Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 46

November 12, 2020

Does Supplemental Vitamin D Help Treat and/or Prevent Covid-19?

Ah, Vitamin D, back again. We’ve made our case on how unnecessary Vitamin D supplements are for outcomes like diabetes, cardiovascular and musculoskeletal health, and overall mortality. But what about its effect on viral infections like Covid-19? Can it reduce symptom severity, or perhaps even reduce your odds of becoming infected in the first place?

The post Does Supplemental Vitamin D Help Treat and/or Prevent Covid-19? first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

November 10, 2020

A Survey of Racial and Ethnic Disparities in COVID-19 Outcomes at State, Tribal, and County Levels

Allison R. Kolbe, Ph.D. is an Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Engineering Fellow at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Sean A. Klein, Ph.D. is a Presidential Management Fellow at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation.

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in over 6 million infections and more than 200,000 deaths in the U.S. alone, and has exposed long-standing health disparities through its disproportionate impact on racial and ethnic minority communities. These disparities are likely due to a complex combination of risk factors, such as the presence of comorbidities, discrimination, healthcare access and utilization, occupation, or other social determinants of health. As the pandemic continues, understanding the presence and extent of this disproportionate impact remains an area of active and ongoing research. Here, we provide a current snapshot of COVID-19 case and mortality demographic data at state and, where available, tribal and county levels with a focus on identifying and quantifying racial disparities. A more detailed report is available here.

Data availability and limitations of demographic data for COVID-19 outcomes

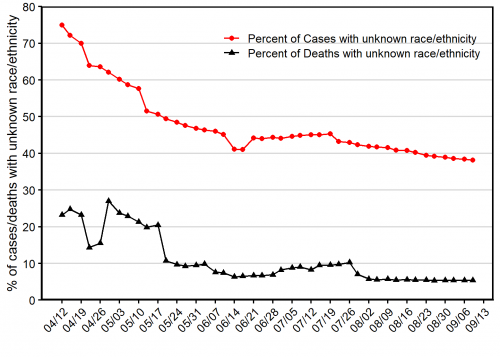

An important first step to understanding whether and where disparities in COVID-19 outcomes exist is understanding the available data. Data reporting on the racial/ethnic demographics of COVID-19 cases and deaths has improved significantly since the early months of the pandemic (Exhibit 1).

As of September 9, 2020, all 50 states and the District of Columbia were reporting data on COVID-19 infections and/or deaths by race and/or ethnicity. While the number of states reporting race and ethnicity demographics for COVID-19 cases and deaths has improved significantly since April, about 38% of all COVID-19 cases and 5% of COVID-19 deaths lack associated race or ethnicity data. Far fewer states report race and ethnicity for other relevant metrics: only 7 states reported race and ethnicity for testing, and 17 for hospitalizations.

As of September 9, 2020, all 50 states and the District of Columbia were reporting data on COVID-19 infections and/or deaths by race and/or ethnicity. While the number of states reporting race and ethnicity demographics for COVID-19 cases and deaths has improved significantly since April, about 38% of all COVID-19 cases and 5% of COVID-19 deaths lack associated race or ethnicity data. Far fewer states report race and ethnicity for other relevant metrics: only 7 states reported race and ethnicity for testing, and 17 for hospitalizations.

In addition to many COVID-19 metrics lacking associated race and ethnicity data, data are particularly limited for Asian, Alaska Native/American Indian (AIAN), and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (NHPI) populations. Many states do not report data for these groups, and data reporting for AIAN populations is further complicated by overlapping state, tribal, and county reporting jurisdictions. These data limitations represent a considerable challenge to measuring disparities in COVID-19 outcomes among minorities.

Racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19 cases and deaths

As more data have become available, the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on minority communities has become clear. Using data from the COVID Tracking Project, we quantified disparities in COVID-19 cases and deaths. We used this data to explore the disparity landscape across the U.S. among the U.S. Census Bureau’s racial and ethnic categories (Black, Asian, Alaska Native/American Indian, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, White, and Latino/Hispanic).

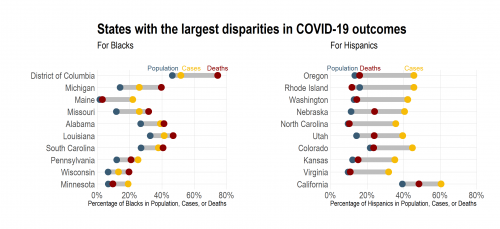

Large disparities exist in COVID-19 outcomes among the two largest racial/ethnic groups, Blacks and Hispanics. Exhibit 2 shows the states with the largest absolute difference between the population of Blacks or Hispanics and their proportion of either cases or deaths. For Blacks, several of the states with the largest disparities for COVID-19 cases have even larger disparities for COVID-19 deaths. In contrast, Hispanics are significantly overrepresented in COVID-19 cases in many states, but disparities in COVID-19 deaths for Hispanics tend to be smaller.

However, this does not mean that Hispanics do not experience severe illness due to the coronavirus — in fact, Hispanics are overrepresented in nearly all of the 16 states currently reporting ethnicity for hospitalizations. Despite disparities in COVID-19 outcomes, Blacks make up a near-proportional number of tests in 7 reporting states, and Hispanics in 6 out of 7 reporting states. Given that Blacks and Hispanics make up a greater than proportional number of COVID-19 cases, this likely means that Blacks and Hispanics are being under-tested.

Data on COVID-19 outcomes are more limited for Asians, Alaska Native/American Indian, and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (NHPI) populations. However, where data are available, we found that disparities exist for these populations as well. For Asians, disparities in both COVID-19 cases and deaths are present in some states, but are not as geographically widespread as the disparities observed for Black and Hispanic populations. In Hawaii, NHPI make up approximately 10% of the population but 43% of COVID-19 cases. Similarly, a disproportionate impact of COVID-19 has been observed in AIAN populations. As an example, the Navajo Nation has experienced a particularly high case burden, with over 5% of the population contracting COVID-19 by July, compared to 2.7% of New York City residents at that time. Furthermore, disparities in AIAN populations can be seen throughout AIAN populations in Arizona.

In contrast to the widespread disparities observed for minority populations, non-Hispanic Whites are underrepresented in COVID-19 cases and deaths in the majority of U.S. states, and also experience lower hospitalization rates than minority populations.

State-level data doesn’t tell the whole story

More granular data can provide greater insight into the presence and extent of racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19 outcomes. We collected race and ethnicity demographics for COVID-19 cases from the Department of Health websites of six states: Arizona, Florida, Illinois, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Virginia. In all cases, we observed considerable variation in the size of disparities between counties. Furthermore, in all six states, larger proportions of one or more minority groups were associated with higher COVID-19 case burden (defined as the percentage of the county population that has tested positive). However, case burden was not associated with population size, indicating that these results cannot be explained by minority prevalence in urban counties. These results are consistent with other recent studies that have shown a disproportionate number of cases occur in areas with large minority populations.

Ongoing challenges and conclusions

Currently available data indicate significant, widespread disparities in COVID-19 cases and deaths for Black, Hispanic, and American Indian populations, and suggest that disparities may also exist in some locations for Asian and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander populations. However, many data gaps and challenges remain for evaluating the nature of these disparities. Although data reporting on race and ethnicity has improved considerably, nearly 38% of all COVID-19 cases as of September 2020 did not have associated race and ethnicity data.

Inconsistency in the race/ethnicity categories used also hinders comparisons to existing population data. Although state-level data are insufficient to fully characterize the impact of COVID-19 on minority communities, data are extremely limited at county or municipal levels. With county-level data from six states, we observed that disparities persist in rural, suburban, and urban counties and counties with high minority population tend to have high COVID-19 case burden. Efforts to improve data reporting, comprehensiveness, and granularity will be critical to understand the impact of COVID-19 on minority populations. Linking this information to social determinants of health data will provide further insight into the causes and potential policy solutions to address racial and ethnic disparities in the COVID-19 pandemic.

The post A Survey of Racial and Ethnic Disparities in COVID-19 Outcomes at State, Tribal, and County Levels first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

November 9, 2020

Healthcare Triage Podcast: How We Study Alzheimer’s and Potential Treatments

Aaron Carroll talks with Dr. Bruce Lamb and Dr. Alan Palkowitz about Alzheimer’s disease. They discuss how they’re combining their different backgrounds and strengths – basic science in university research for Lamb and drug discovery in the pharmaceutical industry for Palkowitz – as they work to develop potential treatments for Alzheimer’s disease.

This episode of the Healthcare Triage podcast is sponsored by Indiana University School of Medicine whose mission is to advance health in the state of Indiana and beyond by promoting innovation and excellence in education, research and patient care.

IU School of Medicine is leading Indiana University’s first grand challenge, the Precision Health Initiative, with bold goals to cure multiple myeloma, triple negative breast cancer and childhood sarcoma and prevent type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease.

Available where you get your podcasts! Including iTunes

The post Healthcare Triage Podcast: How We Study Alzheimer's and Potential Treatments first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

Improving HPV Vaccination Rates: A Stepped-Wedge Randomized Trial

Elsa Pearson, MPH, is a senior policy analyst at Boston University School of Public Health. She tweets at @epearsonbusph.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States, with almost 80 million individuals infected. HPV causes genital warts and a variety of cancers. Thankfully, there is a highly effective vaccine available, shown to decrease rates of cervical cancer among young women. It’s recommended that all adolescents get vaccinated against HPV but persistent concerns about safety and provider- and system-level challenges can negatively impact vaccination rates. Thus, interventions to increase initiation and completion of the HPV vaccine series are critical to improve public health.

Study Design

In an effort to determine if clinic-level education initiatives could improve HPV vaccination rates, Rebecca B. Perkins, et al. piloted the Development of Systems and Education for Human Papillomavirus Vaccination (DOSE HPV) intervention.

(The authors hail from a variety of academic and medical institutions. From Boston University: Department of Health Law, Policy and Management, School of Public Health; Continuing Medical Education Office; Evans Center for Implementation and Improvement Sciences; Sections of Infectious Diseases and General Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine; Departments of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, School of Medicine and Boston Medical Center. Additionally: Department of Sociology, Stanford University; South Boston Community Health Center; East Boston Neighborhood Health Center; Center for Outcomes, Research, and Evaluation, Maine Medical Center Research Institute.)

DOSE HPV’s three pillars were education and communication training, data assessment and feedback, and clinic-driven action planning. During seven educational sessions, providers learned about clinic-specific pre-intervention data trends, HPV more generally, motivational interviewing, barriers to HPV vaccination, and action plan implementation. Each clinic then developed its own action plan, including systems changes, aimed at improving clinic-wide HPV vaccination uptake. As part of the process, all clinics chose to initiate the vaccine series before age 11.

DOSE HPV was implemented at five clinic sites in the greater Boston area that predominantly serve low-income, minority patients. The 6-8 month study took place between 2016 and 2018. Using a stepped-wedge cluster randomized trial design, clinic sites began DOSE HPV in staggered six-month intervals.

The study population included over 16,000 patients aged 9-17 years who had an assigned primary care provider and at least one clinic visit in the study period.

The primary outcome was series initiation: the likelihood an eligible patient would receive an HPV vaccine dose at a clinic visit, stratified by age. The secondary outcome was on-time series completion: the rate of series completion by the 13th birthday for patients aged 12-13 years. The authors also studied series initiation and completion at the population-level, including all eligible patients.

Results

For 9-10 year olds and 11-12 year olds, the authors found a statistically significant increase in the likelihood an eligible patient would receive an HPV vaccine dose at a clinic visit in the intervention and post-intervention periods. For 13-17 year olds, there was a statistically significant increase during the intervention period but it was not sustained.

The likelihood of vaccination at a clinic visit decreased over time in older age groups compared to youngest (9-10 year olds). This may be because of a “ceiling effect,” as most of the older patients had already initiated the vaccine series.

Perkins, et al. also found a statistically significant increase in the likelihood of on-time completion of the vaccine series in the intervention and post-intervention periods. Lastly, they found DOSE HPV led to statistically significant increases in population-level HPV vaccine coverage; vaccine series initiation and completion rates increased considerably in the intervention and post-intervention periods.

As expected, the study had a few limitations. For example, it was implemented in a specific location and population; generalizability to other geographic areas and demographic groups may be limited. Another challenge was that two clinics transitioned to new electronic medical records during the study period, limiting the authors’ ability to collect specific patient information.

Discussion

The HPV vaccine is a critical public health tool with the potential to greatly reduce sexually transmitted infections and HPV-related cancers. Thus, interventions aimed at improving acceptance and uptake of the vaccine series are vital.

Improving HPV vaccination rates involves a partnership between providers, parents, and health care systems. Providers can help parents by giving clear, evidence-based recommendations, and having the necessary knowledge to answer specific questions. Parents can help providers by entering into a trusting partnership to ensure the best care for the child. Lastly, health care systems can prompt patients, parents, and providers when vaccinations and other preventive services are needed to ensure timely care.

Sustaining improvements in vaccination rates relies heavily on system-level intervention, as Perkins, et al. point out in their paper. An advantage to DOSE HPV was that it was a clinic-level intervention. Thus, the program relied on systems changes and was not entirely dependent on individual providers. It could be more easily sustained over time, with fewer required resources, even when accounting for provider turnover.

Vaccines are one of the most powerful weapons we have against preventable disease. The authors’ findings that DOSE HPV increased HPV vaccination rates is encouraging. Public health experts and clinicians must prioritize vaccine acceptance and uptake through a variety of approaches, including system-level education interventions.

The post Improving HPV Vaccination Rates: A Stepped-Wedge Randomized Trial first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

November 6, 2020

Joe Biden will be president. It matters

Joe Biden has won the 2020 Presidential election. But there is a 6-3 conservative majority on the Supreme Court, and the chances of Democratic control of the Senate seem remote. Therefore, Biden will have difficulty passing legislation, appointing judges, and perhaps even getting his cabinet approved.

I had hoped that a Biden victory and a Democratic recapture of the Senate would give America the chance to pass legislation that would provide better health care to all its citizens. Even more important, we could begin transforming our energy production and distribution systems. We need to develop and implement technologies that will enable us to prosper without destroying the biosphere. None of this looks possible today.

So what is the scope for progressive policy under the Biden administration? Let’s begin with a diagnosis of what was wrong with the Trump administration. For me, the worst feature was a pervasive contempt for empirical facts.

With the Biden victory, we can work to restore competence, professionalism, and integrity to the executive branch of the United States government. We can reform the Centers for Disease Control, which was the world’s leading public health institution and can be again. Biden can work to reconstruct international cooperation on fighting pandemics. We can provide consistent and evidence-based guidance to states and the public on how to mitigate the COVID-19 epidemic. On climate, Biden can rejoin the Paris accords. He can renew federal support for research on advanced energy technologies. He can drop obstructions to California’s efforts to move toward carbon neutrality.

In general, we need to strengthen and, where necessary, cleanse the federal institutions that support science and that collect and curate vital data. We must build out the datasets that accurately describe population health, the social determinants of health, the atmosphere, our freshwater, and the ocean. We must make these data accessible to the public.

These measures are incommensurate to the gravity of our needs, but you do what you can. Our future will depend on our collective ability to learn and drive policy based on what we learn. We can make progress on these fronts with Biden as president, even without the Congress.

The most important book I read on the Trump administration was The Fifth Risk, by Michael Lewis. He makes the case for the importance of competence and empiricism in government.

If your ambition is to maximize short-term gain without regard to the long-term cost, you are better off not knowing the cost. If you want to preserve your personal immunity to the hard problems, it’s better never to really understand those problems. There is an upside to ignorance, and a downside to knowledge. Knowledge makes life messier. It makes it a bit more difficult for a person who wishes to shrink the world to a worldview.

What we can do in the Biden administration is to redirect the US government toward becoming an engine for generating data that enable us to understand the world.

The post Joe Biden will be president. It matters first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

November 2, 2020

How states and localities are enforcing COVID-19 mandates

Caroline La Rochelle , MPH, is a policy and strategy senior associate at PolicyLab at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia .

Physical distancing (also called social distancing) and the wearing of masks are essential to limiting the spread of COVID-19. Many states and localities have made such measures mandatory, and given the current surge in cases and hospitalizations, policymakers across the country are implementing or reinstating rules surrounding business closures and curfews, mask mandates, and gathering size limitations. However, these mandates have incited controversy and even legal challenges, and leaders have struggled to determine how to best enforce them. As pushback against COVID-19 restrictions continues, it is more important than ever to consider how to enforce these measures.

In order to contextualize findings from COVID-Lab, a county-level COVID-19 forecasting model, PolicyLab has continually reviewed policies in all 50 states, and in 31 major metropolitan areas, using state-level policy tracking resources, reviews of relevant executive and agency orders and scans of local media coverage.

Many strategies are being employed to enforce physical distancing and mask mandates. Because restrictions can be legally complex, and evidence is still lacking on the effectiveness of many policies, it’s really not possible to endorse specific enforcement strategies. Rather, it’s more of a hope that this policy scan might help public health officials, researchers and other stakeholders be informed about the range of approaches officials are utilizing.

Enforcement Challenges

Enforcement of COVID-19 mandates is challenging for many reasons. First, concerns about discriminatory enforcement exist. People of color have long been dispropotionately cited for minor infractions, and early evidence from New York City showed disproportionate rates of summonses and arrests in neighborhoods that were majority Black or Latino. The rights of those with disabilities are also important, and it is difficult to confirm whether someone has a true medical exemption from wearing a mask.

Effective enforcement requires buy-in from those tasked with administering penalties. However, after a summer of protests calling for police reform, law enforcement officials have been reluctant to enforce gathering size limitations, concerned about worsening community relations. Many local law enforcement officials have also refused to enforce state mask mandates, stating reasons including personal opposition, limited staff time and capacity, and violations being so common and time bound that they are impractical to enforce.

Monitoring and fining businesses is typically easier than fining individuals because of existing regulatory mechanisms. However, enforcement through businesses raises its own logistical challenges. Both news stories and survey data have highlighted assaults on employees when businesses try to enforce rules. Different businesses may fall under the purview of different agencies, making coordination difficult. Agencies may also lack the capacity and staff to carry out enforcement, and confusing or ambiguous legal definitions may further complicate their efforts. For instance, officials in both Michigan and Virginia described challenges from the lack of clear, readily identifiable distinctions between bars and restaurants.

Finally, lawsuits may impede efforts to impose and enforce mandates. While state and local governments have broad legal authority to issue mask mandates, limitations to sizes of gatherings and business closures risk running afoul of both state and federal laws. For instance, wedding venues have sued under the Fourteenth Amendment, arguing that they should be treated the same way as restaurants, and gathering size restrictions may infringe on the First Amendment, which ensures rights such as peaceful assembly and the free exercise of religion.

Enforcement Strategies

Despite these challenges, across the country, state and local officials are trying a range of interventions to enforce physical distancing and mask mandates. While the precise effects of these efforts (both positive and negative) have largely yet to be determined, policymakers and researchers should watch and evaluate these methods closely.

Enforcement of individual violators

Issuing citations, fines and arrests

Many states and municipalities list potential fines for individuals who violate mandates, but in practice, most locations have little appetite for enforcement of either mask orders or gathering size limitations. Miami has been a prominent exception, using progressively harsher penalties for those who repeatedly violate masking orders, escalating from warnings to fines to arrest. Some California localities have also issued many citations and in some cases have hired private contractors for masking enforcement. In terms of gathering size enforcement, New York City has recently focused on targeting event organizers with hefty fines.

Colleges and universities implementing and enforcing rules

Colleges and universities have tried to impose their own restrictions on students, though in many cases, these rules have failed to change student behavior and prevent unauthorized gatherings. Colleges and universities are trying strategies such as warnings, suspensions, evictions from campus housing, voluntary compliance through education campaigns (often codeveloped with students) and behavioral compacts, encouraging self-reporting and reporting from fellow students, monitoring social media to identify violations, close coordination with local law enforcement, and aggressive testing. The effectiveness of these interventions is often unclear, and punitive measures may come too late to prevent widespread transmission.

Enforcement through businesses

Leveraging existing regulatory mechanisms

Many states and localities are relying on processes already in place for regulatory agencies. For instance, in many states, departments of health, occupational safety bureaus and liquor control boards are enforcing COVID-19-related safety regulations. Some agencies, such as Ohio’s Liquor Control Commission, are conducting many compliance checks but focusing penalties (e.g., citations and suspending liquor licenses) on the most “egregious” offenders. Montana has just stated that they will take a similar approach, targeting businesses with repeated violations and providing more funding to local agencies so they can conduct more compliance checks.

Shifting enforcement of customers who refuse to comply from businesses to law enforcement

Rather than penalizing businesses for the actions of their customers, executive orders and public statements can clarify that businesses are responsible for trying to stop unmasked customers, but that if customers refuse to obey, businesses should call the police. This approach may help relieve the burden of policing from employees, and law enforcement officials have generally expressed more willingness to enforce associated trespassing laws than general mask mandates.

Agency coordination

Centralizing reports about violations

Some authorities are trying to streamline reports of violations. For instance, several counties in Wisconsin have online reporting systems, and the Virginia Department of Health is aggregating complaints from a phone hotline and online survey into a centralized database. Systematic data collection and analysis could allow for more strategic enforcement, though some review would still be required to determine which reports are legitimate.

Creating interagency task forces to coordinate enforcement of mandates

Interagency task forces could help coordinate enforcement and ensure that reports of violations reach the appropriate regulatory body. For instance, Baltimore County has had a six-agency social distancing task force since March, and Massachusetts organized a 10-agency COVID Enforcement and Intervention Team in July.

Other strategies

Mobilizing “compliance ambassadors” and education campaigns

Many government officials have emphasized education and voluntary compliance over punitive approaches, but in order for these approaches to be effective, they will require actual programming and investment. Non-punitive “compliance ambassadors” have been mobilized in places like Las Vegas and Charlotte, N.C., and public education campaigns may also help encourage compliance.

Ensuring that orders allow exceptions for fundamental rights

Gathering size limitations may face less resistance, and be more likely to survive court challenges, if they do not appear to infringe on fundamental rights. In order to protect First Amendment rights, California restrictions on gathering sizes have exceptions for faith-based services, cultural ceremonies and protests. Similarly, Connecticut allows religious gatherings and graduations to have higher capacity limits than other private gatherings.

Shutting off utilities

In Los Angeles, properties that repeatedly violate gathering size restrictions can have their utilities shut off.

Enforcement of COVID-19 restrictions will likely continue to be challenging. However, by laying out a broad range of approaches being used, stakeholders can identify and study potential interventions to determine which enforcement mechanisms are most effective for their communities.

The post How states and localities are enforcing COVID-19 mandates first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

October 30, 2020

Call for Abstracts: Special Issue of HSR on International Comparisons of High-Need, High-Cost Patients

Health Services Research (HSR) and the International Collaborative on Costs, Outcomes and Needs In Care (ICCONIC) are partnering to publish a Special Issue on International Comparisons of High-Need, High-Cost Patients: New Directions in Research and Policy. The issue is sponsored by The Health Foundation and the abstract submission deadline is November 30, 2020. A few more details below and even more here.

The goal of this Special Issue is to highlight cutting-edge work that showcase the potential to learn from international comparisons of high-need, high-cost individuals. A portion of the Special Issue will feature the work of the International Collaborative on Costs, Outcomes and Needs in Care (ICCONIC). ICCONIC consists of 12 partners from North America, Europe and the Pacific who use national and regional patient-level datasets to explore variations in the utilization and costs of health services for particular types of high-need individuals. The rest of the Special Issue will consist of invited submissions that examine areas related to the delivery of care for high-need, high cost-individuals.

We strongly encourage cutting-edge research that opens up new frontiers in the study of high-need, high-cost patients and that delineates key questions that can be addressed in future investigation. Papers that offer a comparative perspective from more than one health system will be prioritized. Papers that are opinion pieces or reviews will not be considered. While the issue may include a framework/review paper and/or a summary/commentary, these will be solicited separately.

Please see the full description and submission details here.

The post Call for Abstracts: Special Issue of HSR on International Comparisons of High-Need, High-Cost Patients first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

October 28, 2020

Acetaminophen, Risk-Taking, and Covid-19

Does the world’s most common pain relief drug do more than just reduce pain? Recent headlines would have you believe that it also reduces your perception of risk, resulting in more risk-taking behaviors. We think it’s time to take a closer look at the details before deciding to ditch the Tylenol.

The post Acetaminophen, Risk-Taking, and Covid-19 first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

Recent publications from Boston University’s Department of Health Law, Policy and Management: October 2020 Edition

Below are recent peer-reviewed publications from Boston University’s Department of Health Law, Policy and Management. You can find all posts in this series here. After an extended summer hiatus, we’re playing a bit of catch up here, so this edition is unusually long.

October 2020 Edition

Annas GJ. Genome Editing 2020: Ethics and Human Rights in Germline Editing in Humans and Gene Drives in Mosquitoes. Am J Law Med. 2020 05; 46(2-3):143-165. PMID: 32659189.

Annas GJ. Planetary Ethics: Russell Train and Richard Nixon at the Creation. Hastings Cent Rep. 2020 May; 50(3):23-24. PMID: 32596907.

Annas GJ. Rationing Crisis: Bogus Standards of Care Unmasked by Covid-19. Am J Bioeth. 2020 07; 20(7):167-169. PMID: 32716806.

Auty SG, Stein MD, Walley AY, Drainoni ML. Buprenorphine waiver uptake among nurse practitioners and physician assistants: The role of existing waivered prescriber supply. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2020 Aug; 115:108032. PMID: 32600629.

Barlam TF, Childs E, Zieminski SA, Meshesha TM, Jones KE, Butler JM, Damschroder LJ, Goetz MB, Madaras-Kelly K, Reardon CM, Samore MH, Shen J, Stenehjem E, Zhang Y, Drainoni ML. Perspectives of Physician and Pharmacist Stewards on Successful Antibiotic Stewardship Program Implementation: A Qualitative Study. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020 Jul; 7(7):ofaa229. PMID: 32704510.

Bashar S, Han D, Fearass Z, Ding E, Fitzgibbons T, Walkey A, McManus D, Javidi B, Chon K. Novel Density Poincare Plot Based Machine Learning Method to Detect Atrial Fibrillation from Premature Atrial/Ventricular Contractions. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2020 Jun 23; PP. PMID: 32746035.

Bashar S, Hossain MB, Ding E, Walkey A, McManus D, Chon K. Atrial Fibrillation Detection during Sepsis: Study on MIMIC III ICU Data. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2020 May 15; PP. PMID: 32750900.

Benzer JK, Gurewich D, Singer SJ, McIntosh NM, Mohr DC, Vimalananda VG, Charns MP. A Mixed Methods Study of the Association of Non-Veterans Affairs Care With Veterans’ and Clinicians’ Experiences of Care Coordination. Med Care. 2020 08; 58(8):696-702. PMID: 32692135.

Brady KJS, Ni P, Sheldrick RC, Trockel MT, Shanafelt TD, Rowe SG, Schneider JI, Kazis LE. Describing the emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and low personal accomplishment symptoms associated with Maslach Burnout Inventory subscale scores in US physicians: an item response theory analysis. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2020 Jun 01; 4(1):42. PMID: 32488344.

Cole MB, Ellison JE, Trivedi AN. Association Between High-Deductible Health Plans and Disparities in Access to Care Among Cancer Survivors. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Jun 01; 3(6):e208965. PMID: 32579191.

Cole MB. The Five-Year Effect of Medicaid Expansion on Community Health Centers: Coverage, Quality of Care, and Service Volume. Health Serv Res. 2020; 55(S1):38-39.

Connolly SL, Etingen B, Shimada SL, Hogan TP, Nazi K, Stroupe K, Smith BM. Patient portal use among veterans with depression: Associations with symptom severity and demographic characteristics. J Affect Disord. 2020 Oct 01; 275:255-259. PMID: 32734917.

Crosby SS, Annas GJ. Border Babies – Medical Ethics and Human Rights in Immigrant Detention Centers. N Engl J Med. 2020 Jul 23; 383(4):297-299. PMID: 32706532.

Crosby SS. My COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Aug 11. PMID: 32777184.

Crowe HM, Wise LA, Wesselink AK, Rothman KJ, Mikkelsen EM, Sørensen HT, Walkey AJ, Hatch EE. Association of Asthma Diagnosis and Medication Use with Fecundability: A Prospective Cohort Study. Clin Epidemiol. 2020; 12:579-587. PMID: 32606983.

Dismuke-Greer C, Hirsch S, Carlson K, Pogoda T, Nakase-Richardson R, Bhatnagar S, Eapen B, Troyanskaya M, Miles S, Nolen T, Walker WC. Health Services Utilization, Health Care Costs, and Diagnoses by Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Exposure: A Chronic Effects of Neurotrauma Consortium Study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2020 Oct; 101(10):1720-1730. PMID: 32653582.

Dryden EM, Hyde JK, Wormwood JB, Wu J, Calloway R, Cutrona SL, Elwyn G, Fix GM, Orner MB, Shimada SL, Bokhour BG. Assessing Patients’ Perceptions of Clinician Communication: Acceptability of Brief Point-of-Care Surveys in Primary Care. J Gen Intern Med. 2020 Aug 03. PMID: 32748346.

Frakt AB, Jha AK, Glied S. Pivoting from decomposing correlates to developing solutions: An evidence-based agenda to address drivers of health. Health Serv Res. 2020 Oct; 55 Suppl 2:781-786. PMID: 32776528.

Garcia A, Reljic T, Pogoda TK, Kenney K, Agyemang A, Troyanskaya M, Belanger HG, Wilde EA, Walker WC, Nakase-Richardson R. Obstructive Sleep Apnea Risk Is Associated with Cognitive Impairment after Controlling for Mild Traumatic Brain Injury History: A Chronic Effects of Neurotrauma Consortium Study. J Neurotrauma. 2020 Sep 01. PMID: 32709212.

Griffith KN, Prentice JC, Mohr DC, Conlin PR. Predicting 5- and 10-Year Mortality Risk in Older Adults With Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2020 Aug; 43(8):1724-1731. PMID: 32669409.

Gunn C, Bernstein J, Bokhour B, McCloskey L. Narratives of Gestational Diabetes Provide a Lens to Tailor Postpartum Prevention and Monitoring Counseling. J Midwifery Women’s Health. 2020 Jun 22. PMID: 32568461.

Hazzard VM, Simone M, Borg SL, Borton KA, Sonneville KR, Calzo JP, Lipson SK. Disparities in eating disorder risk and diagnosis among sexual minority college students: Findings from the national Healthy Minds Study. Int J Eat Disord. 2020 Sep; 53(9):1563-1568. PMID: 32449541.

Huberfeld N, Gordon SH, Jones DK. Federalism Complicates the Response to the COVID-19 Health and Economic Crisis: What Can Be Done? J Health Polit Policy Law. 2020 May 28. PMID: 32464666.

Iaccarino JM, Steiling K, Slatore CG, Drainoni ML, Wiener RS. Patient characteristics associated with adherence to pulmonary nodule guidelines. Respir Med. 2020 Sep; 171:106075. PMID: 32658836.

Kenney SR, Anderson BJ, Bailey GL, Herman DS, Conti MT, Stein MD. Examining Overdose and Homelessness as Predictors of Willingness to Use Supervised Injection Facilities by Services Provided Among Persons Who Inject Drugs. Am J Addict. 2020 Jun 10. PMID: 32519449.

Kim JH, Desai E, Cole MB. How The Rapid Shift To Telehealth Leaves Many Community Health Centers Behind During The COVID-19 Pandemic. Health Affairs Blog. 2020.

Ko D, Kapoor A, Rose AJ, Hanchate AD, Miller D, Winter MR, Palmisano JN, Henault LE, Fredman L, Walkey AJ, Tripodis Y, Karcz A, Hylek EM. Temporal trends in pharmacologic prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism after hip and knee replacement in older adults. Vasc Med. 2020 Jun 09; 1358863X20927096. PMID: 32516054.

Mackie TI, Ramella L, Schaefer AJ, Sridhar M, Carter AS, Eisenhower A, Ibitamuno GT, Petruccelli M, Hudson SV, Sheldrick RC. Multi-method process maps: An interdisciplinary approach to investigate ad hoc modifications in protocol-driven interventions. J Clin Transl Sci. 2020 Feb 26; 4(3):260-269. PMID: 32695498.

Meshesha LZ, Aston ER, Teeters JB, Blevins CE, Battle CL, Marsh E, Feltus S, Stein MD, Abrantes AM. Evaluating alcohol demand, craving, and depressive symptoms among women in alcohol treatment. Addict Behav. 2020 10; 109:106475. PMID: 32480282.

Miller C, Gurewich D, Garvin L, Pugatch M, Koppelman E, Pendergast J, Harrington K, Clark JA. Veterans Affairs and Rural Community Providers’ Perspectives on Interorganizational Care Coordination: A Qualitative Analysis. J Rural Health. 2020 May 30. PMID: 32472724.

Nikpay S, Pungarcher I, Frakt A. An Economic Perspective on the Affordable Care Act: Expectations and Reality. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2020 Oct 01; 45(5):889-904. PMID: 32589202.

O’Hanlon CE, Lindvall C, Lorenz KA, Giannitrapani KF, Garrido M, Asch SM, Wenger N, Malin J, Dy SM, Canning M, Gamboa RC, Walling AM. Measure Scan and Synthesis of Palliative and End-of-Life Process Quality Measures for Advanced Cancer. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020 Aug 06; OP2000240. PMID: 32758085.

Ornstein KA, Garrido MM, Bollens-Lund E, Husain M, Ferreira K, Kelley AS, Siu AL. Estimation of the Incident Homebound Population in the US Among Older Medicare Beneficiaries, 2012 to 2018. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Jul 01; 180(7):1022-1025. PMID: 32453343.

Ornstein KA, Garrido MM, Bollens-Lund E, Reckrey JM, Husain M, Ferreira KB, Liu SH, Ankuda CK, Kelley AS, Siu AL. The Association Between Income and Incident Homebound Status Among Older Medicare Beneficiaries. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020 Aug 10. PMID: 32776512.

Orr LC, Graham AK, Mohr DC, Greene CJ. Engagement and Clinical Improvement Among Older Adult Primary Care Patients Using a Mobile Intervention for Depression and Anxiety: Case Studies. JMIR Ment Health. 2020 Jul 08; 7(7):e16341. PMID: 32673236.

Pearson E, Frakt A. Health Care Cost Growth Benchmarks in 5 States. JAMA. 2020 Aug 11; 324(6):537-538. PMID: 32780131.

Perkins RB, Legler A, Jansen E, Bernstein J, Pierre-Joseph N, Eun TJ, Biancarelli DL, Schuch TJ, Leschly K, Fenton ATHR, Adams WG, Clark JA, Drainoni ML, Hanchate A. Improving HPV Vaccination Rates: A Stepped-Wedge Randomized Trial. Pediatrics. 2020 07; 146(1). PMID: 32540986.

Pimentel CB, Mills WL, Snow AL, Palmer JA, Sullivan JL, Wewiorski NJ, Hartmann CW. Adapting Strategies for Optimal Intervention Implementation in Nursing Homes: A Formative Evaluation. Gerontologist. 2020 May 25. PMID: 32449764.

Quach ED, Kazis LE, Zhao S, McDannold SE, Clark VA, Hartmann CW. Relationship Between Work Experience and Safety Climate in Veterans Affairs Nursing Homes Nationwide. J Patient Saf. 2020 Jul 22. PMID: 32701621.

Quach ED, Kazis LE, Zhao S, Ni P, McDannold SE, Clark VA, Hartmann CW. Safety Climate Associated With Adverse Events in Nursing Homes: A National VA Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020 Jul 19. PMID: 32698990.

Raifman J, Bor J, Venkataramani A. Unemployment insurance and food insecurity among people who lost employment in the wake of COVID-19. medRxiv. 2020 Jul 30. PMID: 32766606.

Raifman J, Larson E, Barry CL, Siegel M, Ulrich M, Knopov A, Galea S. State handgun purchase age minimums in the US and adolescent suicide rates: regression discontinuity and difference-in-differences analyses. BMJ. 2020 07 22; 370:m2436. PMID: 32699008.

Raphael JL, Bloom SR, Chung PJ, Guevara JP, Jacobson RM, Kind T, Klein M, Li ST, McCormick MC, Pitt MB, Poehling KA, Trost M, Sheldrick RC, Young PC, Szilagyi PG. Racial Justice and Academic Pediatrics: A Call for Editorial Action and Our Plan to Move Forward. Acad Pediatr. 2020 Aug 11. PMID: 32791317.

Shafer PR, Anderson DM, Aquino SM, Baum LM, Fowler EF, Gollust SE. Competing Public and Private Television Advertising Campaigns and Marketplace Enrollment for 2015 to 2018. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences. 2020; 2(6):85-112.

Shepherd-Banigan M, Pogoda TK, McKenna K, Sperber N, Van Houtven CH. Experiences of VA vocational and education training and assistance services: Facilitators and barriers reported by veterans with disabilities. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2020 Jun 29. PMID: 32597666.

Slavin MD, Ryan CM, Schneider JC, Acton A, Amaya F, Saret C, Ohrtman E, Wolfe A, Ni P, Kazis LE. Interpreting Life Impact Burn Recovery Evaluation (LIBRE) Profile Scores for Use by Clinicians Burn Survivors and Researchers. J Burn Care Res. 2020 Jun 19. PMID: 32556266.

Sosnowy C, Tao J, Nunez H, Montgomery MC, Ndoye CD, Biello K, Mimiaga MJ, Raifman J, Murphy M, Nunn A, Maynard M, Chan PA. Awareness and use of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among people who engage in sex work presenting to a sexually transmitted infection clinic. Int J STD AIDS. 2020 Oct; 31(11):1055-1062. PMID: 32753003.

Stallman HM, Lipson SK, Zhou S, Eisenberg D. How do university students cope? An exploration of the health theory of coping in a US sample. J Am Coll Health. 2020 Jul 16; 1-7. PMID: 32672507.

Stewart MT, Hogan TP, Nicklas J, Robinson SA, Purington CM, Miller CJ, Vimalananda VG, Connolly SL, Wolfe HL, Nazi KM, Netherton D, Shimada SL. The Promise of Patient Portals for Individuals Living With Chronic Illness: Qualitative Study Identifying Pathways of Patient Engagement. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Jul 17; 22(7):e17744. PMID: 32706679.

Sullivan JL, Weinburg DB, Gidmark S, Engle RL, Parker VA, Tyler DA. Collaborative capacity and patient-centered care in the Veterans’ Health Administration Community Living Centers. Int J Care Coord. 2019 Jun 01; 22(2):90-99. PMID: 32670596.

Vail EA, Wunsch H, Pinto R, Bosch NA, Walkey AJ, Lindenauer PK, Gershengorn HB. Use of Hydrocortisone, Ascorbic Acid, and Thiamine in Adults with Septic Shock. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020 Jul 24. PMID: 32706593.

Vanneman ME, Wagner TH, Shwartz M, Meterko M, Francis J, Greenstone CL, Rosen AK. Veterans’ Experiences With Outpatient Care: Comparing The Veterans Affairs System With Community-Based Care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020 Aug; 39(8):1368-1376. PMID: 32744943.

Wolfe HL, Fix GM, Bolton RE, Ruben MA, Bokhour BG. Development of observational rating scales for evaluating patient-centered communication within a whole health approach to care. Explore (NY). 2020 Jul 05. PMID: 32703684.

Yee CA, Pizer SD, Frakt A. Medicare’s Bundled Payment Initiatives for Hospital-Initiated Episodes: Evidence and Evolution. Milbank Q. 2020 Sep; 98(3):908-974. PMID: 32820837.

Zhu JM, Grande D, Jones DK, Tipirneni R. Health Policy Perspective: Medicaid and State Politics Beyond COVID. J Gen Intern Med. 2020 Aug 19. PMID: 32813219.

Zickgraf HF, Hazzard VM, O’Connor SM, Simone M, Williams-Kerver GA, Anderson LM, Lipson SK. Examining vegetarianism, weight motivations, and eating disorder psychopathology among college students. Int J Eat Disord. 2020 Sep; 53(9):1506-1514. PMID: 32621566.

The post Recent publications from Boston University’s Department of Health Law, Policy and Management: October 2020 Edition first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

October 27, 2020

Measuring Coverage Rates in a Pandemic

My coauthors (Matt Brault and Ben Sommers) and I published a piece in JAMA Health Forum yesterday laying out the challenges inherent to evaluating how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected health coverage. We’ve also put together a table of surveys used to study coverage—including national, nongovernmental surveys fielded by private organizations in response to the pandemic—as a general resource.

The usual-suspect national surveys (ACS, CPS, NHIS) won’t make 2020 data available for months yet. The Census (in coordination with BLS and CDC) did the herculean task of standing up and fielding a rapid-response survey starting in April, but the first wave of the survey had a worryingly low response rate and it’s hard to assess the reliability of its estimates without a pre-pandemic baseline. Private organizations have stepped up to field fast national surveys, but those necessarily obscure important regional variation. Local surveys have sprung up in some places—SHADAC has a great resource of available surveys—but they can’t be directly compared. The pandemic itself has affected survey administration (government surveys were paused in the early spring) and response rates.

Most worryingly, the gold-standard government surveys use coverage metrics that make it hard to understand when in the year someone lost coverage, which will hamper future research. In ordinary times, coverage rates averaged across the year may not be particularly bothersome. But when we’re talking about evaluating a pandemic-recession that has ebbed and flowed across the country, averages fall short of meeting research needs.

Fortunately, better data is possible:

Currently, the CPS Annual Social and Economic Supplement public files report coverage at the time of interview and ever having had coverage in the prior year. The survey collects more granular data—not included in public files—about coverage in each month of the year prior to the interview. The ACS measures coverage at the time of interview and surveys respondents throughout the year but does not disclose the month of interview in its public data release. But a data set that provides a blended average of coverage rates from January, May, and December 2020 obscures the most critical effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. If the Census Bureau released the CPS longitudinal file and the ACS month of interview (or even quarter of interview), with appropriate confidentiality protections in place, this would immeasurably improve researchers’ ability to identify coverage changes before, during, and after the pandemic.

There is precedent for this kind of change in public use files under extraordinary circumstances: for the 2005 ACS, the Census made flags available so that researchers could distinguish between people interviewed before and after Hurricane Katrina in the affected Gulf region. It’s possible that the Census is already considering this kind of accommodation, but we thought that this issue—and available solution—should be on the radar of the broader health services research community.

You can read the full piece here.

Adrianna (@onceuponA)

The post Measuring Coverage Rates in a Pandemic first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers