Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 134

June 5, 2017

Healthcare Triage: The Mysteries of the Microbiome: There’s Still a Lot to Learn

While we have long known about the existence of microbes — the tiny bacteria, fungi and archaea that live all around, on and in us — our full relationship has become one of the hottest topics for research only in recent years. That’s the topic of this week’s Healthcare Triage.

This episode was adapted from a column I wrote for the Upshot. Links to resources and further reading can be found there.

June 2, 2017

Healthcare Triage News: Knee Surgery Doesn’t Improve Outcomes, but We Still Do A LOT of Them

The news tells us that arthroscopic surgery for knee arthritis and meniscal tears isn’t worth it. Healthcare Triage told you that a while ago. What’s new? This is Healthcare Triage News.

Read more here and here and here.

Moral convictions and the contraception exemptions

The Trump administration’s draft contraception rule would not only allow employers to drop contraception coverage for religious reasons. It would also allow employers who have moral objections to do the same.

That gives rise to a puzzle. The lawsuits over the contraception mandate have focused on the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), which requires the federal government to avoid placing burden on the exercise of religion. It’s RFRA that gives HHS the power to craft a religious exemption for contraception coverage.

RFRA, however, does not extend to moral objections without a basis religious exercise. As such, RFRA can’t supply authority for HHS to exempt employers with moral objections to the contraception mandate.

So where does the agency find that authority? HHS points to section 2713(a)(4) of the Public Health Service Act, which is codified here:

A group health plan and a health insurance issuer offering group or individual health insurance coverage shall, at a minimum provide coverage for and shall not impose any cost sharing requirements for …

(4) with respect to women, such additional preventive care and screenings [beyond those rated “A” or “B”] as provided for in comprehensive guidelines supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration for purposes of this paragraph.

Does that look to you like it allows HHS to craft exemptions due to moral objections? Me neither.

The agency sees things differently. Employer and insurer obligations, HHS says, are confined to what’s “provided for in comprehensive guidelines,” and the statute doesn’t say what those guidelines should cover. “Unlike other provisions in section 2713, section 2713(a)(4) does not require that the guidelines be ‘evidence-based’ or ‘evidence-informed.’” As such, “to the extent the [guidelines] do not provide for or support the application of such coverage to exempt entities, the ACA does not require the coverage.”

In other words, HHS can exempt whoever it wants, for whatever evidence-free reason it wants. Just write the exemption into the guidelines.

I don’t think this is a reasonable interpretation of the statute. The guidelines are supposed to elucidate the “additional preventive care and screenings” that must be covered. That’s why Congress enlisted the help of the Health Resources and Services Administration. It’s a health agency, one that “work[s] to improve the health of needy people.” HRSA knows a lot about preventive services and screenings. HRSA isn’t equipped to decide when moral concerns are sufficiently grave as to require an exemption from a generally applicable law.

To sharpen the point, consider the following statute: “All cars must have seatbelts that meet certain specifications, including any additional specifications as provided for in guidelines drafted by the Seatbelt Safety Administration.” If the agency exempted red cars from its guidelines, that wouldn’t be an exercise of its delegated authority to write safety guidelines. It would be revising Congress’s judgment that “[a]ll cars”—red and blue and gray alike—must have safe seatbelts.

That’s what’s happening here. HHS isn’t specifying the services that employers and insurers are obliged to cover. It’s saying that everyone who objects on moral grounds—all those red cars—are exempted. That’s not a plausible interpretation of the statute. Fairly read, it allows HHS to say what gets covered, not who has to cover it.

Yes, it’s true that Congress didn’t prohibit the guidelines from including moral exemptions. But so what? As the D.C. Circuit has said, “the notion that an agency interpretation is permissible just because the statute in question does not expressly negate the existence of a claimed administrative power (i.e. when the statute is not written in ‘thou shalt not’ terms), is both flatly unfaithful to the principles of administrative law. . . and refuted by precedent.”

The right question, instead, is whether the statute can reasonably be read to have delegated to a health agency the freewheeling power to relieve entities of their responsibility to follow the law. And I just don’t see it.

Now, I don’t know how much of a practical difference the moral exemption will make. HHS thinks that “very few moral nonreligious objectors will adopt a view opposing coverage.” Maybe that’s right, maybe it’s not—HHS has no real way of knowing.

Either way, though, what sense does it make to push a weak legal theory that potentially imperils the whole rule? Once again, it looks like HHS is begging for a lawsuit.

June 1, 2017

The new contraception rule is procedurally flawed

Yesterday, Dylan Scott and Sarah Kliff at Vox got their hands on a leaked version of a draft rule from HHS that, if adopted, would make it much easier for employers to drop contraception coverage for their employees. The rule is under review at the Office of Management and Budget; it could be approved any day.

Whatever the merits of the draft rule, I’m baffled by a procedural move. It’s styled an “interim final rule,” which means that it will take effect the moment it’s published. And, as David Anderson has explained, it’ll only take a hot minute for employers who wish to take advantage of the expanded accommodation to adjust their offerings. So if you’re thinking about getting an IUD, now might be a good time to get one.

The Administrative Procedure Act, however, requires new legislative rules to go through notice and comment before they’re adopted. It’s a cumbersome process, often taking a year or more, but it’s not optional. So what’s HHS’s justification for skipping notice and comment here?

The agency offers two rationales, neither of which is convincing. First, the agency says that it has statutory authorization—specifically, in 26 U.S.C. §9833, 29 U.S.C. §1191c, and 42 U.S.C. §300gg-92—to skip notice and comment. (This isn’t an original claim; Obama’s HHS made it too.) But these provisions are just generic grants of rulemaking authority. They allow the Secretary to “promulgate such regulations as may be necessary or appropriate to carry out” his various responsibilities, including “any interim final rules as the Secretary determines are appropriate.”

None of these laws relieve the Secretary of his responsibility to follow the APA, and the courts don’t read generic grants of rulemaking power to displace the APA’s background rules. If Congress had really meant to license the Secretary to ignore public participation whenever he wanted to, it would have spoken much more clearly. So yes, the Secretary can issue regulations, even interim final regulations, but only when he acts consistently with the APA.

Second, HHS says it has “good cause” under the APA to skip notice and comment. Good cause exists when notice and comment is “impracticable, unnecessary, or contrary to the public interest.” That’s a flexible standard, but the courts have said that it “is to be narrowly construed and only reluctantly countenanced,” with its use “limited to emergency situations.”

So what’s the emergency here? HHS’s explanation is a bit disjointed, but it points out that Obama’s HHS also issued two interim final rules relating to the contraception mandate. Now, that’s true—but only because the agency faced a tight statutory deadline and, later, a Supreme Court order in Wheaton College requiring a rule change. Those are classic reasons to find good cause. Indeed, that’s why the D.C. Circuit brushed back an earlier challenge to one of HHS’s interim final rules: “the modifications made in the interim final regulations are minor, meant only to ‘augment current regulations in light of the Supreme Court’s … order.’”

Here, there’s no deadline and no court order requiring a rule change. (Although the Supreme Court exhorted HHS and religious organizations to resolve their differences in Zubik v. Burwell, that’s not the same thing.) What’s more, the Obama administration did invite feedback before it initially adopted its religious accommodation— and received more than 400,000 comments in response.

In a twist, Trump’s HHS wants to exploit that deluge of comments, as well as hundreds of thousands of other comments on Obama-era proposals, to justify changing the accommodation without public feedback. “Millions of public comments have already been submitted on the scope of the guidelines,” says HHS, “including the issue of whether to expand the exemptions.”

If this new rule was just a minor tweak of the prior accommodation, HHS’s explanation might hold water. But it isn’t. The rule breaks with prior law in at least three big ways. First, it extends the accommodation any and all organizations, not just to religious nonprofits (like Catholic hospitals and universities) and privately held corporations (like Hobby Lobby). Second, it allows employers to drop contraception coverage without filing federal paperwork, potentially complicating efforts to guarantee alternative coverage for employees. Third, unspecified “moral” objections—not just religious ones—are now enough to justify relieving employers of their statutory obligations under the ACA.

HHS may have received millions of comments about contraception, but it hasn’t received focused feedback on these specific proposals. That’s likely to be a problem in court. The D.C. Circuit, in particular, can be really persnickety when agencies don’t provide adequate notice of a proposed change, even where earlier rounds of notice and comment seem to cover the issue. (I’ve been critical of the case law around good cause, and I have some sympathy with HHS’s position here. But the law is what it is.)

At the end of the day, HHS’s justification boils down to a concern with “delay[ing] the ability of [employers] to avail themselves of the relief afforded by these interim final rules” and “further extending the uncertainty caused by years of litigation and regulatory changes.” But that’s just another way of saying that the rule is so important that it has to be rushed out the door without hearing what the public has to say about it.

That’s not how it works. That’s not how any of this works. Notice and comment always causes the delay of important rules. Notice and comment always extends any existing uncertainty. And yet the APA still requires public feedback. If the administration is really concerned about avoiding protracted litigation, why invite a lawsuit over a procedural question? Where’s the fire?

Risk adjustment in the ACA marketplaces: A success with some important gaps

This post was coauthored by Michael Geruso, Timothy Layton, and Daniel Prinz. Michael Geruso is an Assistant Professor of Economics at the University of Texas at Austin. Timothy Layton is an Assistant Professor of Health Care Policy at Harvard Medical School. Daniel Prinz is a PhD student in Health Policy and Economics at Harvard University.

With so much attention in recent months on potential changes to the ACA’s provisions for Medicaid and consumer subsidies, it is easy to overlook some of the most important innovations introduced into the individual markets by the ACA: risk adjustment and reinsurance. The functioning of risk adjustment and reinsurance are un-sexy, behind the scenes, technical matters, but these regulations are crucial to protecting consumers with pre-existing conditions in a competitive insurance market. Premium discrimination and guaranteed renewability tend to attract the most popular attention in terms of non-discrimination, but enforcing a policy of non-discrimination against the chronically ill would be difficult or impossible without risk adjustment.

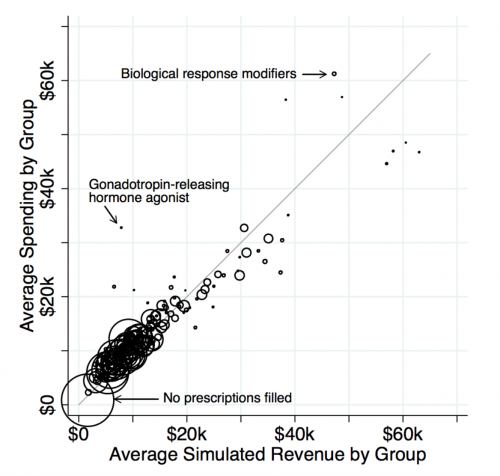

In a recent paper, we evaluate how well risk adjustment and reinsurance perform in eliminating the incentive to avoid sick patients in the ACA Marketplaces. To do so, we look at drug formulary design. If insurers assign certain drugs to high cost sharing tiers, it may be a signal that plans are attempting to avoid the patients who demand those drugs. Using the risk adjustment and reinsurance algorithms from HHS, we simulate profitability at the patient level by subtracting patient claims costs from the simulated revenue (which incorporates premiums plus risk adjustment and reinsurance transfers). We then group patients into categories defined by standard therapeutic classes of drugs. For the vast majority of drug classes, our work shows that risk adjustment and reinsurance neutralize selection incentives: an insurer who attracts this particular group does not benefit or lose disproportionately relative to insurers who avoid the group. This is a big win for the ACA, in that these policies seem to largely counteract one of the primary downsides to bans on premium discrimination: generating large profitability differentials between sick and healthy enrollees.

However, we also show that a few drug classes are still associated with consumer types that exhibit significant unprofitability. This means that an insurer would want to avoid patients who demand these classes of medications.

While this reveals some shortcomings to the ACA risk adjustment system, it also allows us to test an important question: Absent risk adjustment and reinsurance, would insurers actually design drug formularies that are more restrictive for the unprofitable groups? To answer this question, we effectively compare formulary restrictiveness for drugs in classes where costs greatly exceed revenues (the dots far above the 45-degree line in the figure above) to restrictiveness for drugs in classes where costs and revenues match relatively closely (the dots on the 45-degree line).

We find that formularies are much more restrictive for the drugs for which individual-level costs exceed individual-level revenues. This includes drugs treating multiple sclerosis, substance abuse disorders, and infertility in women. The contrast is even sharper for more popular drugs that are likely to be more salient to sick consumers when choosing between plans. The relationship holds even when narrowly comparing classes that differ in net profitability but have similar associated drug and medical costs. (Think of comparing the cost sharing assigned to drug classes within a horizontal slice of the figure.)

What should we take away from this? Detractors of the law have misapplied our findings by asserting that because some patient types are undercompensated by the risk adjustment, the ACA has hurt these groups. There are a number of problems with this argument. First, for this reasoning to be sound individuals taking these drugs would have had to have access to plans with better coverage for these drugs prior to the ACA. This seems unlikely. Many of these individuals have severe chronic conditions that may have disqualified them entirely from purchasing health insurance. Additionally, if they did have access to good coverage for drugs, they were charged exorbitantly high prices for that coverage, generating massive “reclassification risk,” another name for the risk of getting one of these chronic conditions and having your premiums shoot through the roof. Second, this argument ignores the fact that the risk adjustment and reinsurance policies in the ACA in fact seem to be working quite well overall at matching revenues to costs and thereby protecting consumers from the types of perverse contract designs meant to avoid sick consumers.

The takeaway from our study is not that the ACA leads to discriminatory contracts, but that it accomplished the difficult goal of incentivizing insurers to provide high-quality coverage for the vast majority of drug classes. The risk adjustment and reinsurance policies can (and should) be improved to adequately compensate for a small minority of individuals taking drugs in a few outlier classes. The answer is to make the necessary incremental improvements to the policies, not to scrap the ACA entirely with its important and widely popular limits on premium discrimination. As the individual markets continue to evolve, it is important to keep in mind that the only way to guarantee good coverage for the chronically ill is to get the insurer incentives right via tools like reinsurance and risk adjustment.

Even with EHBs and prohibitions on risk-rating, insurers may be able to effectively discriminate through benefit design; furthermore, competition pressures insurers to do this, whether they “want to” or not. If one insurer limits access to an expensive therapy while another chooses to provide easy access to the same drugs, the discriminatory insurer will accrue healthy individuals while the non-discriminatory insurer enrolls more of the sick, driving up its costs—adverse selection potentially leading to a death spiral. Nominally outlawing discrimination could do little in practice to prevent such dynamics. Though risk adjustment doesn’t force insurers to cover services that attract sick enrollees, it makes sick enrollees equally profitable to healthy ones by using transfer payments to decouple health from profitability. For this reason, risk adjustment is ubiquitous in most market settings in the world in which private insurance carriers compete to attract enrollees, including Medicare Parts C and D, and many privatized state Medicaid programs.

As we discuss in other work (here and here), an important part of the incremental improvements may be to revive the reinsurance program in some form, which ended in 2016.

May 31, 2017

Science Needs a Solution for the Temptation of Positive Results

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2017, The New York Times Company)

A few years back, scientists at the biotechnology company Amgen set out to replicate 53 landmark studies that argued for new approaches to treat cancers using both existing and new molecules. They were able to replicate the findings of the original research only 11 percent of the time.

Science has a reproducibility problem. And the ramifications are widespread.

These 53 papers were published in high-profile journals, and the 21 that were published in the highest-impact journals were cited an average of 231 times in subsequent work.

In 2011, Bayer pharmaceuticals reported similar reproduction work. Of the 67 projects they conducted to rerun experiments (47 of which involved cancer), only about 25 percent ended with results in line with the original findings.

It turns out that most pharmaceutical companies run these kinds of in-house validation programs regularly. They seem skeptical of findings in the published literature. Given that their valuable time and their investment of billions of dollars of research resources hinge directly on the success of projects, their concerns seem warranted.

Unfortunately, the rest of us have not been quite so careful. More and more data show we should be. In 2015, researchers reported on their replication of 100 experiments published in 2008 in three prominent psychology journals. Psychology studies don’t usually lead to much money or marketable products, so companies don’t focus on checking their robustness. Yet in this experiment, research results were just as questionable. The findings of the replications matched the original studies only one third to one half of the time, depending on the criteria used to define “similar.”

There are a number of reasons for this crisis. Scientists themselves are somewhat at fault. Research is hard, and rarely perfect. A better understanding of methodology, and the flaws inherent within, might yield more reproducible work.

The research environment, and its incentives, compound the problem. Academics are rewarded professionally when they publish in a high-profile journal. Those journals are more likely to publish new and exciting work. That’s what funders want as well. This means there is an incentive, barely hidden, to achieve new and exciting results in experiments.

Some researchers may be tempted to make sure that they achieve “new and exciting results.” This is fraud. As much as we want to believe it never happens, it does. Clearly, fabricated results are not going to be replicable in follow-up experiments.

But fraud is rare. What happens far more often is much more subtle. Scientists are more likely to try to publish positive results than negative ones. They are driven to conduct experiments in such a way as to make it more likely to achieve positive results. They sometimes measure many outcomes and report only the ones that showed bigger results. Sometimes they change things just enough to get a crucial measure of probability — the p value — down to 0.05 and claim significance. This is known as p-hacking.

How we report on studies can also be a problem. Even some studies reported on by newspapers (like this one) fail to hold up as we might hope.

This year, a study looked at how newspapers reported on research that associated a risk factor with a disease, both lifestyle risks and biological risks. For initial studies, newspapers didn’t report on any null findings, meaning results without the expected outcomes. They rarely reported null findings even when they were confirmed in subsequent work.

Fewer than half of the “significant” findings reported on by newspapers were later backed by other studies and meta-analyses. Most concerning, while 234 articles reported on initial studies that were later shown to be questionable, only four articles followed up and covered the refutations. Often, the refutations are published in lower-profile journals, and so it’s possible that reporters are less likely to know about them. Journal editors may be as complicit as newspaper editors.

The good news is that the scientific community seems increasingly focused on solutions. Two years ago, the National Institutes of Health began funding efforts to create educational modules to train scientists to do more reproducible research. One of those grants allowed my YouTube show, Healthcare Triage, to create videos to explain how we could improve both experimental design and the analysis and reporting of research. Another grant helped the Society for Neuroscience develop webinars to promote awareness and knowledge to enhance scientific rigor.

The Center for Open Science, funded by both the government and foundations, has been pushing for increased openness, integrity and reproducibility of research. They, along with experts, and even journals, have pushed for the preregistration of studies so that the methods of research are more transparent and the analyses are free of bias or alteration. They conducted the replication study of psychological research, and are now doing similar work in cancer research.

But true success will require a change in the culture of science. As long as the academic environment has incentives for scientists to work in silos and hoard their data, transparency will be impossible. As long as the public demands a constant stream of significant results, researchers will consciously or subconsciously push their experiments to achieve those findings, valid or not. As long as the media hypes new findings instead of approaching them with the proper skepticism, placing them in context with what has come before, everyone will be nudged toward result that are not reproducible.

For years, financial conflicts of interest have been properly identified as biasing research in improper ways. Other conflicts of interest exist, though, and they are just as powerful — if not more so — in influencing the work of scientists across the country and around the globe. We are making progress in making science better, but we’ve still got a long way to go.

May 30, 2017

Market power matters

It’s the clash of titans.

In January the Massachusetts the Group Insurance Commission (GIC) — the state agency that provides health insurance to nearly a half-million public employees, retirees, and their families — voted to cap provider payments at 160% of Medicare rates. Ignoring Medicare (~1M enrollees) and Medicaid (~1.6M enrollees), the GIC is the largest insurance group in the state. According to reporting from The Boston Globe, the cap would be binding on a small number of concentrated providers, including Partners HealthCare, one of the largest hospital systems in the state.

David Anderson summed the development up perfectly.

The core of the fight is a big payer (the state employee plan) wants to use its market power to get a better rate from a set of powerfully concentrated providers who have used their market power to get very high rates historically.

Anderson also pointed to a relevant, recent study that illustrates how a specific payer’s and provider’s market power jointly affect prices. In Health Affairs, Eric Roberts, Michael Chernew, and J. Michael McWilliams studied the phenomenon directly, which has rarely been done. Most prior work aggregate market power or prices across providers or payers in markets.

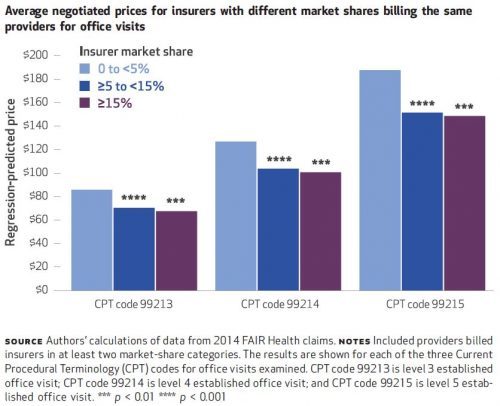

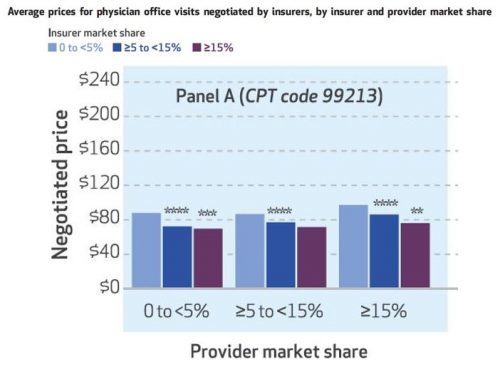

Their source of price data was FAIR Health, which includes claims data from about 60 insurers across all states and D.C. In a county-level analysis, the authors crunched 2014 data for just ten of those insurers that offered PPO and POS plans and that did not have solely capitated contracts. These ten insurers represent 15% of commercial market enrollment. They then looked at prices paid by these insurers to providers in independent office settings for evaluation and management CPT codes 99213, 99214, and 99215. These span moderate length visits to longer visits for more complex patients and collectively represent 21% of FAIR Health captured claims.

They computed insurer market share based on within-county enrollment. They computed a provider group’s market share as the county proportion of provider taxpayer identification numbers (TIN) associated with that group’s National Provider Identifier (NPI) — basically the size of group in terms of number of physicians.

Some of the findings are illustrated in the charts below and are largely consistent with expectations. For all three CPT codes, insurers with greater market shares tend to pay lower prices. That’s shown just below. The biggest price drop occurs when moving from

That tells the expected story of payer market power, but what about providers? The authors also look at that, and one of their sets of results is illustrated in the chart below, for CPT code 99213. Again, greater insurer market power is associated with lower prices — you can see that within each of the three sets of colored bars.

Each of those sets is for prices is for a different level of provider market share, 0 to 5%, ≥5 to 15%, and ≥15%. As one would expect, greater provider market share is associated with higher prices. Among providers with 0-5% market shares, the average CPT 99213 price is $88 for insurers with market shares of

The results are similar for the other two CPT codes: higher prices are independently associated with greater provider market share and lower insurer market share.

From the research literature, we’ve long known that provider consolidation leads to higher prices. One of the arguments for insurer consolidation is to push prices downward. However, that doesn’t imply that the right policy approach to high health care prices is greater insurer market power, as there’s no guarantee that dominant insures will pass lower prices onto consumers. Minimum medical loss ratio regulations that would limit insurer relative profit margins don’t necessarily help because they could encourage a dominant insurer to keep price levels higher to extract higher absolute profits.

However, other approaches that push prices downward can help consumers as well. One example is reference pricing. Other approaches include price transparency, higher consumer cost sharing, and narrowing of networks. (Not all of these have been shown to consistently achieve their intended results.) These are not mutually exclusive approaches. The GIC, in addition to flexing its market power to push prices downward, has also offered narrow network plans that have saved enrollees substantially.

For lowering health care prices, there are a lot of tools in the toolbox. But history suggests we haven’t settled on ones that both work and that patients and other stakeholders are willing to tolerate for long. Continued experimentation and analysis is essential.

May 24, 2017

Allergies are even worse than you think

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2017, The New York Times Company)

This is the time of year my kids and I have seasonal allergic rhinitis, better known as hay fever. I’d always thought it was merely a nuisance, but it turns out it also degrades cognitive performance, at least a little.

Hay fever affects at least 10 percent of the population, and a higher percentage of children. The most obvious signs of allergic response include sneezing, itching and a runny nose. These can disrupt sleep, leading to fatigue, and the allergy can cause neurocognitive deficits we may not notice in ourselves or in our children. Medications used to treat the allergy can also induce sleepiness in some people.

In the United States, school-age children collectively lose about two million school days because of pollen allergies. Even when they attend school, allergy-suffering students may perform a bit worse than their nonallergic counterparts.

Using data from Norway, a recent study shows that when pollen levels rise, students’ test scores fall. The study used data from nearly 70,000 high school exit exams, which Norwegian students must pass to graduate and are used for higher education placement. Students take exams at different locations, and each student takes several at different times of year, providing multiple data points per student.

The study’s author, Simon Bensnes, a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Economics at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, combined these with pollen count data linked to the location and time at which each student took each exam, as well as other demographic and air-quality data used to control for potentially confounding factors.

Pollen counts are measured in grains of pollen per cubic meter of air and can be as high as the 100s at the height of pollen season in Norway. For students allergic to pollen, Mr. Bensnes found that a pollen count increase of 37 — large enough to cause symptoms in highly allergic people — is associated with a drop of about one-tenth of a point in exam scores. The scores range from one (worst performance) to six (best performance).

Does such a seemingly small effect matter in the long run? Other results suggest they do. The study also finds that higher pollen counts correlate with a slightly lower likelihood of enrolling in a university and a lower probability of going into a STEM field. However, though the statistical methods to analyze test scores are rigorous enough to reasonably infer they’re causal, the ones for these longer-term results are less so.

Still, Mr. Bensnes said, “it would be surprising if there were no effects in the longer run.” This is particularly likely in countries where exams are weighed more heavily than in Norway toward entrance to institutions of higher education. There, exams count only for about 15 percent of entrance determinations.

Norway is not the only setting where a pollen-exam relationship has been found. In Britain, students take an exit exam at the end of secondary education in the spring or summer, when pollen counts are high. They also take a practice test the prior winter. Researchers found that compared with those with no allergy symptoms, British students who report allergies or take allergy medications during their secondary education exit exams are 40 percent to 70 percent more likely to score a full grade lower than they did on their practice test.

A study in the United States found that a doubling of the pollen count is associated with about 1 or 2 percent drop in the proportion of third graders passing English and math achievement tests.

Clinical studies have examined the cognitive effects of hay fever more directly. For example, a study found that people with hay fever experienced slower speeds of mental processing during ragweed season than at other times of year. Another study exposed allergic people to pollen in a controlled setting. It found that they exhibited slower mental function, decreased memory, and poorer reasoning and computation abilities compared with nonallergic test subjects.

More generally, what we breathe affects how well we perform at school or work. Several studies found a link between air pollution and school absences, as well as labor supply and worker productivity. Worse air quality can cause or worsen respiratory problems, like asthma, reducing some children’s ability to attend school and adults’ entry into the work force. It can also harm job performance.

One study found that higher concentrations of certain air pollutants hurt test scores of Israeli students and the chances of passing a high school exam necessary for higher education.

Individually, we may not be able to do much about air pollution, but we can try to reduce the impact of pollen on school and work performance. Finding allergy medication that doesn’t induce drowsiness is an obvious approach. When it comes to high-stakes exams, it may be worth choosing test dates outside the allergy season, if possible. Hay fever is rarely debilitating, but its small effects can put us off our best game.

May 22, 2017

Improving reproducibility in research – There’s a Healthcare Triage series for that!

Very, very rarely in science do we achieve a result that we are absolutely, positively sure is correct. We almost always use statistics to give us some estimate of how likely we believe our results to be true, but that answer rarely equals 100%.

But we’d like to think that most of what we find, write up, and publish is correct. One way to define “correct” is as something that someone else can reproduce.

What do I mean by that? I mean that if someone else does the same experiment as me, in another time, in another place, they get the same result. I mean that – over time – people are able to get the same results I do when they perform similar experiments.

By this metric, many areas of science are falling far short of what we’d like.

Many are working on solutions to these issues. Journals are beginning to band together and discuss how to do better reviews. Many trials now need to be registered so that decisions have to be made about how to design, conduct, analyze, and report findings before the research takes place, while researchers are still behind the veil of ignorance.

The NIH has also gotten involved by calling for the creation of training modules to enhance data reproducibility. They are focusing their efforts on four domains:

Experimental design

Laboratory practices

Analysis and reporting

And the Culture of science

A few years ago, they put out a Request for Applications in this area, and we at Healthcare Triage were funded! We have tackled two of these domains, Experimental Design and Analysis and Reporting. We like to think we’ve got something to say about what makes a good study, well, good. We explored all the key concepts you need to consider in order to ensure that your research is as bias-free as possible.

And, we think we’re pretty good at analysis and reporting as well. Therefore, we talked about what makes a good paper, how to present and discuss your results, and how to avoid the mistakes many make in overselling their findings.

Both of these modules consist of many episodes, or chapters. They’re all short and sweet, they’re all freely available, and they’re open to anyone. If you’re interested in learning about CME for watching these videos, go here for Experimental Design and here for Analysis and Reporting.

We also would appreciate feedback. There’s a short survey you can fill out after you watch the series.

It’s hoped that these modules will help scientists at all levels improve the quality of their experiments and how they report them, and that by doing so, we might improve the problems we’re currently seeing in many areas of research in terms of reproducibility. Please share these videos widely!!!

This training module is part of a series funded by the National Institutes of Health under grant R25GM116146

P.S. Let me add that none of this would ever be possible without Stan Muller and Mark Olsen, my co-pilots at Healthcare Triage, John Green, who executive produces, and Austin Frakt and Jen Buddenbaum, who consulted on all of the scripts!

Healthcare Triage News: The Advantages of Medicare Advantage

Many studies have demonstrated what economics theory tells us must be true: When consumers have to pay more for their prescriptions, they take fewer drugs. That can be a big problem. This is Healthcare Triage News.

This episode was adapted from a column Austin wrote for the Upshot. Links to sources can be found there.

Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers