Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 133

June 15, 2017

Cystic Fibrosis, Life Expectancy, and the Greatest Health Care System in the World

Cystic fibrosis is an inherited disorder that affects the lungs, pancreas, intestines and other organs. A genetic mutation leads to secretory glands that don’t work well; lungs can get clogged with thick mucus; the pancreas can become plugged up; and the gut can fail to absorb enough nutrients.

It has no cure. Over the last few decades, though, we have developed medications, diets and treatments for depredations of the disease. Care has improved so much that people with cystic fibrosis are living on average into their 40s in the United States. In Canada, however, they are living into their 50s. That’s the topic of this week’s Healthcare Triage.

This episode was adapted from a column I wrote for the Upshot. Links to reading and further references can be found there.

There’s No Magical Savings in Showing Prices to Doctors

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2017, The New York Times Company).

Physicians are often unaware of the cost of a test, drug or scan that they order for their patients. If they were better informed, would they make different choices?

Evidence shows that while this idea might make sense in theory, it doesn’t seem to bear out in practice.

A recent study published in JAMA Internal Medicine involved almost 100,000 patients, more than 140,000 hospital admissions and a random distribution of laboratory tests. During the electronic ordering process, half the tests were presented to doctors alongside fees. While the cost to the patient might vary, these Medicare-allowable fees were what was reimbursed to the hospital for the test or tests being considered. The other half of the tests were presented without such data.

The researchers suspected that in the group seeing the prices, there would be a decrease in the number of tests ordered each day per patient, and that spending on these tests would go down. This didn’t happen. Over the course of a year, there were no meaningful or consistent changes in ordering by the doctors; revealing the prices didn’t change what they did much at all.

This isn’t the first time a study like this found that showing prices to doctors doesn’t make a difference. Earlier this year, a study published in Pediatricsreported on a similar randomized controlled trial on physicians caring for children. In this case, doctors were randomized to one of three groups. The first group saw the median price of a test when they ordered it. The second saw both the price (often lower) when obtained within the current health care system and outside it. The third group saw no price at all.

Pediatric-focused clinicians showed no effect from price displays. Adult-focused clinicians actually ordered more tests when they saw the prices.

A similarly designed study of more than 1,200 clinicians in an accountable care organization published earlier this year also found no effects from telling physicians prices.

Some older studies have found that physicians might alter their behavior on individual tests, but in only five of the 27 they examined. Another found a small, but statistically significant, difference. Unfortunately, this study suffered from asymmetric randomization. Even before the intervention began, the tests chosen for the price-showing group were ordered more than three times as much as those chosen for the control group. More expensive tests appeared in the control group for some reason as well.

Of course, any one study has the potential to be an outlier or subject to limitations that might warrant skepticism. These can be minimized by looking at the body of evidence in systematic reviews.

One was published in 2015, and argued that in the majority of studies, giving physicians price information changes their ordering and prescribing behavior to lower the cost of care. A closer look, though, reveals that most of the studies in this analysis were more than a decade old. Many took place in other countries. And all were published before these latest, and largest, studies I discussed above. Another systematic review that looked at interventions focusing only on drug ordering found similar results, with similar caveats.

I should be clear: We have good reason to want to believe that interventions focusing on giving physicians information about the prices of the things they order should make a difference. In 2007, a systematic review demonstrated that doctors were ignorant of the costs of prescription drugs. They underestimated the prices of expensive drugs, overestimated the prices of inexpensive ones, and did not understand the extent of the difference in price between those considered cheap and those considered pricey. Another, published in 2015, explored 79 studies, 14 of which were randomized controlled trials, that suggested that physicians could be educated to deliver “high-value, cost-conscious care.”

But that education probably needs to be holistic. Flashing one point of data at a doctor does not get the job done; knowledge transmission needs to be accompanied by what this review called “reflective practice and a supportive environment.” Simply focusing on cost information may not be enough. The reasons that physicians order tests are more than financial, and efforts to influence their behavior most likely need to be more than informational.

Additionally, it may be that issues of price transparency need to involve more than one component of the health care system. While focusing solely on physicians, or on patients, might not work well, trying to work on both simultaneously might. It’s also possible that intervening solely on one procedure, test or drug at a time may not be as powerful as trying to influence spending on care over all.

Finally, trying to make physicians focus strictly on cost may be off base as well. Some care, even more expensive care, is worth it. What we really should attend to is value — the quality and impact relative to the cost. It is certainly harder to determine value than price, but that metric might make more of a difference to physicians, and to their patients.

Something for you to read

I’m human; I can admit when I’ve screwed up. I took on more than I can handle these last few months, and that’s seriously cut into my blogging. The good news is that things are lightening up at the end of this month, and I plan a triumphant return in July.

In the meantime, go read this “Medicine and Society” essay in the NEJM by Louise Aronson Debra Malina. Best graf:

Those structural inequalities might lead a Martian who landed in the United States today and saw our health care system to conclude that we prefer treatment to prevention, that our bones and skin matter more to us than our children or sanity, that patient benefit is not a prerequisite for approved use of treatments or procedures, that drugs always work better than exercise, that doctors treat computers not people, that death is avoidable with the right care, that hospitals are the best place to be sick, and that we value avoiding wrinkles or warts more than we do hearing, chewing, or walking.

The whole thing is worth your time.

June 13, 2017

Maybe I was wrong about ACOs

It was at the 2009 AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting in Chicago that I learned about accountable care organizations (ACOs). The day after leaving the meeting, I was already concerned:

[I]f the U.S. health care system moves toward an ACO model we will see greater provider consolidation, all other things being equal. Provider groups’ greater market power to negotiate higher payments will be a countervailing force against the promise of the ACO model to provide higher quality care at lower cost.

I have not been alone in harboring this reservation about ACOs. For years, I and others have viewed ACOs as one of several legal and regulatory motivations for provider consolidation. The logic goes like this: the ACO model encourages the provision of more coordinated care for a population of patients. In addition, it rewards provider organizations for higher quality and lower costs. Historically, all of these are have been justifications for provider consolidation, including the horizontal integration of hospitals, the horizontal integration of physician practices, and the vertical integration of hospitals and physician groups.

But, a recent paper by Hannah Neprash, Michael Chernew and J. Michael McWilliams suggests this logic may be flawed. By comparing changes in provider consolidation from 2008–2010 to 2011–2013 between markets with higher versus lower Medicare ACO penetration (as measured in 2014), they found no evidence of a change in the trend toward consolidation associated with ACO adoption.

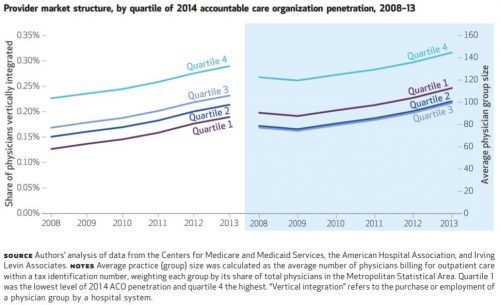

The chart, just below, summarizes the main findings. Though vertical integration of physicians with hospitals (left panel) and physician group size (right panel) both increased over the study period, the rate of growth for both was identical across quartiles of 2014 ACO penetration. Here, ACO penetration is measured at the metropolitan statistical level as the proportion of Medicare beneficiaries attributed to an ACO.

Many other measures assessed by the authors — changes in physician market concentration, hospital market

concentration, and commercial health care prices — are consistent with the hypothesis that the Medicare ACO model did not encourage consolidation. However, mean physician group size grew more rapidly for physicians participating in an ACO, relative to physicians who did not.

From this evidence, it seems I was (and others were) wrong to blame ACOs for consolidation of health care providers … maybe.

But, the authors also found an increase in hospital mergers after the Affordable Care Act became law alongside an inverse relationship between hospital market concentration and ACO penetration. This leads to a different hypothesis about how ACOs might influence market concentration after all:

These findings suggest that new payment models may have triggered some consolidation as a defensive reaction to the threat these models could pose, rather than as a way to achieve efficiencies in response to the new incentives. Hospitals and specialists in particular might consolidate both horizontally and vertically to achieve sufficient market share to resist payer pressure to enter risk contracts or weaken ACOs’ ability to exploit competition in hospital and specialty markets, to compel reductions in prices and service volume.

It takes a close read to understand what the authors are saying here. It’s not necessarily about Medicare ACOs, but about ACOs more generally (including commercial market ACOs). They’re saying that providers might consolidate to resist this broader ACO movement and/or its implications for pressure on prices and volume. However, it’s a reasonable hypothesis that commercial market ACO presence is correlated with Medicare ACO presence across markets. Therefore, observations of relationships between consolidation and Medicare ACO penetration may also be valid for informing inferences about broader relationships involving commercial market ACOs as well.

The upshot is that maybe the ACO model is influencing consolidation, just not in the way I and others had thought. Rather than consolidating to support the ACO model, providers may be doing so as a defense against it. It’s too soon to know for sure. More work needs to be done to gather evidence to support or refute this alternative hypothesis.

June 12, 2017

A question for single payer advocates: Where do the votes come from?

Alexander Burns and Jennifer Medina report in The New York Times that

At rallies and in town hall meetings, and in a collection of blue-state legislatures, liberal Democrats have pressed lawmakers, with growing impatience, to support the creation of a single-payer system, in which the state or federal government would supplant private health insurance with a program of public coverage.

I support universal health insurance: I voted with my feet to work in Canada. When the office of an outspoken New England legislator asked me for comments on the text of a single-payer bill, I was glad to give them.

My question is: How do advocates plan to build a coalition that could pass single-payer?

I’m not talking about the current weakness of the Democratic Party. Let’s assume a future in which the Democrats have recaptured the presidency and the Congress. Let’s assume that Republican health care policies are supported by only about 1 in 5 Americans, as is the case today.

The problem is that even in these circumstances, I fear that many Americans will judge the risk of a financial loss in a transition to single payer to be greater than the benefit they are likely to receive from single payer.

Consider that 49% of Americans have health coverage through their employer (7% have non-group coverage, 36% have public insurance, and 9% are uninsured). These employees aren’t getting health insurance for free. They pay for their insurance benefit through foregone wages. But it often looks to them like they are getting insurance for small premiums, if not for free. If they have to pay for their insurance through increased taxes, many will likely perceive that they have suffered a net loss.

Moreover, some people would suffer an actual loss in a transition from employer-supplied health insurance to single-payer. In theory, we might expect an employee’s compensation would rise enough to cover the tax costs of single-payer, but that won’t happen for everyone. Some people will be net losers.

In part, this is because a universal care system will, by design, help equalise access to health care. Suppose we tried to do this through a scheme that held total health care spending constant. Then making access more equal would require redistributing some health care resources from the haves to the have-nots. That might be just, but the haves would hate it. And they vote.

Alternatively, we could bring the care of the underserved up to the standard of the well-served. This will require increased health care spending and an even larger increase in taxes. Most of those taxes would come from the affluent. The affluent already have good insurance, so they gain little from single payer. Again, the haves are net losers.

As I see it, there won’t be a sustainable US single-payer system unless we can make American health care more efficient. Efficient enough so that you can level the have-nots up to health care standard of the haves without increasing spending. There are theories — or at least stories — about how to do this. Single payer would reduce administrative costs. A single insurer would have great power to knock down the prices charged by manufacturers, hospitals, doctors, and nurses. Either course will involve political warfare against powerful industries.

There is a counterargument against my pessimism. Other developed countries have single-payer (or other forms of) universal health care. If, Canada did it, why can’t the US make the same transition?

However, the US may have missed the window when establishing a single-payer system would have been comparatively easy. The Canadian transition began in Saskatchewan in 1947. Saskatchewan farmers were largely uninsured and had nothing to lose in the transition to public insurance.

So my question for single-payer advocates is, where do the votes come from?

June 9, 2017

Healthcare Triage News: Prostate Screenings Are Cool Again!

The guidelines for screening for prostate cancer have changed. Again! And that’s ok! The USPSTF is hard at work. This is Healthcare Triage News.

Resources:

The US Preventive Services Task Force 2017 Draft Recommendation Statement on Screening for Prostate Cancer

Prostate Cancer Screening — A Perspective on the Current State of the Evidence

Screening and prostate cancer mortality: results of the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) at 13 years of follow-up

Trends in Management for Patients With Localized Prostate Cancer, 1990-2013

June 8, 2017

JAMA Forum: Why Is US Maternal Mortality Rising?

I’ve written about maternal mortality on this blog a number of times (for example here, and here, and here). But the data are getting even more concerning, and it’s not something we can ignore. I delve more deeply into the subject in my latest post over at the JAMA Forum. Go read!

New study doesn’t support AAP guidelines on infant room-sharing

Last year, Claire Caine Miller and I teamed up to write about the then-new AAP guidelines on infant sleep. Those guidelines recommended that infants sleep in the same room as their parents until they were one year of age. We took issue with that.

We noted that the “evidence” for this recommendation consisted of one out-of-print book from the 1990’s, and three old case-control studies, none of which took place in the US. We noted that cultural practices in other countries differ from those here. We noted that the incidence of SIDS has been greatly reduced from when those studies were conducted, so there may be diminishing returns to interventions. We also noted that it would likely result in poorer sleep for all involved, which isn’t good for anyone.

A new study was just published in Pediatrics. As part of an obesity prevention trial RCT involving responsive parenting, researchers gathered data on sleep patterns of new mothers. They looked at sleep duration and overnight behaviors of all mothers, comparing early independent sleepers (an infant in his or her own room by 4 months of age), late independent sleepers (own room by 9 months of age), and room-sharers (sharing still at 9 months of age).

What they found was that early independent sleepers had better sleep consolidation (sleeping longer at a stretch of time) by four months of age. At nine months, early independent sleepers slept 40 minutes longer over the course of a night than room sharers; they also slept 26 minutes longer than late independent sleepers. They also slept much more at a time without waking up. These differences were still seen at 30 months of age, even when the changes occurred earlier.

Further, those who room shared had a much greater chance (OR 4.24) of transitioning to bed-sharing in the middle of the night when the baby woke up. That’s considered very unsafe. The AAP guidelines strongly recommend against that.

But, come on, when you have a baby in the room, and it keeps waking up… that’s eventually what parents do. I can tell you this from experience, and from empirical studies now.

So, to recap, when parents room-share their babies sleep less overall, they wake up more, everyone gets less sleep, and parents often respond by bringing them into the bed with them – which is very unsafe. Let me quote for you from the conclusions of the paper (emphasis mine):

While substantial progress has been made over the past several decades to improve the safety of infant sleep, the AAP recommendation that parents room-share with their infants until the age of 1 year is not supported by data, is inconsistent with the epidemiology of SIDS, is incongruent with our understanding of socioemotional development in the second half of the first year, and has the potential for unintended consequences for infants and families. Our findings showing poorer sleep-related outcomes and more unsafe sleep practices among dyads who room-share beyond early infancy suggest that the AAP should reconsider and revise the recommendation pending evidence to support room-sharing through the age of 1 year.

Those of you who read our column in the NYT last November* already knew that.

*So far this is my one appearance in the Sunday NYT. I’m rather proud of that. Plus, I got to write with Claire Cain Miller!

Horrifying numbers on drug overdoses

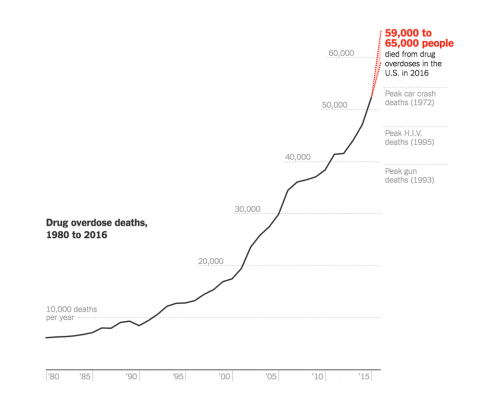

From Josh Katz in The New York Times Upshot:

How bad is this?

The Times estimates that 62,500 Americans died of drug overdoses in 2016.

That’s 50% more than the deaths from AIDS in the peak year of the epidemic (41,699 in 1995).

It’s the worst single-year mortality event in 60 years, when 70,000 Americans died in the 1957 Asian flu pandemic.

It’s twice the number of annual US traffic deaths.

It’s four times the number of Americans killed annually by firearms.

The increase in deaths in 2016 — about 10,000 more than 2015 — is more than three times the total number of Americans who have been killed by terrorists since the morning of 2001/09/11.

Katz: “Drug overdose is now the leading cause of death among Americans under 50.”

The estimated one-year increase from 2015 to 2016 is 19%. If that rate of growth were to continue — and surely it CAN’T — the annual deaths would double in about 3.7 years. The doubling time for the number of deaths is falling, meaning that epidemic is accelerating.

The drug overdose epidemic is a public health catastrophe in the same class as AIDS.

June 7, 2017

Teaching Hospitals Cost More, but Could Save Your Life

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2017, The New York Times Company).

Perhaps not evident to many patients, there are two kinds of hospitals — teaching and nonteaching — and a raging debate about which is better. Teaching hospitals, affiliated with medical schools, are the training grounds for the next generation of physicians. They cost more. The debate is over whether their increased cost is accompanied by better patient outcomes.

Teaching hospitals cost taxpayers more in part because Medicare pays them more, to compensate them for their educational mission. They also tend to command higher prices in the commercial market because the medical-school affiliation enhances their brand. Their higher prices could even cost patients more, if they are paying out of pocket.

To save money, insurers have started establishing hospital networks, and policy makers are considering ways to steer patients away from teaching hospitals. Those efforts may well save patients and taxpayers money. But how will that affect the quality of care?

One answer is provided in a new study of over 21 million hospital visits paid for by Medicare in 2012 and 2013. Teaching hospitals save lives. For every 83 elderly patients seen by a major teaching hospital, one more is alive 30 days after discharge than if those patients had been admitted to a nonteaching hospital. This is a large mortality effect.

“It’s about half the size of a breakthrough medical therapy like stenting for heart-attack patients,” said Amitabh Chandra, an economist with the Harvard Kennedy School and a longtime skeptic of the value of teaching hospitals, who wasn’t involved in this study.

“Minor” teaching hospitals — which also have educational missions but are not members of the Council of Teaching Hospitals and Health Systems — also outperformed nonteaching hospitals, but by a smaller margin.

The study, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, adjusted for other factors that could have skewed the results, like demographics, patients’ diagnoses, hospital size and profit status. Because mortality rates differ geographically, it compared teaching with nonteaching hospitals within the same state. Even after such adjustments, it found mortality rates are lower at teaching hospitals for 11 of 15 common medical conditions and five of six major surgical conditions. The more medical students per bed a hospital had, the lower its mortality rate.

Given the importance of this issue, you’d think we would already know the mortality differences between teaching and nonteaching hospitals. But the seminal studies on the subject are based on data at least two decades old. Other, more recent studies focus on only a few types of patients or offer conflicting results.

“We thought the comparative performance of teaching and nonteaching hospitals was worth a fresh look because medicine has changed considerably since those older studies,” said Laura Burke, the lead author on the study and an emergency physician with the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “And the more recent studies don’t settle the question.” (I am a co-author on the study, along with Dr. Burke and other Harvard colleagues Dhruv Khullar, E. John Orav and Ashish Jha. Dr. Khullar is also an Upshot contributor.) The study was funded by the American Association of Medical Colleges, which had no editorial control over analysis or publication.

Though the study revealed mortality differences by teaching status, it could not illuminate the cause of those differences. Perhaps teaching hospitals attract higher-quality practitioners, more closely follow best practices, or use medical technology more effectively.

Other studies suggest teaching hospitals do not offer higher quality more broadly. For example, an analysis led by Jose Figueroa, a physician with the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, found that teaching hospitals were more likely to be penalized by Medicare for low quality compared with nonteaching hospitals. Another study found teaching hospitals were more likely to be penalized for higher hospital readmission rates.

An examination of Massachusetts hospitals found comparable quality performance at teaching and nonteaching hospitals. The state has a goal — codified in a 2012 state law — of bringing health care spending growth in line with overall economic growth. The Massachusetts Health Policy Commission has highlighted the high costs of teaching hospitals as part of this effort.

The new study did not assess the cost of the benefits in mortality that teaching hospitals deliver.

“The typical teaching hospital is at least 30 percent more expensive,” Mr. Chandra said. “Is 1 percent fewer deaths worth that price?” It’s a question few like to ask, but spending more on hospital care means less for other things we value — and that are known to improve health and welfare, too — like education and nutrition programs.

About 26 percent of hospitals are teaching hospitals, accounting for just over half of all admissions. Unsure which hospitals in your area are teaching hospitals? It’s something most of them make a point of mentioning, so you can often find a hospital’s teaching status on its website. If not, an inquiry to the hospital should settle the matter. If you use one, the cost of your care will be higher, but it might save your life.

Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers