Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 117

November 29, 2017

Healthcare Triage News: Lots of Children Are About to Lose Their Health Coverage

Budget authorization for the Children’s Health Insurance Program in the US ran out a couple of months ago, and there’s no reauthorization in sight. A LOT of kids are insured through this program. Aaron runs you through what’s about to happen.

Where Is the Prevention in the President’s Opioid Report?

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2017, The New York Times Company). It also appeared on page A15 of the print edition on November 28, 2017.

It’s a shame that President Trump’s opioid commission said little about demand-side prevention.

It’s a lot less costly (both in dollars and in lives disrupted) to stop opioid misuse before it starts than to deal with its aftermath. And many prevention programs are cost effective, according to an analysis by the Washington State Institute for Public Policy.

The report from the commission last month emphasized limiting supply much more than demand — targeting opioid sources like prescriptions and the black market. That’s important, too.

But among the report’s 56 recommendations, only two aim to prevent people from seeking out opioids for no medical purpose: an advertising campaign and a structured discussion with a health professional. Neither approach has particularly strong science behind it. We wrote about the weakness of ad campaigns this month.

The other demand-side prevention approach recommended by the commission isn’t a lock either. The approach — called screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment, or S.B.I.R.T. — begins with an assessment to identify people who may already be engaged in risky use of opioids or other substances. This could occur during a regular doctor’s visit. Those found to be using drugs in high-risk ways are given advice and feedback or referral to treatment, if warranted. This could prevent progression to worse outcomes of opioid misuse like addiction and overdose, but wouldn’t prevent misuse of opioids before it starts.

“The brief intervention part of S.B.I.R.T. has had success at changing problem drinking, but little with drug use,” said Keith Humphreys, a professor at Stanford University School of Medicine who advises governments on drug prevention and treatment policies. “Referral to treatment has been a failure across the board. Almost no one follows up.”

Though this screening-referral approach has been applied to patients of all ages, the report emphasizes its use in school-based settings. It draws examples from programs in Massachusetts for middle-to-high school students and in Ohio for college students. This leaves out useful prevention programs for younger children and older adults. It’s worth engaging these populations, too.

Though few children below middle-school age use or misuse opioids, some programs aimed at them can prevent their use at older ages, by identifying risk factors and countering them. For example, a favorable attitude toward substance use — either within the family or by children directly — increases the risk that a child will later get into trouble with addictive drugs, tobacco or alcohol. Other risk factors are family conflict, poor peer relationships or difficulty in school. Community characteristics like deterioration of physical infrastructure; high rates of mobility into and out of the area; and easy availability of opioids are also risk factors.

To counteract those risks, these programs aim to increase “protective factors,” such as meaningful involvement in school, family or community activities; recognition for achievement; coping skills for dealing with stress and emotions; and a social environment that conveys an expectation of not using drugs.

There are evidence-based programs that address risk and protective factors, even for young children. The Nurse Family Partnership sends nurses on home visits with first-time mothers. The visits include education to improve pregnancy and infant health and development, and to strengthen parenting skills. One randomized trial of the program followed children for 12 years and another for 15 years. Both studies found the program reduced a host of problematic behaviors, including those related to drugs and alcohol.

Another early elementary school-based program, the Good Behavior Game, also has some solid science behind it. The program rewards children for good behavior during classroom instruction. A randomized trial found it reduces rates of alcohol and drug use in young adulthood among males. Another test involving the Good Behavior Game showed it reduces use of cocaine and heroin.

By strengthening basic capacities of emotional management, social skills, decision-making, and social connections to parents and the community, programs like these help children and teenagers avoid drug misuse. But they also help with everything else in their lives. In this sense, we make a mistake when we think about preventing drug use as separate from addressing problems like bullying, dropouts or suicide. Providing children from a young age with certain basic skills and connections can help address all these issues.

“Prevention programs usually focus on one problem, like illicit drugs or smoking or school failure or obesity or bullying or depression,” Mr. Humphreys said. “But all those problems have common risk and protective factors, and targeting those brings benefits across the board for kids.”

Other programs for middle-to-high-school-aged students have solid evidence of effectiveness, particularly ones that engage entire communities in a shared effort. For example, the Communities That Care program builds coalitions in a community and provides tools to make decisions about the best evidence-based prevention programs.

A randomized trial across 24 small towns that followed about 4,000 children from fifth to 12th grade found encouraging results: Children in the Communities That Care program were a third less likely to take up alcohol or cigarettes in middle school, making them less likely to progress to other drugs, including opioids.

Parents are important, too, of course, and there are evidence-based drug-use prevention programs that involve them. One program — the Strengthening Families Program: For Parents and Youth 10–14 — aims to enhance parenting skills and adolescents’ ability to refuse drugs. Several studies found it reduces alcohol and drug use through young adulthood.

Finally, we should not overlook adults. Most drug experimentation occurs in young adulthood. In 2015, nearly 40 percent of adults in the United States reported using prescription opioids. Such use is most often for medical purposes, but 5 percent reported misusing them and 1 percent had use disorders.

For these people, workplace drug testing is a worthwhile approach. When the Department of Defense made drug use grounds for potential dismissal from service, positive tests fell, Mr. Humphreys told me. The rarity of drug-caused accidents in industries that test employees (like aviation) further suggests that this is a good strategy.

There are many evidence-based prevention programs that could be usefully applied to the opioid crisis. The commission’s report mentions some — including many of those described above — but it stops short of recommending any.

November 28, 2017

How I Lost Weight and Learned to Love Thanksgiving Again

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2017, The New York Times Company) last week. I didn’t get it up because of Thanksgiving. Enjoy it now. You might also like my new book, The Bad Food Bible: How and Why to Eat Sinfully, which is available in stores!

In our house, there are no pictures of my wife and me that are more than a few years old.

When I was a medical resident, nearly two decades ago, I didn’t take very good care of myself. I was a pediatrician, and I counseled patients and parents all the time about how to eat right and get enough exercise. But I couldn’t seem to figure that out for myself. I gained a lot of weight, and so did my wife, Aimee.

After our second child was born, Aimee decided she needed to make a change. She told me she was going to try Weight Watchers. Since it seemed silly for us to prepare two meals at a time, I decided to join her.

It worked. Weight Watchers then was mostly focused on fat reduction, calorie counting and increased fiber. We both lost weight. I didn’t lose all that I wanted to, but it was certainly an improvement. Unfortunately, it was hard to keep sticking to the program. There were too many days I was hungry. I became too obsessed with “low fat,” as fat seemed to be how “points” were calculated. (Today, Weight Watchers points focus on calories, sugar, fat and protein.)

Years later, when I decided to try to lose weight again, I focused on exercise. I made it through the torments of P90X, P90X3 and Insanity. Each workout regimen had its own diet plan, with a list of foods to avoid. I stuck to none of them for more than four or five months. They were too hard, and after initial success, my weight loss stalled.

Most recently, I tried to go “low-carb.” I became convinced, by reading books and studies, that carbohydrates were the true danger, not fats. I eliminated sugar from my diet almost completely. Once again, my weight dropped, but it eventually stopped falling.

My experience is not abnormal. Studies of diets show that many of them succeed at first. But results slow, and often reverse over time. No one diet substantially outperforms another. The evidence does not favor any one greatly over any other.

That has not slowed experts from declaring otherwise. Doctors, weight-loss gurus, personal trainers and bloggers all push radically different opinions about what we should be eating, and why. We should eat the way cave men did. We should avoid gluten completely. We should eat only organic. No dairy. No fats. No meat. These different waves of advice push us in one direction, then another. More often than not, we end up right where we started, but with thinner wallets and thicker waistlines.

I’m a physician and researcher with a particular interest in analyzing dietary health research, and even I get dizzy with the different perspectives on something as seemingly simple as the benefits of brown rice or the dangers of red meat. This is one reason I’ve decided to focus much of my writing on dietary health. I want to be able to advise my patients about what healthful eating looks like, and eat that way myself.

These conflicting opinions about nutrition have one thing in common: the belief that some foods will kill you — or, at least, that those foods are why you’re not at the weight you’d like to be. This is an attitude about food that actually has its roots in an earlier and opposite idea — that some foods can keep us from dying (think of sailors avoiding scurvy by eating citrus). Indeed, some of the earliest “expert” advice about food was predicated on the notion that some foods can save us.

When many more Americans were malnourished than are today, making sure they got more of foods containing things like vitamin B and C made sense. Today, the vast majority of people in the United States are not suffering from vitamin or nutritional deficiencies. Advice is usually delivered in terms of deprivation, not supplementation.

Much of this advice comes in the form of moralizing. But by making so much of our focus on what we’re doing “wrong,” we’ve removed much of the joy from eating and cooking. I made sure to avoid negative tones a couple of years ago when I drew up a manifesto/road guide we called simple rules for healthy eating. They include the idea that you aren’t going to avoid all processed foods, but you might try to limit them. The one I felt most passionately about was No. 7 — “Eat with other people, especially people you care about, as often as possible.” But lately, I’ve been thinking that No. 2 — “Eat as much home-cooked food as possible” — may be the most important.

I’ve recently been learning more about cooking theory — not so much following recipes, but understanding why those recipes work. A favorite guide in this quest is “Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat” by Samin Nosrat. Right there in the title are two “forbidden” elements. They’re also some of the main reasons good food tastes good.

The home-cooked food rule probably did more than any other to help Aimee and me get down to reasonable weights. Today, we’re much happier with how we look and feel. There are pictures of us looking happy in recent years around the house. Thanksgiving has reclaimed its mantle as my favorite holiday, because it’s so centered on food and family.

And yet. While I’ve adopted a much healthier attitude toward food in general, I sometimes find myself slipping into old habits. These last few months, I’ve been trying to lose weight again. I’m not obese, and I’m healthy. But my weight and height place me in the “overweight” category, and I think I could be thinner. As before, I tried going low-carb. I lost weight initially, then hit a plateau. I’ve been getting frustrated.

I was complaining of this to Aimee last week when my oldest child, Jacob, asked me why I was dieting. He couldn’t understand the point. I had no answer. I don’t think it will make me healthier or make me live longer. It won’t improve my quality of life. I won’t be in better shape. My clothes would fit the same. I’m not even sure anyone would see a difference.

I’m still too liable to think that being thin is the same thing as being healthy. I’m still too inclined to think that dieting is the same as healthful eating. Neither are true. Too often I’m chasing some imagined ideal that has no real-world consequences. My other son, Noah, has my physique and may someday find it all too easy to put on pounds. What message am I sending to him when I obsess over the number on the scale?

Jacob’s wiser than me. I’m still learning. One theme of my Upshot articles is that we should weigh the benefits and the harms in any health decision. When it comes to food, too often we focus only on the latter. When my daughter, Sydney, made cupcakes last night and asked me to try one, I did. The joy it brought her, and me, was worth it.

Healthcare Triage: The US Health Care System Needs Immigrants

By any objective measure, the United States doesn’t train enough medical doctors to meet the nation’s needs. That means graduates from other countries are needed. Aaron takes a look at foreign medical graduates, an essential element of America’s health care system.

This episode was adapted from a column I wrote for the Upshot. Links to further reading and sources can be found there.

November 22, 2017

Turkey doesn’t make you sleepy. IT DOESN’T.

I’m putting this up every year until you all stop saying it. Enjoy. And Happy Thanksgiving!

If you like this, you’ll also love my new book The Bad Food Bible. Go buy it!

November 21, 2017

Healthcare Triage: Teen Suicide Rates Are Rising, but Prevention is Possible

Rates of teen suicide are rising, and rates for girls are higher than any time in the last 40 years. There are a number of ways to address this problem, but why aren’t we using evidence-based approaches to the problem?

This episode was adapted from a column I wrote for the Upshot. Links to further reading and sources can be found there.

Why aren’t men in medicine getting outed for sexual harassment?

Many powerful men in journalism, entertainment, and politics are being exposed as sexual harassers. But we are not seeing a wave of similar events in medicine. Why not?

Because sexual harassment doesn’t happen in medicine? Hahahaha.

Because medicine has exceptionally strong secrecy norms? I have heard people say, “But he’s a doctor” (meaning, “one of us”) as if that were some kind of reason for keeping a scandal in-house.

Because journalism, entertainment, and politics are celebrity cultures? Perhaps complaints of harassment are lodged at similar rates in all industries, but we only learn about them when the perpetrator works in front of a camera.

Because the reputational costs to a news organization of having a harasser on-camera are a lot higher than the costs to a hospital of having a doctor who puts his hands on nurses? One gets fired, the other gets reprimanded.

Because the guild structure of medicine means that doctors are in a seller’s market for their labour? Actors, journalists, and politicians are easily replaced, whereas it is amazingly hard to hire a child psychiatrist, let alone a transplant surgeon. Doctors are therefore less likely to get fired for any cause.

Or perhaps it is just a matter of time before the revolution comes to medicine.

November 20, 2017

Mass shootings and the future: Update

On October 1st, 2017, the most lethal mass shooting in American history occurred in Las Vegas, NV. What has happened and what hasn’t happened since Las Vegas?

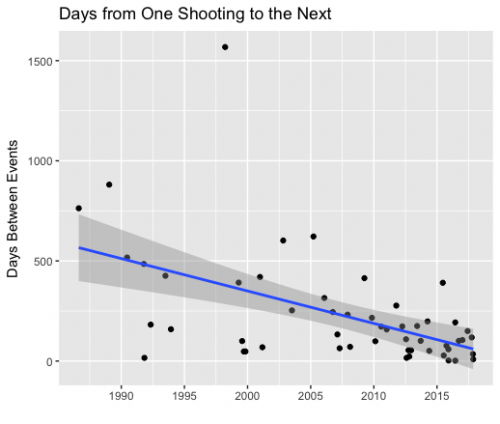

What has happened is that in the 50 days since Las Vegas there have been two more shootings that killed five or more people (San Antonio, TX, and Rancho Tehama, CA). If you sense that such shootings are becoming more frequent you are correct. The Figure below plots the number of days between successive mass shootings. The time between successive mass killings is decreasing. Alternatively, we can say that the frequency of mass shootings is steadily increasing.*

Decreases in the number of days between successive mass shootings (5 or more deaths).

What hasn’t happened is any regulation to control the technology that produced the extraordinary casualty rate in Las Vegas. The shooter was able to convert his automatic rifles into functional machine guns using legally available conversion kits (so-called “bump stocks”). These kits remain legal and there is no longer even public discussion of regulating them. There is no reason why a future mass killer cannot repeat the Las Vegas death toll.

Perhaps the Las Vegas death toll is near the limit of what can be achieved with contemporary small arms. However, in my post on Las Vegas, I noted that

the effectiveness of small arms will continue to improve. Current arms automate most of the loading of firearms, but foreseeable technology will also automate their aiming and facilitate their remote operation. If no limits are set on civilian access to continuously improving weapons technology, we should expect to see massacres with 100s of deaths.

The Future of Life Institute has produced an 8-minute video that makes the same point. Please take a moment and watch it.

This is science fiction, but it is near-future sci-fi in that it describes applications of currently available technology. The autonomous weapons in the video are likely illegal because they are explosive devices, which are regulated more strictly than firearms. However, if the drone’s charge propelled a metal disc — or if the drone simply carried a bullet in a short barrel — it’s not clear that the technology would be illegal.

In my post, I argued that

At some point, continued increases in the frequency and scale of mass shootings become incompatible with ordinary civic life.

Unless we either prevent the development of autonomous weapons or somehow limit them exclusively to the military, they will be used by terrorists and other mass killers.

*Similarly, the time between new records in the numbers killed during shootings also appears to be decreasing. Twenty-two people were killed in Killeen, TX, on October 16, 1991. Then 32 people were killed in Blacksburg, VA, on April 17, 2007 (15.5 years after Killeen). Then 37 people were killed in Newtown, CT, on December 14, 2012 (5.7 years after Blacksburg). Then 49 people were killed in Orlando, FL, on June 12, 2016 (3.5 years after Newtown). Then 58 in Las Vegas on October 1, 2017 (1.3 years after Orlando). It’s a short series, but it suggests that the Las Vegas total may be exceeded before the end of 2018.

November 16, 2017

Healthcare Triage News: The ACA Insurance Exchanges Are Open! Go Get Insured!

While Obamacare is has been under legislative threat all year, it’s still the law of the land, which means the exchanges are open for business for 2018. So if you don’t get insurance through your employer or Medicare or the VA, you should be shopping for your individual insurance coverage at the exchanges. So get to http://www.healthcare.gov, and get to shopping!

The tradeoff here is both simple and brutal.

“Republicans want to pay for a permanent corporate tax by taking insurance from millions of people. Is that who we are as a nation?”

That’s the end of my latest op-ed in the Washington Post. Here’s the beginning.

To finesse the tricky politics and brutal math of tax reform, Senate Republicans now say that they want to repeal the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate. For Republicans, repeal would be a trifecta: a blow to Obamacare, a money-saver for the federal government and a way to finance a permanent cut to the corporate tax rate.

Republicans are right about all of this. What they haven’t highlighted, however, are the tradeoffs: the estimated 13 million people who will lose insurance if the mandate is repealed. Is the country really better off if millions of people forgo medical care, and millions more go bankrupt, so that corporations can pay lower taxes? That’s not a rhetorical question. Those are the stakes of the game.

It’s actually worse than my op-ed suggests. In a smart post, Bob Laszewski explains why eliminating the mandate while loosening the restrictions on short-term plans “would be devastating for those in the unsubsidized middle class who would not be able to afford coverage once they got sick.”

Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers