.

After a good hour with tech support, we discovered that what my Nest devices needed was a software update, which can be manually forced. This is supposed to happen automatically (good) but somehow didn’t, at least for some of my devices (bad).

Here’s my first gripe: Nowhere in the help pages for a Nest Protect that won’t connect to the internet does it suggest to force a software update. The help pages are just not has helpful as they could be. Further, why are there help pages at all? In other words, why do I have to search for help online? Nest has an app. The app should (and does) notice when a device is offline or has any other problem. A better app would walk the user through troubleshooting steps.

Yes, that would require an investment in a better app. But it could allow Google Nest to redeploy its human techs to other things than explaining how to get a device back online.

Here’s my second gripe: After we got all my devices back into shape, the Nest Protect app didn’t update for over 24 hours. Devices themselves were working fine (as one can tell by pressing their buttons to get a report) and the Nest web browser page said all was well. But the app wouldn’t update, not after a reset or reinstall. The tech said it could be delayed by 30 minutes. It took a full day. That’s nuts.

Fundamentally, the Google Nest app, while good, is not great. This is typical of Google — fantastic out of the gate and then very little improvement, even in obvious areas about which numerous users have complained. Going from good to great is just not what they do, probably for sound business reasons (I guess) but still to the annoyance of users.

All in all, I’m still happy with Nest Protect. They’re still massively better than First Alert. Even when I’ve had issues, none of them woke me in the night. None of them set off blaring alarms, freaking out my kids. It’s good technology. But it could easily be even better.

The post Why can't we have nice(r) things? Google Nest Protect edition. first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

September 11, 2020

COVID-19 and Convalescent Plasma

The FDA recently issued an emergency use authorization for convalescent plasma to treat Covid-19. The idea is that plasma from a donor who has recovered from Covid-19 has antibodies that can help treat patients who are now in the early stages of infection. Does this work? Are there any downsides to this emergency approval? Let’s find out.

The post COVID-19 and Convalescent Plasma first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

September 8, 2020

Radiation therapy for cancer: Two weeks left

To remind you: I am undergoing radiation treatment for an oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. I have now completed 26 radiation sessions, and there are just 9 more to go. Treatment will end on Friday, September 18th. I am going to get through this, but it is not enjoyable. Here are some notes on what it has been like.

Radiation works by doing more damage to the tumour than to the healthy flesh that surrounds it. The tumour isn’t served by my nervous system, so even though it is dying and visibly shrinking, there’s no pain in the tumour itself.

However, the damage to the surrounding flesh is considerable. My wife (a physician) commented that with throat cancer, unlike with radiation of internal tissues, you can see the damage that the treatment does to the inside of your throat. “It’s absolutely shocking what your mouth looks like.” At first, I told friends that it was like having a severe sunburn on the inside of my throat. That inflammation was (and is) easily visible. For a while, I found it unpleasant but tolerable. More recently, blisters and ulcers have formed on my tongue, gums, in the soft tissues surrounding my tongue’s base, and on the hard palate above it.

The increased damage has made it painful for me to speak or to swallow. The radiation is also killing my salivary glands. There’s less saliva, and the saliva I have is viscous, clogging my mouth and throat. This limits the number of hours I can sleep continuously. My throat clogs, I get a coughing fit, and the coughing wakes me up. (And it hurts.) I then need to clear my throat, possibly take a pain pill, and read until I can go back to sleep.

I agreed — reluctantly — to take Dilaudid, a potent opioid analgesic. I am not taking the maximum dosage, which is lucky because everyone tells me that the pain will continue increasing for the next month. This has helped immensely. However, Dilaudid immediately reshaped my life around a 4-hour pill-taking cycle. I take a dose, wait some minutes for it to begin to work, use a flattened club soda rinse to clear the icky saliva, then rinse my mouth with a lidocaine mouthwash. The opioid and lidocaine make it possible to swallow and talk, at least for a while. Each cycle, I try to drink 16 oz of water and an Ensure, and perhaps eat a poached egg. Then I read, do some chores, try to work, maybe play Skyrim, or nap until it is time for the next pill.

The radiation also kills my tastebuds. (Curiously, COVID-19 also deprives some people of the ability to taste.) Water now tastes like highly dilute dishwashing soap, and everything else tastes worse. My nostrils, however, are sharp as ever. So while my nose tells me that I have delicious food on my plate, my mouth tells me that it is inedible.

My fettucini, in better days (2020-04-11).

Moreover, if I can’t taste I can’t cook. It’s insane to be upset about this: I also won’t be able to cook if cancer should kill me. But cooking is my only craft skill (well, besides R coding and expository English prose). My wife and I are cooked-family-dinner-every-night people, family-feast people, bread-and-wine-and-beer-and-friends people. We are restaurant people and food tourists. Preparing and serving food to others is work I do to sustain love.

Bucatini alla’amatriciana, local craft beer, green beans, friends. 2020-05-10.

People tell me that my ability to taste will — probably — mostly return. I surely hope so. Should you get oral cancer, I recommend the autobiography of Chef Grant Achatz, the creator of Alinea in Chicago. At the peak of his career, he developed my cancer, but unfortunately, it was diagnosed at Stage 4. He was expected to lose his tongue and even then was given only an even chance of surviving two years. Instead, he chose a radical treatment plan: chemotherapy, followed by 64 sessions of radiation, followed by a surgery that preserved most of his tongue. Chef Achatz has recovered his ability to taste.

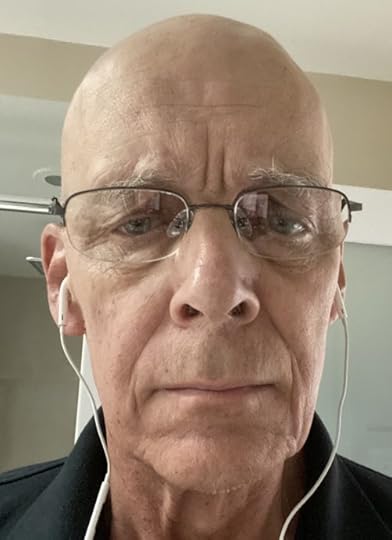

Me. 2020-09-07.

That’s all in a hypothetical future. Right now, it takes discipline just to eat. I have lost 20 lbs. Cancer — or its treatment — seems to induce anorexia. I’m clearly starving yet I have no appetite. Cancer has a look, a kind of grayness or weathering. I’m just starting to be able to see it. My wife says that I have had it for some time. My iPhone face recognition no longer recognizes me.

To read the Cancer Posts from the start, please begin here.

The post Radiation therapy for cancer: Two weeks left first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

The Disasters That Built the FDA and Where We Go From Here

The US Food and Drug Administration, as it exists today, was formed in reaction to public health disasters. The devastation wrought by elixir sulfanilamide, thalidomide, and the AIDS epidemic, among other tragic events, prompted popular outrage and demands for change; in turn, the public’s response to these tragedies helped establish a robust federal agency that evaluates the safety and efficacy of prescription drugs and high-risk medical devices before they are widely sold. To safeguard the integrity of the FDA and protect the health of people in this country for generations to come, we have a responsibility to ensure that the current pandemic reshapes the Food and Drug Administration for the better.

The Elixir Sulfanilamide Tragedy and the FDA’s Premarket Oversight of Drug Safety

Before public outrage erupted over the deaths of more than 100 people that were traced back to a new and untested drug, Congress was not able to pass proposed legislation to empower regulators to verify the safety of new pharmaceuticals. Supported by their lobbyists, manufacturers prevailed with their arguments that federal oversight of drug safety was “dangerous and un-American.” For more than five years after it was introduced in the Senate, the original bill that would become the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act received little attention from lawmakers.

It was only after the 1937 elixir sulfanilamide tragedy, in which a drug containing a poisonous solvent killed scores of people, that demands for reform prompted Congress to take action. In 1938, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt passed the landmark Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act into law, authorizing the FDA to test the safety of new pharmaceuticals before those products could be sold and marketed.

The Thalidomide Disaster and FDA’s Premarket Oversight of Efficacy and Manufacturing

Though the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act accorded the FDA some authority to monitor the safety of new drugs, the legislation had some major limitations; in particular, the agency still had no real power to ensure that new drugs were effective, it could not enforce safe manufacturing standards, and manufacturers could still sell new products without FDA approval after 60-180 days if the agency did not prevent such action.

Those flaws were made abundantly clear in the case of thalidomide, a drug intended by its manufacturer to be used by pregnant women to relieve nausea, but which instead vastly increased the risk of phocomelia, a birth defect. The drug was widely sold in Europe but had a muted effect in the US due to the heroic efforts of FDA scientist Frances Kelsey. The drug still caused some damage in the US because the drug’s manufacturer distributed thalidomide to physicians across the country as part of an unregulated “trial” while Dr. Kelsey did everything in her power to prevent full FDA authorization.

In response to this international incident and the public’s increased awareness of the risks of widespread use of drugs before adequate testing, Congress passed the Kefauver-Harris Amendment in 1962. This legislation required that manufacturers seek the FDA’s affirmative approval before new drug products are sold to the public, mandated that manufacturers demonstrate with substantial evidence the efficacy of new drugs prior to approval, and gave the agency the power to regulate manufacturing standards and facilitates, among other new powers.

HIV/AIDS, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, and Patient Communities’ Input at FDA

Facing a federal government that willfully ignored and trivialized the deaths of people with AIDS, the trailblazing activism of ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) demanded that government officials pay attention to an emerging national epidemic that threatened the health of gay people and others with AIDS. Activists went to heroic lengths to fight for more patient input in the FDA drug approval process, leading the FDA to formalize opportunities for expanded access to investigational drugs during clinical trials and to develop a number of expedited development programs for new drugs treating serious or life-threatening diseases.

AIDS activists’ protests and campaigns overcame discrimination, stigma, and blatant disregard for human life to leave a lasting imprint on the FDA. Their brave actions helped promote the role of patient voices and advocates in the drug development process.

Leaving It Better Than We Found It: The COVID-19 Pandemic’s Impact on the FDA

In the middle of a global pandemic that has taken hundreds of thousands of lives in this country, the FDA is facing the gravest crisis of faith in its history. The sitting president of the United States recently seemed to accuse “deep state” actors at the FDA of impeding the development of vaccines and therapeutics. In August, at a press conference organized to tout the administration’s achievements in addressing a pandemic that is killing thousands of Americans each day, Commissioner Stephen Hahn incorrectly overstated the potential benefits of convalescent plasma as a treatment for Covid-19 (the agency fired its recently-installed chief spokesperson afterward).

Perhaps most alarmingly, Commissioner Hahn has issued emergency use authorizations for Covid-19 treatments with virtually no evidence supporting them and appears willing to do the same for a Covid-19 vaccine candidate before Phase III trials are complete. This is hard to square with the commissioner’s prior commitment to sign off on widespread distribution of a Covid-19 vaccine only “once studies have demonstrated the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine.”

In spite of the damage that the last few months have done to the agency’s integrity, the novel coronavirus pandemic can still leave a positive legacy at the FDA. As I put it in a blog post in June, the FDA needs to get back to basics. Transparency, integrity, and rigorous evaluation of drug safety and efficacy are the bedrock of the FDA. Diverging from these tried-and-true principles, such as by issuing an emergency use authorization for a Covid-19 vaccine candidate without clear emerging evidence of its benefits outweighing its risks, would jeopardize both the public health and the public’s trust in the agency.

Research for this piece was supported by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation.

The post The Disasters That Built the FDA and Where We Go From Here first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers