Peter L. Berger's Blog, page 177

June 12, 2017

Leaving Paris in the Springtime

President Trump’s decision to void U.S. participation in the Paris Climate accord has already been flagged many times over as a political stunt to play to his “base” that was unnecessary from a policy point of view and hurtful from a diplomatic point of view. His ditching a carefully drafted, vetted, interagency-approved speech in Brussels in favor of a witless tirade—without telling his stunned-upon-delivery National Security Advisor, Secretary of State, and Secretary of Defense—stemmed from the same motive.

In this television-infused presidency, read “audience” instead of “base” and you get the psychomaniacal dynamic that drives this President: He cares about his own popularity, which feeds the insatiable demands of his insecurity, more than he does about nation he leads. In his mind, his former obsession with ratings for The Apprentice elides seamlessly into his obsession with the size of his inaugural crowd and his disdain for all the pollsters who now tell him what he does not wish to hear about his unpopularity in the Oval Office.

No one knows where Trump’s out-of-control ego chariot will careen next, or with what longstanding cultivated U.S. interest it will collide with and likely total. That is a dangerous state of affairs for the affairs of state to be in, certainly. But we must take care not to exaggerate the particulars.

Yanking the United States out of a global climate accord is not a Trumpean innovation. In 2001 George W. Bush pulled the United States out of the unratifiable 1997 Kyoto Accords, and the reaction from the global warming chorus was similarly hysterical. But even if ratified, Kyoto would not have worked any better than Paris is likely to.

Yes, there is a scientific basis for rising global ambient temperatures, and yes, there is a scientific basis for saying that some or much or even most of this warming has anthropogenic sources. But much of the political froth that bubbles up around the science is far more akin to religion: In its common extreme forms, it resembles the latest end-of-the-world cult, and like all cults it is impervious to genuine scientific doubt and debate, and tends to maximalist interpretations of both danger and guilt. Most such true believers could not pass a 10th-grade earth science midterm if their exquisite designer lives depended on it.

The gist of the TAI take on how to deal with climate challenges has been skeptical of the efficacy of the global conference approach that epitomized Kyoto and Paris. There are three generic problems with this approach.

First, by aspiring to maximum participation, it sacrifices rigor and enforceability to legitimacy. In all exercises aimed at global governance functions save those far below the political line of sight (like the IBS and the UPU), there is an unavoidable tradeoff between efficacy and legitimacy, so those who would design such efforts must choose with eyes wide open.

Second, taking a lowest-common-denominator approach in order to achieve maximum legitimacy cedes bargaining power to the weakest but most recalcitrant players, in this case to countries like India. The key result is a legitimated consensus approach that in fact delegitimizes the result in the countries implicated most in implementing the accord over time. A related secondary result is an undermining of trust between wealthier countries that have agreed to subsidize the implementation of the accord and poorer countries that have promised to spend the money as intended, but likely won’t. This arrangement essentially smuggled into the Paris architecture the charity model redolent of the traditional foreign aid business, a very bad and unpropitious idea.

Third and most important, Kyoto and Paris have both been based on the premise that the long-term benefits of reducing fossil fuel emissions justify the short-term economic costs of transitioning to renewables—as though no environmental problematics are associated with renewables should they rise to scale at current and future global GDP levels. We need to take apart this third problem with some care, since it constitutes a veritable cornucopia of error.

At present, if any of the relevant numbers can be believed, about 83 percent of energy use worldwide remains fossil fuel in origin—oil, gas, and coal mainly. No serious person believes that this level of use can be driven below 50 percent within the next twenty years if we trust to some combination of voluntary national emission caps and normal market behavior alone. To drive it down faster would require either: draconian government-enforced reductions in fossil fuel use that would depress GNP levels in wealthy countries and induce sharp constraints on the growth of developing countries; or a concerted international effort to accelerate the process of technological innovation, dissemination, and application to reduce emissions—and that innovation could include new ways of using fossil fuels as well as renewables of known and yet unknown types. The former approach overflows with political poison, and simply will not happen. The latter requires imagination, leadership, hard work, astute management, cooperation across national boundaries, and a bit of patience. Some choice, huh?

Now, some critics of the Kyoto/Paris approach to climate change issues have distorted the issue of costs. Even Bjorn Lomborg, who in my view has the basic idea right—that indeed, concerted and accelerated green-tech innovation is the best way forward—is guilty of this. The common criticism made by him and others is that even if Paris works as claimed, it’ll reduce emissions by less than 2 percent of what is necessary to get to the -2 degrees Celsius ten-year goal at a cost of $1-2 trillion. Lomborg’s numbers have come under fire by critics who accuse him of focusing on worst-case scenarios, but the basic message still shines through: Paris is a wildly expensive way to accomplish next to nothing.

Alas, it’s not so simple. First of all, to be able to calculate how much any reduction in emissions will lead to a slowing of warming trends implies that this relationship is well understood. It isn’t. There is more evidence of correlation than there is confidence in cause. Something similar is true in cardiology, for example, where there is correlation between cholesterol levels and incidence of heart attack and stroke, but the causal relationships are elusive, giving rise to the phenomenon wherein many pharmaceuticals that reduce cholesterol levels do not affect the incidence of heart attack and stroke. Something as complex probably makes it hard to get from CO2 measures to effects on temperatures. There are problems yet to solve, as most scientists recognize.

To take just one of these problems, not that not long ago an article appeared in the New York Times revealing that warmer temperatures, and the added moisture in the atmosphere that warming implies, has led to more vegetative growth on the planet. I had been waiting for years for a mainstream press article on this very subject. Again, for those of us who passed high school earth science, it’s sort of obvious that warmer temperatures and more moisture are going to accelerate plant growth, and plants—in case you forgot—take in CO2 and give out oxygen. So the idea that CO2 emissions just accumulate and float around up there forever isn’t true. The ecosphere has a way of cycling gasses (and pretty much everything else), which is why anyone with a pragmatic attitude toward this problem has recognized for years that a cost-effective and multi-useful way to mitigate the warming problem is to plant a whole lot of trees. Not that plant life can absorb gobs of added CO2 indefinitely; the point is that the relationship between temperature and the mix of gasses in the atmosphere is a dynamic one that current models do not capture with exactitude.

Then there is the matter of how CO2 gets into the atmosphere in the first place. Burning fossil fuels is one way, but it’s not the only way. Capital-intensive monoculture agriculture is another. A few estimates hold that deep tilling and a failure to re-seed agricultural land after harvest is responsible for as much as a third of carbon emissions. Most other estimates range from 10 to 24 percent, showing, once again, that it is not easy to trust any of these numbers. But even 10 percent is a lot and just half the highest estimate is even more, such that government-mandated smart agriculture techniques could reduce emissions much faster and in a vastly cheaper manner than Paris ever could.

That is not the end of error in this third problem domain. What does “cost” actually mean when it is used in this context? Who exactly pays the $1-2 trillion over ten years?

Well, one way to think of this is in terms of lost production, and hence lowered or constrained GDP levels. Any such costs would be borne by economies and hence societies as a whole, but the distribution of costs within societies would vary with their political economy arrangements. Such costs would be real, but as already suggested, neither wealthy nor developing countries are politically inclined to pay them beyond a very modest level. The other way to think of what “costs” means is in terms of the investments and adaptations involved in moving away from coal and oil and toward natural gas within the fossil fuel category, and moving away from fossil fuels toward renewables over all.

There is obviously a huge difference between thinking of a “cost” as production foregone and thinking of “cost” as saved capital spent as an investment in innovation. Since politics makes the latter sorts of “costs” vastly more likely than the former, it becomes easy to understand why practically every large corporation in the United States and abroad, especially those involved in energy, likes Paris. They stand to make a lot of money from the transition, and they are eager to attract investment of all sorts to make the necessary innovation happen. Yes, their stand on Paris has a public relations dimension, and yes, their employees and shareholders are as green-minded as the public in general. But make no mistake: Their attitude is not based mainly on unctuous sentiment, but rather on sound business sense.

One can think of the Paris approach, then, as constituting a large, sprawling, and essentially unmanageable incentive generator. It implicitly expects various national private sectors to innovate in such as way as to drive economies toward more environmentally responsible destinations. Fine; maybe this will happen. And maybe it won’t. It isn’t clear that the participation of the United States matters very much one way or the other: U.S. emissions are falling because of the greater use of gas as opposed to coal for electricity generation, and because of relatively slow demographic and economic growth. (Many European countries are in the same boat.) Alas, one of the “secrets” of the climate change business is that until very recently emissions have tended to rise in lock step with GDP growth, and GDP growth tends to be largely a function of demographic realities, no matter what public policy happens to be.

So the Paris confab may do some good over time, in the fashion described above. But there is clearly a better way. And that better way, alluded to above, is for the United States to lead an international green-tech innovation effort to accelerate the process of transitioning away from highly polluting to less polluting ways of using energy.

How? That’s easy: The U.S. government created ARPA-e to do just that on a national level back in 2007. ARPA-e was based explicitly on the DARPA concept that proved so successful in the national defense sector. Never mind the deeper history of its origins; suffice it to say that Congress failed ever to fund it properly, and the Trump Administration’s budget wants to zero it out despite the successes it has had operating even with a pauper’s budget. Not even a coconut is so stupid as to want to do such a thing, but there you have it. Instead of eliminating ARPA-e, the Trump Administration should be scaling it up and internationalizing it.

Just imagine if last week, when the Administration announced it was pulling out of the Paris Accord, the President had not in essence flipped the rest of the world the bird, but had said instead: “We recognize that you can’t beat something with nothing. We don’t think the Paris Accord is the best way to deal with the problem before us and the world, and we have a better idea. We want to accelerate innovation in the energy sector by creating a massive cooperative international R&D project, even bigger and better than the Manhattan Project was. We are not content to trust the private sector alone to deal with this challenge. We don’t have time for that and we recognize the occasional special need for government to serve the common good, like in infrastructure, with highly targeted investments. And in this case governments need to invest cooperatively for the common good of all mankind. We’re going to create a global ARPA-e.”

It is ridiculous, of course, to expect that the Trump Administration would ever think along such lines, let along say any such thing. But what really grieves me is that the Obama Administration, which so dearly wanted to “lead the world” when it came to climate change issues, suffered such a lack of vision that it failed to even remotely question the Paris paradigm and come up with something better.

If it’s not an outright sin to have wasted such an opportunity, then it is surely a disappointment, for now, in the age of Trump, the United States is locked into a neither/nor box: Paris won’t work well or at all, but neither will we devise and lead anything better. If the Obama Administration had created a global ARPA-e project that was by now showing promise and creating new good jobs here and abroad, could the Trump Administration have so easily walked away from it? Unfortunately, we’ll never know.

Suu Kyi to UN: Stay Out of Myanmar

Aung San Suu Kyi, once the darling of the human rights world, is rejecting calls for a UN probe into the persecution of Rohingyas in Myanmar, reports :

Last month, the U.N. appointed experts to lead a fact-finding mission to investigate widespread allegations of killings, rape and torture by security forces against the Rohingya, a Muslim minority who have faced discrimination in largely Buddhist Myanmar for generations.

Myanmar has rejected the mission.

“It would have created greater hostility between the different communities,” Suu Kyi told reporters in Stockholm after a meeting with Sweden’s Prime Minister Stefan Lofven.

“We did not feel it was in keeping with the needs of the region in which we are trying to establish harmony and understanding, and to remove the fears that have kept the two communities apart for so long.”

Suu Kyi’s decision is sure to be greeted by outrage from the usual suspects in the human rights community, who longed for a golden age of humanitarian enlightenment after the Nobel Peace Prize winner took office. As WRM explained in December, those hopes always rested on a kind of human rights fairy tale: “Aung San Suu Kyi was the beautiful princess guarded by the evil dragon of a military junta; the Western human rights community was the golden hero who freed the princess so that Burma could live happily ever after, with Rohingyas and Buddhist monks reconciling under the spell of Western liberal ideology.”

Of course, things are rarely so simple in practice. Suu Kyi understands full well that her continued effectiveness and/or survival as a political leader depends on good relations with the army. Hence her reluctance to press them over the Rohingya issue. She also knows that siding with the Rohingya over Burmese nationalists would be political suicide. Most Buddhist Burmese do not pity the Rohingya as a persecuted minority but resent them as a foreign entity only allowed in under British imperial rule. That judgment may seem backwards to Western eyes, but it is a deeply ingrained political reality that any leader of Myanmar must deal with.

Western human rights NGOs, alas, prefer not to understand these dynamics, choosing instead to grandstand from afar and chastise their fallen idol for failing to meet their lofty expectations. But given the complex political minefield she is trying to navigate, Suu Kyi probably is right that an intrusive UN probe would only inflame the situation more.

None of this will offer much comfort to the Rohingya people, who are indeed suffering immensely. But the tragic situation in Myanmar does offer useful lessons for the rest of us: history rarely moves in a straightforward line toward progress, and in multiethnic states divided by bitter historical legacies, democracy rarely means liberty and justice for all.

EVs Struggle in Green Darling Denmark

Denmark can rightfully boast to be one of the greenest countries in the world, but even in this clean-tech utopia, electric vehicles are struggling to break into the mainstream. EV sales are rising around the world, but they spiked sharply in Denmark. As Bloomberg puts it, “[Denmark’s] bicycle-loving people bought 5,298 of them in 2015, more than double the amount sold that year in Italy, which has a population more than 10 times the size of Denmark’s.” Since then, sales in the EU have risen 30 percent, but Denmark has broken from that pattern and seen its own citizens purchase 60.5 percent fewer EVs in the first quarter of 2017. As Bloomberg reports, this reversal is the result of the phase out of a generous tax break:

[It] turns out that [Denmark’s] phenomenal sales figures had as much to do with convenience as with environmental concerns: electric car dealers were for a long time spared the jaw-dropping import tax of 180 percent that Denmark applies on vehicles fueled by a traditional combustion engine.

In the fall of 2015, the Liberal-led government of Prime Minister Lars Lokke Rasmussen announced the progressive phasing out of tax breaks on electric cars, citing budget constraints and the desire to level the playing field. […]

The new tax regime “completely killed the market,” Laerke Flader, head of the Danish Electric Car Alliance, said in a recent interview. “Price really matters.”

Price obviously matters—it always does—and Denmark’s experience should serve as a warning against reading too much into the progress of green industries (like solar power or, in this case, electric vehicles) that are being propped up by market distorting subsidies or tax breaks.

For the electric vehicle industry specifically, this isn’t a major setback, because many of the automakers in this space are having success in bringing costs down to levels that are attractive for consumers, even without generous tax breaks. It is a heat check of sorts, though, and it suggests that the promised takeover of EVs is further away than its most ardent advocates (and environmentalists) might have you believe.

Beijing Builds Bridges to Nowhere

Massive bridges are going up all across China, The New York Times notes, in a simultaneous display of engineering ingenuity and economic folly:

The Chishi Bridge is one of hundreds of dazzling bridges erected across the country in recent years. Chinese officials celebrate them as proof that they can roll out infrastructure bigger, better and higher than any other country can. China now boasts the world’s highest bridge, the longest bridge, the highest rail trestle and a host of other superlatives, often besting its own efforts. […]

But as the bridges and the expressways they span keep rising, critics say construction has become an end unto itself. Fueled by government-backed loans and urged on by the big construction companies and officials who profit from them, many of the projects are piling up debt and breeding corruption while producing questionable transportation benefits. […]

A study that Mr. Ansar helped write said fewer than a third of the 65 Chinese highway and rail projects he examined were “genuinely economically productive,” while the rest contributed more to debt than to transportation needs. Unless such projects are reined in, the study warned, “poorly managed infrastructure investments” could push the nation into financial crisis.

China’s bridges galore are another sign of an economy that has run out of legitimate investment opportunities, but that nevertheless has a huge and politically well-connected infrastructure industry determined to build, no matter what. The gravy train fueled by this construction boom may be great for fat-cat officials, but for the rest of us it is another ominous reminder that China’s bubble could well burst soon.

The first sign of a coming economic slowdown is often a boom in high-speed rail projects. Bridges to Nowhere are the second step down this road.

Gas Prices Plunge to 12-Year Low

You’d have to go back a dozen years to find gas this cheap in America. The NYT reports:

The average nationwide gasoline price on Friday was the lowest for this point of the year since 2005, according to GasBuddy, a website and smartphone app designed to help drivers find the best deals at the pump.

The immediate cause of the price break was the shock to global oil markets that came when the Energy Department reported this week that domestic inventories of both crude oil and gasoline had surprisingly surged the week before despite heavy driving on the Memorial Day weekend.

It wasn’t long ago that Americans were paying $4+ per gallon at the pump, and today every driver will be happy to see those days receding in the rearview mirror. The economic effects of this are enormous. The vast majority of Americans devote a sizable chunk of their budget to gas, so the savings accrued at the pump affect people around the entire country and across all social and economic strata. But those savings are most welcome, of course, in our country’s poorest households, for whom a trip to the gas station represents a larger chunk of their spending.

Expensive energy, and in this case expensive gasoline, is a form of a regressive tax—it hurts the poor the most. The shale boom is combatting that not only at America’s gas stations, but also in the global oil and gas markets.

Macron Wins Big in First Round, Crushes Left

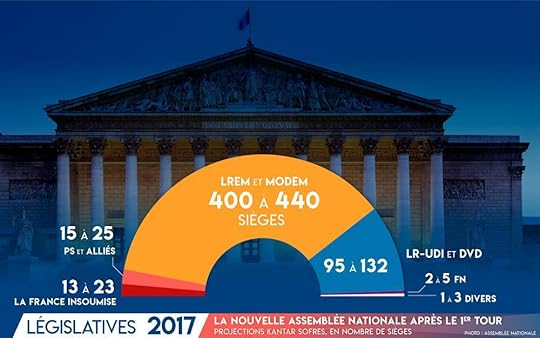

Emmanuel Macron’s La République en Marche outperformed earlier estimates in the first round of parliamentary voting in France this weekend and is projected to win as many as 440 seats in the parliament. As this infographic from Le Figaro makes plain, his victory represents nothing short of a rout:

These kinds of projections have historically proved rather accurate in French politics, with the exception of Nicolas Sarkozy’s disappointing showing in the second round in 2007 after predictions of a strong majority after the first. The fact that turnout this round, at 48.7 percent, was at historic lows, also suggests that the projected numbers might be at least a little soft.

But even if projections are off, this looks like a landslide for Macron, and an crushing humiliation for the Left in France. Even if En Marche proves to be a coalition so broad that some parliamentarians end up defecting piecemeal on some issues, it looks like far-reaching labor market reforms are likely to pass. The word is that Macron will spend the summer doing outreach to labor unions, with an eye to passing laws by September, ahead of Germany’s elections. Bond traders this morning are betting that he will be able to pull it off.

June 11, 2017

“Tear Down This Wall” at Thirty

Whatever the West does, it is likely that it will endure a significant threat to global peace and stability during the next few years. Despite President Trump’s apparent desire to work outside the current system, crises in Syria, North Korea, and elsewhere have already demonstrated that dramatic change is best managed when Atlantic nations maintain their unity. The confusion exhibited at the NATO, EU, and G-7 meetings in May does not bode well for Western unity in face of upheavals. Both the Trump Administration and the European allies bear blame for the confusion.

Ronald Reagan faced a similar dilemma as the Cold War began to wind down in the late 1980s. NATO had been deeply divided by Soviet military threats and by Reagan’s own sabre rattling early in his first term. But by 1987, the President had not hesitated to reach out to the Soviets through Mikhail Gorbachev, and he worked equally hard to rebuild NATO unity as a foundation for dealing with expected instability in the Soviet Union.

The coincidence of the thirtieth anniversary of President Reagan’s June 12, 1987 speech in Berlin presents an opportunity to compare his approach with American strategy today—in particular, to remember that the President’s famous speech was aimed more at rebuilding unity in NATO, and in particular with Germany, than at Russia.

When Reagan stepped up to the podium in front of the Brandenburg Gate, the Soviet empire was already on its last legs. But its aura of invulnerability continued to hold Europe in thrall—and especially Germany, which was drifting dangerously close to proposing a separate deal with Gorbachev to end the Cold War on Moscow’s terms.

Reagan’s immortal phase “Mr. Gorbachev tear down this wall,” is often given credit for putting into motion the dramatic events that followed. But the speech was actually mocked at first, considered naive and unrealistic until the Wall fell just shy of 18 months later. And it did not cause panic in the Kremlin, as many Reagan loyalists continue to believe. Neither did the Wall fall just because Reagan called on Gorbachev to tear it down.

My source for this judgment is Mikhail Gorbachev himself. I met him for a long discussion in 2009 on the fringes of a ceremony in Berlin, where he was to be honored for his contributions to peace in Europe. Gorbachev began by giving me a big hug. “We helped build peace in Europe,” he said through his interpreter. With Putin’s Ambassador looking slightly ill in the background, Gorbachev proceeded to give me his very colorful version of the world as he saw it after the famous 1986 Reykjavik Summit—a version perhaps colored by past-tense egoism, but likely as close to sound memory as we are liable to get.

Gorbachev began by rejecting firmly any thought that the Reagan speech caused panic in Moscow. The speech was not seen as a provocation; it was much more complicated, he said. “By 1987, Ronnie and I were already good friends. I still talk regularly to Nancy.” After all, he noted, the Treaty calling for destruction of all medium range missiles would be signed less than six months later. “I knew Ronnie was not going to let me down. “

Gorbachev said that in his view, if there had been any one reason for the collapse of the Soviet Empire, it was the dramatic decline of the oil price in the 1980s. Despite his friendship with Reagan, Gorbachev in 2009 still could not help but wonder whether the U.S. and Saudi governments had not colluded to keep oil and gas prices low to undermine the USSR. Market experts have repeatedly rejected this theory. But Gorbachev believed and perhaps still believes that if oil prices had gone higher, his reforms of the Soviet system might have worked.

But if the speech did not usher in the collapse of communism, it did play an important role: Its main message reached those for whom it was actually intended—those who lived in Germany. On June 12, 1987 Ronald Reagan made Germany an offer that was more dramatic and insistent than the road to appeasement that had been gaining popularity there for several years. Reagan placed the United States directly on the dividing line between East and West and made clear in terms echoing Martin Luther: “Here I stand; I can do no other.”

Those who had been echoing Soviet propaganda for years were thus made aware of an inescapable truth: Neither the United States nor the other Western allies were going anywhere, regardless of enticements from the Soviet Union. The image cherished by many Germans of Reagan as a warmonger and Gorbachev as a peacemaker thus became irrelevant to the real situation in Europe.

The Soviets had been working on their version of “alternative facts” for several decades. Historians have concluded that, by the 1980s, Moscow saw the hope of splitting Germany from the West as its last chance for maintaining influence in Europe. And they almost made it. Soviet propagandists of the 1980s were as skillful as Vladimir Putin’s are today in defining Russian offers as the logical road to peace. They tried to disrupt Western political life then much as Putin does today.

And the German public reaction was hauntingly similar to the mood in Trumpland America today: A deal with Russia was better than continuing confrontation. Leading German politicians, reaching far into the conservative CDU party as well as among the SPD, steadily increased pressure for an accomodation with Russia. Dissenting voices were rare.

The fall of the Berlin Wall would not have been possible with an Alliance in disarray, with a “rogue” Germany chasing appeasement toward the East. If President Reagan had delivered a different speech at a different spot in Berlin, as the German government lobbied hard to convince him to do, the political impact of his appearance at the very border between East and West would have been sharply reduced.

Had that happened, a collapsing Soviet Union would have continued to tempt the West with a false vision of peace. A bitterly divided Germany would have been torn between supporters of Western unity and those who wanted a special deal with Russia. Even Helmut Kohl had to play the game: Only 24 hours before the border opened in Berlin on November 9, 1989, he was in Poland to assure Lech Walesa, the country’s first non-Communist leader, that it would be “many years” before Germany was reunited. He really believed it, too.

What does this mean for today? Is a perfect storm already brewing? Chances are that it is. But it is especially ironic to note that this time America is losing interest in Atlantic unity, while Germany (with France) is holding firm. At recent summits in Europe, Donald Trump severely weakened Allied solidarity by leaving no doubt about his disdain for the European allies. America has now become the rogue nation and Chancellor Merkel has become the strongest advocate of a common and principled policy toward Russia.

Erosion of American leadership has taken place just as a severe economic and political crisis is once again making Russia unpredictable. Oil prices have again collapsed and political unrest is rising. Vladimir Putin’s cyber meddling and global propaganda attack has launched the 21st-century version of the 1980s.

The main issue here is not whether today’s Russia matches the global power of the Soviet Union. It doesn’t even come close. But it does have the ability to throw the West into chaos, if the irresolution and confusion of Western leaders persists. This is why Merkel, nearly alone among the Western crowd, is now so unbending. Trump may relish disruption, but Germany depends on stability and predictabilty to maintain balance within its still unsure national identity.

Trump’s boorish behavior at the May summits in Europe is only part of the problem. Less proximate but of equal importance is the Transatlantic security policy gap, which has been widening for years. This is a gap not mainly about money, or percentages of GNP spent on defense. It is a gap that is conceptual in nature.

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov brought things into focus at the Munich Security Conference in February 2017, leaving no doubt that Russia will test Western indecsiveness as far as it can. He said that Moscow was seeking a “post-Western world order.” Under this concept, each country would be allowed, “in accordance with the principles of international law,” to formulate its own definition of sovereignty, which established a balance between national interests and the interests of its partners.

Lavrov’s concept is a classic definition of big-power spheres of influence. It is in essence an attack on the cooperative approach to world security that emerged after the Cold War and it is nearly identical with Trump’s “Make America Great Again.” Threatening Mexico with a Wall is only slightly different than trying to intimidate Ukraine, but it is very different from Reagan’s plea to tear down walls.

If the Russian concept were allowed to spread, it would throw both Europe and the Middle East into disarray. Turkey, Poland, and Israel are only a few of the Western allies that would be forced to reconsider their policies. Angela Merkel, of all people, took a first step on May 28, acknowledging with regret that it may be time for Europe to move away from the United States. That was not a plaint of resignation; it was, in its own way, a sounding of the tocsin, an echo of Reagan’s June 12, 1987 speech.

Trump is a dramatic expression of American disengagement, but he is not the first. Both the Bush and Obama Administrations drifted steadily away from working with partners such as NATO. Behind this confusion is an American tendency to believe that the complex balancing of forces in Europe that characterized the Cold War is no longer necessary. Whatever their party affiliation, American experts tend to see terrorism and cyber crime as national American challenges—thus, Barack Obama’s relegation of Russia to the role of “regional power” after its invasion of Ukraine, and thus Hillary Clinton’s rejection of the Trans-Pacific Partnership even before it was cancelled by Trump.

For their part, Europeans continue to depend on American leadership, but they have done little to cultivate it. They are too consumed with the internal politics of the European Union. Their loss of trust in the United States has been reciprocated by growing American doubts that when the going gets tough, Europeans cannot be counted on.

It is in fact likely that a steady, unplanned, but nonetheless consequential “Amerexit”—the erosion of active American engagement in Europe and the Atlantic world—has contributed to sagging European defense readiness and stoked the controversies so evident at the NATO, EU, and G-7 summits this past month. Trump’s rhetoric and certainly his body language may be harsher, but a Hillary Clinton Administration would probably not have dealt much differently with America’s European allies.

There is a lesson to be relearned here. We are rapidly entering a globally integrated world in which cooperation across networks will require more rather than less cooperation with partners. Trump and Putin are in essence using a phony vision of past glory to build a political base that fears change. Luckily, the Atlantic community is already a coherent and integrated network that can adapt to new digital tasks much more readily than any comparable other. But success in its new role will require a sense mutual repect that is now sadly lacking.

Today’s immediate concerns, including terrorism, are tiny compared to the overwhelming task of getting control over the truly disruptive domestic and international implications of our digitized, disintermediating form of globalization. Today’s functional equivalent to the Reagan Berlin speech would be a wake up call making clear our need to strengthen civil society, both domestic and global, as a foundation for dealing with the daunting tasks ahead, including the military challenges. The fact is that without Atlantic unity Europe will also dissolve into competing visions and America will find itself fighting alone. Sadly, the May meetings demonstrated how far we are from agreeing on this goal, or even clearly seeing it. Maybe taking a new look at what Reagan did in Berlin will help us understand what is really at stake.

Will the Paris Pull Out Affect American Emissions?

Global emissions stalled in 2016 for the third year in a row, but they didn’t do so because of the Paris climate agreement (signed in December 2015). Instead, it was the United States leading the way, as we saw our own greenhouse gas emissions drop a whopping 3 percent during that year, helping to keep global emissions level even as the world economy grew. Contrast that with the EU—the world’s most vocal proponent of green measures—which saw its own emissions rise half a percent in 2015.

So how was America able to succeed where Europe has failed? The answer obviously isn’t the setting of climate targets—if it was, Brussels would have solved the climate problem by now. The real driver behind dropping U.S. emissions has been the shale boom, which has unlocked vast quantities of cheap shale gas that has displaced coal as the country’s dominant source of energy. Natural gas isn’t just cleaner than coal for the local environment, it also emits roughly half as much carbon dioxide as the sooty power source. Fracking is making America greener.

Donald Trump is as unlikely to attack the shale industry as he is to revive coal, which means the most important climate tool in America’s toolbox is going to be there for the foreseeable future. Next to that, the significance of our retreat from a voluntary, unenforceable accord seems to wane.

And with the top-down climate approach now dead on arrival here in the U.S., the bottom-up alternatives are getting a lot more attention. Shortly after Trump’s announcement, a coalition of U.S. states, cities, and businesses came together to pledge to adhere to the emissions reductions targets the president abandoned. That group seems to be giving credence to the notion that Trump’s pull out won’t affect U.S. emissions much. The AP reports:

The momentum of climate change efforts and the affordability of cleaner fuels will keep the United States moving toward its goals of cutting emissions despite the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the Paris global accord, business and government leaders in a growing alliance said Tuesday. […]

The momentum of existing climate-change efforts and the availability natural gas, wind and solar power mean those loyal to the Paris accord in the U.S. will have an easier time, with emissions expected to fall overall for years, said Robert Perciasepe with the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, who worked with Bloomberg’s group on the climate pledge.

Some studies suggest the United States will cut emissions as much as 19 percent by 2025 if it simply moves forward as is, he said. That’s not far from former President Barack Obama’s goals for a reduction of 25 to 28 percent as part of the Paris accord, Perciasepe said.

With the environmental movement galvanized, and this new coalition of states, cities, and industries more energized than ever before to commit to mitigation efforts, we might see the United States bridge that gap even faster outside Paris. Fracking will continue to reduce American emissions during Trump’s presidency, just as it did during his predecessor’s, and now that we’ve abandoned the predominant international climate strategy, grassroots alternatives will benefit from more time, money, and attention from greens. Given how ineffective the entire Paris endeavor has been, that could end up being a step in the right direction.

China’s Belt and Road Hits a Snag in Myanmar

China has been placing big bets on Myanmar recently, as it seeks to build crucial energy infrastructure for its Belt and Road initiative and regain influence after the country cozied up to Washington during the Obama years. As Reuters reports, however, China’s best-laid plans have been running into all kinds of opposition. The latest controversy is a much-delayed Chinese oil pipeline that has sparked protests and demands for compensation from local fishermen:

The pipeline is part of the nearly $10 billion Kyauk Pyu Special Economic Zone, a scheme at the heart of fast-warming Myanmar-China relations and whose success is crucial for the Southeast Asian nation’s leader Aung San Suu Kyi. […]

China’s state-run CITIC Group [CITIC.UL], the main developer of the Kyauk Pyu Special Economic Zone, says it will create 100,000 jobs in the northwestern state of Rakhine, one of Myanmar’s poorest regions.

But many local people say the project is being rushed through without consultation or regard for their way of life.

Suspicion of China runs deep in Myanmar, and public hostility due to environmental and other concerns has delayed or derailed Chinese mega-projects in the country in the past.

The Kyauk Pyu pipeline is just the latest Chinese project in Myanmar to hit a snag. Earlier this year, China suggested it would back out of a $3.6 billion dam project that had triggered large protests.

Similar problems are popping up in Pakistan. Beijing’s schemes there have sparked local unrest, and its early efforts have exposed the Chinese to attacks from local insurgencies and guerrilla groups. This very week, two Chinese nationals working on a Pakistani infrastructure project were killed by ISIS terrorists, in what could be an eerie sign of things to come.

China is often credited with far-seeing strategic vision for its ambitious development initiatives like One Belt, One Road. But Beijing’s early track record on these projects show that they are more likely to turn into boondoggles than success stories—and China will inherit a host of headaches as it seeks to turns its aspirations into reality.

China’s Belt and Road Hits A Snag In Myanmar

China has been placing big bets on Myanmar recently, as it seeks to build crucial energy infrastructure for its Belt and Road initiative and regain influence after the country cozied up to Washington during the Obama years. As Reuters reports, however, China’s best-laid plans have been running into all kinds of opposition. The latest controversy is a much-delayed Chinese oil pipeline that has sparked protests and demands for compensation from local fishermen:

The pipeline is part of the nearly $10 billion Kyauk Pyu Special Economic Zone, a scheme at the heart of fast-warming Myanmar-China relations and whose success is crucial for the Southeast Asian nation’s leader Aung San Suu Kyi. […]

China’s state-run CITIC Group [CITIC.UL], the main developer of the Kyauk Pyu Special Economic Zone, says it will create 100,000 jobs in the northwestern state of Rakhine, one of Myanmar’s poorest regions.

But many local people say the project is being rushed through without consultation or regard for their way of life.

Suspicion of China runs deep in Myanmar, and public hostility due to environmental and other concerns has delayed or derailed Chinese mega-projects in the country in the past.

The Kyauk Pyu pipeline is just the latest Chinese project in Myanmar to hit a snag. Earlier this year, China suggested it would back out of a $3.6 billion dam project that had triggered large protests.

Similar problems are popping up in Pakistan. Beijing’s schemes there have sparked local unrest, and its early efforts have exposed the Chinese to attacks from local insurgencies and guerrilla groups. This very week, two Chinese nationals working on a Pakistani infrastructure project were killed by ISIS terrorists, in what could be an eerie sign of things to come.

China is often credited with far-seeing strategic vision for its ambitious development initiatives like One Belt, One Road. But Beijing’s early track record on these projects show that they are more likely to turn into boondoggles than success stories—and China will inherit a host of headaches as it seeks to turns its aspirations into reality.

Peter L. Berger's Blog

- Peter L. Berger's profile

- 227 followers