Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 124

September 16, 2017

The Economic Case for Letting Teenagers Sleep a Little Later

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2017, The New York Times Company)

Many high-school-aged children across the United States now find themselves waking up much earlier than they’d prefer as they return to school. They set their alarms, and their parents force them out of bed in the morning, convinced that this is a necessary part of youth and good preparation for the rest of their lives.

It’s not. It’s arbitrary, forced on them against their nature, and a poor economic decision as well.

The National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute recommends that teenagers get between nine and 10 hours of sleep. Most in the United States don’t. It’s not their fault.

My oldest child, Jacob, is in 10th grade. He plays on the junior varsity tennis team, but his life isn’t consumed by too many extracurricular activities. He’s a hard worker, and he spends a fair amount of time each evening doing homework. I think most nights he’s probably asleep by 10 or 10:30.

His school bus picks him up at 6:40 a.m. To catch it, he needs to wake up not long after 6. Nine hours of sleep is a pipe dream, let alone 10.

There’s an argument to be made that we should cut back on his activities or make him go to bed earlier so that he gets more sleep. Teens aren’t wired for that, though. They want to go to bed later and sleep later. It’s not the activities that prevent them from getting enough sleep — it’s the school start times that require them to wake up so early. More than 90 percent of high schools and more than 80 percent of middle schools start before 8:30 a.m.

Some argue that delaying school start times would just cause teenagers to stay up later. Research doesn’t support that idea. A systematic review published a year ago examined how school start delays affect students’ sleep and other outcomes. Six studies, two of which were randomized controlled trials, showed that delaying the start of school from 25 to 60 minutes corresponded with increased sleep time of 25 to 77 minutes per week night. In other words, when students were allowed to sleep later in the morning, they still went to bed at the same time, and got more sleep.

There are costs to pushing back the start times of schools, of course. Our local school system, like many others, uses the same buses for elementary, middle and high school. Not wanting to start elementary school too early, it starts high school earlier to save money on transportation. Other costs to delaying start times come after school, when later school end times result in later after-school activities. These can interfere with parents’ work schedules and run into evening hours, when it gets dark and additional lighting might be necessary.

A Brookings Institution policy brief investigated the trade-offs between costs and benefits of pushing back the start times of high school in 2011. It estimated that increased transportation costs would most likely be about $150 per student per year. But more sleep has been shown to lead to higher academic achievement. They found that the added academic benefit of later start times would be equivalent to about two additional months of schooling, which they calculated would add about $17,500 to a student’s earnings over the course of a lifetime. Thus, the benefits outweighed the costs.

This was a reasonably simple analysis, though, and did not persuade many schools to change. A recent analysis by the RAND Corporation goes much further.

Marco Hafner, Martin Stepanek and Wendy Troxel conducted analyses to determine the economic implication of a universal shift of middle and high school start times to 8:30 a.m. at the earliest. This study was stronger than the Brookings one in a number of ways. It examined each state individually, because moving to 8:30 would be a bigger change for some than for others. It also looked at changes year by year to see how costs and benefits accrued over time. It examined downstream effects, like car accidents, which can affect lifetime productivity. And it considered multiplier effects, as changes to the lives of individual students might affect others over time.

They found that delaying school start times to 8:30 or later would contribute $83 billion to the economy within a decade. The gains were seen through decreased car crash mortality and increased student lifetime earnings.

Since it would take at least a year for any students affected by changes in start times to enter the labor market, there would be no gains in the first year. Costs, however, would accrue immediately. These included about $150 per student per year in transportation costs and $110,000 per school costs in upfront infrastructure upgrades. Even so, by the second year, the benefits outweighed the costs. By 10 years, the benefits were almost double the costs; by 15 years, they were almost triple.

We’d be remiss if we didn’t acknowledge other potential costs not included in this calculation, including parental difficulty in adapting to later school start times. But even in a model where the per-student, per-year cost was increased to $500, which would compensate most parents for delays, and where the upfront per school cost was increased to $330,000, the economic benefits to society would still outweigh the costs in the long run.

Further, it’s important to understand that these benefits may actually be underestimates. The researchers were careful to model only outcomes for which they had empirical data from sleep duration, such as car crashes and academic performance. They didn’t model other real, but quantifiably unknown, benefits, like improvements in rates of depression, suicide and obesity, or the overall effects on health.

Some schools are beginning to take this seriously, but not enough. When it comes to start times, the growing evidence shows that forcing adolescents to get up so early isn’t just a bad health decision; it’s a bad economic one, too.

September 14, 2017

Healthcare Triage News: Senate Republicans Longshot Repeal and Replace Bill

Senate Republicans are going to give it one more try on repealing and replacing Obamacare. This week, Senators Bill Cassidy (LA) and Lindsey Graham (SC) plan to bring forward a bill to repeal and replace the Afffordable Care Act. It’s got a lot of hurdles to clear. We’ve got the details (such as they are).

Can the courts stop 1332 waivers from taking effect?

Iowa has submitted a waiver proposal under section 1332 of the Affordable Care Act that, if granted, would radically reshape its individual insurance market; Oklahoma may soon do the same. Both states have been accused of relying on some magical numbers, and Iowa’s waiver appears to violate the ACA’s guardrails, which require states to assure that any new approach covers at least as many people with coverage that’s at least as comprehensive and affordable.

But what happens if HHS approves the waivers anyhow? Could the courts block them from taking effect?

You bet. Although neither of the two waivers that have been granted so far (Hawaii’s and Alaska’s) has attracted a court challenge, we’ve had decades of experience with challenges to waivers granted under section 1115 of the Social Security Act. Most of those challenges have failed, but back in 1994, in Beno v. Shalala, the Ninth Circuit ruled in favor of a group of welfare beneficiaries who challenged the grant of a California waiver.

Invoking the presumption in favor of judicial review of agency action, the court rejected HHS’s argument that the courts couldn’t review its decision to grant a waiver. “The statute does not give the Secretary unlimited discretion. It allows waivers only for the period and extent necessary to implement experimental projects which are ‘likely to assist in promoting the objectives’ of the [welfare] program.”

With that in mind, the court enjoined California’s waiver from taking effect. In the court’s view, HHS never explained how the waiver—which would have imposed work requirements on welfare recipients—was a genuine experiment or would advance the program’s objectives. In 2011, the Ninth Circuit issued a similar ruling when Arizona sought to impose copayments on Medicaid beneficiaries.

Courts in other circuits have universally agreed that the decision to grant an 1115 waiver can be challenged in court. Their reasoning should apply with equal force to 1332 waivers. (Although the ACA precludes the courts from reviewing some agency decisions, there’s no preclusion language for 1332 waivers.) All you have to do is find a litigant who can plausibly allege that the waiver will make her life worse. For waivers like Iowa’s, that won’t be remotely difficult.

Still, the courts tend to be very deferential to HHS. They’re not really equipped to second-guess the agency’s predictive judgments about a waiver’s on-the-ground consequences, as Judge Friendly explained more than 30 years ago. But deference only goes so far. For 1332 waivers, the courts will still ask hard questions about whether the waiver in question adheres to the guardrails.

That’s going to be a problem for waivers like Iowa’s, which would divert funding for cost-sharing reductions and eliminate protections against excessive out-of-pocket spending. As David Anderson notes:

The Iowa waiver submission will increase the number of low income residents with high percentages of their income devoted to health care costs. The hypothetical 40 year old who has an expensive chronic condition will see a dramatic change in his total out of pocket spending from 8.52% of income under the ACA to 44% of income … . There will be a number of individuals who will have significant, real and obvious harms from this waiver. I will be shocked if at least one of them does not file suit to stop the Iowa waiver for at least the 2018 plan year.

I’ll be shocked, too. How on earth does Iowa’s waiver provide “cost sharing protections against excessive out-of-pocket spending that are at least as affordable” as the ACA, as the statute requires? It eliminates those protections!

Deferential or not, the courts won’t stand for this. The guardrails are really restrictive. If you take them seriously—and the courts will, even if HHS doesn’t—they suggest that a state’s waiver can be approved if and only if it doesn’t make a substantial number of people worse off than they were under the ACA. Iowa’s waiver flunks that test.

Iowa is nonetheless pressing forward—and on an expedited, emergency basis so that its waiver can take effect for 2018. If the waiver is approved, however, there’s a very good chance a court will enter a preliminary injunction to prevent it from taking effect. That’s the worst of all worlds for Iowa. Inviting a legal battle on the eve of open enrollment will not give insurers the confidence they need to participate on the exchanges.

What’s true in Iowa is true for other red states. If they want to revamp their insurance markets, they’re going to have to ask Congress to relax the guardrails. Maybe Congress will oblige, either in Cassidy-Graham or in a bipartisan deal to include more targeted fixes. In the meantime, the courts probably won’t allow the states to radically change the ACA’s structure through waivers.

Blaming Medicaid for the Opioid Crisis: How the Easy Answer Can Be Wrong

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2017, The New York Times Company) and was jointly authored by Aaron Carroll and Austin Frakt.

The theory has gained such prominence that a United States senator is investigating it.

“Medicaid expansion may be fueling the opioid epidemic in communities across the country,” Senator Ron Johnson, Republican of Wisconsin, wrote recently.

Some conservative opponents of the Affordable Care Act have been passing around the same theory for months. It’s a politically explosive (and convenient) argument, but is it true? Substantial evidence suggests the answer is no, but let’s give it a fair hearing.

Some data seems to support this connection, and the idea has a certain logic. Coverage from Medicaid — or any kind of health insurance for that matter — plays a role in access to prescription opioids, just as it does for access to many other types of health care.

We know from earlier analyses that Medicaid enrollees tend to be prescribed opioids more frequently than people with other kinds of coverage. But that could be because of other factors also related to insurance. It’s important to remember that people who go on Medicaid are sicker than those with other forms of coverage, so they may have more pain that warrants opioids.

It is also true that the 31 states that expanded Medicaid experienced a larger increase in drug overdoses between 2013 and 2015 than states that did not. As Mr. Johnson wrote, “These data appear to point to a larger problem.”

But this is a weak foundation on which to base a conclusion that Medicaid is driving the opioid epidemic. Responding to these facts when they were first noted, a Department of Health and Human Services statement said, “Correlation does not necessarily prove causation, and additional research is required before any conclusions can be made.”

In a post on the Health Affairs blog, Andrew Goodman-Bacon, an economist at Vanderbilt, and Emma Sandoe, a Ph.D. student in health policy and political analysis at Harvard, recommend that, to understand the opioid epidemic and Medicaid’s role better, we should look much further back than 2013.

For example, OxyContin prescriptions for noncancer pain grew by a factor of almost 10 between 1997 and 2002, long before the A.C.A. was signed into law. Drug-related mortality rates doubled between 1999 and 2013, the year before most states expanded Medicaid.

Further, while it is true that drug-related deaths have grown more rapidly in expansion states than in other states, that more rapid growth started in 2010, before the A.C.A. expansion. This suggests that causes other than Medicaid are more likely. Given the timing of these findings, “there is little evidence to support the claim that Medicaid expansion caused the increase in opioid-related deaths,” Ms. Sandoe said.

Yes, Medicaid could still be playing a role, but as with all correlations, it’s important to consider both directions of causality. It’s possible that states experiencing larger growth in drug deaths might have been more eager to expand Medicaid programs. After all, Medicaid also provides financial support for drug abuse treatment. One study found that prescriptions for medications that treat opioid addiction increased by 43 percent in Medicaid expansion states, relative to states that did not expand their programs. When Gov. John Kasich, a Republican, talks about why he’s happy that Ohio expanded the Medicaid program, he often cites the opioid crisis in his state.

Craig Garthwaite, a Republican labor economist of Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management, said: “It’s not that there isn’t a single case of an individual insured by Medicaid developing an opioid habit or illicitly obtaining drugs. But the evidence to date doesn’t suggest that this is the net effect.”

Another way to test the Medicaid-opioid connection is to examine a dose response. States with higher levels of uninsurance saw greater coverage gains through Medicaid. If more Medicaid causes more opioid death, then states that added more Medicaid beneficiaries should see greater increases than states with smaller coverage expansions. But Mr. Goodman-Bacon and Ms. Sandoe show that the opposite holds. Counties in states with historically higher levels of uninsurance (and therefore greater subsequent growth in Medicaid) had lower growth in drug-related death rates from 2010 to 2015. This relationship holds within expansion and nonexpansion states separately.

Or course, drug-related deaths include those from prescription opioids as well as those from black-market drugs (like heroin and fentanyl). Medicaid directly enhances access only to the former. This makes it hard to identify the role of Medicaid in the opioid crisis definitively, which is all the more reason to be cautious about suggesting the program is fueling it.

“The really sad thing here is that these numerical arguments have the veneer of seriousness, and as a result, they can drive really bad policy,” Mr. Garthwaite said.

Providing health care through insurance means providing access to both its benefits and harms. No one seems concerned that the increased access to health care that private insurance provides might lead more people to take opioids — only that Medicaid could. It’s also interesting to note that no one makes assertions that increased coverage, even increased Medicaid coverage, probably leads to more deaths by medical errors.

We should not look at harms in isolation. Even if Medicaid does enhance access to prescription opioids, thereby playing a role in their misuse, that is far from the only thing the program does. Medicaid provides many other benefits, about which we’ve written, including increased access to substance use disorder treatment.

To use a theoretical Medicaid-opioid connection (for which the evidence is weak anyway) to justify scaling back Medicaid ignores the larger picture — that it is a crucial aspect of our safety net, providing access to health care and financial protection that many low-income Americans could not otherwise obtain.

September 13, 2017

The Medicare for All Act is more than just universal coverage

Senator Sanders has released the text of his Medicare for All Act. This bill won’t be enacted in this Congress, so the point of introducing it now is to stimulate discussion, above all about the principles that should guide the design of the American health care system. Most of the discussion so far has focused on universal coverage, and the bill delivers that:

Every individual who is a resident of the United States is entitled to benefits for health care services under this Act.

But there’s a lot more than just universal coverage in Senator Sanders’ bill and I want to quickly highlight some of those features.

Comprehensive benefits. The Act requires the provision of hospital, ambulatory care, preventive care, and prescription drugs. It also covers several important domains of health care that have not been adequately supported: oral health (that is, dentistry), mental health, substance abuse, and

comprehensive reproductive, maternity, and newborn care.

In any reasonable construal of comprehensive reproductive care, this would require providers to supply contraceptive care. This will be controversial, to say the least. Because it includes mental health, substance abuse care, and dentistry, this list is notably better than covered services required by the Canada Health Act.

Non-discrimination. By design, the Act eliminates discrimination on the basis of pre-existing conditions. But it also bans discrimination

on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, or sex, including sex stereotyping, gender identity, sexual orientation, and pregnancy and related medical conditions (including termination of pregnancy) [emphasis added]

Working out what the italicized words require will be, let’s say, interesting.

Health disparities. The Act identifies health disparities associated with

race, ethnicity, gender, geography, or socioeconomic status

as a quality of care problem. The mention of geography is particularly interesting, in that accessibility problems associated with living in rural or remote areas are an underappreciated dimension of health disparities.

Evidence-based policymaking. The Act requires HHS to

develop methodological standards for evidence-based policymaking.

This brief phrase tells us nothing about the scope of such standards, what criteria would be used to develop them, or how evidence should constrain policy-making. Nevertheless, if we could do this right…!

National reporting. Currently, Medicare is too much about just cutting checks and policing fraud. Medicare for All would have a mandate to improve system performance on

outcomes, costs, quality, and equity.

The inclusion of equity in this list is important and — please correct me — a first. At the same time, the Act would require providers to supply data while balancing this with a goal to minimize

the administrative burdens of data collection and reporting on providers.

These goals are in tension, but that doesn’t mean that the Act is incoherent. They are in tension because that is how the world is. The legislation also includes whistleblower protections for providers who report problems in billing and quality.

Negotiation of prices. The government would be able to negotiate prices on prescription drugs, medical devices, and equipment (and, please God, let this allow the government to negotiate prices for information technology).

Destruction of Employer-Sponsored Insurance. As Aaron has described,

The single largest tax expenditure in the United States is for employer-based health insurance.

The expenditure is wasteful and highly regressive. The Act bans employer-sponsored benefits that duplicate the comprehensive benefits offered by Medicare for All.

Automatic enrollment. The plan to automatically enroll people into Medicare for All might seem like a detail. However, many Americans cannot exercise rights or access entitlements because they have difficulty completing burdensome enrollment procedures.

No-balance billing. The Medicare for All Act bans co-pays. This will generate much discussion. But note that the Act also states that

no provider may impose a charge to an enrolled individual for covered services for which benefits are provided under this Act.

This would, among other benefits, eliminate surprise billing.

Increased coverage of long-term care. I study kids and long-term care is beyond my remit. But I read this act as seeking to increase Medicare’s coverage of long-term care.

When I wrote about the Canada Health Act, I noted that we have many significant gaps between the principles in the Act and its implementation. In that light, there are many points in the Medicare for All Act which require further clarification. There is also a list of points that worry me.

Nevertheless, if the Medicare for All were passed and successfully implemented, it would have far reaching effects on US health care beyond universal coverage.

DISCLOSURE: I provided Senator Sanders’ staff with comments and suggested language in the drafting of the bill.

September 7, 2017

If you have anything bad to say about kids today, just shut up

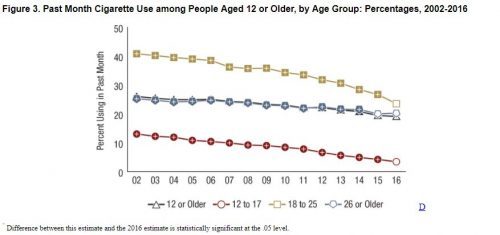

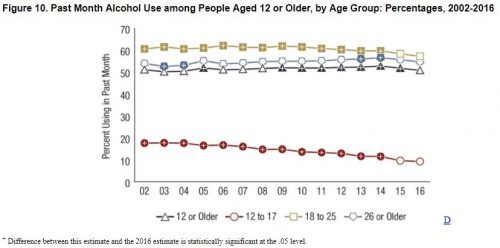

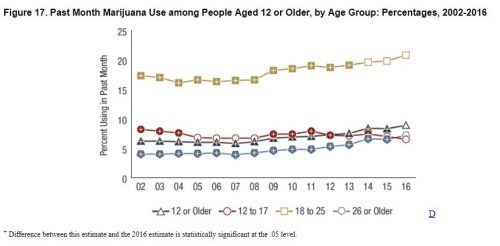

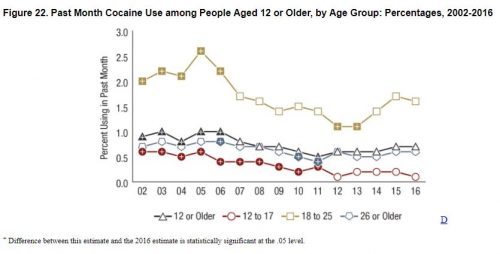

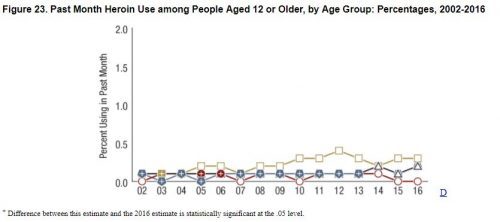

I guess you could find something wrong with some kid, somewhere, but come on. Data are from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. In each of these charts, kids 12-17 are the RED LINE.

Cigarette use:

Alcohol use:

Pot use. And this is after legalization, when lots of you started screaming that this would HAVE to lead to increased use:

Cocaine:

Heroin:

Things don’t look good for all age groups, but for adolescents – the red line – we’re pretty much at the lows. Not to mention teen pregnancy rates and teen births continue their all time lows. What more do you want from them?

Healthcare Triage News: Congress is Back, and Healthcare Should Be on the To-do List

Congress is back in session, and it has a full month ahead. They have to deal with hurricanes, raise the debt limit, fund the government, keep us out of war, AND they want to talk about cutting taxes, too. With all this going on, it’s going to be hard to get anything done around healthcare, but there’s lots that needs to be done.

The Real Reason the U.S. Has Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2017, The New York Times Company).

The basic structure of the American health care system, in which most people have private insurance through their jobs, might seem historically inevitable, consistent with the capitalistic, individualist ethos of the nation.

In truth, it was hardly preordained. In fact, the system is largely a result of one event, World War II, and the wage freezes and tax policy that emerged because of it. Unfortunately, what made sense then may not make as much right now.

Well into the 20th century, there just wasn’t much need for health insurance. There wasn’t much health care to buy. But as doctors and hospitals learned how to do more, there was real money to be made. In 1929, a bunch of hospitals in Texas joined up and formed an insurance plan called Blue Cross to help people buy their services. Doctors didn’t like the idea of hospitals being in charge, so some in California created their own plan in 1939, which they called Blue Shield. As the plans spread, many would purchase Blue Cross for hospital services, and Blue Shield for physician services, until they merged to form Blue Cross and Blue Shield in 1982.

Most insurance in the first half of the 20th century was bought privately, but few people wanted it. Things changed during World War II.

In 1942, with so many eligible workers diverted to military service, the nation was facing a severe labor shortage. Economists feared that businesses would keep raising salaries to compete for workers, and that inflation would spiral out of control as the country came out of the Depression. To prevent this, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9250, establishing the Office of Economic Stabilization.

This froze wages. Businesses were not allowed to raise pay to attract workers.

Businesses were smart, though, and instead they began to use benefits to compete. Specifically, to offer more, and more generous, health care insurance.

Then, in 1943, the Internal Revenue Service decided that employer-based health insurance should be exempt from taxation. This made it cheaper to get health insurance through a job than by other means.

After World War II, Europe was devastated. As countries began to regroup and decide how they might provide health care to their citizens, often government was the only entity capable of doing so, with businesses and economies in ruin. The United States was in a completely different situation. Its economy was booming, and industry was more than happy to provide health care.

This didn’t stop President Truman from considering and promoting a national health care system in 1945. This idea had a fair amount of public support, but business, in the form of the Chamber of Commerce, opposed it. So did the American Hospital Association and American Medical Association. Even many unions did, having spent so much political capital fighting for insurance benefits for their members. Confronted by such opposition from all sides, national health insurance failed — for not the first or last time.

In 1940, about 9 percent of Americans had some form of health insurance. By 1950, more than 50 percent did. By 1960, more than two-thirds did.

One effect of this system is job lock. People become dependent on their employment for their health insurance, and they are loath to leave their jobs, even when doing so might make their lives better. They are afraid that market exchange coverage might not be as good as what they have (and they’re most likely right). They’re afraid if they retire, Medicare won’t be as good (they’re right, too). They’re afraid that if the Affordable Care Act is repealed, they might not be able to find affordable insurance at all.

This system is expensive. The single largest tax expenditure in the United States is for employer-based health insurance. It’s even more than the mortgage interest deduction. In 2017, this exclusion cost the federal government about $260 billion in lost income and payroll taxes. This is significantly more than the cost of the Affordable Care Act each year.

This system is regressive. The tax break for employer-sponsored health insurance is worth more to people making a lot of money than people making little. Let’s take a hypothetical married pediatrician with a couple of children living in Indiana who makes $125,000 (which is below average). Let’s also assume his family insurance plan costs $15,000 (which is below average as well).

The tax break the family would get for insurance is worth over $6,200. That’s far more than a similar-earning family would get in terms of a subsidy on the exchanges. The tax break alone could fund about two people on Medicaid. Moreover, the more one makes, the more one saves at the expense of more spending by the government. The less one makes, the less of a benefit one receives.

The system also induces people to spend more money on health insurance than other things, most likely increasing overall health care spending. This includes less employer spending on wages, and as health insurance premiums have increased sharply in the last 15 years or so, wages have been rather flat. Many economists believe that employer-sponsored health insurance is hurting Americans’ paychecks.

There are other countries with private insurance systems, but none that rely so heavily on employer-sponsored insurance. There are almost no economists I can think of who wouldn’t favor decoupling insurance from employment. There are any number of ways to do so. One, beloved by wonks, was a bipartisan plan proposed by Senators Ron Wyden, a Democrat, and Robert Bennett, a Republican, in 2007. Known as the Healthy Americans Act, it would have transitioned everyone from employer-sponsored health insurance to insurance exchanges modeled on the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program.

Employers would not have provided insurance. They would have collected taxes from employees and passed these onto the government to pay for plans. Everyone, regardless of employment, would have qualified for standard deductions to help pay for insurance. Employers would have been required to increases wages over two years equal to what had been shunted into insurance. Those at the low end of the socio-economic spectrum would have qualified for further premium help.

This isn’t too different from the insurance exchanges we see now, writ large, for everyone. One can imagine that such a program could have also eventually replaced Medicaid and Medicare.

There was a time when such a plan, being universal, would have pleased progressives. Because it could potentially phase out government programs like Medicaid and Medicare, it would have pleased conservatives. When first introduced in 2007, it had the sponsorship of nine Republican senators, seven Democrats and one independent. Such bipartisan efforts seem a thing of the past.

We could also shift away from an employer-sponsored system by allowing people to buy into our single-payer system, Medicare. That comes with its own problems, as The Upshot’s Margot Sanger-Katz has written. She also has covered the issues of shifting to a single-payer system more quickly.

It’s important to point out that neither of these options has anything even close to bipartisan support.

Without much pressure for change, it’s likely the American employer-based system is here to stay. Even the Affordable Care Act did its best not to disrupt that market. While the system is far from ideal, Americans seem to prefer the devil they know to pretty much anything else.

September 5, 2017

The Long-Term Health Consequences of Hurricane Harvey

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2017, The New York Times Company) and is jointly authored by Aaron Carroll and Austin Frakt.

Long after the floodwaters recede, and even during cleanup and rebuilding, the people who lived through Hurricane Harvey will face another form of recovery — from the storm’s blows to physical and mental health.

The short-term health effects of floods capture our attention. Harvey has already caused dozens of deaths, and in 2005 Hurricane Katrinakilled more than 1,800 people.

Yet people endure injuries and illnesses in numbers that far exceed the death toll. When Hurricane Iniki hit Hawaii in 1992, injuries went up by a factor of six, and more than half those injuries were open wounds. Waterborne and communicable respiratory and gastrointestinal disease can spread amid the breakdown in water sanitation, contamination from industrial or hazardous waste sites, or the higher density of people crowding into shelters.

A systematic review published just months ago showed how various phases of flooding and storm disasters affect health. Researchers found that wounds, poisonings and infections of the gut and skin increase soon after storms. Gastrointestinal infections increase more frequently after floods. Diabetes-related complications increase after both.

People with chronic conditions like cardiovascular disease or respiratory illness are particularly prone to health problems immediately after a storm, and their care can be complicated by lack of necessary medications or access to medical records. After Hurricane Katrina, one study found that 14 percent of emergency visits to health care facilities were to treat chronic conditions, and almost 30 percent of those seeking care were sick enough to warrant admission, which is much higher than average for emergency departments. An additional 7 percent of emergency visits were to fill medications.

Visits to the doctor for conditions such as asthma and heart disease also increased significantly after Hurricane Iniki. Harvey caused the shutdown of dozens of dialysis centers. Patients with kidney disease rely on dialysis several times per week, and missing even one session can have severe consequences.

But large floods and other natural disasters have longer-term physical and mental health consequences we’re less attuned to. Well after the event has faded as a top news story, victims continue to suffer and struggle.

A 2012 systematic review published in Environment International documented floods’ tolls on human health, also covering longer-term effects. Flood-affected areas can experience higher mortality rates for months. For example, after Hurricane Katrina, the mortality rate in the New Orleans area was 47 percent above normal for the first half of 2006, up to 10 months after the storm. After Iniki, the mortality ratefrom diabetes went up significantly in the year after. Heightened rates of chronic illnesses can persist in flooded areas for decades.

Many studies document a surge in mental health diagnoses in populations that experience floods. These, too, can last years. Six months after floods in Mexico in 1999, a quarter of the affected population still had symptoms of trauma or depression. Increased rates of both could still be detected two years later, particularly among those among those who had experienced the worst aspects of flooding: flash floods, mudslides, the witnessing of injury or death, and displacement.

Similarly, months after floods in Thailand and South Korea, those with more harrowing experiences were four times more likely to have symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder or depression.

In a post-Katrina assessment, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that though a quarter of respondents lived with someone who needed mental health counseling, fewer than 2 percent received it. Another C.D.C. assessment found that one-fifth to one-quarter of New Orleans police officers had symptoms of P.T.S.D. or depression three months after the flood. Other analyses showed that suicide rates spiked in New Orleans in this period and that rates of P.T.S.D. among workers there were high.

Floods can also have lasting effects on infants and children. With access to obstetric services challenged during and after a flood — as well as negative effects on pregnant women’s physical and mental health — researchers have found worse pregnancy outcomes in flooded areas. One study of women who became pregnant in the six months after Hurricane Katrina found that exposure to the hurricane was associated with earlier delivery and delivery of a lower-weight infant. Another study of pregnant women exposed to flooding in North Dakota in 1997 had similar findings, but also found increased risks to the mother, including anemia, eclampsia and uterine bleeding.

Research tells us how we might respond to natural disasters like Harvey. Recommendations include public education about health effects and precautions, and improved surveillance programs to detect diseases or complications that usually increase after a disaster. They also include monitoring communities for mental health problems, then providing the services needed to care for them, and paying special attention to pregnant women. If you or those you know have been directly affected by Harvey, the C.D.C. has many helpful links on how to cope with a disaster or traumatic event.

Everyone is understandably focused on the immediate dangers from flooding. But analysis of previous natural disasters shows that Harvey’s survivors will need attention and care far into the future.

September 2, 2017

Advertising cutbacks reduce Marketplace information-seeking behavior: Lessons from Kentucky for 2018

This is a guest blog post authored by Paul Shafer, MA; Erika Franklin Fowler, PhD; Laura Baum, MURP; and Sarah Gollust, PhD. Paul Shafer is a PhD student at the University of North Carolina and a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health Policy Research Scholar. Erika Franklin Fowler is Associate Professor of Government at Wesleyan University and co-director of the Wesleyan Media Project. Laura Baum is the project manager for the Wesleyan Media Project. Sarah Gollust is an associate professor in the Division of Health Policy and Management at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health and the associate director of RWJF’s Interdisciplinary Research Leaders program. You can follow the authors on Twitter at @shaferpr, @efranklinfowler, @wesmediaproject, and @sarahgollust.

The Trump administration announced Thursday that it was cutting spending on advertising for the 2018 Marketplace open enrollment period from $100 to $10 million. Empirical work can inform our expectations for its impact, assuming these cuts are implemented. We already know that higher exposure to advertising has been associated with perceptions of feeling more informed about the ACA and counties with more television advertising saw larger decreases in the uninsured rate during the 2014 open enrollment period.

Kentucky— an early success story under the ACA—sponsored a robust multimedia campaign to create awareness about its state-based marketplace, known as kynect, to educate its residents about the opportunity to gain coverage. However, after the 2015 gubernatorial election, the Bevin administration declined to renew the advertising contract for kynect and directed all pending advertisements to be canceled with approximately six weeks remaining in the 2016 open enrollment period. The reduction in advertising during open enrollment gives us precisely the rare leverage needed to assess the influence of advertising using real-world data.

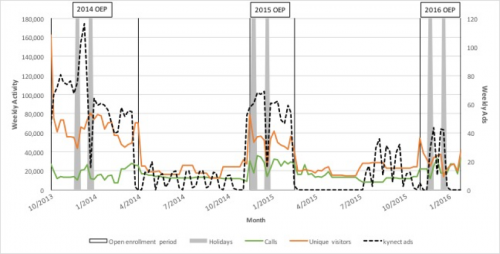

We obtained advertising and Marketplace data in Kentucky to identify whether a dose-response relationship exists between weekly advertising volume and information-seeking behavior. Television advertising data for Kentucky were obtained from Kantar Media/CMAG through the Wesleyan Media Project. These data provide tracking of individual ad airings, including date, time, sponsor, station, and media market. We used a population-weighted average to create a state-level count of kynect ads shown per week. Our outcome measures were related to information-seeking behavior—phone calls to the marketplace and metrics related to engagement on the kynect website—and came from the Office of the Kentucky Health Benefit Exchange via public records request. We used multivariable linear regression models to identify variation in each outcome attributable to kynect advertising and estimated marginal effects to identify the influence of advertising during open enrollment.

FIGURE 1: Weekly advertising and information-seeking behavior in Kentucky, Oct. 1, 2013–Jan. 31, 2016

† OEP=open enrollment period, Holidays=weeks of Thanksgiving and Christmas

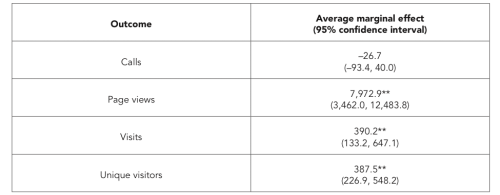

State-sponsored advertising for kynect fell from an average of 58.8 and 52.3 ads per week during the 2014 and 2015 open enrollment periods to 19.4 during the first nine weeks of the 2016 open enrollment period and none during the final four weeks. We found that advertising volume was strongly associated with information-seeking behavior through the kynect web site (see Figure 1). Each additional kynect ad per week during open enrollment was associated with an additional 7,973 page views (P=.001), 390 visits (P=.003), and 388 unique visitors (Pper week during open enrollment without the television campaign. Advertising volume during open enrollment was not associated with calls to the kynect call center.

TABLE 1. Multivariable linear regression models for kynect advertising on weekly information-seeking behavior in Kentucky, Oct. 1, 2013–Jan. 31, 2016

* PP

† Models also control for weekly advertising volume for other five sponsor types (healthcare.gov, insurers, insurance agencies, nonprofits, other state governments), their interaction with the open enrollment indicator, and number of days in the reporting period.

Our analysis tells us that state-sponsored television advertising was a substantial driver of information-seeking behavior in Kentucky during open enrollment––a critical step to getting consumers to shop for plans, understand their eligibility for premium tax credits or Medicaid, and enroll in coverage. Extrapolating to the national landscape, our data suggest that lower expenditures on outreach and advertising would reduce consumers’ information seeking. The announced 90% reduction will be paired with a nearly 40% cut to in-person enrollment assistance through navigator programs. This is particularly problematic after a tumultuous summer of legislative threats to the ACA, possibly leaving consumers confused about whether Obamacare is still the law of the land. Lower outreach could lead to a failure to engage so-called healthy procrastinators, resulting in weaker enrollment and a worsening risk pool for insurers. With an already shortened open enrollment period, this cascade of cuts is likely to further jeopardize the stability of the Marketplace.

Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers