Peter L. Berger's Blog, page 173

June 19, 2017

Why We Need Foreign Aid

In March 2017 the Trump Administration sketched out a “skinny” budget to Congress, and on May 23 it formally introduced that budget. America First: A Budget Blueprint to Make America Great Again calls for an $11 billion cut for the State Department, including USAID, which amounts to 29-31 percent of its total budget, depending on how you count. This was the second largest cut for any set of programs, exceeded only by a proposed 31 percent cut in the budget for the Environmental Protection Agency. The budget calls for a $52 billion increase for the Department of Defense (10 percent). The only other agencies that receive proposed increases of more than 1 percent were Veterans Affairs (6 percent) and the National Nuclear Security Administration, which oversees nuclear weapons and other security-related nuclear programs (11 percent). If passed, the budget—or anything closely resembling it—would not make America greater than it already is; it would make America less secure.

The base funding for the Defense Department is already 15 times larger than the base funding for State, USAID, and the Treasury Department’s international programs. Although the U.S. military might not have quite as many band members as the State Department has Foreign Service Officers, the numbers are not that far apart. Combatant commanders have their own planes and arrive in any foreign capital with a large entourage. Assistant Secretaries of State have no planes and fly commercially.

Hard military power is clearly essential for addressing some of the security challenges facing the United States, especially those coming from hostile and potentially hostile foreign powers, notably Russia and China. These challenges are fairly straightforward, but even in these cases military power is necessary but not sufficient. Short of major war, policy aims to prevent hostile powers from jeopardizing U.S. interests and those of its allies. Containment and deterrence require clarity, and clarity is a function of the orchestration of words and deeds—otherwise known as diplomacy.

Consider one case to illustrate the point: Would the United States really defend the Baltic States if one or more of them were invaded or subverted by Russia? Would it put New York or Washington at risk for Tallinn or Riga? Having the military power to credibly do such things is the backbone of a policy intended to obviate war without sacrificing interests. The complementary non-military components of deterring hostile or potentially hostile great powers are just as critical, but less tangible and more fragile. The United States has in the past tried to make its commitments to Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania clear through treaty obligations and presidential rhetoric, but Donald Trump has already undermined the credibility of these commitments by questioning the value of U.S. alliances, however much he has tried to backpedal. Trump’s rhetoric lowered the constraints on risky actions that the Russian leadership might take in the Baltics and in other former-communist areas in Europe. Increasing the Defense Department budget cannot by itself undo that.

The other major security challenges confronting the United States are less traditional and less straightforward but arguably not less important. They include defending against transnational terrorism, pandemic diseases, and the effects of massive migration—challenges that cannot be adequately addressed using the resources of the Department of Defense alone. This is something the current Secretary of Defense knows quite well and has often said. All three threats have a common source: poorly governed, failing, and weak or malign states.

Terrorist attacks can arise anywhere. The husband in the San Bernardino murders, Syed Farook, was raised in the United States and attended California State University Fullerton. But he was inspired by ISIS ideology via the internet. Failed and badly governed states—Libya most recently, as the Manchester attack shows—provide safe havens for radicalized Salafist Islamic groups such as ISIS and al-Qaeda, places where they can train adherents, propagate their message, and refine their ideology. These groups and the individuals they inspire are a direct security threat to the United States, a threat that has been amplified by the fact that nuclear or radiological bombs might be secured from failed, malign, or badly governed states and that biological pathogens can be more easily fabricated by individuals or groups.

Naturally occurring pandemic diseases are a second threat. About 400 diseases have jumped from animals to humans over the past seventy years. Most of them have originated in tropical areas where humans are encroaching on areas previously populated only by animals. Up until now we have been lucky. The best known of these diseases, HIV/AIDS and Ebola, are relatively difficult to transmit. A disease that was transmissible through the air instead of via bodily fluids could kill hundreds of thousands, or even millions, of Americans. Stopping these diseases when they first break out is our best line of defense. This requires strengthening the health infrastructure in poorly governed states.

Finally, massive migration threatens both liberal and humanitarian values. European states have been most afflicted by the massive displacement of people from wars in the broader Middle East. There are no good policy options to address such movements once they begin: Accepting unlimited numbers of individuals is untenable; sending refugees back to unsafe countries could make Western government complicit in a humanitarian catastrophe. Our best policy option is to prevent such flows in the first place.

Successfully addressing these and other threats that do not fall into the category of major-power competition requires two functions: understanding, which comes from good intelligence and even better analysis; and policy options available from a wide-ranging toolkit. That toolkit includes foreign assistance.

Foreign assistance is in fact a very versatile tool. It can vary from more or less straightforward bribes, to supporting not-so-attractive foreign rulers whose interests nevertheless complement or align in some manner with our own, to building state-capacity, to assisting selected countries in a position to move along a path to consolidated democracy. These uses of foreign assistance are directly related to the threat to American national security posed by transnational terrorism, pandemic diseases, and other non-traditional challenges, all of which emanate from badly governed or weak states.

We ignore badly governed, failed, and malign states at our peril because even states with very limited capacity can threaten the security of the United States. It is easier to ignore these threats when straightforward, more or less old-fashioned great power issues take center stage, but it is still a mistake to do so. If states are reasonably well governed, at least if they have adequate internal security, then terrorism, potential pandemic diseases, and massive migrant flows can be better contained. If states are weak, failing, or governed by malign autocrats, our security challenges will be greater because of them.

It is, though, very difficult to put failing, weak, or malign states securely on the path to democracy and a market-oriented economy. We need to use foreign assistance primarily to enhance our own national security in the short and medium term. The rich democratic countries of North America, Western Europe, and East Asia are historically the exception, not the rule. For almost all of human history in all places on this globe, governments have been rapacious and exploitative. There has been precious little by way of law-based accountability for political rulers; power has flowed from the barrel of a gun or the tip of a spear or the string of a bow. Political rulers have fed their cousins and those who commanded the weapons to stay in power. Governments that occupy the Madisonian sweet spot—strong enough to maintain order but accountable enough to not be oppressive—have been and remain relatively rare, and there is nothing inevitable about more such governments coming into being. There is no natural progression from poverty to prosperity, from autocratic rule to democratic rule.

We in the West, the providers of foreign assistance, should accept a sobering conclusion: Where we can make a difference in transforming poor governance into better if not democratic governance, we have a clear self interest in doing so; but it is very hard to make a sustainable, transformative difference. In most cases we will not be able to make countries into Denmark or even put them securely on a path to Denmark. This puts a premium on keeping our eye on the longer-term goal, on being patient, and on constantly looking for opportunities and better techniques to advance our goals.

Alas, patience is not something the American public is particularly good at, which is one reason that, especially among non-meliorist-minded conservatives, foreign assistance has never been popular. That certainly seems to be the case in the current Republican Administration. Many conservatives see foreign assistance as the foreign flipside of welfare, which they like even less.

That said, the skeptical brief against foreign assistance is not pure wind. Although foreign assistance has been a widely accepted practice for the past 55 years—USAID and the Peace Corps were both born by Executive Order in 1961—its record of accomplishments is frustratingly thin. In the 1950s, the widely held assumption in the United States and elsewhere, derived from then-dominant modernization theory, was that if countries received foreign aid they would be able to close the investment gap; if they were able to invest more they would grow faster; if they had higher levels of growth they would have a larger middle class and a larger middle class would be the foundation for a democratic political regime.

This very optimistic and straightforward story has, alas, not come to pass. The only larger country that has substantially changed its place in the international ordering of wealth and democracy, going from poor and autocratic to rich and democratic, is South Korea. The per capita income of South Korea at the end of the Korean War was at the same level as the colonies of West Africa; today South Korea is a member of the OECD with a per capita income above $25,000. Most of the countries that were poor in 1961 remain relatively poor today, in many cases notwithstanding many billions of dollars worth of foreign aid.

The classic assumption of foreign assistance was that leaders want to do the right thing; they want to improve the living conditions of their own people. This assumption is wrong. What political leaders want most is to stay in power. In democracies they must respond to the demands of most of their people. In non-democracies, they only need to satisfy the demands of a small part of their population; those people, most of whom have guns, they need to keep them in power.

The United States thus confronts a genuine dilemma. For reasons associated with our own security—especially related to transnational terrorism and pandemic disease—we need to improve governance in badly governed states, but our traditional aid programs have not been successful. We therefore need to re-think the objectives of foreign assistance and to distinguish foreign assistance from humanitarian programs that save lives even if they do not change polities. Our fundamental objective should be American national security. We need to identify programs that are consistent with our own interests and with the interests of political elites in target states. We have to find the sweet spot where our interests overlap.

First, therefore, we have to work to change the incentives of leaders in relatively poorly governed states. Under the Bush Administration, the United States implemented a new program, the Millennium Challenge Account (MCA), which rewarded countries for doing well on third-party indicators of governance, investing in health and education, and economic openness. This program has worked. Countries near the threshold for receiving MCA assistance have changed their policies. Incentives matter. Abandoning the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which had a kind of MCA incentive structure built within it, was a very bad idea exactly because it sent the wrong signal to potential Asian partners and to countries that might still exert themselves to make the transition to democracy.

Second, the U.S. government needs to improve its intelligence about and relations with potential leaders in the developing world. The preferences of political elites in developing countries can vary from gross theft, corruption, and repression to patronage (a much better form of corruption than gross theft), some economic growth, and security with limited repression. The U.S. government needs to be able to identify flesh-and-blood partners, real individuals, with whom it can work. This requires engagement and intelligence, and so requires a larger Foreign Service, not a smaller one. When an American official picks up the phone, there should be someone he can call, someone he knows personally, at the other end of the line. Such programs have worked for the American military, which engages in extensive training for officers from other countries through the IMET program and in other ways. Our civilian officials should have the same advantages.

The fundamental objective of our foreign assistance program should be security, health, and economic growth. These three goals are consistent with our interests and with the interests of elites in target states, even autocratic elites. At times, the interests of the United States would best be served by paying off the right foreign leaders. Both effective growth strategies and even pay-offs require a larger foreign aid budget, not a smaller one.

All leaders want security. They want to be able to effectively control their own territory. If they can effectively control their own territory, they can address transnational terrorist threats. Security assistance, especially strengthening the policing capabilities of poorly governed states, is an objective we should prioritize. And while such assistance may and usually does involve the Defense Department, is has always been and still needs to be organized and implemented by the State Department including USAID.

Better health is the big success story of the postwar period. In many countries life expectancy has increased by 30 years. Even in some very poor countries like Bangladesh, which now has a per capita income of $1,200, life expectancy increased from 46 years in 1960 to 72 years in 2014. All leaders can reap some benefits from the better provision of health. Various international programs, such as the elimination of smallpox, which was led by the World Health Organization, and national programs such as PEPFAR, which was initiated by the George W. Bush, have saved lives and highlighted American generosity. Ebola was halted relatively quickly in Nigeria because of a polio-monitoring program that had been put in place by the Gates Foundation.

All leaders will accept some economic growth if that growth does not threaten their own political position. Poorer states will not easily become dynamic market economies where economic changes can threaten the political leadership, but political leaders will want to provide more jobs for their populations. No foreign assistance program can guarantee sustained positive growth over the long term, and foreign assistance is usually less important overall than sound macroeconomic policies and freer trade. But aid programs can build capacity and human capital, and they can thus build a foundation for growth and higher levels of per capita income.

In addition to security, health, and economic growth there are two other objectives that American foreign assistance broadly understood can address. First, we can limit the impact of humanitarian crises. USAID has expertise in addressing these issues, especially via its highly skilled DART teams. The United States has been a rich and generous country. Abandoning humanitarian assistance would be a violation of American values, and would threaten our security by widening the area of ungoverned spaces.

Second, we might be able in some special circumstances to stop conflicts before they spread or mitigate their impact after they have taken place. Smaller agencies, such as the United States Institute of Peace (I have been a member of the USIP Board for several years) can contribute to these goals. UN peacekeeping missions may be acceptable to conflicting parties because they are politically neutral; the use of these missions can save American lives. Programs like those of USIP and UN Peacekeeping missions can save American lives and treasure. Cutting them, as the budget proposes, would make us less safe.

To guarantee our security we need a strong military, but it must be a military that we do not have to use very often. Whenever we are faced with a choice abroad between passivity and sending the cavalry, it is a sign of antecedent error. Diplomacy and development are complements to defense, not rivals: As Colin Powell recently put it, they prevent the wars we can avoid, so that we fight only the ones we must. Effective American leadership requires the three “D”s working in concert: defense, diplomacy, and development. But we need development programs that address the world as it is, not as we would like it to be—development programs that are hard-nosed, patient, and clearly conceived not as a form of charity but as an investment in our own interests.

Even before the specter of the “skinny” budget arose, U.S. foreign assistance in relative terms has been paltry, near the bottom of OECD countries as a percentage of GDP (though still the largest in absolute terms in most cases). And as a percentage of the U.S. Federal budget, development assistance is tiny—less than 1 percent. Indeed, those who dislike foreign aid almost always wildly exaggerate how much money we spend on it. In our own self-interest, we should be providing more foreign aid, not less, as we refine our approaches to the many serious challenges that development aid, along with other policy instruments, addresses. Cutting the budgets of the State Department and USAID in such a massive way would both crush morale and cripple crucial capabilities, making the United States less secure. To borrow a phrase from our British cousins, if ever a policy notion were penny-wise, pound-foolish, the budget’s approach to State and USAID is it.

The post Why We Need Foreign Aid appeared first on The American Interest.

U.S. Tries to Outlaw Shell Companies

The United States is going to try to outlaw shell companies once more, the Financial Times reports:

Charles Grassley, Senate judiciary committee chairman, and Sheldon Whitehouse, a Democratic colleague, are early next week set to introduce legislation that would require all US states to track the true owners of corporations. Though similar proposals failed last year, growing evidence of Moscow’s use of corporate vehicles that obscure their owners’ identity has revived prospects for action.

This is smart—and necessary. In the old days, the danger of Russian and Chinese oligarchs using shell companies to conceal their ill-gotten wealth in the West was more a nuisance for the U.S. than a real threat. But that is changing as both Putin and Xi tighten their control over their countries and show every sign of weaponizing investment.

The U.S. government needs to know who owns foreign corporations making strategic investments in the United States—and the sooner the better.

The post U.S. Tries to Outlaw Shell Companies appeared first on The American Interest.

Low Turnout and Macron’s Partial Victory

The big news this Monday is that Emmanuel Macron has achieved his sweeping victory in French legislative elections. On paper, at least, he is now the youngest and most powerful French leader since Napoleon.

But there is a problem: turnout. Both in the presidential and the legislative elections, a lot of French people didn’t bother to vote. Only 44 percent of voters bothered to show up for the last round of parliamentary elections.

Some of it was the lack of suspense. Macron’s En Marche party was so heavily favored to win that a lot of people saw no reason to vote. And some of it was genuine disillusionment with the tired alternatives on offer; the Left, especially, took a shellacking.

But there’s something else: French history, from Louis “L’etat c’est moi” XIV, through the Emperor Napoleon, right down through the Fifth Republic with its powerful Presidency, is the story of a country that likes a strong executive.

That said, France is a country that likes to rebel, and the opposition Macron really has to worry about isn’t in Parliament; it is in the streets. Low turnout could be telling us that many French voters feel alienated from formal political mechanisms; if that’s true, they could show their true feelings when the inevitable strikes and demonstrations against Macron’s proposed economic reforms start to take shape. As Benjamin Haddad noted in his essay in our pages last week, all that Macron has so far proven is that “many political institutions, up until now assumed to be immovably solid, are in fact very fragile and up for grabs.” His victory does not make the country necessarily less volatile.

Louis XVI, Napoleon, Charles X, Louis Philippe, Napoleon III, even de Gaulle: French history is full of leaders who seemed to be in full control of the country thanks to their mastery of its institutions—until, quite suddenly, they weren’t. Macron has conquered the world of institutionalized French politics; it remains to be seen whether he can master the street.

The post Low Turnout and Macron’s Partial Victory appeared first on The American Interest.

Pumphrett Finds Work for Idle Hands

“It was all the fault of that damned dog,” declaimed my friend and former schoolmate Pumphrett as we walked on the Virginia side of the Potomac opposite the Jefferson Memorial. I had always preferred the walk on the District side, with its view of the Custis-Lee Mansion and Arlington. But the Air Force had erected what looked like a gigantic metal coat hook near the Pentagon, forever disfiguring what had been a lovely prospect. My mood wasn’t helped by Pumphrett’s latest non sequitur, and I inquired with some irritation what on earth he was talking about.

“My fall from grace,” he grumbled. I was aware that Pumphrett was no longer in favor at the White House but had hesitated to ask the cause. People rose and fell in that abattoir of ambition like bits of used tissue on ocean tides (this morning’s report, for example, had Bannon up, Jared down, and Spicer out), so Pumphrett’s eclipse was no surprise. Still, he seemed eager to explain, so I let him.

“I think I told you, Cushy, that I took the gaff when the Comey firing went south. But the possibility of redemption was mooted if I could make a success of a most delicate mission: finding a dog for the White House.”

“I thought Trump hates dogs.”

“He does. Unconditional love offends him. But Ivanka insisted, and he finally agreed as long as they kept the smelly thing away from him.”

“And you were to find a suitable one.”

“I knew it had to be an undiscriminating breed. But which? Then, an inspiration! Trump likes blond things. Back when his sap was still running, he always targeted—and sometimes even married—blond women, and lately he has even become a sort of blond himself. So a golden retriever seemed perfect, and I found a nice one. I admit, I grew quite fond of it. Then another problem arose: What should it be called? Bannon suggested “Rudi,” but the dog wasn’t vicious. Finally, a masterstroke! I proposed “Blondie.” The name just popped to mind. Instant success! Ivanka gave me an air kiss in the hallway, the unveiling was set, and I allowed myself an extra tipple or two that evening in celebration.”

“So, a triumph.”

“Oh, on the contrary. When I arrived the next morning, no one was willing to meet my bleary gaze, and Spicer was assuring the press that there was no dog, and had never been a dog. I have no idea why. All I know is that Bannon was in higher than usual dudgeon and told me I would have been fired had it not been for uncle Pontius. (Pumphrett’s uncle Pontius Pumphrett had been an early Trump enthusiast, to the point of offering to endow a Pumphrett professorship at Trump University. That offer was withdrawn when his nephew explained to his credulous elder that the University thing was just a money-making scam. Still, the incident had provided Pontius with political pull, which he now apparently had deployed.)

“What happened to Blondie?”

“I heard that young Miller volunteered to dump her, minus tags, somewhere in Fairfax County. He enjoys that sort of thing. But never mind. The important thing is that, as a result, I’ve been given the most thankless task Steve Bannon could devise. I’m to find something to keep Tillerson busy.”

Pumphrett went on to describe his meeting with Bannon, who complained that Secretary of State Rex Tillerson was carping about his lack of relevance—and had recently taken to reminding everyone that he had once been a “big man in oil and gas.”

“This was annoying. ‘We pushed him out front to shill for the Muslim ban,’ Bannon had complained, ‘but nothing seems to satisfy the guy.’”

I remembered the scene—three elderly white men in identical dark suits shuffling before the cameras, led by someone I took at first to be the evil king of the pixies but turned out to be Attorney General Jeff Sessions. Tillerson had seemed uncomfortable on that occasion—like a man who had suddenly realized what was being done to him.

Weren’t there a few second-rank funerals to attend, Bannon wondered, or perhaps a meaningless UN conference or two? I said I’d find out and was going out the door when he added: ‘just make sure he gets the slow plane.’

“The first step,” Pumphrett went on, “was to discover what Tillerson was doing now. No one seemed to know, so I betook myself back to Foggy Bottom. The place was deathly silent. My knock on the great mahogany doors of the Secretary’s suite at first brought no reaction, but finally the doors opened a crack and a careworn face appeared—a woman, I concluded. ‘Who are you?’ the face questioned. ‘Pumphrett,’ I offered, thinking my coming had been foretold. Apparently not. ‘Are you from downstairs?’ this Cerberus demanded. ‘If so, buzz off!’ I assured her that I was not a member of the State Department staff, as she seemed to assume, but rather an emissary from the White House. She looked skeptical, but after examining my White House pass she gestured me inside with a jerk of her head. ‘Fifteen minutes,’ she snarled as I walked by.

“Tillerson, by contrast, was graciousness personified. He rose from behind a pile of briefing books as I entered and, in Trump fashion, painfully pumped my fin. So Steve had sent me, he beamed. That was fine. He hoped good old Steve was feeling better. Well, Cushy, I had no idea what he was on about. Bannon looks like death itself, of course, but that seems to be his natural state. It turned out that Tillerson had left a string of messages for Bannon, and—none having been answered—concluded that Bannon must be at death’s door. He looked disappointed when I assured him that this was not the case. But he rallied. ‘Never mind,’ he said. I was there now, fresh from Steve, and that was timely because he, Tillerson, had just been trying to decipher the latest Trump tweets and wanted to know—not to put too fine a point on it—what the hell was going on.”

“And you told him?”

“Of course not. I don’t know. No one does. But this is Washington, and one can never admit ignorance, so in answer to each of his questions I responded that I was not authorized to say, or that this was a matter best raised with Steve, or that the policy on that issue was under review. Finally he gave up and his shoulders slumped. Here was a man who had beaten his way to the top of the most heartless, grasping corporation on earth—a man who could claim personally to have raised global temperatures a couple of degrees Celsius—and he’d been undone by a jumped up carny barker with a spit combed coife. So I did something uncharacteristic. I gave him good advice.”

“You, Pumphrett!? I find that hard to believe.”

“No less do I, since what I told him can not possibly benefit me. Still, there it is. I told him he must stop asking the ‘why’ questions. ‘Why’ didn’t we confront the Russians, ‘why’ were we alienating the Germans, ‘why’ were we undercutting NATO? The President didn’t like ‘why’ questions, I told him, and anyone at the White House who valued his skin had ceased asking them. ‘But how,’ he bleated plaintively, ‘am I to know what policy is?’ This was exasperating, but I patiently explained that there was no ‘policy’ in the old sense of a consistent plan of action over a period of time leading to some desirable outcome. There were only tweets, each a discrete, redolent bolus of thought unconnected to anything that had come before or would come afterwards. These rained down at odd hours, and the disagreeable work of mashing them together for the benefit of the press could safely be left to Spicer or Huckabee’s offspring. As for Tillerson, he should manage foreign policy.

“‘But I’ve cut myself off from the staff,’ moaned this hopeless dunce. I tell you, Cushy, it was like talking to a child. So I explained to him that 97 percent of foreign policy was conducted outside the baleful purview of the Oval Office by professionals, many of whom actually knew what they were doing. With a little encouragement from him, that could be raised to 99 percent. Look what Mattis was up to at Defense. Did he think Mattis asked Bannon for advice? Indeed, the last thing Tillerson should do was look for guidance from the mouth breathers and lunatics at the White House, who would gut him like a fish for the least advantage and who, in any case, knew no more about the toxic stew of the President’s psyche than he did. In short, better to beg forgiveness than to ask permission

I had to sit down at this point, Cushy. I was little dizzy from the effort, not to mention the celebratory nips of the night before. Tillerson looked thoughtful. ‘But where should I start?’ he asked. Thankfully, I had given that some thought on the way over. He should start with the Gulf, I told him. He had drilled there for years and knew most of the rag-tag royals who had lately fallen out with each other for reasons only Allah understood. The President had dipped a toe in their troubles and made them worse. Why didn’t Tillerson fly out there and mediate—maybe sell all parties a few more guns. The outcome didn’t matter, since the President had come down squarely on both sides, and in any case the rum buggers would just find something else to squabble about.”

This rang a bell with me. I’d heard earlier on Fox News that Tillerson had offered to mediate and might even fly out to the region, provided anyone took the offer seriously. “So that was you, was it, Pumphrett? You’re the one who put starch in Tillerson’s socks. Well done! You know, you seem often to end up at the center of things.”

“Yes, but it’s lonely at the top. Speaking of which, I’ve got to go. My Uber has just pulled up, and I want to beat the rush hour traffic out 66.”

“Sixty Six! But you live in the District. Why are you headed out 66?”

“I’m going out to Fairfax to look for that dog.”

The post Pumphrett Finds Work for Idle Hands appeared first on The American Interest.

June 18, 2017

Obama Official: Obama Was Weak on S. China Sea

Writing for Foreign Affairs, former Joe Biden advisor Ely Ratner argues that the Obama administration failed to define credible consequences for China’s militarization of the South China Sea, thus enabling Beijing’s steady gains there:

In 2015, […] U.S. President Barack Obama said in a joint press conference with Xi, “The United States welcomes the rise of a China that is peaceful, stable, prosperous, and a responsible player in global affairs.” Yet Washington never made clear what it would do if Beijing failed to live up to that standard… The United States’ desire to avoid conflict meant that nearly every time China acted assertively or defied international law in the South China Sea, Washington instinctively took steps to reduce tensions, thereby allowing China to make incremental gains. […]

U.S. policymakers should recognize that China’s behavior in the sea is based on its perception of how the United States will respond. The lack of U.S. resistance has led Beijing to conclude that the United States will not compromise its relationship with China over the South China Sea. As a result, the biggest threat to the United States today in Asia is Chinese hegemony, not great-power war. U.S. regional leadership is much more likely to go out with a whimper than with a bang.

Later, Ratner suggests the kind of “course correction” that the U.S. could still lead to change China’s calculus in the region:

In order to alter China’s incentives, the United States should issue a clear warning: that if China continues to construct artificial islands or stations powerful military assets, such as long-range missiles or combat aircraft, on those it has already built, the United States will fundamentally change its policy toward the South China Sea. Shedding its position of neutrality, Washington would stop calling for restraint and instead increase its efforts to help the region’s countries defend themselves against Chinese coercion.

Will President Trump be able to implement the kind of forceful strategy Ratner has in mind? The jury is still out. Here at TAI, we have been encouraged to see the Administration recently launch a freedom-of-navigation operation (FONOP) after initial passivity, and Defense Secretary Mattis testified this week that such exercises would be a routine part of the strategy going forward. But it will take more than such exercises to prevent Chinese hegemony in the region—and Ratner’s article lays out a particularly muscular approach to change the game to our advantage.

The post Obama Official: Obama Was Weak on S. China Sea appeared first on The American Interest.

The Coming Conflict Over Eastern Syria

The Russians on Friday claimed to have killed the self-declared caliph of ISIS, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, in an airstrike in ISIS’ capital Raqqa. As the BBC reports:

The [Russian defense] ministry said an air strike may have killed Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and up to 330 other fighters on 28 May.

It said the raid had targeted a meeting of the IS military council in the group’s de facto capital of Raqqa, in northern Syria. [….]

This is the first time…that Russia has said it may have killed the IS leader. Other media reports have previously claimed he had been killed or critically injured by US-led coalition air strikes.

There are any number of reasons to doubt the Russian claims here. Reports in March suggested that ISIS’ leadership was already fleeing Raqqa. An Iraqi intelligence official told Reuters in response to the claim that they believe that Baghdadi is hiding somewhere in the sparsely populated Iraq/Syria border area. A gathering—as the Russians claim—of 30 ISIS field commanders, 300 guards, and Baghdadi himself all in one place would also be an uncharacteristic lapse in operational security for a man who survived the relentless pursuit of U.S. special operations forces in the late 2000s when the Islamic State of Iraq was nearly obliterated. Nor are the Russians above simply fabricating such claims—last August they falsely claimed responsibility for a U.S. airstrike which killed a prominent ISIS leader .

In other words, while we can hope that Baghdadi is dead, Russia’s claims may instead be part of an effort to take last minute credit for the approaching victory against ISIS in Raqqa.

In reality, it was the Kurdish SDF—backed by the U.S.-led coalition—that have done virtually all of the heavy lifting to attain that victory in defeating ISIS in Syria. The SDF’s methodical assault on Raqqa appears to be going well. Following President Trump’s decision to green-light an Obama Administration plan to provide the SDF with heavier weapons, they have surrounded the city on three sides and are squeezing ISIS from east and west.

Syrian Democratic Forces captured parts of al-Baryd district and reached the Military Intelligence Department

Map: https://t.co/QeXZATbIdy pic.twitter.com/Mcqiw4B7q6

— Syrian Civil War Map (@CivilWarMap) June 16, 2017

In Iraq, the Iraqi Army is now in control of almost the entirety of Mosul, once largest city under ISIS control, except for the warren-like Old City which still has as many as 100,000 people trapped inside.

What is clear is that while tough fighting against ISIS still lies ahead of us, we are looking at a situation in both Iraq and Eastern Syria where the unifying threat of ISIS is receding. While that has long been America’s goal, we now face a more confusing and potentially deadlier situation than the one posed by ISIS.

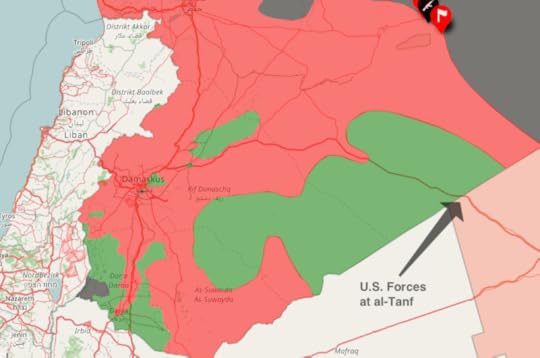

Iran’s goal in Eastern Syria appears to be to establish a land corridor linking Tehran with its clients in Baghdad, Damascus, and Beirut. Following a U.S. coalition airstrike against Syrian and Iranian-backed forces along the Baghdad-Damascus highway near the U.S. base al-Tanf last month, the Syrians have now reached the Iraqi border, effectively cornering our base.

Map from syriancivilwarmap.com.

While the U.S. is sitting on the main highway at al-Tanf, Russian media are reporting that the first Iranian weapons shipments bound for Damascus are already flowing across the Iraqi border. That has not yet been confirmed, and Iraqi control of western Anbar province on the opposite side of the Syrian border is tenuous, but is likely to improve. The precise danger of such a corridor compared with existing airlifts from Tehran to Damascus is probably unknown to anyone except analysts at CIA and the Pentagon (and their counterparts in Tel Aviv and Riyadh), but it would be easy to imagine Iran shipping heavier weapons, in greater volume, more frequently to Hezbollah and Assad.

Despite this apparent fait accompli, there’s no sign that the U.S. intends to withdraw from Southeast Syria. On the contrary, this week we deployed a sophisticated rocket artillery system to the base at al-Tanf for the first time. U.S. backed rebels could still, in theory, break out of the pocket and contest Syrian control of the border and try to link up with the SDF in the north. That would involve a race between the SDF and U.S.-backed rebels from the north and south against the pro-Syrian forces from the west towards the Euphrates and the border, likely converging on what will be ISIS’ last major city—Deir ez-Zour. White House officials reportedly want to go on the offensive against the Syrian and Iranian-backed forces in Eastern Syria despite resistance from Secretary of Defense Mattis and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, General Dunford.

Whether or not we want to contest that territory is one decision we will have to make soon about what we want in a post-ISIS Syria, before Syrian and Iranian-backed forces can solidify their control. To do so would involve a significant re-definition of the U.S. mission in Syria, a potential high-stakes confrontation with Iran and the Syrian regime, and an effective commitment to support our rebel proxies in holding that territory indefinitely. If the President seeks such a role for the U.S. in Eastern Syria, he should ensure that he has the support of Congress and is relying, as he so often claims, on the best advice of his generals and Secretary Mattis.

The other looming decision is what to do about the Kurds. The Kurdistan Regional Government in Iraq has set the date of its independence referendum for September 25th, 2017. There is no indication that the KRG, which has good relations with Turkey, is looking to include the Syrian Kurdish territories in an independent Kurdistan. The Syrian Kurds’ assurances that they want only greater autonomy within Syria, not independence, will be of little comfort to the Turks, who regard the Syrian Kurds as inseparable from the PKK insurgency inside Turkey. Above all other issues, our backing of the Syrian Kurds has driven a wedge between the U.S. and Turkey on the Syrian question and it’s not clear how they might react to either an independent Iraqi Kurdistan, or the Kurdish SDF gaining control of the entirety of Syria north of the Euphrates, as they seem poised to do.

Turkey’s President Erdogan has ominously hinted at an incursion into Northern Iraq which would effectively separate Iraqi Kurdistan from the Syrian Kurds. That would bring the Turks into conflict with some combination of the SDF and the Iranian-backed militias that control much of the Iraqi border area west of Mosul. The Iraqi government would be under intense popular pressure to resist any Turkish incursion into that territory and, once Iraqi Army troops are freed from the battle for Mosul, will soon have greater means to do so. The Turks did not inform the U.S. ahead of their initial incursion into Syria, which was likewise intended to thwart the Syrian Kurds, and would be unlikely to give us much warning ahead of an incursion to cut the link between the Iraqi and Syrian Kurdish regions.

While some of these scenarios are unlikely, they remain dangerously plausible. There is much that the U.S. can do now to press our interests while trying to prevent a wider conflagration. Should that fail, we also need to decide where our true interests lie should a much broader conflict break out in Eastern Syria and Northwest Iraq. As it stands, we have significant troop presences and military bases in Turkey, Iraqi Kurdistan, the Syrian Kurdish territory, surrounding Mosul, and in Southeast Syria. All of these would be under threat in such a conflict, with U.S. troops potentially based among both sides of opposing forces. These decisions won’t wait for Secretary of State Tillerson to implement his grand reorganization plans at the State Department next year, and they’re of far greater geo-political consequence than the President’s latest scandal du jour. The countdown has begun on the Iraq-Syria border, and we’re the only ones who don’t know what we want when it reaches zero.

The post The Coming Conflict Over Eastern Syria appeared first on The American Interest.

June 17, 2017

Turkish Opposition Politician Marches Against Erdogan

Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, the leader of Turkey’s largest opposition party, the Republican People’s Party (CHP), began a 280-mile march from Ankara to Istanbul on Thursday following the arrest of a CHP Member of Parliament. As Hurriyet Daily reports:

The protest decision was taken after CHP Istanbul deputy Berberoğlu was sentenced 25 years in prison on June 14 for “leaking state secrets” in the case into weapons-loaded Syria-bound trucks of the National Intelligence Agency (MİT), prompting a storm of reaction from the CHP.

Kılıçdaroğlu is set to march over 24 days to Istanbul, a distance of around 450 km, to the city’s Maltepe Prison where Berberoğlu was taken. He will walk during the days and stop at locations on the way. [….]

“There is no democracy in Turkey. But our march is a festival. Actually we are looking for justice and we are not worried,” the CHP leader said.

On the one hand the first such arrest of a CHP MP is yet another norm violated by the Erdogan government as he consolidates near-dictatorial control of Turkey. But the march also reveals the failures of the CHP in opposing Erdogan’s rise to attaining that power.

MPs in Turkey had long been constitutionally protected from prosecution until a vote stripped of them of that immunity in May of last year. The degree of immunity enjoyed by legislators is of course open to debate, but the concept of some degree of legislative immunity is an important norm of representative government, as found, for example, in Article 1 Section 6 of the U.S. Constitution.

The CHP position on the immunity vote was muddled. The CHP leader made statements in support of stripping immunity, but a majority of CHP MPs voted against the measure. So long as those targeted for arrest were from the pro-Kurdish HDP, which has had its two party leaders and 9 other MPs jailed—not to mention a slew of mayors and other lower level HDP office holders in what seemed to be a targeted effort to suppress the Kurdish vote—the CHP has remained fecklessly silent. Insofar as Kılıçdaroğlu now claims to march for all of the wrongly imprisoned journalists, academics, and other victims of Erdogan’s purge, we wish him well. But this is awfully late in the day for him to be making the kind of principled stand for the norms of liberal representative government that Turkey has long needed.

The post Turkish Opposition Politician Marches Against Erdogan appeared first on The American Interest.

Helmut Kohl (1930-2017)

Kings get monuments when they die. Democratic leaders usually slink off into obscurity once they are out. (Or they go to work for Gazprom like former German chancellor Gerhard Schröder.) Yet Helmut Kohl, who ruled for 16 years and died on Friday at the age of 87, deserves a place in history, as do Konrad Adenauer, who anchored his (half-) country in he West, and Willy Brandt, who achieved reconciliation with the East.

Like the heroes of myth, Kohl became a tragic figure once he was pushed aside by his protégée Angela Merkel in a classic instance of parricide. She would rise to the chancellorship six years later. Engulfed by a party financing scandal, Kohl soon fell ill, bound to a wheel chair and almost unable to speak. His wife killed herself, his son turned against him, his nation forgot the “Chancellor of Unity.” Yet he will be assured a seat in the Pantheon of German history—right alongside Otto von Bismarck.

The “Iron Chancellor” unified Germany with “blood and iron” in 1871. Kohl pulled off Unification 2.0 in 1990 without a shot being fired. Bismarck left behind a tottering European house that would implode in World War I. When the Berlin Wall fell, Kohl instinctively grasped that Germany would always be too weak to go it alone, but too strong to be left alone, and he acted with prudence and foresight.

So when East Germany collapsed into the arms of its rich brother, Kohl proved wiser than Bismarck. He knew that Berlin’s neighbors had to be reassured and compensated. The price of power was more European integration, including a common currency, plus the strengthening of NATO that anchored the U.S. in Europe as a counterweight to Berlin and Moscow.

Indeed, if in 1983, Kohl had not succeeded in hosting U.S. intermediate-range forces (cruise and Pershing II missiles) in the face of million-fold protest sweeping his country, NATO might never have recuperated from the blow. And the Soviets, who had deployed such “Euronukes” first, would have scored a historic victory. Kohl’s courage, we should conclude, was the beginning of the end of the Cold War—and the Muscovite empire in Europe. The Wall collapsed in 1989, and so did the Soviet Union just two years later.

End of empire, end of Europe’s partition with its barbed-wire fences and minefields running straight through Germany. Plus another windfall: Kohl was blessed with George H.W. Bush who cleared the path to reunification by cajoling Germany’s angst-ridden European allies and coaxing Moscow. Kohl added billions in ransom money paid to Moscow.

Recasting Europe without war, as Bismarck could not, Kohl implanted a peaceful order that will outlast the “Iron Chancellor’s” precarious construction. Kohl and Bush the Elder should have received the Nobel Peace Prize for reuniting Europe and Germany in total peace. They were certainly more deserving than Yassir Arafat or Barack Obama.

Yet history will deliver the far bigger prize. There is no “Fourth Reich,” as so many worried back then. Helmut Kohl, who rose from provincial pol to all-but-eternal chancellor achieved the impossible: a strong, indeed preponderant Germany, yet a power house safely “socialized” in a myriad European and Atlantic institutions.

The threat to that wondrous order now emanates not from Germany redivivus, not even from Vladimir Putin, but from Donald Trump who would “make America great” again by gnawing away at the bonds that have tied the U.S. to Europe for 70 years.

The post Helmut Kohl (1930-2017) appeared first on The American Interest.

June 16, 2017

Beijing Chips Away at Taiwan’s Friends

With Panama peeling away from Taiwan this week to establish ties with China, Beijing is making a renewed push to poach the island’s few remaining allies and diminish its representation abroad. Reuters:

China has been pressuring the United Arab Emirates and four other countries to ask Taiwan to rename its representative offices in another sign of diplomatic pressure on the self-ruled island, Taiwan’s foreign ministry said on Thursday. […]

The pressure from Beijing on the UAE, Bahrain, Ecuador, Jordan, and Nigeria follows Panama’s decision this week to cut diplomatic ties with Taiwan and instead recognize China and its “One China” policy.

Taiwan’s foreign ministry said in a statement China wanted the five countries to ask Taiwan to use names, such as “Taipei Trade Office”, that do not suggest Taiwanese sovereignty.

“China is acting to suppress us in an impertinent way that has seriously offended the sensibilities of Taiwan’s people,” the statement said.

This is part of a longer trend. Beijing has been steadily picking away at Taiwan’s 20 remaining allies for a while now, many of them small, developing countries in Latin America or Africa that have benefitted from Taipei’s largesse and are now receiving significant investment from Beijing. None of the five countries mentioned here, however, actually have formal diplomatic relations with Taipei. In this case, Beijing is objecting to the mere use of the name “Taiwan” for their unofficial missions, which suggests an expansion of China’s efforts to marginalize Taiwan even among countries that do not formally recognize it.

For its part, the United States has been inconsistent in its relationship with Taipei this year, to say the least. The Trump era began with a phone call that spurred high hopes that the U.S. would more strongly support the island, but those early overtures have not exactly been followed up on; to the contrary, Trump may even be delaying an arms sale to Taiwan in an attempt to propitiate China as pressure builds to do something about North Korea’s nuclear progress.

Of course, one has to assume that President Trump—not one to sentimentalize military alliances at all—at least sees value in the U.S. relationship with Taiwan insofar as it annoys the Chinese quite a lot. It would be a pity to grant Beijing any of these kinds of symbolic but nevertheless important victories in pursuit of one-off concessions on pressuring Pyongyang.

The post Beijing Chips Away at Taiwan’s Friends appeared first on The American Interest.

Trump’s Immigration Compromise

The Trump administration is taking fire from the Right and the Left for its immigration actions last night. Hardcore immigration hawks like Ann Coulter are apoplectic that the administration extended president Obama’s executive action granting provisional legal status to people who came to the U.S. illegally as children; left-wing activist sites like Fusion and ThinkProgress, meanwhile, are decrying the administration’s formal erasure of another Obama-era order that would have halted deportation for millions more illegal immigrants.

CNN reports on the details of the two actions, which were announced by the Department of Homeland Security:

The Trump administration late Thursday night officially rescinded an Obama administration immigration policy that would have protected millions of undocumented immigrants — but left intact a separate initiative for young immigrants.

The program, Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents, known as DAPA, had never actually taken effect after being signed in 2014. Courts had blocked it pending further litigation, which has been ongoing.

Given President Donald Trump’s opposition to the program, the Department of Homeland Security formally rescinded the policy rather than continue to defend it in court Thursday.

But the policy guidance made clear that DHS would continue to honor DAPA’s sister program, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA.

Of the two Obama orders in question, DAPA was always a more radical program. As CNN notes, DACA applies to just three-quarters of a million people while DAPA reaches six times as many–effectively granting amnesty to over a third of the U.S. illegal immigrant population, and possibly more. And while deferred action for “Dreamers” is broadly popular, President Obama’s order suspending immigration laws for millions of people who knowingly violated immigration laws as adults doesn’t have nearly as strong of a moral or political basis.

The announcements last night, then, seem like a reasonable compromise from an administration trying to govern from the center, even if they feel like more of a “win” for the pro-immigration side, because DACA’s future was very much in question but DAPA had already been halted by courts and it seemed unlikely to be revived.

That said, sweeping executive actions, whether by Obama or Trump, are no way to solve America’s immigration problems. If America is going to grant amnesty to Dreamers, that policy should be ratified by Congress, preferably as a part of an immigration package that cuts unskilled immigration levels and clarifies enforcement priorities. Sadly, despite some promising innovations by Republican senators, the Trump administration has not shown the interest or competence in negotiating lasting fixes for the U.S. immigration system. Until that happens, policy is likely to continue to swing wildly each time the ruling party loses the White House.

The post Trump’s Immigration Compromise appeared first on The American Interest.

Peter L. Berger's Blog

- Peter L. Berger's profile

- 227 followers