Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 135

May 22, 2017

Taking the Nuclear Option Off the Table

Last Thursday, fifteen states and the District of Columbia moved to intervene in House v. Price, the case about the ACA’s cost-sharing reductions. At the same time, they asked the court to hear the case promptly.

This is a bigger deal than it may seem, and could offer some comfort to insurers that are in desperate need of it. Apologies for the long post, but the law here is complex and uncertain.

* * *

When the House of Representatives sued the Obama administration a few years back, it argued that Congress never appropriated the money to make cost-sharing payments. The district court sided with the House and entered an injunction prohibiting the payments. The court, however, puts its injunction on hold to allow for an appeal.

The Trump administration has now inherited the lawsuit, and the health-care industry is waiting on tenterhooks to see what it will do. For now, the case has been put on hold. But if Trump drops the appeal, which he has threatened to do, the injunction would spring into effect and the cost-sharing payments would cease immediately, destabilizing insurance markets across the country. It’s the nuclear option.

If the states are allowed to intervene, however, they could pursue the appeal even if Trump decides to drop it. With the appeal in place, the injunction couldn’t take effect until the case is heard and decided.

What’s more, the states are very likely to prevail. Not on the merits: as I’ve written before, the House is right that there’s no appropriation to make the cost-sharing payments. But the D.C. Circuit is likely to be skeptical of the district court’s conclusion that the House of Representatives has standing to sue. That’s why the states want to court to decide the case quickly: they hope to get rid of the lawsuit once and for all.

Allowing the states to intervene would not eliminate uncertainty. The D.C. Circuit could always surprise us and affirm the district court’s decision. Premiums for 2018 would still have to rise in response to the risk that payments might stop sometime next year. And even if the House loses, the Trump administration might be tempted to stop making the payments anyhow—although it’s not clear that it has the legal authority to do so without going through the cumbersome process of withdrawing an Obama-era rule.

Still, insurers could breathe a bit easier. If the states are allowed to intervene, Trump couldn’t blow up the individual markets in a fit of pique.

* * *

So can the states intervene? It’s tricky. The states think they meet the typical standard for intervening: they have an interest in the outcome of the proceedings (check), the parties don’t adequately represent their interests (check), and their motion is timely (more on that in a moment).

But the states are playing a little fast and loose. They’ve invoked the standard for intervening in the district court pursuant to Rule 24 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. There’s no equivalent rule governing appeals (with a narrow exception not applicable here).

This may seem like a technical point. It’s not. If you want to participate in a lawsuit that’s already been filed, it’s your responsibility to intervene as soon as possible. If you wait until there’s an appeal, you’ve typically waited too long: As the D.C. Circuit has explained, “[i]t would be entirely unfair, and an inexcusable waste of judicial resources, to allow a potential intervenor to lay in wait until after the parties … have incurred the full burden of litigation before deciding whether to participate in the judicial proceedings.”

* * *

But there are exceptions to every rule. As one of the leading procedural treatises says, intervening on appeal is “permitted in various circumstances that do not seem to threaten either the parties or orderly judicial process.” Because it happens so rarely, however, there aren’t well-developed rules about whether to allow intervention on appeal.

So let’s return to first principles. The idea behind intervention is that the courts shouldn’t decide cases that affect the rights of third parties without giving those parties a chance to be heard. At the same time, litigation would be a nightmare if every Tom, Dick, and Harry could throw his hat into the ring.

Courts try to strike a balance. They insist that third parties intervene as early as possible. They also don’t allow intervention if someone who’s already a party can be counted on to represent the third party’s interest.

That’s why the states couldn’t have intervened when the case was before the district court. The Obama administration was vigorously defending the constitutionality of the cost-sharing reductions, much as the states would have done. Their interests were aligned. Even after Trump’s election, it looked like the Justice Department would keep defending the payments—which is perhaps why an earlier effort to intervene in House v. Price was rebuffed.

Matters are very different today. Cementing his reputation as the world’s worst client, President Trump has publicly toyed with the idea of cutting off the cost-sharing reductions in an effort to force concessions from Democrats. His Attorney General has said that House’s claim “has validity.” Indeed, Politico reported late last week that Trump, over his adviser’s objections, wants to stop the payments altogether.

At this point, it’s nuts to think the states can count on the Trump administration to represent their interests. Those interests, moreover, are pretty clearly sufficient to give them constitutional standing to participate. Without the cost-sharing payments, millions of their residents could lose coverage, and they’d have to cover some of the health-care costs of the newly uninsured.

* * *

Maybe this is the rare case, then, where late intervention is both necessary and appropriate. There’s an intriguing analogy here to Warren v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, where the Ninth Circuit had asked Erwin Chemerinsky, a prominent constitutional law scholar, to submit an amicus brief on a tricky question implicating the Free Exercise Clause. Before the Ninth Circuit decided the case, however, the parties settled and moved to dismiss the appeal. To forestall that dismissal, Chemerinsky tried to intervene—much as the states are trying to do here.

The Ninth Circuit said no, but not because it believed that appellate intervention was categorically inappropriate. It reasoned, instead, that Chemerinsky wanted to introduce a new issue into the litigation (bad) and that he could always file a separate lawsuit to protect his interests.

Neither factor is present in House v. Price, however. The states aren’t trying to introduce a new issue at some late stage. They just want to pick up where the Obama administration left off. Plus, because the district court’s injunction would take immediate effect if the case was dismissed, the states can’t just file their own lawsuit to keep the money flowing. It’s this appeal or nothing.

* * *

In general, there are good reasons to disfavor intervention in a pending appeal. But the D.C. Circuit will allow it “in an exceptional case for imperative reasons.” House v. Price is, in my judgment, one such case.

The change in administration has resulted in an unexpected change in one of the party’s litigating positions. The states haven’t sat on their rights: they’re jumping in at the first available opportunity. And the existence of the injunction means they can’t just file their own lawsuit to protect their interests.

We’ll see if the D.C. Circuit sees matters the same way. But I’ll be watching closely. If the states succeed, they’ll take the nuclear option off the table for the time being. That’d be some welcome news for the beleaguered Affordable Care Act.

May 18, 2017

Why Marathons Are More Dangerous for Nearby Residents Than Runners

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2017, The New York Times Company).

At least 21 runners died in United States marathons from 2000 through 2009, most from heart problems. Seven more died a day later. Those results from a study published in 2012 sound scary, until you consider that this was out of more than 3.7 million participants.

A recent study suggests that the far bigger cardiovascular danger is not faced by runners, but by older people who live in the cities where marathons are occurring and might be delayed from receiving care. For runners, there are always medical personnel on hand to assist them. For spectators, there are always law enforcement workers guarding against terrorist attacks and other threats. But for others, the findings show that we need to think about how big civic events affect the connection between transportation and health care systems.

In the new study, published in The New England Journal of Medicine, researchers looked at the 11 American cities with the biggest marathons from 2002-2012. They gathered data on Medicare patients admitted to a hospital on the day of a marathon, versus the same day of the week five weeks earlier and five weeks later. Then they looked at 30-day mortality — the percent of people admitted to a hospital who died in that period — for those patients who were admitted with acute myocardial infarction or cardiac arrest.

What they found was concerning. Patients admitted on a marathon day had a 28.2 percent chance of dying within 30 days. The rate for those admitted on nonmarathon days was 24.7. That’s a significant absolute difference, as well as a large relative one.

The people admitted on marathon and nonmarathon days were the same with respect to age, race, sex and their chronic conditions. The hospital admission volume was the same, too. None of the people were actually running in the marathon. There weren’t a lot of out-of-town admissions, either.

Although the miles driven by ambulances were the same on all days, the transport times were 4.5 minutes longer while the roads were closed for the race. Some transports were very long because of road congestion. Further, many patients drove themselves to the hospital, and they might have seen even bigger delays than ambulances.

“Marathons and other large, popular civic events are such an important part of the fabric of life in our big cities,” said Dr. Anupam Jena, associate professor at Harvard Medical School and lead author of the N.E.J.M. study. “But the organizers of these events need to take these risks to heart when they are planning their events, and find better ways to make sure that the race’s neighbors are able to receive the lifesaving care that they need quickly.”

I’ve written in the past about how emergency personnel who administer advanced life support may not be providing any benefit above basic life support. That shouldn’t lead anyone to think that basic life support isn’t miraculous.

When people receive CPR from emergency personnel outside the hospital for cardiac arrest, their 30-day survival rate doubles. Even in the hospital, a patient who experiences a delay in getting defibrillation of about one minute has almost a 20 percent absolute decrease in surviving to the point of a hospital discharge.

But the time it takes to get to the hospital is critical as well. In fact, one of the reasons that researchers say basic life support may be as good as, if not better than, advanced life support is that the shorter and simpler protocols lessen the time spent in the field and reduce the time it takes an ambulance to get someone to the hospital. Better emergency response times are often cited as one of the main reasons that the rate of heart disease deaths has continued to drop in the United States.

Too few Americans are trained in CPR or know where to find an automated external defibrillator. Defibrillators have become so easy to use that almost anyone can do it. Patients who have cardiac arrest but who get rapid CPR and defibrillation can double their chance of survival.

Each minute of delay decreases the chance of survival by up to 10 percent. It’s bad enough that events like marathons can delay the time it takes emergency personnel to get to a victim. Those stuck in cars have almost no access to lifesaving interventions.

We devote a significant amount of time worrying about protecting participants and spectators from disruptive events in our cities. It may be that we need to spend just as much, if not more, time worrying about everyone else.

@aaronecarroll

May 16, 2017

Post-acute care: Medicare Advantage vs. traditional Medicare

From a public spending point of view, post-acute care is particularly problematic. Most of Medicare’s geographic spending variation is due to this type of care. Part of the story is that Medicare pays for post-acute care in several different ways, with different implications for efficiency.

For example, traditional Medicare (TM) — which spends ten percent of its total on post-acute care — pays skilled nursing facilities per diem rates but inpatient rehabilitation facilities a single payment per discharge. Post-acute care is also available through Medicare Advantage (MA), which operates under a global, per-enrollee, payment. Unlike TM, MA plans establish networks, may require prior authorization for post-acute care, and can charge more in cost-sharing for post-acute care than TM does.

These different payment models offer different incentives that may affect who receives care, in what setting, and for how long. In Health Affairs, Peter Huckfeldt, José Escarce, Brendan Rabideau, Pinar Karaca-Mandic, and Neeraj Sood assessed some of the consequences of those incentives. Focusing on hospital discharges for lower extremity joint replacement, stroke, and heart failure patients between January 2011 and June 2013, they examined subsequent admissions to skilled nursing and inpatient rehabilitation facilities, comparing admission rates, lengths of stays, hospital readmission rates, time spent in the community, and mortality for MA and TM enrollees. To do so, they used CMS data on post-acute patient assessments for patients with discharges from hospitals that received disproportionate share or medical education payments from Medicare.

You might be wondering how the investigators could possibly study MA patients with CMS data. First of all, post-acute facilities are required to file patient assessments for all patients, MA and TM alike. Second, in order to pay disproportionate share and medical education payments to hospitals, CMS collects “information only” (i.e., zero charge) claims for MA patients from hospitals entitled to those payments. Such hospitals account for 92 percent of Medicare discharges. (As far as I know, validation analyses of information only claims has not been published.)

Their analytic file included almost one million lower extremity joint replacement episodes, almost a half-million stroke episodes, and just over three-quarters of a million heart failure episodes. About a quarter of these were for MA patients. Their analyses adjusted for patient characteristics and used hospital fixed effects.

Lower extremity joint replacement MA patents were two percentage points more likely to be admitted to a skilled nursing facility than TM patients, but an MA patient stayed 3.2 fewer days, on average. On the other hand, lower extremity joint replacement MA patients were far less likely to be admitted to an inpatient rehabilitation facility than TM patients — an adjusted difference of 6.4 percentage points. Lengths of stay were about the same.

Findings for stroke patients were similar. TM heart failure patients were slightly more likely to be admitted to a skilled nursing facility than MA patients, and stayed 1.7 days longer than MA patients. The trend is similar for heart failure patient admissions and stays at inpatient rehabilitation facilities, but the overall rates of admission to them is very low for these patients.

MA patients of all types were less likely to be readmitted to the hospital and more likely to be living in the community than TM patients. There were no statistically significant mortality differences. These results suggest that MA patients are not adversely affected by their lower volume of post-acute care utilization.

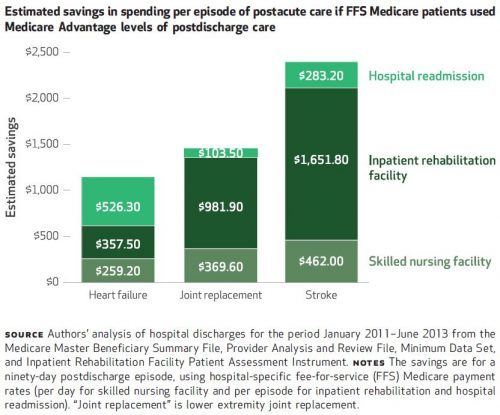

If TM patients were to somehow adopt the same level of utilization of post-acute care as MA patients, the program would save money. Results of the authors’ savings calculations, by condition, are shown in the following chart. Overall, they represent about a 16 percent reduction in spending.

One way TM is progressing toward more efficient post-acute spending is through accountable care organizations (ACOs). That’s according to a recent paper by J. Michael McWilliams and colleagues. They found, for example, that ACOs that entered the Medicare Shared Savings Program in 2012 reduced post-acute spending by 9% without reductions in quality of care (as measured by mortality, readmissions, and use of highly rated skilled nursing facilities), relative to non-ACO providers.

Naturally, there are some limitations to the Huckfeldt et al. analysis. First, though the authors did not detect any favorable selection into MA, it is possible that MA patients differ systematically from TM patients such that the results are not completely driven by MA care management. Second, the study did not examine every type of post-acute care — home health care, long-term hospital care, or other outpatient care were omitted from the analysis. Home health care is less costly than the types of care examined. Long-term hospital care is relatively rare. And, outpatient care is unobservable for MA. Third, there are other, possible measures of quality of care besides those examined (readmissions, time in the community, and mortality).

All told, the results suggest that MA manages post-acute care more tightly than TM and with no observed, negative consequences for patients.

May 15, 2017

Healthcare Triage: Healthcare and Customer Satisfaction – Not ALWAYS Mutually Exclusive

You’ve all experienced it: There’s a problem with your health care bill, or you have difficulty getting coverage for the care you need. Your doctor or hospital tells you to talk to your insurer. Your insurer tells you to talk to your doctor or hospital. You’re stuck in an endless runaround.

A small patient advocacy industry has sprung up to help, but that help can cost several hundred dollars an hour. Is there a way to get the customer service we deserve? That’s the topic of this week’s Healthcare Triage.

Special thanks to Austin, from whose Upshot column this episode was adapted. Links to further reading and sources can be found there.

Risk adjustment cannot solve all selection issues—network contracting edition

In our Hamilton Project paper, Nicholas Bagley, Amitabh Chandra, and I explain why a health insurance market in which plans compete on cost effectiveness won’t work. (Click through, download the PDF, and read Box 2 on page 9, titled “Why Health Plans Cannot Differentiate on Coverage.”)

The recent NBER paper by Mark Shepard makes the same argument we made, but to illustrate problems in hospital markets with heterogeneous preferences for costly, star hospitals. Some key quotes from Mark’s paper:

But even excellent risk adjustment is unlikely to offset costs arising from preferences for using star (or other expensive) providers. These preferences create residual cost variation that can lead to a breakdown of risk adjustment (Glazer and McGuire 2000). Second, the two channels may have different cost and welfare implications. While sickness makes individuals costly in any plan, preferences for a star hospital only make enrollees costly if a plan covers that star hospital. Stated differently, preferences affect how much an individual’s costs increase when their plan adds coverage of the star hospital. […]

My results suggest that consumer preferences for high-cost treatment options – star hospitals in my study, but the same idea could apply to any expensive provider, drug, or treatment – can naturally lead to adverse selection, and specifically selection on moral hazard. […]

In the current system, consumers get access to star hospitals based on their plan choice, after which use of these providers is highly subsidized by the insurer. This setup leads to higher costs (moral hazard) and selection on moral hazard. Policies that reduce this moral hazard – e.g., higher “tiered” copays for expensive hospitals or incentives for doctors to refer patients more efficiently – may also mitigate the adverse selection. Differential plan prices for different groups may also improve the efficiency of consumer sorting across plans.

Mark’s paper is also noteworthy because it is one of the few to address consequences of network contracting. This is a hard area to study because plans’ hospitals and physician networks are not easily observed. Other good work in this area has been done by my colleagues at the Leonard Davis Institute.

Another day, another cost shifting claim

Via blog post, David Anderson drew my attention to a Health Affairs post by Billy Wynne, the Managing Partner of TRP Health Policy, in which Mr. Wynne wrote, “[C]ommercial rates are hiked, often stratospherically, to compensate for typically insufficient Medicaid reimbursement.”

Normally, I’d have to remind the world that many recent studies find no evidence for this kind of cost shifting. But, David did the work for me (and by citing me), so go read his post if you still don’t know the truth of the matter.

Oh, and spread the word. It’s very hard to keep up with assertions of cost shifting and push back against every one, even with David’s help.

May 11, 2017

Why were there no ‘Harry and Louise’ ads against the AHCA?

The American Health Care Act (AHCA) passed the House in the face of opposition from physicians, hospitals, and insurers. But that opposition was muted and it failed to defeat the bill. This is mysterious because amid other provisions the bill cut more than $800 billion from Medicaid funding. That money would make a real difference for many doctors, hospitals, and Medicaid Managed Care plans (to say nothing of disabled people or poor people currently receiving Medicaid). There’s an explanation for this meek opposition in Robert Pear’s article in the New York Times.

First, let’s revisit how fiercely some of these groups resisted previous health care legislation. It’s often thought that the Health Insurance Association of America’s ‘Harry and Louise’ ad helped defeat the Clinton health care plan of 1993.

So why aren’t these interest groups on the barricades this time? One reason, as Pear explains, is that no one in the Senate takes the House bill seriously.

Reince Priebus, the White House chief of staff, has said he expects the Senate to make improvements in the repeal bill that the House passed last week… But senators have gone much further: The Senate is starting from scratch.

“Let’s face it,” Senator Orrin G. Hatch of Utah, chairman of the Finance Committee, said Monday. “The House bill isn’t going to pass over here.’’

Hospital executives, among the most outspoken critics of the House bill, are in town for the annual meeting of the American Hospital Association and will lobby the Senate this week. Thomas P. Nickels, an executive vice president of the association, predicted that the Senate would produce an “utterly different version” of the legislation.

So that’s why the resistance was muted: the relevant interest groups were told not to worry about what was in the AHCA. The House vote was just for… what? To save the President and Speaker Ryan from the humiliation of being unable to pass anything?

Of course, if the Senate is starting from scratch, it means that the Republicans still have no idea what their design for replacing the ACA is. Moreover, if the Senate does draft new legislation, what is the magic that will make the Senate bill the real bill? Suppose the Senate drafts and passes a significantly more moderate bill. Then that bill, or a House-Senate compromise bill, will have to be passed by the House. What happens to the delicate compromise between conservative members and radically-conservative members that was required to pass the AHCA through the House? Will the Senate bill be dead on arrival at the House?

Healthcare Triage: Patients Don’t Shop Around, Even When They Can

You probably know where to pump the cheapest gas and how to get price comparisons online in seconds for headphones and cars. But how would you find the best deal on an M.R.I. or a knee replacement? No idea, right?

And if we could, it would be the magic fix for health care, right? Yeah… not so much. That’s the topic of this week’s Healthcare Triage.

Special thanks to Austin, who wrote the Upshot column from which this episode was adapted.

May 10, 2017

Some Medicare prescription drug plans cost more than we think

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2017, The New York Times Company).

Many studies have demonstrated what economics theory tells us must be true: When consumers have to pay more for their prescriptions, they take fewer drugs. That can be a big problem.

For some conditions — diabetes and asthma, to name a few — certain drugs are necessary to avoid more costly care, like hospitalizations. This simple principle gives rise to a little-recognized problem with Medicare’s prescription drug benefit.

For sicker Medicare beneficiaries, the Harvard economist Amitabh Chandra and colleagues found, increased Medicare hospital spending exceeded any savings from reduced drug prescriptions and doctor’s visits. Consider patients who need a drug but skip it because they feel the co-payment is too high. This could increase hospitalizations and their costs, which would make them worse off than if they’d selected a higher-premium plan with a lower co-payment.

Though just a simplified example, this is analogous to what Medicare stand-alone prescription drug plans do. They achieve lower premiums by raising co-payments. This acts to discourage the use of drugs that would help protect against other, more disruptive and serious health care use, like hospitalization.

Studies show that insurers, many of which are for-profit companies after all, are using such incentives to dissuade high-cost patients from enrolling or using the benefit. There’s evidence this occurs for Medicare’s drug benefit, as well as in the Affordable Care Act’s marketplaces.

The most popular type of Medicare drug coverage is through a stand-alone prescription drug plan. A stand-alone plan never has to pay for hospital or physician visits — those are covered by traditional Medicare. Another way to get drug benefits from Medicare is through a Medicare Advantage plan that also covers those other forms of health care and is subsidized by the government to do so.

Because of this difference, stand-alone drug plans are less invested than Medicare Advantage plans in keeping people healthy enough to avoid some hospital visits.

A study by the economists Kurt Lavetti, of Ohio State University, and Kosali Simon, of Indiana University, quantifies the cost. Compared with Medicare Advantage plans, stand-alone drug plans charge enrollees about 13 percent more in cost sharing for drugs that are highly likely to help patients avoid an adverse health event within two months. They charge up to 6 percent more for drugs that help avoid adverse health events within a year.

It’s not as if stingier insurers are more likely to offer stand-alone plans than Medicare Advantage plans. Even among plans owned by the same insurer, Medicare Advantage plans are more generous in covering these kinds of drugs than stand-alone drug plans. (These differences are apparent only on average. In some instances, stand-alone drug plans offer better deals.)

Of course, people have choices about plans. Those who have selected a stand-alone drug plan, as opposed to a Medicare Advantage plan, have done so voluntarily. Why do some make this choice?

One answer is that some people are not comfortable with the more narrow networks Medicare Advantage plans offer, with their fewer choices of doctors and hospitals. By choosing a stand-alone drug plan, they can remain in traditional Medicare, which has an open network.

In addition, consumers are generally more attracted to lower-premium plans than higher ones, even if the difference is exactly made up in co-payments. This may be because premiums are easier to understand than cost sharing. Moreover, premiums reflect a sure loss — you must pay the premium to remain in the plan. A higher co-payment, on the other hand, won’t necessarily lead to a loss because you may not use a service.

The appeal of lower premiums is an incentive for stand-alone drug plans to reduce them and increase co-payments. But that can dissuade those who need medications from filling prescriptions and taking them.

Part of the purpose of Medicare’s drug benefit is to encourage enrollees to take prescription drugs that can keep them out of the hospital. In July 2003, promoting the legislation that created Medicare’s drug benefit, President George W. Bush articulated this point. “Drug coverage under Medicare will allow seniors to replace more expensive surgeries and hospitalizations with less expensive prescription medicine,” he said.

But the design of Medicare’s drug benefit includes stand-alone plans that aren’t liable for hospital costs, so they don’t work as hard to avoid them. Encouraging more beneficiaries into comprehensive plans — through Medicare Advantage — or offering a drug plan as part of traditional Medicare itself would address this limitation.

Postscript: A CMMI initiative that started this year in five regions is designed to create incentives for stand alone PDPs to reduce non-drug Medicare expenditures.

May 9, 2017

Amgen’s Money-Back Guarantee: Simply Too Good To Be True

The following is a guest post by Rodney Hayward, Director of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars, and the National Clinician Scholars at IHPI. He’s a Professor of Medicine and Public Health at the University of Michigan. Follow him on Twitter at @ProfHayward.

Multiple small clinical trials suggested that PCSK9is (a new class of cholesterol-lowering medications) might be the next super drug-class. These early trials suggested that PCSK9is dramatically decreased cardiovascular disease (CVD) events (strokes and heart attacks) in those who had very high CVD risk and could not take statins (the current standard for treating cholesterol).

But most people with very high CVD risk tolerate statins just fine, greatly limiting the market for PCSK9is. A potential solution was to prove that the drugs worked better even for those on statins already. Unfortunately for the main PCSK9i manufacturer (Amgen), the first large randomized trial examining PCKS9-abs benefits in those on statins was highly disappointing. In the much larger market of high CVD risk people on statins, the relative reduction in non-fatal CVD events was much less than expected (25%) with no effect on mortality.

Although no one wants to have a heart attack or stroke, the lack of a mortality benefit – and the ~$14,500/yr price tag – led most to conclude that the expense was not worth the gain. Some pundits called for a price cut, but last week Amgen came up with a better idea – a full Money-Back Guarantee!

What A Deal!

In response to their falling stock price, Amgen announced last week that they would refund the cost of the drug in full if an individual taking it regularly has a major CVD event. This was portrayed by some media sources as an advance for pay-for-performance, and it certainly makes great intuitive sense. Yes, it may be a small consolation if the PCSK9i didn’t prevent your stroke, but “you get your money back if the medication doesn’t work for you.”

The problem is that the italicized sales pitch above is completely untrue.

What A Scam!

Modern psychology has demonstrated that we humans are terrible intuitive statisticians and that it’s quite easy to fool us with statistical illusions. So let’s briefly go through the math to understand why Amgen’s sales pitch is untrue.

A Best-case Scenario: A sizable group (though a small proportion of all adults) continues to be at very high CVD risk (~5% 5-year risk) after taking a statin, a daily aspirin, and blood pressure medications as indicated (cost ≈ $30-$150/yr). If you give a PCSK9i to 1000 such individuals, current evidence suggests that you would prevent, on average, 12 to 13 non-fatal CVD events over a five year period (0.05 [5-year risk] * 0.25 [PCKS9i’s relative risk reduction] = 0.0125 = 12.5 in 1000) at a cost of ~$72.5 million. We know that more than 30% of these events will be quite minor, but let’s ignore that so as to not be accused of nitpicking. Over 5 years, Amgen would need to return ~$1.4 million to ~37.5 of the 1000 people (2.5yrs [average years to CVD event in the 5-year period] * $14,500/yr * 37.5 [number of people who had a CVD event) ≈ $1.4 million).

But if only 12 to 13 people in 1000 benefited and only 37 to 38 people received refunds, who are the remaining 950 people who did not benefit? They are the 95% of people who were not destined to have a heart attack or stroke regardless.

So the claim, “If the PCSK9i doesn’t work for you, you get your money back!” is a complete scam. Over 98% (950 of ~962.5) of those who did not have a stroke or heart attack over 5-years received no benefit from the PCSK9i because they were not destined to have a CVD event regardless of treatment.

Ironically, the less likely a person is to benefit from the PCSK9i (ie, the lower their CVD risk), the less likely Amgen will need to refund their money.

So let’s restate Amgen’s Money-Back guarantee more accurately.

Individual Perspective: If you are a very high CVD risk person on a statin and you take a PCSK9i for five years, you have about a 1.25% chance of avoiding a non-fatal heart attack or stroke at a cost of ~$70,000, about a 3.75% chance of having a stroke or heart attack and getting your money back, and about a 95% chance of paying ~$70,000 and receiving no benefit.

Payer’s Perspective: For every 1000 high CVD risk beneficiaries on statins, paying for a PCSK9i for 5 years will prevent 12-13 non-fatal heart attacks or strokes, on average, and Amgen has generously offered to reduce the price to you by ~ 3.75%, from ~$72.5 million to ~$70 million.

Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers