Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 120

October 25, 2017

The Cookie Crumbles: A Retracted Study Points to a Larger Truth

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2017, The New York Times Company).

Changing your diet is hard. So is helping our children make healthy choices. When a solution comes along that seems simple and gets everyone to eat better, we all want to believe it works.

That’s one reason a study by Cornell researchers got a lot of attention in 2012. It reported that you could induce more 8-to-11-year-olds to choose an apple over cookies if you just put a sticker of a popular character on it. That and similar work helped burnish the career of the lead author, Brian Wansink, director of the Cornell Food and Brand Lab.

Unfortunately, we now know the 2012 study actually underscores a maxim: Nutrition research is rarely simple.

Last week the study, which was published in a prestigious medical journal, JAMA Pediatrics, was formally retracted, and doubts have been cast about other papers involving Mr. Wansink.

When first published, the study seemed like an enticing example of behavioral economics, nudging children to make better choices.

Before the study period, about 20 percent of the children chose an apple, and 80 percent the cookie. But when researchers put an Elmo sticker on the apple, more than a third chose it. That’s a significant result, and from a cheap, easily replicated intervention.

While the intervention seems simple, any study like this is anything but. For many reasons, doing research in nutrition is very, very hard.

First, the researchers have to fund their work, which can take years. Then the work has to be vetted and approved by an Institutional Review Board, which safeguards subjects from potential harm. I.R.B.s are especially vigilant when studies involve children, a vulnerable group. Even if the research is of minimal risk, this process can take months.

Then there’s getting permission from schools to do the work. As you can imagine, many are resistant to allowing research on their premises. Often, protocols and rules require getting permission from parents to allow their children to be part of studies. If parents (understandably) refuse, figuring out how to do the work without involving some children can be tricky.

Finally, many methodological decisions come into play. Let’s imagine that we want to do a simple test of cookies versus apples, plus or minus stickers — as this study did. It’s possible that children eat different things on different days, so we need to make sure that we test them on multiple days of the week. It’s possible that they might change their behavior once, but then go back to their old ways, so we need to test responses over time.

It’s possible that handing out the cookie or apple personally might change behavior more than just leaving the choices out for display. If that’s the case, we need to stay hidden and observe unobtrusively. This matters because in the real world it’s probably not feasible to have someone handing out these foods in schools, and we need the methods to mirror what will most likely happen later. It’s also possible that the choices might differ based on whether children can take both the apple and the cookie (in which case they could get the sticker and the treat) or whether they had to choose one.

I point out all these things to reinforce that this type of research isn’t as simple as many might initially think. Without addressing these questions, and more, the work may be flawed or not easily generalized.

These difficulties are some of the reasons so much research on food and nutrition is done with animals, like mice. We don’t need to worry as much about I.R.B.s or getting a school on board. We don’t have to worry about mice noticing who’s recording data. And we can control what they’re offered to eat, every meal of every day. But the same things that make animal studies so much easier to perform also make them much less meaningful. Human eating and nutrition are typically more complex than anything a mouse would encounter.

Overcoming these problems and proving spectacular results in preteens are some of the reasons this study on cookies and apples, and others like it, are so compelling. The authors have transformed this work into popular appearances, books and publicity for the Food and Brand Lab.

But cracks began to appear in Mr. Wansink’s and the Food and Brand Lab’s work not long ago, when other researchers noted discrepancies in some of his studies. The numbers didn’t add up; odd things appeared in the data, including the study on apples and cookies. The issues were significant enough that JAMA Pediatrics retracted the original article, and the researchers posted a replacement.

The problems didn’t end there. As Stephanie Lee at BuzzFeed recently reported, it appears that the study wasn’t conducted on 8-to-11-year-olds as published. It was done on 3-to-5-year-olds.

Just as mice can’t be easily extrapolated to humans, research done on 3-to-5-year-olds doesn’t necessarily generalize to 8-to-11-year-olds. Putting an Elmo sticker on an apple for a small child might matter, but that doesn’t mean it will for a fifth grader. On Friday, the study was fully retracted.

Making things worse, this may have happened in other publications. Ms. Lee has also reported on a study published in Preventive Medicine in 2012 that claimed that children are more likely to eat vegetables if you give them a “cool” name, like “X-ray Vision Carrots.” That study, too, may be retracted or corrected, along with a host of others.

As a researcher, and one who works with children, I find it hard to understand how you could do a study of 3-to-5-year-olds, analyze the data, write it up and then somehow forget and imagine it happened with 8-to-11-year-olds. The grant application would have required detail on the study subjects, as well as justification for the age ranges. The I.R.B. would require researchers to be specific about the ages of the children studied.

I reached out to the authors of the study to ask how this could have happened, and Mr. Wansink replied: “The explanation for mislabeling of the age groups in the study is both simple and embarrassing. I was not present for the 2008 data collection, and when I later wrote the paper I wrongly inferred that these children must have been the typical age range of elementary students we usually study. Instead, I discovered that while the data was indeed collected in elementary schools, it was actually collected at Head Start day cares that happened to meet in those elementary schools.”

This is a level of disconnect that many scientists would find inconceivable, and I do not mean to suggest that this is the norm for nutrition research. It does, however, illustrate how an inattention to detail can derail what might be promising work. The difficulties of research in this area are already significant. Distrust makes things worse. The social sciences are already suffering from a replication problem; when work that makes a big splash fails to hold up, it hurts science in general.

We want to believe there are easy fixes to the obesity epidemic and nutrition in general. We want to believe there are simple actions we can take, like putting labels on menus, or stickers on food, or jazzing up the names of vegetables. Sadly, all of that may not work, regardless of what advocates say. When nutrition solutions sound too good to be true, there’s a good chance they are.

The quality of provider-offered Medicare Advantage plans

Earlier this year, with colleagues Zoe Lyon and Garret Johnson, I published a paper in Health Affairs on the quality of provider-offered (aka, vertically integrated) Medicare Advantage contracts,* comparing them to insurer-offered contracts. I wrote about that paper in an Upshot post:

[On a scale of 1 (worst) to 5 (best) stars] an average provider-offered plan has quality ratings that are about one-third of a star higher for both, after adjusting for factors that could confound the comparison, like socioeconomic status and the types and number of doctors where plans are offered.

Our study dug deeper to examine the kinds of quality enhancements available in provider-offered plans. Some aspects of quality are clinically focused. For instance, measures of preventive screening — like that for colorectal cancer — or management of chronic conditions assess the quality of care delivered by doctors and hospitals in a plan’s networks. Provider-offered plans perform somewhat better than insurer-offered plans in such areas.

Other aspects of quality pertain to customer service. In measures of complaints, responsiveness to customers and the enrollees’ overall experiences, provider-offered plans really shine. In each area of customer service we examined, provider-offered plans are rated one-half star higher than insurer-offered ones. (This is a big difference. For comparison, over half of plans are within one star of each other in overall quality.)

Today, joined by Yevgeniy Feyman, we have a new paper, published at BMJ Quality & Safety. It’s the same sample and analysis as the Health Affairs paper, but focused on more granular measures of quality.

You see, Medicare Advantage quality is captured by dozens of clinical and customer service related metrics. These are then rolled up into nine domains covering broad dimensions of quality, like rates of receipt of screenings, tests, and vaccines (for Part C) and drug pricing and patient safety (for Part D). These are further rolled up into an overall Part C and Part D quality score and, finally, to an overall Part C+D score. Everything is in the metric of stars (1-5).

The Health Affairs paper covered just the overall and domain level scores. The new BMJ Quality & Safety paper covers the finest-level metrics. (Our original submission to Health Affairs included both, but reviewers didn’t want so much detail. So, we yanked the fine level stuff, which is why we sought another venue to publish it. Welcome to academia.)

Given the nature of the data, it should be no surprise that our findings are broadly consistent with our prior work. Some examples:

Enrollees in provider-offered contracts are more likely to receive recommended colorectal cancer screening (difference=0.51 SD; p

In contrast, in two measures related to access and administrative performance, provider-offered contracts performed significantly worse than insurer-offered contracts. Provider-offered contracts tended to have more corrective actions taken due to access and performance problems (difference=0.50 SD; p

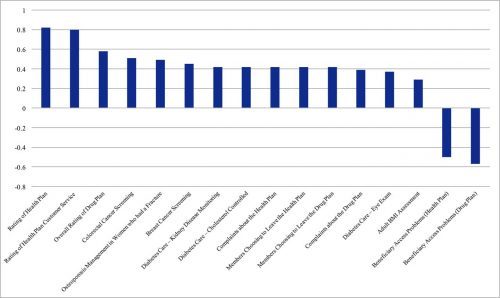

The following figure from the paper shows the adjusted** quality differences between provider-offered and insurer-offered Medicare Advantage contracts that were statistically significant (click to enlarge). Results are displayed in units of standard deviations. A positive value indicates that provider-offered contracts performed better than insurer-offered ones.

Both the Health Affairs and the BMJ Quality & Safety papers follow an earlier HSR publication on vertically integrated MA plans, by me, Roger Feldman, and Steve Pizer, with consistent findings.

* Under a single contract, an MA insurer can offer multiple plans. Quality reporting is at the contract level. Hence, so is our analysis. However, these details are not essential to convey the stylized facts to an Upshot audience. And stylized facts are all one can ever hope to impart. Nobody outside the wonkosphere knows what an “MA contract” is. Everybody thinks in terms of plans and insurers. So my Upshot piece used “plan” when “contract” would have been, technically, more precise. Don’t @ me. This is totally fine.

** Adjusters include the same set of covariates used in prior work: MA Herfindahl-Hirschman Index, county MA enrolment, benchmark payment rate, the proportion of other MA parent organisations that were provider offered, FFS Medicare standardised per capita costs and average beneficiary risk score, percentages of adult residents with at least a high school diploma and with at least 4 years of college, percentages of workers in manufacturing and in construction, poverty rate of those ages 65 and older, per capita income, the proportion of the elderly above 75 years old, urban or rural status, and physicians and hospital beds per 1000 people.

October 24, 2017

Healthcare Triage: The New Rules on Contraceptive Coverage

In a new rule about coverage of contraception, the Trump administration argues that birth control is bad for your health. But it’s a claim that doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. That’s the topic of this week’s Healthcare Triage.

This episode was adapted from a column I wrote for the Upshot. Links to further reading and sources can be found there.

Also – I’ve got a book coming out November 7. It’s called The Bad Food Bible: How and Why to Eat Sinfully. Preorder a copy now!!

Amazon.com

Barnes & Noble

Indiebound

iBooks

Kobo

Any local bookstore you might frequent. You can ask for the book by name or ISBN 978-0544952560

See me at the ECRI conference. It’s free!

I’ll be joining a session at the ECRI conference, which is being held on November 28-29 at Georgetown University (Location details and free registration at the conference page).

This conference is intended to enhance the national dialog on practice efficiency and institutional culture and its effects on care. My session will explore the important questions related to veterans health care, such as:

How is the military’s historic reliance on standardization as an efficient way to achieve ends, especially in complex situations such as warfare, adapted to care for veterans, especially those with complex conditions resulting from physical and mental trauma?

Does standardization lead to inefficient workflow with increased work burden and workarounds if the system is too rigid and how has the Veterans Health Administration taken a lead on this issue as the largest health system in the nation?

How are workflows impacted by interfaces in the Veterans Choice program which expands the need for coordination between the VA and civilian healthcare system?

I’ll be joined by the moderator Carolyn M. Clancy, MD, Deputy Under Secretary for Health for Organizational Excellence, Veterans Health Administration and fellow panelists Stephan D. Fihn, MD, MPH, FACP, FAHA , Director, Clinical System Development and Evaluation, Veterans Health Administration and Neil C. Evans, MD, Chief Officer, Office of Connected Care, Veterans Health Administration.

Lots of other great speakers at other sessions too.

October 23, 2017

Sometimes, when you’re responsible for others, it’s your job to let them be unfair to you

When I was an intern, in one of the first months of my residency, I walked into a patient room to see a child who was being admitted to the hospital. I had barely closed the door before the child’s mother started yelling at me. She was angry that they’d been waiting so long. She was angry because she felt like her child had been mishandled before admission. She was angry that he was in pain, and that no one had given him anything for it.

I was stunned. I had literally only learned about this patient five minutes before I had walked in the room. It had taken me only that amount of time to cross the hospital to see them. I started to defend myself, saying that it was unfair that she was angry at me. None of this was my fault.

This… did not defuse the situation. She lost it on me, screaming that we’d screwed up, that she was tired of being jerked around, and she wasn’t going to listen to excuses. I, being an idiot, tried to argue further. After all, she was blaming me for things I couldn’t control. Meanwhile, her child was in pain and crying in the bed.

I took a patient history as best I could, did a cursory exam, and left to place orders. Then I went to talk to my senior resident. I relayed to him about how ridiculous I thought it was that this mother treated me this way. I went on and on about how unfair it was. I said, “I try so hard to be a good doctor. I don’t understand why she was so unhappy with me.”

He said something which stuck with me, many years later. “She’s got a kid in the hospital, and you’re worried that she doesn’t like you?”

This poor woman was probably panicked out of her mind. She didn’t know what was wrong with her son. She felt like doctors had been screwing up left and right. Her child was crying, in pain, and she couldn’t make it go away. Of course she was angry; of course, she had to take it out on someone.

It was my job to be the receptacle for that anger. Over the course of my (limited) clinical practice, I have let countless parents yell at me. Almost every single time, I thought they were wrong on the facts, but I didn’t care. The only way I could help them was to let them get out their frustration. I’m a big boy. I’m a doctor. I can handle it.

This lesson has served me well as a parent, too. Many times, my children have been frustrated by school, by friends, or even by me or my wife. They snap. I could choose to fight with them, to prove to them that they’re wrong and I’m right. I could “win”. But I know I’ll lose in the end. Because sometimes people are just angry or upset, and they need to vent. I’m their dad. It’s my job. We’ll settle the facts at a later time. The world won’t end in the meantime because I “lost” an argument.

I’ve been watching a lot of news recently where people feel the need to fight. To respond. To be “right”. I don’t know who coined the phrase, “Do you want to be right, or do you want to be happy?” but it’s a mantra in our house. I try very, very hard in my personal life to make it the latter.

When you hold the power, sometimes you have to let others unload on you. It’s the only way to help some people; it’s all they have left. If you can’t handle that, don’t ever put yourself in the position of being responsible for other people’s lives. This applies to more than just medicine, of course.

Come work with me (job posting 1)

Colleagues and I are advertising for research data analysts. If that’s you, this is an opportunity to work with us at the Partnered Evidence-based Policy Resource Center (PEPReC).Though PEPReC is a center in the Veterans Health Administration, the position will be filled through Boston University.

Apply here. And watch this space for more job opportunities.

PS: Yes, the job posting has a typo: “SA” should be “SAS”.

October 20, 2017

SciShow Kids: Going to the Doctor’s Office with Dr. Aaron Carroll

A couple weeks ago, I took a trip to Missoula Montana to visit the other half of the company that makes Healthcare Triage. I appeared on a number of shows over there, which I’m sure will trickle out over the next few weeks.

This is SciShow Kids, and while it’s likely not aimed at the TIE audience, I wanted to post it here because it’s so damn cute. Enjoy!

Cost sharing reduction weeds: “Silver loading” and the “silver switcheroo” explained

Last week I alluded to ways that consumers could be protected from premium spikes resulting from the Trump Administration’s cessation of cost sharing reduction payments to Marketplace insurers — so called “silver loading” and the “silver switcheroo.” Margot Sanger-Katz wrote about these this week at the Upshot. Some additional details are provided in the following interview with Charles Gaba, who runs the website ACAsignups.net, which is the unofficial and widely cited tracker of Marketplace plan enrollment and related health coverage statistics and policy. Charles tweets at @charles_gaba.

Austin: A Trump Administration decision last week will cut cost sharing reduction (CSR) payments to Marketplace plans. Because those plans will have to pay CSRs anyway, they’ll need to raise premium revenue. But, you’ve been writing about one way they can do that that minimizes harm to some consumers — silver loading. What is silver loading?

Charles: That’s when an insurance carrier adds ALL of the CSR losses they expect to be hit with in 2018 onto the premiums of silver plans only (as opposed to spreading the cost out across all 4 metal levels).

Austin: That makes sense since CSRs are paid out for silver plans only. Let’s talk about how this affects consumers. There are two kinds of Marketplace consumers: subsidized consumers and unsubsidized consumers. Let’s take them separately. Can you explain how subsidized consumers are affected by the cessation of government CSR payments to insurers and how silver loading helps them, if at all?

Charles: When the CSR cost is loaded onto a Marketplace plan, it causes the premiums to go up substantially. However, since the amount of the subsidies enrollees receive is based on the cost of the 2nd least-expensive silver plan (the “benchmark plan”), that means if the benchmark premium increases, so does the subsidy. If the benchmark plan goes up 30%, the subsidies people receive generally goes up about 30% as well, matching the full-price premium increase.

If the CSR costs are spread out across ALL metal levels, then premiums might only go up, say, 20% across bronze, silver, gold and platinum. This means that subsidized enrollees won’t really do any worse or better as a result.

However, if ALL CSR costs are loaded onto silver plans only, they might go up 30% while bronze, gold and platinum plans only go up 10%. That means that a subsidized silver enrollee might suddenly find themselves able to get a gold plan for around the same or even less than the silver plan they’re on now. It should also mean enrollees on bronze, gold or platinum plans will see their rates drop slightly (or at worst only go up slightly).

Austin: Now, what about unsubsidized consumers? How could they be harmed by the Administration’s move and how does silver loading help them?

Charles: If a carrier loads any portion of the CSR cost onto the price of any plans, unsubsidized enrollees will have to pay the full cost of that increased premium, whether they’re on or off the Marketplace. Silver loading doesn’t really help them, although if the carrier loads all of the CSR cost onto silver plans, obviously that means bronze, gold & platinum enrollees won’t be hit with the extra CSR load. However, that also means unsubsidized silver enrollees will be hit with even more of the load.

There is, however, a more complex version of silver loading [about which more below].

Austin: Can just any insurer implement silver loading, or does it require some state action?

Charles: That seems to vary by state. Some state insurance commissioners have given very strict rules about how the carriers have to load the CSR cost; others required 2 sets of rate filings (one assuming CSRs are paid, one assuming they aren’t), but didn’t specify which route they had to take; and some didn’t give any guidance whatsoever, leaving it up to the carriers to figure it out.

Austin: Silver loading would seem to require some coordination. If only some insurers silver load and others don’t then the second cheapest plan might not be a silver loaded one. I wonder what will happen in states where the commissioner doesn’t coordinate how CSRs need to get loaded onto plans. Will insurers separately coordinate? Is it legal for them to do so?

Charles: I assume you’re talking about whether the insurers doing so privately would be considered collusion/price fixing, etc? I’m afraid I have no idea what legal authority either insurance commissioners or the carriers themselves have in this regard. I presume that the commissioners authority on this sort of thing is solid or that it varies from state to state. To date at least 35 states have silver loaded or are “silver switcharooing”, the more complex version of it that I referred to earlier.

Austin: Let’s get back to unsubsidized consumers. If they want to purchase a silver plan for the lowest possible price. What’s the work around you alluded to above?

Charles: If you’re in a “standard” Silver load state and are unsubsidized, you’re pretty much stuck looking at Gold or Bronze plans, since all Silver plans would have some CSR surcharge tacked on.

However, if you’re in one of the 13 “Silver Switcharoo” states, there’s a way of keeping a Silver plan without paying the CSR surcharge.

In those states, all of the CSR cost is loaded not just onto silver plans, but specifically onto silver plans available on the exchange only.

Under the ACA, some plans are offered both on and off the exchange, while others are only offered off the exchange (there aren’t any plans available on-exchange only). This means that in a Switcharoo state, you could have two different Silver plans: One available both on and off exchange (Silver A), the other available off exchange only (Silver B).

Let’s say that these plans are very similar and each costs $500/month on average this year, and each has the same number of enrollees at the moment.

In a normal Silver Load state, both plans might go up by $100/month due to the CSR load, so if you’re unsubsidized, you take the hit either way.

In a Silver Switcharoo state, Silver A might go up by $200/month but Silver B wouldn’t go up at all. If you’re currently on Silver A (whether you enrolled on or off the exchange), you would switch to Silver B to avoid getting hit with any CSR load.

In theory, this should result in nearly 100% of exchange enrollees being subsidized (up from around 84% today), while many unsubsidized enrollees move to off-exchange silver plans instead.

***

Charles has provided some additional explanation and resources at the following links:

Detailed explainer of Silver Switcharoo

An explainer of all various approaches to the CSR issue, by Charles, Dave Anderson, Louise Norris and Andrew Sprung

The state spreadsheet

An estimate of how many people will be impacted by the various approaches in each state

Healthcare Triage News: Trump Cuts ACA Cost-sharing Payments, Lawsuits Incoming

This week, Donald Trump’s administration continued to try and undermine the Affordable Care Act by terminating cost-sharing payments to insurers. Ironically, in the long run, this will increase premiums, which will mean the federal government is on the hook to pay subsidies for Obamacare marketplace enrollees with lower incomes.

This video was adapted from a post by Nick here at TIE. You might also want to read Nick’s and Craig Garthwaite’s NY Times Op-ed.

October 19, 2017

JAMA Forum: What Do Medicare Advantage Networks Look Like?

Networks, and their narrowness, seems like a significant concern. Yet we know next to nothing about Medicare Advantage networks. That’s not so good. More about that in my latest JAMA Forum post.

In the absence of more comprehensive analysis, we should not be reassured that regulators are managing Medicare Advantage networks for quality and efficiency. Although the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) imposes adequacy requirements based on time and distance criteria for Medicare Advantage physician networks, those requirements are routinely applied only when plans enter markets, and it remains unknown whether the criteria are met months and years after market entry. Indeed, in a 2015 report, the Government Accountability Office recommended more periodic reviews and verification of availability of physicians and hospitals within networks. Earlier this year the Department of Justice reached a settlement with 2 Medicare Advantage plans over charges of misrepresentation of their networks to regulators.

Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers