Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 130

July 7, 2017

Healthcare Triage News: The Senate’s BCRA Bill – High Premiums, Huge Deductibles, AND Massive Medicaid Cuts

We’re going to make a serious attempt to make Healthcare Triage News more “newsy”. Here’s our first week. Catch up to date on the BCRA and the CBO Report!

Medicaid is good for children and makes them better adults

The Senate’s Better Care Reconciliation Act (BCRA) significantly cuts Medicaid, the program that insured 39% of US children in 2015 and 50% or more in New Mexico, West Virginia, and Mississippi. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the BCRA will increase the number of uninsured Americans by 22 million, among them many of those currently covered by Medicaid. However, many supporters of these bills argue either that Medicaid delivers no health benefits to the insured or actually harms them. If this is what they believe, then surely reducing Medicaid enrollment is a virtue of the BCRA, not a flaw.

Whether Medicaid is harmful has been debated for years. In this post, I call your attention to emerging evidence that Medicaid benefits children.

Liberals have trouble understanding how Medicaid could be harmful. It’s true that some doctors are less likely to accept a Medicaid patient than a privately insured one. However, a doctor who turns down a Medicaid patient would be even less likely to care for an uninsured one. So how could the well-being of someone on Medicaid be improved if they became uninsured?

These liberals have missed the point of the conservative argument. That view, best articulated by Charles Murray, is that the social safety net harms you by exposing you to incentives that keep you dependent. In a welfare-dependent family, it’s harder for a child to develop into an independent, functional adult. Getting social assistance, therefore, traps you and your family in poverty. The strong prediction by conservatives is that poor kids who grow up as dependents of the welfare state will be less healthy and less functional than other kids.

Arguments that Medicaid is ineffective usually cite the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment (OHIE). This randomized experiment found that getting Medicaid coverage did not improve several important physiological measures of health. Benjamin Sommers, Atul Gawande, and Katherine Baicker (who was the Principal Investigator of the OHIE) rebut this argument in the NEJM. Likewise, Aaron and Austin argue in The New York Times that Medicaid critics have misinterpreted the research. According to these analysts, the OHIE had little chance to find substantial physiological benefits because it studied a small group of people for a relatively brief period of time. Other studies involving large populations and designs that allow causal inferences have shown that getting Medicaid saves lives.

It follows that the ideal study of Medicaid would look at large populations of people over long periods of time with a design that was a randomized experiment or approximated one. It turns out that this is to some degree possible if you look at the child and adult health outcomes of kids who grew up in states where poor families had varying degrees of access to Medicaid.

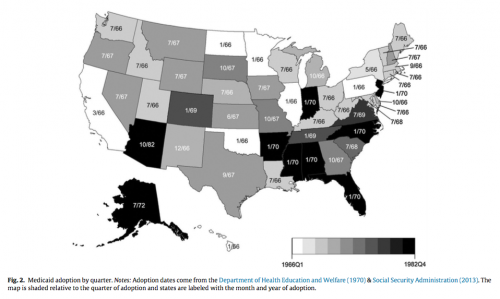

Congress created Medicaid in 1965, but because it is administered and paid for by both states and the federal government, states started their programs at different times and varied in who they covered. This map from the Social Security Administration shows the year and quarter when states began Medicaid.

The month/year in which states adopted Medicaid. From Boudreaux et al.

This means that poor kids born in 1966 in Oklahoma, which started Medicaid in that year, were likely to have had much more cumulative insurance coverage by the time they reached adulthood than kids born in 1966 in Arizona, which started Medicaid in 1982. So if Medicaid is bad for you, then everything else being equal the states that had larger proportions of kids covered for longer periods of time should have populations of adults that look worse, on average, than other states.

Several groups of analysts have looked at state health outcomes following this strategy. Importantly, these researchers have looked at many aspects of adult well-being, not just health. For example, Cohodes, Grossman, Kleiner and Lovenheim examined

the effects of the public insurance expansions among children in the 1980s and 1990s on their future educational attainment. Our findings indicate that expanding health insurance coverage for low-income children increases the rate of high school completion and college completion… We present suggestive evidence that better health is one of the mechanisms driving our results by showing that Medicaid eligibility when young translates into better teen health. Overall, our results indicate that the long-run benefits of public health insurance are substantial. (Ungated version here.)

Boudreaux, Golberstein, and McAlpine analyzed data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics. They found that Medicaid coverage in early childhood (age 0–5) was associated with statistically significant and meaningful improvements in adult health (age 25–54). Interestingly, they found that Medicaid was associated with lower blood pressure and a lower overall chronic disease score, which contrasts with the lack of physiological effects in the OHIE. Boudreaux and his colleagues found these benefits only among the low-income people most likely to have been covered by Medicaid.

Miller and Wherry studied

how a rapid expansion of prenatal and child health insurance through the Medicaid program affected adult outcomes of individuals born between 1979 and 1993 who gained access to coverage in utero and as children… We find that cohorts whose mothers gained eligibility for prenatal coverage under Medicaid have lower rates of obesity as adults and fewer hospitalizations related to endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases, and immunity disorders as adults. We also find that the prenatal expansions increased high school graduation rates among affected cohorts.

Meyer and Wherry looked at

a policy discontinuity [in] several early Medicaid expansions that extended eligibility only to children born after September 30, 1983… We find a substantial effect of public eligibility during childhood on the later life mortality of black children at ages 15-18. The estimates indicate a 13-20 percent decrease in the internal mortality rate of black teens born after September 30, 1983.

Andrew Goodman-Bacon found that

Before Medicaid, higher- and lower-eligibility states had similar infant and child mortality trends. After Medicaid, public insurance utilization increased and mortality fell more rapidly among children and infants in high-Medicaid-eligibility states. Mortality among nonwhite children on Medicaid fell by 20 percent, leading to a reduction in aggregate nonwhite child mortality rates of 11 percent.

In another analysis, Goodman-Bason looked at the effect of Medicaid coverage when you are 0 to 10 years old on adult mortality rates, whether the children found employment when they became adults, and what they received in transfer payments.

For mortality, he reported that

about 345,000 lives were saved between 1980 and 1999—54,000 among whites and 291,000 among nonwhites.

For rates of disability,

each full year of early-life cumulative [Medicaid] eligibility reduces white ambulatory difficulty rates by 3.8 percentage points (s.e. = 1.2) and nonwhite rates by 2.9 percentage points (s.e. -1.8).

For employment,

each year of childhood Medicaid eligibility reduces the probability of being out of the labor force by 6.6 percentage points (s.e. = 1.5)

These reductions in disability and unemployment among kids covered by Medicaid in early childhood reduced the social assistance transfer payments the Medicaid kids received as adults. As a result,

The government earns a discounted annual return of between 2 and 7 percent on the original cost of childhood coverage for these cohorts, most of which comes from lower cash transfer payments.

Are these findings credible? These are complicated analyses with many moving parts. A lot hangs on the idea that you can make an “everything else being equal” comparison between states based on how they administered Medicaid. Looking at the map above, there are regional correlations in when states started Medicaid, and there are likely correlations with state poverty and other factors. Yet even within regions, there is variation in when Medicaid started and how it was run. The papers I’ve summarized look for this kind of variation in Medicaid coverage policies between comparable states. This variation allows them to infer that Medicaid coverage during early childhood caused these better child and adult outcomes. It’s a large claim and it’s certain to be disputed.

But if you accept this analytical strategy, what do these findings show?

First, the prediction that Medicaid harms children is flat wrong. There’s no evidence that Medicaid kids are worse off. To the contrary, on several important outcomes kids were better off if they grew up in states that started Medicaid coverage earlier and covered more kids.

Second, it appears that the most important times for coverage are when you are in-utero, an infant, or a young child. This reinforces James Heckman’s argument that early childhood is a critical period where we get the highest return for investments in improving the social determinants of health and human development.

Third, the effects of early exposure to Medicaid are found not just in health, but also in educational attainment, employment, and reduced welfare dependency. In other words, Medicaid works on precisely the issues that conservatives care the most about. Provision of Medicaid to families with poor children appears to give those kids a better chance of growing up to be high functioning adults. As such, it promotes fair equality of opportunity. Conversely, these findings count against predictions that Medicaid traps children in lives of poverty.

What the findings do not show is that Medicaid, or public health insurance of any kind, is the optimal way to invest in families or child development. It would help if we knew how Medicaid benefits children. Is it increased access to health care, is it because health insurance reduces the out-of-pocket costs to families, or is it because having health insurance reduces the psychological stress of being a family? These studies don’t tell us. So it’s possible that some other policy would help kids more. For example, we don’t know whether paying for a poor family’s Medicaid is more cost-effective than giving that family the actuarially-equivalent cash.

This and similar proposals deserve serious consideration. But it is critical to note that the comparison between providing Medicaid and giving cash is irrelevant to the debate about the BCRA and the House of Representatives’ American Health Care Act of 2017. Instead of taking resources from Medicaid to fund cash transfers to the poor, these bills take cash out of Medicaid to fund tax cuts for the wealthy.

Finally, these findings cast light on the American (and far stronger Canadian) commitments to a decentralized federal system for the administration of public health insurance. Justice Brandeis argued that federalism — meaning here that states that have considerable autonomy in how they implemented Medicaid — is valuable to the country as a whole. It’s valuable because a

state may, if its citizens choose, serve as a laboratory; and try novel social and economic experiments without risk to the rest of the country.

Many argue, following Brandeis, that federalism is a way to learn what works in social policy.

To learn about policy, however, we have to ask how can we actually get reliable information from the laboratories of the states. One answer is that we do it through differences-in-differences analyses of variation in the implementation of state programs, such as those that we have reviewed above. If you believe that the independence of states gives us a laboratory for democracy, you should take seriously the results on Medicaid that have come back from the lab.

July 6, 2017

Where are the Democrats’ ACA fixes?

That’s what the Republican National Committee wants to know, putting the question in a new ad. This is one of the oldest rhetorical tricks in the book, and to be fair has been used by both sides on many issues. It’s the “Have you stopped beating your wife?” tactic. It works when one only hears the question but never the answer.

These days, many hearing the question won’t even look for the answer. They’ll just assume there are no Democratic or progressive ideas to fix the ACA.

But there are. I asked for them on Twitter this morning and here’s a taste of what I got, just as of noon today:

Jost/Pollack: https://t.co/a5UuFDg3E2

Urban: https://t.co/HUmFKyxQDc

Some weirdo: https://t.co/Hcp97VKkZh

— Adrianna McIntyre (@onceuponA) July 6, 2017

Details on Clinton's plan here https://t.co/BuQjy1887V

— Jonathan Cohn (@CitizenCohn) July 6, 2017

Here’s 20 of them: https://t.co/MVdlyVbDRj

— ☪️ Charles Gaba ✡️ (@charles_gaba) July 6, 2017

Yeah, you have to click through and read a bit. But if you want the answer, it’s there. There are lots of ideas to fix the ACA that are not what the GOP is proposing. Nevertheless, one good tactic for diverting attention from a troubled plan pushed through in a closed process is to ask where your opponent’s is. I don’t fault the RNC for trying it out.

Obesity is bad. It really is.

I wrote a lot of titles to this post, and all of them inadvertently had puns in them (Big problem, Massive problem, Huge problem, etc). But they’re all true. A huge review was just published in the NEJM: “Health Effects of Overweight and Obesity in 195 Countries over 25 Years”

Background: Although the rising pandemic of obesity has received major attention in many countries, the effects of this attention on trends and the disease burden of obesity remain uncertain.

Methods: We analyzed data from 68.5 million persons to assess the trends in the prevalence of overweight and obesity among children and adults between 1980 and 2015. Using the Global Burden of Disease study data and methods, we also quantified the burden of disease related to high body-mass index (BMI), according to age, sex, cause, and BMI in 195 countries between 1990 and 2015.

This group basically searched Medline for studies that had a nationally or otherwise significant representative estimate of BMI, overweight, or obesity in kids or adults. They identified thousands of unique data sources for more than 170 countries. They used “spatiotemporal Gaussian process regression to estimate the mean prevalence of obesity and overweight”.

In 2015, more than 107 million children and 603 million adults were obese. They looked at time trends from 1980, and found that the prevalence of obesity doubled in more than 70 countries, and continuously increased in most other countries.

Kids have had less obesity than adults, but they’re catching up. High BMI accounted for 4.0 million deaths globally, nearly 40% of which occurred in persons who were not obese. More than

The authors estimated that “high BMI” accounted for 4 million deaths globally. This is about 7% of all deaths worldwide. More than two-thirds of these deaths were due to cardiovascular disease

About 40% of those deaths occurred in people who were overweight, but not obese.

The good news is that since we keep on improving cardiovascular care, we’re keeping up with obesity. For now. But this is an issue where getting a better handle on the problem would have benefits almost too numerable to count.

Why It’s So Hard for Insurers to Compete Over Technology

Austin and I have a piece at the JAMA Forum (it’ll also come out in an upcoming issue of JAMA itself) explaining why health plans don’t really compete with one another over the treatments that they cover.

Doing so requires good evidence on how well therapies work, but that evidence is often lacking. Insurers lack the right incentives to develop the evidence on their own because other insurers will free-ride on their efforts. And the government can’t pick up the slack because Medicare is barred from considering costs in choosing what to cover.

The law also poses an obstacle. The favorable tax treatment of employer-sponsored coverage encourages employers to offer expansive health plans. The courts are reluctant to construe contractual terms to allow insurers to refuse coverage, and they will sometimes side with “expert” opinions about medical need even where evidence of a treatment’s efficacy is lacking. And legal rules (including state coverage mandates and the ACA’s essential health benefits rule, which applies to individual and small group plans) may prohibit insurers from restricting the scope of coverage.

In principle, we could change the law to encourage plans to compete on cost-effectiveness. In practice, we doubt it would work. …

So if you’re one of those people who’d prefer a cheap plan that excludes glitzy treatments, you’re out of luck. You’ve got to buy a plan covering all medically necessary care, even if that care has little proven value or is wildly expensive.

The lack of competition between health plans interacts with the increasing market power of providers in disconcerting and under-appreciated ways, as Clark Havighurst and Barak Richman nicely explain in this 2011 paper:

At the same time that health insurance ameliorates monopoly’s usual adverse effects on output and allocative efficiency, it greatly exacerbates monopoly’s other objectionable effect, the redistribution of wealth from consumers to powerful firms. In the textbook model, the monopolist’s higher price enables it to capture for itself much of the welfare gain, or “surplus,” that consumers would have enjoyed if they had been able to purchase the valued good or service at a low, competitive price. In health care, insurance puts the monopolist in an even stronger position by greatly weakening the constraint on its pricing freedom ordinarily imposed by the limits of consumers’ willingness or ability to pay. This effect appears in theory as a steepening of the demand curve for the monopolized good or service. …

Even under orthodox theory, therefore, health insurance enables a monopolist of a covered service to charge substantially more than the textbook “monopoly price,” thus earning even more than the usual “monopoly profit.” As serious as this added redistributive effect may be in theory, however, it is rendered even more serious in practice by certain deficiencies in the design and administration of real-world health insurance. For legal, regulatory, and other reasons, … insurers … pay for any service that is deemed advantageous (and termed “medically necessary”) for the patient’s health, whatever that service may cost. Consequently, available “close substitutes” for a provider’s services do not check its market power as they ordinarily would do. Indeed, putting aside the modest effects of cost sharing on patients’ choices, the only substitute treatments or services that insured patients will accept are those they regard as perfect ones. Unlike the situation when an ordinary monopolist sells directly to cost-conscious consumers, the rewards to a monopolist selling goods or services purchased through health insurance may easily and substantially exceed the aggregate consumer surplus that patients would derive at competitive prices.

Discussions of antitrust issues in the health care sector rarely, if ever, explicitly observe how health insurance in general or U.S.-style insurance in particular enhances the ability of dominant sellers to exploit consumers. … Yet, the effect we identify has potentially huge implications for consumers and the general welfare and thus for antitrust analysis not only of hospital mergers but also of other actions or practices capable of enhancing provider or supplier market power.

Monopoly in any market is bad. In the health care market, however, the presence of insurance—and especially insurance that is insensitive to the value of the treatments that it covers—makes monopoly much worse.

Marketplace interview

NPR’s Marketplace aired an interview with me yesterday about reading statutes and about the Senate health care bill in particular.

Kai Ryssdal: Let me, first of all, ask you how you think about reading these bills. Because you are not a lay person in this field, you have some expertise. So how do you go about it?

Nicholas Bagley: Well, it’s hard. These bills are the latest layers that are added on top of many, many other bills that have come before in the health care space. And so when you read a bill, what you have to do is have all the bills that came before at hand so you understand when they say, “We’re amending subsection A of subparagraph one,” you know what that’s referring to.

I should’ve added that just reading a bill is a pretty terrible way to understand it. Even for experts, the complicated cross-references, hyper-technical language, and mind-numbing boredom of the exercise are serious impediments to understanding.

Far better, instead, to first read plain-language descriptions of what the bill is supposed to do. Once you understand that, then try reading the portions of the bill that you really care about. You’ll be in a much better position to understand how the bill actually does what it claims to do—and how it might fall short.

July 5, 2017

It was supposed to get easier for adolescents to get emergency contraception. It didn’t.

One of the best parts of my job is that I get to mentor a large number of junior faculty in the school of medicine. So many of them are inspiring. One (Tracey Wilkinson) had a paper published this week* that deserves attention. “Access to Emergency Contraception After Removal of Age Restrictions“:

BACKGROUND: Levonorgestrel emergency contraception (EC) is safe and effective for postcoital pregnancy prevention. Starting in 2013, the US Food and Drug Administration removed age restrictions, enabling EC to be sold over the counter to all consumers. We sought to compare the availability and access for female adolescents with the 2012 study, using the same study design.

METHODS: Female mystery callers posing as 17-year-old adolescents in need of EC used standardized scripts to telephone 979 pharmacies in 5 US cities. Using 2015 estimated census data and the federal poverty level, we characterized income levels of pharmacy neighborhoods.

In 2013, you may remember, the FDA removed age restrictions from emergency contraception so that it could be sold over-the-counter to anyone having sex. I wrote about this issue a number of times. She set up “secret shoppers” to call pharmacies and ask them about EC access. Sometimes they shoppers pretended to be adolescents. Sometimes they were doctors.

Tracey had done a study on access to EC by adolescents (I highlighted her work in an Upshot column) in 2012. She repeated her study in 2015 to see if the new regulations made a difference.

Of the 979 pharmacies contacted, 83% indicated that EC was available for purchase. That hadn’t much changed over time. Neither had many of the barriers to getting EC in a timely way. Pharmacies in low-income neighborhoods were still the most likely to report that it was impossible to obtain EC access under any circumstances. Almost half still reported misinformation on who could get EC access over the phone.

In other words, they were still too-likely to tell adolescents it wasn’t over-the-counter or they weren’t old enough to get it.

Most pharmacies carry emergency contraception. But we still haven’t cleared the hurdles necessary to help adolescents get access to it. There’s much more work to be done.

*In the interests of full disclosure, I am also an author of this paper. Feel free to get angry at me for the imperfections. All credit goes to Tracey, though.

Nursing homes and mandatory arbitration

Emboldened by a string of aggressive Supreme Court decisions, businesses are increasingly turning to arbitration to shield themselves from civil litigation. Odds are, for example, that you’ve signed away your right to sue your cell phone carrier and cable company. Not that you noticed. You just clicked “yes” when asked if you’d read pages of stultifying boilerplate. Or check out your employment contract: workers are increasingly being asked to forgo their right to sue when they take a job.

Arbitration does have its advantages. It’s cheaper and faster than civil litigation, and arbitrators can be selected who have some relevant expertise. In a competitive market, the benefits of arbitration should accrue to consumers in the form of lower prices.

But the extraordinary growth of mandatory arbitration over the past couple of decades is one of the more unnerving developments in modern American law. Genuine consent to arbitration is often fictional. Arbitrators tend to favor the repeat players who hire them—companies, not consumers. Arbitration agreements can forestall class action lawsuits, making it difficult or impossible to hold companies to account for small-in-size but widespread injuries. And where civil litigation can shine a light on shoddy business practices, arbitration is shrouded in secrecy.

* * *

In October 2016, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) decided to push back on mandatory arbitration. By rule, CMS adopted a novel “condition of participation” for Medicare and Medicaid. Nursing homes that participate in the programs—which is to say, all nursing homes—could no longer ask their residents to sign away their right to sue upon entering the nursing home. (The rule covered only pre-dispute arbitration; residents could still agree to arbitration once a dispute arose.)

Why? As CMS explained, the elderly residents of nursing homes will typically lack the capacity to sign away their rights. Many have some form of dementia, and a much higher percentage will be physically disabled or emotionally overwhelmed. Even if adult children actually sign the paperwork, they usually don’t have powers of attorney—and, given the stress and difficulty of moving mom into a nursing home, they may not be in much of a position to negotiate, either. Plus, geographic and financial constraints will often give nursing homes substantial bargaining power.

Beyond that, waiving the right to sue raises safety concerns. Nursing homes are notoriously prone to quality problems, and those problems can have devastating consequences. Tort law is one way—albeit not the only way, and not necessarily the best way—to hold nursing homes to account for their negligence. If nursing homes can shield themselves from lawsuits, they might take worse care of their residents.

* * *

Predictably, the nursing home industry sued, arguing that the rule exceeded CMS’s authority. In November, a federal judge in Mississippi sided with the plaintiffs, and entered a preliminary injunction prohibiting CMS from applying the rule. The agency promptly appealed. In the meantime, for reasons I don’t fully understand—and perhaps for no good reason at all—the agency chose not only to comply with the ruling in Mississippi, but across the country.

Then President Trump took office. In early June, with little fanfare or notice, the administration dismissed the appeal and proposed to undo the change altogether. “Upon reconsideration, we believe that arbitration agreements are, in fact, advantageous to both providers and beneficiaries because they allow for the expeditious resolution of claims without the costs and expense of litigation.” The comment period is open through August 7, and the rule is likely to be finalized in 2018.

With health reform dominating the news, this volte-face has been overlooked. That’s a shame: it’s a big deal, for reasons I’ll explore over the next few weeks in a series of posts. What does the research say about civil litigation and nursing home safety? Can nursing home residents really make informed decisions about surrendering their constitutional right to a jury trial? And is it true that CMS lacks authority to regulate arbitration agreements?

Medicaid Worsens Your Health? That’s a Classic Misinterpretation of Research

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2017, The New York Times Company). It was coauthored by Aaron Carroll and Austin Frakt.

As a program for low-income Americans, Medicaid requires the poor to pay almost nothing for their health care. Republicans in Congress have made clear that they want to change that equation for many, whether through the health bill that is struggling in the Senate or through future legislation.

The current proposal, to scale back the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion and to cap spending each year, would give incentives to states to drop Medicaid coverage for millions of low-income Americans. It would offer tax credits toward premiums for private coverage, but those policies would come with thousands of dollars in new deductibles and other cost sharing. Despite the much higher out-of-pocket costs, some policy analysts and policy makers argue that low-income Americans would be better off.

To take one highly placed example, Seema Verma, the leader of the agency that administers Medicaid, recently cited studies questioning the program’s effectiveness and wrote that the health bill “will help Medicaid produce better results for recipients.”

What is the basis for the argument that poor Americans will be healthier if they are required to pay substantially more for health care? It appears that proponents like Ms. Verma have looked at research and concluded that having Medicaid is often no better than being uninsured — and thus that any private insurance, even with enormous deductibles, must be better. But our examination of research in this field suggests this kind of thinking is based on a classic misunderstanding: confusing correlation for causation.

It’s relatively easy to conduct and publish research that shows that Medicaid enrollees have worse health care outcomes than those with private coverage or even with no coverage. One such study that received considerable attention was conducted at the University of Virginia Health System.

For patients with different kinds of insurance — Medicaid, Medicare, private insurance and none — researchers examined the outcomes from almost 900,000 major operations, like coronary artery bypass grafts or organ removal. They found that Medicaid patients were more likely than any other type of patient to die in the hospital. They were also more likely to have certain kinds of complications and infections. Medicaid patients stayed in the hospital longer and cost more than any other type of patient. Private insurance outperformed Medicaid by almost every measure.

Other studies have also found that Medicaid patients have worse health outcomes than those with private coverage or even those with no insurance. If we take them to mean that Medicaid causes worse health, we would be justified in canceling the program. Why spend more to get less?

But that is not a proper interpretation of such studies. There are many other, more plausible explanations for the findings. Medicaid enrollees are of lower socioeconomic status — even lower than the uninsured as a group — and so may have fewer community and family resources that promote good health. They also tend to be sicker than other patients. In fact, some health care providers help the sickest and the neediest to enroll in Medicaid when they have no other option for coverage. Because people can sign up for Medicaid retroactively, becoming ill often leads to Medicaid enrollment, not the opposite.

Some of these differences can be measured and are controlled for in statistical analyses, including the Virginia study. But many other unmeasured differences can skew results, even in studies with such statistical controls. The authors of the U.V.A. surgical study and of studies like it know this, and say as much right in their papers. They practically shout that the correlations they find are not evidence of causation.

That hasn’t stopped policy makers and others in the media from asserting otherwise.

Other approaches to studying Medicaid more credibly demonstrate the value of the program. The most straightforward way is a prospective randomized trial, which gets around the subtle biases that plague studies that use only statistical controls. There has been exactly one randomized study of Medicaid, focused on an expansion of the program in Oregon.

Because demand for the program exceeded what Oregon could fund, in 2008 the state introduced a lottery for Medicaid eligibility. A now famous analysis took advantage of this lottery’s randomness, finding that Medicaid increased rates of diabetes detection and management, reduced rates of depression and lowered financial strain. It did not detect improvements in mortality or measures of physical health, but it did not have enough sick patients or enough time to detect differences we might have expected to see. In other words, it was not powered to detect changes in mortality or physical health.

Saying that this study proves Medicaid doesn’t work ignores this limitation. Regardless, there was nothing to indicate that having Medicaid worsened health.

Another way to tease out the causal effect of Medicaid is to look at variations in Medicaid eligibility rules across states. With respect to health outcomes, these state decisions are effectively random, so they act like a natural experiment. Older studies based on this approach, using data from the 1980s and 1990s, have not found that Medicaid causes worse health.

Findings from more recent studies looking at expansions in enrollment, in the 2000s and then under the Affordable Care Act in 2014, are consistent with older ones. One can argue that Medicaid can be improved upon, but the credible evidence to date is that Medicaid improves health. It is better than being uninsured.

Here’s another telling way to test the idea that Medicaid is harmful. Some of the studies that associate Medicaid with worse health, as compared with private insurance, also find the same association with Medicare. No one argues that Medicare is making people sick.

A very recent New England Journal of Medicine review by Ben Sommers, Atul Gawande and Kate Baicker found that Medicaid increases patients’ access to care and leads to earlier detection of disease, better medication adherence and improved management of chronic conditions. It also provides people with peace of mind — knowing that they will be able to afford care when they get sick.

Research is clear on how people react when asked to pay more for their health care, as the Senate would ask many of those now on Medicaid to do. As the Congressional Budget Office reported, many poor people would choose not to be covered, because even if they could afford the premiums with help from tax credits, deductibles and co-payments would still be prohibitively expensive. No studies prove that removing millions from Medicaid in this way would “produce better results for recipients,” at least as far as their health is concerned.

July 4, 2017

What studies should I write about?

From time to time I solicit suggestions on what to write about. Usually I solicit topics, but that often doesn’t generate very many ideas I can work with. The reason is that my writing isn’t driven by topics so much as studies.

Of course, each piece is on a topic. But my entry is through the research. I start with a study that sparks an idea I think will resonate with people. That leads to other studies, and a post is born.

With that, what studies do you think I should write about? Please send links or full enough citations so I can find them. You can reach me on Twitter, by email, or in the comments below, which are open for one week.

Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers