Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 125

September 1, 2017

Help me learn new skills in 2017 – Hebrew!

This post is part of a series in which I’m dedicating two months to learning six new skills this year. The full schedule can be found here. This is month seven/eight. (tl;dr at the bottom of this post)

Yeah. I’m an idiot. You can’t learn a new language in two months. I mean, maybe you can if you go immerse yourself in another place where it’s all you hear and speak all day. But as part of your already overloaded life? Not going to happen.

That didn’t stop me from trying.

After a lot of investigation, I went with Rosetta Stone. I paid for the online version, because that would let me work on all my devices, no matter where I was. I committed to 30 minutes to an hour each day.

I should state that – for the record – I can already read Hebrew fluently. As part of the strange childhood education many Jews in America receive at Sunday and Hebrew school – I can read the language very well, without any idea what I’m reading. Very strange, but also very common. This would have been much harder if I also had to learn the alphabet. The program was prepared for this, though, and offered an option where it assumed I was already literate.

If you haven’t used Rosetta Stone before, it’s pretty well thought out. There are overarching lessons that have a general theme. Each of these is broken up into four units. Each unit has 7-8 components. The general way it works is to present you with four pictures and then – and this varies – get you to make choices based on cues. Sometimes the program speaks to you, and you have to pick the right picture. Sometimes, it shows you words, and you have to pick right. Sometimes, based on the pictures, you have to choose words, and sometimes you have to speak.

The voice recognition is generous. I was often way off, and it judged me correct, but I was ok with that. You can change the setting (I didn’t).

One of the frustrating, but also satisfying, aspects was that they just drop you into the beginning of each unit. No list of vocabulary words to learn. They just show you new pictures. Based on old words you already know (man/boy/woman/girl) you have to try and learn the new words. Sometimes you have no idea whatsoever what they’re trying to get at. I guessed a lot. But as I proceeded, I was conscious of many “aha” moments, when I finally truly learned what a word meant. That helped. I’m sure this “self-taught” reward system is the lynchpin of the whole Rosetta Stone philosophy.

There are units on grammar, on listening, or speaking, on reading – but they all follow the same general format. The program is clearly geared towards tourism. The units often transparently nodded toward this in their choice of topics.

One problem is that while my confidence in hearing Hebrew and reading went up, my speaking did not. I have a good friend who told me that it’s natural for listening language skills to improve years before speaking skills – so this is normal – but I can’t see how I’ll get better at this without speaking the language with others who can.

One more aside – eight months into this “learning new skills in 2017” project, I’m already starting to see the flaw in my plan. There are only so many hours in the day. This works well for adding in a skill I’d like to have, but rarely use (like drawing), but not for one I’d like to continue (like knitting or meditating). How do I find the time to continue to do the things I enjoyed while learning new things? I need more time.

Anyway, back to this block. the bad news is that I’m nowhere near to fluent. The good news is that I feel like I’ve made a lot of progress, and I’m curious to see if I stick with it, if I’ll get there. I paid for 6 months, and I’m going to try.

tl;dr: Rosetta Stone was a worthwhile investment. But I was an idiot to think I could get this done in two months.

August 30, 2017

Public Health Care Programs: Lower Cost but Not Lower Quality

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2017, The New York Times Company).

In recent days, Democrats have stepped into the health policy vacuum created by the Republicans’ failure to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act. Proposals making the rounds include allowing Americans to buy into Medicare at age 55 or to buy into Medicaid.

Both Medicare and Medicaid pay lower prices to health care providers compared with private market plans offered by employers and in the Affordable Care Act marketplaces. On that basis, you might think these public programs are more cost-efficient. Are they?

Imagine that I take my car to the cheapest mechanic in town, while you take yours to the most expensive. My repairs, though costing less, don’t always fix the problem or last as long. You get what you pay for.

Let’s take a look at whether something similar is happening with public health programs. One study examined claims data for 26 low-value services and found that as much as 2.7 percent of Medicare’s spending is on these services alone, which include ineffective cancer screening, diagnostic testing, imaging and surgery. That sounds pretty bad.

But a paper that appeared in Health Services Research this year suggests that private plans do not perform better. Looking at the years 2009 to 2011, the authors compared the rates at which Medicare and private health plans provided seven low-value services. The services compared were among those identified as unnecessary by national organizations of medical specialists as part of the Choosing Wisely campaign.

The researchers found that four of the seven services they examined were provided at similar rates by Medicare and commercial market plans: cervical cancer screening over age 65; prescription opioid use for migraines; cardiac testing in asymptomatic patients; and frequent bone density scans. Medicare was less likely to pay for unnecessary imaging for back pain, but more likely to pay for vitamin D screening.

This finding might seem counterintuitive. Commercial market plans pay higher rates and confer higher profit margins, meaning there is more financial incentive for physicians to provide privately insured patients more of all types of care, whether low or high value.

But other results from the study suggest a more likely explanation: Doctors tend to treat all their patients similarly, regardless of who is paying the bill.

“What kind of insurance you have does affect your access to health care,” said Carrie Colla, associate professor of the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice and the lead author of the study. “But once you’re in front of the doctor, by and large you’re treated the same way as any other patient.”

One apparent exception found in the study involved the seventh service it examined: cardiac testing before low-risk, noncardiac surgery. This service was provided to 46 percent of Medicare beneficiaries and 26 percent of privately insured patients. The large difference could reflect the fact that cardiac problems are more prevalent among older people. So a doctor with equal concern for all her patients might test Medicare patients at a higher rate for that reason. Nonetheless, such testing is considered low value even for the Medicare population.

Another recent study, published in JAMA Internal Medicine, also found little relationship between insurance status and low-value care. The study found no difference in the rates at which seven of nine low-value services were provided to patients on Medicaid versus those with private coverage. Six were also provided at the same rates for uninsured and privately insured patients.

Moreover, the study found that physicians who see a higher proportion of patients on Medicaid provide the same rate of low- and high-value services for all their patients as other physicians do. This is an important finding because Medicaid pays doctors less than private plans do, raising concerns that higher-quality doctors would tend not to participate in the program.

“Despite concerns to the contrary, Medicaid patients don’t appear to be seeing lower-quality doctors,” said Dr. Michael Barnett, lead author of the study, a physician with the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and an assistant professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “Though raising the prices Medicaid pays doctors may increase physician participation, enhancing enrollees’ access to care, it isn’t likely to change the quality of care patients receive once they are in the doctor’s office.”

If insurance status doesn’t influence how much low-value care patients are being offered, what does? In part, it seems related to the history and organization of local health care markets. A big culprit, according to Ms. Colla’s study, is a market’s ratio of specialists, like cardiologists and orthopedists, to primary care physicians. In areas where there are relatively more specialists, there is also more low-value care. That’s not to say that specialists don’t provide valuable services — but it suggests that they tend to provide more low-value care as well.

In a way, this is good news — the medical system doesn’t seem to discriminate by insurance status. It also means that public programs appear to be relatively cost-efficient, spending less than private payers for care of similar quality. That bodes well for Democrats’ proposals to expand Medicare or Medicaid.

But the bad news is that the study results imply that the value of care is hard to influence by adjusting prices. In a normal market, paying less for something would send a message of its low value, prompting people to provide less of it. The fact that price apparently does not influence doctors’ decisions is just another way in which health care does not seem to function like other markets.

August 29, 2017

Network adequacy standards

This post is jointly authored by Austin Frakt and Yevgeniy Feyman.

Like everything in health care, network adequacy is complicated, with numerous measures and differing regulations by program. This post offers a flavor and a bit of organization of that complexity, based on some of our recent reading.

Medicare Advantage

When is network adequacy assessed? CMS is only certain to assess a plan’s network upon application for a new contract or expansion of a contract’s service area. At its discretion, CMS may review networks at other times, for instance when a plan terminates a contract with a provider, when it changes ownership, or when there are network access complaints or plan-identified network deficiencies.

What types of entities are assessed for adequacy? There are different network adequacy standards for each of 27 practitioner specialty types (e.g., primary care, cardiology, urology) and 23 facility types (e.g., acute inpatient hospitals, outpatient dialysis, mammography).

Are all markets treated equivalently? No. CMS places each county into one of five categories: Large Metro, Metro, Micro, Rural, or CEAC (Counties with Extreme Access Considerations). Within each practitioner and facility type, there are different network adequacy standards by county type. These can change from year-to-year as well.

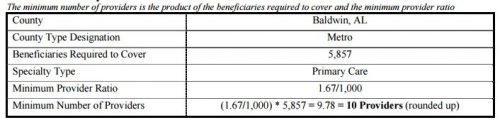

How is network adequacy measured? The gist is that each plan must contract with a specified number of providers of each type. Moreover, 90% of beneficiaries in the county must live within specified travel distance and travel time from at least one provider of each type. To calculate the minimum number of providers, each county receives a population of beneficiaries (termed “beneficiaries required to cover” in the table below) that is equal to the 95th percentile of penetration in all plans in its county type, multiplied by the total number of beneficiaries in the county. That’s a mouthful, but roughly speaking it means that CMS makes sure that each plan can serve a number of beneficiaries larger than it is ever likely to enroll.

This is rather abstract. How about a concrete example? Sure! The following tables should help. The first illustrates the calculation of the number of primary care providers a plan in Baldwin, AL must contract with (10) for 5,857 beneficiaries.

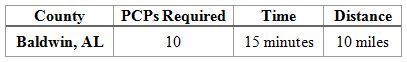

The next table shows that in Baldwin, AL, at least one primary care provider must be within 10 miles and 15 minutes of travel time for 90% of beneficiaries in the county. Additionally, a PCP who is not within the time and distance requirements of at least one beneficiary, will not count towards the minimum number of providers required. Moreover, because at least 90% of beneficiaries must be within the time and distance requirements, a plan may have to contract with more than the minimum number of providers required to meet these requirements.

Where can I learn more? Here are some potentially helpful links:

Most of the foregoing can be found in this CMS guidance document.

Additional details on how time and distance to providers are calculated can be found in this memo.

Here is the most recent file that specifies year-specialty-county type network adequacy regulations.

Marketplaces

The following is for federally facilitated marketplaces, but concludes with a comment about state facilitated ones.

When is network adequacy assessed? As best we can tell, network adequacy is assessed for each plan every year.

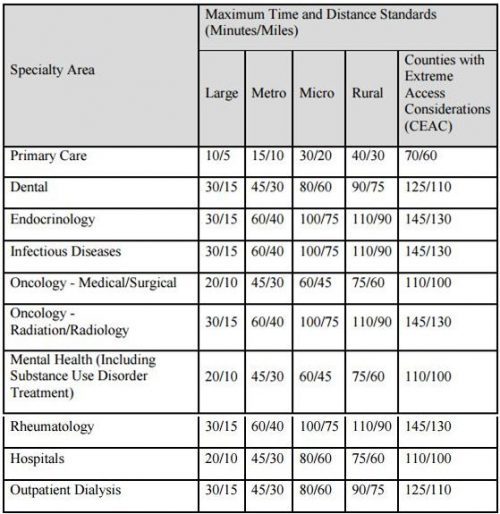

What types of entities are assessed for adequacy? CMS focuses on a subset of specialist areas and facility types that have been associated with network adequacy problems in the past: hospital systems, dental providers (if applicable), endocrinology, infectious disease, mental health, oncology, outpatient dialysis, primary care, and rheumatology. That other specialists and facility types are not necessarily scrutinized is one limitation of the approach.

Are all markets treated equivalently? No. CMS places each county into the same categories used for MA plans’ network adequacy: Large Metro, Metro, Micro, Rural, or CEAC (Counties with Extreme Access Considerations). Within each practitioner and facility type, there are different network adequacy standards by county type. Presumably, these can change from year-to-year as well.

How is network adequacy measured? The approach is similar to that for MA plans: 90% of enrollees must have access to at least one provider/facility type within specified travel distances and travel times. A key difference is that there does not appear to be a minimum number of each provider type every plan must contract with. It’s reasonable to hypothesize, therefore, that marketplace plans would have much more narrow networks than MA plans, but no direct comparison exists, to our knowledge.

This is rather abstract. How about a concrete example? The table below lists the time and distance standards by county and provider type.

Where can I learn more? Here are some potentially helpful links:

Most of the foregoing can be found in this CMS letter to issuers.

Here is a link to the RWJF network adequacy and travel standards dataset

States also have network adequacy statutes and regulations. Historically, most applied to HMOs. Details here and here.

Sex Education Based on Abstinence? There’s a Real Absence of Evidence

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2017, The New York Times Company). I forgot to post it last week.

Sex education has long occupied an ideological fault line in American life. Religious conservatives worry that teaching teenagers about birth controlwill encourage premarital sex. Liberals argue that failing to teach about it ensures more unwanted pregnancies and sexually transmitted diseases. So it was a welcome development when, a few years ago, Congress began to shift funding for sex education to focus on evidence-based outcomes, letting effectiveness determine which programs would get money.

But a recent move by the Trump administration seems set to undo this progress.

Federal support for abstinence-until-marriage programs had increased sharply under the administration of George W. Bush, and focus on it continued at a state and local level after he left office. From 2000 until 2014, the percentage of schools that required education in human sexuality fell to 48 percent from 67 percent. By 2014, half of middle schools and more than three-quarters of high schools were focusing on abstinence. Only a quarter of middle schools and three-fifths of high schools taught about birth control. In 1995, 81 percent of boys and 87 percent of girls reported learning of birth control in school.

Sex education focused on an abstinence-only approach fails in a number of ways.

First, it’s increasingly impractical. Trying to persuade people to remain abstinent until they are married is only getting harder because of social trends. The median age of Americans when they first have sex in the United States is now just under 18 years for women and just over 18 years for men. The median age of first marriage is much higher, at 26.5 years for women and 29.8 for men. This gap has increased significantly over time, and with it the prevalence of premarital sex.

Second, the evidence isn’t there that abstinence-only education affects outcomes. In 2007, a number of studies reviewed the efficacy of sexual education. The first was a systematic review conducted by the National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. It found no good evidence to support the idea that such programs delayed the age of first sexual intercourse or reduced the number of partners an adolescent might have.

The second was a Cochrane meta-analysis that looked at studies of 13 abstinence-only programs together and found that they showed no effect on these factors, or on the use of protection like condoms. A third was published by Mathematica, a nonpartisan research organization, and it, too, found that abstinence programs had no effect on sexual abstinence for youth.

In 2010, Congress created the Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program, with a mandate to fund age-appropriate and evidence-based programs. Communities could apply for funding to put in only approved evidence-based teen pregnancy prevention programs, or evaluate promising and innovative new approaches. The government chose Mathematica to determine independently which programs were evidence-based, and the list is updated with new and evolving data.

Of the many programs some groups promote as being abstinence-based, Mathematica has confirmed four as having evidence of being successful. Healthy Futures and Positive Potential had one study each showing mixed results in reducing sexual activity. Heritage Keepers and Promoting Health Among Teens (PHAT) had one study each showing positive results in reducing sexual activity.

But it’s important to note that there’s no evidence to support that these abstinence-based programs influence other important metrics: the number of sexual partners an adolescent might have, the use of contraceptives, the chance of contracting a sexually transmitted infection or even becoming pregnant. There are many more comprehensive programs (beyond the abstinence-only approach) on the Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program’s list that have been shown to affect these other aspects of sexual health.

Since the program began, the teenage birthrate has dropped more than 40 percent. It’s at a record low in the United States, and it has declined fastersince then than in any other comparable period. Many believe that increased use of effective contraception is the primary reason for this decline; contraception, of course, is not part of abstinence-only education.

There have been further reviews since 2007. In 2012, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention conducted two meta-analyses: one on 23 abstinence programs and the other on 66 comprehensive sexual education programs. The comprehensive programs reduced sexual activity, the number of sex partners, the frequency of unprotected sexual activity, and sexually transmitted infections. They also increased the use of protection (condoms and/or hormonal contraception). The review of abstinence programs showed a reduction only in sexual activity, but the findings were inconsistent and that significance disappeared when you looked at the stronger study designs (randomized controlled trials).

This year, researchers published a systematic review of systematic reviews (there have been so many), summarizing 224 randomized controlled trials. They found that comprehensive sex education improved knowledge, attitudes, behaviors and outcomes. Abstinence-only programs did not.

Considering all this accumulating evidence, it was an unexpected setback when the Trump administration recently canceled funding for 81 projects that are part of the Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program, saying grants would end in June 2018, two years early — a decision made without consulting Congress.

Those 81 projects showed promise and could provide us with more data. It’s likely that all the work spent investigating what is effective and what isn’t will be lost. The money already invested would be wasted as well.

The move is bad news in other ways, too. The program represented a shift in thinking by the federal government, away from an ideological approach and toward an evidence-based one but allowing for a variety of methods — even abstinence-only — to coexist.

The Society of Adolescent Health and Medicine has just released an updated evidence report and position paper on this topic. It argues that many universally accepted documents, as well as international human rights treaties, “provide that all people have the right to ‘seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds,’ including information about their health.” The society argues that access to sexual health information “is a basic human right and is essential to realizing the human right to the highest attainable standard of health.” It says that abstinence-only-until-marriage education is unethical.

Instead of debating over the curriculum of sexual education, we should be looking at the outcomes. What’s important are further decreases in teenage pregnancy and in sexually transmitted infections. We’d also like to see adolescents making more responsible decisions about their sexual health and their sexual behavior.

Abstinence as a goal is more important than abstinence as a teaching point. By the metrics listed above, comprehensive sexual health programs are more effective.

Whether for ethical reasons, for evidence-based reasons or for practical ones, continuing to demand that adolescents be taught solely abstinence-until-marriage seems like an ideologically driven mission that will fail to accomplish its goals.

@aaronecarroll

August 28, 2017

Healthcare Triage: What Kind of Gun Laws Work? Guns and Public Health Part 4

Let’s be honest. The real controversy around the issue of guns is… what might we do about it? It’s the potential policy changes that make people squirrelly. But changes have occurred in the past, we can see what happened, and we can use that to inform what we might do. That’s the topic of this week’s Healthcare Triage.

Some references:

What Do We Know About the Association Between Firearm Legislation and Firearm-Related Injuries?

State background checks for gun purchase and firearm deaths: An exploratory study

Firearm Death Rates and Association with Level of Firearm Purchase Background Check

Effects of the Repeal of Missouri’s Handgun Purchaser Licensing Law on Homicides

Impact of California firearms sales laws and dealer regulations on the illegal diversion of guns

State gun safe storage laws and child mortality due to firearms

Association between youth-focused firearm laws and youth suicides

Firearm-Related Laws in All 50 US States, 1991–2016

State Firearm Law Database

August 23, 2017

Opioid detoxification is not enough

But detoxification is actually extremely dangerous. Nearly every addict who successfully completes a week-long detox program without further treatment relapses, and in a world with increasingly powerful synthetic drugs on the market, the risk of overdosing and dying during a relapse has become ever more threatening.

That’s from a nicely written and brief piece in WaPo by Michael Stein, an internist and the chairman of the department of health law, policy and management at Boston University. Read the whole thing.

A judge rules that EEOC’s rule on wellness programs is busted.

Back in November 2015, I criticized a proposed rule about wellness programs that the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission was then considering. The rule would have allowed employers to impose a financial penalty—up to 30 percent of annual premiums—on employees who declined to participate in a wellness program.

The trouble was that the Americans with Disabilities Act prohibits employers from compelling employees to undergo medical exams, including taking a medical history, unless they’re “voluntary.” And most wellness programs require employees to fill out a health assessment, which is a kind of medical history. As I explained:

[That’s] where the EEOC’s argument falls apart. The average premium for a family plan in 2015 is $17,545; 30% of that is $5,263. Under the EEOC rule, then, an employer can dock an employee with a family more than $5,000 if she doesn’t take a health assessment. With that kind of financial inducement, it’s nuts to say that the assessment is voluntary. Sure, the employee could always turn down the $5,000. But no reasonable person would. The health assessment is mandatory in every meaningful sense of the word.

The EEOC went ahead anyway, saying that it wanted to harmonize its rule with HIPAA, which the ACA had amended in an effort to promote wellness programs. In a subsequent article published in Health Matrix, Adrianna, Aaron, Austin, and I pressed the ADA point again, and identified a handful of other legal problems with the EEOC’s rule, including its inconsistency with the Genetic Information Discrimination Act, or GINA.

The AARP picked up on these arguments and filed suit against the EEOC. Yesterday, the highly respected Judge Bates in Washington, D.C. held that the rule was unlawful for substantially the same reasons that we’d identified:

EEOC does not explain why it makes sense to adopt wholesale the 30% level in HIPAA, which was adopted in a different statute based on different considerations and for different reasons, into the ADA context as a permissible interpretation of the term “voluntary”—a term not included in the relevant provisions of HIPAA—beyond stating that this interpretation “harmonizes” the regulations. …

Significantly, the Court can find nothing in the administrative record—or the final rule—to indicate that the agency considered any factors that are actually relevant to the voluntariness question. Having chosen to define “voluntary” in financial terms—30% of the cost of self-only coverage—the agency does not appear to have considered any factors relevant to the financial and economic impact the rule is likely to have on individuals who will be affected by the rule. … For example, commenters pointed out that, based on the average annual cost of premiums in 2014, a 30% penalty for refusing to provide protected information would double the cost of health insurance for most employees. … At around $1800 a year, this is the equivalent of several months’ worth of food for the average family, two months of child care in most states, and roughly two months’ rent. … Indeed, many of the comments in the administrative record expressed concern that the 30% incentive level was likely to be far more coercive for employees with lower incomes, and was likely to disproportionately affect people with disabilities specifically, who on average have lower incomes than those without disabilities.

The court’s decision leaves open the possibility that EEOC can explain why a 30 percent penalty means that a health assessment is still “voluntary.” But the agency’s failure to do so in the first instance suggests that it will struggle with that assignment—and for good reason. The argument is nuts. (The court also found the EEOC’s rule to be inconsistent with GINA, again for much the same reasons that Adrianna, Aaron, Austin, and I pressed in our article.)

The AARP’s victory may be Pyrrhic, however. In the normal course, a rule that’s found to be arbitrary and capricious would be invalidated. But there’s an exception for rules whose deficiencies are modest and whose invalidation would be disruptive. In those cases, the courts will sometimes keep a rule in place while giving the agency an opportunity to offer a sensible explanation for it.

Judge Bates seemed torn about whether the EEOC’s rule qualified for the exception. The rule’s deficiencies were substantial, he said—but then again, invalidating the rule in the middle of a plan year “appears likely to cause potentially widespread disruption and confusion.” In the end, Judge Bates opted to keep the rule in place to give EEOC a chance fix the rules “in a timely manner.”

I’m a little flummoxed by the remedy. Declining to vacate through the end of 2017 is arguably appropriate; Judge Bates is right that it’d be really disruptive. But EEOC shouldn’t be allowed to keep its rule in effect into 2018 and beyond unless it can offer a reasoned explanation for why a 30 percent penalty isn’t coercive—and I don’t think it can.

Judge Bates’s optimism that EEOC will promptly revisit its rule is likely misplaced. Agencies are notoriously slow to respond when courts decide not to vacate their rules. From their perspective, what’s the rush? The rule remains in place while they dither. Given that, it would have been more appropriate, I think, for Judge Bates to have vacated EEOC’s rule while declining to put his order into effect—in legalese, he should have stayed the release of the mandate—until January 1, 2018.

Staying the mandate would have avoided disruption while still giving EEOC an incentive to quickly revisit its rule. Indeed, I’d strongly encourage the AARP to file a motion to amend the judgment to seek precisely that relief. Given Judge Bates’s “serious concerns about the agency’s reasoning,” he may be receptive to the suggestion.

August 21, 2017

Healthcare Triage: Firearms and Suicide – Guns and Public Health Part 3

We continue our special look at guns and public health in the United States. This week, we’re looking at how easily accessible firearms complicate the suicide rate in the United States. While people have always committed suicide, guns certainly make suicide attempts a lot more likely to succeed. Once again, there are things we can do to mitigate this.

This series was produced with support from the NIHCM Foundation.

Further reading:

Guns and Suicide in the United States

Jumpers

Florida Bill Could Muzzle Doctors On Gun Safety

Hospitalizations Due to Firearm Injuries in Children and Adolescents

The Association Between Presence of Children in the Home and Firearm-Ownership and -Storage Practices

Injuries and deaths due to firearms in the home

Firearm-Related Injuries Affecting the Pediatric Population

Youth Suicide and Access to Guns

Widening Rural-Urban Disparities in Youth Suicides, United States, 1996-2010

The accessibility of firearms and risk for suicide and homicide victimization among household members: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Preventing Teen Suicide: What the Evidence Shows

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2017, The New York Times Company).

Rates of teen suicide continue to rise, federal health officials reported this month, with rates for girls higher than at any point in the last 40 years. A rational response would be to engage in evidence-based measures to try to reverse this course. Too often, we assume that there’s nothing we can do.

Sometimes, we even make things worse.

Suicide rates were even higher in the 1990s. But from 2007 to 2015 rates rose from 10.8 to 14.2 per 100,000 male teenagers and from 2.4 to 5.1 per 100,000 female teenagers. In 2011, for the first time in more than 20 years, more teenagers died from suicide than homicide.

But these trends have been known for years. Our response to them hasn’t adequately acknowledged their progression.

There are evidence-based ways to prevent suicide. The World Health Organization has a guide for how media professionals should talk about the subject. They should avoid sensationalizing it or normalizing it. They should be careful not to repeat accounts of suicide or to provide explicit descriptions as to how suicide might be attempted or completed. They should word headlines carefully, and avoid video or photos of suicides or the victims.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has an evidence-based guide on how to prevent suicide as well. There are things the government can do, including strengthening economic supports, making sure families are more financially secure and have stable housing. The health care system needs to strengthen access to and delivery of mental health care, as well as improve our ability to identify and support teenagers at risk.

There are things we as a society can do as well. We need to make things safer for teenagers, which includes reducing their access to the means they might likely use in a suicide attempt. Also important but more difficult, we need to promote connectedness and limit isolation. The best thing we can do for teens at risk is to prevent them from cutting themselves off from others.

We have been failing to meet these goals too often when it comes to the media, guns and community.

The most public discussion around suicide this year centered on the Netflix series “13 Reasons Why,” adapted from the book of the same title. Supporters of the series argued that the show brought attention to teen suicide, and that it prompted more discussions of the issue — which would be a good thing. Many experts were concerned that the series glamorized suicide, though. They were especially concerned because the producers chose to show the suicide in a long three-minute scene, where the protagonist slit her wrists in a bathtub. In the book, she overdoses on sleeping pills, and it takes place “offscreen.”

Research shows that when the media focuses on the suicide of an entertainment or political celebrity, the copycat effect is much larger. This is even more true when the media focuses on the means by which the suicide occurred. Granted, there’s less of an effect when the suicide is fictional, but even then, it’s associated with more than a quadruple increase in a copycat effect.

Researchers recently published a study that examined the series’s apparent effect on internet searches about suicide. “13 Reasons Why” generated more than 600,000 news reports. In the 19 days after its release, searches about suicide were about 19 percent higher than expected. As hoped, some searches for things like “suicide hotline,” “suicide prevention” and “teen suicide” went up. But so did searches for “commit suicide,” “how to commit suicide” and “how to kill yourself.” The long-term effects of this are unclear, but are certainly concerning enough to monitor.

Our inability to address the issue of guns exacts a cost. There are about twice as many suicides annually using guns (more than 21,000 in 2014) as there are homicides using guns. Almost none of the guns used in suicides are assault weapons, and yet that seems to be the singular focus of many activists. In about 45 percent of suicides among those age 15 to 24, guns were used.

Those who might counter that people who want to kill themselves would find other ways if we limited their access to guns ignore evidence about suicide. Research shows that most suicides are impulsive. Studies of people who came close to dying from suicide attempts, but lived, show that about one-quarter went from deciding to kill themselves to making the attempt in less than five minutes. Almost three-quarters of them took less than an hour.

Having access to guns can make a big difference, because they are devastatingly efficient. Suicide attempts by gun succeed more than 85 percent of the time; attempts by overdose or poisoning succeed less than 2 percent of the time. Meta-analyses show that access to a firearm increases one’s odds of a successful suicide by more than a factor of three.

While we can debate the relative merits of making it easier or harder to own a gun, it’s clear that guns should be kept out of the hands of children.

Finally, we are allowing teenagers to become more withdrawn from others. The Monitoring the Future study has been looking at the behaviors, attitudes and values of American high school students for decades. I pulled data from their archives for 2007 through 2015, specifically looking at high school seniors. In 2007, only 25 percent of them reported going out on dates one or fewer times a month — three-quarters were more social than that. In 2015, the percentage of people reporting one date or fewer in a month had risen to 36 percent. In 2007, the percentage of people who reported going out for fun and recreation one or fewer times per week was 46 percent. By 2015, that had risen to 59 percent.

In an article in The Atlantic, and in a new book, Jean Twenge argues that smartphones and social media have disconnected teenagers from society. Others fear the internet in general also may be doing the same or increasing the potential for bullying without immediate repercussions. I’m not sure we can lay as much of the blame on technology as they do, but all of these data make a strong argument that teenagers are more isolated and at higher risk than before.

We need to talk about suicide in ways that help, not harm. We need to make sure young people have no access to guns. And we need to make sure they are connected enough to each other, to family, and to the health care system so that those at risk can be recognized and given the care they need. The rising toll shows we should not ignore this problem, or pretend that it’s just too hard.

Coverage expansion and primary care access

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2017, The New York Times Company) while I was on vacation.

When you have a health problem, your first stop is probably to your primary care doctor. If you’ve found it harder to see your doctor in recent years, you could be tempted to blame the Affordable Care Act. As the health law sought to solve one problem, access to affordable health insurance, it risked creating another: too few primary care doctors to meet the surge in appointment requests from the newly insured.

Studies published just before the 2014 coverage expansion predicted a demand for millions more annual primary care appointments, requiring thousands of new primary care providers just to keep up. But a more recent study suggests primary care appointment availability may not have suffered as much as expected.

The study, published in April in JAMA Internal Medicine, found that across 10 states, primary care appointment availability for Medicaid enrollees increased since the Affordable Care Act’s coverage expansions went into effect. For privately insured patients, appointment availability held steady. All of the gains in access to care for Medicaid enrollees were concentrated in states that expanded Medicaid coverage. For instance, in Illinois 20 percent more primary care physicians accepted Medicaid after expansion than before it. Gains in Iowa and Pennsylvania were lower, but still substantial: 8 percent and 7 percent.

Though these findings are consistent with other research, including a study of Medicaid expansion in Michigan, they are contrary to intuition. In places where coverage gains were larger — in Medicaid expansion states — primary care appointment availability grew more.

“Given the duration of medical education, it’s not likely that thousands of new primary care practitioners entered the field in a few years to meet surging demand,” said the Penn health economist Daniel Polsky, the lead author on the study. There are other ways doctor’s offices can accommodate more patients, he added.

One way is by booking appointment requests further out, extending waiting times. The study findings bear this out. Waiting times increased for both Medicaid and privately insured patients. For example, the proportion of privately insured patients having to wait at least 30 days for an appointment grew to 10.5 percent from 7.1 percent.

The study assessed appointment availability and wait times, both before the 2014 coverage expansion and in 2016, using so-called secret shoppers. In this approach, people pretending to be patients with different characteristics — in this case with either Medicaid or private coverage — call doctor’s offices seeking appointments.

Improvement in Medicaid enrollees’ ability to obtain appointments may come as a surprise. Of all insurance types, Medicaid is the least likely to be accepted by physicians because it tends to pay the lowest rates. But some provisions of the Affordable Care Act may have enhanced Medicaid enrollees’ ability to obtain primary care.

The law increased Medicaid payments to primary care providers to Medicare levels in 2013 and 2014 with federal funding. Some states extended that enhanced payment level with state funding for subsequent years, but the study found higher rates of doctors’ acceptance of Medicaid even in states that didn’t do so.

The Affordable Care Act also included funding that fueled expansion of federally qualified health centers, which provide health care to patients regardless of ability to pay. Because these centers operate in low-income areas that are more likely to have greater concentrations of Medicaid enrollees, this expansion may have improved their access to care.

Other trends in medical practice might have aided in meeting growing appointment demand. “The practice and organization of medical care has been dynamic in recent years, and that could partly explain our results,” Mr. Polsky said. “For example, if patient panels are better managed by larger organizations, the trend towards consolidation could absorb some of the increased demand.”

Although the exact explanation is uncertain, what is clear is that the primary care system has not been overwhelmed by coverage expansion. Waiting times have gone up, but the ability of Medicaid patients to get appointments has improved, with no degradation in that aspect for privately insured patients.

Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers