Peter L. Berger's Blog, page 169

June 25, 2017

Oregon Takes On Soaring Home Prices

One major and often neglected cause of the widening schism between elites and the public in America is housing policy. Upper-middle class communities across the country, especially in coastal metropolitan areas, have made it harder for new people to move in by slapping on new layers of land use regulation and requiring endless permitting procedures for new development. And they have every incentive to do so: Restricting housing supply in prosperous areas increases those property values in the short term, even if it slows upward mobility and job growth and puts homeownership out of reach for more people in the state or wider region.

Oregon legislators have taken a step to break this pattern by drafting a law that would force localities to streamline their permitting process. The measure applies to the whole state but is clearly aimed especially at Portland, the state’s NIMBY stronghold. CityLab reports:

Oregon has decided to do something to boost affordable housing in the state. A new law before the legislature has opened unexpected fault lines in the already fractured political debate over housing costs. The bill represents something of a mixed blessing for affordability boosters: it’s designed to remove barriers to new construction, but at the cost of local authority.

House Bill 2007 would make it harder for local governments to restrict developments that include affordable housing. The bill would require city or county governments to complete a review of an application for a development with affordable housing within 100 days. Given the high costs associated with permitting, this bill could help pave the way for apartments and homes that Portlanders can afford.

Representatives of local communities naturally take issue with the legislation, which they say will strip their autonomy and force their neighborhoods to develop in ways they don’t approve of. America has a strong tradition of local governance, and it remains to be seen whether it can pass, and if so, whether it can become a model for other states looking to curb “opportunity hoarding” by their politically powerful upper-middle class enclaves.

But measures like this should be given a serious look. Housing has long been America’s secret engine of wealth-creation, encouraging saving and family formation, and strengthening civil society. Right now, the machine is in danger of being snuffed out by the accumulation of self-interested regulations and red tape. We need to make sure it keeps running smoothly into the next generation, and that means looking for ways to break the NIMBY stranglehold on local development policies.

The post Oregon Takes On Soaring Home Prices appeared first on The American Interest.

The Link Between Fracking and Earthquakes Is Becoming Clearer

Parts of the United States have seen a sharp uptick in the amount of seismic activity over the past few years. These earthquakes are generally small in magnitude—in many cases incapable of being detected without sophisticated instrumentation—but their frequency is rising at an alarming rate. As the EIA reports, an increase in earthquakes east of the Rocky Mountains is particularly concerning, and seems to be centered on the state of Oklahoma. This new phenomenon is being linked with the storage of drilling wastewater in old oil and gas wells:

More earthquakes in these areas have coincided with the increase in oil and natural gas production from shale formations. Seismic events caused by human activity—also known as induced seismicity—are most often caused by the underground injection of wastewater produced during the oil and natural gas extraction process.

Before 2009, Oklahoma might have experienced one to two low-magnitude earthquakes per year. Since 2014, Oklahoma has experienced one to two low-magnitude earthquakes per day, with a few instances of higher magnitude (between magnitude 5 and 6) earthquakes that caused some damage.

Those readers familiar with the America’s many productive shale basins might be wondering why earthquakes are spiking predominantly in Oklahoma—after all, producers are storing wastewater from fracking in many of the country’s other shale hotspots. According to the EIA, Oklahoma’s stratigraphy is vulnerable to the seismic stresses induced by wastewater storage in wells:

In addition to the increased use of wastewater injection related to oil and natural gas production in the region, the geologic conditions in central Oklahoma are conducive to triggering seismic activity. The rock underlying the formations where disposal water is being injected in the region has existing faults that are susceptible to the changing stresses caused by fluid injection. Without these geologic conditions, induced seismicity would be much less common. For example, induced seismicity in the Bakken region of North Dakota and Montana is relatively rare.

On the one hand, this comes as something of a relief, because it suggests that the strong connection between fracking and earthquakes isn’t an existential problem for the most important energy development in the United States in a generation (or more). The problems Oklahoma is now facing don’t necessarily apply to the rest of the country.

Moreover, storing wastewater from oil and gas drilling in old wells isn’t the only option for shale companies. A cottage industry has cropped up to try and make recycling that wastewater economical, and some firms are looking at ways to frack shale rock without water at all. Then, too, there’s the option of storing this effluent in above ground ponds. These might not be the first choices of the shale industry, but it’s important to note that alternatives exist—and Oklahoma regulators are pushing the state’s drillers to employ them en masse.

This is a serious issue. It’s the most damning indictment of the shale industry that we’ve yet seen, and it’s a problem that demands a solution. We have a good grasp on what’s going wrong in Oklahoma’s shale fields, but now it’s time to fix it.

The post The Link Between Fracking and Earthquakes Is Becoming Clearer appeared first on The American Interest.

June 24, 2017

OPEC’s Output Cut Is Rotting from Within

OPEC is committed to, along with a group of petrostates outside of the cartel, cutting its collective production through March of next year in an attempt to help reduce the oversupply that’s weighed on global crude prices in recent years. But even after this coalition of oil producing states recommitted itself to this strategy earlier this month, prices continued to fall. Today, they sit at just above $45 per barrel, far below where OPEC would like it to be. As the New York Times reports, Libya bears a lot of responsibility for this:

[The] biggest wild card in the [market] equation — one that could tip prices at the pump from one day to the next — is oil-rich Libya, among the most unstable countries in North Africa. Contrary to the predictions of almost all experts, Libya’s production has climbed a wall of crisis in recent months to 885,000 barrels a day last week, roughly triple its production of only a year ago. […]

Libya’s success in the oil fields has been highly improbable at a time when the country is hopelessly divided between two competing governments and several hostile tribal and regional militias. Deals are made from week to week between oil officials and tribal groups seeking leverage in the southern desert just to keep pipelines open. And suddenly the tensions between Qatar and its Middle Eastern neighbors are echoing more strongly in Libya, threatening exports.

But the seemingly ungovernable country has already undermined OPEC’s efforts to cut production, and now Libyan oil executives are projecting that their production will reach a million barrels a day by the end of July, a level not seen in four years.

Before the 2011 uprising, Libya was producing 1.6 million barrels of oil per day (bpd). Today the country is far from those numbers, but it’s making progress towards topping 1 million bpd once again—back in April, it was producing around 700,000 bpd, while today it’s pumping 885,000 bpd. That’s a significant difference, when you consider that the coalition of petrostates have targeted 1.8 million bpd as their reduction target. Libya was excluded from OPEC’s part in these cuts—a natural exemption, given the country’s recent struggles—but its surprising resurgence is still a major headache for the cartel, and it’s undermining cuts to a degree that few expected.

That’s why, even as OPEC pursues cuts, its production is growing. That’s also why oil prices recently hit a seven month low. It’s a bad time to be a petrostate.

The post OPEC’s Output Cut Is Rotting from Within appeared first on The American Interest.

Shocker: Germany Snooped on U.S.

In a stunning revelation that should surprise no one with a basic understanding of spycraft, the German press can confirm: Berlin’s intelligence agencies have spent years spying on their American allies, despite Germany’s public outrage against Washington for doing likewise. From The Local Germany:

Germany’s foreign intelligence service long spied on numerous official and business targets in the United States, including the White House, Spiegel weekly reported Thursday.

The magazine said it had seen documents showing that the intelligence service, the BND, had a list of some 4,000 so-called selector keywords for surveillance between 1998 and 2006.

These included telephone or fax numbers, as well as email addresses at the White House as well as the US finance and foreign ministries.

Other monitoring targets ranged from military institutions including the US Air Force or the Marine Corps, space agency NASA to civic group Human Rights Watch.

Countries with the capabilities to keep tabs on their allies do so; this is a basic reality of foreign intelligence-gathering. The revelation here is more significant for once again highlighting the hypocrisy of Berlin’s response to the 2013 NSA scandal. At the time, Angela Merkel indulged in hectoring lectures against Washington, insisting that “spying on friends is not acceptable at all.” Later, Germany kicked out a CIA official and conducted a politicized parliamentary inquiry into the matter, constantly inveighing against their perfidious allies in Washington—all while apparently staying up to similar tricks.

To be fair to Merkel, the specific revelations here only go up till 2006, when she was just starting out as Chancellor. But that hardly means that Berlin has turned its spies’ eyes away from the United States. In any case, Merkel must be crossing her fingers that this story doesn’t land on the President’s desk—he seems to be a little sensitive when it comes to surveillance.

The post Shocker: Germany Snooped on U.S. appeared first on The American Interest.

Optimistic Renewables Study Gets a Reality Check

Two years ago, an incendiary study was published with a (seemingly) outlandish claim: it said that the United States could completely phase out the use of fossil fuels by 2055, and that it could do so without the use of carbon capture technologies or nuclear power.

That was an extraordinary claim back then, and the study’s lead author, Stanford University civil and environmental engineering professor Mark Jacobsen, defended his work after its release from skeptical analysts and scientists. This week he’s digging in even harder after a new study was released in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences—the same place that published the original report—that claims that the Jacobsen study “used invalid modeling tools, contained modeling errors, and made implausible and inadequately supported assumptions.” The MIT Technology Review has a good run-down of this scientist spate:

In the original paper, Jacobson and his coauthors heralded a “low-cost solution to the grid reliability problem.” It concluded that U.S. energy systems could convert almost entirely to wind, solar, and hydroelectric sources by, among other things, tightly integrating regional electricity grids and relying heavily on storage sources like hydrogen and underground thermal systems. Moreover, the paper argued, the system could be achieved without the use of natural gas, nuclear power, biofuels, and stationary batteries.

But among other criticisms, the rebuttal released Monday argues that Jacobson and his coauthors dramatically miscalculated the amount of hydroelectric power available and seriously underestimated the cost of installing and integrating large-scale underground thermal energy storage systems.

“They do bizarre things,” says Daniel Kammen, director of the Renewable and Appropriate Energy Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley, and coauthor of the rebuttal. “They treat U.S. hydropower as an entirely fungible resource. Like the amount [of power] coming from a river in Washington state is available in Georgia, instantaneously.”

Both the original study and the rebuttal rely on models and other research, and both sides are refusing to back down. Responding to the rebuttal, Jacobsen said that there was “not a single error in our paper.” In a letter he co-signed with three other Stanford professors, he called this newest critical study “demonstrably false.” One of the rebuttal’s co-authors, former associate director at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory Jane Long, explained that “[energy] issues are complex and hard to understand, and Mark’s simple solution attracts many who really have no way to understand the complexity,” explaining that “[it’s] consequently important to call him out.”

Judging by all the heated rhetoric, it seems that this disagreement is getting a little personal. That said, all this still well within the bounds of how good science should be vetted: in public arenas, with researchers seeking out the opinions of their peers. It may take some time for the dust to settle, but the simple fact that so many highly qualified scientists are taking the issue seriously bodes well for our chances of gleaning a better understanding of the underlying truth.

But with the caveat that dust is still in the air, Jacobsen’s original study still seems wildly optimistic to us, to put it kindly. If it were somehow possible to put the United States, with the currently available suite of renewable technologies, on a (cost-effective) path towards completely phasing out fossil fuels, we’d already be well on our way. The fact is, we’re not, because oil, coal, and especially natural gas still have major roles to play in our country’s energy future.

We’ll let the scientific method do what it does best. In the meantime, we reserve the right to be deeply skeptical of a sanguine study that doesn’t pass the sniff test.

The post Optimistic Renewables Study Gets a Reality Check appeared first on The American Interest.

June 23, 2017

On Brexit’s Anniversary, Brussels Rebuffs May

Today marks the one-year anniversary of the UK’s vote to leave the European Union, but the passage of time has still not brought clarity on what Brexit will look like—and European leaders remain seriously unimpressed by the divorce terms offered by Theresa May. Financial Times reports on the latest squabble:

Theresa May’s “fair and serious” offer to guarantee the rights of 3m EU citizens living in Britain has been given a cool reception in Brussels, as Brexit was pushed into the margins of an EU summit.

Donald Tusk, European Council president, said the proposals were “below our expectations”, while German chancellor Angela Merkel said they were “not a breakthrough”. […]

Although the UK proposals are viewed by EU negotiators as the basis for a possible deal, one diplomat said: “The idea that we should be grateful she isn’t going to deport people in 2019 is a bit strange.”

An important point of difference is the EU’s demand that European citizens should be able to uphold their rights in the European Court of Justice after Brexit, a position rejected outright by Mrs May.

The dispute here about the ECJ’s jurisdiction is not a mere detail; it is tied to a deeply rooted British resistance to foreign judicial authority. There is no easy middle ground on this issue, so it could turn into an intense game of chicken between London and Brussels.

Since the two sides first started butting heads on the issue, though, the power dynamics have seemingly shifted in the EU’s favor. With Theresa May’s election gamble having backfired in spectacular fashion, the Prime Minister is seen as severely weakened, with no clear mandate for the Hard Brexit she campaigned on. Indeed, public opinion in the UK seems to be shifting toward a softer divorce, even as two-thirds of Europeans are urging Brussels to take a hard line against the UK.

It’s a delicate dance: the UK is now sounding more open to staying inside the single market, but that runs counter to the goal of many European officials to impose a harsh and punitive divorce settlement that will scare off others from following Britain to the exits. At the same time, one of the main areas where the EU wants to preserve ties with the UK—the aforementioned preservation of the ECJ’s jurisdiction—could be a deal breaker for London. If Brussels overplays its hand and the two sides fail to reach a divorce agreement, the resulting “no deal” exit would be a disruptive disaster for all involved.

The dynamics are not pretty. At the moment we have an emboldened EU seeking to extract concessions (and a hefty bill) from a weakened UK, a Prime Minister hobbled by her electoral drubbing and lacking a clear mandate to pursue the hard Brexit she campaigned on, and publics in the UK and Europe whose visions for a departure are operating at cross purposes.

One year after the Brexit shock, there is still little evidence that Leavers regret their vote by any significant margin—but that doesn’t mean that finalizing the divorce won’t get ugly.

The post On Brexit’s Anniversary, Brussels Rebuffs May appeared first on The American Interest.

IEA Official Says Green Goals Doomed Without Nuclear

If you’re an environmentalist, make sure you’re sitting down for this: the world is going to need nuclear power if it has any chance at reducing greenhouse gas emissions to the levels deemed necessary by scientists to stave off catastrophic global warming. That’s what the International Energy Agency (IEA) said this week, when it cautioned that the coming scheduled decommissioning of an entire generation of nuclear reactors in the West is threatening the global effort to curtail emissions. Reuters reports:

Nuclear is now the largest low-carbon power source in Europe and the United States, about three times bigger than wind and solar combined, according to IEA data. But most reactors were built in the 1970s and early 80s, and will reach the end of their life around 2020. […]

[Governments] must expand renewable investments to replace old nuclear plants if they are to meet decarbonization targets, IEA Chief Economist Laszlo Varro told Reuters. “The ageing of the nuclear fleet is a considerable challenge for energy security and decarbonization objectives,” he said on the sidelines of the Eurelectric utilities conference in Portugal. […]

“If we do not keep nuclear in the energy mix and do not accelerate wind and solar deployment, the loss of nuclear capacity will knock us back by 15 to 20 years. We do not have that much time to lose,” he said.

This won’t come as any great surprise to those familiar with the unique merits of nuclear power—next to hydroelectricity, it’s the only source of zero-emissions baseload power. Unlike wind and solar power, the typical green energy darlings, nuclear can be relied upon to keep the lights on 24/7, independent of the vagaries of daily weather. Simply put, nuclear reactors are the green energy workhorses upon which any sort of future sustainable energy mix must be built.

And yet, we’re seeing fear mongering greens getting their way in countries like France, where newly-elected president Emmanuel Macron’s pick for energy minister is intent on dismantling the country’s massive fleet of nuclear reactors (which account for roughly three quarters of France’s electricity).

Here in the United States, our own reactors are quickly reaching the end of their life cycles, and there aren’t any new plants coming down the pipeline to replace them. When they retire, they won’t be replaced by wind or solar power—intermittent renewables can’t be substituted for the baseload power nuclear contributes. Instead, it will be fossil fuels like coal or natural gas stepping up to the plate, and they’ll be emitting greenhouse gases in the process.

There are a host of new nuclear technologies that could form the backbone of the next generation of reactors, but policymakers aren’t pursuing them with enough urgency. Nuclear power is as good for global energy security as it is for climate change mitigation. We might not realize how important these reactors are until they’re gone.

The post IEA Official Says Green Goals Doomed Without Nuclear appeared first on The American Interest.

California’s Soft Secession

The fantastical push for “CalExit” might be on hold for now, but America’s Left Coast giant is nonetheless beginning to symbolically sever ties with the rest of the United States—a significant provocation that could have wide-reaching consequences down the line. The Sacramento Bee reports that California is banning publicly funded travel to a growing list of red states.

California is restricting publicly funded travel to four more states because of recent laws that leaders here view as discriminatory against gay and transgender people.

All totaled, California now bans most state-funded travel to eight states.

The new additions to California’s restricted travel list are Texas, Alabama, Kentucky and South Dakota.

They join Kansas, Mississippi, North Carolina and Tennessee as states already subjected to the ban.

California Attorney Xavier Becerra announced the new states at a Thursday press conference, where he was joined by representatives from ACLU Northern California and Equality California.

“We will not spend taxpayer dollars in states that discriminate,” Becerra said.

As we noted when California inaugurated this policy, American federalism is based on the agreement that different states can pursue different policies (within Constitutional bounds) while retaining equal status within the union. California’s decision to escalate the culture war with “sanctions” against states with different political orientations represents a direct challenge to America’s federal structure.

This new order could have a major symbolic impact—for example, by making it difficult or impossible for University of California sports teams to compete against the University of Texas. And could lead to retaliatory measures by the targeted red states: They could, for example, up the ante not only by enacting reciprocal travel bans but also by refusing to cooperate with California’s government in criminal investigations, declining to share tax data, or prohibiting companies from selling products to California’s state government. How long before a coalition of liberal states begins to collectively and systematically impose sanctions on conservative ones, or vice versa?

To state the obvious: This has nothing to do with the legitimate democratic debate over the merits of the policies California is trying to sanction in the first place. Maybe some of these policies are reasonable compromises between LGBT rights and religious liberty; maybe others are unacceptable forms of discrimination. These are debates that need to be resolved by the courts, by federal civil rights agencies, and by the voters in those states. California’s brazen offensive dangerously short-circuits this process.

If we accept this precedent—if blue states begin to sanction red states and red states return the favor—then it’s easy to see how the culture war’s tendency to escalate could produce a full-blown constitutional crisis, or worse. We need to stop this before it sets us on a road from which there’s no turning back.

The post California’s Soft Secession appeared first on The American Interest.

F-35s Worth the Hype After All?

After more than its share of trials and tribulations, the F-35 fighter jet is now the envy of the world’s armed forces, says Real Clear Defense:

This week’s performance by the F-35 fighter at the Paris Air Show is a turning point for the world’s most advanced multi-role fighter, demonstrating that even when fully loaded with combat gear, it can out-perform the tactical aircraft of every other country. […]

If you are searching for a metaphor that captures what F-35 delivers to America’s military, consider the example of two prize fighters. The next-generation contender has a stronger punch, a longer reach, and superior situational awareness. But he also has something else that transforms the fight—he is invisible to his adversary. Whatever the other fellow’s training might be, he can’t see his rival to land a punch. So he’s down before the first round is over. That’s what makes the F-35 a game-changing aircraft, the one plane that can keep America’s enemies at bay for another generation.

This praise is hard-earned and bodes well for the ability of the United States and its allies to maintain a technical superiority in fighting capacity. Looking past the issue of cost overruns, Real Clear Defense shows that the F-35 has proven to be a resounding success story on all the key metrics. The plane has not once failed to outmaneuver its rivals in head-to-head showcases like the one that occurred last week, it possesses advanced sensor fusion and networked operations features that have been carefully refined over 16 years of development, and the Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force each have adopted versions of the new aircraft that will upgrade their capabilities dramatically. (One variant, for example, has consistently achieved a kill ratio above 20-to-1 in exercises, and sea trials indicate that the carrier-based variant has “demonstrated exceptional performance” in all theatres where it has been tested.

At a broader level, the development of the F-35 indicates the continued resolve of the United States to carry out lengthy, resource-intensive projects intended to shore up its unmatched military might. Critics, including President Trump, have long cast aspersions on the program for its delays and costs, but those problems are now largely in the past. Demand for the fighters remains high even as their cost is stabilizing, and they have already been deployed to Japan as well as Europe. The F-35 will also be an important addition to America’s aerospace export sector for years to come as more countries are approved to purchase it.

Once again, the United States proves it has the will, know-how, and tenacity not to fight fair.

The post F-35s Worth the Hype After All? appeared first on The American Interest.

Luck, Chance, and Taxes

Success and Luck: Good Fortune and the Myth of Meritocracy

By Robert H. Frank

Princeton University Press, 2017, 208 pp., $26.95

Robert Frank’s recent book, Success and Luck, is an engaging, partly autobiographical account of why and how most Americans underestimate the role of luck in economic success. Frank sees our tendency to overlook the role of luck as a cultural bias that helps explain why we are less likely than Europeans to favor high taxes on the rich and generous benefits for the poor.

Frank also thinks that compressing the distribution of income would make life better for the vast majority of Americans, including most of the rich, because it would strengthen our sense of community and make us treat one another better. He concedes, of course, that higher taxes would leave the rich with less money to spend on private luxuries, such as living rooms with a view of the Golden Gate Bridge or parties at New York’s most expensive restaurants. He argues, however, that the price of most such luxuries would fall if the rich had less money to spend. Meanwhile, the rich would still have more money for luxuries than anyone else, so they would still end up owning most of the homes with great views and eating most of the meals at expensive restaurants.

To assess these arguments we need to be clear about what Frank means by “luck.” The word is a shape-shifter, not only because it means different things to different people, but because it means different things in different contexts to the same person, including Frank. In everyday conversation, however, “good luck” usually refers to an unforeseen event that makes someone better off without requiring commensurate risk or effort. Finding a $20 bill in the street is a standard example. “Bad luck” is a little more complicated. Sometimes it is just the antonym of good luck: an unforeseen event that makes someone worse off, like losing a $20 bill. However, bad luck can also refer to the unpreventable consequences of widely anticipated events. The weather bureau can now predict a hurricane far enough in advance for almost everyone in its path to flee, for example, but homeowners still cannot prevent the hurricane from flattening their beachfront summerhouses. The common thread uniting “good” and “bad” luck is thus that they both involve events beyond our control, which means we do not deserve either credit or blame for them.

The kinds of events that both Frank and others describe as “lucky” are, however, seldom entirely beyond the control of the individuals they affect. In his preface to Success and Luck, for example, Frank quotes at length from an address that Michael Lewis delivered to Princeton’s graduating class in 2012. Lewis described his path to success this way:

One night I was invited to a dinner, where I sat next to the wife of a big shot at a giant Wall Street investment bank called Salomon Brothers. She more or less forced her husband to give me a job. I knew next to nothing about Salomon Brothers. But Salomon Brothers happened to be where Wall Street was being reinvented. . . . When I got there I was assigned, almost arbitrarily, to the very best job in which to observe the growing madness: they turned me into the house expert on derivatives. A year and a half later Salomon was handing me a check for hundreds of thousands of dollars to give advice about derivatives to professional investors.

Not long after Salomon handed Lewis that check he quit his job to write a book, about which he says:

The book I wrote was called Liar’s Poker. It sold a million copies. I was 28 years old. I had a career, a little fame, a small fortune, and a new life narrative. All of a sudden people were telling me that I was born to be a writer. This was absurd. Even I could see that there was another, truer narrative, with luck as its theme. What were the odds of being seated at that table next to that Salomon Brothers lady? Of landing inside the best Wall Street firm from which to write the story of an age? Of landing in the seat with the best view of the business?

Although Lewis ascribes this sequence of events to luck, that description turns out to be overly simple. First, he asks rhetorically what the odds were of his being seated next to the “Salomon Brothers lady.” At least according to Wikipedia, Lewis was seated there at his own request by his cousin, the Baroness Linda Monroe von Stauffenberg, who was on the planning committee for the dinner. Lewis needed a job and hoped that his cousin could help him land one at Salomon by seating him next to the wife of the man who ran Salomon’s London operations. Having a cousin who can seat you next to someone whose husband can give you a job at Salomon Brothers would qualify as “good luck” in the colloquial sense even if Lewis made no such request, but it seems he may have planned the whole thing in advance. The only part of this story that was really beyond his control was the fact that his cousin knew the “Salomon Lady” in the first place. That Lewis then made a favorable impression on both the lady and her husband was Lewis’s own doing.

Salomon’s decision to turn Lewis into an expert on derivatives may, in contrast, have been entirely outside his control. However, the fact that he got a check for “hundreds of thousands of dollars” a year and a half later was probably not luck but a byproduct of his being a quick study who used his skills to sell Salomon’s clients a lot of derivatives.

Lewis also implies, without explicitly saying so, that Liar’s Poker sold a million copies by luck alone. However, the book is both gripping and well written. Gripping, well-written books do not always sell a million copies, but their chances of doing so are a lot better than the chances of a boring, badly written book doing the same. Since some of his subsequent books were also best-sellers, the success of Liar’s Poker cannot have been pure luck.

Lewis’s account has at least two implications. First, he would not have written Liar’s Poker without some lucky accidents, of which the social connection between his cousin Linda and the wife of the big shot at Salomon was probably the most important. Beyond that, the role of luck is less certain. To echo Lewis, what are the odds that if another young man had been seated next to the Salomon Brothers lady she would have insisted that her husband hire him? Or that another young man, having been handed a check for hundreds of thousands of dollars after 18 months at Salomon, would have left to write a book rather than staying to see if subsequent checks got even bigger? Luck was probably a necessary condition for writing Liar’s Poker, but it was certainly not sufficient.

Both Frank and others often use “chance” as a synonym for “luck,” but that usage is often misleading. “Chance” typically refers to events that are fundamentally unpredictable, like winning the state lottery. The path of a hurricane is not pure chance, which is why forecasters can predict it with some accuracy. However, I might describe the fact that the hurricane destroyed your house but not your next-door neighbor’s house as chance, at least if I did not know that your next door neighbor’s house was designed to withstand hurricanes. That said, only a small subset of all “lucky” and “unlucky” events is attributable to chance alone.

The ancient Romans thought the goddess Fortuna had blessed individuals who were consistently lucky, while those who seemed consistently unlucky must have offended some other powerful god. Modern science discourages such thinking by assuming that impersonal causal chains are everywhere, even when we cannot see or understand them. We might therefore expect the spread of modern science to have reduced the frequency with which people attribute events to good or bad luck. We see this tendency reflected even in well-known hokum folk wisdom: “The harder I work the luckier I get.” However, in the early 1990s, when the British psychologist Richard Wiseman and his collaborators asked a large street sample of London shoppers whether they considered themselves lucky, unlucky, or neither, 50 percent said they were lucky, 14 percent said they were unlucky, and only 36 percent said they were neither.1

Despite the fact that Success and Luck is subtitled “Good Fortune and the Myth of Meritocracy,” Frank does not actually think meritocracy is a myth. On the contrary, he argues that big corporations have become steadily more meritocratic in recent decades. By this he means that they try to select their executives based on criteria that both they and their competitors think likely to maximize a firm’s profitability, such as how quickly candidates can master complicated subjects quickly whether they can persuade others that their analysis is correct, and how hard they are likely to work on their employer’s behalf. These criteria may not be very good at identifying the CEO most likely to maximize a firm’s future profits, but most corporations are trying to use the best predictors they can find.

One consequence of meritocracy’s spread has been the growing number of candidates considered for top corporate jobs. Until the 1960s most big American corporations looking for a new CEO considered only white American men who already worked at their firms. Today these firms search all over the globe and often consider candidates who are not American by birth or upbringing. They also consider (and sometimes even hire) women, non-whites, and managers who currently work at other firms. As a result, the number of potential candidates for most top jobs has grown substantially, as has the number of candidates for other high-level jobs.

If nothing else had changed, expanding the number of candidates should have driven down their compensation. However, many big firms have grown even bigger over the past fifty years, and when a firm’s revenue doubles, the value of managers who can add one percentage point to the firm’s profit margin also doubles. Global competition and technical innovation have also made corporate directors less complacent about firms’ ability to prosper simply by continuing to do what they have always done. Taken together, rising firm sizes and anxiety about the future have led big firms to pay whatever it takes to get a CEO who is widely viewed as one of the most competent and forward-looking in the business. As a result, CEO pay at big corporations has risen faster than that of any other occupational group, and the same is probably true for those who rank just below the CEO. That trend has encouraged a growing fraction of the world’s most ambitious university graduates to enter the race for these jobs.

Frank’s explanation for the growing importance of luck follows directly from the growing competition for top jobs:

Chance events are more likely to be decisive in any competition as the number of contestants increases. That’s because winning a competition with a large number of contestants requires that almost everything go right. And that, in turn, means that even when luck counts for only a small part of overall performance, there’s rarely a winner who wasn’t also lucky.

This observation is Frank’s most important contribution to understanding the role of luck in success. It does not imply that any single form of luck has become more important over time, only that as the number of highly qualified candidates grows, the number who meet all the traditional meritocratic requirements is also likely to grow. That will force selection committees to use other criteria as tie-breakers. Those non-meritocratic criteria will often be untested, sometimes unconscious, and sometimes counterproductive.

Frank hopes that by calling attention to the role of luck in success he will convince readers that top executives’ outsized pay packets, while usually traceable partly to their talent and hard work, are also traceable to lucky breaks for which they deserve no special credit. He hopes this realization will make more Americans support raising taxes on the rich and putting the receipts to more productive uses than buying highly rated bottles of wine.

That might happen, but most Americans already think the rich should pay more taxes. The decline in top Federal income tax rates from 91 percent in 1963 to less than 40 percent since 1987 did not derive from popular reluctance to tax the rich heavily. It probably derived mainly from legislators’ growing reliance on paid advertising rather than unpaid volunteers to get re-elected. Few legislators want to appear hostile to their biggest benefactors. Changing public opinion about lucky rich people won’t change that.

Because Frank cares about poverty as well as wealth, I was surprised that he devoted so few pages to the two forms of luck that many social scientists would say have the biggest impact on people’s economic success, namely the DNA they inherit from each of their parents and the physical and social environments in which they grow up. Children inherit half their genes from each of their biological parents, and economically successful parents can usually do more than unsuccessful parents to develop the skills and character traits that facilitate children’s eventual economic success. As a result, children’s earnings are positively correlated with their parents’ earnings at the same age, not just in the United States, but in every other nation for which we have data (although the strength of the correlation varies, of which more below).

The correlation between parents’ and children’s earnings is one measure (though certainly not the only one) of what I will call “familial luck.” By this I mean the luck that flows from having had one set of parents rather than another. Calling children’s social environment a matter of luck may seem misleading to adults who spend endless hours (and dollars) trying to maximize their children’s future opportunities and see others doing the same. To adults, the fact that parents who prosper tend to have children who prosper is a predictable byproduct of parental effort, despite the many exceptions. For a child, however, the fact that other parents can do more for their children than their own parents can do for them is a major discovery. Of course, no one has ever had a choice of parents, and we wouldn’t be us if we did. But from such a child’s viewpoint, at least, his parents’ inability to do as much as many other parents is bad luck.

Most modern democracies try to blunt the effects of familial luck by at least paying lip service, and often a good deal more than that, to the ideal of equal opportunity. This ideal has many possible interpretations, but in politics and the media it usually means that children’s chances of economic success or failure should not depend on their parents’ income, race, or other characteristics. Skeptics argue—correctly in my view—that completely eliminating the correlation between children’s and parents’ earnings is an unrealistic goal, since it would require both abolishing the nuclear family and standardizing children’s genes. However, if we redefine the goal of equalizing opportunity as simply reducing rather than eliminating the current correlation between parents’ income and their children’s income, the experience of other rich nations suggests that the United States could move considerably further in this direction without weakening the family or manipulating the gene pool.

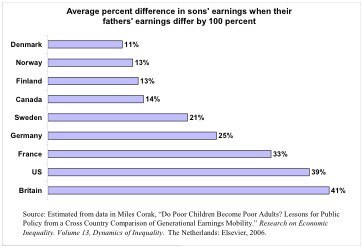

Figure 1 estimates the average earnings gap in nine rich democracies between thirty-year-old sons whose fathers’ earnings differed by a factor of two (100 percent) at age thirty. In Great Britain fathers with earnings that differ by 100 percent have sons whose earnings differ by an average of 41 percent. In the United States the difference is 39 percent. Among Canadian fathers with earnings that differ by 100 percent, however, sons’ earnings differ by an average of only 14 percent. In most of Scandinavia the gap is 11 to 13 percent. France, Germany, and Sweden lie between these extremes. Figure 1 suggests, though it certainly does not prove, that the governments of nations may be able to exercise considerable control over the importance of familial luck, at least if their citizens have the political will to try.

Figure 1 also tells us something about where different kinds of English-speaking adults might want to live. If they expect to be (or already are) near the top of the economic ladder and want to pass along their advantages to their children, they should live in Great Britain or the United States. If they do not expect to be near the top of the economic ladder themselves but want their children to have a fair chance of moving up, they should live in Canada. (I could not find similar data for Australia or New Zealand.) Infants cannot make such arrangements for themselves, of course, so for them being born in, say, the United States rather than Canada is just a matter of luck.

Frank does not discuss familial luck in this book. His original—and stunning—contribution is his analysis of good luck’s role in reaching the top. Demonstrating that as competition for top jobs increases, the odds increase that luck will play some role in one’s chances of success could be a game changer. If Americans are lucky, this argument would reduce opposition to taxing the rich more heavily. Otherwise, it will continue to be true that, as E.B. White put it in a quip that Frank uses as the epigraph for this book, “Luck is not something you can mention in the presence of self-made men.”

1Richard Wiseman, The Luck Factor (Miramax Books, 1993), p. 10.

The post Luck, Chance, and Taxes appeared first on The American Interest.

Peter L. Berger's Blog

- Peter L. Berger's profile

- 227 followers