Peter L. Berger's Blog, page 188

May 24, 2017

Moody’s Cuts China Down To Size

Moody’s has downgraded China’s sovereign debt rating for the first time since 1989, as the Long March toward a Chinese meltdown continues. The Wall Street Journal has more:

In a Wednesday statement, Moody’s said it downgraded China’s rating to A1 from Aa3, while changing its outlook to stable from negative. In March of last year, it cut China’s outlook to negative from stable. […]

The news triggered an early selloff in Chinese stocks, with shares in Shanghai falling more than 1% before recovering, in addition to modest losses for the Chinese currency in the freely traded offshore market. […]

“The downgrade reflects Moody’s expectation that China’s financial strength will erode somewhat over the coming years, with economy-wide debt continuing to rise as potential growth slows,” Moody’s said in the statement.

“While ongoing progress on reforms is likely to transform the economy and financial system over time, it is not likely to prevent a further material rise in economy-wide debt, and the consequent increase in contingent liabilities for the government,” it added.

The Chinese Finance Ministry, sure enough, is disputing the Moody’s verdict, and China’s tightly insulated domestic markets have shrugged off the demotion. But the rating is just another confirmation of what foreign investors have slowly been realizing: China’s debt-fueled growth model is unsustainable in the long run, and Beijing is seeing diminishing returns from its credit binge.

The WSJ analysis picks up on all the usual signs of stress: not just China’s rapidly rising debt load and expanding asset bubbles, but the increasingly heavy-handed measures that Beijing has been taking to crack down on systemic risk in the economy. From sudden interest rate hikes to heightened regulatory scrutiny over shadow banking, the central bank has been leading an aggressive campaign of fiscal tightening in recent months. But none of these short-term measures have altered analysts’ expectations that serious economic reform has stalled, and that all of China’s underlying problems—from the excess capacity in its industrial sector to its current bout of capital flight—are here to stay.

As always, it is a fool’s errand to predict an imminent collapse of the Chinese economy; Beijing’s economic engineers have repeatedly managed to stave off catastrophe in the past. But it looks increasingly likely that China could repeat the Japanese scenario, with excess debt leading to a “Lost Decade” of sluggish stagnation—and foreign investors are pricing in the risk accordingly.

Pew: NATO Approval on the Rise

President Trump is heading to a NATO summit in Brussels this week, looking to patch things up with an alliance he once infamously denounced as “obsolete.” According to a new Pew Research Center survey, growing majorities on both sides of the Atlantic beg to differ with that assessment:

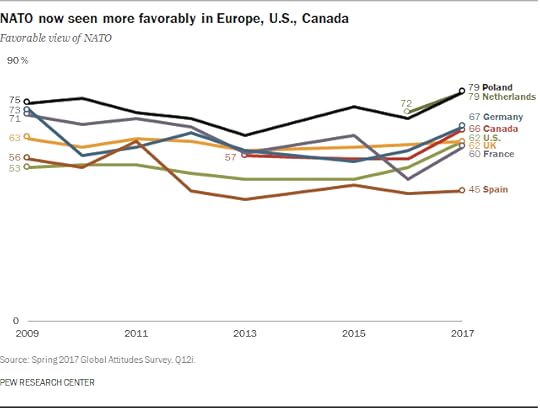

In both North America and Europe, views of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) have generally improved over the past year. Today, roughly six-in-ten Americans hold a favorable opinion of the security alliance, up from just over half in 2016, according to a new Pew Research Center survey. Majority support for NATO has also strengthened in Canada, Germany, the Netherlands and Poland. And after a steep decline a year ago, most French again express a favorable view of the security alliance.

Sometimes, the simplest explanation is the most compelling: the uptick in NATO support correlates with Trump being elected. Intentionally or otherwise, Trump’s doubts about an alliance that had previously been taken for granted seems to have put the fear of God into our ill-armed European allies—especially those most in danger from a resurgent Russia.

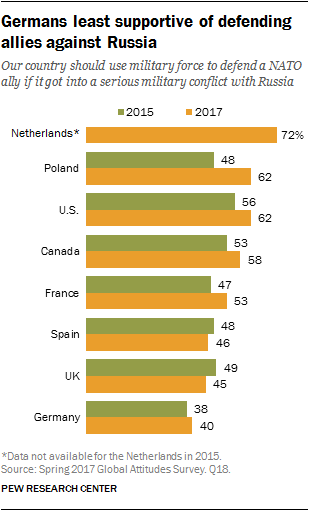

Indeed, the Pew data suggests that countries whose publics perceived Russia as a serious threat were also more willing to come to other NATO allies’ defense. That helps explain why Poland is near the top of the pack, while more distant countries like Spain and the UK, which feel less threatened by Moscow, lagged behind. Germany, meanwhile, presents a unique case. While 67% of Germans now look favorably on NATO, only 40% support defending allies against a Russian attack—a paradox likely explained both by pro-Russia sentiment among the German people and Berlin’s well-established aversion to defense commitments.

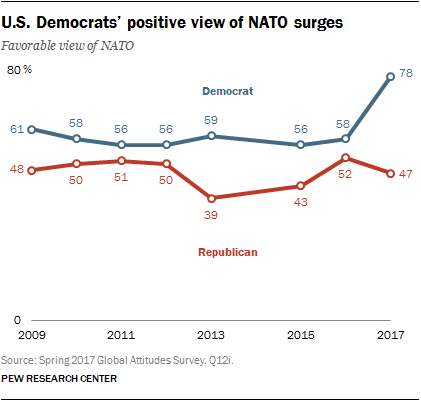

The Pew data also shows how Trump has shaped domestic views on NATO. Democrats registered a 20-point swing in favor of NATO, in a clear partisan reaction against Trump’s campaign trail positions. The effect on Republicans was smaller but still notable, with a 5% decrease in GOP support for NATO. It is telling, however, that Republicans have had more dubious views of the alliance for some time now—a sign that Trump’s skepticism about NATO had more buy-in from the Republican base than other polling has suggested.

Overall, 66% of Europeans surveyed still trust the U.S. to come to their defense in the event of a Russian attack, and 62% of Americans believe the U.S. should do so. President Trump is expected to explicitly endorse NATO’s Article 5 in Brussels tomorrow, putting an end to lingering anxiety about his commitment to the alliance. That’s all to the good—an alliance needs to be credible in order to be useful as a deterrent against revisionist powers.

Still, one has to wonder: will allies have been rattled enough to follow through on their commitments to spending 2 percent of GDP on defense even after President Trump has stopped playing bad cop?

No More Shenanigans

For four decades now, progressive and conservative policymakers have offered up different reform plans for health care. All have failed in some way, to the degree that each has played a role in perpetuating a system dogged by constant crisis, resulting in the awful state of affairs in which we find ourselves today. With the recent collapse of one Republican plan, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) remains in place—a ticking time bomb that both political parties know will eventually explode.

I am a physician, which may be useful here, because doctors are skeptics by nature and distrustful of ideologies. When it comes to working with one person or a system composed of people, whether it is a small system like the doctor-patient relationship or a large system like health care, a doctor knows that theories must give way to practicalities, an acceptance of imperfections and impurities, and the natural give-and-take between people. Today, serious health care reform demands this sensible outlook as much as the doctor-patient relationship does. It demands skepticism, not ideology.

“Something needs to be done about health care,” people cried in 2010, when the ACA was passed. And, in truth, something did need to be done. Progressives argued then and still that the ACA was the right solution. Facts suggest otherwise.

The most relevant facts preceding the passage of the ACA involved rising health care costs and the number of uninsured. In 2009, health care costs continued to rise much faster than the rate of inflation. Insurance premiums reflected that rise. From 2006 to 2009, the cost of the average family health insurance plan rose 31 percent. From 2001 to 2006, it rose 63 percent.1

In 2009, 45 million Americans were uninsured. Progressives cried “poverty,” yet upon closer examination, many people were uninsured for reasons other than a lack of money.2 In fact, the poor then (as now) had Medicaid, while the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), passed in 1997, insured poor families with children just above the Medicaid eligibility level. Instead, many young working people made a calculated decision not to buy insurance because they thought it not worth their while. Several million uninsured were eligible for Medicaid or CHIP, but for some reason refused to sign up. Ten million uninsured were non-citizens, which constituted more of a sociological problem than an insurance problem. Curiously, another ten million uninsured lived in households with annual incomes greater than $75,000 and thus were able to buy insurance but for some reason did not.

The real number of chronically uninsured was therefore closer to 12 million, not 45 million. Many of these 12 million people worked in small businesses. At the time, the small group insurance market was very unstable, with exploding premiums, in part because small businesses lacked sufficient numbers of employees to pool risk. Other uninsured people had preexisting diseases and could not get insurance. In retrospect, one wonders why the Federal government just didn’t buy these 12 million people private insurance plans. Given the average cost of insurance in 2008, the price would have been about $72 billion, or $720 billion over ten years. When President Obama signed the ACA, he predicted it would cost $940 billion over ten years.3 Just giving the uninsured private insurance plans might have saved a lot of money and headache. Indeed, in 2016, the Department of Health and Human Services announced that 20 million people had gained insurance under the ACA. But that left 25 million of the original 45 million still uninsured. Too little was gained for too high a price.

But that was then, and we live in the here and now. So the question we must ask is: Where do we go next in health care? The answer begins with admitting how little has changed not just in the past seven years, but in the past forty. True, some problems have been ameliorated by the ACA—for example, the number of uninsured has decreased, people can no longer be turned down for health insurance because of preexisting conditions, and young people can remain on their parents’ insurance plans until age 26. All that is to the good. But what hasn’t changed is at least equally significant.

When examining the standard pie graph of U.S. health care spending, one notices that the pie slices have hardly changed since the 1980s.4 In 2015, physician and clinical services comprised 20 percent of the pie; in 1990, they were 19 percent. In 2015, hospital costs were 32 percent of the pie; in 1990, they were 38 percent. In 2015, prescription drugs counted for 10 percent of the pie; in 1990, they were lumped in with dental costs and home health costs, for a total of 23 percent—yet if one assumes that little change in dental costs (4 percent) and home health costs (8 percent) since 1990, prescription drugs accounted for roughly 11 percent of the pie in 1990, roughly the same as today. Even out-of-pocket costs, the nemesis of so many low- and middle-income Americans, have barely changed. In 2015, they comprised 11 percent of the health-spending pie; in 1990, they comprised 20 percent of the pie (even more than today), although the pie then failed to include such categories as “investment,” “public health activities,” and “other programs” as part of total health spending. Upon injecting those programs into the 1990s pie, the 20 percent figure would likely drift down toward today’s number.

So much time and energy spent on new theories of health care delivery, so many papers published on the vital role of quality indicators and preventive medicine, so many conferences held on accountable care organizations, the Cleveland Clinic model, health savings accounts, and other delivery methods, and yet the borders within the pie have barely moved! Both progressive and conservative theories designed to revolutionize health care have proved ineffectual. All that has happened over the past four decades is that the pie itself has steadily grown bigger, in part from population growth, but also from the introduction of more services, drugs, and technologies, and the increase in prices—the same old story.

The most relevant change introduced by the ACA, at least for the average person, lies below the level of ideology: The ACA simply shifted the financial burden of health care from one group of working people to another. People who suffered in the past—for example, those with incomes just above the old Medicaid eligibility level—can now go on Medicaid. Some people working in small businesses are now eligible for government subsidies. Yet other working people have actually been hurt by the ACA. Young low-income families who in the past refused health insurance must now buy it, even though it comes with a $6,000 deductible, making it useless for most such people. But it’s either that or pay a fine.

Moreover, people with slightly above-average incomes in the individual insurance market must now pay more to subsidize the more favorable position of those just below them. Many working people saw their hours cut, or their labor outsourced to contractors, so that employers would not have to pay for their health care. Some low-income working families became eligible for enormous subsidies on the ACA exchanges while similarly positioned families working in a different environment (for example, in fast food restaurants) were eligible for much smaller subsidies that were manifestly insufficient to cover their insurance costs. So it’s no wonder that people in this category positively hate the ACA.

Curiously (or not), the people who did well under the ACA are the people who always do well. These include the rich, because the rich can take any hit. The one hit the rich took, a new tax on dividends, hardly elicited a yawn from them. People working full-time for large businesses also continue to do well. Their Cadillac plans remain tax-deductible, with the implementation of a tax on part of their premiums continually postponed. In addition, large businesses retain their advantage in pooling risk. And the very poor continue to do well—they have Medicaid. The overall state of affairs today is thus not appreciably different from the 1980s or 1990s.

All that said, there is a change in the health care data that suggests a new direction for reform. In 1990, the private sector was responsible for 58 percent of health care expenditures; public budgets accounted for 42 percent. Today, private health insurance and out of pocket expenses are responsible for 44 percent of the nation’s health care spending, while state and Federal spending account for 55 percent. Private health insurance alone comprises only 33 percent of expenditures. Basically, the public and private sectors have swapped positions.

Since government today is already responsible for more than half the health care spending in the United States, and private health insurance only one-third, even economic conservatives must now ask themselves: Why fuss over that last third? Why not simply inject government into it and be done? Is it because private health insurance is a symbol of free-market capitalism? Why fuss over a symbol? Besides, for many low- and middle-income people, it’s a very expensive symbol.

The sheer existence of the private health insurance market allows for the practice known as “cost-shifting,” whereby people with private insurance pay more for their services to compensate for the low rate of reimbursement from Medicare and Medicaid. This hurts low- and middle-income people during their working years. Even more irksome, the co-existence of public and private insurance lets policymakers play games with low- and middle-income workers, with scattershot tax credits and subsidies hurting some workers to benefit others, depending on where they work and what businesses they work for, while the very rich and the very poor stand happily on the sidelines. Although the ACA exemplifies this, Congressman Paul Ryan’s recent plan did some of the same. Middle-income workers would have suffered less financial pain than they do now under the ACA, but the plan’s refundable tax credits would have been insufficient to cover the insurance costs of low-income workers earning too much to qualify for Medicaid.5 Either way, some working people always end up being sacrificed for the benefit of others. Such games have gone on now for almost four decades.

We should insist on no more games. A main benefit of a national health insurance system is that it would rely on direct progressive taxation for funding. A person making $30,000 a year pays less toward his or her health insurance than a person making $50,000 a year, independent of where he or she works, how many hours he or she works, or how generous his or her employer is. Such a system is easy to understand, transparent, and fair. The United States needs to move away from its current work-based insurance premium system, with its Byzantine maze of credits and subsidies (whether ACA subsidies or free-market-oriented “premium support”), and simply tax people’s incomes or investment streams directly to pay for their insurance, with the rich paying more than the poor.

How that tax system is set up can be a subject for debate. Perhaps the poorest Medicaid recipients should pay nothing in taxes toward their insurance, or only, say, $5 a month. Perhaps a person making $40,000 annually should pay $100 a month, or $125. Perhaps a family making $500,000 a year should $28,000 annually, or $29,000 (which is more than they’re paying now for insurance). All this can be decided in due course. More important is to make paying for health insurance a straightforward progressive scheme through direct taxation, giving low and middle-income people relief from the economic shenanigans to which they have been so long exposed.

Now, implementing a national health insurance tax plan need not necessarily come with actual national health insurance: These are two very different things. Good reasons exist to preserve the private insurance system, including efficiency and greater responsiveness to consumer demands. If conservatives have won any argument over the past century it is that the private sector is usually more efficient and consumer-friendly than government is. I believe the private health insurance system should remain for these reasons. Instead of receiving their monies from a mixture of employers, employees, individuals, non-profits, and indirect government subsidies, private insurance companies can get them directly from the government, through taxes.

Precedent exists for this. The full-time Federal workforce hasn’t actually increased all that much over the past two decades. What has increased is the enormous number of subcontractors who perform government tasks. Private health insurance companies will simply become one more (albeit giant) contractor for the Federal government.

Nor does government’s role as check-cutter for the insurance companies necessarily risk inefficiency. Again, a century’s worth of experience has shown that government programs involving nothing more than cutting checks to stable populations (for example, Social Security sending money to seniors) work reasonably well. It is when government involves itself in the delivery of services, or in social engineering, that trouble arises. The insurance companies represent a kind of stable population.

To preserve the private insurance system’s stability, government needs to take one more action. It is well known that about 20 percent of the people account for 80 percent of the costs in health care. As a physician, I see this phenomenon play out all the time. For example, the same morbidly obese people come in for their diabetes checks, then a few years later come in for their cardiology checks (because their obesity and diabetes affect their cardiovascular systems), then the following year come in for their pulmonary checks (because their obesity causes sleep apnea), then the next year come in for their joint replacements (because their obesity stresses their joints), then a year later come in for their vascular bypass surgeries (because now their diabetes has clogged their blood vessels), then a year after that come in for their hysterectomies or breast biopsies, if they are female (because their obesity has led to abnormal estrogen levels, causing severe uterine bleeding or breast cancer), and so on. Other patients use health care constantly because they have particular diseases that give rise to systemic problems that need constant management—for example, patients with connective tissue disorders. Still others have exceedingly rare diseases that require expensive therapies—for example, people with hereditary diseases such as Wilson’s disease or hereditary angioedema.

Under the ACA, the younger and healthier subsidize these people by paying more for insurance than they otherwise would. This is unfair. They have their own lives to lead. Why should they be so burdened during the most hopeful period of life? Instead, the Federal government should take over direct payment of those health conditions that generate most of the costs, similar to what it did in the 1970s when Medicare took over payment of hemodialysis for patients with end-stage renal disease. This would involve essentially bifurcating the health insurance pool into an 80 percent chunk that can pay for itself quite well, and a 20 percent chunk that is hopeless in that respect and that combined with the 80 percent chunk makes everything hopeless. Monies for patients with such conditions (the conditions themselves can be debated) will come through direct progressive taxation, as they will for health insurance in general. Not only is this fair, it would also preserve the solvency of the private insurance system.

The ACA is failing because it expects the healthy to subsidize the unhealthy. The healthy exit the system by paying a fine, leaving insurance companies with the most expensive patients. Removing those patients from the private insurance system can stabilize the system. In a way, it is analogous to government removing subprime mortgages and other bad loans from a bank’s books to keep the bank afloat.

Health care reform invariably starts with economics. It always has, which is understandable. Money is a powerfully compelling reality. Health care is accessed via insurance, which is all about money. The problem with this approach shows up when policymakers must decide which economic issue to tackle first: the insurance problem or the health care cost problem? The choice on both sides of the political spectrum has typically been to solve the insurance problem first (meaning, decrease the number of uninsured) and then to control costs afterward. This is not surprising, since expanding insurance makes voters happy, while controlling costs through restrictions makes voters unhappy. We saw this during the 1990s, when managed care brought down the rate of increase in health care costs, but only temporarily, as patients (meaning voters) started to complain.

It is easy to understand politically why the Obama Administration approached the problem this way. But it is still the wrong approach. Health care costs should be brought under control first, or at least simultaneously, making the method by which we insure people—national health insurance versus private insurance—less important, since without cost control rationing is inevitable either way. And while controlling costs has an obvious economic component, it also has an equally important non-economic component. A serious personnel problem exists in medicine, begging for resolution. Once resolved, the potential cost savings are enormous. Then again, it must be resolved correctly, because otherwise patient lives will be endangered.

The problem begins with the doctors. Doctors no longer know what it means to be a doctor anymore, nor does anyone else in medicine. This confusion radiates outward, affecting every sector in health care. Is a doctor a technician? If so, should nurses and other para-professionals who are sometimes better than doctors at performing procedures be considered on par with doctors? How much authority should a doctor wield? In the new environment of patient-centered care, are doctors and patients equals? Is doctoring a profession or just a job? If just a job, does that mean doctors should work for a company?

This is just a slice of the confusion that now exists in medicine, as doctors fight with nurses over turf, fight with patients over who calls the shots, fight with employers who treat them like “line workers” in their companies, and fight with regulators who presume to govern their activities at a distance. Not only does this confusion demoralize physicians, it also arouses resentment among the various actors in medicine who feel themselves treated unjustly, or who bristle at what they believe to be an unfair usurpation of their rights. It is also dangerous for patients, because it spawns conflicts (and politics) in everyday medical care that risks trapping them in bad situations.

Disarray always arises when a system loses its core. No one knows who is in control, and so different people move in to take it. This poses new problems. The trend toward employed physicians that has continued under the ACA exemplifies this, with more than half of today’s doctors now working as dependent employees for large companies. As dependent employees, doctors must please both their customers (which is how today’s patient-centered care movement views patients) and their bosses, or risk being fired. As a consequence, doctors increasingly factor in numerous side considerations—often political—when making medical decisions, and some of these endanger patients. Policymakers who salivate over the potential cost savings from putting doctors on salary overlook this ominous trend.

The role of doctor needs to be redefined for the 21st century. I have described this new role as one of a “leader,” but whatever its title, the change means that doctors in the future (more in primary care than in the surgical specialties) must take on more supervisory duties, while ceding many of their traditional technical, diagnostic, and therapeutic activities to nurses, para-professionals, and computers.6 This should excite doctors, who risk becoming superfluous in a world where machines and other professionals can do much of their routine work as well as they can. Besides, doctors themselves are increasingly bored and frustrated with their work—for example, much of their time is devoted to entering data for the sake of electronic recordkeeping, turning them into information technologists. The new plan should excite nurses and other health care professionals, who will expand their scope of responsibilities beyond their current limited menu. And it should excite policymakers, for the potential cost savings are enormous.

For example, we now have a shortage of doctors. New medical schools are being built. Doctors and medical schools are expensive. But the shortage exists only if doctors retain their current role as the primary performers of procedures and the primary dispensers of drugs. If they do not, then the shortage evaporates, and so does the financial pressure.

Once the doctor’s role is established, much else falls into place—for example, what nurses do, what administrators do, what technicians do, how hospitals are organized, how many doctors we need and what kind, the difference between who practices in hospitals and who practices in outpatient centers, and so on. But—and this is most important—doctors and nurses, along with their governing boards, must sort these issues out themselves, working together, rather than have the answers imposed on them by impersonal policymakers and regulatory bodies. This points to another important cost-saving reform we must make.

Doctors and nurses often discuss among themselves the cost savings they could generate in everyday medical care, if only they were consulted. But they are rarely consulted. Medicare, other Federal agencies, and hospital accreditation bodies impose rules on them that often make no sense. Who are these rulemakers, doctors and nurses often ask themselves? Where and how do they come up with their rules? In my own specialty of anesthesiology, for example, we wonder why patients having cataract surgery under a few minutes of sedation must have the same physician coverage as patients getting brain surgery. We wonder why distinctions aren’t made between patients’ medical histories, allowing sicker patients in surgery to get a little more staffing support than healthy patients during their operations, without violating some rule. We wonder why agencies straitjacket doctors and nurses with rules mandating certain medicines always be given preoperatively, or that post-operative pain always be reduced to a particular level, thereby eliminating the flexibility doctors and nurses need in some situations.

The ACA is an example of such policymaker thinking on a grand scale, conceived at an unhealthy distance from everyday medical practice. It commanded, it ordered, and it mandated; it rarely consulted. To the degree that it made a cost-containment effort (and it wasn’t much) it was misguided and unnecessarily impolitic—for example, the future Medicare panels composed of unknown appointees who will decide how health care will be rationed. Again, these were orders coming from on high, from people with no real feel for patient care. Conservative health policy ideas often originate from analogous quarters, such as free-market economics departments or conservative public policy organizations. Health savings accounts (HSAs) exemplify this. They are a reasonable idea. With HSAs, patients decide whether to see a doctor or pocket the money as savings. But conservative activists, too, ignore the everyday human element in medicine. Do all patients have sufficient knowledge to make these decisions? No. What about children, who lack decision-making power, and their parents, who will be put in the untenable position of having to choose for them?

Health policy that originates in closed-off environments reminiscent of bank boardrooms is inherently unwise. Doctors and nurses know the ins and outs of medical practice better than anyone else. They know where the money is wasted in health care and where costs can be cut—safely. With their practical natures and vast clinical experience, they and not economists or ideologically driven public policy activists need to lead on reform. They need to review the regulations imposed on health care that are generating unnecessary costs. But no one lets them.

Skilled politicians are sensible. They know what goes on inside their constituents’ minds and are eager to take advantage of it. This makes the reforms described above doable. Both political parties know that people are angry with them, while also anxious about their health security. People are angry with the Democrats for creating the ACA. They are angry with the Republicans for failing to fix it. Both parties have a huge vested interest in solving this problem.

For Democrats, progressive tax plans work like catnip. Once the plan described above becomes the main funding stream for health insurance, they will probably work with Republicans on the second-order issues, despite their hostility toward President Trump. Republicans, in turn, will be able to finally deal with the health care problem that they have always looked upon nervously as “not their issue.”

The greater hurdle in reform is not the politicians but the credentialed policymakers—the vast army of health economists, health policy analysts, public health experts, and health management consultants—who control the debate over health care reform. For four decades, these people have shrouded themselves in mystery so as to preclude democratic interference. They have argued that health care is too intricate a matter to be entrusted to the ignorant masses. How could people without Ph.D.s be relied on to make judicious judgments about something so complex as health care, they ask? Indeed, “complex” is one of their favorite words. While health care is complex, their constant invocation of that word is designed to seal the process of health care reform off from common sense scrutiny and, above all, from the medical professionals who actually know what this is really all about.

The ideologues and policy technicians have failed. Four decades of repeated crises and mishaps prove this beyond all doubt. Fortunately, in the end, the politicians control the technicians, and they can include medical professionals in efforts toward real reform. The era of the health policy analyst is over. Let the era of the doctor and the nurse begin.

1Brad Tuttle, “Here’s What Happened to Health Care Costs in the Obama Years,” Money, October 4, 2016.

2Jeffrey Anderson, “The Real Number of Uninsured Americans,” Weekly Standard, December 29, 2010.

3Kimberly Amadeo, “How Much Did Obamacare Cost?” The Balance, March 27, 2017.

4See Nancy De Lew, “A Layman’s Guide to the U.S. Health Care System,” Health Care Finance Review (Fall, 1992), pp. 151-164. Also see “The Nation’s Health Dollar, Calendar Year 2015,” Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, National Health Statistics Group.

5Kate Leslie, “GOP Health Plan Means Millions More Uninsured,” Dallas Morning News, March 13, 2017.

6Ronald W. Dworkin, “What Is a Doctor?” National Affairs (Winter 2014).

Duterte Declares Martial Law In Mindanao

He’s been threatening to do it for a long time, and today he finally did: Rodrigo Duterte has declared martial law on Mindanao, as fighting heats up against Islamist militants on the Philippines’ second largest island. The Washington Post:

Presidential spokesman Ernesto Abella said in Moscow that martial law would be in effect on the entire island of Mindanao for 60 days.

The declaration of martial law was necessary “in order to suppress lawless violence and rebellion and for public safety,” Abella told reporters. “The government is in full control of the situation,” he added, but is “fully aware that the Maute/ISIS and similar groups have the capability, though limited, to disturb the peace.”

Lorenzana said martial law measures on Mindanao would include suspension of the writ of habeas corpus, the imposition of curfews and establishment of checkpoints.

Duterte’s order came after severe fighting in Marawi City, where Philippine troops were leading a raid to capture Isnilon Hapilon, the former Abu Sayyaf head who has emerged as the Islamic State’s head honcho in the Philippines. Hapilon has been working to unite disparate militant factions that have pledged loyalty to ISIS, including the Maute group formed in 2013 from members of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). And he seems to have had some success: according to early reports, it is the Maute group that has been on the frontlines in Marawi City. Eyewitness accounts tell of Maute militants taking over buildings, torching a school and jail, and hoisting ISIS flags through the streets as they clash in firefights with army troops.

To be clear, then, the threat in Mindanao is certainly serious. Duterte’s declaration is already raising concerns about his authoritarian tendencies, but the wider context should be taken into account. Islamic State has been making troubling inroads in Mindanao in recent years, seeking to co-opt homegrown militant factions that have long roiled the island—and that should cause no less concern than Duterte’s excesses.

In any case, Duterte’s declaration happened at an interesting moment: the Philippine president was in Moscow at the time, seeking to capitalize on promises to re-orient his foreign policy toward Russia and acquire weapons that the U.S. had denied him on human rights grounds. One wonders if the Russians might offer further security cooperation to help Duterte with his terrorism problem—and if the Trump Administration, far less concerned about human rights and far more eager to court Duterte than Obama was, might do likewise.

Pyongyang Revs Up Missile Work

After Pyongyang’s latest missile test this Sunday, the Wall Street Journal has taken the pulse of expert opinion on North Korea’s missile technology. And the outlook is grim, with Pyongyang making critical gains on multiple fronts far faster than many had expected:

While most U.S. policy makers remain concerned about North Korea’s ability to deliver a nuclear-tipped missile to the continental U.S., the speedy development of the Pukguksong-2, or the Polaris-2, highlights how quickly North Korea is mastering other critical missile technologies that are making Pyongyang a bigger threat to the U.S. military and its allies in East Asia.

The missile, while not designed to reach beyond most of the U.S. bases in South Korea and Japan, can be fired with almost no preparation time from the back of a mobile launcher, giving North Korea more stealth in its launches, as well as the ability to retaliate in the case of a strike against it, experts say. […]

The declaration of success with the Polaris-2, which the U.S. calls the KN-15, comes just a week after North Korea launched a new missile, the Hwasong-12—which experts say is capable of flying 2,800 miles, more than enough to reach the U.S. base in Guam and farther than any weapon that North Korea has successfully fired to date. Both the Polaris-2 and Hwasong-12 are capable of carrying nuclear warheads, North Korea says.

What happens when a can-kicking foreign policy approaches the end of the road? All the options get worse, yet the need to choose one grows.

The U.S. is coming ever closer to the binary choice of war with North Korea or acceptance that North Korea, despite decades of categorical U.S. threats and promises to allies that its nuclear drive will be halted, has succeeded in developing a nuclear capability that deters the U.S. from attacking it.

Single-Payer Is Less Appealing When it Comes With a Price Tag

Progressive lawmakers in California eagerly unveiled a plan for a state-run single-payer healthcare system, only to find that paying for it would require the state to more than double its tax burden (and that’s before the bureaucratic bloat and cost inflation kicks in). The San Francisco Chronicle reports:

Creating a single-payer health care system in California would cost $400 billion a year — including $200 billion in new tax revenue, according to an analysis of legislation released Monday by the Senate Appropriations Committee.

The projected cost far surpasses the annual state budget of $180 billion, and skeptics of the bill say the price tag is “a nonstarter.”

Yes, that’s right: A state-run insurance system would cost more than California spends on all other public services—education, police, pensions, and more—combined. The fiscal forecasts for New York’s proposed single-payer system are similar.

The GOP House’s haphazard efforts to repeal Obamacare would leave so many people without health insurance that they seem like political suicide. Meanwhile, the progressive approach to healthcare—steadily increasing subsidies on the way to single-payer—will crash against the reality of constrained public budgets.

Both visions run up against the same problem: Whether insurance is bought by private individuals or paid for by the government, healthcare simply costs too much. In the short run, we can argue about exactly how much insurance should be subsidized; in the long-run, the only way out of this trap is to find sustainable ways to bring down the price of delivery, whether through expanded federally-funded research initiatives, regulatory changes, targeted immigration policies, or tort reform. (And stay tuned for the two headline pieces in our upcoming print issue on this subject—online later this week.)

America is stuck in a bitter and seemingly-endless tug-of-war about who should pay for health insurance. But no matter who wins, America won’t be that much better off unless we can find a way to make care cheaper altogether.

Moving Towards the Battery Breakthrough

The energy world is seemingly always one or two technologies away from a paradigm shift. The pairing of hydraulic fracturing and horizontal well drilling set of the shale boom and helped bring prices down from their $100+ per barrel echelon to the $50 range they exist in today. The Next Big Thing in energy, environmentalists tell us, is renewable energy, and wind and solar prices are starting to fall far enough to make them competitive with fossil fuels (in certain places and under certain conditions) without subsidies.

But renewables have a critical structural flaw: they can only supply power when the sun is shining and the wind is blowing. That intermittency makes them incapable of toppling fossil fuels the key components of a national (or global) energy mix, but lest we depress greens too much, there is a solution—energy storage. At the moment, we lack the sort of cost-effective, commercially scalable battery technology necessary to help even out the stop-and-go supply tendencies of renewables, but as the FT reports, storage options have increased dramatically in recent years:

“In 2016 there was almost 1,100 megawatt hours of utility-scale energy storage commissioned. There has been a huge ramp-up in the past two years,” says Julia Attwood of Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF). BNEF’s figures cover all storage technologies but lithium-ion batteries are now the storage technology “to beat”, according to analysts. […]

While costs of batteries are coming down, [Sam Wilkinson of IHS Markit] acknowledges that in most cases “incentives are required” to expand the market for battery storage to help balance the grid. “Costs have come down dramatically but there is still a long way to go before they are going to be truly embedded everywhere in the grid and we’ll see huge volumes of them,” Mr Wilkinson says.

Of course, speaking in absolute terms, energy storage deployment is still just a tiny fraction of what it needs to be in order to complement even the relatively small amount of wind and solar farms our planet currently supports, let alone the quantities of renewable energy greens imagine is just around the corner.

It would be just as foolish, however, to dismiss the potential (no pun intended) of storage technology as it was to declare the arrival of “peak oil.” The shale boom has leveraged technological advances to completely remake the oil and gas industry landscape in less than ten years, and it’s not inconceivable that a battery breakthrough could produce a similar effect on the renewable energy industry.

National governments would be far better off devoting their time and effort to the research and development of these sorts of technologies, rather than using subsidies to keep the current crop of green energy options afloat. Unfortunately, it looks like the Trump administration wants to move in the opposite direction and cut funding to energy innovation programs. That’s a mistake.

May 23, 2017

Greek Creditors Stall on Debt Deal

Not so long ago, Greece signed on to a new round of austerity, leading to some breathless predictions that an agreement on debt relief, and an IMF agreement to finance Greece’s bailout, would be negotiated by the Eurogroup meeting on May 22.

Well, the day has come and gone, the IMF has still not come on board, and no debt deal is in sight. Financial Times:

Diplomats said that, although ministers held in-depth talks on maturity extensions for bailout loans, and other options for debt easing, more time would be needed to conclude a deal.

Dutch finance minister Jeroen Dijsselbloem, who chaired the meeting, said that the new target was to conclude the talks on June 15 — the next scheduled meeting of euro area finance ministers.

“I’m sure we can be successful if we take a little more time,” he said, stressing that it was still a priority for ministers to bring the IMF into the programme.

Kicking the can down the road is what Greece’s creditors do best, so this should come as no big surprise. Nor should it be a shock to learn who is behind the delay: German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schauble has been putting his foot down with the IMF, insisting that there should be no binding deal on debt relief before Greece’s bailout is concluded, and its reforms implemented, in summer 2018. In other words, this is a familiar game of chicken, as the IMF seeks a credible, upfront German commitment to Greek debt relief as a condition of joining the bailout, while Schauble pursues a “details later” deal to get the IMF on board without obligating Germany.

But there is a new wrinkle to this old dynamic: in the run-up to September’s elections in Germany, the debt relief issue has split the current CDU-SPD coalition. Schauble is now openly at odds with Foreign Minister Sigmar Gabriel, a Social Democrat who recently called for Germany to grant Greece debt relief and lamented that “German resistance” could derail a deal. Far from increasing pressure for Schauble to give ground, though, this could actually harden his position. Schauble’s tight-fisted stance is popular with German voters, after all, and the CDU is already trying to depict SPD as being fiscally irresponsible and soft on Greece.

The deadline for a deal has now shifted to June 15, while massive debt repayments loom for Greece in July. So time will soon tell who blinks—or whether a messy compromise can be worked out to kick this can further down the road.

Award-Winning Russian Director Detained, Theater Raided

At the Cannes Film Festival this year, Russian film director Andrey Zvyagintsev’s masterpiece Loveless is getting a rapturous welcome from critics. Meanwhile in Russia, a former Cannes winner, film and theater director Kirill Serebrennikov, is being hauled off for interrogation at the Investigative Committee, after security personnel raided both his apartment and the Moscow theater he runs, the Gogol-Center.

At 9 a.m. today, a group of investigators, accompanied by masked armed men (either Russian OMON officers or FSB troops, it’s unclear at time of writing) entered the Gogol-Center building in the center of Moscow. Actors rehearsing before the evening show and staff who happened to be present were herded into the theater hall, their cellphones were taken from them, and they were not allowed to leave. Serebrennikov was detained during the search of his home.

The Investigative Committee later revealed it was investigating a case of fraud and embezzlement, to the tune of 200 million rubles ($3,3 million), of Moscow city funds paid in 2011-2014 to Platform, an arts project Serebrennikov founded. Russian media are reporting that searches were conducted without a court warrant, under an “emergency measures” statute of the criminal code.

Serebrennikov is one of Russia’s most famous filmmakers. His film Playing the Victim won the Grand Prize at the first Rome Film Festival in 2006, and his most recent film, The Student, was nominated for the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival and won the Cannes special prize last year. He was appointed the head of the Gogol-Center in 2012. His appointment technically came after Vladimir Putin had switched seats with Dmitry Medvedev, but it was the byproduct of the political thaw that took place on Medvedev’s watch.

2010 and 2011 were years of particular cultural ferment in Russia, of which the experimental Platform project, which combined theater, dance, music and media, was a standout. The theater branch of Platform, Seventh Studio, became the basis for the Gogol-Center. Serebrennikov was appointed to run the Gogol-Center by Moscow’s Culture Minister Sergey Kapkov, who served from 2011 to 2015. A close associate of billionaire Roman Abramovich and a member of United Russia party, Kapkov nevertheless did a lot for culture and the arts in Moscow.

Under Serebrennikov’s, the Gogol-Center become one of the finest theaters in the country, and his fame grew beyond Russia’s borders. In 2014, his Seventh Studio’s staging of “The Metamorphosis” in the Theater National de Chaillot in Paris was warmly received.

Serebrennikov staged many provocative plays, something that did not go unnoticed by the increasingly authoritarian Putin regime. In 2013, investigators audited Serebrennikov’s productions of “the Pillow Man” and “Thugs”; the audit was initiated by a group of concerned citizens calling themselves the “Committee on Morality”.

Kirill Serebrennikov’s politics went beyond his work; he personally became involved in causes as well. He was a consistent presence at the Moscow rallies in 2011-2012, and at anti-war protests after the Crimea annexation; he signed an open letter petitioning for the release of the Pussy Riot girls from prison; he publicly spoke against the adoption ban Putin enacted in response to the Magnitsky Act; he has been a vocal advocate for LGBT rights. After the annexation of Crimea, Serebrennikov likened Russia’s behavior to “an impoverished thug who has lost his mind from despair”, and called the Kremlin’s defenders scared people who don’t want to know or decide anything.

Serebrennikov is currently being held as a “witness” in the case (as opposed to a “suspect” or an “accused person”—different categories in Russian law). His detention is either the result of political repression, or a hit against Sergey Kapkov, who has a lot of enemies. Or it could be a simple takeover of the Gogol-Center.

The last time a theater was taken over in Russia was in 2015, after the Novosibirsk Opera and Ballet staging of Wagner’s “Tannhauser” was picketed by Orthodox protesters for insulting Jesus Christ. The director of the opera was fired and replaced with Vladimir Kekhman, a businessman who made his fortune in the early 1990s in St. Petersburg importing bananas. (It just so happens that the seaport Kekhman was using for his bananas was also the main port of entry for cocaine smuggling.) It later turned out that the Orthodox protests were staged for the only reason: to get the theater head replaced.

The last time a theater director was arrested was in 1939, during Stalin’s Great Purge, when Vsevolod Meyerhold was detained for political reasons. He was executed the very next year. Though we’re probably not quite there yet with Putin’s regime, it’s worth remembering that Ukrainian film director Oleg Sentsov was convicted for terrorism under politically motivated false pretenses in 2015, and is still sitting in Russian prison.

Next Monday, Russian President Vladimir Putin is supposed to arrive in France for an impromptu visit with the newly-elected French President Emanuel Macron. The visit will take place right after this year’s Cannes winners are announced. With one Russian movie director close to receiving a prestigious award, while another, also a Cannes winner, is being interrogated by the siloviki, it’s an excellent time for all of us to ponder just what Putin’s regime has become.

One Belt, One Road, One Bluff

H

aving invited 29 world leaders to Beijing the other week to celebrate his Belt and Road Initiative, Chinese President Xi Jinping promised his audience more than $100 billion in new investment. Presidents and prime ministers from Russia’s Vladimir Putin to Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan were happy to jostle for photo ops with Xi as they sought to attract Chinese money for roads and bridges. But the initiative is a muddle—and not only because one clumsy translation (“one belt one road”) has been replaced, confusingly, by another (“Belt and Road Initiative”). The bigger problem is the substance.

There is a logic at the core of the Belt and Road—Asia needs more infrastructure—but thanks to jumbled strategic thinking and a suffocating amount of PR fluff, Xi’s flagship initiative looks set to disappoint. Asian and European countries lining up to attract Chinese investment in new roads and bridges will receive less money than the headline figures suggest. China itself will discover that lending money to its more poorly governed neighbors is not always a profitable business. And foreign policy analysts who see the Belt and Road as a Chinese-style Marshall Plan will be disappointed as the bubble of sky-high expectations pops. For the United States, there is little to fear in the Belt and Road. Asia may get some useful new roads, but the region will also see the limits of Chinese power projection, even in a sphere such as infrastructure where China has a comparative advantage.

The headline numbers associated with the Belt and Road are impressive, and purposefully so. Asia needs lots of infrastructure and an economic vision. China has an impressive track record building highways and high-speed trains across its own vast territory. With Washington distracted by domestic politics, Beijing rightly sees a chance to set the agenda in Asia. Hence the initiative, which was first launched in 2015, has been repeatedly expanded. Last weekend’s summit in Beijing demonstrated China’s ability to convene heads of state—at least when it is promising them vast sums of money.

But the gap between China’s promises and commitments are already being noticed. By some estimates, Chinese construction contracts with Belt and Road-related countries may decline in 2017. Already, officials in some neighboring countries are grumbling about not receiving money. Russia, for example, is miffed that that despite applying for funding for 40 different projects, it has yet to receive a dollar. This is despite the purported partnership between the two countries.

And Beijing’s mechanism for spending the money appears as likely to generate enemies as friends. For one thing, though small and medium-sized countries are lining up for cash, the region’s great powers are responding with counter initiatives. India, for example, boycotted the Belt and Road Forum and accused China’s lending program of benefitting Beijing more than its neighbors. Japan is pushing its own “quality infrastructure” initiative, emphasizing inadequacies in Chinese construction. Tokyo is also pushing to finalize the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade deal without the United States, which would give Japan a major role in writing Asia’s trade rules. And Russia, which itself hopes to participate in the Belt and Road, is eying Central Asia nervously. The Kremlin had long hoped it could divide the region, with Russia managing the politics and security, while China helped develop these countries’ economy. But as China’s role grows, that division of labor is looking more difficult to sustain.

Even in places where China’s influence is not being countered by other powers, Beijing’s massive cash infusions may still lead to headaches. Consider the over $20 billion Beijing has committed for the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, much of it on projects in the transport and energy spheres that are already underway. For Pakistan, this is a big opportunity. The country needs investment, and even though the financing terms and thus the ultimate cost to Pakistan are not clear, Islamabad is desperate for cash today. For China, the payoff is primarily geopolitical. Thanks to the project, Beijing is deepening Pakistan’s dependence, while increasing China’s access to the Indian Ocean and its energy trade routes via Pakistan’s port of Gwadar.

But will China’s loans to countries such as Pakistan ever get repaid? The history of development lending to countries such as Pakistan is full of disasters, conflicts, and painful defaults. Decades of experience from Western countries and institutions such as the IMF show that making loans is the easy part. It is far harder to ensure that money is used effectively, and more difficult still to guarantee that loans are paid back. Many of the countries receiving Belt and Road financing are not known for performing well on these metrics. Sri Lanka is already struggling to deal with debt from Chinese-backed infrastructure projects. And in a worrisome irony, former Pakistani Prime Minister Shaukat Aziz spoke at the Belt and Road forum emphasizing his experience in office restructuring his country’s foreign debt. That default is unlikely to be Pakistan’s last.

Beijing’s foreign policy credibility now depends on extending as many loans as possible. But the more money it lends now, the larger the future cost will be. China already has had to deal with spendthrift client states, for example by repeatedly extending its loans to Venezuela, which is on the brink of bankruptcy. But as external lending expands, the likelihood that China swallows the cost of defaults, as it has done with Venezuela, will decline.

If China tries to force repayment, however, it will lose friends quickly. Consider the IMF, which is reviled in many developing countries for demanding austerity measures to enforce loan repayment. Whenever lenders try to force repayment, relations sour. When they forgive the loans, they incur a large cost. With Belt and Road-related promises reaching around $1 trillion, the sums are substantial. The losses—Chinese officials privately estimate that certain projects will lose 80% of the money invested—may be large, too. Thus China is setting itself up either for significant losses or for painful battles with its neighbors over debt repayments. Notably, only 1% of Belt and Road funding has been extended via institutions such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, which have credible lending criteria. The bulk of Belt and Road loans have come through the China Development Bank and the country’s big-four state-owned banks, which at times act as slush funds for Beijing’s foreign policy. The financial viability of much of this lending is dubious at best.

The already underwhelming implementation and the likelihood of unpaid debts is not the only reason to expect that the Belt and Road will disappoint Beijing’s geopolitical goals. China is using the Belt and Road to export its excess capacity in heavy industries and construction. Yet what the world outside of China needs is not more supply of Chinese industries, but more demand from Chinese consumers. If China were to spend more on its consumers, they would buy more from abroad, increasing demand—and thus employment—in other countries. Instead, China is looking to build roads and bridges that will increase demand for Chinese concrete and steel—and which will in many cases be built by Chinese workers. The Belt and Road is as much a welfare program for Chinese industry as for the country’s poorer neighbors.

Already, however, other countries are beginning to realize this. U.S. President Donald J. Trump is not the only world leader complaining about Chinese trade practices, even if he wrongly focuses on the bilateral trade deficit rather than more relevant multilateral dynamics. Kenya’s president was only the most recent world leader to demand that China buy his country’s products in addition to its raw materials. The more that the Belt and Road succeeds in its current form, the bigger this problem—and, likely, the political backlash—will become. Already, neighbors such as Kazakhstan are imposing restrictions on Chinese laborers and investment in their countries to ensure they benefit, too.

At their forum in Beijing, the Chinese presented an image of a new order of international trade and investment. But the Belt and Road looks likely to repeat and intensify existing problems. There is no evidence that Beijing has a special formula to make development lending effective. Its current plans will create plenty of waste followed, in a decade, by disputes over repayment. China’s vast plans are already worrying other regional powers. Meanwhile, its decision to double down on its industrial and construction sectors by exporting overcapacity abroad will deepen disagreements about China’s trade. Particularly after the U.S. withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, many observers have interpreted the Belt and Road as a geopolitical masterstroke that will rewrite the rules of Asia. But the foreign policy benefits that China gains from the project will come with a high price—and will be counteracted by nervous reactions from slighted or frightened neighbors.

Peter L. Berger's Blog

- Peter L. Berger's profile

- 227 followers