Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 43

February 11, 2021

Recent publications from Boston University’s Department of Health Law, Policy and Management: February 2021 Edition

Below are recent publications from me and my colleagues from Boston University’s Department of Health Law, Policy and Management. You can find all posts in this series here.

February 2021 Edition

Armstrong MJ, Sullivan JL, Amodeo K, Lunde A, Tsuang DW, Reger MA, Conwell Y, Ritter A, Bang J, Onyike CU, Mari Z, Corsentino P, Taylor A. Suicide and Lewy body dementia: Report of a Lewy body dementia association working group. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020 Nov 09. PMID: 33169435.

Borno HT, Odisho AY, Gunn CM, Pankowska M, Rider JR. Disparities in precision medicine-Examining germline genetic counseling and testing patterns among men with prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2020 Nov 03. PMID: 33158741.

Buchheit BM, Crable EL, Lipson SK, Drainoni ML, Walley AY. “Opening the door to somebody who has a chance.” – The experiences and perceptions of public safety personnel towards a public restroom overdose prevention alarm system. Int J Drug Policy. 2020 Nov 21; 88:103038. PMID: 33232885.

Curyto KJ, Jedele JM, Mohr DC, Eaker A, Intrator O, Karel M. An MDS 3.0 Distressed Behavior in Dementia Indicator (DBDI): A Clinical Tool to Capture Change. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020 Nov 30. PMID: 33253424.

Ellison J, Shafer P, Cole MB. Racial/Ethnic And Income-Based Disparities In Health Savings Account Participation Among Privately Insured Adults. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020 Nov; 39(11):1917-1925. PMID: 33136490.

Feyman Y, Pizer SD, Frakt AB. The persistence of medicare advantage spillovers in the post-Affordable Care Act era. Health Econ. 2020 Nov 21. PMID: 33219715.

Housten AJ, Gunn CM, Paasche-Orlow MK, Basen-Engquist KM. Health Literacy Interventions in Cancer: a Systematic Review. J Cancer Educ. 2020 Nov 05. PMID: 33155097.

Kanwal F, Taylor TJ, Kramer JR, Cao Y, Smith D, Gifford AL, El-Serag HB, Naik AD, Asch SM. Development, Validation, and Evaluation of a Simple Machine Learning Model to Predict Cirrhosis Mortality. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 11 02; 3(11):e2023780. PMID: 33141161.

Morel CM, Alm RA, Årdal C, Bandera A, Bruno GM, Carrara E, Colombo GL, de Kraker MEA, Essack S, Frost I, Gonzalez-Zorn B, Goossens H, Guardabassi L, Harbarth S, Jørgensen PS, Kanj SS, Kostyanev T, Laxminarayan R, Leonard F, Hara GL, Mendelson M, Mikulska M, Mutters NT, Outterson K, Bano JR, Tacconelli E, Scudeller L. A one health framework to estimate the cost of antimicrobial resistance. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2020 11 26; 9(1):187. PMID: 33243302.

Moye J, Stolzmann K, Auguste EJ, Cohen AB, Catlin CC, Sager ZS, Weiskittle RE, Woolverton CB, Connors HL, Sullivan JL. End-of-Life Care for Persons Under Guardianship. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020 Nov 16. PMID: 33212143.

Shafer P, Frakt AB. To Truly Build the Affordable Care Act Into Universal Coverage, More Creativity Is Needed. JAMA. 2020 Nov 17; 324(19):1931-1932. PMID: 33201194.

Shimada SL, Zocchi MS, Hogan TP, Kertesz SG, Rotondi AJ, Butler JM, Knight SJ, DeLaughter K, Kleinberg F, Nicklas J, Nazi KM, Houston TK. Impact of Patient-Clinical Team Secure Messaging on Communication Patterns and Patient Experience: Randomized Encouragement Design Trial. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Nov 18; 22(11):e22307. PMID: 33206052.

Walkey AJ, Sheldrick RC, Kashyap R, Kumar VK, Boman K, Bolesta S, Zampieri FG, Bansal V, Harhay MO, Gajic O. Guiding Principles for the Conduct of Observational Critical Care Research for Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemics and Beyond: The Society of Critical Care Medicine Discovery Viral Infection and Respiratory Illness Universal Study Registry. Crit Care Med. 2020 11; 48(11):e1038-e1044. PMID: 32932348.

Yan LD, Ali MK, Strombotne KL. Impact of Expanded Medicaid Eligibility on the Diabetes Continuum of Care Among Low-Income Adults: A Difference-in-Differences Analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2020 Nov 10. PMID: 33191065.

The post Recent publications from Boston University’s Department of Health Law, Policy and Management: February 2021 Edition first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

February 10, 2021

Out-of-network payments in Medicare Advantage

This post is coauthored by Austin Frakt and Tynan Friend (@TynanFriend), currently a Research Assistant in the Department of Health Policy and Management at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. We thank Michael Chernew and Michael Adelberg for their comments on earlier drafts of this post.

The complexity of Medicare Advantage (MA) physician networks has been well-documented, but the payment regulations that underlie these plans remain opaque, even to experts. If an MA plan enrollee sees an out-of-network doctor, how much should she expect to pay?

The answer, like much of the American healthcare system, is complicated. We’ve consulted experts and scoured nearly inscrutable government documents to try to find it. In this post we try to explain what we’ve learned in a much more accessible way.

Medicare Advantage Basics

Medicare Advantage is the private insurance alternative to traditional Medicare (TM), comprised largely of HMO and PPO options. One-third of the 60+ million Americans covered by Medicare are enrolled in MA plans. These plans, subsidized by the government, are governed by Medicare rules, but, within certain limits, are able to set their own premiums, deductibles, and service payment schedules each year.

Critically, they also determine their own network extent, choosing which physicians are in- or out-of-network. Apart from cost sharing or deductibles, the cost of care from providers that are in-network is covered by the plan. However, if an enrollee seeks care from a provider who is outside of their plan’s network, what the cost is and who bears it is much more complex.

Provider Types

To understand the MA (and enrollee) payment-to-provider pipeline, we first need to understand the types of providers that exist within the Medicare system.

Participating providers, which constitute about 97% of all physicians in the U.S., accept Medicare Fee-For-Service (FFS) rates for full payment of their services. These are the rates paid by TM. These doctors are subject to the fee schedules and regulations established by Medicare and MA plans.

Non-participating providers (about 2% of practicing physicians) can accept FFS Medicare rates for full payment if they wish (a.k.a., “take assignment”), but they generally don’t do so. When they don’t take assignment on a particular case, these providers are not limited to charging FFS rates.

Opt-out providers don’t accept Medicare FFS payment under any circumstances. These providers, constituting only 1% of practicing physicians, can set their own charges for services and require payment directly from the patient. (Many psychiatrists fall into this category: they make up 42% of all opt-out providers. This is particularly concerning in light of studies suggesting increased rates of anxiety and depression among adults as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic).

How Out-of-Network Doctors are Paid

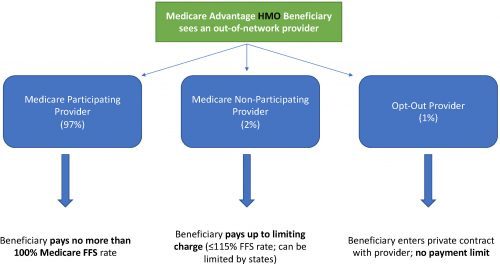

So, if an MA beneficiary goes to see an out-of-network doctor, by whom does the doctor get paid and how much? At the most basic level, when a Medicare Advantage HMO member willingly seeks care from an out-of-network provider, the member assumes full liability for payment. That is, neither the HMO plan nor TM will pay for services when an MA member goes out-of-network.

The price that the provider can charge for these services, though, varies, and must be disclosed to the patient before any services are administered. If the provider is participating with Medicare (in the sense defined above), they charge the patient no more than the standard Medicare FFS rate for their services. Non-participating providers that do not take assignment on the claim are limited to charging the beneficiary 115% of the Medicare FFS amount, the “limiting charge.” (Some states further restrict this. In New York State, for instance, the maximum is 105% of Medicare FFS payment.) In these cases, the provider charges the patient directly, and they are responsible for the entire amount (See Figure 1.)

Alternatively, if the provider has opted-out of Medicare, there are no limits to what they can charge for their services. The provider and patient enter into a private contract; the patient agrees to pay the full amount, out of pocket, for all services.

Figure 1: MA HMO Out-of-Network Payments

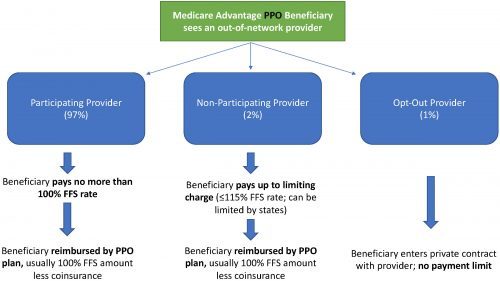

MA PPO plans operate slightly differently. By , there are built-in benefits covering visits to out-of-network physicians (usually at the expense of higher annual deductibles and co-insurance compared to HMO plans). Like with HMO enrollees, an out-of-network Medicare-participating physician will charge the PPO enrollee no more than the standard FFS rate for their services. The PPO plan will then reimburse the enrollee 100% of this rate, less coinsurance. (See Figure 2.)

In contrast, a non-participating physician that does not take assignment is limited to charging a PPO enrollee 115% of the Medicare FFS amount, which can be further limited by state regulations. In this case, the PPO enrollee is also reimbursed by their plan up to 100% (less coinsurance) of the FFS amount for their visit. Again, opt-out physicians are exempt from these regulations and must enter private contracts with patients.

Figure 2: MA PPO Out-of-Network Payments

Some Caveats

There are two major caveats to these payment schemes (with many more nuanced and less-frequent exceptions detailed here). First, if a beneficiary seeks urgent or emergent care (as defined by Medicare) and the provider happens to be out-of-network for the MA plan (regardless of HMO/PPO status), the plan must cover the services at their established in-network emergency services rates.

The second caveat is in regard to the declared public health emergency due to COVID-19 (set to expire in April 2021, but likely to be extended). MA plans are currently required to cover all out-of-network services from providers that contract with Medicare (i.e., all but opt-out providers) and charge beneficiaries no more than the plan-established in-network rates for these services. This is being mandated by CMS to compensate for practice closures and other difficulties of finding in-network care as a result of the pandemic.

Conclusion

Outside of the pandemic and emergency situations, knowing how much you’ll need to pay for out-of-network services as a MA enrollee depends on a multitude of factors. Though the vast majority of American physicians contract with Medicare, the intersection of insurer-engineered physician networks and the complex MA payment system could lead to significant unexpected costs to the patient.

The post Out-of-network payments in Medicare Advantage first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

February 8, 2021

Cancer Journal: What is health?

What is health? Take a moment to answer that question.

Was that exercise helpful? In particular, do you think that how you understand health would affect your health care choices?

I thought through what health means last Thursday during a follow-up appointment with my oncologist. Going into the visit, I was concerned about the persisting pain at the tumour site in my throat. As is common for throat cancers, that pain radiates to one of my inner ears.

An endoscope. The thin end gets inserted into your nose.

At the visit, an endoscope was threaded into my nose, through my sinuses, and down my throat. (It’s easier than it sounds.) The camera in the scope projected video of the inside of my throat onto a big screen. When I was scoped before radiation, I could see a large, reddish mass that partially occluded my throat: the notorious tumour. But now it’s gone! The flesh was pink, and there wasn’t even a scar.

This is a good result, but it is just one data point. Cancer’s a wily bastard, and it still has ways to kill me. But it’s a data point nevertheless, which raises the odds of my long-term survival.

But what about the pain? “Well,” said my oncologist, “that may go away over time.” Or. It may not. “It may not,” my doctor agreed. Perhaps the tumour — or the radiation treatment — inflicted damage to my nerves that won’t resolve.

This brings us to the question of what health is. In this case, how much does pain count in my health choices? I expect that everyone will agree that everything else being equal; health includes the expectation of a long life in which you feel good and function well in your life tasks. OK, but what if life doesn’t offer you the choice of maximizing all three?

My oncologist and I get on well, but we have disagreed several times about the best course of care. He recommended that I should have radiation and chemotherapy, but I chose only the former. And he felt that I was not taking enough pain medication. Specifically, he thought that I should start hydromorphone (Dilaudid, an opioid) earlier than I wanted to and that I should take higher doses to get through treatment.

I’ll call this the hedonic view of health: what matters most is living a long time and feeling good.

But I wanted to maximize functioning. I declined cisplatin (a chemotherapeutic drug) because of concern about the risk of persistent cognitive and psychiatric harms. Cisplatin is, after all, a poison that affects your entire body, including the brain, and not just the tumour. By refusing chemotherapy, however, I accepted a reduction in my life expectancy. I also took as little Dilaudid as I could manage because it increased the listlessness I felt because of radiation. That means that I suffered more than I had to. But I was (at least partially) awake and got a few things done.

Let’s call this the capability view of health: health is the ability to do stuff. What I want from life are opportunities to be engaged in attempting hard things. So, a longer life is great, but not if it comes at too high a cost in capabilities. The same goes for being pain-free. Pain is a signal in challenging efforts, potentially distracting, potentially useful. I’ll suppress it with drugs if it gets disabling. Short of that, however, I’d rather attend to pain and see if I can learn something from it, and steer a better course.

I’m not arguing for this view of life. Excessive focus on your own capabilities at the expense of others’ needs is a vice. My oncologist’s views probably reflect what most of his patients want, and what they want has the same moral value as what I want.

My point, however, is that health is not just an objective physiological state. It’s how we value those states. In life and death conversations — and cancer prompts those — doctors have to listen to what patients want. They need to give them the necessary information to understand the tradeoffs life offers them concerning those goals.

To read the Cancer Posts from the start, please begin here.

The post Cancer Journal: What is health? first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

February 5, 2021

Should You Worry About Covid Vaccine Side Effects?

As the vaccine to protect against Covid-19 continues to roll out to more and more people, interest in side effects is high. This can lead to lots of media coverage when people experience side effects, particularly when serious side effects occur. We’re here to talk about side effects and put some of these stories in context, which will hopefully leave less room for disiformation and scare tactics to be part of the conversation.

Thanks to Bill and Melinda Gates for supporting Healthcare Triage. Head to https://bit.ly/HCTSponsor to read this year’s Annual Letter detailing what we need to do for better health and a better future.

The post Should You Worry About Covid Vaccine Side Effects? first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

February 2, 2021

U.S. should prepare for a COVID-19 hospital consolidation surge

Grace Flaherty (@graceflaherty10) is a recent graduate of Tufts University’s MS & MPH program. She specializes in health care policy and nutrition policy and has prior professional experience at the Massachusetts Health Policy Commission and the U.S. Senate.

The COVID-19 pandemic has created a buyer’s market for large health systems looking to acquire struggling hospitals hard-hit by the pandemic. Despite claims that mergers bring greater efficiencies and more coordinated care, research suggests that consolidation increases health care costs and does not meaningfully improve quality. In addition to continuing antitrust investigations, three policy options can help maintain competition in U.S. health care markets.

Hospitals are suffering financially due to COVID-19

The pandemic has brought many hospitals to their knees. With a dramatic reduction in routine procedures and the added costs of caring for COVID-19 patients, U.S. hospitals and health systems suffered an estimated $202.6 billion in total losses between March and June alone.

Hospitals in rural and low-income areas are particularly vulnerable to these losses. Even before the pandemic, 25 percent of rural hospitals were experiencing financial strain and were at “high risk of closing.” These rural hospitals are important for maintaining health care access in the surrounding communities.

The federal government has passed billions of dollars in pandemic bailout funds to aid hospitals, but distribution of the funds has been unbalanced, favoring larger, wealthier hospital systems. As a result, some of the hard-hit small independent hospitals may close after the pandemic, leaving patients with fewer options for care.

Mergers involving financially distressed hospitals may speed up following the pandemic

Rather than close their doors during times of financial distress, independent hospitals can choose to merge with larger health systems. This is a growing trend in the U.S. health care system, which is becoming increasingly consolidated — dominated by fewer, larger health care organizations.

Now, with financial conditions deteriorating for hospitals during the pandemic, there is even more incentive for smaller independent hospitals to merge with the dominant health systems or risk going out of business.

Mergers lead to higher costs without improving quality

In theory, streamlining the health care system into a few health systems rather than maintaining a patchwork of hospitals may seem like a good idea. However, research suggests that when hospitals merge, patients lose.

Hospital administrators and national hospital associations defend mergers and acquisitions, claiming they will lead to better coordination, lower costs, and improved patient care. The American Hospital Association has published research on mergers’ consequences, which found reductions in operating expenses at acquired hospitals, reductions in readmission and mortality rates, and savings for health plans.

However, most evidence from antitrust experts suggests that hospital mergers lead to price increases and higher premiums for patients because there is less competition in the marketplace.

California provides an example of how mergers affect patients’ pocketbooks. Northern California has seen more rapid health system consolidation than Southern California. A 2018 study measuring the effect of this consolidation found that health care prices in Northern California were between 20-30 percent higher and Affordable Care Act premiums were 35 percent higher than in Southern California.

You might expect that a higher price tag means better care, but these price and premium increases are occurring without improvements in efficiency or quality. A 2020 study from Harvard researchers compared 246 acquired hospitals to 1,986 control hospitals and found that consolidation did not improve hospital performance and patient-experience scores deteriorated somewhat after the mergers.

Policies can mitigate the effects of COVID-19 hospital mergers

State and federal authorities should continue to investigate new hospital mergers and challenge potential threats to competition. However, beyond legal action, policymakers should consider three additional policy options to help promote competition and control costs.

First, merging health care entities can be split into separate bargaining units. This strategy was used by the Federal Trade Commission in the case of the Evanston merger in 2007. In theory, this policy allows patients to keep access to hospitals while hopefully keeping costs lower because insurers are bargaining with individual hospitals. However, in the case of Evanston, although payers had the option to negotiate separately with the merged hospitals, none took advantage, suggesting that they recognize the benefits are minimal.

A second option is for states to protect tiered networks, where insurers group hospitals into levels based on cost and quality of care. Tiered networks have been shown to reduce spending by steering patients toward lower cost, higher value care with cost sharing incentives. Massachusetts has passed — and other states have introduced — legislation prohibiting hospital systems from including “anti-steering” or “all-or-nothing” clauses in their contracts, thus allowing insurers to freely tier hospitals in their plans.

A third route is for states to monitor and control total health care costs through spending targets. Massachusetts was the first state to establish a cost growth benchmark with the power to penalize entities who exceed the benchmark, and other states are beginning to follow suit. Penalties for health care entities exceeding the benchmark may include fines and performance improvement plans.

These three policies cannot stop hospital mergers from occurring, but they can help reduce the degree to which consolidation drives health care prices higher. In the event of a post-COVID-19 surge in hospital mergers, these and other policies will be important for minimizing its impact on health care budgets.

The post U.S. should prepare for a COVID-19 hospital consolidation surge first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

February 1, 2021

Can You Get Reinfected with Covid?

Reports have surfaced of individuals being re-infected with Covid-19, raising questions about immunity via natural infection as well as questions about the utility of vaccines. Here we take a look at the data to see how common reinfection is and what that means in the grand scheme of things.

The post Can You Get Reinfected with Covid? first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

January 28, 2021

Recent publications from Boston University’s Department of Health Law, Policy and Management: January 2021 Edition

Below are recent publications from me and my colleagues from Boston University’s Department of Health Law, Policy and Management. You can find all posts in this series here.

January 2021 Edition

Abelson S, Lipson SK, Zhou S, Eisenberg D. Muslim Young Adult Mental Health and the 2016 US Presidential Election. JAMA Pediatr. 2020 Oct 05. PMID: 33016990.

Bashar SK, Han D, Zieneddin F, Ding E, Walkey AJ, McManus DD, Chon KH. Preliminary Results on Density Poincare Plot Based Atrial Fibrillation Detection from Premature Atrial/Ventricular Contractions. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2020 07; 2020:2594-2597. PMID: 33018537.

Bosch NA, Fantasia KL, Modzelewski KL, Alexanian SM, Walkey AJ. Racial Disparities in Guideline-concordant Insulin Infusions during Critical Illness. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020 Oct 01. PMID: 33001705.

Cole MB, Nguyen KH. Unmet social needs among low-income adults in the United States: Associations with health care access and quality. Health Serv Res. 2020 Oct; 55 Suppl 2:873-882. PMID: 32880945.

Crable EL, Biancarelli DL, Aurora M, Drainoni ML, Walkey AJ. Interventions to increase appointment attendance in safety net health centers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020 Oct 16. PMID: 33064929.

Etingen B, Amante DJ, Martinez RN, Smith BM, Shimada SL, Richardson L, Patterson A, Houston TK, Frisbee KL, Hogan TP. Supporting the Implementation of Connected Care Technologies in the Veterans Health Administration: Cross-Sectional Survey Findings from the Veterans Engagement with Technology Collaborative (VET-C) Cohort. J Particip Med. 2020 Sep 30; 12(3):e21214. PMID: 33044944.

Fernandez WG, Benzer JK, Charns MP, Burgess JF. Applying a Model of Teamwork Processes to Emergency Medical Services. West J Emerg Med. 2020 Oct 19; 21(6):264-271. PMID: 33207175.

Freeman R, Coyne J, Kingsdale J. Successes and failures with bundled payments in the commercial market. Am J Manag Care. 2020 10 01; 26(10):e300-e304. PMID: 33094941.

Howell A, Lambert A, Pinkston MM, Blevins CE, Hayaki J, Herman DS, Moitra E, Stein MD, Kim HN. Sustained Sobriety: A Qualitative Study of Persons with HIV and Chronic Hepatitis C Coinfection and a History of Problematic Drinking. AIDS Behav. 2020 Oct 16. PMID: 33064248.

Huberfeld N, Watson S, Barkoff A. Struggle for the Soul of Medicaid. J Law Med Ethics. 2020 09; 48(3):429-433. PMID: 33021181.

Kim W, Krause K, Zimmerman Z, Outterson K. Improving data sharing to increase the efficiency of antibiotic R&D. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020 Oct 23. PMID: 33097914.

Merker VL, Plotkin SR, Charns MP, Meterko M, Jordan JT, Elwy AR. Effective provider-patient communication of a rare disease diagnosis: A qualitative study of people diagnosed with schwannomatosis. Patient Educ Couns. 2020 Sep 28. PMID: 33051127.

Minegishi T, Young GJ, Madison KM, Pizer SD. Regional market factors and patient experience in primary care. Am J Manag Care. 2020 10; 26(10):438-443. PMID: 33094939.

Oberlander J, Singer PM, Jones DK. Can the Elections End the Health Reform Stalemate? N Engl J Med. 2020 Oct 22; 383(17):1601-1603. PMID: 33085858.

Schonbrun YC, Anderson BJ, Johnson JE, Kurth M, Timko C, Stein MD. Barriers to Entry into 12-Step Mutual Help Groups among Justice-Involved Women with Alcohol Use Disorders. Alcohol Treat Q. 2019; 37(1):25-42. PMID: 32982031.

Stein MD, Herman DS, Kim HN, Howell A, Lambert A, Madden S, Moitra E, Blevins CE, Anderson BJ, Taylor LE, Pinkston MM. A Randomized Trial Comparing Brief Advice and Motivational Interviewing for Persons with HIV-HCV Co-infection Who Drink Alcohol. AIDS Behav. 2020 Oct 12. PMID: 33047258.

Woodrell CD, Goldstein NE, Moreno JR, Schiano TD, Schwartz ME, Garrido MM. Inpatient Specialty-Level Palliative Care Is Delivered Late in the Course of Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Associated With Lower Hazard of Hospital Readmission. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020 Oct 06. PMID: 33035651.

The post Recent publications from Boston University’s Department of Health Law, Policy and Management: January 2021 Edition first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

Raising the minimum wage and public health

The federal minimum wage in the United States has remained at $7.25 since 2009, although some states have since set a higher rate. But the national debate about a minimum wage increase has begun again. President Biden’s economic stimulus package calls for an increase to $15 an hour and Congress re-introduced the 2019 Raise the Wage Act earlier this week.

Raising the minimum wage could have substantial public health benefits, but it’s unwise to assume they would be felt universally. What does the research say about the potential effects on different sub-populations? It turns out, not much.

In JAMA Health Forum, Austin Frakt and I go into more detail. You can read the full piece here!

The post Raising the minimum wage and public health first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

January 27, 2021

Cancer Journal: WTF, I have a lung tumour?

The Cancer Journal is the story of my experience as a throat cancer patient during the COVID-19 pandemic. I finished my radiation sessions back on September 18, 2021. Well, I hear you ask, are you cured?

Before treatment started, I had imagined that I would get a regular computerized tomography (CT) scan. But my first follow-up CT was scheduled for December 21, 2020, almost 10 weeks after my last radiation session. It turns out that it is not as easy as you’d think to determine whether radiation is succeeding in destroying a tumour. The reason is that radiation traumatizes your flesh, leaving it burned and swollen. It’s meant to kill the tumour while not quite killing the tissue surrounding it. The problem is that the swelling of the burned tissue makes CT images difficult to read. So you have to wait for the flesh to cool before you take the image.

December 21 came, finally, and I had the image taken. I didn’t hear anything for a considerable time. But, first, it was the holidays, and second, COVID has put exceptional stress on provincial hospitals. So I get it: this is not a time when you can expect quick responses.

On January 11, the CT report appeared in MyChart, the patient portal to the hospital’s electronic health record (EHR) system.

The login page for MyChart, the patient portal to the EHR at my hospital.

Here’s how the report begins:

CT SCAN OF THE NECK

CLINICAL HISTORY: base of tongue cancer post XRT [x-ray therapy] response…

COMPARISON: Compared to prior CT dated July 3, 2020.

TECHNIQUE: 2.5 mm helical sections through the neck with administration of intravenous contrast.

FINDINGS: There is [sic] extensive posttreatment changes noted in the neck soft tissue. There is almost complete resolution of the primary right lung base tumor with small residual hyperdense area measuring 10 x 12 mm…

Wait a freaking minute. Let’s read that again.

There is almost complete resolution of the primary right lung base tumor…

I’ve been in treatment for throat cancer. Who said anything about a LUNG tumour? But the report referred twice to a lung tumour.

(By the way, the above was how I reacted to this report. My wife’s reaction — she is a physician — triggered seismographs across Eastern Canada. In a few years, alien astrophysicists on nearby stars will be perplexed by tremors in the fabric of space-time that register in their gravitational wave detectors.)

I wrote and called my oncologist. No response. Eventually, I called Patient Relations, the people who used to be called Patient Advocates. They got hold of the radiologist who had read the image. He was, the patient advocate told me, deeply sorry. He saw a residual tumour mass in my tongue and throat. Apparently, the speech recognition application that transcribed his dictated report misheard ‘lung’ for ‘tongue.’ I do not have a lung tumour.

A day later, I got a call from my oncologist. He, too, apologized. When read correctly, the CT was mostly positive, although it was not clear enough to rule out residual cancer. He promised to schedule a positron emission tomography (PET) scan to understand better whether the remaining tumour is dead, or alive and still dangerous.

What can we learn from this misadventure? It confirmed my impression that the health care system has yet to establish an effective way for caregivers and patients to communicate except through in-person, video, or telephonic visits. I’ve not been successful in getting questions answered using the Cancer Centre’s Patient Support Line. And so far, MyChart has mostly wasted my time or misled me.

However, global criticisms like the ones I just made in the last paragraph aren’t that helpful. Part of the process of building an effective caregiver-patient communication system is identifying specific problems and fixing them. How do we do this?

First, let’s acknowledge that the mistranscription of my CT report was a significant error. It stressed the hell out of us and, worse, it might have misled a caregiver who needed to learn about my health from my EHR.

But errors happen, and a ‘lung’ for ‘tongue’ confusion is understandable. One can assume that continued progress in speech recognition will reduce these errors. But we have to expect errors and given that, what processes can be put in place to catch them?

There’s a literature on transcription errors in radiologic reports and an even larger one concerning medication errors in prescriptions. I hope that these literatures describe ways to prevent and correct errors that do not force radiologists or oncologists to spend additional time on documentation. Nor do I think that hiring scores of human proofreaders is a solution that would scale.

The long-term solution may be an automated system that can efficiently screen medical communications for logical coherence and consistency with data in the EHR. I’m struck that when I read my CT report, I saw immediately that the reference to ‘lung’ was anomalous. If a layperson can see an anomaly, could we train an AI to catch one? Don’t dismiss the thought. I certainly don’t want a robot that autocorrects CT reports. But I do want one that can register surprise when something unexpected happens.

To read my Cancer Posts from the start, please begin here.

The post Cancer Journal: WTF, I have a lung tumour? first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

January 22, 2021

Shkreli Awards: Profiteering and Dysfunction in US Healthcare

Last year we did an episode on the third annual Shkreli Awards from the Lown Institute – ten examples of profiteering and dysfunction in healthcare. The ins and outs of the healthcare system are the bread and butter of this channel, so we were more than happy to dedicate another episode to the fourth annual Shkreli Awards, and this year’s did not (or did?) disappoint.

The post Shkreli Awards: Profiteering and Dysfunction in US Healthcare first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers