Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 122

October 12, 2017

Mass shootings, technology, and the future

Every so often, an American shoots a large group of strangers in a public setting, and then is shot or, more often, shoots himself. The effect of these events on American gun policy has been surprising. Ross Douthat observed that

We… keep having a debate over guns in the United States; it’s just that the side that’s convinced that new regulations will prevent another Newtown or Orlando or Las Vegas keeps on losing the argument.

Douthat is absolutely right about which side has been losing. In the last decade, regulations on the sale, ownership, and carrying of firearms in the US have been reduced, not increased. It’s open to question, however, how long this can continue.

The LA Times has a list of shootings of five or more people since 1984. By their count, there have been 52 such events, accounting for 537 deaths, in the 34 years since 1984. This is about 15 deaths per year, which is 0.04% of the 34,000 annual American firearms deaths. The likelihood of dying in a mass shooting is about one-third that of dying by lightning strike and about one-sixth that of dying in a flood. Americans are killed by guns primarily through accidents, ‘non-mass’ homicides, and suicides, not mass shootings.

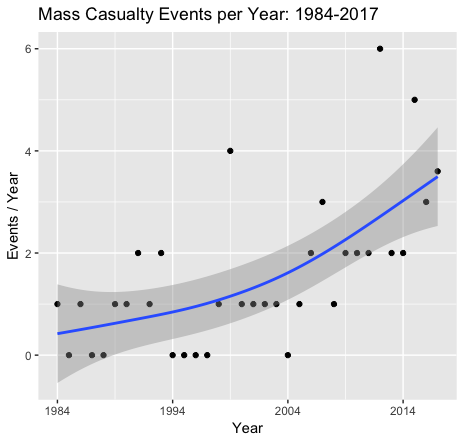

Having noted this, the frequency of mass shootings per year is increasing (equivalently, the time from one mass shooting to the next is decreasing).

Data from the LA Times as of October 1, 2017. The data point for 2017 is the projected number events for the entire year.

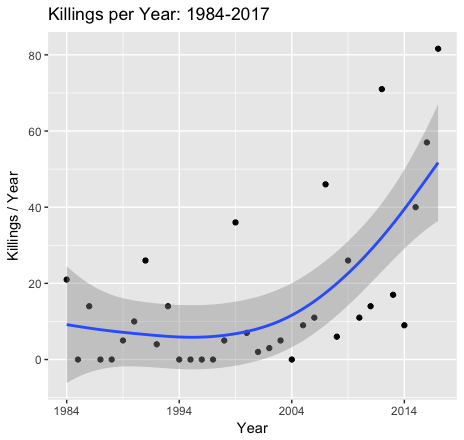

There were 9 mass shootings in the 10 years from 1984 to 1993 compared to 28 from 2008 until today. The annual death toll has also been rising, even faster than the increase in the number of mass shootings. There were 94 deaths from 1984 to 1993 compared to 319 from 2008 until today.

Data from the LA Times as of October 1, 2017. The total killings for 2017 is the projected number events for the entire year.

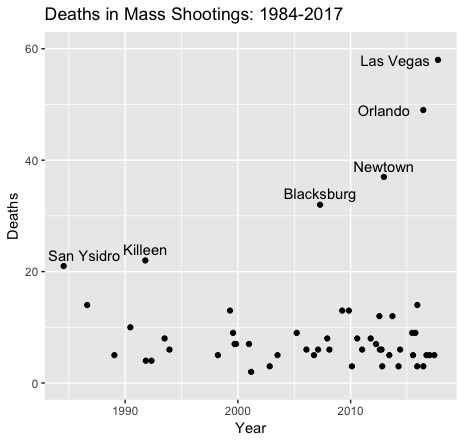

If you look at a scatter plot that includes all 52 events, there appear to be two classes of mass shootings.

Data from the LA Times as of October 1, 2017.

There has been a profusion of shootings involving 5 to 19 deaths at the bottom of the graph. Above that is a series of ultra casualty events (which I have labelled by the city in which they occurred). The death rate in these massacres has almost tripled since 2000.

Why is the scale of the extreme events increasing? One reason is technology. Modern small arms are highly lethal, portable, and affordable. Lethality is a combination of a weapon’s rate of fire, magazine capacity, accurate range, and the trauma inflicted by light-weight high-velocity rounds. Modern weapons are so effective that a single armed man targeting a crowd can inflict casualty rates that are reminiscent of the Battle of the Somme, rather than a bar fight. The editors of the New England Journal of Medicine comment that:

readily available high-powered modern weaponry makes mass killing easy for a determined killer, even an inexperienced one. [In Las Vegas], the magnitude of the killing could have been far greater. Given his position and his firepower, the shooter could have killed thousands…

I doubt that the Las Vegas shooter could have killed thousands, but I am certain that the effectiveness of small arms will continue to improve. Current arms automate most of the loading of firearms, but foreseeable technology will also automate their aiming and facilitate their remote operation. If no limits are set on civilian access to continuously improving weapons technology, we should expect to see massacres with 100s of deaths.

I do not want to predict that Americas will eventually act to reduce civilian access to highly lethal small arms. As Douthat noted, that prediction loses. But on current trends, it is not clear what the alternatives are. We do not know how to predict who will commit mass murder. There are handwaving discussions about improving mental health care, which might help at the margin, except that no one is actually serious about implementing improved care.

The industrial revolution forced the military to abandon mass formations. Infantrymen are now camouflaged, armoured, and above all dispersed. Life in cities — and civilian life generally — involves people gathering in public spaces. At some point, continued increases in the frequency and scale of mass shootings become incompatible with ordinary civic life.

October 11, 2017

Can the U.S. Repair Its Health Care While Keeping Its Innovation Edge?

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2017, The New York Times Company). It was jointly authored by Aaron Carroll and Austin Frakt and also appeared on page B2 of the October 10, 2017 print edition.

The United States health care system has many problems, but it also promotes more innovation than its counterparts in other nations. That’s why discussions of remaking American health care often raise concerns about threats to innovation.

But this fear is frequently misapplied and misunderstood.

First, let’s acknowledge that the United States is home to an outsize share of global innovation within the health care sector and more broadly. It has more clinical trials than any other country. It has the most Nobel laureates in physiology or medicine. It has won more patents. At least one publication ranks it No. 1 in overall scientific innovation.

Strong promotion of innovation in health care is one reason the United States got as far as it did in our recent bracket tournament on the best health system in the world. Though the United States lost to France, 3-2, in the semifinals, it picked up its two votes in part because of its influence on innovation, which can save lives in the United States and throughout the world.

Now we shouldn’t delude ourselves into thinking Americans are inherently more innovative than people in other countries. In fact, many American innovators are immigrants who may or may not be citizens. Many technological and procedural breakthroughs in medicine have occurred in other countries.

Rather, the nation’s innovation advantage arises from a first-class research university system, along with robust intellectual property laws and significant public and private investment in research and development.

Perhaps most important, this country offers a large market in which patients, organizations and government spend a lot on health and companies are able to profit greatly from health care innovation.

The United States health care market, through which over one-sixth of the economy flows, offers investors substantial opportunities. Rational investors will invest in an area if it is more profitable than the next best opportunity.

“The relationship between profits and innovation is clearest in the biopharmaceutical and medical device sectors,” said Craig Garthwaite, a health economist with Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management, and one of the judges in our tournament. “In these sectors, firms are able to patent innovations, and we have a good sense of how additional research funds lead to new products.”

High brand-name drug prices, along with generous drug coverage for much of the population, fuel an expectation that large biopharmaceutical research and development investments will pay off. Were American drug prices to fall, or coverage of prescription drugs to retrench, the drug market would shrink and some of those investments would not be made. That’s a potential innovation loss.

This is not mere theory, economists have shown. Daron Acemoglu and Joshua Linnfound that as the potential market for a type of drug grows, so do the number of new drugs entering that market. Amy Finkelstein showed that policies that made the market for vaccines more favorable in the late 1980s encouraged 2.5 times more new vaccine clinical trials per year for each affected disease. And Meg Blume-Kohout and Neeraj Sood found that Medicare’s introduction of a drug benefit in 2006 was associated with increases in preclinical testing and clinical trials for drug classes most likely affected by the policy.

Health care innovation can have direct benefits for health, well-being and longevity. A study led by a Harvard economist, David Cutler, showed that life expectancy grew by almost seven years in the second half of the 20th century at a cost of only about $20,000 per year of life gained. The vast majority of gains were because of innovations in the care for high-risk, premature infants and for cardiovascular disease. These technologies are expensive, but other innovation can be cost-reducing. For instance, in the mid-1970s, new dialysis equipment halved treatment time, saving labor costs.

Even with those undeniable improvements, there are questions about the nature of American innovation. Work by Mr. Garthwaite, along with David Dranove and Manuel Hermosilla, showed that although Medicare’s drug benefit spurred drug innovation, there was little evidence that it led to “breakthrough” treatments.

And although high prices do serve as incentive for innovation, other work by Mr. Garthwaite and colleagues suggests that under certain circumstances drug makers can charge more than the value of the innovation.

The high cost of health care, an enormous burden on American consumers, isn’t necessarily a unique feature of our mix of private health insurance and public programs. In principle, we could spend just as much, or more, under any other configuration of health care coverage, including a single-payer program. We spend a great deal right now through the Medicare program — often held out as a model for universal single-payer.

Despite the fact that traditional Medicare is an entirely public insurance program, there’s an enormous market for innovative types of care for older Americans. That’s because we are willing to spend a lot for it, not because of what kind of entity is doing the spending (government vs. private insurers).

In fact, some question whether the innovation incentive offered by the health care market is too strong. Spending less and skipping the marginal innovation is a rational choice. Spending differently to encourage different forms of innovation is another approach.

“We have a health care system with all sorts of perverse incentives, many of which do little good for patients,” said Dr. Ashish Jha, director of the Harvard Global Health Institute and the other expert panelist who favored the U.S. over France, along with Mr. Garthwaite. “If we could orient the system toward measuring and incentivizing meaningfully better health outcomes, we would have more innovations that are worth paying for.”

Naturally, the innovation rewarded by the American health care system doesn’t stay in the U.S. It’s enjoyed worldwide, even though other countries pay a lot less for it. So it’s also reasonable to debate whether it’s fair for the United States to be the world’s subsidizer of health care innovation. This is a different debate than whether and how the country’s health care system should be redesigned. We can stifle or stimulate innovation regardless of how we obtain insurance and deliver care.

“We have confused the issue of how we pay for care — market-based, Medicare for all, or something else — with how we spur innovation,” Dr. Jha said. “In doing so, we have made it harder to engage in the far more important debate: how we develop new tests and treatments for our neediest patients in ways that improve lives and don’t bankrupt our nation.”

October 10, 2017

Healthcare Triage: Medicaid And The Opioid Epidemic – Correlation is not Causation

Recently, Ron Johnson (R) of Wisconsin launched an investigation into whether the Medicaid expansion that was part of Obamacare caused America’s opioid crisis. Healthcare Triage has looked at the evidence, and we think it’s a dubious claim.

This episode was adapted from a column Austin and I wrote for the Upshot. Links to sources and further reading can be found there.

Also – I’ve got a book on that topic coming out November 7. It’s called The Bad Food Bible: How and Why to Eat Sinfully. You can preorder it right now, and it’s also the topic of this week’s Healthcare Triage.Preorder a copy now!!

Amazon.com

Barnes & Noble

Indiebound

iBooks

Kobo

October 6, 2017

The Trump Administration and Contraception Coverage

This morning, HHS released two rules that will allow many more employers to exclude contraception from the insurance plans they offer to their employees. The first expands an existing religious exemption; the second allows employers to exempt themselves by invoking a freestanding “moral objection.”

As I explained when a draft of the rules first leaked, I think there’s a good chance that the courts will stop them from taking effect. Procedurally, the administration still hasn’t offered a cogent explanation for why it thinks it can amend an existing rule, and adopt a new one, without going through notice and comment. Substantively, HHS doesn’t have the authority to excuse employers from complying with a statute because they have moral objections.

The final rules have changed somewhat since I wrote my initial posts. I’ve therefore decided to compile those older posts here into one longer post that I’ve updated to account for the changes. I’ve also included some thoughts about what we should expect to see next and why the administration has issued rules with such obvious legal vulnerabilities.

The Procedural Problem

The rules are styled as “interim final rules,” which means that they go into effect today. And, as David Anderson has explained, it’ll only take a hot minute for employers who wish to take advantage of the expanded accommodation to adjust their offerings. So if you’re thinking about getting an IUD, now might be a good time to get one.

The Administrative Procedure Act, however, requires new rules to go through notice and comment before they’re adopted. It’s a cumbersome process, often taking a year or more, but it’s not optional. So what’s HHS’s justification for skipping notice and comment?

The agency offers two rationales, neither of which is convincing. First, the agency says that it has statutory authorization—specifically, in 26 U.S.C. §9833, 29 U.S.C. §1191c, and 42 U.S.C. §300gg-92—to skip notice and comment. (This isn’t an original claim; Obama’s HHS made it too.) But these provisions are just generic grants of rulemaking authority. They allow the Secretary to “promulgate such regulations as may be necessary or appropriate to carry out” his various responsibilities, including “any interim final rules as the Secretary determines are appropriate.”

The courts, however, don’t read generic grants of rulemaking power to displace the APA’s background rules. If Congress had really meant to license the Secretary to ignore public participation whenever he wanted to, Congress would have said so clearly. So yes, the Secretary can issue regulations, even interim final regulations, but only when he acts consistently with the APA.

Second, HHS says it has “good cause” under the APA to skip notice and comment. Good cause exists when notice and comment is “impracticable, unnecessary, or contrary to the public interest.” That’s a flexible standard, but the courts have said that it “is to be narrowly construed and only reluctantly countenanced,” with its use “limited to emergency situations.”

So what’s the emergency here? HHS’s explanation is somewhat rambling, but it points out that Obama’s HHS also issued two interim final rules relating to the contraception mandate. Now, that’s true—but only because the agency faced a tight statutory deadline and, later, a Supreme Court order in Wheaton College requiring a rule change. Those are classic reasons to find good cause. Indeed, that’s why the D.C. Circuit brushed back an earlier challenge to one of HHS’s interim final rules: “the modifications made in the interim final regulations are minor, meant only to ‘augment current regulations in light of the Supreme Court’s … order.’”

Here, there’s no deadline and no court order requiring a rule change. (Although the Supreme Court exhorted HHS and religious organizations to resolve their differences in Zubik v. Burwell, and although the Seventh Circuit has recently done the same, that’s not the same thing.) What’s more, the Obama administration did invite feedback before it initially adopted its religious accommodation— and received more than 400,000 comments in response.

In a twist, Trump’s HHS wants to exploit that deluge of comments to justify changing the accommodation without public feedback. “[T]he [agency] received more than 100,000 comments on multiple occasions,” including “extensive discussion about whether and by what extent to expand the exemption.”

If these new rules were just minor tweaks of the prior accommodation, HHS’s explanation might hold water. But they aren’t. They break with prior law in at least three big ways. First, they extend the accommodation any and all organizations, not just to religious nonprofits (like Catholic hospitals and universities) and privately held corporations (like Hobby Lobby). Second, they allow employers to drop contraception coverage without filing federal paperwork, potentially complicating efforts to guarantee alternative coverage for employees. Third, unspecified “moral” objections—not just religious ones—are now enough to justify relieving employers of their statutory obligations under the ACA.

HHS may have received hundreds of thousands of comments about contraception, but it hasn’t received focused feedback on these specific proposals. That’s likely to be a problem in court. The D.C. Circuit, in particular, can be really persnickety when agencies don’t provide adequate notice of a proposed change, even where earlier rounds of notice and comment seem to cover the issue. (I’ve been critical of the case law around good cause, and I have some sympathy with HHS’s position here. But the law is what it is.)

At the end of the day, HHS’s justification boils down to a concern with “delay[ing] the ability of … organizations and individuals to avail themselves of the relief afforded by these interim final rules.” The agency instead wants “to provide immediate resolution to this myriad of situations rather than leaving them [sic] to continued uncertainty, inconsistency, and cost during litigation challenging the previous rules.” But that’s just another way of saying that the rule is so important that it has to be rushed out the door without hearing what the public has to say about it.

That’s not how it works. Notice and comment always causes the delay of important rules. Notice and comment always extends any existing uncertainty. And yet the APA still requires public feedback—especially on rules that spark public controversy. If the administration really has a genuine “desire to bring to a close the more than five years of litigation,” why invite a lawsuit over a procedural question? Where’s the fire?

The Substantive Problem

HHS’s rule allowing employers with “moral objections” to decline to offer contraception is more deeply flawed. To date, the lawsuits over the contraception mandate have focused on the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), which requires the federal government to avoid placing burden on the exercise of religion. It’s RFRA that gives HHS the power to craft a religious exemption for contraception coverage.

RFRA, however, does not extend to moral objections without a basis religious exercise. As such, RFRA can’t supply authority for HHS to exempt employers with moral objections to the contraception mandate.

So where does the agency find that authority? HHS points to section 2713(a)(4) of the Public Health Service Act, which is codified here:

A group health plan and a health insurance issuer offering group or individual health insurance coverage shall, at a minimum provide coverage for and shall not impose any cost sharing requirements for …

(4) with respect to women, such additional preventive care and screenings [beyond those rated “A” or “B”] as provided for in comprehensive guidelines supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration for purposes of this paragraph.

Does that look to you like it allows HHS to craft exemptions due to moral objections? Me neither.

The agency sees things differently. Employer and insurer obligations, HHS says, are confined to what’s “provided for in comprehensive guidelines,” and the statute doesn’t say what those guidelines should cover. HHS therefore believes that it can exempt whoever it wants, for whatever reason it wants. Just write the exemption into the guidelines.

I don’t think this is a reasonable interpretation of the statute. The guidelines are supposed to elucidate the “additional preventive care and screenings” that must be covered. That’s why Congress enlisted the help of the Health Resources and Services Administration. It’s a health agency, one that “work[s] to improve the health of needy people.” HRSA knows a lot about preventive services and screenings. HRSA isn’t equipped to decide when moral concerns are sufficiently grave as to require an exemption from a generally applicable law.

To sharpen the point, consider the following statute: “All cars must have seatbelts that meet certain specifications, including any additional specifications as provided for in guidelines drafted by the Seatbelt Safety Administration.” If the agency exempted red cars from its guidelines, that wouldn’t be an exercise of its delegated authority to write safety guidelines. It would be revising Congress’s judgment that “[a]ll cars”—red and blue and gray alike—must have safe seatbelts.

That’s what’s happening here. HHS isn’t specifying the services that employers and insurers are obliged to cover. It’s saying that everyone who objects on moral grounds—all those red cars—are exempted. That’s not a plausible interpretation of the statute. Fairly read, it allows HHS to say what gets covered, not who has to cover it.

Yes, it’s true that Congress didn’t prohibit the guidelines from including moral exemptions. But so what? As the D.C. Circuit has said, “the notion that an agency interpretation is permissible just because the statute in question does not expressly negate the existence of a claimed administrative power (i.e. when the statute is not written in ‘thou shalt not’ terms), is both flatly unfaithful to the principles of administrative law. . . and refuted by precedent.”

In a truly baffling legal argument, HHS identifies a long string of statutes that ostensibly “show Congress’ consistent protection of moral convictions alongside religious beliefs in the Federal regulation of health care.” Those statutes, it says, have guided its exercise of discretion to offer a religious exemption from the ACA. HHS then quotes at length from the legislative history of the Church Amendments, which were adopted in 1973. It points out that 45 states have from time to time adopted moral exemptions to statutes. And it invokes “founding principles,” scattering quotations from George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison about liberty of conscience.

How is any of this relevant to the interpretation of the ACA, you might ask? Good question. None of the statutes purport to give HHS the authority to craft a freestanding “moral exemption” from the obligation to cover preventive services for women. To the contrary, the statutes demonstrate that, when Congress wants to add a moral exemption to a statute, it knows how to do so. Far from supporting HHS’s action, all of these statutes undermine it.

The right question, instead, is whether the statute can reasonably be read to have delegated to a health agency the freewheeling power to relieve entities of their responsibility to follow the law. And I don’t see it.

What Happens Now?

I expect that a bunch of advocacy organizations will immediately file suit to challenge the new rules. They’ll ask for an initial stay and then a preliminary injunction, preferably on a nationwide basis. I bet they’ll get it: Texas secured an injunction to stop the Obama administration from implementing DACA without going through notice and comment, and some judge in California or Hawaii will probably enter an injunction on the same theory here.

Yes, the organizations will have to find plaintiffs with standing. But that shouldn’t be hard, at least for the rule governing religious accommodations: there are lots of employers who’d like to limit access to contraception without informing the federal government. Finding a plaintiff for the rule governing moral exemptions might be more difficult, at least initially. HHS thinks that the effect of the rule will be “small,” and that fewer than 10 employers will take advantage of the moral exemption. Maybe that’s right, maybe it’s not—HHS has no way of knowing. But the uncertainty could make it hard to find a viable plaintiff right out of the gate.

Regardless, we’ve got a puzzle on our hands. Why did the Trump administration expose its rules to an obvious legal challenge, one that the challengers are quite likely to win? Conducting notice and comment would take time, but it’s not that hard.

Here’s my working theory: I think the Trump administration wants to signal to evangelicals and Catholics that it really, really cares about religious liberty and understands the importance of curtailing reproductive rights. Refusing to adhere to procedural niceties is one way of signaling that commitment: “We care so much we’ll even ignore the law.” Plus, if the courts enjoin the rules, that’ll play right into existing storylines about how mainline culture sidelines the Christian faith.

In the meantime, HHS is conducting after-the-fact notice and comment on the new rules—the comment period will close on December 5. Although the law on whether after-the-fact notice and comment can cure a “good cause” violation is a bit unsettled—Kristin Hickman and Mark Thomson have a good paper on the question, and I offer some views here—there’s a good chance that the basis for any initial injunction will evaporate. If that happens, the administration will (eventually) gets its rules, while sending a costly signal about the depth of its commitment.

Or maybe HHS is being foolish. I can’t rule that out. But the better explanation, I think, is that the administration is dead serious about curtailing access to contraception, whatever flaws these particular rules may have.

October 4, 2017

What Makes Singapore’s Health Care So Cheap?

The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2017, The New York Times Company) and is jointly authored by Aaron Carroll and Austin Frakt.

Singapore’s health care system is distinctive, and not just because of the improbability that it’s admired by many on both the American left and the right.

It spends less of its economy on health care than any country that was included in our recent tournament on best health systems in the world.

And it spends far, far less than the United States does. Yet it achieves some outcomes Americans would find remarkable. Life expectancy at birth is two to three years longer than in Britain or the United States. Its infant mortality rate is among the lowest in the world, about half that of the United States, and just over half that of Britain, Australia, Canada and France. General mortality rates are impressive compared with pretty much all other countries as well.

When the World Health Organization ranked health care systems in 2000, it placed the United States 37th in quality; Singapore ranked sixth.

Americans tend to think that they have a highly privatized health system, but Singapore is arguably much more so. There, about two-thirds of health care spending is private, and about one-third is public. It’s just about the opposite in the United States.

Singapore’s health system also has a mix of public and private health care delivery organizations. There are private and public hospitals, as well as a number of tiers of care. There are five classes: A, B1, B2+, B2 and C. “A” gets you a private room, your own bathroom, air-conditioning and your choice of doctor. “C” gets you an open ward with seven or eight other patients, a shared bathroom and whatever doctor is assigned to you.

But choosing “A” means you pay for it all. Choosing “C” means the government pays up to 80 percent of the costs.

What also sets Singapore apart, and what makes it beloved among many conservative policy analysts, is its reliance on health savings accounts. All workers are mandated to put a decent percentage of their earnings into savings for the future. Workers up to age 55 have to put 20 percent of their wages into these accounts, matched by an additional 17 percent of wages from their employer. After age 55, these percentages go down.

The money is divided among three types of accounts. There’s an Ordinary Account, to be used for housing, insurance against death and disability, or for investment or education. There’s a Special Account, for old age and investment in retirement-related financial products. And there’s a Medisave Account, to be used for health care expenses and approved medical insurance.

The contribution to Medisave is about 8 percent to 10.5 percent of wages, depending on your age. It earns interest, set by the government. And it has a maximum cap, around $52,000, at which point you’d divert the mandatory savings into some other account.

A second health care program is Medishield Life. This is for catastrophic illness, and while it’s not mandatory, almost all of the population is covered by it. It’s really cheap, from $16 a month for a 29-year-old in 2019 to $68 a month for a 69-year-old, without subsidies.

Medishield Life kicks in when you’ve paid the deductibles for the year, and after you’ve paid your coinsurance. Deductibles vary by your age and the class of care you choose, and range from $1,500 to $3,000. Coinsuranceranges from 3 percent to 20 percent, varying by the size of the medical bill. Medishield Life has an annual limit of $100,000 but no lifetime limit.

Medishield Life is managed so that it covers most of a hospitalization in a Class B2 or C ward. Patients would cover the rest out of their Medisave accounts. Patients also have the option to pay for additional insurance, which would cover a higher class of care. Some plans are offered by the government, and people can use Medisave money to pay for those. Other plans are purely private, and sometimes offered by employers as benefits.

A third health care program is Medifund, which is Singapore’s safety net program. Only citizens are eligible; it covers only the lowest class of wards; and it’s available only after people have depleted their Medisave account and Medishield Life coverage. The amount of help someone could get from Medifund depends on a patient’s and family’s income, condition, expenses and social circumstances. Decisions are made at a very local level.

A number of people hold up Singapore as an example of how conservative ideas of competition and consumer-directed spending work. Unfortunately, the story isn’t so clean when you look at the data. In a 1995 paper in Health Affairs, William Hsiao looked at how health spending fared in Singapore before and after the introduction of Medisave. He found that health care spending increased after the introduction of increased cost-sharing, which is not what most proponents of such changes would expect. Michael Barr had similar thoughts in his “critical inquiry” into Singapore’s medical savings account, published in The Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law in 2001.

But why is Singapore so cheap? Some think that it’s the strong use of health savings accounts and cost-sharing. People who have to use their own money usually spend less. But that’s not the whole story here. There’s a lot of government regulation as well.

Through the tiered care system and its public hospitals, the government has a great deal of control over inpatient care. It allows a private system to challenge the public one, but the public system plays the dominant role in providing services.

Initially, Singapore let hospitals compete more, believing that the free market would bring down costs. But when hospitals competed, they did so by buying new technology, offering expensive services, paying more for doctors, decreasing services to lower-class wards, and focusing more on A-class wards. This led to increased spending.

In other words, Singapore discovered that, as we’ve seen many times before, the market sometimes fails in health care. When that happened in Singapore, government officials got more involved. They established the proportion of each type of ward hospitals had to provide, they kept them from focusing too much on profits, and they required approval to buy new, expensive technology.

Singapore heavily regulates the number of physicians, and it has some control over salaries as well. The country uses bulk purchasing power to spend less on drugs.

The most frustrating part about Singapore is that, as an example, it’s easily misused by those who want to see their own health care systems change. Conservatives will point to the Medisave accounts and the emphasis on individual contributions, but ignore the heavy government involvement and regulation. Liberals will point to the public’s ability to hold down costs and achieve quality, but ignore the class system or the system’s reliance on individual decision-making.

Singapore is also very small, and the population may be healthier in general than in some other countries. It’s a little easier to run a health care system like that. It also makes the system easier to change. We should also note that some question the outcomes on quality, or feel that the government isn’t as honest about the system’s functioning.

There is a big doctor shortage, as well as a shortage of hospital beds. As Mr. Barr noted in a longer discussion of Singapore’s system, “It seems to be highly likely that if one could examine the Singapore health system from the inside, one would find a fairly ordinary health system with some strong points and many weaknesses — much like health systems all over the developed world.” This concern about how much we can really know about Singapore’s true outcomes is one of the reasons it didn’t fare so well in our contest.

October 3, 2017

Healthcare Triage: The Bad Food Bible

Some of our most popular HCT episodes have been about food. Or, rather, they’ve been about the science and research behind food, and the recommendations groups make about what you should, or shouldn’t eat. Good news! I’ve got a book on that topic coming out November 7. It’s called The Bad Food Bible: How and Why to Eat Sinfully. You can preorder it right now, and it’s also the topic of this week’s Healthcare Triage.

You can preorder the book at any of the below:

Amazon

Barnes & Noble

Indiebound

iBooks

Kobo

Any local bookstore you might frequent. You can ask for the book by name or ISBN 978-0544952560

It goes without saying that I would love for you to buy it. Preorder it so you are assured to have it on the day of publication!

It’s Not Just Opioids: Increases in Alcohol Use Disorder (with update)

The US has recently experienced a large increase in opioid abuse and overdose deaths. In JAMA Psychiatry, Bridget Grant and her colleagues report that there have been concurrent increases in alcohol consumption, problem drinking, and diagnosable alcohol use disorder (AUD). AUD is defined in terms of a list of symptoms that include problems in functioning, experiences of craving for alcohol, inability to control drinking, and so on.

OBJECTIVE To present nationally representative data on changes in the prevalences of 12-month alcohol use, 12-month high-risk drinking, 12-month DSM-IV AUD, 12-month DSM-IV AUD among 12-month alcohol users, and 12-month DSM-IV AUD among 12-month high-risk drinkers between 2001-2002 and 2012-2013.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS The study data were derived from face-to-face interviews conducted in 2 nationally representative surveys of US adults: the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, with data collected from April 2001 to June 2002, and the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III, with data collected from April 2012 to June 2013. Data were analyzed in November and December 2016.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES Twelve-month alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and DSM-IV AUD [ = Alcohol Use Disorder].

RESULTS The study sample included 43093 participants in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions and 36 309 participants in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. Between 2001-2002 and 2012-2013, 12-month alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and DSM-IV AUD increased by 11.2%, 29.9%, and 49.4%, respectively, with alcohol use increasing from 65.4% (95% CI, 64.3%-66.6%) to 72.7% (95% CI, 71.4%-73.9%), high-risk drinking increasing from 9.7% (95% CI, 9.3%-10.2%) to 12.6% (95% CI, 12.0%-13.2%), and DSM-IV AUD increasing from 8.5% (95% CI, 8.0%-8.9%) to 12.7% (95% CI, 12.1%-13.3%). With few exceptions, increases in alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and DSM-IV AUD between 2001-2002 and 2012-2013 were also statistically significant across sociodemographic subgroups. Increases in all of these outcomes were greatest among women, older adults, racial/ethnic minorities, and individuals with lower educational level and family income. Increases were also seen for the total sample and most sociodemographic subgroups for the prevalences of 12-month DSM-IV AUD among 12-month alcohol users from 12.9% (95% CI, 12.3%-17.5%) to 17.5% (95% CI, 16.7%-18.3%) and 12-month DSM-IV AUD among 12-month high-risk drinkers from 46.5% (95% CI, 44.3%-48.7%) to 54.5% (95% CI, 52.7%-56.4%).

Here’s the increase in the estimated rates of AUD.

Data from Grant et al., 2007.

Notice that rates of AUD among women have nearly doubled.

What are the consequences of AUD? Problem drinking contributes to mental and behavioural disorders, liver cirrhosis, and some cancers and cardiovascular diseases. It leads to death and injuries resulting from violence and moving vehicle accidents. Using data from the Global Burden of Disease study, Jurgen Rehm and colleagues estimate that

3·8% of all global deaths and 4·6% of global disability-adjusted life-years [are] attributable to alcohol. Disease burden is closely related to average volume of alcohol consumption, and, for every unit of exposure, is strongest in poor people and in those who are marginalised from society.

Opiate overdoses kill you quickly, so a large increase in non-medical usage will cause a rapid increase in deaths. The harms associated with AUD accumulate slowly, like those of smoking. This means that much of the morbidity, mortality, and excess health care costs of current drinking won’t be seen for a few years.

It’s important that the researchers did not actually observe people consuming alcohol, nor did they measure alcohol levels in the bloodstream. Because alcohol use was self-reported, it’s possible that the reported increase stems from a change in people’s willingness to talk to interviewers about their drinking, rather than a change in drinking per se.*

Let’s suppose that the increase in self-reported AUD is only an increase in the reporting of AUD. Because it’s unlikely that many people would falsely report problem drinking — a highly stigmatized behaviour — that would mean that we are now getting a more accurate estimate of the true extent of the problem. If so, it means that the true rate of AUD is ~9% of Americans aged 18 or older, or roughly 20 million people. This, in turn, is roughly 10 times the number of Americans who use opiates for non-medical purposes. This is a frightening number, even if the prevalence hasn’t changed.

Conversely, if AUD is truly increasing, in parallel to the increase in opiate abuse, and we don’t effectively counter it, then the recent decline in American public health will continue.

*Update: German Lopez notes that there are serious criticisms of the methodology of Grant’s study. If you are interested in this topic, read his article. The key criticism is that the methodology of the underlying survey may have changed from one wave to the next. If so, we can’t be sure whether the reported change in AUD is an actual change in the prevalence vs a change in how it’s measured by the survey.

I strongly agree with German’s conclusion:

Between 2001 and 2015, the number of alcohol-induced deaths (those that involve direct health complications from alcohol, like liver cirrhosis) rose from about 20,000 to more than 33,000. Before the latest increases, an analysis of data from 2006 to 2010 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) already estimated that alcohol is linked to 88,000 deaths a year — more than all drug overdose deaths combined.

And another study found that rates of heavy drinking and binge drinking increased in most US counties from 2005 to 2012, even as the percentage of people who drink any alcohol has remained relatively flat.

But for now, it’s hard to say if a massive increase in alcohol use disorder is behind the negative trends — because the evidence for that just isn’t reliable.

September 29, 2017

The Medicaid expansion is associated with fewer diabetes-related hospitalizations in some states

One of the great parts of working at IUSM is getting to interact with some of the amazing researchers at other IU schools, like the School of Public and Environmental Affairs (SPEA). Some of us just published a paper together, “Changes in inpatient payer-mix and hospitalizations following Medicaid expansion: Evidence from all-capture hospital discharge data“:

Context: The Affordable Care Act resulted in unprecedented reductions in the uninsured population through subsidized private insurance and an expansion of Medicaid. Early estimates from the beginning of 2014 showed that the Medicaid expansion decreased uninsured discharges and increased Medicaid discharges with no change in total discharges.

Objective: To provide new estimates of the effect of the ACA on discharges for specific conditions.

Design, setting, and participants: We compared outcomes between states that did and did not expand Medicaid using state-level all-capture discharge data from 2009–2014 for 42 states from the Healthcare Costs and Utilization Project’s FastStats database; for a subset of states we used data through 2015. We stratified the analysis by baseline uninsured rates and used difference-in-differences and synthetic control methods to select comparison states with similar baseline characteristics that did not expand Medicaid.

Main outcome: Our main outcomes were total and condition-specific hospital discharges per 1,000 population and the share of total discharges by payer. Conditions reported separately in FastStats included maternal, surgical, mental health, injury, and diabetes.

Past analyses have shown that the Medicaid expansion was associated with decreases in hospital stays that were uninsured and increases in hospital stays covered by Medicaid, without any real changes in total hospitalizations. That’s somewhat intuitive, but it’s good to know there’s proof. We wanted to see if the Medicaid expansion had any effect on hospitalizations for specific conditions.

We used the Healthcare Costs and Utilization Project’s FastStats database from 2009-2014 (sometimes 2015) to compare states that did and didn’t expand Medicaid. We were interested in the total and condition-specific hospital stays and the share of such stays by insurance coverage. Specifically, we were interested in births, surgeries, mental health stays, injuries, and diabetes. We stratified these analyses by baseline uninsured rates, because it may be that states that started with more uninsured might see more of an effect.

We found that, as other studies have, that uninsured stays fell in the states that expanded Medicaid that had low uninsured rates beforehand (absolute drop of 4.4%) and those that had high uninsured rates beforehand (absolute drop 7.7%). Medicaid covered stays also went up in both types of states (6.4% and 10.5% respectively). The total number of stays didn’t change, nor did the condition-specific stays for most issues.

However, with respect to diabetes, they did. Hospitalizations for diabetes with a high level of uninsurance beforehand fell 0.4% in states that expanded Medicaid. We had some thoughts on why this might be the case:

This result is surprising because individuals with diabetes were more likely to have insurance than those without diabetes before the ACA. However, diabetes has increased significantly among low-income populations over the last several decades, and today half of all uninsured adults with diabetes have incomes low enough to qualify for Medicaid under the ACA. Indeed, recent work demonstrates that adults were more likely to have been diagnosed with diabetes in Medicaid expansion states after the Medicaid expansion and that prescriptions for diabetes management increased the most, of all medication categories, under Medicaid after 2014 in expansion states. If the Medicaid expansion resulted in better access to care for undiagnosed patients with diabetes, then it is possible that hospital utilization could change as well. Many of those newly eligible for Medicaid under the ACA were offered Medicaid managed care, which may better coordinate care of beneficiaries and thus result in avoided hospitalizations.

You may argue that a 0.4% change is small. But we did some back-of-the-envelope calculations using data from HCUP. In 2008, the average cost of a diabetes-related hospital stay was over $12,500 in 2017 dollars. Given our results, a rough estimate of the possible reduction in inpatient diabetes care might be $478 per 1000 population in states that had a high level of uninsurance before the expansion, like Arizona. Therefore, since Arizona had just under 7 million citizens in 2016, the expansion might have saved them about $3.3 million in diabetes-related inpatient stays.

All studies have limitations that warrant consideration, of course, and this study – like all studies – needs replication and further examination. But understanding how the ACA has affected total hospitalizations, by specific type and the payer composition facing hospitals, is especially important as policymakers consider changes to the law.

Go read the whole thing. It’s open access!

Why can’t we do more about suicide?

The child of a friend took his own life. I do not think my friend has stopped weeping since it happened. I’ll be an epidemiologist for a moment, then allow me to ventilate some grief.

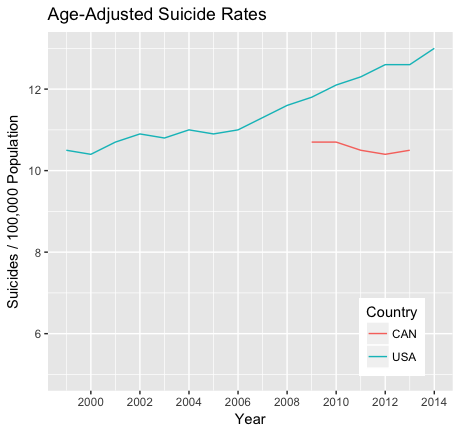

Here’s the recent history of deaths by suicide in the US and Canada.*

Rates from the US National Vital Statistics System and from Statistics Canada.

Age-adjusted deaths by suicide in the US have risen steadily from 1999 to 2014, with an increase of 21% over the period. There were roughly 43,000 suicides in 2014, so there would have been perhaps 7,000 fewer deaths had US rates not risen. This is one of the statistics that led Anne Case and Angus Deaton to raise alarms about increases in “deaths of despair” in the United States. Suicides do not seem to have increased in Canada, but I could only find recent data.

But you know what? Just today I am not worried about the increase. The US rate in 1999 and the Canadian rate today were already much higher than they should be. Why do we ever lose someone in their 20s? I’m furious, with my profession most of all, that we haven’t come up with or disseminated more effective ways to prevent suicides.

*Yes, I truncated the Y-axis at 5 instead of 0 to make the US increase more visually dramatic. Fucking sue me.

September 28, 2017

Faux Federalism

The following is an op-ed that I was shopping around for publication prior to the demise of Graham-Cassidy. It’s obviously less urgent now, but I wanted to put it out there as a time-capsule in case the bill is revived. The op-ed relates to the penultimate version of the bill, not the one that finally died this week.

In defending the Republicans’ latest and most radical effort to undo the Affordable Care Act, Lindsey Graham has said that the “choice for Americans” is “socialism or federalism.” Graham says he prefers federalism: a solution that shifts power away from Washington and back to the states.

There’s merit to the idea. Red states and blue states have different ideas about health reform. Why not give them the freedom to go their own way? Oregon, for example, might let people buy into the Medicaid program, which today covers only the poorest Americans. Kansas might set up an insurance program to cover its sickest residents in an effort to keep premiums lower for everyone else.

Health-care systems would vary from state to state, but that’s the point of federalism. What suits Michigan won’t suit Ohio, and they should each have the room to select their preferred approach unless there’s a good reason for national action. That’s true even when—indeed, especially when—clashing ideological views make it hard to find any kind of common ground.

There are other advantages. States can monitor local conditions and make fine-grained adjustments in their approaches more nimbly and effectively than distant regulators in Washington. And experimentation at the state level allows states to learn from one another about the approaches that work best.

But if you like federalism, you should fear Graham-Cassidy. Far from empowering states, it will assign them tasks they cannot perform; it likely won’t give them needed regulatory flexibility they need; and it will force them to pick which of their residents will have to lose insurance.

Indeed, all the talk about states’ rights masks what’s really at stake in the battle over health reform: does everyone deserve health insurance, the rich and poor alike? Graham-Cassidy offers a decisive answer to that question: no.

Here’s why. Graham-Cassidy would dismantle Obamacare, ending the expansion of Medicaid coverage to the poor as well as the subsidies that people use to buy private coverage. HealthCare.gov would go up in smoke, as would the individual mandate, the employer mandate, and a bunch of other taxes used to finance coverage.

In its place, Graham-Cassidy would offer block grants to the states. Those block grants aren’t nearly large enough to cover the lost Obamacare money: by one estimate, it will cut $243 billion over a seven-year period from the current baseline.

States that have worked hardest to cover the uninsured (like California) are penalized the most. States that have sabotaged Obamacare at every turn (like Texas) fare much better. But every dollar cut from the bill will mean one fewer dollar for insurance. Tens of millions of people will lose coverage.

The states could try to make up for the shortfall themselves, but they generally won’t have the fiscal capacity to do so. In contrast to the federal government, all the states (save Vermont) have to balance their budgets every year. When the next recession comes around, the ranks of the uninsured will swell at precisely the moment that state tax revenues take a nosedive. To keep covering the uninsured, states will have to either raise taxes or cut funding—which will only exacerbate the recession. This “countercyclical trap” makes states nervous about committing to cover the uninsured.

Federal money is the lifeblood of health reform because the states need to leverage the federal government’s ability to run a deficit in tough times. With the big Graham-Cassidy cuts, states will only have the flexibility to make really unpopular choices about who loses health coverage. What kind of federalism is that?

That’s if all goes well—and it won’t all go well. Under Graham-Cassidy, states are expected to establish the laws, policies, and infrastructure necessary to spend billions of dollars in infrastructure by 2020. That’s not enough time to navigate tricky state politics and hire hundreds of people with expertise in the complexities of Medicaid administration and insurance regulation. The likely result will be infighting, confusion, and chaos.

That’s especially so since the funding for Graham-Cassidy runs out in 2026. States are therefore being asked to reform their entire health-care systems around block grants that may abruptly terminate. The long-run uncertainty will make it that much harder for states to invest today in remaking their health-care markets.

It gets worse. In its current form, Graham-Cassidy allows states to opt out of Obamacare regulations. The waivers are broad: states could, for example, be exempted from the rule requiring insurers to cover the essential health benefits. Waivers would also allow insurers to charge sick people more for their health coverage, and to place annual or lifetime caps on their benefits.

But these waivers aren’t likely to make it into the final bill. To avoid the filibuster, Republicans are trying to pass Graham-Cassidy through the budget reconciliation process. By law, however, reconciliation bills can only contain provisions that affect spending or revenue. Provisions that are “merely incidental” to the bill’s budget effects can be stripped out by a Senate official known as the Parliamentarian.

The Parliamentarian hasn’t yet ruled on whether the waiver provision passes muster. On an earlier repeal bill, however, she said that Republicans couldn’t include a similarly expansive waiver provision: it was “merely incidental” to the budget. The Graham-Cassidy waivers have been drafted to dodge the problem, but the dodge is transparent. In all likelihood, the waiver provision will be struck.

The uncertainty over waivers means that Republicans don’t yet know what they’ll be voting on, even though a September 30 deadline for passing Graham-Cassidy through reconciliation is only a week away. They might not know until a few days—hours, even—before the vote is scheduled. And they may be voting on a bill that doesn’t afford states the flexibility that Republicans have promised them.

That’s no way to reshape one-sixth of the American economy. And it’s no way to honor the principles of federalism that appear in Republican talking points. Graham-Cassidy should be seen for what it is: an effort to prevent any level of government, state or federal, from making good on the promise of universal coverage.

Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers