Peter L. Berger's Blog, page 174

June 16, 2017

China Seeks to Muzzle Chinese Exile

Guo Wengui, also known as Miles Kwok, has levelled personal accusations against Wang Qishan, China’s powerful anti-corruption tsar, from his home in Manhattan. The unproven, but gripping, allegations have transfixed the Chinese public as elite factions jockey for influence in the ruling Communist party.

In response, Beijing has entangled Mr Guo in at least five lawsuits, marking an unprecedented engagement with the US judicial system. That could prove an expensive distraction for Mr Guo, who relies on Twitter and overseas Chinese media for free airtime.

“No one anticipated that lawsuits against Mr Kwok would come out in such scale,” said Tao Jingzhou, of Dechert, a law firm in Beijing. Chinese companies have been defendants in the US but rarely initiated a complaint in a US court, he said.

Many believe that Mr Guo is attempting to drive a wedge between Mr Wang and Xi Jinping, China’s president.

Guo Wengui has been a thorn in Beijing’s side for months, lobbing explosive allegations against Wang Qishan in order to tarnish the leader of Xi’s anti-corruption purges. Many suspect Guo is being fed information by Wang’s rivals to undermine him before the Party Congress. For that reason, Guo should be seen as more an aggrieved, self-interested insider than a noble whistleblower. Regardless, his revelations have cast an unflattering spotlight on elite party machinations, while dragging the U.S. into a loaded factional battle in Beijing.

Earlier this year, in April, Voice of America abruptly cut short an interview with the tycoon after allegedly being pressured by Beijing. But China’s attempts to silence Guo have otherwise proven fruitless, while its arguments for extradition have fallen on deaf ears. The legal pursuit of Guo in the U.S. could signal a new tack, as Beijing seeks to bury Guo with litigation and catch him with violations of American law.

The dispute certainly could complicate Sino-American relations. Apart from the litigation, China is surely exploring diplomatic channels with the Trump administration to secure his return, and it is not lost on China’s leadership that Guo happens to be a Mar-a-Lago member. Whether the pressure on Guo in the U.S. will actually change the situation, however, is far from clear. In many ways, China’s attempt to silence a dissident oligarch in the U.S. is just a sign of basic patterns reasserting themselves, as the gaps between the U.S. and the illiberal giants of Eurasia continue to shape world politics in the Trump era.

The post China Seeks to Muzzle Chinese Exile appeared first on The American Interest.

Central Asia: All Together Now

After a quarter century of independence, the fragmentation of Central Asia is evident to all. A senior official there might justifiably complain about how each country “[is] pursuing its own limited objectives and dissipating its meager resources in the overlapping or even conflicting endeavors of sister states.” He might conclude that such a process,” carries the seeds of weakness in [the countries’] incapacity for growth and their self-perpetuating dependence on the advanced, industrial nations.” One can also imagine that another Central Asian official, seeking an alternative, might propose that “we must think not only of our national interests but posit them against regional interests: That is a new way of thinking about our problems.”

These words were spoken not by a Central Asian but by ministers from the Philippines and Singapore at the opening ceremonies for the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 1967. Prior to the founding of ASEAN, no one considered Southeast Asia a single region. Yet over forty years ASEAN has grown from five to ten members and become a model of intra-regional cooperation and coordination. And it has done so without diminishing the sovereignty of its members.

ASEAN was not the first such regional entity on the Eurasian land mass. Back in 1953 five northern European countries formed the Nordic Council, actually a council of councils, which organized inter-parliamentary consultations on energy, labor, finance, culture, business, and legislation, among other topics. While they share many cultural values, the Nordic countries differ on important issues like membership in NATO and the European Union. Nonetheless, the Nordic Union remains a model of collaboration built on strong sovereignties.

Against this background, the absence of such a purely regional entity in Central Asia is all the more striking. Indeed, the only two initiatives that come close are the 2011 declaration by five states there of a Nuclear Free Zone and the Aral Sea initiative. But both are limited to a single topic, and the Aral Sea project has lapsed.

This is not to say that the regional heads of states never get together. They do, but always under the sponsorship of an outside power. Russia has led the parade of outsiders seeking to impose their order on the region. Its Commonwealth of Independent States, Eurasian Economic Union, and Collective Security Treaty Organization all have Moscow-based secretariats but provide venues for at least sidebar discussions of purely regional needs. In 2001 China moved to catch up by establishing the Shanghai Cooperation Organization to deal with security and economic affairs. This can be very useful, but the sheer might of the large members tends to marginalize Central Asian concerns.

Beyond these conclaves, the Presidents and key Ministers of the five former Soviet countries (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan) meet at least annually with their counterparts from Japan, the European Union, Korea, and, since 2016, the United States. They also convene at the annual United Nations meetings in New York and other venues. But there is no entity of any sort that exists solely to foster areas of intra-regional cooperation and to coordinate Central Asians’ responses to the main issues of the day.

The Region That Isn’t

Why does this striking gap exist in the institutionalization of a historically rich region that once led the world in trade, commerce, science, and technology? The most common explanation is to blame the famously dyspeptic personal relations among Central Asian heads of state. However, history shows us that personal relations aren’t an impenetrable barrier: When Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan found it convenient to improve relations in order to develop a gas pipeline to China, their leaders quickly managed to set aside their private feuds and even five centuries of antipathy between their peoples.

Another line of explanation focuses on the narrow nationalism that postcolonial states everywhere exhibit during their uncertain first steps on the world stage. This “newly independent state syndrome” gave rise to the cult of Tamerlane in Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan’s passion for its oral epic, Manas, and the attempt by President Niyazov of Turkmenistan to pen a compendium of national values in order to unite the diverse Turkmen tribes.

In spite of this, the five Presidents of the new states banded together in 1993 to change the name of their region from “Middle Asia” to “Central Asia.” In 1996 several of them established a Central Asia Economic Union (CAEU). Turkmenistan alone held back, citing its nonaligned status. This body suffered from its members’ financial difficulties, from the West’s indifference, and from Russia’s opposition to a regional entity it did not control. Nonetheless, the CAEU fostered serious regional dialogue on such sensitive issues as water management, drug trafficking, and security.

So successful was the CAEU that Vladimir Putin asked to be admitted as an observer and then demanded that Russia be included as a member. Unable to resist their powerful neighbor, the CAEU admitted Russia. Putin promptly disbanded the group and merged its members into what later became the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU). From that time to the present, Central Asia has been without a coordinating body of its own. Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan have joined the EEU and the other three countries are feeling great pressure to do so. The point is not that the EEU offers no benefits (although evidence for this to date is modest), but that an entity whose two Central Asian members comprise only 13 percent of its total population and in which the GDP of just one member, Russia, is seven times larger than any other member cannot be a union of equals.

Central Asian nations pay a heavy price for the lack of cooperation and coordination among them. Five quite different bodies of commercial law, rules on currency, and visa requirements discourage foreign investors. They have long failed to address several excellent, mainly regional opportunities for cooperation like water, opening regular air links between capitals, and coordinating tariff regimes. Instead of intra-regional synergies there are disincentives. But regional cooperation would not threaten Russia, nor would it challenge national identities within the region. Rather, it would enable small countries to secure their identities in a regional context, and to gain the economic benefits of regional cooperation.

Because its constituent states have not forged a collective identity, Central Asia remains dramatically under-institutionalized. Indeed, by the standards by which regions are defined in the world today, it barely exists. This invites external powers to propose their own solutions and to advance them through divide and conquer strategies.

Further hampering the re-emergence of regionalism in Central Asia is the fact that most international agencies and even some Central Asian governments treat neighboring Afghanistan as if it belongs to another universe. Yet nearly half of the Afghan population belong to the same ethnic groups and speak the same languages as their neighbors to the north, and for 3,000 years Afghanistan was a major contributor to the culture of Central Asia as a whole. It also has the largest population in the region, is richly endowed with natural resources, sits at a major continental crossroads, and boasts a talented and worldly rising generation. The other Central Asian countries know this and will be quick to embrace Afghanistan once it is stabilized.

In fact, this is already happening. Within the past six months the Foreign Ministers of both Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan have journeyed to Kabul, and President Ashraf Ghani has visited all Afghanistan’s northern neighbors. Turkmenistan is forging ahead with the TAPI gas pipeline across Afghanistan to Pakistan and India, and Uzbekistan, which already provides Kabul with electricity, is planning a second phase of railroad construction in Afghanistan. In the same spirit, the World Bank’s CASA 1000 project will soon be sending electricity from Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan to Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Beyond these germinating economic links, Afghan students are already studying at universities in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Turkmenistan, and popular music flows in both directions across the Amu Darya (Oxus) River.

A new spirit of regionalism can be felt in every country of Central Asia. Many trace this to the greater openness of Uzbekistan’s new President, Shafkat Mirziyoyev, who, as a long-serving Prime Minister, was a shoe-in for the presidency. Nevertheless, in a very public campaign prior to the elections, he reopened regular flights to the Tajik capital (after 21 years) and sent his Foreign Minister Abdulazis Komilov to Bishkek to patch up relations with Kyrgyzstan. He also took steps toward making Uzbekistan’s currency more convertible, which would remove a major impediment to intra-regional trade. Of course, these trends can change. But the fact that Mirziyoyev gave such wide publicity to this new course suggests that he is prepared to rise or fall with the success of regionalism. Meanwhile, the presidents of Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan have held a series of meetings, and Turkmenistan has become the key driver of one of the region’s major projects, the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India Pipeline (TAPI).

President Nazarbayev of Kazakhstan is outspoken about the importance of Central Asia as a region with its own identity and interests. In a recent published speech before the Astana Club, he strongly affirmed the importance of Central Asians’ common history and values, their shared cultural and scientific achievements during its Golden Age a millennium ago, and the great relevance of these and other commonalities for the present. He is equally forthright in including Afghanistan as part of the region, and in calling for greater coordination among all six countries.

Leaders who may still tread cautiously about regionalism in the present do not hesitate to glorify it in the past. Two years ago President Karimov of Uzbekistan convened a conference of more than 300 participants from forty countries to discuss the heritage of such world-renowned Central Asian thinkers as Ibn Sina (Avicenna), Al Farabi, and Biruni. In his opening speech Karimov referred to these great minds as “OUR Ibn Sina, OUR Al Farabi,” and so on. Lest anyone think he was claiming them for Uzbekistan, he added that, “They’re ours, all of ours; they are our common heritage.” Even before this, President Berdymukhamedov of Turkmenistan had built a new park in Ashgabat featuring statues of these and other giants of Central Asia’s past. He, too, has insisted, “These great minds are our common heritage.” Many in the West dismiss both of these leaders as authoritarians. But when Afghanistan’s more democracy-minded President Ashraf Ghani uses the same language, one can be sure that something new is afoot.

As of now, these signs of an emerging regionalism remains inchoate. Even in their present form, however, they pose the question of whether the countries of Central Asia are on the cusp of creating some new kind of entity to reflect their common heritage and shared interests. Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan could provide the kind of leadership that France and Germany gave the European Union in its early days. We don’t know if or when they will seize this opportunity, but one thing is certain: that this is a matter for the Central Asians countries themselves to decide.

Central Asians are actively grasping toward giving the new spirit of regionalism some kind of institutional expression. This is the larger purpose behind Uzbekistan’s proposed region-wide initiative to devise a comprehensive water treaty that the UN can embrace and ratify. The Foreign Ministers have also met recently in order to plan a gathering of the Presidents, without outsiders. At that meeting, expected soon, the Presidents will chart out their future course of action. They are studying examples of regionally based consultative organizations elsewhere. ASEAN, the Nordic Council, the Arab-Maghreb Union, the Association of Caribbean States, and the East African Community are but a few of the possible models. A group of analysts in Kazakhstan has already called for such a regional approach, not in opposition to the many larger entities like the EU, SCO, or the EEU, nor as an alternative to the existing national states, but as a kind of second-story on the national houses that have successfully survived their first quarter century.

But key questions have yet to be answered. For example, will the new entity be purely consultative, or will it put forward programs of common action? If the former, will it have a permanent secretariat in one place or will it convene on a rotating basis in all the capitals and practice decentralization? Who will participate in such interactions: ministers and other senior officials, elective bodies and their various committees and commissions, non-governmental organizations, or some combination of all three? What fields will be covered: economics, security, social conditions, information, education, culture, or several of these together? Further, whatever topics the new body decides to address, will its actions take the form of recommendations or of binging commitments and joint programs? Finally, will such an entity permit non-members as observers and, if so, under what conditions?

Work with Central Asia, Not Around It

No one can say how the countries of Greater Central Asia will respond to these and other questions pertaining to their common interests. But the likelihood is strong that in the coming period such questions will rise to the forefront of regional discussion and debate. If that happens, it will pose an important challenge to major powers with which Central Asians maintain important relations, any one of which might perceive it as a significant challenge to their national interest. First among these will be Russia, and also China, the United States, and Europe, as well as such partners as Japan, India, South Korea, Iran, and the Gulf states. The worst scenario would be that they will be tempted to employ political, economic, or covert tools to influence the outcome of such deliberations, or even to prevent them from starting in the first place, as Putin has done over the past 16 years.

This should not happen. The major powers should stand aside and overcome the urge to intervene in self-organized cooperation among Central Asian countries. Earlier attempts to thwart the countries of Central Asia from identifying and discussing common concerns and interests failed. The Central Asia Union of the 1990s is no more, but the impulse that gave rise to it has revived and is stronger than ever. The major powers should understand that cooperation and coordination among the states of Central Asia is not against anyone. It is for Central Asia itself—its stability, and its peaceful development. Ultimately, it is also in line with the core interests of all the great powers. External powers should not seek to join or to attend meetings as observers. To the extent that the Central Asians themselves seek it they should be prepared to work with them as a collectivity, and in accordance with the rules they set for their joint activity. They should work with the Central Asians as a group, not around them.

All of the six countries of Greater Central Asia seek good relations with China, Russia, the United States, and the European Union. To this end they have embraced some form of balance as the key to such relations. If the six countries together affirm this principle, as is likely, then the big powers should accept it as a reality and should desist from interfering directly in the Central Asians’ regional deliberations.

It may be too much to expect external powers to abstain from interfering in the process of regional self-definition that is going forward today in Central Asia. Nonetheless, it would be wise for them to do so: A greater degree of cooperation and coordination across the region is a positive way to foster economic and social progress and to prevent such negative phenomena as drug trafficking, criminality, and radical Islamism. Above all, it has the real potential of promoting stability, which all major external powers profess to be their goal.

The post Central Asia: All Together Now appeared first on The American Interest.

A Smarter Approach to Cuba

President Trump will roll back major components of the Obama administration’s opening to Cuba with a new slate of travel and business restrictions, reports Reuters:

Taking a tougher approach against Cuba after promising to do so during the presidential campaign, Trump will make clear that a ban on U.S. tourism to Cuba remains in effect and his administration will beef up enforcement of travel rules under authorized categories, the officials said.

The new limits on U.S. business deals will target the Armed Forces Business Enterprises Group (GAESA), a conglomerate involved in all sectors of the economy, including hotels, the officials said, speaking on condition of anonymity. [….]

Trump will justify his partial reversal of Obama’s measures to a large extent on human rights grounds. His aides contend that Obama’s easing of U.S. restrictions has done nothing to advance political freedoms in Cuba, while benefiting the Cuban government financially.

Trump’s move comes at a moment of great Cuban vulnerability, when an eroding Venezuela is losing its ability to prop up Cuba’s failed economy. Estimates suggest that Cuba consumes 130,000 barrels of oil per day, but only produces 50,000 on its own. With the flow of crude from Venezuela now plummeting, Cuba is struggling to fill the gap—and has been desperately looking for foreign lifelines and investment. Trump’s renewed restrictions on tourism and business could make Cuba feel the economic pinch even more acutely.

Still, it is not clear what is the legal basis of preventing U.S. citizens from traveling to Cuba absent a Cold War-level security threat. American citizens should have the right to go where they want, and it is a serious American civil liberties issue to start telling us where we can and can’t go. Of course, the State Department is wise not to recommend that Americans schedule tourism to North Korea at the moment, and there is a legitimate national security reason to watch who goes to eastern Syria, for example. But today’s Cuba doesn’t meet that test.

Nor is it in the U.S. national interest to push the Cuban economy over the cliff. We shouldn’t be rescuing the Castro regime, but from the standpoint of American foreign policy, our lives would not be better if we added a Cuban succession crisis to the one shaping up in Caracas. Given the current chaos in Venezuela, we want to have some cards in our hands to affect Cuban behavior there. It is NOT in our interest for the Cuban government to help prop up the Maduro disaster, and increased Cuban economic dependence on flows of tourism would give us more ability to affect their behavior going down the road.

The smartest play for President Trump right now would be to let the Cubans know that he has zero emotional investment in Obama’s opening, stands ready to reverse it and even tighten things farther under certain circumstances, is deeply opposed to Cuban interference in Venezuela—and meanwhile leave the sword of Damocles hanging over Cuba’s head.

But it is Venezuela, not the ghost of the Bay of Pigs, that should be driving our Cuba policy these days.

The post A Smarter Approach to Cuba appeared first on The American Interest.

European Nationalism Isn’t Dead Yet

Political developments in Europe over the past six months—Angela Merkel’s ongoing strength; Emmanuel Macron’s sweeping victory; the humbling of Theresa May and declining prospects for a strong Brexit—have led many observers to conclude that the wave of populist-nationalism that once looked poised to engulf the Western world has now been decisively beaten back.

These prognostications could well turn out to be correct. The Merkel-Macron alliance, along with the possibility of a more integrated UK, may give the European project a second wind. But despite the upsurge of Euro-optimism of the past six months, many of the forces that were tearing the union apart and boosting populist parties remain potent across the Continent.

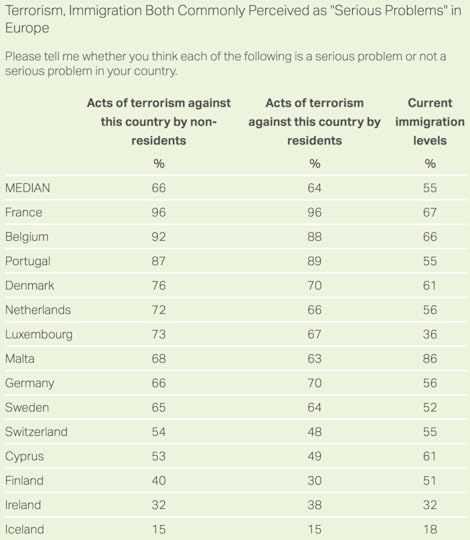

A new Gallup poll, for example, shows the persistence of concerns about terrorism and immigration. Notably, even though France handed the anti-immigrant Marine LePen a resounding defeat, more than two-thirds of French continue to see immigration as a “serious problem” for the country.

The European establishment’s enthusiasm at the way the political winds have been blowing over the past few months should be tempered by numbers like these. If the EU’s migration and refugee policy continues to be beset by incompetence and finger-wagging sentimentality while failing to Dassuage the legitimate concerns of European voters, the populists will be back, faster than you can say, “Schengen.”

The post European Nationalism Isn’t Dead Yet appeared first on The American Interest.

June 15, 2017

America’s Green Energy Workhorses Are Looking Long in the Tooth

The U.S. gets 20 percent of its power from nuclear power plants, but many of those reactors are due to come offline in the coming years, and there aren’t new projects coming down the pipeline. That’s an energy security problem, but it’s also an environmental one, and it’s (finally) catching the attention of environmentalists. The NYT reports:

The United States’ fleet of 99 nuclear reactors still supplies one-fifth of the country’s electricity without generating any planet-warming greenhouse gases. When those reactors retire, wind and solar usually cannot expand fast enough to replace the lost power. Instead, coal and natural gas fill the void, causing emissions to rise.

Some environmental groups that have long been hostile to nuclear power are now having second thoughts. “We don’t support unlimited subsidies to keep these nuclear plants open,” said John Finnigan, lead counsel with the Environmental Defense Fund. “But we are concerned that if you close these plants today, they’d be replaced by natural gas and emissions would go up.”

It’s a shame that it’s taking this long for the green movement to begin to acknowledge the value of nuclear power. This change of heart reflects a cultural shift at the center of modern environmentalism, as concerns about climate change are replacing ideals of conservation and an aversion to the “unnatural” that catalyzed green thinking and created this movement in the first place back in the 60s and the 70s.

That cultural shift is a step in the right direction, because it adheres more closely to science than what came before it. Making a boogeyman out of nuclear power or genetically modified crops is more about moralizing than it is about tracking more closely with the latest scientific progress.

Here are the facts: nuclear reactors are (next to hydroelectric plants, whose siting locations are severely limited) the only source of consistent, zero emissions, 24/7 baseload power. They can do what coal can’t, what natural gas, and even what wind and solar can’t: keep the lights on without contributing to global warming. That’s important, and it’s why these reactors form the foundation for sustainable energy mixes all over the world.

The large majority of these reactors are old though, and many here in the U.S. are nearing retirement. Not enough attention is being paid to how those energy sources will be replaced. There’s a host of new nuclear technologies beckoning on the horizon, from thorium reactors to molten salt reactors to modular reactors, each of which represent potential solutions to some of the energy source’s biggest problems.

America can replace retiring reactors, but it won’t be cheap or quick. It’s going to require political support and further funding of new nuclear R&D, and if greens were smart, they’d be making those issues some of their key areas of focus.

The post America’s Green Energy Workhorses Are Looking Long in the Tooth appeared first on The American Interest.

The US Is Exposing Europe’s Divide on Nord Stream 2

The U.S. Senate voted to expand sanctions on Russia today, and part of that expansion will target European countries who cooperate with Moscow’s efforts to build out its pipeline infrastructure into Europe. The FT has the details:

The most prominent target is the contentious Nord Stream 2 pipeline, which is set to start pumping gas from Russia to Europe in 2019, and is a flagship project for Kremlin-controlled gas monopoly Gazprom. “It sanctions those who . . . invest or support the construction of Russian energy export pipelines,” Mike Crapo, a Republican senator from Idaho who co-authored the amendment, said of the new proposal.

That’s a big deal, because Nord Stream 2 is being financed by a consortium of five European energy majors. ENGIE (based in France), OMV (based in Austria), Royal Dutch Shell, Uniper (based in Germany), and Wintershall (also based in Germany) collectively agreed back in April to pay for half of the pipeline expansion in the form of loans to Gazprom. This was the work-around decided upon so that the project might avoid running afoul of EU anti-competition rules. These new U.S. sanctions, however, could hit these companies.

Predictably, (some) European countries are upset. The WSJ has more:

Germany and Austria on Thursday sharply criticized the U.S. Senate’s plan to add sanctions on Russia, describing it as an illegal attempt to boost U.S. gas exports and interfere in Europe’s energy market. […]

“We cannot accept a threat of extraterritorial sanctions, illegal under international law, against European companies that participate in developing European energy supplies,” [German Foreign Minister Sigmar Gabriel and Austrian Chancellor Christian Kern said in a joint statement]. “Europe’s energy supply is Europe’s business, not that of the United States of America.”

Nord Stream 2 would double the capacity of a pipeline link between Russia and Germany (that transits the floor of the Baltic Sea). Critics say it will increase Europe’s dependence on Gazprom supplies of natural gas and leave the region more vulnerable to Moscow’s bullying. Proponents—led by Germany, which stands to gain the most from the construction of this project—see a chance to beef up their energy security by accessing more supply volumes.

On the sidelines of this debate sits Ukraine, which stands to lose the most if Nord Stream 2 goes forward. Much of Russia’s access to the European market has historically depended on pipelines that transit Ukraine, but after Moscow’s annexation of Crimea, Gazprom has actively sought alternative routes for getting its wares to its European customers, thereby depriving Kyiv of lucrative transit fees.

While many capitals in Europe are protesting the pipeline through the lens of checking Russian aggression and as a means of showing solidarity with Ukraine, the arguments ginned up by the pipeline’s supporters—Germany and Austria, for example, are accusing the U.S. of using these sanctions to aid its own LNG sales in the European market—underscore just how badly fractured Europe’s supposed consensus on energy policy has become. After all, many other European leaders have publicly clamored for U.S. LNG imports as a way to ease their dependence on Gazprom.

The post The US Is Exposing Europe’s Divide on Nord Stream 2 appeared first on The American Interest.

IMF Blinks On Greek Debt Relief

The clock is ticking as the Eurozone works to reach an agreement on bailing out Greece today. From the looks of it, Athens will indeed get a bailout, but the IMF will blink on the issue of debt relief. Financial Times has more:

Officials said the most likely deal would see the IMF formally join the Greek programme, but hold back from providing money to Athens until the euro area provides a greater level of detail on the debt relief it is willing to offer the country.

This would end a situation in which Berlin has insisted that the IMF participate in the bailout before it will release any more money to Athens, while the Washington-based fund has said Germany and other eurozone countries need to offer Athens major debt relief to make its repayments sustainable.

Such an arrangement would fall short of Athens’ expectations, but would unblock much needed money from its aid programme.

The deal here sounds like just the kind of short term, face-saving compromise that is minimally acceptable to each side but fails to address the underlying dispute. Germany gets the best deal, prevailing in its tight-fisted insistence against unequivocal debt relief for Athens while still getting the IMF signed on to the bailout, which was a crucial condition for Berlin. The IMF, meanwhile, will claim that it has not caved on debt relief, since the fund will not actually disburse money until a debt relief commitment is agreed at a later date.

As for Athens? Well, Greece is already grumbling that the deal is not generous enough, since the government has tightened its belt and implemented reforms in the expectation of debt relief that is still nowhere in sight. But it is unlikely to oppose its last best hope for a cash lifeline that will prevent Greece from defaulting on its loans in July.

In other words, all parties involved have agreed to kick the can down the road once more, with Wolfgang Schauble cementing his role as the clear decider. As we wrote last month, Schauble has been pushing all along for a “details later” deal to get the IMF on board with a bailout while delaying debt talks; today, he seems to have achieved that outcome. The crucial question is whether Schauble will soften his stance on debt relief after September’s elections—perhaps in line with a that would link the size of Greece’s debt relief to its economic growth—or if Berlin will remain as intransigent as ever.

The post IMF Blinks On Greek Debt Relief appeared first on The American Interest.

Alexandria and the Rise of Political Violence

On March 14, 2016—just past 15 months ago, but it seems a whole lot longer—I wrote as follows:

Donald Trump is…not just about the Republican Party’s nomination for President, and he is not even just about the presidential election. He is a harbinger, a warning, of a very deep strain of irrationality rising within the American body politic. He is, too, an incubator of potentially significant political violence. He has organized no para-military organization of course, but every time he threatens to punch someone in the nose he is, in effect, giving permission for his followers to be transgressive, not to exclude being violently so. If he is denied the Republican Party’s nomination for President, or, failing that, if he loses the November election, we should expect violent reactions—on what scale no one can say. We should start thinking now about how most wisely to deal with them.

Obviously, given what happened yesterday on a baseball diamond in Alexandria, it is now apparent that I should have added to that thought the prospect of anti-Trumpean violence should Trump actually get elected President. But 15 months ago that still seemed to me, and to most others, highly unlikely.

I confess to having worried that anti-Trumpian violence and pro-Trumpian counter-violence might break out in Washington, and perhaps elsewhere, on Inauguration Day—and in that, according to subsequent read-outs of U.S. Park Police planning, I was not alone. Mercifully, that did not happen to any significant extent. But since the Inauguration we’ve seen rising violence on campuses—the attack on Charles Murray at Middlebury, trashings after Milo Yiannopoulis appearances at Berkeley and other universities, the coldblooded murder of Richard Collins III near the University of Maryland campus—and at least two sucker-punch cold-cockings of Richard Spencer, Weimar-reminiscent scenes of street confrontations in Portland, Oregon, and more.

And we’re barely passed one hundred days of the Trump non-Administration. One gets the feeling that if the scandal heat were not focused on the White House with such intensity, and if any legislative “successes” existed to date, the level of violence might be worse. And it could get still worse.

But why? Well, first, as H. Rap Brown once put it, “violence is as American as apple pie,” and you don’t have to be a descendent of slaves to take the point. Reading John Wesley Powell’s post hoc 1869 description of Kit Carson’s terrorist war against the Navajo in 1863-64—as though Carson’s tactics were perfectly fine with J.W. Powell, the founder of the Cosmos Club—is enough to induce spasms of vomit (except perhaps in people who don’t mind if a Congressional candidate beats the crap out of a reporter in Montana, and then go and elect him in a landslide anyway).

No, of course, Montana notwithstanding, we mustn’t project 21st-century norms back into history; it’s nor fair or intellectual best practice. Yes, someone tried to assassinate Ronald Reagan in March 1981, hoping to add him to the list of martyred Presidents (Kennedy, 1963; McKinley, 1901; Garfield, 1881; Lincoln, 1865). The sharp point, however, is that, along with our continuing (and, some argue, strengthening) gun-nut subculture, outbreaks of political violence should not really surprise us. Americans did not expand over an entire continent during the course of three centuries, fighting a gruesome civil war along the way, by holding cotillion dances and offering items in trade to the natives. Pioneers turned ruralists needed guns, if only because there are bears and wolves, dear to harvest, and occasional lunatic neighbors and predatory passers-through. If he lacked a gun or a fairly easy way to get one, would the late, unlamented James T. Hodgkinson have been likely to assault Republicans at an Alexandria baseball practice, say, with a bow and arrow or a hunting knife?

Then there is the fact that, compared to most European and many other national states, America has always had a relatively small social idea on account of the newness and diversity of its immigrant roots, inflected in turn by its sprawling geography and relatively high rates of spatial mobility. America is not like Belgium, for example, where communities are so deep and long rooted that, as legend at least has it, many people never wander farther than a few kilometers from the town in which they were born.

So the remote backdrop for American political violence and its affinity for guns is wired into the American DNA. But that’s obviously not enough to precipitate political violence, or else the sort of thing that happened yesterday in Alexandria would have been happening pretty much all the time for the past century or so—and it hasn’t. We have to go back to 2011, with the Gabrielle Giffords shooting in Tuscon, to come up with a rough analogue to Rep. Scalise’s wounding yesterday, and before that my memory comes up mostly blank all the way back to the Weathermen.

So if we can establish some reasonable remote causes of recent American political violence, what about the proximate causes? It is not hard to make a short list: the decline in confidence in American institutions to solve problems; the polarization of politics and the incivility of political discourse abetted by mainstream and social media; the spread of mind-gutting drug habits; and the coarsening of popular culture via the commercial television- and Hollywood-produced norming of violence. No, this latter phenomenon isn’t new: a whole lot of people got killed in those Westerns back in the 1950s, for example. But combined with the other items on the list, it’s a new brew many Americans imbibe.

Beyond the obvious, my list would also include the Gerbnerian “mean world syndrome” more generally, on which I have written before, and which has been gaining on us for about fifty years. It would include the hemorrhaging of social trust generally (for whatever reasons we can debate). It would include increasing social-media induced isolation, which mitigates the peer regulation of social conduct; it is almost a certainty nowadays that the post-atrocity biographies of violence perpetrators include phrases like “he was a loner,” “didn’t speak much to neighbors,” “lived alone in a van,” and so on.

It seems to me, too—though I can’t prove this and it might sound elitist—that the sharp polarization of American political discourse has something to do with the suddenly huge number of people who have been injected with ample doses of half-assed education. Mark Twain saw the phenomenon at an early stage: “Soap and education are not as sudden as a massacre, but they are more deadly in the long run.”1

What Mr. Clements meant then, I think—or at any rate what I mean now—is that “higher” education induces the otherwise ignorant to think really for the first time in abstract terms, and abstractions are very shiny to the point of mesmerizing to those who are unaccustomed to working with them. The possession of mass-manufactured degrees from third-rate colleges leads some people to suppose that they understand more than they really do. Not that supposedly first-class universities don’t often produce similar results.

Half-assed abstractions taught and absorbed with smug assuredness can inspire the worst kind of self-confidence which, when married to a penchant for political activism, produces…well, it produces the kind of political class we have fairly recently acquired, and its concomitant inability to compromise regularly to get things done. If you have merely an interest or two, you can horse trade and logroll. But if you have mainly or only convictions—defined by Nietzsche as being “more dangerous enemies of truth than lies”—you can’t. And that is why, in this case, the old saw has it dead to rights: A little knowledge can be a dangerous thing.2

I don’t know what James T. Hodgkinson though he understood well enough to lead him to attempt mass murder. He seems to have been pretty cocksure about something. Until five minutes ago I didn’t know where the Belleville, Illinois, native went to school, what if any drugs he took, how much commercial television he watched, how much of a loner he was, or anything else about him. With the help of a little Googling, I now know that his Facebook profile (which has since been removed) told us, in part, “He went on to study at Belleville Area College, now called Southwestern Illinois College, and then transferred to Southern Illinois University-Edwardsville. He studied aviation at Belleville Area College in 1969, before transferring in 1971 to Southwestern Illinois. The university told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch that Hodgkinson took just two classes at the school and did not complete a term.” We also know from his Facebook profile that he imbibed a steady diet of Cable TV liberal “lite” talk-news: MSNBC, Rachel Maddow, and more.

Generic explanations for a phenomenon like rising political violence in America should never be expected to dot all the “i”s and cross all the “t”s of any particular incident. The same goes for Islamist terrorist atrocities and the modal “terrorist personality” various experts have been trying to work out. If Mr. Hodgkinson fits the description I laid out above to one extent or another, it proves nothing. It only suggests.

Finally, as Morris Fiorina pointed out in these pages some time ago, the polarization of political activists need not and, according to some now slightly aged data, does not suggest that the nation as a whole holds politically edgy views. But it could well be that one of the consequences of the Trump campaign and early presidency is the acceleration of a trickle-down effect whereby what was once mainly elite polarization is now becoming a deluge of contempt and even hatred among the masses. If that’s true, then what happened yesterday may become a lot less rare than we would wish.

1From “The Facts Concerning My Recent Resignation.”

2The original whole, from Alexander Pope, goes like this: “A little learning is a dangerous thing;/ drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring:/ there shallow draughts intoxicate the brain,/ and drinking largely sobers us again.”

The post Alexandria and the Rise of Political Violence appeared first on The American Interest.

Chris Christie’s Pension Gamble

The embattled governor of one of America’s most pension-indebted states is rolling the dice with a peculiar plan to pay for exploding benefits: Transferring ownership of the state lottery system to the pension fund. The Associated Press reports:

New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie is betting that the lottery is the ticket to shoring up one of the state’s most vexing money problems: ever-growing obligations to the pensions for public employees.

The idea of linking the lottery to pensions has been around for years, but legislation backed by the Republican governor was introduced this week to make the lottery the property of the pension system for 30 years.

Analysts and advocates say the deal — an arrangement that would be unique to New Jersey — probably won’t hurt, but there’s not a consensus on how much it might help.

“Where it does provide tremendous relief is optically,” said Lisa Washburn, managing director at Municipal Market Analytics, a firm that analyzes government bonds. “The numbers look better on a whole lot of levels. Whether or not they’re truly better is questionable.”

Just as there is no secret strategy to beat the lottery, however, there is no way for New Jersey to get around its gaping pension hole without serious pain and sacrifice. The lottery proceeds already go to fund critical state services; if those proceeds are transferred to the pension system, the state will need to find new money to pay for those services or cut them.

The main appeal of the lottery gambit appears to be an accounting trick. Because the lottery is valued at $13.5 billion, “gifting” it to the pension system will immediately reduce unfunded liabilities, allowing the state to reduce its annual contributions below what they would otherwise need to be. The problem is that in spite of its paper valuation, it’s not clear that the lottery is actually a liquid asset—that is, the pension fund might not be able to sell it to anyone at full price if it decided to cash out.

Christie’s plan, in other words, looks like another exercise in rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic rather than reforming the underlying problems that have caused unfunded pension liabilities to grow. This might be enough for the state to keep going in the short run, but it won’t stop the fiscal vise from continuing to tighten. At some point in the not-so-distant future, can-kicking won’t cut it anymore.

The post Chris Christie’s Pension Gamble appeared first on The American Interest.

Renewables Broke a US Record in March

Three months ago, for the first time ever, wind and solar energy supplied more than a tenth of U.S. electricity. That data comes to us courtesy of the Energy Information Administration (EIA):

For the first time, monthly electricity generation from wind and solar (including utility-scale plants and small-scale systems) exceeded 10% of total electricity generation in the United States, based on March data in EIA’s Electric Power Monthly. Electricity generation from both of these energy sources has grown with increases in wind and solar generating capacity. On an annual basis, wind and solar made up 7% of total U.S. electric generation in 2016.

Electricity generation from wind and solar follows seasonal patterns that reflect the seasonal availability of wind and sunshine. Within the United States, wind patterns vary based on geography. For example, wind-powered generating units in Texas, Oklahoma, and nearby states often have their highest output in spring months, while wind-powered generators in California are more likely to have their highest output in summer months.

Regular readers will have noticed our healthy skepticism of renewables over the years, but this hasn’t stemmed from an a priori rejection of the undoubtedly green energy sources, but rather a criticism of their ability to compete with fossil fuels without heavy government subsidy in order to deliver consistent, cheap energy to the consumer. Consistency and cost remain renewables’ biggest challenges, but to that latter point the technologies underpinning wind and solar power are incrementally improving and are dragging their price down in the process.

Of course, wind and solar are still receiving state and federal support, so it’s too early for greens to declare that they’re ready to take on our cheapest energy option at the moment—natural gas—on a national level. But in especially windy and sunny places, siting renewables makes a lot of sense, and we’re seeing that reflected in their share of the overall energy mix.

Wind and solar still haven’t solved their consistency problem, or perhaps more accurately their intermittency issue. When the sun isn’t shining and the wind isn’t blowing, consumers still need electricity. In this context, the rising share of renewable power generation is actually a growing problem, because it puts a tremendous amount of strain on grids that weren’t designed with these sorts of day-to-day fluctuations in mind. To this end, the perhaps politically motivated but still important grid stability review ordered by Department of Energy chief Rick Perry is looking more and more necessary. We need to know that our grids can handle these inconsistent power suppliers.

In the broadest sense, this all falls under the “good problem to have” category. It’s yet more evidence that we’ve moved out of an era of energy scarcity and into one of energy abundance. Almost everywhere you look here in the United States, concerns over the security of energy supply have diminished sharply this century, and where once we were worried about how to properly ration gasoline and keep the lights on without price gouging, today we’re concerned about how to build a clean and cheap energy mix. That’s major progress.

The post Renewables Broke a US Record in March appeared first on The American Interest.

Peter L. Berger's Blog

- Peter L. Berger's profile

- 227 followers