Peter L. Berger's Blog, page 185

May 30, 2017

If This Were a Republican Problem, You Couldn’t Keep the Press Away

The New York Post has an eyebrow-raising report on a scandal you probably haven’t heard about:

The criminal probe into a cadre of Capitol Hill techies who worked for dozens of Democratic lawmakers remains shrouded in mystery, months after their access to congressional IT systems was suspended.

It’s still not clear whether the investigation by the Capitol Police into the five staffers, who all have links to Pakistan, involves the theft of classified information.

The staffers are accused of stealing equipment and possible breaches of the House IT network, according to Politico, which first reported on the investigation in February.

If this was a scandal involving the Trump administration, the entire national media would be focused on it 24/7, with scoops and leaks gushing as hordes of top-drawer reporters chased a story that potentially connected government officials to major security breaches. But since the story involves Democrats, it’s apparently not that interesting to the mainstream press.

To be sure, there have been no charges and no convictions; it’s possible (as with the Trump-Russia scandal) that the wrongdoing may turn out to be relatively insignificant. But there’s enough black and oily smoke here that if this were a Republican problem, the MSM wouldn’t be able to get enough of it.

The Porcupine’s Dilemma

Facebook was making me feel depressed, so, in January 2015, I quit. I had been checking the site once a month to see what was going on with my perfectly average number of Friends. Of them, one regularly posted photos of the exquisite meals she prepared. Another uploaded photos of his smiling children in a pool somewhere. One shared links to articles about the lethargic U.S. Senate, along with aggravated commentary about America’s immanent decline. Another friend regularly posted photos of his black Labrador retriever, which had just died. And another posted news about her brother, who, after years battling mental illness, had also just died, at 42, of a heart attack. In high school, he was one of my best friends.

The overwhelming majority of Facebook’s content is comprised of a mélange of snippets like these, from the everyday lives of its 1.86 billion users, nearly half of them between the age of 18 and 35. Of the trillions of posts, here are seven, some from the aptly named Oversharers.com:

Home alone in the flat on Friday night, i didn’t realize it would be spend in my underpants watching Big Brother. A new low.

Love means rubbing Desitin on your husband’s ball rash.

I just burped loud enough that the dogs downstairs started barking.

I feel like I am the most blessed Mommy-to-be on the planet. . . . This was the most beautiful baby shower anyone could have asked for or dreamed of. Thank you to everyone that came out today. You made my day! I have the greatest friends/family anyone could ask for. A special thanks to my MIL, a true friend & second Mom!

Just had a patient’s pilar cyst explode over my shirt!

On this day 11 years ago I wore these shoes. Happy Anniversary, honey. You are a terrific husband, father, son, and artist. You inspire us.

Wondering if fajitas are really a good idea after having diarrhea all day.

Why do so many people post their most intimate moments, thoughts, and feelings for hundreds or thousands of vague acquaintances to see? And why do they so regularly read those of others? What is it about the #nofilter that has become so alluring and compelling? These are some of the most obvious questions of our times, and there’s been no small amount of ink spilled over them, both celebratory and sad.

Social critics worry that notions of intimacy, celebrity, and narcissism have become confused in American life. They argue that we expose our private selves online—sharing photos, videos, and thoughts with thousands of strangers—for a less than noble reason: We seek attention. Users who might otherwise feel invisible or undervalued in real life might achieve the kind of attention they need online. Self-revealing may also be an attempt to announce the private self in all its authenticity, a protest against the social norms of body weight, beauty, manliness, femininity, sexuality, gender identity, and so on. “What’s it worth to be yourself online?” asked the March 13, 2017 Time cover story about Snapchat, the disappearing-message system that allows you to share your real, unadorned self while donning zany digital puppy ears. For Snapchat, it’s apparently worth $24 billion in market capitalization.

But the longing to sing a song of self might just stem from the effects of modern consumer society, as critics such as Christopher Lasch and Daniel Bell feared. “Behind the chilianism of modern man is the megalomania of self-infinitization,” Bell wrote in 1976’s Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism. “Narcissism appears realistically to represent the best way of coping with the tensions and anxieties of modern life,” Lasch wrote, three years later.1 More recently, the New Yorker satirized the self-baring impulse in a fake letter to the magazine following the rejection of the author’s naked selfies: “What has our culture come to,” writes the huffy exhibitionist, “if bodies are considered…private, and not…the property of the global digital sphere?” Indeed the phenomenon of the selfie encapsulates the narcissistic reversal at the heart of this shift: mobile devices originally intended for communication with others—telephones—have become the primary instruments for broadcasting ourselves. A recent New York Times Customer Insight Group study reported that 68 percent of social media users “share to give people a better sense of who they are and what they care about”—a statistic evidencing that the verb “sharing” has somehow become reflexive.

Social scientists, too, have been fascinated by why people regularly share over social media, and they have come up with similar findings. A March 2017 study published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine concluded that people who spent the most time on social media, particularly Facebook, had twice the odds of having greater perceived social isolation.2 This is because Facebook is not just a platform to inform oneself about others’ lives but also to compare one’s life to those other lives—a use that can have unwanted consequences: “Young adults with high social media use seem to feel more socially isolated than their counterparts with low social media use,” the study reports, “[and] perceived social isolation (PSI) is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality.”

An earlier 2015 Computers and Human Behavior study found that “if Facebook is used to see how well an acquaintance is doing financially, or how happy an old friend is in a relationship—things that cause envy among users, use of the site can lead to feelings of depression.” The authors conducted a study of 736 college students and found that “regular” use of Facebook—checking the site multiple times a day—led to disproportionate levels of sadness brought on by status envy.3 But they also note, “by just blaming Facebook as a cause for depression, we miss a complex but important process that points to perceptions of subordination.” For many people, in fact, “Facebook is a gratifying experience that can even lessen depression.” (This is especially so if comparison with others has you coming out on top.)

That Facebook can alleviate troublesome feelings was also the result of a 2015 study by Jonah Berger and Eva Buechel of the University of Pennsylvania. In “Facebook Therapy: Why People Share Self-Relevant Content Online,” they found that sharing emotions and experiences via social media provides several immediate benefits, including boosting a sense of wellbeing through the perceived social support of Facebook “likes” or positive comments on one’s status update.4 The most frequent Facebook users were people who most required this kind of validation—people who “experience emotions more intensely and who have difficulty regulating their emotions on their own.” Their updates were motivated less by social comparison and more by the need to soothe negative feelings “by eliciting attention, affection, and social support.” Given these positive effects, online social networks may not be as detrimental to psychological wellness “as researchers and cultural critics fear.” Rather, sites such as Facebook offer easily accessible modes of self-therapy “for consumers to increase wellbeing.”

My own use of Facebook was motivated less by a therapeutic search for wellbeing or sympathetic community than by a sneaky, mean-spirited curiosity. Often I felt the presence of a very specific German noun when on the site: Fremdscham, the feeling of shame for someone else. But I also had a detached, haughty sense of being above the fray—of being outside of Facebook, there just to poke around. (I also suspected that I was not alone in this conceit.) I didn’t post anything except links to articles I either read or wrote, and, even then, only infrequently. I posted nothing private—no photos of family or friends, no personal feelings about anything or anyone. This made me feel as though I were separate from the dreary postings of food or children or dogs, and it also kept me safe from engaging with people I had long since forgotten. I derived my sense of Facebook satisfaction not from keeping tallies of likes or comments, but from not caring if I had them at all.

Eventually, however, I came to feel like a stranger in a strange land populated by adults who had all taken on, or never shed, the characteristics of teenagers. This explains my predominant feelings when on Facebook: arrogant, mean-spirited, and judgmental. Not exactly the personal traits one should want to nourish. But they make me wonder: Why would such reactions arise in the first place?

The Public-Private Overlap

For many of us, the onset of the social-media era and its accompanying illusions of intimacy might seem rather sudden. One day you’re using AOL to get on the internet via dial-up modem—static fuzz, static fuzz, ka-ping, ka-ping—and the next day there are photos of Kim Kardashian standing in a white bikini in her Los Angeles villa on your Instagram feed. The dislocation is jarring, but in hindsight it shouldn’t be: Where we are now as a culture obsessed with intimacy is where we have been traveling to for quite some time.

Just over forty years ago, the great American sociologist Richard Sennett traced the growth of what he termed an “ideology of intimacy” in Western life over the past two centuries. In The Fall of Public Man, published in February 1977, he described the decline of conventions that once regulated impersonal social interactions in public life, arguing that they had been on the wane since the middle of the 19th century. His book tracked the slow erasure of the boundary between public and private life in modern Western society, which, he argued, had left the contemporary world bereft of the benign norms of social interaction. Replacing the rituals that once mediated relations between strangers was a preference for “real” emotional exchange that discounted earlier social protocol, and vied for authenticity: “Today,” Sennett wrote, “manners and ritual interchanges with strangers are looked on as at best formal and dry, at worst as phony.”

This interpretation stemmed from the steady coalescing of spheres private and public, a division with a long tradition. Ancient Rome termed the division the res publica and res privatus, understood to be two sides of the same coin: There could be no true private self without a public one, and vice versa, and each sphere was satisfied by different things. The self in public was fulfilled by excellence, sociability, and achievement; the private self by intimacy, sincerity, and warmth. Adults could comfortably separate their public selves from private selves without feelings of guilt or inauthenticity. This intrapersonal division continued well into the 19th century, Sennett explains, evident in the social life of that century’s great Western cities—Paris and London, primarily. Public life consisted of behaviors associated with civility, cosmopolitanism, genteel deference, and sociable detachment. These sorts of behaviors kept the private self separate from its public role, and contrasted with what was intimate and natural—the private life of the family. Here, the softer, spiritual, intimate self was realized in the context of the home and the church.

It’s important to briefly recall that in the pre-Age of Reason, many Westerners conducted their most intimate and private relationship with God. Both close human relations and one’s own spiritual relationship to the divine required discipline, patience, hope, and cultivation to forge a meaningful relationship. Without a divine model, many believed, there was no model for human intimacy. Dialectically, the model of godly intimacy was also influenced by close human relations. In both, privacy and internal space were prerequisites.

This divine echo is evidenced in the etymology of the word “intimacy.” The Latin word intime appears multiple times in a pre-Reformation spiritual guidebook written between 1425 and 1427 by a German monk named Thomas á Kempis. His Imitation of Christ—the second-most translated book after the Bible, never once out of print, more than 6,000 editions—deploys the Latin word intime to describe the relationship one should have with Christ. The book’s first English translator, Thomas Whitford, in 1510, uses the words “closely” and “inward” for intime, already revealing the dual nature of what it is to be intimate. In Book 2, chapter 1, the Imitation reads, “Nec requiem aliquando habebis: nisi Christo intime fueris unitus.” Whitford’s translation: “Thou shalt never have rest unless thou art closely united to Christ within thee.” In Book 3, chapter 34, the declension intima: “O lux perpetua, cuncta creata transcendens lumina: fulgura coruscationem de sublimi penetrantem omnia cordis mei intima.” Whitford: “O everlasting Light! Far passing all things that are made, send down the beams of Thy lightings from above, and purify, glad, and clarify in me all the inward parts of my heart.” Something new in the notion of intimacy accompanied the beginning of the modern period, in the decades preceding the Reformation: Ideas of open and intimate relations between people and God were mirroring and affecting one another.

Spring forward to the 19th century, when problems in the private/public distinction began to emerge. Sennett argues that the main culprits were the engines of secularism and industrial capitalism driving the locomotive of modernity. Through case studies in social and political history, he examines how anxieties about authenticity, individualism, privacy, and intimacy eroded the well-established boundaries between public and private. One example is clothing: Once conceived of as a marker of one’s social status in an objective hierarchy or social class, clothing, now mass-produced and readily available, came to represent the subjective tastes of its wearer. Advertising emphasized the private self’s ability to improve one’s station though appearances; the public world, once ordered along the lines of commonly understood visual symbols, now looked fake and inauthentic—less real than the private world. The private self was thereby becoming discernible through its outward signs, and not always by choice: During the Victorian era, a palpable fear loomed that one might accidentally let signs slip—via language, a wrong glance, a mistaken gesture—that pointed to one’s “true” private nature or identity. The literature of the times is full of such plots and subplots.

Another example comes from politics: In the ancien regime (pre-Revolutionary France), it was widely understood that a political figure, when speaking in public or engaging with counterparts, was a kind of actor playing a public persona; he interacted with other stranger-actors regarding the concerns of public life. This changed when the cultural emphasis, owing much to Romanticism and the writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, shifted to individuals’ private lives and degraded the theatrical stage. A public official was no longer to be judged on how well he played a role or acted a part in public space; he was judged instead for congruence between his public image and his private self as to a guide to how much he meant what he said. Observers came look for signs of a “true” self to determine to what degree the political figure was in this sense authentic. Rather than take the public persona and its public actions as a common object to be ascertained, the public persona was now a mask to be scrutinized for alignment with the private self. This evaluative measure of politicians’ authenticity continues to this today.5

No surprise: traits like sincerity and authenticity were becoming important cultural values over the past century and a half; consequently, social rituals and playacting were steadily deemed insincere and inauthentic. This is because ritual does not express the self, but because it insists that the self submit to its contours. By the latter part of the 20th century, when Sennett was writing, strangers as social actors no longer had roles to play, no longer donned the masks that made robust public sphere engagement enjoyable. Instead, they were beginning to feel the need to display their private selves outwardly, to be who they were in private in public.

The result was what Sennett called a “tyranny of intimacy”—the burden of having to be oneself and close to others at all times. Detachment, meanwhile, had become taboo. “The reigning myth today,” he wrote, “is that all the evils of society can be understood as the evils of impersonality, alienation, and coldness. The sum of these is an ideology of intimacy.”

The Mediated Push for Pseudo-Intimacy

Before the arrival of the smartphone, Facebook, YouTube, Snapchat, Instagram, and Tumblr, modern culture—specifically in the realms of print, radio, and television media—began unsystematically encouraging the breakdown between the self and eager strangers. One need only look to magazines of the early 1920s such as True Story, which began openly dishing on adulterous affairs and the woes of a boring marriage. Print advertising had encroached so far into the intimate sphere by 1928 that the marketing pioneer Paul Nystrom deemed it “the necessary enemy of privacy.”

Then, by the early 1930s, radio had introduced the voices of American society into the private living rooms of millions of listeners; and soon the tabloids of the 1950s, like National Enquirer and Confidential, encouraged a push into the private lives of famous celebrities. The artistic counterculture of the late 1950s bespoke the ideology of intimacy by focusing intently on the importance of authenticity—seeking the reality of dark psychic forces underneath the curated self that lay behind the false masks of middle-class society. It was considered rebellious and avant-garde, indeed liberating, to get “beyond” politeness and civility and into others’ emotional nooks and psychic crannies, the location of the true self, behind the scrim of sociability. Given the conformist social mores of the 1940s and 1950s, this yearning is not difficult to understand.

The 1960s took to the charge en masse, of course, acting out against the bourgeois world of the postwar generation, insisting that drugs and spiritual awakening would vanquish society’s falseness so that authentic living and oneness with the universe could unfurl (this sentiment seems on the way back again, with the Brooklyn-San Fran love of the South American hallucinogen ayahuasca, and #vanlife). The therapeutic culture growing up in late-century urban America—caricatured by so many Woody Allen films—demanded the airing of weaknesses and secret desires, all in the hopes that they will be shared and, in turn, forge new and lasting emotional bonds with likeminded neurotics.

This psychotherapeutic urge parlayed into television guests sharing the details of their private lives in talk shows from the 1970s to the 1990s—from Phil Donahue and Oprah Winfrey to Ricki Lake and Dr. Phil. And then came reality television, which was built on the assumption, as MTV’s The Real World suggested, in 1992, that people wanted to “stop being polite and start getting real.” Enough with manners.

Survivor and Big Brother followed suit, as did subsequent shows on cable networks that forced strangers together for immediate rapport: Dating Naked featured two strangers stripping down for a first date; Married at First Sight legally bound them as soon as they met; Date My Mom let the kids decide. Over the past decade, the creation of televised conditions for immediate intimacy has expanded beyond niche entertainment and into a profitable and highly rated sector of the television market—something our reality-show President often reminds us of. As Jerry Springer told the Daily Beast in late 2016, “I’ve been tweeting all year that Hillary Clinton belongs in the White House and Donald Trump belongs on my show.” Insert rolled-eyes emoji.

At the crossroads of media and politics, the desire for a semblance of intimacy was famously found in Franklin Roosevelt’s 1933 Fireside Chats, which somberly entered Depression-era living rooms by addressing millions of Americans as “my friends.” Political operatives and consultants ever since have strategically pushed for making an impression of “emotional sincerity” as the most effective means of appealing to voters. “His eye contact is good with the panelists,” wrote 28-year-old media consultant Roger Ailes, in a memo about Richard Nixon’s TV performance, “but he should play a little more to the home audience via the head-on camera.” Ronald Reagan’s role as sincere President just trying to fix a broken Washington is well known to have mirrored Jimmy Stewart’s beloved Mr. Smith, and since the 1990s political candidates have gone a step further: seeking voter empathy by offering their own private struggles on the national public stage—Al Gore’s son’s near-death car accident, Hillary Clinton’s hard-driving father, John Edwards’ weepy apologies, Marco Rubio’s cigar-smoking Cuban grandfather, Michelle Obama and Anne Romney’s 2012 dueling convention speeches about how deeply they love their husbands. The result of an obsession with “authentic” political speech has also led to the popularity of such unscripted candidates as Rick Perry, Sarah Palin, and Donald Trump, who enjoy “tellin’ it like it is.” More important than misconstrued facts and figures and the ability to articulate coherent thoughts is how much speakers genuinely means what they say. Recall that in 2012 Perry, now Secretary of Energy, garnered praise for not remembering the basics of his own policy positions while on stage at a debate. That, his fans swooned, was a mark of a truly authentic candidate.

Politics and media are not alone. The cultural obsession with intimacy abounds in other cultural arenas, too. The popular web-short “First Kiss” features strangers making out; the photo book Touching Strangers snaps them awkwardly hugging. Companies like Allure Art and Love Is Art produce mail-order art kits for making “contemporary” works: paint-smeared couples roll atop a blank canvas while having sex. Since the early 1990s, artists have been making work so intimate that, as critic Jerry Saltz has written, you can eat it.6

Less messily, comedian Marc Maron’s wildly popular podcast WTF has become the go-to place for on-air revelation of deeply personal trauma, while nationwide “cuddle services” offer “trained professionals” who will canoodle with you for $80 an hour. In the world of publishing, the no-holds-barred confessional sees figures like Emily Gould and Lena Dunham trumpeting the virtues of the self-revealing tell-all, sometimes lightly disguised as fiction. Dunham’s latest project, Lenny, an email newsletter “where there’s no such thing as too much information,” fulfills its promise, with the first few issues describing a woman having her period at work and another receiving a vajacial—which sounds like what it is.

Given these myriad developments across the culture—and, to be clear, this is not to prudishly judge these new cultural artifacts, just to point them out—it’s difficult not to wonder why the collective yaw toward intimacy has gained so much force over the past decade, and why so many people are flocking to broadcast themselves online. We are simply digitally mirroring what has been happening in “analog” entertainment and politics for the past several decades. So, rather than being the perpetrators of some derelict new development, today’s youth are actually the inheritors of an ideology that has matured during their lifetimes but that stretches back at least a century.

The Ideology of Intimacy

Behind all the concrete cultural manifestations of the public-private breakdown lies an ideology, which functions dialectically by disciplining people to act according to a system, which in turn both validates the system’s norms and accordingly creates a set of expectations. Capitalism is an ideology. Egalitarianism is an ideology. Globalism is an ideology. Whatever it is that ISIS is preaching is at least in some ways an ideology when it’s not a theology. But what exactly is the ideology of intimacy? What kinds of beliefs are subsumed under its umbrella? What new norms and expectations has it been creating?

In brief, the ideology of intimacy promotes the idea that all social relationships are only real, authentic, and meaningful if they approach a person’s inner life and vulnerabilities. It encourages ever-increasing emotional closeness between individuals and groups. It treats the exchange of honest feelings as a moral good in itself, and it despises the pretense of social masks, professional roles, or ironic detachment.7 It decries interpersonal distance as fake or unnatural, aiming ultimately at what it valorizes as “the real,” which it takes to mean all things that are not artifice, adornment, detachment, or aloofness.

It abhors both shame and guilt because these feelings are believed to be imposed from the outside. This is not true, of course, or all guilt would be shame. But whereas guilt comes from your knowledge of your own wrongdoing, shame derives from an awareness of others’ judgment of your behavior. Tellingly, under the ideology of intimacy, inflected as it is with narcissistic tendencies, many people suffer intense feelings of shame but don’t often feel guilty, because they have little genuine concern for other people. Guilt requires an ability to intuit how someone else might feel. And so, in a culture obsessed with intimacy, “shaming” is instead understood to hinder a full expression of the self, blemishes and all, because it inserts doubt into the process of self-expression. Because the ideology of intimacy lionizes the experience of self-expression, it condemns all skeptics of full acceptance as oppressive.

It follows that the ideology of intimacy is decidedly anti-aristocratic and pro-bourgeois, for the former is historically coquettish and the latter is moralizing—the key to the bourgeoisie’s superiority complex since the mid-18th century.8 The ideology of intimacy, yoked to the development of modernity, thereby mutters a moral directive uttered like a mantra from the mouths of middlebrow culture for the past hundred years: It is good to feel close to people; social distance is bad and should be overcome. This mantra comes with a host of sub-mantras: The division between the public role and private self is artificial and should be erased. All privacy, secrecy, and dissimulation are bad. Boundaries that separate people from each other and, inwardly, from themselves must be eradicated. Transparency of motive at all times, for everyone. The ideology of intimacy is a core belief in both humanistic psychology and the American version of liberal democracy, and at its base are two ideas derived from Protestant Christianity: Everyone is equal before God, and what binds people of faith is not of this world—nations, power, secular laws—but rather something beyond it. The ideology of intimacy is most widespread in the United States.

Because of the ideology of intimacy, it is less conceivable now than perhaps ever before to insert a stopping point in a social interaction. It has produced an internal compulsion to share, whether we may like it or not. Less constrained by protocol or any set of shared norms to guide the rituals of social interaction, we are now less free to simply refuse further talking. “People have gotten really comfortable not only sharing more information,” says Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, “but more openly and with more people.” The expectation of privacy, he said in 2010, “is no longer a social norm.” And Evan Spiegel, the 27-year-old co-founder and CEO of Snapchat, said in a 2013 interview:

Now there’s no gap between offline and online. So we’re trying to create a place that is cognizant of that, where you can be in sweatpants, sitting eating cereal on a Friday night, and that’s O.K. It’s O.K. to be me even though I’m not on a fancy vacation and great-looking all the time.

In times of bad economic news and declining labor prospects for recent graduates, the subtitle of Christopher Lasch’s 1979 Culture of Narcissism returns with a vengeance: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations. Lasch is also premonitory here: “As social life becomes more warlike and barbaric, personal relations, which ostensibly provide relief from these conditions, take on the character of combat.”9

This shift toward a celebration of intimacy and the private self has clearly to do with the philosophy of egalitarianism, which aims to treat everyone alike despite their social standing or earned merit, but also with a modern therapeutic commandment that has gained so much currency over the past few decades that we no longer even see it, let alone question its worth: to be psychologically and emotionally healthy you must reveal increasing parts of yourself and express your honest feelings to others, regardless of how relevant, interesting, necessary, or appropriate; no matter what the relation of that person is to you. Philip Rieff, author of the groundbreaking The Triumph of the Therapeutic, in 1965, is no doubt weeping in his grave, his warnings rendered all for naught.

The therapeutic drill happens most readily by disclosing the most vulnerable parts of yourself and gently cajoling your interlocutor to do the same—or at least listen intently to you as you divulge yours. Let’s call it the narcissism of the give-and-take, masking as the generosity of “relating.” It is one of the most traded currencies we have—so, for example:

Marc Maron: When did your parents get divorced? How old were you?

Ethan Hawke: I was around three, so…

Marc Maron: So she was, what, 21, 22?

Ethan Hawke: Yeah, she was still in college. (…)

Marc Maron: Oh my God! It was just you and her?

Ethan Hawke: Yeah.

Marc Maron: So you were her buddy.

Ethan Hawke: Yeah, exactly.

Marc Maron: It’s weird those relationships—where you sorta, gotta stand in. You know what I mean? Cause, you know, yeah, my mom was 22 when she had me, and my dad was never around, so… So you get this weird extra emotional pressure, to deal with the mom, you know?

Ethan Hawke: You really do.10

Under the ideology of intimacy, subjective states are to be ferretted out; there is no warrant for hiding. We yearn for the parts of a person that are “underneath” the public and social parts; we long to make a emotional beeline to what is personal and inward, in the process denying a person his or her own mental space. In psychotherapeutic parlance, we’re seeking the id and what is hidden within it, intent upon unveiling the falseness of the constructed ego, intent on unearthing the inauthenticity of any given statement or position. We are deconstructing what used to be called a personality.

We distrust the ego because it is a curated presentation, because we are conscious of it being offered to us rather than our finding it. There is no doubt some truth in this notion of a curated presentation, as Erving Goffman made clear in The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (1956), Interaction Rituals (1967), and other books. But he never judged the phenomenon as an unmitigated evil. Now, a conversation that pivots away from the personal and toward things impersonal is assumed to be cold, deflecting, and unnatural, evidence of some kind of emotional stuntedness or hang-up. We characterize such behavior as passive “avoidance” rather than the actively strong decision of simply refusing. In all cases, wherever it appears, distance is to be overcome.

This cultural logic is also evident in sentiment about increased transparency in diplomatic communications. In 2010, WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange brought the logic of intimacy to a head with the assumption that everyone must say what they mean at all times: no hypocrisy, no deceit, no dissembling. “This document release reveals the contradictions between the U.S.’s public persona and what it says behind closed doors,” read WikiLeaks’ introduction to the diplomatic cables, “and shows that if citizens in a democracy want their governments to reflect their wishes, they should ask to see what’s going on behind the scenes.” The publication of 250,000 secret missives from Ambassadors and government representatives proved the mind-blowing fact that people in powerful positions don’t always say in public what they might say in private. Likewise Bradley, now Chelsea, Manning, the Army soldier who was charged with violating the Espionage Act, stealing government property, violating the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, and multiple counts of disobeying orders, insisted that her motivation was to provoke more sincerity in government—to make the United States say what it really means.

In both cases, there is disagreement with the state of affairs concerning the affairs of state that permits power to strategically dissociate what it says in public and what it says in private. As this naive neo-Rousseauan belief in the natural transparency of the pre-civilized noble savage becomes a new cultural norm, many elder statesmen are beginning to wonder if the new generation of diplomats will be prepared for the reliably dissembling antics of geopolitics. Under the ideology of intimacy, we have all become increasingly Maronesque or Assangesque, believing that closeness should be a moral goal for everyone.

The Porcupine’s Dilemma

The real world, alas, has never been so Edenic. For those of who relish having time alone or not sharing thoughts or feelings until we are ready (if ever), the spread of this ideology is troubling. Its pressure to abolish solitude and reservation seems to result from a devaluation of psychological sovereignty and intellectual freedom, or from the simple fear of being alone with one’s own mind.

More broadly, we might very easily wonder what the cultural stress upon intimacy says not just about us, but about the health and integrity of the public sphere of which we are a part. The German émigré philosopher Hannah Arendt worried about this in The Human Condition (1958), when she wrote, “The enlargement of the private sphere…does not constitute a public realm, but, on the contrary…means that the public realm has almost completely receded.” She published those ideas the same year color television joined millions of Americans in their living rooms, pushing the public world right through the television screen into the private sphere. Did the public world become bigger? Did the private world become smaller? Or did the public sphere simply overlap with privacy?

Theodor W. Adorno wondered about this overlap, too, and what the shifting relationship between the two said about the society in which it was happening. From his Los Angeles perch, he wrote in 1951 that, “estrangement shows itself precisely in the elimination of distance between people.” Like much of Adorno, this suggestion is puzzling, paradoxical, and profound. Untangled, it proffers the idea that the more that distance is eroded between people and the closer they seem to be, the more that objective social relations show their truly alienated state. In other words, what looks like closeness is actually an illusion of intimacy masking the reality of social alienation. Put even more baldly, alienated people seek intimacy on the cheap because they so yearn for the real thing and can’t find it.

The reasons for this social alienation may be many: Marx’s concern with the means of production, Simmel’s theory of money, Tönnies’ concern with the breakdown of primary relationships, C. Wright Mills’ suggestion that we have sold personality for capital, and various sociological ideas of powerlessness, normlessness, secularization, and atomization, along with the reality of living in a society such as that of the United States, with its relatively small social idea compared to that of societies built up from closer kindred relationships. Whichever sociological explanation you choose, the same Buddhist rationale applies: As with love and enlightenment, the more desperately we seek intimacy, the less likely we are to find it.

Fortunately, Adorno also illuminates the necessary condition for true intimacy, one in which we should take refuge in these illusorily intimate times: “Tenderness between people is nothing more than the awareness of the possibility of relations without purpose,” he wrote in Minima Moralia. This is both a hopeful and true statement, and it offers pause for reflection upon the problem of intimacy in our times: The more public our intimacy has become via social media and reality television, the more it conceals a commercial purpose. Consider Instagram posts of Kardashians, Heidi Klum, or Justin Bieber in their bedroom mirrors snapping selfies to attract new armies of adoring fans, or, more highbrow, the recent spate of failure memoirs and hard-luck confessionals: Benjamin Anastas’s Too Good to Be True, Sonia Sotomayor’s My Beloved World, Ben Lerner’s 10:04, and Karl Ove Knausgaard’s six-volume, Rousseauian autobiographical My Struggle. Consider, too, YouTube celebrities and other vlog diarists who generate millions of advertising dollars by tilling the rich soil of private experience for public consumption, negating the reality of intimacy by performing it publicly. And this is to say nothing of the avalanche of commercial publishing’s tawdry tales of personal or substance abuse, confessions of victimhood that also happen to sell a lot of books.

These trends, however seemingly banal, have given rise to the widespread belief that naked candor can do the work of talent, commitment to craft, and real creativity. They contribute to the creation of mass-illusions of intimacy where none exists. The production of instantaneous intimacy is of a kind with instant meals, instant fame, and instant spiritual awakening, in which quality is exchanged for speed. But everyone is not an artist, and radical self-exposure is not a replacement for the deeper effects of literature and art: the communion of psyches across time, the forging of sensibilities, the awakening of new ways of seeing and understanding the world—the awareness of the possibility of relations without purpose, commercial or otherwise.

Nevertheless, here we are: trying to find a spot that is not too close, but not too far, trying to recapture the value of detachment but still honoring the vitality and richness of private life. What’s the balance? How to reciprocate? How to not be a stick in the mud? We are right to want to be generous and empathetic, yes—but not too much to open ourselves to future attack or lose emotional leverage. What’s the ideal mix of distance and closeness? Finding this sweet spot is one of the most important interpersonal challenges, but it’s also something, despite its new intensity, the 19th-century German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer crystallized in a parable called “The Porcupines’ Dilemma,” described in Parerga und Paralipomena (1851):

On a cold winter’s day, a group of porcupines huddled together to stay warm and keep from freezing. But soon they felt one another’s quills and moved apart. When the need for warmth brought them closer together again, their quills again forced them apart. They were driven back and forth at the mercy of their discomforts until they found the distance from one another that provided both a maximum of warmth and a minimum of pain.

In human beings, the emptiness and monotony of the isolated self produces a need for society. This brings people together, but their many offensive qualities and intolerable faults drive them apart again. The optimum distance that they finally find that permits them to coexist is embodied in politeness and good manners. Because of this distance between us, we can only partially satisfy our need for warmth, but at the same time, we are spared the stab of one another’s quills.

We porcupines are faced with questions of degree and judgment—answers for which are not available through algorithms. Moral and ethical judgment, even amid the techno-utopianism of smart devices and wired homes, remains a humans-only feat. We should question the limits and effects of self-exposure. We should question our own behavior when we seek to ferret out the intimacy of strangers, and when others implore us to show our private selves at all times. We should consider these limits not because we pine for some Victorian or 1950s notion of propriety and uprightness, but because acts of discretion and the suppression of immediate thoughts and feelings are themselves morally expressive behaviors: They express the morality of shutting up. They express understanding, trust, and humility by listening and looking, by leaving room in our minds for other people, by being empathetic—by being, in an crucial way, more democratic, fallible, and self-possessed. These traits enact actual consideration of someone else’s situation. “It takes two years to learn how to speak,” Ernest Hemingway famously said, “and another sixty to learn to keep quiet.”

This kind of considerate distance is also known by a word that has fallen out of fashion, if not altogether out of common understanding: respect. Respect recognizes other people as free, autonomous beings capable of feeling, thinking, and making their own decisions. It grants others their full humanity. “Respect is a kind of ‘friendship’; without intimacy and without closeness,” Hannah Arendt wrote, nearly a decade before Aretha Franklin’s pop hit of that title. “It is regard for the person from the distance the space of the world puts between us.”

1Christopher Lasch, The Culture of Narcissism (Norton, 1979), p. 50.

2“Social Media Use and Perceived Social Isolation Among Young Adults in the U.S.” (accessed April 7, 2017).

3Margaret Duffy (Missouri University School of Journalism), Edson Tandoc (Nanyang Technological University, Singapore), and Patrick Ferrucci (Bradley University), “Facebook use, envy, and depression among college students: Is Facebook depressing?” Computers and Human Behavior; volume 43, February 2015, pp. 139-146.

4“Facebook Therapy: Why People Share Self-Relevant Content Online,” by Eva Buechel and Jonah Berger, Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania, p. 6.

5For the longer analysis, see “The Problem with Political Intimacy,” The American Interest (September-October 2015).

6A young German curator named Tanja Maka put up a show at Harvard University in the fall of 2001 that captured the art-spirit of the times: Eat Art: Joseph Beuys, Diether Roth, Sonja Alhaüser featured the work of three artists (the first two posthumously) and their uses of food as art. For Alhaüser, Maka writes, “Sculptures [are constructed of] edible materials—chocolate, gingerbread, caramel, and cake—that are intended to be consumed by the viewer.” At the end of the exhibit, all that remained of Alhaüser’s chocolate, popcorn, and marzipan vitrines and figurines were chunks of them strewn across on the gallery floor. Students and visitors to Harvard’s Busch-Reisinger Museum had eaten the rest. (Quoted from the exhibition catalogue for Eat Art: Joseph Beuys, Diether Roth, Sonja Alhaüser.)

7A recent flare-up in the irony debate (there have been plenty prior) was Princeton professor Christy Wampole’s 2012 New York Times op-ed “How to Live Without Irony,” in which she decried ironic posturing as politically destructive. She expressed the same sentiment again in late 2016, citing her initial article: “The Age of Irony ended abruptly on Nov. 9, 2016,” she writes, “when people in many of the irony-heavy communities I described—blue bubbles of educated, left-leaning, white middle-class people in cities, suburbia and college towns, of which I am a part—woke up to the sobering news of Donald J. Trump’s victory, and perhaps a new reason to ditch the culture of sarcasm and self-infantilization.” But irony’s death knell had already been rung on September 11, 2001, when Time’s Roger Rosenblatt identified the “End of the Age of Irony,” with its “oh-so-cool” ironists and their “vain stupidity.” Gerry Howard, the editorial director of Broadway Books wrote, “I think somebody should do a marker that says irony died on 9-11-01.” James Pinkerton of Newsday declared the death of irony and a victory for “sincerity, patriotism, and earnestness.” Most famously, Vanity Fair’s Graydon Carter wrote, “There’s going to be a seismic change. I think it’s the end of the age of irony.” In the following months, comedian and ironist Jon Stewart emerged as one of the country’s most trusted national figures on American political life. And following Trump’s election, Stephen Colbert rediscovered his mojo. For a fuller analysis of why we will always need irony, see my Chic Ironic Bitterness (University of Michigan Press, 2007), specifically chapter one, “Good Morning, America.”

8For more on this characterization, particularly of the hyper-moralizing German bourgeois ego, see Peter Sloterdijk, The Critique of Cynical Reason (University of Minnesota Press, 1983), especially the section “Critique of the Illusion of Privacy.”

9Lasch, p. 30.

10WTF with Marc Maron, Episode 693, with Ethan Hawke; airdate March 28, 2016.

What Happens on Campus Doesn’t Stay There

Campuses across the country kicked off “Sexual Assault Awareness Month” (SAAM) this April to the tune of several hundreds of thousands of dollars. Since 2001, every U.S. President has declared April to be SAAM, and President Trump has followed suit. Over the past decade in particular, an increasing number of Federal mandates encouraged colleges and universities to up the ante on such awareness programming, enforcing punitive measures should they fail to do so. This suggests an observation: Those who believe that an increased Federal role will solve campuses’ well-documented sexual woes might be suffering from something akin to April foolishness.

It’s not simply the bureaucratese-heavy emails that flood my inbox from consulting companies—designed with “best practices” in mind and in collusion with lawyerly types—that influence this observation. (Though it’s been several years since I worked as a student affairs professional, the industry likes to remind me of all the ways I, or my institution, should continue to fund their existence.) The headlines of the past few months alone are enough to give one pause about throwing more regulations, more lawyers, or more courts at campuses’ sex-related problems.

So does the lived experience of working in student affairs, at the nexus of competing student needs, parental demands, faculty expectations, legal obligations, and public opinion.

The situation on college campuses is well summed up by a recent flurry of articles and books. For a representative sample, take Stuart Taylor, Jr. and K.C. Johnson’s “The Campus Rape Frenzy: The Attack on Due Process at America’s Universities,” or Northwestern University Professor Laura Kipnis’s riveting Chronicle Review article, “Eyewitness to a Title IX Witch Trial,” an excerpt from her own recent book. The latter is not so much about Kipnis’s own surrealist encounter with Title IX enforcers as it is about her erstwhile Northwestern colleague Peter Ludlow, now effectively unemployable and living in Mexico. About American campuses, Kipnis observes, “Rampant accusation is the new norm.” About everything, she adds—but particularly about sex.

This commentary and the furious discussions it engenders feature the usual bêtes noires: Title IX, the Obama Administration’s “Dear Colleague” guidance letters, and campus administrative hearings. The consensus is that the Trump Administration ought to rescind the Obama-era directives, that Title IX ought to be re-tethered to its original purpose by Executive Order or Congress, and that colleges ought to be required by Federal mandate to hand over any sex-related incident to the criminal courts. Doing these things, so the reasoning goes, will restore proper due process and sanity to college campuses.

Doubtful.

For starters, Title IX is an ice cube beside the iceberg of campus-related regulations. Colleges are bound by numerous Federal laws even more aggressive, intrusive, and elastic than Title IX. These include the Jeanne Clery Disclosure of Campus Security Policy and Campus Crime Statistics Act, the 2015 Campus Sexual Violence Elimination Act (SaVE) amendment to the Clery Act, and the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), which has added its own conditions to the distribution of Federal student aid. The procedures, programming, and public reporting required by these laws is in addition to, and in frequent contention with, the separate legal requirements of such Federal regulations as the Family Education Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA) Privacy Rule, Title IX, Title VII, and Title IV.

SaVE, for example, requires colleges to report when any student on a public (non-university-owned) sidewalk experiences “emotional distress” directly or indirectly because of another student.1 In addition to requiring procedures and programming, these laws also restrict what university administrators can and cannot say about allegations of sexual violence—to whom (including off-campus police) they say it, about whom, and when.

Because these laws treat the alleged victim’s privacy as inviolable, the university is not allowed to identify, defend, or condemn him or her in any way, however much said victim or the accused broadcasts his or her side of the story. These laws do not mandate the same privacy protections for the accused. Because these laws empower the victim to choose the course(s) of redress, the university is not allowed to bring the case to outside police for investigation unless the victim has specifically requested it. And if the victim wants the university to drop whatever investigation or case it has against the accused, it is supposed to act accordingly—even if friends, parents, professors, or public opinion demand it do otherwise. Should the victim wish to involve the police, the academic institution still has to conduct its own separate investigation—just as any private business would conduct an internal review of an employee who allegedly violated its policies by committing a crime.

In sum, university officials are already following numerous Federal processes. So it’s well worth being skeptical of calls for the government to become even more involved in colleges’ internal processes. How much more entrenched in university life do we want it to be?

The situation on campuses isn’t only a product of Federal meddling, however; the colleges’ own policies and personnel more than contribute. University administrators are bound by the published “Code of Student Conduct” of their schools. Almost every student signs a form acknowledging that he or she has read the university’s code and will abide by it—a typical requirement for formal admittance to the university and class participation. Universities in turn are required to make public the “judicial processes” they will use in the event of a violation of the code (and every university must include sexual violence among the prohibited behaviors). Typically, this is laid out alongside the conduct code.

Academic institutions pay numerous lawyers and compliance officers, most of whom have been well steeped in “best practices” seminars, to design their specific judicial processes in consultation with faculty, staff, and student committees. This is all done to ensure that the institution has a judicial process that is fair to accused and accuser alike. However, these best practices are informed by a decades-long tradition of social justice advocacy premised on liberal or leftist assumptions about the nature of justice. Frequently, this tradition ascribes a person’s wrongdoing not to his or her own agency, but to any host of adverse circumstances, including ignorance. Thus, the “punishments” handed down by campus judicial processes, even for severe conduct violations, have frequently taken the form of “education sanctions” and community service.

Complicating matters is the fact that leveling fines or harsher sanctions is unpopular in student affairs circles, as it brings down the (frequently public) wrath of parents and any faculty advocates who hear only one side of the story. (FERPA seals the lips of the officials who know all of it.) If the matter draws wider negative publicity, the university’s president might be forced to step in. At this point, under pressure to show that the institution is “doing something,” the relevant officials often reverse course or overreact, applying or ignoring sections of the conduct code at will to save face within a social media-determined timeframe.

In addition, it’s not just the campus judicial process that’s influenced by left-leaning ideologies; student affairs professionals as a group are stridently progressive and unabashed about it. Just as certain judges and justices sometimes do, student affairs professionals may deliberately (though also sometimes lazily or ignorantly) violate their institutions’ published processes in the name of “justice,” because they do not think that these processes will produce the desired “message.” For example, if a straight female is sexually assaulted by her lesbian roommate at a typical American university, the victim stands a good chance of being instructed by a student affairs professional that she simply misunderstood the situation—and of receiving “educational sanctions” to rectify her own discriminatory, judgmental reaction.

This is not new to 2017, nor in itself a product of campus personnel scrambling to respond (however ham-fistedly) to Obama-era “Dear Colleague” letters. Such attitudes were shaping campuses with the implicit approval of cultural elites as well as attendees long before the Federal government involved itself in enforcing them.

While perhaps the universities were in the vanguard, the “sex problem” has since spread from the campus to the public sphere. We can speculate endlessly on the “why” of this. Perhaps one simple explanation lies in the fact that graduates who lived in such an atmosphere have now been members of the workforce and policymaking discussion for several years. But because it has spread, it’s unlikely to be solved anytime soon.

For example, nearly two decades ago, the listservs, discussion boards, and seminar sessions of the professional student affairs industry were filled with agonized handwringing about bathrooms. If an anatomical male was found in a restroom for anatomical females, could the former actually be found guilty of any wrongdoing if he said that he had decided that he identified as female for the day or afternoon or hour, no matter what he was actually doing in said female restroom? The strong consensus was that in such a case, the student affairs professional had no right to tell the anatomical male he hadn’t been a female for a random hour, and should drop any case against him.

This past month, the NCAA lifted its six-month ban on holding championship events in North Carolina after the state’s legislature and Governor repealed the “bathroom bill.” Said the N.C.A.A., frostily, about North Carolina: “[It has] minimally achieved a situation where we believe N.C.A.A. championships may be conducted in a nondiscriminatory environment.” What student affairs professionals haggled over on the internet more than a decade ago is now a polarizing issue in everything from legislative chambers to shopping malls to athletic courts.

Speaking of courts, consider a recent ruling by the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals. Judges Diane Woods and Richard Posner did some “judicial interpretive updating” (Posner’s words) in order to revise the 1964 Civil Rights Act ban on employment discrimination on the basis of “race, color, religion, sex, or national origin” to include sexual-orientation discrimination. The decision “updates” the meaning of “sex” from the definition Congress might have used in the not-so-distant past to what it needs to mean today, because “a broader understanding of the word ‘sex’ in Title VII than the original understanding is…required in order to be able to classify the discrimination of which (the plaintiff) complains as a form of sex discrimination.”

Of course, college administrators perform this same Kabuki dance about law and the meaning of words to arrive at the en vogue interpretation of sex. Sex is the casus belli in politics and culture; both the campus “courts” and the Federal courts are merely the beachheads.

For decades, we have blithely advocated the unrestricted right of personal autonomy, while also demanding that we not be held responsible for any ill effects. More than that, we want the law to facilitate our autonomy and smile on our choices. And humans invariably seek retribution, if not justice; we want victims to see their oppressors punished. Ironically, these demands require the interference of the authorities from which we proclaimed our freedom. The campus and the courtroom are much closer than they appear. And neither will restrain the other so long as the court of public opinion remains conflicted.

1To get a sense of the scope of these regulations, especially the Clery Act, see my article “Regulating Innocence on Campus: Title IX Is Not Even the Worst of It,” National Review, June 18, 2015.

Beijing Backs Switch from Coal to Natural Gas

China consumes about as much coal as every other country in the world combined, but its reliance on that heaviest polluting fossil fuel has peaked in recent years, and there’s evidence that natural gas—a baseload power alternative that produces roughly half as many greenhouse gases and far fewer local pollutants—is ready to do for China what it’s already done for the United States: knock Old King Coal off his throne. Bloomberg reports:

Though gas remains a small and expensive component in China’s fuel mix, demand is rising faster than expected for domestic and imported supplies. In April, consumption was 22 percent higher than the same month in 2016, and the total for the first four months of the year is up more than 12 percent, data from the National Development and Reform Commission show.

The results are encouraging analysts to upgrade their demand forecasts and may signal the government is on track to reach its goal of getting as much as 10 percent of its energy from gas by 2020. It’s also bolstering the outlook for hundreds of billions of dollars in possible investments by companies as far away as Russia, Australia and the U.S. to build gas pipelines and export infrastructure to feed the growing Chinese market.

Of course, China’s natural gas outlook isn’t anywhere near as rosy as America’s, as Beijing doesn’t have the benefit of a mature and booming shale industry. But China does have a great deal of natural gas trapped in shale—according to the Energy Information Administration, it has almost twice as much shale gas as the United States. However, a long list of reasons, from water scarcity to a lack of pipelines and roads to a general dearth of drilling expertise, have all conspired to stunt Beijing’s shale ambitions, and as a result the switch to natural gas is less about market economics in China, and more about government intervention.

And Beijing has a very good reason to intervene. Toxic smog from its many coal plants is choking the life out of the country’s many megacities, resulting in tremendous costs, both economic and social. Boosting natural gas production has become a major focus of China’s most recent five year plan. It won’t be a cheap switch, but the global LNG market is expanding as new suppliers around the world (from Australia to Qatar to the United States) are making the energy source more abundant than ever. As is the case with many other commodity markets, China will be counted upon to drive demand for LNG (and piped natural gas, as well) in the coming decades.

Gulf States in “Crisis” with Qatar

The normally taciturn politics of the Gulf Arab states have taken a bizarre turn this week after an apparent hack of Qatar News Agency (QNA) has thrown the region into a political crisis. As Bloomberg reports:

A United Arab Emirates minister said Gulf Arab monarchies are going through a “severe” crisis, an apparent reference to a spat between a Saudi-led alliance and Qatar over ties with Iran. […]

Tension has flared within the six-member bloc since state-run Qatar News Agency carried remarks criticizing efforts to isolate Iran after U.S. President Donald Trump and Saudi Arabia’s King Salman took turns to attack the Islamic Republic at an American-Muslim summit in Riyadh last week. Qatari officials said the statements, which have since been removed, were the work of hackers. The denial didn’t stop U.A.E. and Saudi media from accusing Qatar of breaking away from the GCC’s position against Iran.

The supposedly hacked statement from Emir Tamim was widely publicized in regional media before it was taken down. It was followed by an announcement on QNA’s twitter feed that Qatar was withdrawing its ambassadors from Saudi, Egypt, Kuwait, Bahrain and the UAE— likewise apparently faked and subsequently deleted.

The consequences, however, seem quite real. The Qatar-backed Al Jazeera network has now been blocked by Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Egypt, ever the opportunist when it comes to Gulf politics, blocked Al Jazeera while also using the incident as cover to crackdown on domestic media.

Meanwhile the war of words has only escalated. It’s an unwritten rule of the GCC that their media outlets, even the nominally independent ones, will refrain from criticism of member countries. Since the QNA hack, regional media have published a flurry of scathing articles directed at Qatar. In recent days the UAE-based Saudi-funded Al Arabiya, for example, has published as “analysis” articles with titles like “How Qatar and Iran’s hardliners are very much alike politically,” and “Hezbollah and Qatar – a story of forbidden love?” While English language reports have linked Qatar to Iran and terrorism, in Arabic the Saudi religious establishment have and for claiming a false descent from Wahhabism’s founder.

This is not quite the first time a serious rift has emerged between Qatar and the Saudi-led bloc. In 2014 Saudi, the UAE, and Bahrain withdrew their ambassadors over Qatar’s support for the Muslim Brotherhood following the 2013 military coup against the Brotherhood-led government in Egypt. While open criticism from the Gulf has been muted, Qatar has made a point of offering safe-haven to Islamist groups across the region including Hamas and the Taliban.

Even if these divisions are not new, they’re worth keeping track of, especially in light of Trump-backed anti-Iranian “Arab NATO” proposal at the recent summit in Riyadh.

May 29, 2017

Zbigniew Brzezinski’s Legacy

This weekend, our own Walter Russell Mead was interviewed by PBS about the legacy of Zbigniew Brzezinski. Watch the whole segment below:

Memorial Day

Today, on Memorial Day, beyond remembering those that have made the ultimate sacrifice for the United States—twenty-one in the past year in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan—it’s worth remembering that many thousands continue to put their lives on the line every single day all around this increasingly unstable world.

It’s also worth remembering the U.S. soldier killed by a white supremacist a week ago at the University of Maryland, as well as the veteran stabbed to death on an Oregon train for defending Muslims. Both of these stories are a reminder that under the strain of war and political polarization, the United States is slowly becoming an uglier and more dangerous place. On the Right and on the Left, there are too many people who think that the other side is actively evil, and we are seeing violence slowly leak into our politics.

It’s worth remembering that our problems aren’t really caused by our domestic political opponents. The shift from a mature industrial economy and the decline of the blue social model isn’t coming because bad people are doing bad things. Radical jihadis and terrorists stalking us from the shadows hate the American Left as much as they hate the American Right. And while we are divided—as a diverse and complicated society inevitably must be—on a whole range of social, economic and political issues, we have a long history of finding peaceful and creative compromise solutions to even the most difficult problems.

Memorial Day is not just a day to remember the sacrifices of those who have given their lives to defend us. It’s a time to honor their sacrifice by rededicating ourselves to the job of making this country worthy of these sacrifices—by cultivating the virtues of tolerance, engagement, respect and liberty that have made America great in the past—and will keep her great if we will honor and practice them now.

Trump’s Gifts to Merkel and Macron

Foreign policy is a funny thing: the results are often the opposite of what you want. Clearly President Trump went to the two European summits (the NATO summit in Brussels and the G-7 summit in Sicily) intending to deliver a tough message. But the net result of his intervention has been to reduce American influence in Europe and to give both Merkel and Macron some lovely political gifts.

Merkel has already taken her check to the bank; Trump’s negative messages, and the intense coverage of his undiplomatic language in the German press, allowed her to set her electoral house in order, undermine her Social Democratic challengers, and prepare the ground for some much needed policy changes once the German elections are over.

With the U.S. and Britain now “unreliable“, she said, Europe must now take more care of itself. This is a winning message in Germany. Unease about the United States is always a factor in German politics, and Trump makes George W. Bush and Ronald Reagan look popular in Germany. His unilateralism, his anti-German rhetoric, his open skepticism about climate change all grate on German sensibilities; from the far-Left to the far-Right, there is hardly a person in Germany who hasn’t been both offended and annoyed by Trump. If Trump had behaved more diplomatically in Brussels and Sicily, spouting bland platitudes about cooperation, hailing the depth of U.S.-German friendship and praising Angela Merkel for her leadership, she would now be trying to figure out how to distance herself from an unwelcome and politically damaging embrace. But as it is, she can criticize Trump, distance her Administration and her party from an unpopular U.S. president, and do it all while professing undying loyalty to the highest values of the western alliance.

This is a wonderful break for her. Traditionally in German politics, the center-Right coalition has stood for closer cooperation with the United States; back in the 1950s that worked fairly well, as enough Germans were worried by the Soviet threat to prefer a close relationship with the U.S. At times since then—during the Vietnam War, for example, and again during the Iraq War, the German Left has been able to play the U.S. card against the Right.

Not this time; Merkel has seized the high anti-Trump ground; the Social Democrats will be reduced to squeaking “Us, too!”

Meanwhile, the sense of unease that many Germans will feel as unpredictable changes rock the geopolitical landscape also redounds to Merkel’s advantage. She is the reassuring presence Germans have come to trust; many voters will think this is a bad time to risk disruptive changes in the German government.

Finally, the excitement over the friction with Trump helps bury any lingering bitterness on the German Right about the ill-judged migration initiative that put the first serious dent in Merkel’s public standing since she took office back in 2005. The Right will be united, the Left has lost its best cards, and the voters will be looking for stability rather than change.

For all this Angela Merkel owes Donald Trump a hearty thanks, though we doubt that she will send him a thank you note—or that he would be pleased by it if she did.

But helpful as Trump’s visit was to the German conservative, he may have done a bigger favor for the upstart Frenchman currently in the Elysée. Emmanuel Macron’s hand has been strengthened heading into what could be the most important round of talks between France and Germany in half a century.

The reason: an insecure and worried Germany will now need a strong partnership with France more than ever. Merkel can’t afford to see the EU rupture over Franco-German differences and can now use the parlous state of the international system to make a strong case to German public opinion for concessions to France (and other soft-money countries in Europe) that would be impossible under other circumstances.

Germany right now has bad relations with Russia, trouble with the United States, is losing Britain as a partner in the EU, and simply cannot afford to see the EU weaken. There is only one way to protect the EU and stabilize Germany’s neighborhood, and that is to re-invigorate the Franco-German partnership. This cannot be done without more concessions on eurozone governance than Germany has been willing to make in the past.

Macron and his team now have a unique opportunity to draw up a blueprint for eurozone reform that the Germans might actually accept. This is something that no French President has had for 20 years; it represents a historic opportunity for the new team.

The revival of French influence in the EU won’t be good news for Britain; it’s unfortunately likely that part of the French price will be a somewhat more protectionist tone in the Brexit negotiations. But overall, the slow withering away of the vitality of the eurozone and the sapping of the strength of the EU in the last ten years has been a disaster for the West, and for world order. A rebalancing EU may be less open and less Atlanticist than most American foreign policy experts might prefer, but the development of a united Europe has been a core American interest since the 1940s and remains one today.

Trump did not go to Europe planning to punish Britain, reward Germany and promote France, nor did he intend to revitalize the European project. But that may be exactly what he ended up doing. Interesting times ahead.

May 28, 2017

Assessing the Brussels Wreckage

So, what do they say now in order to qualify his every pronouncement? After Donald Trump’s epic dress-down of the leaders of the democratic world, we see legions of self-avowed pragmatists coming forth to right-phrase the U.S. President. They say that he did not mean what he said, or failed to say—on NATO, on trade, on migration, on Europe, and on Germany. They maintain that haranguing allies over their defense spending is just a negotiating tactic of a successful businessman. They claim that his advisers, anyway, said all the right things—even if the President himself fell silent when it mattered most. They say Donald Trump is learning, like every new U.S. President. And they argue that Europeans should look at what he does, not listen to what he says.

Yes, they allege all of these things. But their words sound increasingly hollow. We should identify them for what they are: the narrative of the party of wishful thinking. All these analysts, former officials, and think tankers—with the weight of their titles and the years of their experience—would simply whitewash the muddy stream of consciousness that this U.S. President calls policy.

The reality is that words matter in international relations, as they do most everywhere else. The credibility of alliances is not solely based on treaties and military hardware, but on trust and the belief of others that an alliance will actually do what it has set out and is sworn to do. We should picture Vladimir Putin doing cartwheels in the Kremlin upon hearing that the U.S. President is now actively avoiding recommitting to NATO’s common defense clause.

It is painful to watch this spectacle, and even more painful to watch it from Germany. This is not simply because of the manifest anti-Germanism that this American leader displays. (All these bad, bad Germans doing harm to poor America!) It is painful to watch Donald Trump shoving aside the leaders of allied nations and, in the process, shoving aside the world order our forbears built. The glib callousness with which he does it is nothing less than frightening.

My country has benefited greatly from the system of cooperation among democratic nations that over the past nearly seventy years we have gotten used to calling the liberal international order. Becoming part of that postwar order has been crucial to Germany’s rehabilitation and reintegration effort. The Europe that had suffered greatly from German hubris was now transformed into a ring of friends organized around first NATO and then the European Union. This constituted a kind of soft shield, part armor and part nest, that enabled Germans to revive their country as an economic power, but, much more than that, to look at each other after the catastrophe of war in order to face and overcome the fears within without having to simultaneously face other fears from without. In terms of wealth creation and economic stability, security and protection of individual rights, no other international system in history has come close to delivering as many goods to Germans as the current liberal international order.

Because this system has been both good to us and good for us, Germany in the post-Cold War period has begun to take on the responsibility of becoming a regional guarantor of this order rather than just being a beneficiary of it. But Germany cannot do this alone. Without the United States as a full partner, the weight of political leadership may become too much for it to bear and it will certainly be perceived to be overbearing by other European countries.

And now along comes Donald Trump. He sees the period of America’s unrivaled power, wealth, and influence as a road leading to national loss and decline. When he travels his country he sees “American carnage.” And when he looks at its foreign relations, he sees allies and partners taking advantage of American goodness and American generosity. In his narrative, America is getting a raw deal, whether on trade or on alliance defense. Trade is not a tide that lifts all boats, but a zero-sum game. NATO is not a system of collective defense that protects the United States and its interests, but rather a murky agreement that allows Europeans to buy protection from the United States. In this thinking, the U.S. military is something akin to a foreign legion for which Europeans don’t pay the bills.

For his followers, President Trump’s Brussels tirade was his finest nationalist hour. In Germany, it is seen as yet more evidence that Trump wants to unmoor a system that Germany wants to preserve. The America that this President envisions is a revisionist power; Germany is fundamentally a status quo power.

To Germans, this is a problem from hell, a seemingly insoluble conundrum. All of Germany’s major political parties—and the vast majority of Germans with them—want to uphold the order that the West built. But to do so requires American leadership, not just in arms, but in all the ways that matter: in foresight, moral clarity, and good judgment.

The only chance to best this problem from hell might be to protect transatlantic relations from Donald Trump as best we can. To do that, Germany suddenly needs what it did not need for decades: a strategy for dealing with the United States. In recent years, American-German relations were no longer about these two countries, but about what they did together in the world. It was a relationship of kinship that, in the end, was about policy coordination. Now, it is again about basics. German leaders now need to figure out how to mix accommodation, confrontation, and tactical stalling in their dealings with the new Administration.

It did not have to be this way. In the words of U.S. President Donald Trump: It’s sad, very sad.

The American Retirement System Is in Trouble

America’s beleaguered retirement system is a three-legged stool, comprised of employer plans, private savings, and entitlement programs. The major development of the last two generations has been the evaporation of reliable employer plans: Outside of the public sector, few employers offer defined-benefit pensions. 401(k) plans have not made up the difference, and most Americans are not putting aside enough in individual accounts to retire with dignity.

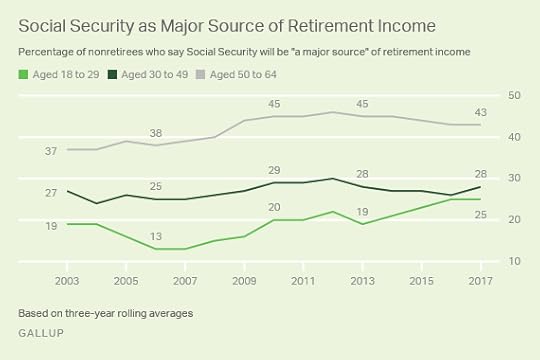

Partly as a result, a growing share of Americans say they will be leaning more heavily on the third leg of the stool: the Social Security system. A new Gallup poll shows that both Millennials and Baby Boomers are increasingly likely to envision a retirement where they are dependent on payments from Uncle Sam (Gen Xers haven’t shown as much of a shift).

The median Social Security payment is about $16,000 per year for an individual—not enough for a decent retirement. Moreover, the Social Security system is not adequately funded for the long-term; Millennials today will not have access to a robust program when they reach retirement age unless taxes are increased or benefits are reduced in the interim.