Andrew Huang's Blog, page 12

February 28, 2022

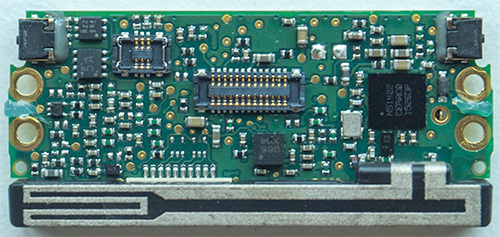

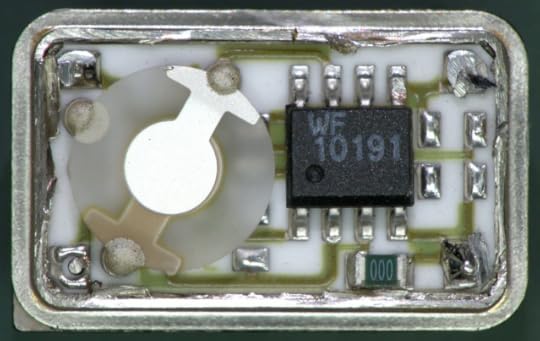

Name that Ware, February 2022

The Ware for February 2022 is shown below.

I was cleaning out my desk and decided to give this a crack and see what was inside. There’s a couple things I found notable about the design. First, basically every part on the inside is a catalog part or an OEM variant of one — I’m used to opening up these types of devices and seeing more full custom ASICs, weirdo unsearchable Japanese or Chinese part numbers, or anonymous black globs of glue. It’s kind of neat that catalog parts have caught up to the point where you could build one of these essentially just ordering stuff off of Digi-Key (alternatively, one could lament that it’s sad that “Moore’s Law” (in the broader sense) has slowed to the point where it’s no longer economically viable to spin custom ASICs even for products like this). Second, I really liked the antenna. It’s making good use of all three spatial dimensions, yet the design is clean and simple. It is a little bit odd, though, that no underfill was used to secure any of the chips, but maybe that’s part of the reason why it’s in my scrap pile.

Winner, Name that Ware January 2022

The Ware for January 2022 was a Cisco Small Business Unified Communications UC540W-FXO-K9 VoIP gateway. Thanks again to jackw01 for contributing this ware! As for the winner, Ryan nailed the model number so he wins the prize (congrats and please email me!), but I have to mention I found GotNoTime’s comment about Cisco’s love affair with SMART memory interesting and informative. Thanks for playing!

February 16, 2022

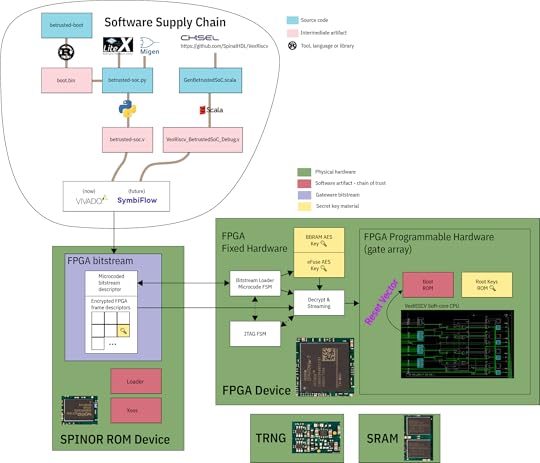

Precursor: From Boot to Root

I have always wanted a computer that was open enough that it can be inspected for security, and also simple enough that I could analyze it in practice. Precursor is a step towards that goal.

As a test, I made a one hour video that walks through the Precursor tech stack, from hardware to root keys. I feel it’s a nice demo of what evidence-based trust should look like:

The video is a bit of a firehose, so please refer to our wiki for more info, or open an issue to further the discussion.

February 8, 2022

The Plausibly Deniable DataBase (PDDB)

The problem with building a device that is good at keeping secrets is that it turns users into the weakest link.

From xkcd, CC-BY-NC 2.5

In practice, attackers need not go nearly as far as rubber-hose cryptanalysis to obtain passwords; a simple inspection checkpoint, verbal threat or subpoena is often sufficiently coercive.

Most security schemes facilitate the coercive processes of an attacker because they disclose metadata about the secret data, such as the name and size of encrypted files. This allows specific and enforceable demands to be made: “Give us the passwords for these three encrypted files with names A, B and C, or else…”. In other words, security often focuses on protecting the confidentiality of data, but lacks deniability.

A scheme with deniability would make even the existence of secret files difficult to prove. This makes it difficult for an attacker to formulate a coherent demand: “There’s no evidence of undisclosed data. Should we even bother to make threats?” A lack of evidence makes it more difficult to make specific and enforceable demands.

Thus, assuming the ultimate goal of security is to protect the safety of users as human beings, and not just their files, enhanced security should come hand-in-hand with enhanced plausible deniability (PD). PD arms users with a set of tools they can use to navigate the social landscape of security, by making it difficult to enumerate all the secrets potentially contained within a device, even with deep forensic analysis.

Precursor is a device we designed to keep secrets, such as passwords, wallets, authentication tokens, contacts and text messages. We also want it to offer plausible deniability in the face of an attacker that has unlimited access to a physical device, including its root keys, and a set of “broadly known to exist” passwords, such as the screen unlock password and the update signing password. We further assume that an attacker can take a full, low-level snapshot of the entire contents of the FLASH memory, including memory marked as reserved or erased. Finally, we assume that a device, in the worst case, may be subject to repeated, intrusive inspections of this nature.

We created the PDDB (Plausibly Deniable DataBase) to address this threat scenario. The PDDB aims to offer users a real option to plausibly deny the existence of secret data on a Precursor device. This option is strongest in the case of a single inspection. If a device is expected to withstand repeated inspections by the same attacker, then the user has to make a choice between performance and deniability. A “small” set of secrets (relative to the entire disk size, on Precursor that would be 8MiB out of 100MiB total size) can be deniable without a performance impact, but if larger (e.g. 80MiB out of 100MiB total size) sets of secrets must be kept, then archived data needs to be turned over frequently, to foil ciphertext comparison attacks between disk imaging events.

The API Problem

“Never roll your own crypto”, and “never roll your own filesystem”: two timeless pieces of advice worth heeding. Yet, the PDDB is both a bit of new crypto, and a lot of new filesystem (and I’m not particularly qualified to write either). So, why take on the endeavor, especially when deniability is not a new concept?

For example, one can fill a disk with random data, and then use a Veracrypt hidden volume, or LUKS with detached partition headers. So long as the entire disk is pre-filled with random data, it is difficult for an attacker to prove the existence of a hidden volume with these pre-existing technologies.

Volume-based schemes like these suffer from what I call the “API Problem”. While the volume itself may be deniable, it requires application programs to be PD-aware to avoid accidental disclosures. For example, they must be specifically coded to split user data into multiple secret volumes, and to not throw errors when the secret volumes are taken off-line. This substantially increases the risk of unintentional leakage; for example, an application that is PD-naive could very reasonably throw an error message informing the user (and thus potentially an attacker) of a supposedly non-existent volume that was taken off-line. In other words, having the filesystem itself disappear is not enough; all the user-level applications should be coded in a PD-aware fashion.

On the other hand, application developers are typically not experts in cryptography or security, and they might reasonably expect the OS to handle tricky things like PD. Thus, in order to reduce the burden on application developers, the PDDB is structured not as a traditional filesystem, but as a single database of dictionaries containing many key-value pairs.

Secrets are overlaid or removed from the database transparently, through a mechanism called “Bases” (the plural of a single “Basis”, similar to the concept of a vector basis from linear algebra). The application-facing view of data is computed as the union of the key/value pairs within the currently unlocked secret Bases. In the case that the same key exists within dictionaries with the same name in more than one Basis, by default the most recently unlocked key/value pairs take precedence over the oldest. By offering multiple views of the same dataset based on the currently unlocked set of secrets, application developers don’t have to do anything special to leverage the PD aspects of the PDDB.

The role of a Basis in PD is perhaps best demonstrated through a thought experiment centered around the implementation of a chat application. In Precursor, the oldest (first to be unlocked) Basis is always the “System” Basis, which is unlocked on boot by the user unlock password. Now let’s say the chat application has a “contact book”. Let’s suppose the contact book is implemented as a dictionary called “chat.contacts”, and it exists in the (default) System Basis. Now let’s suppose the user adds two contacts to their contact book, Alice and Bob. The contact information for both will be stored as key/value pairs within the “chat.contacts” dictionary, inside the System Basis.

Now, let’s say the user wants to add a new, secret contact for Trent. The user would first create a new Basis for Trent – let’s say it’s called “Trent’s Basis”. The chat application would store the new contact information in the same old dictionary called “chat.contacts”, but the PDDB writes the contact information to a key/value pair in a second copy of the “chat.contacts” dictionary within “Trent’s Basis”.

Once the chat with Trent is finished, the user can lock Trent’s Basis (it would also be best practice to refresh the chat application). This causes the key/value pair for Trent to disappear from the unionized view of “chat.contacts” – only Alice and Bob’s contacts remain. Significantly, the “chat.contacts” dictionary did not disappear – the application can continue to use the same dictionary, but future queries of the dictionary to generate a listing of available contacts will return only Alice and Bob’s key/value pairs; Trent’s key/value pair will remain hidden until Trent’s Basis is unlocked again.

Of course, nothing prevents a chat application from going out of its way to maintain a separate copy of the contact book, thus allowing it to leak the existence of Trent’s key/value pair after the secret Basis is closed. However, that is extra work on behalf of the application developer. The idea behind the PDDB is to make the lowest-effort method also the safest method. Keeping a local copy of the contacts directory takes effort, versus simply calling the dict_list() API on the PDDB to extract the contact list on the fly. However, the PDDB API also includes a provision for a callback, attached to every key, that can inform applications when a particular key has been subtracted from the current view of data due to a secret Basis being locked.

Contrast this to any implementation using e.g. a separate encrypted volume for PD. Every chat application author would have to include special-case code to check for the presence of the deniable volumes, and to unionize the contact book. Furthermore, the responsibility to not leak un-deniable references to deniable volumes inside the chat applications falls squarely on the shoulders of each and every application developer.

In short, by pushing the deniability problem up the filesystem stack to the application level, one greatly increases the chances of accidental disclosure of deniable data. Thus a key motivation for building the PDDB is to provide a set of abstractions that lower the effort for application developers to take advantage of PD, while reducing the surface of issues to audit for the potential leakage of deniable data.

Down the Rabbit Hole: The PDDB’s Internal Layout

Since we’re taking a clean-sheet look at building an encrypted, plausibly-deniable filesystem, I decided to start by completely abandoning any legacy notion of disks and volumes. In the case of the PDDB, the entire “disk” is memory-mapped into the virtual memory space of the processor, on 4k-page boundaries. Like the operating system Xous, the entire PDDB is coded to port seamlessly between both 32-bit and 64-bit architectures. Thus, on a 32-bit machine, the maximum size of the PDDB is limited to a couple GiB (since it has to share memory space with the OS), but on a 64-bit machine the maximum size is some millions of terabytes. While a couple GiB is small by today’s standards, it is ample for Precursor because our firmware blob-free, directly-managed, high write-lifetime FLASH memory device is only 128MiB in size.

Each Basis in the PDDB has its own private 64-bit memory space, which are multiplexed into physical memory through the page table. It is conceptually similar to the page table used to manage the main memory on the CPU: each physical page of storage maps to a page table entry by shifting its address to the right by 12 bits (the address width of a 4k page). Thus, Precursor’s roughly 100MiB of available FLASH memory maps to about 25,000 entries. These entries are stored sequentially at the beginning of the PDDB physical memory space.

Unlike a standard page table, each entry is 128 bits wide. An entry width of 128 bits allows each page table entry to be decrypted and encrypted independently with AES-256 (recall that even though the key size is 256 bits, the block size remains at 128 bits). 56 bits of the 128 bits in the page table entry are used to encode the corresponding virtual address of the entry, and the rest are used to store flags, a nonce and a checksum. When a Basis is unlocked, each of the 25,000 page table entries are scanned by decrypting them using the unlock key for candidates that have a matching checksum; all the candidates are stored in a hash table in RAM for later reference. We call them “entry candidates” because the checksum is too small to be cryptographically secure; however, the actual page data itself is protected using AES-GCM-SIV, which provides cryptographically strong authentication in addition to confidentiality.

Fortunately, our CPU, like most other modern CPUs, support accelerated AES instructions, so scanning 25k AES blocks for valid pages does not take a long time, just a couple of seconds.

To recap, every time a Basis is unlocked, the page table is scanned for entries that decrypt correctly. Thus, each Basis has its own private 64-bit memory space, multiplexed into physical memory via the page table, allowing us to have multiple, concurrent cryptographic Bases.

Since every Basis is orthogonal, every Basis can have the exact same virtual memory layout, as shown below. The layout always uses 64-bit addressing, even on 32-bit machines.

| Start Address | ||------------------------|-------------------------------------------|| 0x0000_0000_0000_0000 | Invalid -- VPAGE 0 reserved for Option || 0x0000_0000_0000_0FE0 | Basis root page || 0x0000_0000_00FE_0000 | Dictionary[0] || +0 | - Dict header (127 bytes) || +7F | - Maybe key entry (127 bytes) || +FE | - Maybe key entry (127 bytes) || +FD_FF02 | - Last key entry start (128k possible) || 0x0000_0000_01FC_0000 | Dictionary[1] || 0x0000_003F_7F02_0000 | Dictionary[16382] || 0x0000_003F_8000_0000 | Small data pool start (~256GiB) || | - Dict[0] pool = 16MiB (4k vpages) || | - SmallPool[0] || +FE0 | - SmallPool[1]| 0x0000_003F_80FE_0000 | - Dict[1] pool = 16MiB || 0x0000_007E_FE04_0000 | - Dict[16383] pool || 0x0000_007E_FF02_0000 | Unused || 0x0000_007F_0000_0000 | Medium data pool start || | - TBD || 0x0000_FE00_0000_0000 | Large data pool start (~16mm TiB) || | - Demand-allocated, bump-pointer || | currently no defrag |The zeroth page is invalid, so we can have “zero-cost” Option abstractions in Rust by using the NonZeroU64 type for Basis virtual addresses. Also note that the size of a virtual page is 0xFE0 (4064) bytes; 32 bytes of overhead on each 4096-byte physical page are consumed by a journal number plus AES-GCM-SIV’s nonce and MAC.

The first page contains the Basis Root Page, which contains the name of the Basis as well as the number of dictionaries contained within the Basis. A Basis can address up to 16,384 dictionaries, and each dictionary can address up to 131,071 keys, for a total of up to 2 billion keys. Each of these keys can map a contiguous blob of data that is limited to 32GiB in size.

The key size cap can be adjusted to a larger size by tweaking a constant in the API file, but it is a trade-off between adequate storage capacity and simplicity of implementation. 32GiB is not big enough for “web-scale” applications, but it’s large enough to hold a typical Blu-Ray movie as a single key, and certainly larger than anything that Precursor can handle in practice with its 32-bit architecture. Then again, nothing about Precursor, or its intended use cases, are web-scale. The advantage of capping key sizes at 32GiB is that we can use a simple “bump allocator” for large data: every new key reserves a fresh block of data in virtual memory space that is 32GiB in size, and deleted keys simply “leak” their discarded space. This means that the PDDB can handle a lifetime total of 200 million unique key allocations before it exhausts the bump allocator’s memory space. Given that the write-cycle lifetime of the FLASH memory itself is only 100k cycles per sector, it’s more likely that the hardware will wear out before we run out of key allocation space.

To further take pressure off the bump allocator, keys that are smaller than one page (4kiB) are merged together and stored in a dedicated “small key” pool. Each dictionary gets a private pool of up to 16MiB storage for small keys before they fall back to the “large key” pool and allocate a 32GiB chunk of space. This allows for the efficient storage of small records, such as system configuration data which can consist of hundreds of keys, each containing just a few dozen bytes of data. The “small key” pool has an allocator that will re-use pages as they become free, so there is no lifetime limit on unique allocations. Thus the 200-million unique key lifetime allocation limit only applies to keys that are larger than 4kiB. We refer readers to YiFang Wang’s master thesis for an in-depth discussion of the statistics of file size, usage and count.

Keeping Secret Bases Secret

As mentioned previously, most security protocols do a good job of protecting confidentiality, but do little to hide metadata. For example, user-based password authentication protocols can do a good job of keeping the password a secret, but the existence of a user is plain to see, since the username, salt, and password hash are recorded in an unencrypted database. Thus, most standard authentication schemes that rely on unique salts would also directly disclose the existence of secret Bases through a side channel consisting of Basis authentication metadata.

Thus, we use a slightly modified key derivation function for secret Bases. The PDDB starts with a per-device unique block of salt that is fixed and common to all Bases on that device. This salt is hashed with the user-provided name of the Basis to generate a per-Basis unique salt, which is then combined with the password using bcrypt to generate a 24-byte password hash. This password is then expanded to 32 bytes using SHA512/256 to generate the final AES-256 key that is used to unlock a Basis.

This scheme has the following important properties:

No metadata to leak about the presence of secret BasesA unique salt per deviceA unique (but predictable given the per-device salt and Basis name) salt per-BasisNo storage of the password or metadata on-deviceNo compromise in the case that the root keys are disclosedNo compromise of other secret Bases if passwords are disclosed for some of the BasesThis scheme does not offer forward secrecy in and of itself, in part because this would increase the wear-load of the FLASH memory and substantially degrade filesystem performance.

Managing Free Space

The amount of free space available on a device is a potent side channel that can disclose the existence of secret data. If a filesystem always faithfully reports the amount of free space available, an attacker can deduce the existence of secret data by simply subtracting the space used by the data decrypted using the disclosed passwords from the total space of the disk, and compare it to the reported free space. If there is less free space reported, one may conclude that additional hidden data exists.

As a result PD is a double-edged sword. Locked, secret Bases must walk and talk exactly like free space. I believe that any effective PD system is fundamentally vulnerable to a loss-of-data attack where an attacker forces the user to download a very large file, filling all the putative “free space” with garbage, resulting in the erasure of any secret Bases. Unfortunately, the best work-around I have for this is to keep backups of your archival data on another Precursor device that is kept in a secure location.

That being said, the requirement for no sidechannel through free space is at direct odds with performance and usability. In the extreme, any time a user wishes to allocate data, they must unlock all the secret Bases so that the true extent of free space can be known, and then the secret Bases are re-locked after the allocation is completed. This scheme would leak no information about the amount of data stored on the device when the Bases are locked.

Of course, this is a bad user experience and utterly unusable. The other extreme is to keep an exact list of the actual free space on the device, which would protect any secret data without having to ever unlock the secrets themselves, but would provide a clear measure of the total amount of secret data on the device.

The PDDB adopts a middle-of-the-road solution, where a small subset of the true free space available on disk is disclosed, and the rest is maybe data, or maybe free space. We call this deliberately disclosed subset of free space the “FastSpace cache”. To be effective, the FastSpace cache is always a much smaller number than the total size of the disk. In the case of Precursor, the total size of the PDDB is 100MiB, and the FastSpace cache records the location of up to 8MiB of free pages.

Thus, if an attacker examines the FastSpace cache and it contains 1MiB of free space, it does not necessarily mean that 99MiB of data must be stored on the device; it could also be that the user has written only 7MiB of data to the device, and in fact the other 93MiB are truly free space, or any number of other scenarios in between.

Of course, whenever the FastSpace cache is exhausted, the user must go through a ritual of unlocking all their secret Bases, otherwise they run the risk of losing data. For a device like Precursor, this shouldn’t happen too frequently because it’s somewhat deliberately not capable of handling rich media types such as photos and videos. We envision Precursor to be used mainly for storing passwords, authentication tokens, wallets, text chat logs and the like. It would take quite a while to fill up the 8MiB FastSpace cache with this type of data. However, if the PDDB were ported to a PC and scaled up to the size of, for example, an entire 500GiB SSD, the FastSpace cache could likewise be grown to dozens of GiB, allowing a user to accumulate a reasonable amount of rich media before having to unlock all Bases and renew their FastSpace cache.

This all works fairly well in the scenario that a Precursor must survive a single point inspection with full PD of secret Bases. In the worst case, the secrets could be deleted by an attacker who fills the free space with random data, but in no case could the attacker prove that secret data existed from forensic examination of the device alone.

This scheme starts to break down in the case that a user may be subject to multiple, repeat examinations that involve a full forensic snapshot of the disk. In this case, the attacker can develop a “diff” profile of sectors that have not changed between each inspection, and compare them against the locations of the disclosed Bases. The remedy to this would be a periodic “scrub” where entries have their AES-GCM-SIV nonce renewed. This actually happens automatically if a record is updated, but for truly read-only archive data its location and nonce would remain fixed on the disk over time. The scrub procedure has not yet been implemented in the current release of the PDDB, but it is a pending feature. The scrub could be fast if the amount of data stored is small, but a re-noncing of the entire disk (including flushing true free space with new tranches of random noise) would be the most robust strategy in the face of an attacker that is known to take repeated forensic snapshots of a user’s device.

Code Location and Wrap-Up

If you want to learn more about the details of the PDDB, I’ve embedded extensive documentation in the source code directly. The API is roughly modeled after Rust’s std::io::File model, where a .get() call is similar to the usual .open() call, and then a handle is returned which uses Read and Write traits for interaction with the key data itself. For a “live” example of its usage, users can have a look at WiFi connection manager, which saves a list of access points and their WPA keys in a dictionary: code for saving an entry, code for accessing entries.

Our CI tests contain examples of more interesting edge cases. We also have the ability to save out a PDDB image in “hosted mode” (that is, with Xous directly running on your local machine) and scrub through its entrails with a Python script that greatly aids with debugging edge cases. The debugging script is only capable of dumping and analyzing a static image of the PDDB, and is coded to “just work well enough” for that job, but is nonetheless a useful resource if you’re looking to go deeper into the rabbit hole.

Please keep in mind that the PDDB is very much in its infancy, so there are likely to be bugs and API-breaking changes down the road. There’s also a lot of work that needs to be done on the UX for the PDDB. At the moment, we only have Rust API calls, so that applications can create and use secret Bases as well as dictionaries and keys. There currently are no user-facing command line tools, or a graphical “File Explorer” style tool available, but we hope to remedy this soon. However, I’m very happy that we were able to complete the core implementation of the PDDB. I’m hopeful that out-of-the-box, application developers for Precursor will start using the PDDB for data storage, so that we can start a community dialogue on the overall design.

This work was funded in part through the NGI0 PET Fund, a fund established by NLNet with financial support from the European Commission’s Next Generation Internet Programme.

January 31, 2022

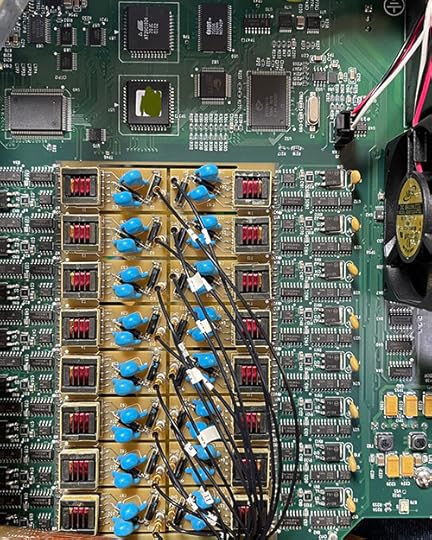

Name that Ware, January 2022

The Ware for January 2022 is shown below.

This is another fine ware contributed by jackw01. I’ve cropped it to hide the connectors, which are a dead give-away, but I figure despite the cropping this has a very good chance of being quickly and exactly guessed. I always find this style of ware entertaining by the still-present debug headers and its top-shelf selection of components.

Winner, Name that Ware December 2021

The Ware for December 2021 was a portion of the main PCB from an Experion Automated Electrophoresis Station. According to Nava (thanks again for the ware!):

So all the high voltage stuff is to drive the electrophoresis, up to 2200V. The idea is rather than running gels this instrument does everything on microfludic chips, these have 16 independent channels, hence the 16 drive voltages.

I’ll give the prize this month to FETguy. I, too, initially thought this was some sort of a piezo driver array, but I did not have the insight to realize that the voltage doublers were incapable of playing that role and ended up chasing a dead end. Thanks for sharing your analysis. Congrats and email me for your prize!

December 28, 2021

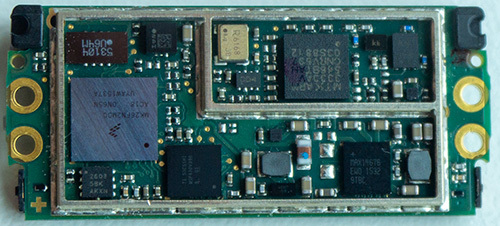

Name that Ware, December 2021

The Ware for December 2021 is shown below:

Thanks to Nava Whiteford for once again contributing another interesting and challenging ware.

Happy holidays to everyone, and may your 2022 be an improvement over 2021!

Winner, Name that Ware November 2021

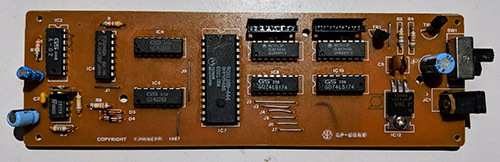

The Ware for November 2021 is the controller PCB from a late ’80s vintage “Caroling Christmas Bells” set. As described by the contributor: “Basically it’s a string of twelve electromagnetically-actuated brass bells that play christmas songs. These seem to have been quite popular at the time as there’s hundreds of sets for sale on eBay right now. It’s pretty cool to see a novelty product like this implemented using discrete logic chips.”

Thanks again to jackw01 for contributing this seasonal ware!

I haven’t seen the ware myself, but I think Adam Robinson’s description is close enough to me to declare it a winner. Congrats, an email me for your prize!

December 13, 2021

Fixing a Tiny Corner of the Supply Chain

No product gets built without at least one good supply chain war story – especially true in these strange times. Before we get into the details of the story, I feel it’s worth understanding a bit more about the part that caused me so much trouble: what it does, and why it’s so special.

The Part that Could Not Be Found

There’s a bit of magic in virtually every piece of modern electronics involved in the generation of internal timing signals. It’s called an oscillator, and typically it’s implemented with a precisely cut fleck of quartz crystal that “rings” when stimulated, vibrating millions of times per second. The accuracy of the crystal is measured in parts-per-million, such that over a month – about 2.5 million seconds – a run-of-the-mill crystal with 50ppm accuracy might drift by about two minutes. In mechanical terms it’s like producing 1kg (2.2 pound) bags of rice that have precisely no more and no less than one grain of rice compared to each other; or in CS terms it’s about 15 bits of precision (it’s funny how one metric sounds hard, while the other sounds trivial).

One of the many problems with quartz crystals is that they are big. Here’s a photo from wikipedia of the inside of a typical oscillator:

CC BY-SA 4.0 by Binarysequence via Wikipedia

The disk on the left is the crystal itself. Because the frequency of the crystal is directly related to its size, there’s a “physics limit” on how small these things can be. Their large size also imposes a limit on how much power it takes to drive them (it’s a lot). As a result, they tend to be large, and power-hungry – it’s not uncommon for a crystal oscillator to be specified to consume a couple milliamperes of current in normal operation (and yes, there are also chips that integrated oscillator circuits that can drive crystals, which reduces power; but they, too, have to burn the energy to charge and discharge some picofarads of capacitance millions of times per second due to the macroscopic nature of the crystal itself).

A company called SiTime has been quietly disrupting the crystal industry by building MEMS-based silicon resonators that can outperform quartz crystals in almost every way. The part I’m using is the SiT8021, and it’s tiny (1.5×0.8mm), surface-mountable (CSBGA), consumes about 100x less power than the quartz-based competition, and has a comparable frequency stability of 100ppm. Remarkably, despite being better in almost every way, it’s also cheaper – if you can get your hands on it. More on that later.

Whenever something like this comes along, I always like to ask “how come this didn’t happen sooner?”. You usually learn something interesting in exploring that question. In the case of pure-silicon oscillators, they have been around forever, but they are extremely sensitive to temperature and aging. Anyone who has designed analog circuits in silicon are familiar with the problem that basically every circuit element is a “temperature-to-X” converter, where X is the parameter you wish you could control. For example, a run of the mill “ring oscillator” with no special compensation would have an initial frequency accuracy of about 50% – going back to our analogies, it’d be like getting a bag of rice that nominally holds 1kg, but is filled to an actual weight of somewhere between 0.5kg and 1.5kg – and you would get swings of an additional 30% depending upon the ambient temperature. A silicon MEMS oscillator is a bit better than that, but its frequency output would still vary wildly with temperature; orders of magnitude more than the parts-per-million specified for a quartz crystal.

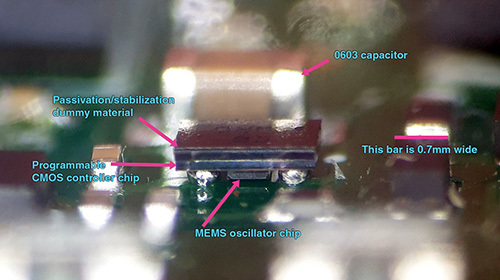

So, how do they turn something so innately terrible into something better-than-quartz? First I took a look at the devices under a microscope, and it’s immediately obvious that it’s actually two chips that have been bonded face-to-face with each other.

Edge-on view of an SiT8021 already mounted on a circuit board.

I deduced that a MEMS oscillator chip is nestled between the balls that bond the chip to the PCB. I did a quick trawl through the patents filed by SiTimes, and I’m guessing the MEMS oscillator chip contains at least two separate oscillators. These oscillators are intentionally different, so that their frequency drift with temperature also have different, but predictable, curves. They can use the relative difference of the frequencies to very precisely measure the absolute temperature of the pair of oscillators by comparing the instantaneous difference between the two frequencies. In other words, they took the exact problem that plagues silicon designs, and turned it into a feature: they built a very precise temperature sensor out of two silicon oscillators.

With the temperature of the oscillators known to exquisite precision, one can now compensate for the temperature effects. That’s what the larger of the two chips (the one directly attached to the solder balls) presumably does. It computes an inverse mapping of temperature vs. frequency, constantly adjusting a PLL driven by one of the two MEMs oscillators, to derive a precise, temperature-stable net frequency. The controller chip presumably also contains a set of eFuses that are burned in the factory (or by the distributor) to calibrate and set the initial frequency of the device. I didn’t do an acid decap of the controller chip, but it’s probably not unreasonable for it to be fabricated in 28nm silicon; at this geometry you could fit an entire RISC-V CPU in there with substantial microcode and effectively “wrap a computer” around the temperature drift problem that plagues silicon designs.

Significantly, the small size of the MEMS resonator compared to a quartz crystal, along with its extremely intimate bonding to the control electronics, means a fundamentally lower limit on the amount of energy required to sustain resonance, which probably goes a long way towards explaining why this circuit is able to reduce active power by so much.

The tiny size of the controller chip means that a typical 300mm wafer will yield about 50,000 chips; going by the “rule of thumb” that a processed wafer is roughly $3k, that puts the price of a raw, untested controller chip at about $0.06. The MEMs device is presumably a bit more expensive, and the bonding process itself can’t be cheap, but at a “street price” of about $0.64 each in 10k quantities, I imagine SiTime is still making good margin. All that being said, a million of these oscillators would fit on about 18 wafers, and the standard “bulk” wafer cassette in a fab holds 25 wafers (and a single fab will pump out about 25,000 – 50,000 wafers a month); so, this is a device that’s clearly ready for mobile-phone scale production.

Despite the production capacity, the unique characteristics of the SiT8021 make it a strong candidate to be designed into mobile phones of all types, so I would likely be competing with companies like Apple and Samsung for my tiny slice of the supply chain.

The Supply Chain War Story

It’s clearly a great part for a low-power mobile device like Precursor, which is why I designed it into the device. Unfortunately, there’s also no real substitute for it. Nobody else makes a MEMS oscillator of comparable quality, and as outlined above, this device is smaller and orders of magnitude lower power than an equivalent quartz crystal. It’s so power-efficient that in many chips it is less power to use this off-chip oscillator, than to use the built-in crystal oscillator to drive a passive crystal. For example, the STM32H7 HSE burns 450uA, whereas the SiT8021 runs at 160uA. To be fair, one also has to drive the pad input capacitance of the STM32, but even with that considered you’re probably around 250uA.

To put it in customer-facing terms, if I were forced to substitute commonly available quartz oscillators for this part, the instant-on standby time of a Precursor device would be cut from a bit over 50 hours down to about 40 hours (standby current would go from 11mA up to 13mA).

If this doesn’t make the part special enough, the fact that it’s an oscillator puts it in a special class with respect to electromagnetic compliance (EMC) regulations. These are the regulations that make sure that radios don’t interfere with each other, and like them or not, countries take them very seriously as trade barriers – by requiring expensive certifications, you’re able to eliminate the competition of small upstarts and cheap import equipment on “radio safety” grounds. Because the quality of radio signals depend directly upon the quality of the oscillator used to derive them, the regulations (quite reasonably) disallow substitutions of oscillators without re-certification. Thus, even if I wanted to take the hit on standby time and substitute the part, I’d have to go through the entire certification process again, at a cost of several thousand dollars and some weeks of additional delay.

Thus this part, along with the FPGA, is probably one of the two parts on the entire BOM that I really could not do without. Of course, I focused a lot on securing the FPGA, because of its high cost and known difficulty to source; but for want of a $0.68 crystal, a $565 product would not be shipped…

The supply chain saga starts when I ordered a couple thousand of these in January 2021, back when it had about a 30 week lead time, giving a delivery sometime in late August 2021. After waiting about 28 weeks, on August 12th, we got an email from our distributor informing us that they had to cancel our entire order for SiT8021s. That’s 28 weeks lost!

The nominal reason given was that the machine used to set the frequency of the chips was broken or otherwise unavailable, and due to supply chain problems it couldn’t be fixed anytime soon. Thus, we had to go to the factory to get the parts. But, in order to order direct from the factory, we had to order 18,000 pieces minimum – over 9x of what I needed. Recall that one wafer yields 58,000 chips, so this isn’t even half a wafer’s worth of oscillators. That being said, 18,000 chips would be about $12,000. This isn’t chump change for a project operating on a fixed budget. It’s expensive enough that I considered recertification of the product to use a different oscillator, if it weren’t for the degradation in standby time.

Panic ensues. We immediately trawl all the white-market distributor channels and buy out all the stock, regardless of the price. Instead of paying our quoted rate of $0.68, we’re paying as much as $1.05 each, but we’re still short about 300 oscillators.

I instruct the buyers to search the gray market channels, and they come back with offers at $5 or $6 for the $0.68 part, with no guarantee of fitness or function. In other words, I could pay 10x of the value of the part and get a box of bricks, and the broker could just disappear into the night with my money.

No deal. I I had to do better.

By this time, every distributor was repeating the “18k Minimum Order Quantity (MOQ) with long lead time” offer, and my buyers in China waved the white flag and asked me to intervene. After trawling the Internet for a couple hours, I discover that Element14 right here in Singapore (where I live) claims to be able to deliver small quantities of the oscillator before the end of the year. It seems too good to be true.

I ask my buyers in China to place an order, and they balk; the China office repeats that there is simply no stock. This has happened before, due to trade restrictions and regional differences the inventory in one region may not be orderable in another, so I agree to order the balance of the oscillators with a personal credit card, and consign them directly to the factory. At this point, Element14 is claiming a delivery of 10-12 weeks on the Singapore website: that would just meet the deadline for the start of SMT production at the end of November.

I try to convince myself that I had found the solution to the problem, but something smelled rotten. A month later, I check back into the Element14 website to see the status of the order. The delivery had shifted back almost day-for-day to December. I start to suspect maybe they don’t even carry this part, and it’s just an automated listing to honeypot orders into their system. So, I get on the phone with an Element14 representative, and crazy enough, she can’t even find my order in her system even though I can see the order in my own Element14 account. She tells me this is not uncommon, and if she can’t see it in her system, then the web order will never be filled. I’m like, is there any way you can cancel the order then? She’s like “no, because I can’t see the order, I can’t cancel it.” But also because the representative can’t see the order, it also doesn’t exist, and it will never be filled. She recommends I place the order again.

I’m like…what the living fuck. Now I’m starting to sweat bullets; we’re within a few weeks of production start, and I’m considering ordering 18,000 oscillators and reselling the excess as singles via Crowd Supply in a Hail Mary to recover the costs. The frustrating part is, the cost of 300 parts is small – under $200 – but the lack of these parts blocks the shipment of roughly $170,000 worth of orders. So, I place a couple bets across the board. I go to Newark (Element14, but for the USA) and place an order for 500 units (they also claimed to be able to deliver), and I re-placed the order with Element14 Singapore, but this time I put a Raspberry Pi into the cart with the oscillators, as a “trial balloon” to test if the order was actually in their system. They were able to ship the part of the order with the Raspberry Pi to me almost immediately, so I knew they couldn’t claim to “lose the order” like before – but the SiT8021 parts went from having a definitive delivery date to a “contact us for more information” note – not very useful.

I also noticed that by this time (this is mid-October), Digikey is listing most of the SiT8021 parts for immediately delivery, with the exception of the 12MHz, 1.8V version that I need. Now I’m really starting to sweat – one of the hypothesis pushed back at my by the buyer in China was that there was no demand for this part, so it’s been canceled and that’s why I can’t find it anywhere. If the part’s been canceled, I’m really screwed.

I decide it’s time to reach out to SiTime directly. Through hook and crook, I get in touch with a sales rep, who confirms with me that the 12MHz, 1.8V version is a valid and orderable part number, and I should be able to go to Digikey to purchase it. I inform the sales rep that the Digikey website doesn’t list this part number, to which they reply “that’s strange, we’ll look into it”.

Not content to leave it there, I reach out to Digikey directly. I get connected to one of their technical sales representatives via an on-line chat, and after a bit of conversing, I confirmed that in fact the parts are shipped to Digikey as blanks, and they have a machine that can program the parts on-site. The technical sales rep also confirms the machine can program that exact configuration of the part, but because the part is not listed on the website I have to do a “custom part” quotation.

Aha! Now we are getting somewhere. I reach out to their custom-orders department and request a quotation. A lady responds to me fairly quickly and says she’ll get back to me. About a week passes, no response. I ping the department again, no response.

“Uh-oh.”

I finally do the “unthinkable” in the web age – I pick up the phone, and dial in hoping to reach a real human being to plead my case. I dial the extension for the custom department sales rep. It drops straight to voice mail. I call back again, this time punching the number to draw a lottery ticket for a new sales rep.

Luckily, I hit the jackpot! I got connected with a wonderful lady by the name of Mel who heard out my problem, and immediately took ownership for solving the problem. I could hear her typing queries into her terminal, and hemming and hawing over how strange it is for there to be no order code, but she can still pull up pricing. While I couldn’t look over her shoulder, I could piece together that the issue was a mis-configuration in their internal database. After about 5 minutes of tapping and poking, she informs me that she’ll send a message to their web department and correct the issue. Three days later, my part (along with 3 other missing SKUs) is orderable on Digikey, and a week later I have the 300 missing oscillators delivered directly to the factory – just in time for the start of SMT production.

I wrote Mel a hand-written thank-you card and mailed it to Digikey. I hope she received it, because people like here are a rare breed: she has the experience to quickly figure out how the system breaks, the judgment to send the right instructions to the right groups on how to fix it, and the authority to actually make it happen. And she’s actually still working a customer-facing job, not promoted into a corner office management position where she would never be exposed to a real-world problem like mine.

So, while Mel saved my production run, the comedy of errors still plays on at Element14 and Newark. The “unfindable order” is still lodged in my Element14 account, probably to stay there until the end of time. Newark’s “international” department sent me a note saying there’s been an export compliance issue with the part (since when did jellybean oscillators become subject to ITAR restrictions?!), so I responded to their department to give them more details – but got no response back. I’ve since tried to cancel the order, got no response, and now it just shows a status of “red exclamation mark” on hold and a ship date of Jan 2022. The other Singapore Element14 order that was combined with the Raspberry Pi still shows the ominous “please contact us for delivery” on the ship date, and despite trying to contact them, nobody has responded to inquiries. But hey, Digikey’s Mel has got my back, and production is up and (mostly) running on schedule.

This is just is one of many supply chain war stories I’ve had with this production run, but it is perhaps the one with the most unexpected outcome. I feared that perhaps the issue was intense competition for the parts making them unavailable, but the ground truth turned out to be much more mundane: a misconfigured website. Fortunately, this small corner of the supply chain is now fixed, and now anyone can buy the part that caused me so many sleepless nights.

November 29, 2021

Name that Ware, November 2021

The Ware for November 2021 is shown below.

This is another ware from jackw01, and I thought it was fitting for the season (that’s a hint, yes). The posting is a bit early this month because, good news: Precursor production is finally moving ahead! … and so, I may not have sufficient connectivity later this month to post at the usual time.

Andrew Huang's Blog

- Andrew Huang's profile

- 32 followers