Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 128

July 27, 2017

Healthcare Triage: Marathons Kill People, but not Usually Runners

I’m still traveling but Healthcare Triage never stops. This week’s episode:

This episode was adapted from a column I wrote for the Upshot. Links to sources and further reading can be found there.

Democracy, Deliberation, and the Congressional Health Care Votes

At The Incidental Economist we write about the consequences of health policy: how it affects health, spending, and the like. In this post, however, I want to reflect on the process whereby the 115th Congress has considered legislation to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act. My view is that Congressional leaders have abused the legislative process during the consideration of these bills. This abuse has weakened Congress as a deliberative body and damaged American democracy.

What do I mean by deliberation and how have norms of deliberation been abused?

The requirement that laws should be deliberated is just the expectation that legislators will offer reasons for the laws they propose. In a democracy, we expect that such deliberation will be public and this, in turn, means that the laws must be accessible to other legislators and to citizens. You can’t reason about a law that you can’t see.

In its attempts to repeal the ACA, the Congressional leadership has consistently abused the norm that proposed laws should be accessible and deliberated in public. The House and the Senate have held no hearings on the bills to repeal and/or replace the ACA. The bills have been drafted in secret and hidden from scrutiny until the last possible moments, making it impossible to discuss their contents. When they could, sponsors have attempted to obtain votes before the bills were analyzed by the Congressional Budget Office. On July 25th, the motion to proceed on the Better Care Reconciliation Act was passed without any Senator or any citizen knowing the content of the bill that they were about to debate. Until July 26th, the bills have been considered without opportunities for legislators to introduce amendments. Here is Bill Kristol, no friend of liberal health care bills:

If GOP votes to proceed to a bill w/ no text, no hearings, no CBO score, no clarity on Byrd rule, they deserve the fiasco they’re inviting.

— Bill Kristol (@BillKristol) July 25, 2017

The deliberation of the ACA-repeal bills has been limited by design. These bills are strikingly unpopular, with public approval rates in the low twenties or teens. The sponsors have hidden the bills from scrutiny because they know that the more these bills are discussed the less chance they have of passing.

But why should anyone care about legislative process? Jaded realists say that what matters is what gets passed, not how, and that only losers care about process.

The jaded realists are dangerously wrong. Deliberative process matters for two reasons.

First, we’re less likely to make good policy decisions without public deliberation. Of course, democracies have often made terrible, tragic decisions. Nevertheless, if neither citizens nor legislators know the content of legislation, they’re less likely to make decisions that cohere with either facts about the world or the values of citizens.

Second, if our governing processes abuse even minimal requirements of rational deliberation, we do not have a democracy. Democracy is valuable for its own sake, not just because it promotes better decisions. Democracy means that we all participate as equals in making the decisions that concern us. This cannot happen if the proposed laws are inaccessible. Amy Guttman and Dennis Thompson argue that in a democracy,

Persons should be treated not merely as objects of legislation, as passive subjects to be ruled, but as autonomous agents who take part in the governance of their own society, directly or through their representatives. In deliberative democracy an important way these agents take part is by presenting and responding to reasons, or by demanding that their representatives do so, with the aim of justifying the laws under which they must live together. The reasons are meant both to produce a justifiable decision and to express the value of mutual respect. It is not enough that citizens assert their power through interest-group bargaining, or by voting in elections… Assertions of power and expressions of will, though obviously a key part of democratic politics, still need to be justified by reason. When a primary reason offered by the government for going to war turns out to be false, or worse still deceptive, then not only is the government’s justification for the war called into question, so also is its respect for citizens.

The abuse of legislative process undermines the moral core of democracy, which is the mutual respect of equal citizens.

July 26, 2017

Finding the signal in the noise of hospital quality metrics

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2017, The New York Times Company).

The relatively recent movements toward transparency and quality in health care have collided to produce dozens of publicly available hospital quality metrics. You might consider studying them in advance of your next hospital visit. But how do you know if the metrics actually mean anything?

There are valid reasons to be suspicious of measurements of hospital quality. One longstanding concern is that some hospitals may disproportionately attract sicker patients, who are more likely to have worse health outcomes. That could cause those hospitals to appear less effective than they actually are. Statistical techniques can mitigate but not completely eliminate this bias.

A related problem is that measurement of the quality of a hospital can be biased if it doesn’t take into account the socioeconomic status of the population it serves — and many such metrics do not. For example, a hospital in a wealthy region serves patients with more resources, relative to a hospital in a poorer region. If greater patient resources translate into better health — and a lot of research suggests they do — the hospital in the wealthy region may appear to be of higher quality. But that isn’t necessarily because of the care it delivers.

Because of issues like these, one study found that approaches to rating hospitals don’t agree on which hospitals are high or low in quality. “We have a vast number of quality measures,” said Dr. Ashish Jha, a co-author of the study and a scholar of health care quality at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, “but which are signal and which are noise? It can be incredibly tricky to sort out.”

A recent study, however, shows that there is at least a bit of signal within the noise. The study, by health economists at M.I.T. and Vanderbilt, found that hospitals that score better on certain metrics reduce mortality. Among the ones they examined were patient satisfaction scores.

“We found that hospitals’ patient satisfaction scores are useful signals of quality, which surprised me to some extent,” said Joseph Doyle, an economist at M.I.T. and one of the study’s authors. “Hospitals with more satisfied patients have lower mortality rates, as well as lower readmission rates.”

According to the study, a hospital with a satisfaction score that is 10 percentage points higher — 70 percent of patients satisfied versus 60 percent, for example — has a mortality rate that is 2.8 percentage points lower and a 30-day readmission rate that is 1.9 percentage points lower. This is consistent with earlier work, described by my colleague Aaron Carroll, that found an association between better Yelp ratings of hospitals and lower mortality rates and readmission rates for certain conditions.

Mr. Doyle’s study, published as a National Bureau of Economic Research working paper, is exceedingly clever in its design. The ideal study would be to randomly assign patients needing hospital care to facilities with high or low quality. Then, this ideal study would see what happened to those two groups of patients: Did the group randomized to more highly rated hospitals live longer and stay out of the hospital longer? If so, the metrics are, in fact, providing useful guidance.

For ethical as well as practical reasons, we cannot randomly assign patients to hospitals. But it turns out that in emergency situations, like heart attacks, which ambulance service picks up patients who live in the same neighborhood is effectively random in many cases.

In some locations, patients are assigned to services in an orderly rotation. In others, services compete to see which can reach a patient first. In others still, it’s the ambulance that happens to be closest to the patient that gets the business. In all of these cases, exactly which ambulance picks up a given patient with a given condition is random. It also turns out that ambulance companies have preferences for certain hospitals, and the random assignment of ambulance companies to patients leads to an effectively random selection of the hospital at which they receive care.

The authors exploited this randomness as a natural experiment to test how different kinds of hospital quality measures predicted mortality and readmissions. Using data from 2008 to 2012, they compared Medicare patients needing emergency care who lived in the same ZIP code but were served by different ambulance companies and, therefore, tended to be delivered to different hospitals with different quality scores. The approach was validated in earlier research that showed that higher-cost hospitals have lower mortality rates than lower-cost ones.

In addition to testing the predictive ability of satisfaction scores, Mr. Doyle’s study examined indicators of high-quality care — things that a hospital does that are believed to improve outcomes, like the rate at which a hospital gives heart attack patients aspirin upon arrival.

Here, too, hospitals with better such indicators had lower mortality and readmission rates. The very best hospitals by these measures can reduce the odds of death within a year by 14 percent relative to the very worst hospitals, for example.

“Though hospital quality measures are not perfect, our work provides some reasons to be optimistic about some of them,” Mr. Doyle said. “Hospitals that score well on patient satisfaction, follow good processes of care and record lower hospital mortality rates over the prior three years do seem to keep patients alive and out of the hospital longer.”

July 24, 2017

Arbitration can obscure safety problems in nursing homes

This is the third post in a series on a proposed CMS rule that would eliminate an Obama-era ban on pre-dispute arbitration for nursing home residents. For the intro, see here .

As I explored in my last post, the research suggests that malpractice law doesn’t much improve the quality of care in nursing homes. If that’s right, then maybe it doesn’t pose safety risks to allow nursing homes to include arbitration clauses in their admissions contracts.

But that conclusion may be too hasty. The available studies investigate how malpractice lawsuits directly change the behavior of nursing homes. They don’t purport to study how tort law, by highlighting endemic safety problems, can mobilize a policy response.

Consider just one example. In 1986, the Institute of Medicine released a landmark report (“Improving the Quality of Care in Nursing Homes”) prompted in part by litigation in which nursing home residents “proved a variety of violations of regulatory standards, including theft of personal funds, overuse of psychotropic drugs, inadequate care resulting in decubitus ulcers, inadequate skin and nail care, inadequate bowel assistance, and sanitation problems.” That report led directly to the adoption of the Nursing Home Reform Act, which imposed minimum safety requirements and instituted mandatory inspections. The research indicates that these changes led to substantial improvements in nursing home quality. Without malpractice litigation, those improvements may never have come to pass.

Quality remains depressingly low, however, as a follow-up report in 2000 concluded. That report, too, was prompted in part by litigation. “Concerns about problems in the quality of long-term care persist despite some improvements in recent years, and are reflected in, and spurred by, recent government reports, congressional hearings, newspaper stories, and criminal and civil court cases.” No one today thinks that we’ve addressed the concern. As Rachel Werner and Tamara Konetzka noted in a 2010 piece in Health Affairs, “ongoing quality problems and the large number of nursing home residents at risk have kept nursing home quality under scrutiny for decades.” A recent, eye-opening exposé from Jordan Rau at Kaiser Health News and the New York Times details how federal oversight of nursing homes is failing to grapple with rampant quality deficiencies.

Lawsuits are public, and often include the sorts of graphic, shocking details that draw press attention and public outrage. For one example, drawn from a law review article by Lisa Tripp:

Mrs. Sauer was often times found wet without being changed in four hours. She had pressure sores on her back, lower buttock, and arms on days she was found sitting in urine and excrement. A former staff member remembered seeing Mrs. Sauer at one time with a pressure sore the size of a softball, which was open. Her sores and blisters became infected. She was frequently double-padded, and even triple-padded, rather than single-padded for her incontinence problems. At times, she had no water pitcher in her room; nor did she receive a bath for a week or longer, due to there not being enough staff at the facility. She was described as “always thirsty” and her nursing notes indicated that she was heard moaning and crying. At the time she was hospitalized prior to her death, she had a severe vaginal infection. When she was in the geriatric chair, she was not “let loose” every two hours, as required by law. Finally, Mrs. Sauer was found to suffer from poor oral hygiene with caked food and debris in her mouth.

These details only emerged because Mrs. Sauer’s family filed a lawsuit. If the Sauers had been forced into arbitration, Tripp writes, “[t]he chilling description … would have disappeared from public consciousness.”

That secrecy may matter more than is commonly assumed. In an important book, Making Rights Real, Charles Epp examines the role that tort law played in getting police departments, employers, and park administrators to address longstanding problems in the 1980s and 1990s:

Police departments created strict policies on the use of force and cracked down on abusive officers. Government human relations departments created and strictly enforced policies prohibiting sexual harassment. Parks administrators tore out and replaced play equipment in tens of thousands of playgrounds, designing and managing the new installations to reduce the risk of injury. I argue that these developments, and many more, came about because newly energized activist movements and liability lawyers forced agencies to face up to long-ignored problems of abuse and injury, and because managers came to recognize that these legal claims represented fundamental threats to their public and professional legitimacy.

One of Epp’s most striking conclusions is that the financial penalties associated with tort judgments were too small to have driven the changes. What mattered, instead, was the bad publicity associated with lawsuits—and the concomitant damage to professional legitimacy. That legitimacy threat was the “engine of pressure,” not money.

Now, nursing homes aren’t government bureaucracies like the ones that Epp studied. But they’re closer than you might think. They’re dependent on public funding and they’re exquisitely attuned to the risk that public outrage could erode support for that funding. They also recognize that the outrage could lead to enhanced oversight. No less than police departments, nursing homes have an interest in avoiding threats to their professional integrity.

A pre-dispute arbitration agreement is one technique for avoiding those threats. But it’s a technique that leaves the underlying quality problems to fester like a bedsore.

I don’t want to overstate the case. Malpractice litigation isn’t the only way that quality problems come to light, and not all nursing homes insist on pre-dispute arbitration. (In 2011, Tripp found that 43% of North Carolina nursing homes, including all of the largest nursing-home chains, included pre-dispute arbitration agreements in their admissions contracts.) Plus, even if shifting from litigation to arbitration hampers the campaign to improve nursing home quality, the costs of litigation might still outweigh its benefits.

But I will confess to disquiet. The deplorable quality of care in many nursing homes is a national crisis, even if it doesn’t show up on the front page every day. Is now really the time to give the industry another tool to shield its conduct from public scrutiny?

July 19, 2017

Can Psychedelics Be Therapy? Allow Research to Find Out

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2017, The New York Times Company).

In the last few years, calls for marijuana to be researched as a medical therapy have increased. It may be time for us to consider the same for psychedelic drugs.

Two general classes of such drugs exist, and they include LSD, psilocybin, mescaline and ecstasy (MDMA).

All are illegal in the United States because they carry a high risk of abuse. They can also cause harm. The best-known adverse event is persistent flashbacks, though these are believed to be rare. More common are symptoms like increased heart rate and blood pressure, anxiety and panic.

Some people have pointed to anecdotal evidence of positive effects. Ayelet Waldman, a novelist and former federal public defender, wrote a memoirabout how microdosing of the drugs turned her life around. But these drugs — like all drugs — carry risks that should not be ignored. With plenty of potential downsides, and no proven upsides, it’s not surprising that such drugs have been shunned.

In recent years, however, research has begun to show promise in treating a number of ailments.

People with life-threatening illnesses can also suffer from anxiety, which is hard to treat, especially when patients are on many other medications. In 2014, a small randomized controlled trial was published that examined if LSD could be used to improve this anxiety. The treatment included two LSD-assisted psychotherapy sessions conducted two to three weeks apart. Anxiety was significantly reduced in the intervention group for up to a year. Such results, however, could have been due in part to a placebo effect.

More common are studies of the use of psychedelics to treat abuse or addiction to other substances. A 2012 meta-analysis of studies exploring LSD’s potential to treat alcoholism looked at six randomized controlled trials. They included more than 500 patients, with follow-up of three to 12 months. The interventions usually involved one dose of LSD, given in a supervised setting, coupled with therapy. Alcohol use and misuse were significantly reduced in the LSD group for six months; differences seemed to disappear by one year. Similar studies using psilocybin have also shown promising results.

There was an open label study — meaning there’s no placebo or attempt to mask treatment information — of three doses of psilocybin as part of a tobacco cessation program. It found that 12 of 15 participants (who had smoked an average of more than 30 years) remained abstinent six months after the program began and 16 weeks after their last treatment. That’s a much higher rate than seen in traditional programs to help people quit smoking.

Other uses might exist as well. Researchers examined the potential for MDMA in the treatment of chronic and treatment-resistant post-traumatic stress disorder. At two months after therapy, more than 80 percent of those in the treatment group saw a clinical improvement versus only 25 percent of those in the placebo group. These researchers later followed up with participants in the study, and found that the beneficial effects lasted for at least four years, even with no further treatment with psychedelics. Similar studies have also seen improvements in symptom scores.

As with marijuana, though, studies like these are the exception, not the rule. It is very, very difficult to do research on psychedelic compounds because they, like pot, are classified as Schedule I controlled substances, meaning they have a very high potential for misuse and no accepted uses. Schedule II drugs also have a high potential for abuse, but are considered to have potential benefits. These include OxyContin, fentanyl, Percocet and even opium.

To engage in research in Schedule I drugs, scientists have to get approval from the Drug Enforcement Administration. To obtain a license, research labs must have inspections to prove that they are capable of storing the drugs and protecting them from misuse. In Britain, the added costs of licensing and security can cost a lab about £5,000 a year, or nearly $6,500. Unfortunately, the costs in the United States are not as well documented.

Because of this, much of the research on these drugs is old; a lot of it took place before the United States and other countries categorized these drugs in the 1960s. What research has occurred since has often taken place in countries that are more permissive in their experiments.

Given the potential dangers inherent in these drugs, it’s important to stress that research would need to be closely monitored. Although the drugs are relatively safe compared with substances like heroin or cocaine, and aren’t nearly as addicting, they still pose psychological and physical risks.

People with a family or personal history of psychotic or psychiatric disorders should be particularly wary, and perhaps be excluded from trials. Research requires safety monitoring, careful planning and significant support throughout. We need to watch carefully for adverse outcomes, both expected and unexpected. We need to make sure protocols are transparent and reproducible.

We also need to acknowledge that we need more research before anyone attempts to use these drugs as medicine. They’re typically coupled with professional therapy in studies, and we still aren’t sure there are benefits.

But it may be time to time to reconsider our current classification of controlled substances. Clearly we must continue to be vigilant about whether drugs pose physical harm to patients. But we could assess drugs using additional measurements, including the potential for dependence; social costs through damaged family and social life; and financial costs through health care, social care and the need for police involvement.

Using these metrics, it’s hard to argue that alcohol and tobacco should be legal for adults while marijuana and psychedelics should be considered so dangerous they’re hard to study. Likewise, opioids are considered widely acceptable in practice, yet appear to do far more harm.

With the potential to help curb more serious addictions and ease the symptoms of mental illnesses, it seems odd to continue to make it nearly impossible to research the therapeutic potential of psychedelics.

Seriously? Still with the Vitamin D?

This time they’re trying to prevent upper respiratory infections in kids. I swear, I have no idea who thinks this stuff up. “Effect of High-Dose vs Standard-Dose Wintertime Vitamin D Supplementation on Viral Upper Respiratory Tract Infections in Young Healthy Children“:

Importance: Epidemiological studies support a link between low 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and a higher risk of viral upper respiratory tract infections. However, whether winter supplementation of vitamin D reduces the risk among children is unknown.

Objective: To determine whether high-dose vs standard-dose vitamin D supplementation reduces the incidence of wintertime upper respiratory tract infections in young children.

Design, Setting, and Participants: A randomized clinical trial was conducted during the winter months between September 13, 2011, and June 30, 2015, among children aged 1 through 5 years enrolled in TARGet Kids!, a multisite primary care practice–based research network in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Interventions: Three hundred forty-nine participants were randomized to receive 2000 IU/d of vitamin D oral supplementation (high-dose group) vs 354 participants who were randomized to receive 400 IU/d (standard-dose group) for a minimum of 4 months between September and May.

Main Outcome Measures: The primary outcome was the number of laboratory-confirmed viral upper respiratory tract infections based on parent-collected nasal swabs over the winter months. Secondary outcomes included the number of influenza infections, noninfluenza infections, parent-reported upper respiratory tract illnesses, time to first upper respiratory tract infection, and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels at study termination.

We start, of course, with the epidemiological data that low levels of Vitamin D are associated with higher risks of URIs. I can’t find the absolute risk in the paper, and I’m too tired to go look myself. I assume it’s statistically significant, although I reserve the right to snarkily assume it’s clinically insignificant and probably confounded.

Anyway, it doesn’t matter, because here is the RCT to test the association for causation. Researchers gathered kids age 1-5 years in the winters from 2011-2015 in Canada. They randomized them to get either 2000 IU/d or 400 IU/d of Vitamin D, because I suppose it would be criminal not to supplement everyone with at least some Vitamin D these days. The main outcome of interest was laboratory-confirmed viral URI. Secondary outcomes included individual infections and Vitamin D levels.

More than 700 kids took part in this study, and nearly all completed it (well done, researchers). In the high-dose group, kids got an average 1.05 infections, and in the standard-dose group they got 1.03 infections. Fewer with less Vitamin D, but not statistically significant. There was also no significant differences in the median time to the first laboratory-confirmed infection or the number of parent-reported URIs between groups.

When the study ended, the group getting high-dose Vitamin D had levels of 48.7 ng/mL while the standard-dose group had levels of 36.8 ng/mL, although I’m still unclear on why we should care. The IOM says that anything over 20 ng/mL is “Generally considered adequate for bone and overall health in healthy individuals” and when you get over 50 ng/mL “Emerging evidence links potential adverse effects to such high levels”.

I do not understand why we keep looking for Vitamin D to be some sort of wonder drug. It’s seriously baffling to me.

July 18, 2017

Healthcare Triage: New Studies Adjust Our Thinking on Spinal Manipulation

This episode was adapted from a column I wrote for the Upshot. Links to sources and further reading can be found there.

Marketplace networks

Daniel Polsky, Yuehan Zhang, Laura Yasaitis, and Janet Weiner of Penn’s Leonard Davis Institute have been doing the foundational work of tracking and analyzing marketplace plans’ network extent. Late last year, they published a Data Brief on the state of marketplace plans’ networks in 2016, with comparison to findings from 2014.

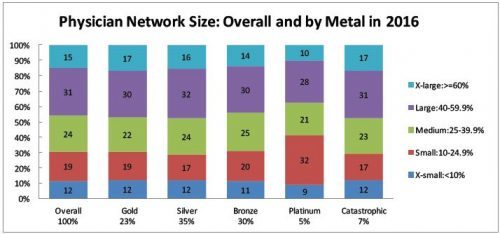

For each marketplace plan, they quantified network size as the ratio of the number of participating physicians to the number of physicians eligible to participate in the plan’s service area. They did this for all physicians and by specialty. They categorized network extent as follows:

x-small:

small: 10%-25% of physicians participating

medium: 25%-40% of physicians participating

large: 40%-60% of physicians participating

x-large: ≥60% of physicians participating

Across all plans and marketplaces, 12% of networks are x-small, 19% are small, 24% are medium, 31% are large, and 15% are x-large. That’s a lot of numbers. Since consumers, wonks, and policymakers are probably most concerned about narrow networks, it may be simpler just to pay attention to the proportion that are either x-small or small: 31%.

According to their analysis, for the most part, there is little correlation between network extent and metal tiers. As shown in the chart below, within metal tier, the distribution of plans’ network extent is fairly stable. The one exception is platinum plans, which have a substantially higher proportion of narrow networks, with 41% x-small or small. However, platinum plans only attract 5% of enrollees.

The Data Brief also breaks down network extent by physician specialty. Prior work suggests that narrow network plans help control health care spending so long as they don’t disrupt access to primary care physicians (PCPs) and do reduce network extent of specialists. The 2016 results show that network extent across primary care and other specialists is largely similar.

There are two exceptions. First, networks for psychiatrists tend to be much more narrow (45% x-small or small) than other specialists (e.g., 31% x-small or small for PCPs). This raises concerns about adequate access to mental health care in marketplace plans. Second, hospital-based physician networks are extremely narrow: 72% x-small or small. As the authors point out, “This is notable given that this is the group of physicians most likely to lead to a surprise out-of-network bill.”

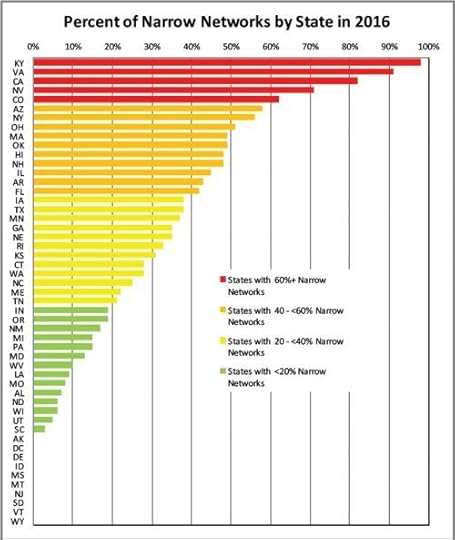

Network extent varies tremendously by state. The chart below shows the percent of networks in each state that are x-small or small. It would be valuable to understand what accounts for such variation and its implications. How does it relate to provider and insurer market power, for example? What patterns of care and outcomes correlate with network extent? I’d also like to know how geographic variation of network extent looks by specialty, again with the implications for access and health care outcomes.

If you’re concerned about narrow networks, you might want to know how their prevalence has evolved over time. The authors compared network extent from 2014 to 2016 for silver-rated plans. By and large, the proportion of narrow network plans didn’t change, though there was a shift from small networks (declining from 31% to 29%) to x-small networks (increasing from 6% to 12%).

You’ll find even more stats in the Brief. Though the Leonard Davis Institute investigators have made aggregate marketplace network extent more transparent to policymakers and the public, making network extent — including within specialty — transparent to consumers at the time of plan purchase is an ongoing challenge. Also particularly troubling is

[t]he high prevalence of narrow networks among hospital-based physicians […]. Given that these physicians are the ones most likely to send surprise out-of-network bills, this remains a concern for those with narrow network plans and broad plans.

July 17, 2017

Medicaid by the numbers

All of this is cribbed from a Viewpoint today in JAMA by Ben Sommers and David Grabowski.

Medicaid beneficiaries in 2017:

Total: 77 million people

Kids: 34 million

Elderly: 6 million

Blind and disabled: 9 million

Pregnant women: 2 million

Parents and childless adults: 27 million

For those of you keeping track at home, this means that only 35% of beneficiaries aren’t kids, old, blind, disabled, and/or pregnant. Remember that when people should say that Medicaid recipients should “try harder”. Also, of that 35%, many already have jobs. Some are stay-at-home parents. So the number of people who could “try harder” isn’t as many as lots of people think.

Under the ACA, it’s projected that 86 million beneficiaries would exist in Medicaid. If repeal and replace happens, it would go down to 77 million.

Share of spending (2014)

Kids: 19%

Elderly: 21%

Blind and disabled: 40%

Parents and childless adults: 19%

And if you cut, where will it come from? Pregnant women are included in the 19% of parents and childless adults. There’s not that much fat. So do you cut care for kids? For the blind and disabled? For the elderly?

The numbers don’t add up easily. There’s no magic here. People will get “sent” to private plans with huge deductibles. It won’t be better.

July 14, 2017

Healthcare Triage Breaking News: The Senate and Obamacare, Part Deux

The Senate is trying once again to repeal and replace Obamacare, and we’ve got the news on what’s in the updated bill. Spoiler Alert: not much has changed. There are still big cuts to Medicaid, and some small changes to the proposed tax cuts of their previous bill.

We’re trying to make HCT News more “newsy”. Hope you like it!

Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers