Peter L. Berger's Blog, page 181

June 6, 2017

Robots Could Block Path out of Poverty

The traditional exit from poverty for poor countries — followed over the decades by Japan, Taiwan and South Korea, among others — is to be the cheap labor for rich nations. But the robotics revolution may be foreclosing that route to the middle class, MIT economist Daron Acemoglu tells Axios. […]

Speaking in his office, Acemoglu said that for seven decades, every fast-growing country has used export-focused manufacturing built on cheap labor to undercut foreign competition.But, said Acemoglu: “If robotics makes labor uncompetitive in these lowest-skill and sometimes in the medium-skill occupations, this development path would be closed to the next group of developing countries and would make the further development of countries, such as China or Vietnam, also very difficult.”

In particular, this means that Africa may miss out on the benefits of industrialization if robots replace cheap human labor. That is not a terrible thing in and of itself—life in a textile sweatshop is hardly the acme of human existence—but it leaves the question open of how the hundreds of millions of Africans heading into the cities from the farms will be able to make a living once they get there.

It also could well mean that the Arab world will never escape from its current “oil or nothing” economic trap. And the economic shock waves caused by these effects will certainly come home to the U.S., quite apart from the disruptions robots will bring to our own manufacturing and service sectors.

The idea that technological progress brings peace and prosperity is one that Americans are instinctively inclined to believe, and in the very long run it could be true. But the bumps in the road can be ferocious: without the amazing invention of the cotton gin, after all, slavery would likely have died out peacefully in the United States.

June 5, 2017

Captured Carbon Is Powering U.S. Oil

A Swiss company made headlines last week when it began operation of what it’s calling the first commercial carbon capture plant. Commercially viable carbon capture systems are something of a silver bullet for climate mitigation efforts, as they would give us a way to reduce atmospheric concentrations of the greenhouse gas that’s driving surface temperatures up. But capturing that carbon is only half of that potential solution—the other half involves what you actually do with the carbon dioxide. Here in the United States, companies are using captured CO2 to help increase production yields in conventional oil wells. Reuters reports:

The drilling method harnesses the carbon dioxide produced during the extraction of oil or from power plants, and forces it back into the fields. That boosts the pressure underground and drives more oil to the surface. […]

[Enhanced oil recovery] could extend by decades the producing life of hundreds more wells, increasing oil supply which would be a drag on prices. To date, the technique has been employed only at conventional oilfields, rather than on shale deposits. Some firms are studying how to put the technique to work in shale drilling, too.

If ever there was a win-win, this would seem to be it. CO2-enabled enhanced oil recovery (EOR) throws a bone to environmentalists and oil boosters alike, and to-date here in the U.S. it’s only been used in conventional oil fields. As the technology matures, drillers will be able to deploy it in shale fields in the coming years and reap significant rewards for their efforts.

Greens’ first instinct will be to turn their noses up at this wedding of fossil fuel development and clean tech, but this is a symbiotic relationship that can benefit both industries. For carbon capture plants to scale up (and build on the momentum of last week’s announcement in Switzerland), they’ll need to show that they’re capable of turning a profit. If that captured carbon can be used to increase oil and gas output, industry will pay for it, and in so doing give valuable financial support to a moonshot eco-solution that has struggled to prove itself viable.

The shale boom has already lowered American emissions by making natural gas a cheaper option than coal. Its next green accolade could soon be its creation of a market for captured carbon.

Ratings Agency Calls Pension Returns Into Question

A major ratings agency has soured on the ability of state and local pension funds to achieve the rate of return they will need to stay solvent without benefit cuts. Pensions & Investments reports:

Fitch Ratings will now discount U.S. public pension plan liabilities at a 6% investment return assumption, down from the current 7%, according to a news release from the ratings agency.

The ratings agency released the new updated U.S. public finance tax-supported rating criteria on Wednesday.

“U.S. growth has been slower and more incremental over the current economic expansion than over longer time horizons. There is little evidence to suggest the economy will accelerate to previous levels of growth in the near term. Fitch believes that pensions will be hard-pressed to achieve their long-term growth expectations in the current economic context,” said Douglas Offerman, senior director at Fitch Ratings, in the news release.

Many funds currently expect returns in the seven to eight percent range. Fitch’s downgrade could increase pressure on funds to reduce their expected return. This in turn will require governments to choose between either reducing benefits—setting the stage for a major battle with public sector unions—and increasing state contributions—requiring either tax hikes or cuts to public services like education and infrastructure.

California’s pension fund, for example, recently cut its expected return from 7.5 percent to 7.375 percent. Even this modest reduction has put the squeeze on many local governments; going all the way down to 6 percent would require huge increases in contributions that would force many localities into bankruptcy.

The crisis of public finance at the state and local level remains an under-covered story with potentially far-reaching consequences. And without a clear path for reform, the vise is only getting tighter.

Breathing Room for the Kremlin

Pity the poor modern historian, who has to explain the seemingly illogical logic of Russia’s trajectory, which stands in defiance of all settled knowledge about the rise and fall of states. Russia presents us with the bizarre, albeit fascinating, case of a state that has found a way to survive despite having exhausted its systemic resources and lost its historical perspective. Just consider: The Russian system, despite having rejected all the key principles of modernity, not only continues to limp ahead with its personalized power construct; it has also succeeded in shaking the foundations of global order and creating a permanent sense of suspense, to which powerful actors have no choice but to react. This system in decline manages to unsettle the established order not because it has a unique ability to break china (a capacity which is often exaggerated), but because the West can’t decide how to deal with it and fears what might happen if this system unravels.

Putin the Winner?

Today, having failed to find a workable solution for the post-Crimea situation, and bogged down by its own problems, the West seems poised to drop its “liberal world order” mantras. Ironically, it is the U.S. President Trump who is now playing the Terminator and has delivered the liberal world order a crushing blow. Trump’s recent trip to Europe for the NATO and G-7 summits, where he openly berated the European allies and showed disdain for Transatlantic dogma, looks like something taken straight out of Putin’s script for undermining Western unity. Chancellor Merkel’s grim conclusion that Europe can’t any longer rely on others and has to take its fate into its own hands sounds like the realization of a dream that even the Kremlin’s inhabitants hardly thought was possible.

For those who like a simplified black and white canvas, what we are now witnessing is without doubt a portrait of “Vlad the Victorious”—especially when one watches how Russia has become a powerful factor in American political life, threatening to delegitimize the U.S. presidency. Who would doubt today Russia’s ability for global mischief? And who would doubt that Russians have to be proud of their prowess? Even the usually shrewd David Ignatius has been confounded; after talking to Russian officials and analysts he concluded that they “are flattered that their country is seen as a powerful threat.”

It depends who you are talking to and on the ability of the Western observer to decipher the Russian narrative and to confront it with reality. Meanwhile, even mainstream Russian analysts watching the American political scene have been forced to admit, “Russia can’t get anything good in this situation” (Fiodor Lukianov). As for the cheerful moods of the Russian audience at the recent Russian Economic Forum in St. Petersburg, the Russian Davos, where Putin’s every joke was applauded, this behavior was not a reflection of self-assuredness and pride in their victory over the West but the usual game of pretending amidst growing uncertainty and consternation.

Indeed, if the Kremlin feels it commands the show, why then did President Putin allow the newly elected Emmanuel Macron to use him to project his own power at Putin’s expense—and even to humiliate him to his face, shocking the Russian public at home? This is definitely not Putin’s aggressive style. And why has the Kremlin switched off the anti-American rhetoric, offering instead an olive branch and inviting Washington to discuss the two sides’ points of contention? Isn’t it unusual for a winner to refuse to use his advantage to press for further expansion and geopolitical gains? Anyway, there are signs that the Kremlin, despite all its litanies to the contrary, is perplexed by the unravelling of the U.S.-led global order, which was in retrospect so comfortable for Russia.

To be sure, the Trump presidency has undermined certain policy mechanisms the Kremlin has successfully deployed up to now. No longer can Putin relish his role as the “Tsar of Unpredictability,” which limits the number of tools in the Kremlin’s kit. The Kremlin can be unpredictable only when it’s sure it knows the rules of the game and how its Western partners/ competitors will react. Putin has always been trying to determine the precise location of the “red line,” beyond which lie unpleasant consequences for Russia. True, he made a mistake with the Crimea annexation, which he evidently believed the West would accept with the same complacency it had demonstrated during the Russo-Georgian war. This time, however, the West was forced to react, albeit in such a way as not to corner Russia. But Putin’s mistake in this case was inevitable; the Russian leader was trapped by the two conflicting logics of the personalized system’s survival plan: the need to preserve Great Power status and the need to exploit the Western resources.

At first the Kremlin may have been happy with Trump’s affinity for Putin and his longing for partnership with Moscow. But the Russian political elite was unprepared for the anti-Russian consensus that has emerged in Washington and become a source of American domestic infighting. Now, when Trump’s every move toward Russia has the potential to undermine both the U.S.-Russian relationship and his presidency too, the Kremlin is at a loss as to how to deal with this toxicity, which promises far-reaching and still uncertain ramifications.

Putin is hardly happy to see that, instead of angling toward a U.S.-Russian “bi-polarity” (the achievement of which has been the core premise of Kremlin policy for decades, whether such “bi-polarity” is based on cooperation or mutual hostility), Trump is dancing with China. As if to add insult to injury, it is China, not Russia, that is filling the void left by U.S. retrenchment in Europe. The Europeans will have their summit with Beijing, not with Moscow.

An “Ignore Russia” approach on the West’s part would be a most painful blow to the Kremlin’s Great Power strategy, which is based on a model of “being with the West while being against the West.” This calls for a response that forces the world to focus on Russia again. However, the Kremlin is not eager to undertake actions that could bring its isolation. Putin definitely did not enjoy having breakfast alone during the 2014 G-20 summit in Brisbane, Australia. Moscow’s dilemma is how to once again merit front-page headlines, above the fold, but without going so far as to provoke unwanted or excessive confrontation.

The Kremlin, having expected the United States under Trump to live up to the “America First” slogan of retrenchment, has to be even more frustrated. Instead, Trump is promising a policy that Stephen Sestanovich has characterized as “kick-ass confrontation” and a “hopped-up version of foreign policy activism.” This is not the old-fashioned U.S. isolationism Moscow had hoped for.

Let’s add to this list of disappointments for the Kremlin: Trump’s brash demeanor and his understanding of transactional relationships as the guarantee of his gains. This is hardly a guarantee of a friendly personal relationship with Putin.

Today Trumpian America is forcing the Kremlin to revise its survival strategy. No more recklessness or macho brutality to test American patience! Caution and caution again are the orders of the day. Yes, sometimes Russian fighters and bombers will skirt along the NATO coast line—but how else to demonstrate that the Bear is not asleep! Kremlin insiders have taken the psychological measure of President Trump and understand how he differs from President Obama (indeed, one can easily imagine a degree of nostalgia in the Kremlin for the Obama years). The Kremlin’s new problem is now this: If Moscow has to restrain its international bullying, what other means does it have on hand to compensate for its shrinking domestic resources? If it is to try engagement with the West, it must avoid sending the Russian domestic audience any signal that the Kremlin is backtracking because it is afraid of how the loose cannon in the White House might react.

A New Chance for the Kremlin

But just when the Kremlin seemed stumped by this new puzzle, along came fortune to show them a solution. Secretary Tillerson’s May foreign policy speech defining U.S. priorities was surely seen as a balm for the Russian side. “We really have to understand, in each country or region of the world that we’re dealing with, what are our national security interests, what are our economic prosperity interests, and then as we can advocate and advance our values, we should,” he said. Remarking upon Tillerson’s statement, Eliot A. Cohen wrote that the Secretary’s idea of foreign policy is that “American interests and American values are two separate things, the first mandatory, the second optional.” One could almost hear the sighs of relief from within the Kremlin. For the United States to play down democracy and human rights issues is a gift for the Russian authorities. With Trump’s abandonment of traditional American democracy rhetoric, Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel remains the only Western leader who still continues to preach Western values to Putin. But without American artillery to back it, Merkel’s lecturing is little more than the buzz of a fly, to be brushed away as Putin did during his recent meeting with the German Chancellor in Sochi. The American change in message means Moscow can finally stop bothering about democracy promotion and “regime change.” This opens a new opportunity for the Kremlin to push things in the international arena a step farther, toward consideration of any democracy promotion effort as a threat to global security and economic prosperity.

Thus Trump has created not just hurdles for the Kremlin but new opportunities too. The fact that even those whom the Kremlin has considered “Russophobes,” such as the late Zbigniew Brzezinski, have proposed the idea of a tripartite “concert” of great powers (America, China, and Russia) as the guarantor of global stability is viewed as a promising trend by the Russian political elite. This “Big Troika” will save the world order, sing Russian pundits, who have already begun to talk about how to secure the right “balance” between the three members. Russia needs to be an equal partner and must demand respect for “ideological and political pluralism,” they insist—which means respect for anti-Western principles, of course. Even more encouraging for the Russian elite is Kissinger’s line, “Let’s reconcile our necessities with their objectives.” How sweet this music is to Kremlin ears!

Meanwhile, American pundits have been offering their recipes for getting out of this mess. Let’s look at their intellectual efforts. Are there any new thoughts? One can already begin to hear a familiar song, “The United States needs a new grand strategy for Russia”; “the U.S. needs a new strategic imperative.” To be sure, we hear such calls at the beginning of every new American presidency. Upon close examination, the “new grand strategy” looks very much like the old one but without the usual lip service paid to values: Pure pragmatism without any attempt to even imitate concern for values. We should forget about the ideological dimension and Russia’s domestic developments, and pay attention only to Russia’s external behavior, say the “new pragmatists.” Doesn’t all this sound familiar? I recall that President Obama also pursued a policy of “de-linkage,” but it did not save his reset. On the other hand, a non-sentimental, business-like pragmatism could be better for one reason: It would not distract or confuse us with empty rhetoric.

The American “Russia hands” eager to fit Trumpian moods try to persuade us that the postmodern fuzziness about norms and principles that has emerged in the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union is the best international environment we can hope for. They argue that we should stop viewing the world through dichotomous lenses: black or white, democratic or authoritarian, weak or strong, war or peace, partners or enemies. Rather, we should endorse ambiguity, the world of “liquidity” (in Zygmunt Bauman words), with its constantly changing colors and flavors. But what, then, has triggered the current Western confusion about its trajectory if it is not the past few decades of postmodern fuzziness, with its world full of “grays.”

Let’s “manage” global risks without trying to resolve our problems, say the new pragmatists. One could give credit to their courageous admission of their failure to find a response to these new challenges (admission of failure is after all the first step on the road to progress). Managing postmodern liquidity seems like a readiness to swim with the tide—but in what direction? Rejecting a values-based foreign policy means shifting toward non-stop tactical maneuvering; whereas strategy would be about attempting to answer the question, “So what are we going to do tonight?” Indeed this looks very much like an incarnation of the famous German Socialist Edward Bernstein’s motto that movement is everything and the goal nothing. And where will this take the world?

The prescriptions the new pragmatists offer do not seem so bracing or fresh either. They usually fit into two categories. The first category are calls to create (or expand) channels of communication between Russia and the United States. Indeed, it is almost always useful to talk. But then one must ask why the multiplication of communication channels during President Obama’s reset within the framework of the U.S.-Russia bilateral presidential commission failed to prevent rapid cooling of relations? Similarly, suggestions to appoint “influential political officials” from both sides of the aisle, along with respected experts (respected by whom?) to conduct the dialogue, are the usual supplements to this “channels” idea. One can’t avoid impression that proponents of these adventures are interested more in their own roles in them.

The second category of pragmatist prescription is the old formula of “contain/cooperate,” sometimes disguised under some novel way of saying “a mix of competition and cooperation.” True, both Russia and America have to continue to search for more efficient models of mutual containment and dialogue about areas ripe for cooperation. But why has this search failed thus far? We might also raise another question here: Why have all these attempts not just failed to stimulate Russia’s modernization but on the contrary helped the obsolete System to gain resilience? Any thought on that among those who promote the “containment/cooperation” formula would be appreciated. Moreover, “containment/cooperation” policy inevitably turns into an endless bargaining session over the tactical interests of both sides, and the Kremlin (credit where credit is due) has always been more skillful in this process.

Perhaps the most hilarious of U.S. expert proposals is the idea of rejecting both confrontation and appeasement in favor of “charting a middle path,” which means “both seeking ways to cooperate with Moscow and pushing back against it without sleepwalking into a collision.” But how technically could this be done? How to pursue “a middle path” between confrontation and appeasement? Explanations, please!

Moscow’s Bargaining Terms

I must remind the new pragmatists about the preconditions for Moscow’s readiness to engage in their preferred model of bargaining. First, America would have to accept the Kremlin’s preference for “linkage” over “compartmentalization” of problems. This means accepting exchanges like cooperation in Syria for endorsement of the Kremlin’s view of the Minsk agreements; or trading an end to Russian sabre rattling close to NATO borders in exchange for sanctions abrogation; and so forth. In short: Bargaining means an exchange of concessions!

Second, Washington has to agree to Russia’s right to interpret international principles and norms as it sees fit, and to accept the Russian understanding of the international and domestic legal order. This includes the right to impose the Kremlin’s perception of international legal order (remember Carl Schmitt, the famous German political theorist, who justified Nazi Germany’s foreign policy?). Thus this is not another Yalta formula; this is a new formula for survival based not on following rules of the game accepted by all partners (which is what Yalta was about) but on the right to circumvent them.

Let’s see how the bargaining process could affect the Russo-Ukrainian conflict, which is the most serious stumbling block for re-engaging Russia. Moscow has certainly wearied of the conflict and wishes to find a way out. No doubt about it. But Moscow can’t do it without major concessions: Western recognition of limits to Ukraine’s sovereignty and of Russia’s right to view that country as falling within its area of “interests” (some pundits define it in a more exquisite form: the U.S. “should seek Russia’s consent to pursue their interests in Eurasia”)—a precedent that, once established, may provoke further chains of events undermining the global status quo. Will America agree to this demand? It looks that the new pragmatists offer a less radical proposition: following an “ambiguity” approach that favors process over result, management of the problem over a solution. This would mean that the Donbass bloodshed will continue indefinitely. But what a chance to experiment with “management”!

I wonder whether Rex Tillerson understands the Kremlin’s formula for bargaining as he prepares his behind-the-scenes Ukrainian initiative. And what will his motivations be for that: to normalize relations with the Kremlin? As Josh Rogin writes, “Ukraine is where Trump’s so far thwarted plan to improve U.S.-Russia relations can be kick-started.” If this is the plan, it would mean throwing Ukraine under the bus because president Putin is not ready to backtrack on his understanding of the Minsk accord that he has demonstrated not once.

The attempt to build a new “grand strategy” often just looks like an effort to use new-sounding terminology to mask a fundamental lack of new ideas. One could also view it as an example of how Western rationality is totally out of sync with the Kremlin’s rationality. Or is it simply a Western failure to understand Russia’s survival logic? Take, for instance, the idea favored by some American experts of turning Russia into a tool to help contain China’s rise. Come on! Do they really believe that the Kremlin is so naive and stupid as to allow itself to be used against China? This is an insult to the Kremlin’s intelligence.

But what about bargaining on Syria? It looks like the Kremlin really wants to find an exit from this imbroglio. But what reward is America prepared to give Moscow for its cooperation? Some have also suggested the Arctic as a zone of possible U.S.-Russia dialogue. But look: Russia has already guaranteed its military and industrial presence there, and Moscow feels it has the right to dominate the agenda. I am not sure Moscow is ready to exploit Arctic commercial opportunities on American terms. Is Washington ready to be a junior partner to Moscow?

The current American shift toward non-sentimental pragmatism and readiness for deal-making has indeed opened up space for re-engaging with Russia, and the Kremlin has to welcome such an opportunity. Today both Merkel and Macron are also talking about normalizing the relationship with Russia. (Macron even spoke about his wish to “strengthen partnership with Russia” in the struggle with terrorism), apparently hoping to pursue it on Europe’s terms. But what are those terms? In any case, Putin is patiently waiting for the process to start, and nobody is a match for the Kremlin in operational tactics and resolve.

Re-engagement allows the Russian ruling team to continue regulate its anti-Americanism and anti-Western propaganda for domestic purposes (switching it on and off as needed) and at the same time allows it to restore one of the most important drivers of the Russian system’s survival: the exploitation of Western resources. However, while this approach will help to preserve the Russian personalized power system, it will not modernize Russia. The supporters of this approach either have not considered these implications or are perfectly aware of them but have chosen to ignore them. Either explanation is a grim commentary on their ability for strategic thinking.

Mattis to Asia: Rest Assured, and Bear With Us

Defense Secretary Mattis took the stage in Singapore this weekend for a highly-anticipated speech at the Shangri-La Summit to articulate the Trump administration’s vision for the Asia-Pacific. North Korea and China were high on the agenda, as Reuters reports:

“The Trump administration is encouraged by China’s renewed commitment to work with the international community toward denuclearization,” Mattis said.

“Ultimately, we believe China will come to recognize North Korea as a strategic liability, not an asset.”

However, Mattis said seeking China’s cooperation on North Korea did not mean Washington would not challenge Beijing’s activities in the South China Sea.

Mattis sent three clear messages here that align with Trump’s early moves in Asia. First, North Korea is clearly the top priority. In Singapore, Mattis explicitly echoed Vice President Pence in calling Pyongyang “the most urgent and dangerous threat to peace and security in the Asia-Pacific.” Second, the Administration is exploring ways to peel China away from North Korea, a hope that has long been central to Trump’s posture toward Beijing. And third, soliciting China’s cooperation against Pyongyang does not mean allowing Beijing a free hand in the South China Sea, a message underlined by the Navy’s recent freedom-of-navigation operation there. On those three counts, then—and in his later emphasis on counter-terrorism and allied burden-sharing—Mattis convincingly articulated the contours of Trump’s emerging Asia policy.

Elsewhere, though, Mattis’s talking points ran up against both Trump’s own instincts and a skeptical audience. The speech was peppered with paeans to the “international rules-based order,” affirmations of allies, a call for deeper engagement with institutions like ASEAN, and even an encouragement for Thailand to return to democracy. The tension between Mattis’s rhetoric and Trump’s comparatively transactional views was not lost on the audience, who expressed doubts about Trump’s commitment to those same principles. At times, Mattis’s responses seemed to implicitly rebuke his own boss. “Like it or not, we are a part of the world,” he said when asked whether Trump’s actions would destabilize the U.S.-led global order. Soon after, he invoked Winston Churchill: “Bear with us, once we’ve exhausted all possible alternatives, the Americans will do the right thing.”

It may be that the tension between Trump and Mattis is more rhetorical than practical. The Defense Department, after all, has been given a long leash to operate under Trump, and its recent moves in the South China Sea and Sea of Japan certainly counter the narrative of disengagement. But the skeptical reception to Mattis’s speech suggests that allies still question whether he can speak for a president known for routinely undercutting his own subordinates and indulging his deeply-held transactional instincts. From his abrupt withdrawals from Paris and TPP to his grandstanding over THAAD payments with Seoul, Trump has given allies plenty of reason to question his commitment. It will take more than one skillful speech to dispel the doubts.

Gulf States Cut Ties with Qatar

Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, Egypt, Yemen and the Maldives cut off relations with Qatar overnight in a significant escalation of the tensions in the region. As the BBC reports:

A number of Arab countries including Saudi Arabia and Egypt have cut diplomatic ties with Qatar, accusing it of destabilising the region.

They say Qatar backs militant groups including so-called Islamic State (IS) and al-Qaeda, which Qatar denies.

The Saudi state news agency SPA said Riyadh had closed its borders, severing land, sea and air contact with the tiny peninsula of oil-rich Qatar.

Qatar called the decision “unjustified” and with “no basis in fact”.

This latest crisis has been brewing since the apparent hacking of the Qatar News Agency’s twitter feed last week, when a pro-Iran statement was attributed to Qatar’s Emir Tamim. In their official announcement, the Saudis cited Qatari support for the Muslim Brotherhood, ISIS, and Iranian-backed militants in Saudi’s Eastern Province.

While Saudi and the UAE have cut ties with Qatar before, the newly imposed measures are harsher and more clearly designed to bring Qatar to heel. The suspension of flights will threaten Qatar’s role as a major regional transportation hub—some 30 flights, now canceled, operate between Dubai and Doha daily. The closure of the land border has prompted a run on supermarkets. Oil prices have fallen as speculators fear that the moves could undo the OPEC deal on production cuts.

The claims made against Qatar are a mix of long-standing grievances, facts, and likely fiction. While Qatar stands alone among the GCC states in its degree of support for Hamas and the Muslim Brotherhood, the claim that the Qataris are supporting Yemen’s Houthis seems implausible given Qatar’s troop deployment as part of the Saudi-led anti-Houthi coalition.

Emails leaked to the Huffington Post last week show the efforts of the UAE’s ambassador to influence U.S. thinking on the Qatari question. It would be unsurprising if the UAE and Saudi were not privately offering inducements to close the U.S. base at Al Udeid.

The Trump administration has so far been circumspect in its comments, with Secretaries Mattis and Tillerson saying only that they don’t think it will impact operations against ISIS. While true in a military sense, it’s difficult to see how the crisis won’t undermine the call President Trump made in Riyadh for a unified front against terrorism and Iran.

Qatar’s regional role is complicated. While hosting CENTCOM, Qatar is also home to the sole foreign diplomatic facility of the Taliban. They offer safe haven to Hamas and a platform for their leadership on Al Jazeera. While putting on a friendly face as host of the 2022 World Cup, they fund violent Islamists across the region. Saudi, the UAE and Egypt have clearly had enough. Whether this will be enough pressure to get Qatar to change course remains to be seen.

The Six Day and Fifty Years War

The most important lesson of the June 1967 Arab-Israeli war is that there is no such thing as a clean war. That war was very short and stunningly decisive militarily; it has been anything but that politically. From the Israeli point of view, military victory solved some serious near-term challenges, but at the cost of generating or exacerbating a host of longer-term ones—some of which may have come along anyway, some not, some of which may have been averted (or worsened) had Israeli postwar policy been different—and we cannot know for certain which are which. To ask whether what has transpired after the war “had to be that way” constitutes an aspiration to levitate the philosopher’s stone.

At any rate, of the war’s many consequences, three stand out as pre-eminent. First, major wars change the societies that fight and endure their consequences. The Six Day War changed the political, social-psychological, and, in at least one key case, demographic balances within all the participating states and a few others besides, with multiple and varying secondary and tertiary effects over the years. Second, despite the war’s after-optic of a smashing Arab loss, it was the best thing that ever happened to the Palestinian national movement. And third, the war catalyzed a redirection of U.S. Cold War policy in the Middle East (and arguably beyond) from one teetering on the edge of generic failure to one of significant success.

At this fiftieth “jubilee” anniversary of the war, buckets of ink will inevitably be spilled mooting and booting about such questions and many others; a lot already has been, and I am not reluctant to add to the bucket count.1 But before doing so, we all need to take a deep breath to inhale as much humility as we can—to remind ourselves what exactly we are doing and what we cannot do when we exhume moldering chunks of anniversarial history for reexamination.

Shiny Anniversaries

We are so very attracted to anniversaries in the long parade of political history. We love to draw clear lessons from them, if we can—and if we can’t some others will claim to do so anyway. We are also attracted to thinking in terms of parsimonious eras with sharp lines of delineation between them; anniversaries of turning or tipping points help us mightily to draw such lines—which is precisely why we call them epochal. Wars, mostly hot but occasionally cold, figure centrally in the pantheon of such points.

The June 1967 Arab-Israeli War is all but universally considered to be epochal in this sense, so the recent ink flow is no wonder as journalists, scholars, memoirists, and others look for lessons and insight as to how those supposed sharp lines that divide eras were drawn. The subtitle of a new book furnishes a case in point: “The Breaking of the Middle East.”2

There is a problem here—at least one, arguably more than one. Without yet having read this book, I cannot say for sure that this subtitle is not magnificently meaningful. But I can say for sure that it puzzles me. What does it mean to say that a region of the world is “broken”? Does it imply that before the 1967 Middle East War the region was somehow whole, a description that implies adjectives such as peaceful, stable, and nestled in the warm logic of a benign cosmos; and suggests that regional wholeness also meant that its state or regime units were seen as legitimate by their own populations and by other states and regimes? So on June 4, 1967 the Middle East was whole, and by June 11 it was well on its way to being broken?

All of which is to say that the penchant for reposing great significance in anniversaries is often distortive, because for many it reinforces the right-angled sureties and sharp distinctions—and presumed causal chains leading into our own time bearing those precious, sought-after lessons—that historical reality rarely abides. Only by rounding off the ragged edges, usually with a rasp composed of our contemporary concerns and convictions unselfconsciously pointed backwards, can such artificial categories be devised. Ambiguity annoys most people, and so they go to some lengths to duck it, in the case of getting arms around history by generating categories, boxes, and labels into which to shove obdurate facts. History, meanwhile, remains the sprawling entropic mess it has always been and will always remain.

To employ the anti-ambiguity rasp presupposes, too, that the craftsman commands cause and effect. We can, after all, only simplify a reality we presume to understand in its detail. When it comes to the Six Day War, that means presuming to know how it started and why, how it ended and why, and what the war led to thereafter in an array of categories: how the postwar geopolitical trajectory of the core Middle Eastern region and its periphery spilled forth; how the region’s relationship to the key Cold War superpower protagonists shifted; the war’s impact on the domestic political cultures of participants and near-onlookers; and more besides.

The problem here is that we know with confidence only some of these causal skeins, and, what is more (or actually less), some of what we know has not stayed constant over the past half century. At one point, say thirty years ago, we thought we understood the Soviet government’s role in fomenting the crisis by sending false reports of events in Syria to the Egyptian leadership; after the Soviet archive opened in the early 1990s, consensus on that point has weakened as revisionist interpretations have come forth.3 Nasser’s moving-target motives at various points in the crisis leading to war seemed clear for a time, until they no longer quite did. Several more examples of elusive once-truths could be cited.

Alas, every seminal event has a pre-context and a post-context: the convolutions of historical reality that give rise to an event and its causal afterflow. The further we get from the event, the greater the still-expanding post-context overshadows the pre-context, because we can see, for example, how various things turned out in 2017 in a way we could not have in, say, 1987. But so much else has happened that must, of necessity, dilute any construction of direct or preponderant causality.

Thus, did the war push Israeli society into becoming more religious, as many have claimed? Did it help shift Israeli politics to the Right by transforming the relationship of Orthodox Judaism to Zionism, leading Orthodox Israelis to engage on many political issues to which they had been formerly aloof? Or was that a deeper social-demographic trend that would have happened anyway, if differently, war or no war? So we face a paradox: the richer the post-context becomes for any epochal event, the poorer becomes our ability to isolate its downstream impact. As already suggested, we often enough make up for that poverty by exiling natural ambiguity before the demands of our current questions or biases. That is how we predict the past.

Scholars do try to isolate causal threads, of course, but differently because intellectual business models, so to speak, differ. Historians tend to seek out particularities; political scientists tend to search for general rules. Historians like their rocks fresh and jagged; political scientists like theirs rounded by patterns that flow through time. Each to their own intellectual aesthetic.

And the rest of us? How do we chase truth in history? Consider that if you pick up a history book and a memoir old enough to serve as an adjunct to it, you will have in your hands two different perspectives on the political world. An international political history of the 1930s written in the 2010s will take a passage of reality—say about the British, French, and American reaction to the 1935 Italian aggression against Ethiopia—and might spend two sentences or perhaps a paragraph on it. A memoir written in the 1950s by someone actually involved in debating and shaping that reaction will read very differently, recalling details, sideways connections to other issues, and nuances of policies and personalities bound to be lost in a general text if it aspires to be less than 10,000 pages long. In a history book such a mid-level event is likely to be framed as a consequence of larger forces that were leading to more portentous happenings (say, World War II); in a memoir it is more likely to be framed as both illustration of a synthetic historical moment, akin to a zeitgeist that is fully felt but is recalcitrant to reductionist analysis, and partial cause of what came after. Which do we read; which do we trust?

The answer is both, and wholly neither. How will the Six Day War figure in history books fifty years from now? There’s no way to know, because it will depend at least as much on what happens between now and then as it will on what happened in May and June 1967. But one thing we do know: As the post-context of the war doubles, the thinness and sameness of the description will grow, and be of little help in understanding how the main actors involved saw their circumstances. It will lose a sense of human verisimilitude. Details invariably give way to theme, and narratives grow shorter even as their truth claims grow larger. The thickness of memoirs will retain that sense of human verisimilitude. But what they provide in terms of broader context may suffer from too narrow an authorial aperture, and perhaps a bad memory in service to ego protection, if not other incidental causes of inaccuracy. As with many aspects of life, intellectual and otherwise, tradeoffs spite us in our search for clarity.

The point of all this? Anniversaries are shiny. They attract a lot of attention, much of it self-interested and sentimental enough to lure some people into excessive simplifications if not outright simplemindedness. If someone will bait the hook, someone else will swallow it. We witnessed exactly such a spectacle not long ago at the 100th anniversary of Sykes-Picot, and we’ll see it again a few months hence with the 100th anniversary of the Balfour Declaration.4 But as Max Frankel once said, “simplemindedness is not a handicap in the competition of social ideas”—or, he might have added, historical interpretations. If it gets you on TV talk shows to sell your book, no form of simplification is liable to remain out of bounds these days. After all, what is fake history if not a collection of aged fake news?

Shining On

Never mind all that: I want people to read this essay, so rest assured that I know what happened and why, and what it all means even down to today. And now that I have donned sequins and glitter, I can be almost as brief and punchy as I am shiny, as is the current custom.

What did the war mean for the region? Plenty. It proved to remaining doubters that the Arabs could not destroy Israel by conventional force of arms. It helped establish Israel’s permanence in the eyes of its adversaries, the world at large, and, to an extent, in the eyes of its own people. That changed Israel’s domestic political culture. It no longer felt to the same extent like a pressure-cooking society under constant siege, and that, along with demographic and other subterranean social trends, ironically loosened the political grip of Israel’s founding generation of leaders, and the Labor Party. Less than a decade after the war Revisionist Zionists came to power for the first time, and now, fifty years later, Israel has the most rightwing government in its history. Did the Six Day War directly cause that? Of course not; but it was one of many factors that steered Israeli politics toward its current circumstances.

The war also began the occupation, first of Golan, the West Bank, and Gaza—in time a bit less of Golan and not of Gaza at all. If you had told typical Israelis in the summer of 1967 that fifty years later the West Bank would still be essentially occupied, neither traded for peace nor annexed, they would have thought you mad or joking. Israel as an independent state was 19 years and a few weeks old on June 5, 1967. The twentieth anniversary of the war in 1987 was about the midpoint of Israel’s modern history, half within-the-Green-Line and half beyond it. Now vastly more of Israel’s history has passed with the occupation as a part of it. Many more Israelis today cannot remember Israel in its pre-June 1967 borders than can—and that includes the Arabs citizens of the state as well as their ethno-linguistic kin living in the West Bank and Gaza.

In Israel there is a huge open debate, and a constant more private discussion beneath it, as to how the occupation has changed the nature of Israeli society. It is a difficult debate to set premises for, because in fifty years a lot is going to change in any modern society, occupation or no occupation. My view, like that of most Israelis I know, is that the occupation has been significantly corrosive of many Israeli institutions. They would like the occupation to end if it could be ended safely; but increasingly most agree that it can’t be, at least anytime soon. The remarkable fact is that, considering the circumstances, the damage to morale and heart, beyond institutions, has not been even worse. Israel’s moral realism has proved resilient. But the damage has not been slight, and of course it is ongoing.

As for the Arabs, the war crushed the pretentions of Arab Socialism and of Gamal Abdel Nasser. Within what the late Malcolm Kerr called “the Arab Cold War” it played in favor of the Arab monarchies against the military-ruled republics and hence generally in favor of the West; but it did not guarantee the safety of monarchical rule everywhere: Just 27 months later the Sanusi kingdom in Libya fell to a young army colonel named Muamar Qadaffi. None of the defeated Arab states lost its leader right away: not Nasser in Egypt, or King Hussein in Jordan, or Nurredin al-Atassi in Syria. But by the late autumn of 1970 Nasser was dead and al-Atassi had been displaced by Hafez al-Assad. Rulers also rolled in Iraq, and the very next year, with the British withdrawal from East of Suez, the United Arab Emirates came into being against it own will.

The war, therefore, was one element—more important in some places than others—in a general roiling of Arab politics (and I haven’t even mentioned stability-challenged zones like Yemen and Sudan), those politics being pre-embedded, so to speak, in generically weak states (again, some more than others).5 Not that Arab politics was an oasis of serenity before June 1967 either, as a glance at post-independence Syrian history will show. Indeed, the contention that the Six Day War, by hollowing out the pretensions of secular Arab nationalism for all to see, presaged the “return of Islam” with which we and many others struggle today is both true and overstated—in other words, too shiny. The frailties of secular nationalism among the Arab states preceded the war and would have multiplied on account of any number and kind of failures to come, war or no war.

In any event, the political impact of the Arab loss was mitigated by the “Palestine” contradiction that then lay at the heart of Arab politics. “Palestine” was, and remains to some extent, a badge of shame, for it epitomizes the failure of the Arab states to achieve its goals. Yet it is only a badge; the persistence of the conflict, sharply inflected by the 1967 loss, has served as a raison d’être for most ruling Arab elites, their unflagging opposition to Israel as a symbol of legitimacy. In the parlous context of inter-Arab politics, too, the conflict has served as the only thing on which all the Arab regimes could symbolically unite. Non-democratic Arab elites have used the conflict both as a form of street control internally, and as a jousting lance in their relations with other Arab states.

Yet by far the most important consequence of the Arab defeat in 1967 was to free the Palestinian national movement from the clutches of the Arab states. The theory before June 1967 was that the Arab states would destroy Israel in a convulsive, epic war, and then hand Palestine over to the Palestinians. The hysteria that overtook the Arab street leading to war shows how widespread this theory was, and the war itself showed how hollow a promise it was. So the Palestinians took matters into their own hands for the first time, seizing control of the Palestine Liberation Organization from its Egyptian sponsors and reversing the theoretical dynamic of liberation: Palestinians would liberate Palestine, and that victory would supercharge and unify the Arabs to face the hydra-headed monster of Western imperialism. The key bookends of this transformation as it manifested itself in Arab politics writ large were the Rabat Arab Summit of 1974, which passed responsibility for “occupied Palestine” from Jordan to the PLO, and the 1988 decision by King Hussein to formally relinquish Jordan’s association with the West Bank, which it had annexed and ruled for 18 years after the 1949 Rhodes Armistice agreements.

But how would the Palestinians themselves, led by the new and authentic PLO, liberate Palestine? They had in mind a revolutionary people’s war, an insurrection focused on the territories Israel newly occupied. It took its inspiration from lukewarm Maoism and its example from the Vietcong. The attempted insurrection in the West Bank failed miserably and rapidly; terrorist attacks mounted from east of the Jordan and across the border with Egypt became the next tactical phase as Palestinian nationalism’s organizational expression fractured. In time Palestinian use of contiguous lands in Jordan and later in Lebanon to launch repeated terror attacks against Israeli civilians sparked civil wars in both countries. It did not bring about the “liberation” of even one square centimeter of “Palestine.”

Terrorism, however, did put the Palestinian issue “on the map” for much of the world, and now, fifty years later, Palestinians can have a state if their leaders really want one and are prepared to do what it takes to get it—the evidence so far suggesting that they don’t, and won’t. Nevertheless, looking back from fifty years’ hindsight, the Six Day War was about the best thing that could have happened for the Palestinians; that fact that they have not consolidated that windfall politically is their own doing, but everyone’s tragedy.

As to terrorism, it is true that the pusillanimous behavior of many governments in the 1970s, including some allied in NATO to the United States, helped the PLO shoot, bomb, and murder its way to political respectability. So one might venture that by helping to show that terrorism post-Six Day War can work at least to some extent, these governments bear some responsibility for the metathesis of nationalist, instrumentalist terrorism into the mass-murder apocalyptical kind we have witnessed more recently with al-Qaeda and ISIS. To me it’s another in a series of shiny arguments, more superficially attractive than fully persuasive. It is not entirely baseless, however.

But far more important than what the war did for the thinking of the Palestinians was what it did to the thinking of the Arab state leaders whose lands were now under Israeli occupation: Egypt, Jordan, and Syria. Before the war, Arab support for “Palestine” was highly theoretical, highly ineffectual, and in truth amounted merely to a symbolic football the Arab regimes used to compete with one another in the ethereal arena of pan-Arab fantasies. Now, suddenly, the core national interests of three Arab states—including the largest and most important one, Egypt—became directly and ineluctably entwined with the reality as opposed to the symbol of Israel.

The Egyptians, particularly after Nasser’s death brought Anwar es-Sadat to power, got downright pragmatic. Israel had something these three states wanted—chunks of their land. And the Egyptian and Jordanian leaderships, at least, knew that a price would have to be paid to redeem that pragmatism. Complications aplenty there were, as anyone who lived through the dozen years after the 1967 War knows well. Nevertheless, this critical divide among the Arabs—between state leaders who could afford to remain only symbolically engaged and those who could not—shaped inter-Arab politics then and still does to some degree today. First Egypt in March 1979 and then Jordan in October 1994 paid the price and made peace with Israel. It seemed like forever passed between June 1967 and March 1979, but it was less than a dozen years—quick by historical standards.

While Egypt recovered the entire Sinai through its peace arrangement with Israel, Jordan did not recover the West Bank. The war had shifted the political demography of the Hashemite Kingdom, sending more Palestinians to live among East Bankers—some now refugees twice over and some for the first time. The consequence was to intensify Jordan’s internalization of its problem with Palestinian nationalism: It had lost land but gained souls whose fealty to the monarchy was presumably weak. The benefit of peace to Jordan in 1984, and hence its main purpose from King Hussein’s point of view, was therefore not to regain territory but to strengthen the stake that both Israel and the United States had in Jordan’s stability in the face of future challenge from any quarter, internal and external alike.

Syria, do note, did not follow the Egyptian and Jordanian path to peace, and so the Golan Heights remain for all practical purposes part of Israel. The reasons have to do with the complex sectarian demography of the country, and specifically with the fact that since 1970 Syria has been ruled by a minoritarian sect in loose confederation with the country’s other non-Sunni minorities. The Alawi regime has needed the symbolic pan-Arab mantle of the Palestinian cause more than any other Arab state, particularly as one with a border with Israel. Regime leaders anyway did not consider the Golan to be their sectarian patrimony, but more important, peace and normalization seemed to the Syrian leadership more of a threat to its longevity (and to its ability to meddle in Lebanese affairs) than a benefit. Now that Syria as a territorial unit has dissolved in a brutal civil war, the legacy of 1967 has been rendered all but moot.

Does that mean that Egypt and Jordan essentially sold out the Palestinians, making a separate peace? Well, much political theater aside, yes. But they really had no choice, and not selling out the Palestinians would not have gained the Palestinians what they wanted anyway. That, in turn, left the Palestinians with little choice. Eventually, the PLO leadership also decided to “engage” Israel directly, but without giving up what it still called the “armed struggle.”

Its partial pragmatism, tactical in character, gained the PLO a partial advance for the Palestinians through the truncated Oslo process: a kind of government with a presence in Palestine; some “police” under arms; a transitional capital in Ramallah; wide international recognition; and more. Withal, the “territories” remain under Israeli security control, and the Palestinian economy (jobs, electricity grid, water, and more) remains essentially a hostage to Israel’s.

This has given rise to perhaps the most underappreciated irony in a conflict replete with them: First Israel internalized the Palestinian nationalist problem in June 1967 by occupying at length the West Bank and Gaza, and then the PLO internalized its Israel problem by drifting via Oslo into essential dependence on Israel for basic sustenance and even security support (against Hamas, for example). Note that it was hard for Israel to bomb PLO headquarters in Tunis in October 1985, but very easy to send a tank column into downtown Ramallah ten years later. It’s all so very odd, you may think, but there you have it.

The Bigger Picture

Now to the larger, international scene. What the Six Day War showed was that Soviet patronage of the Arabs and arms sales to them could deliver neither victory to the Arabs nor reflected advantage for the Soviet Union. This devalued the allure of Soviet regional overtures, reassured the Western-oriented Arab regimes, and hence played directly into the portfolio of U.S. and Western interests: keep the Soviets out, the oil flowing, and Israel in existence (the latter construed at the time as a moral-historical obligation, not a strategic desideratum).

The Johnson Administration figured the essence out, which is why in the aftermath of the war it did not do what the Eisenhower Administration did after the Suez War of 1956: pressure Israel to leave the territories it had conquered in return for promises that, in the event, turned out to be worthless. It rather brokered a new document—UNSCR 242—calling for withdrawal from territories (not “the” territories) in return for peace.

But it was not until the War of Attrition broke out in 1969 around and above the Suez Canal—a direct follow-on to the Six Day War—that the new Nixon Administration codified in policy this basic strategic understanding. To prevent and if possible roll back Soviet inroads in the Middle East, the U.S. government would guarantee continued Israeli military superiority—that was the start of the major U.S. military supply relationship to Israel that endures today (the younger set may not know it, but Israel won the Six Day War with a French-supplied air force). In short, nothing the Soviets could supply or do would help the Arabs regain their lands or make good their threats. The events of the Jordanian Civil War in September 1970, and the way Nixon Administration principles insisted on interpreting and speaking about that civil war, only deepened the conviction and the anchors of the policy.

On balance, the policy worked well, despite one painful interruption. By July 1972 President Sadat had sent a huge Soviet military mission packing out of Egypt, and was all but begging the United States to open a new relationship. Egypt had been by far the most critical of Soviet clients in the Middle East, and Sadat’s volte face represented a huge victory for U.S. diplomacy. Alas, neither the victory-besotted Israelis nor the increasingly distracted Americans paid Sadat the attention he craved—so he taunted the Soviets to give him just enough stuff to draw Jerusalem and Washington’s eyes his way: He started a war in October 1973. This also worked, leading as already noted to the March 1979 peace treaty—a geopolitical and psychological game-changer in the region and, ultimately, beyond.

For most practical purposes, Israel’s role as an effective proxy for U.S. power in the Middle East endured through the end of the Cold War, although its benefits paid out quietly, more often than not in what trouble it deterred as opposed to actively fought.6 And the Israeli-Egyptian relationship—imperfect as it may be—still endures as a guarantee that there can be no more Arab-Israeli conventional wars on the scale of 1967 or even 1973. These are both, at least partially, strategic achievements born of the conjoining of Israeli power and American diplomacy, and—it bears mentioning—these are achievements that were constructed and made to endure pretty much regardless of the state of play in Israel’s relations with the Palestinians.

Obviously, the end of the Cold War put paid to the structure of this regional American strategy, its logic dissipated through victory. In that sense, the larger global strategic impact of the Six Day War ended when the Berlin Wall fell. While Israel remains a strategic partner of the United States in the post-Cold War environment, largely through intelligence sharing and other activities, its value as strategic proxy diminished as the focus of U.S. concerns moved east, toward Iraq and the Gulf. In the 1991 Gulf War, for example, Israel through no fault of its own became a complication for American policy—a target set for Iraqi scuds—not an asset, such that the U.S. government pleaded with its Israel counterpart not to use its military power against a common foe.

Amid the sectarian and proxy wars of the present moment in the region, Israeli arms lack any point of political entré that can aid U.S. policy. Even when it comes to counterterrorism efforts, Israeli intelligence is indeed valuable but we will not see Israeli special forces attacking salafi terrorist organizations far from home. The last thing Israel needs is to persuade still more murderous enemies to gaze its way.

Only if the two parties come to focus on a common enemy—never the case during the Cold War, by the way, when for Israel the Arabs were the threat and for the United States the Soviets were the threat—could a truly robust U.S.-Israeli strategic partnership be born anew. And that common enemy, which could bring in also many Sunni Arab states and possibly Turkey as well, is of course Iran. But we are now very deep into the post-context of the Six Day War, more than six degrees of separation from any plausible causal skein leading back to June 1967.

A Smaller Picture

The war affected the political and social-psychological condition not only of state actors but of some others as well. As the Middle East crisis deepened in May 1967, I was a (nearly) 16-year old Jewish high school student in the Washington, DC area. Just like every American who was of age in November 1963 can remember where they were and what they were doing when they heard that President Kennedy had been assassinated, I suspect that just about every Jew of age anywhere in the world in May and June of 1967 can remember where they were and what they were doing when they heard that the war had started, and how they felt when it had ended.

We had been frightened, and afterwards we were relieved and even elated. It turned out that a lot of what we thought was true about the state of affairs at the time was incorrect. That was hardly a unique experience, but more important, over time the effects of the Six Day War on American Jewry and other Jewish communities outside Israel were dramatic—and the triangular relationship between Israel, American Jewry, and the United States has never since been the same.7

Figuring it all out has borne its own challenges, surprises, and disappointments. Those on all three sides who thought they knew what was going on—who was dependent on whom, who could count on whom, who had politically leverage over whom, and so on—learned better, often the hard way. But none of this has involved armies with modern weapons and high-level state diplomacies interacting; no, it is truly complicated and tends to generate narratives that are very, very shiny—so let’s just leave it at that.

Let us conclude by returning to where we began, using another’s much earlier conclusion as our prooftext. On Saturday, June 3, 1967, Israeli Prime Minister Levi Eshkol concluded a meeting of his inner cabinet with these words: “Nothing will be settled by a military victory. The Arabs will still be here.”

Eshkol (as well as the out-of-office but still prominent David Ben-Gurion) had counseled patience and restraint to Israel’s confident military leadership as the spring 1967 crisis grew, and only reluctantly came to the decision for war. Keenly sensing the ironies of history—Jewish history not least—he knew that the war would not be politically conclusive. He realized that whatever immediate threats needed to be extinguished, war would not deliver peace and security before, if ever, it delivered mixed and unanticipated consequences. He was right.

Not even the shrewdest statesmen are wise enough to foresee the consequences of a major war: When you pick up the gun, you roll the dice. That, I think, is no shiny lesson, but one more likely for the historically literate to recall the past’s many dull pains. May it help future leaders to control their own and others’ expectations if use force they must.

1I have written on the anniversary of the Six Day War before: See “Arab Loss Had Profound Effect on Politics in the Middle East,” Jewish Exponent, June 5, 1987; “1967: One War Won, a Few Others Started,” Newsday, April 30, 1998; and “Six Days, and Forty Years,” The American Spectator, June 5, 2007.

2Guy Laron, The Six-Day War: The Breaking of the Middle East (Yale University Press).

3See, for example, Isabella Ginor & Gideon Remez, Foxbats Over Dimona: The Soviets’ Nuclear Gamble in the Six-Day War (Yale University Press, 2007).

4On the former, note my “The Bullshistory of “Sykes-Picot”, The American Interest Online, May 16, 2016.

5For detail on what is meant by “pre-embedded” in “generically weak states,” see my “The Fall of Empires and the Formation of the Modern Middle East,” Orbis (Spring 2016).

6A point emphasized in Michael Mandelbaum, “1967’s Gift to America,” The American Interest Online, June 2, 2017.

7I have written of this triangular relationship elsewhere: “The Triangle Connecting the U.S., Israel and American Jewry May Be Coming Apart,” Tablet, November 5, 2013.

Macron Surging in Polls

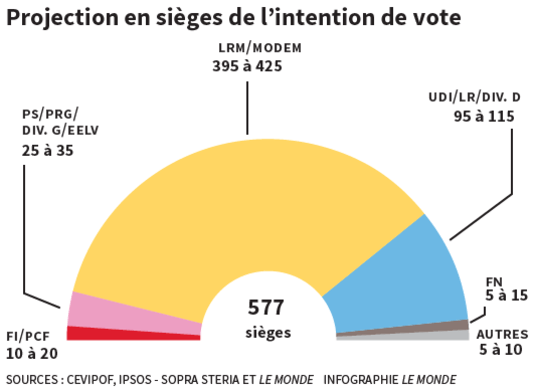

The latest polls show Emmanuel Macron’s new movement with a massive lead ahead of the upcoming parliamentary elections. Le Monde has the visualization:

According to Reuters, other surveys are only slightly less optimistic, showing 335 to 355 seats for La République En Marche. The center-right Les Républicains and the center-left Socialists have all but conceded the victory, and are now pleading with their discontented voters to keep the margins for Macron down.

“It’s all exploding. This was a solid fiefdom for us, but our huge pool of voters dried up after the presidential election,” Sebastien Vincini, a top Socialist official, said of his south-western Occitanie region, where Socialists held two thirds of the constituencies but expect to lose most of them.

FN chief Marine Le Pen topped the first round of the presidential election in April in Vincini’s Occitanie region, and Jean-Luc Melenchon’s far-left France Unbowed, which helped kill the Socialists’ chances in the presidentials, is getting stronger there.

But still for Vincini, “the biggest threat … comes from French voters’ desire to give Macron a majority”.

As we noted last week, Macron is likely to barge out of the gate with a series of labor market reforms. After all, he campaigned on just that, and given a mandate, will be sure to push his advantage as quickly as possible. But even still, it may not be smooth sailing. Labor unions will not take these reforms lying down, and given the fact that Macron’s coalition is by definition going to be broad, he may find friction even among his allies.

One thing is for sure, however: we are witness to an epochal realignment in French politics taking place. Though Macron has centrist inclinations, his party leans Left, and his rise has devastated the Socialists, perhaps permanently. There’s still fight in Les Républicains, however, who need to recalibrate their message in the wake of Marine Le Pen’s strong showing in the Presidential race in order to consolidate the Right.

Why Scholars and Policymakers Disagree

Academics are a conflicted lot, simultaneously cherishing and bemoaning their isolation from the world. Pursuing the life of the mind necessarily entails cultivating independence and even detachment from politics, the news cycle, and government policy. Yet detachment can easily become irrelevance, and in recent years, there has been a tidal wave of concern—from academics and non-academics alike—that international relations scholarship has become ever more remote from the affairs of state.

In a Washington Post op-ed written in 2009, Harvard scholar and former policymaker Joseph Nye warned of a “growing gap” between academics and government.1 A contemporaneous study concluded that “the walls surrounding the ivory tower have never seemed so high.”2 Robert Gallucci, then president of the MacArthur Foundation, lamented in 2014 that the academy was making only inadequate contributions to critical debates on global security and U.S. foreign policy.3 And in another stinging assessment issued that same year, New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof wrote that “some of the smartest thinkers on problems at home and around the world are university professors, but most of them just don’t matter in today’s great debates.”4

Such concerns are hardly new, of course; handwringing about academic irrelevance dates back decades. But there is nonetheless systematic evidence that the scholarship-policy gap is real and widening. A survey conducted in 2011 found that 85 percent of American international relations scholars felt that the academia-policy divide was as great or greater than it had been twenty to thirty years prior.5 The alienation appears to be mutual. Another recent survey, this time of policymakers, found that “what the academy is giving policymakers is not what they say they need from us.”6

The gap endures, moreover, despite myriad efforts to close it. The late, great international relations scholar Alexander George created his “Bridging the Gap” initiative to forge closer links between academia and government some fifty years ago. Secretary of Defense (and Georgetown University Ph.D.) Robert Gates created the Minerva Initiative in 2008 to encourage “eggheads” to do more research on critical national security issues.7 The list of such projects goes on, yet so does the gap. Why is this the case?

The explanations are diverse, and the reasons offered many. International relations scholars—particularly political scientists—increasingly emphasize abstruse methodologies and write in impenetrable prose. The professionalization of the disciplines has pushed scholars to focus on filling trivial lacunae in the literature rather than on addressing real-world problems. The tenure process punishes young scholars for “sucking up to power” and cultivating audiences beyond the academy. The long timelines of academic research and publishing make it difficult even for the most engaged scholars to offer prompt policy advice. Busy policymakers, for their part, simply lack time to engage academia as much as they might like.

Many of these factors are hard-wired into the academia-policy relationship, and many do indeed contribute to the gap. But there is also a more fundamental factor at work. On some of the most crucial issues of international security and American statecraft, the academic and policy communities have significantly—even dramatically—opposing views of what is at stake and what ought to be done. What we have here, then, is not a mere failure to communicate. It is a harder, yet more illuminating reality—that those who study international security and those who practice it see the same world through very different conceptual lenses.

Before we attempt a theory of the case, let us first illustrate the case. Consider, for instance, divergent policy and scholarly perspectives on nuclear proliferation.

For decades, there has been a bipartisan policy consensus that the spread of nuclear weapons represents a grave threat to American security, and that strong—even drastic—measures to impede proliferation are warranted. U.S. officials have long worried that aggressive rogue states would use nuclear weapons to blackmail America and its allies, and that the spread of the bomb would heighten the chances of nuclear terrorism, nuclear war, or other calamities. Accordingly, both Democratic and Republican administrations have used economic sanctions and coercive diplomacy to restrain potential proliferators. They have also seriously considered taking preventive military action against enemies pursuing nuclear weapons, from the Soviet Union and China during the Cold War to North Korea and Iran thereafter. In 2003, the United States even fought a counter-proliferation war to preventively disarm Saddam Hussein. For U.S. policymakers, it often seems, there is nothing more dangerous than a hostile state obtaining the bomb.

Scholars, however, are generally more sanguine. There are, certainly, diverse views within the academy on this matter. Yet most academics hold that the dangers of proliferation are overstated, the likelihood of nuclear terrorism or nuclear war is infinitesimal, and the costs of aggressive counter-proliferation policies dramatically outweigh the benefits. Dangerous adversaries such as the Soviet Union, Maoist China, and North Korea have gotten the bomb, after all, and we have lived to tell the tale. Leading academics even contend that nuclear proliferation can be stabilizing, because the iron logic of nuclear deterrence will foster peace between rivals. John Mearsheimer famously argued for a Ukrainian nuclear deterrent in the early 1990s, as U.S. officials were working feverishly to foreclose that very prospect.8 Kenneth Waltz, the dean of modern international relations theory, controversially argued that “more may be better,” and in 2012 he predicted—altogether contrary to established U.S. policy—that a nuclear Iran would exert a benign, stabilizing influence on the Middle East.9 When it comes to nuclear proliferation, the gap can be sizable indeed.

Or consider an even bigger question: what America’s grand strategy should be. Within the policy community, there has long been a virtually unassailable consensus that American engagement and activism are the pillars of a stable, prosperous, and democratic world. It follows that forward military deployments, alliance commitments, and the other aspects of a globe-straddling geopolitical posture are indispensable to global wellbeing and U.S. security. Call it “primacy,” “empire,” or “American leadership,” but this idea has been affirmed in every major U.S. strategy document reaching back decades, and it has been the single overarching theme of both Democratic and Republican foreign policy since World War II.10 This consensus has been challenged by the rise of Donald Trump, but the fact that so far his presidency has seen far more continuity than substantive change indicates that American globalism remains resilient.

Within the academy, however, a far dimmer view of that tradition prevails, and the dominant school of thought favors American retrenchment of a dramatic variety. “Offshore balancers” and advocates of “restraint” call for rolling back U.S. alliances and overseas force deployments, swearing off the significant use of force in all but the most exceptional circumstances, abandoning democracy-promotion and other “ideological” initiatives, and even encouraging selective nuclear proliferation to reduce America’s global burdens. These scholars argue that U.S. engagement is actually destabilizing and counterproductive—that it creates more enemies than it defeats, causes wars rather than prevents them, and weakens America rather than protects it. This view is no fringe position. It is supported by ivory-tower giants such as Mearsheimer, Barry Posen, and Stephen Walt. And, some prominent dissenters notwithstanding, it commands widespread adherence within the academy.

The gap is even wider when it comes to another critical issue: the concept of credibility. Since the early Cold War, U.S. policymakers have worried that if Washington fails to honor one commitment today, then adversaries and allies will doubt the sanctity of other commitments tomorrow. Such concerns have exerted a profound impact on U.S. policy; America fought major wars in Korea and Vietnam at least in part to avoid undermining the credibility of even more important guarantees in other parts of the globe. Conversely, most scholars argue credibility is a chimera; there is simply no observable connection between a country’s behavior in one crisis and what allies and adversaries expect it will do in the next. Policymakers insist that credibility is worth protecting; scholars reply that some of America’s costliest wars have been fought to sustain a tragic illusion.11

Nor are the disagreements between scholars and policymakers confined to abstract or theoretical issues. On some of the most significant and pitched foreign policy debates of the post-Cold War era, the battle lines have also been starkly drawn.

In the 1990s, for instance, the policy community coalesced—albeit after much internal debate—in support of expanding NATO to include former members of the Warsaw Pact. NATO enlargement would subsequently be carried out by Democratic and Republican administrations as the best way of ensuring U.S. influence, geopolitical stability, and democratic consolidation in Eastern Europe. International relations scholars, by contrast, overwhelmingly opposed NATO expansion on grounds that it was unnecessary and would deeply antagonize Russia. John Lewis Gaddis wrote that he could “recall no other moment when there was less support in our profession for a government policy”; similar views prevailed among Gaddis’s political science colleagues.12 The policymakers, in other words, concluded that NATO expansion was a strategic necessity; the scholars sided with George Kennan—the quintessential policymaker turned academic—in deeming it “a fateful error.”13

The clashes were even sharper over the decision to invade Iraq in 2003. That decision was, admittedly, contentious even within the policy world, but the Bush Administration—as well as most foreign policy elites, and significant bipartisan majorities in the Congress—ultimately resolved that war was the only way of disarming a dangerous and implacable adversary. That conclusion, however, was vociferously rejected by most international relations scholars, who argued that Saddam was not an imminent threat, that he could be contained and deterred at an acceptable price, and that war was likely to be very costly and unleash a flood of unwelcome consequences. Several dozen leading academics bought a full-page ad in the New York Times to make their case; hundreds of additional international relations scholars later signed a letter calling the invasion the “most misguided policy since Vietnam.”14