Oxford University Press's Blog, page 999

December 7, 2012

De Quincey’s fine art

By Robert Morrison

Two hundred and one years ago this month, along the Ratcliffe Highway in the East End of London, seven people from two separate households were brutally murdered. News of the atrocities quickly spread throughout the country, generating levels of terror and moral hysteria that were not seen again until three-quarters of a century later when Jack the Ripper launched his savage career in a neighbouring East End district. Britain had no professional police force until 1829, and so the task of apprehending the killer (or killers) fell to an ill-coordinated group of magistrates, watchmen, and churchwardens who were woefully unprepared for the pressures of a major murder investigation, and who struggled to reassure a terrified populace that justice would be served. “We in the country here are thinking and talking of nothing but the dreadful murders,” wrote Robert Southey in December 1811, safe in his Keswick home three hundred miles from London, but still badly unnerved. “I…never had so mingled a feeling of horror, and indignation, and astonishment, with a sense of insecurity too.”

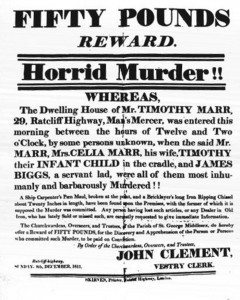

The killing began near midnight on Saturday, 7 December 1811, when an assassin passed quietly through the unlocked front door of Timothy Marr’s lace and pelisse shop. Once inside he bolted the door behind him and then ruthlessly dispatched all four inhabitants. When the alarm was raised and the door unlocked, eye-witnesses saw Marr’s wife Celia sprawled lifelessly. Marr himself was dead behind the store counter. His apprentice James Gowen was stretched out in the back near a door that led to a staircase. Downstairs in the kitchen, three-month-old Timothy Marr junior was found battered and dead. All four victims had their throats slashed. Twelve days later — again around midnight, again in the same East London area — it all happened a second time, on this occasion in the household of John Williamson, a publican. Williamson himself was found dead in the cellar. He had apparently been thrown down the stairs. His throat was cut. His wife Elizabeth and maid Anna Bridget Harrington were discovered on the main floor, their skulls bludgeoned and their throats slit.

Authorities quickly rounded up and interviewed dozens of people. One of them, John Williams, an Irish seaman in his late twenties, was questioned before the Shadwell magistrates on Christmas Eve, and then sent to Coldbath Fields prison to await further investigation. Suspicion grew as circumstantial evidence mounted against Williams, but before the magistrates could re-examine him, he hanged himself in his prison cell. The circumstances of his death were widely interpreted as a confession of guilt — much to the relief of some of the magistrates — and on New Year’s Eve Williams’s body was publicly exhibited in a procession through the Ratcliffe Highway before being driven to the nearest cross-roads, where it was forced into a narrow hole and a stake driven through the heart. Several officials, however, immediately raised doubts about Williams’s guilt, and in The Maul and the Pear Tree: The Ratcliffe Highway Murders (1971), P. D. James and T. A. Critchley conclude that Williams could not have acted alone, if he was involved at all, and that he may even have been murdered in his prison cell by those who were responsible, an eighth and final victim in the appalling tragedy.

Authorities quickly rounded up and interviewed dozens of people. One of them, John Williams, an Irish seaman in his late twenties, was questioned before the Shadwell magistrates on Christmas Eve, and then sent to Coldbath Fields prison to await further investigation. Suspicion grew as circumstantial evidence mounted against Williams, but before the magistrates could re-examine him, he hanged himself in his prison cell. The circumstances of his death were widely interpreted as a confession of guilt — much to the relief of some of the magistrates — and on New Year’s Eve Williams’s body was publicly exhibited in a procession through the Ratcliffe Highway before being driven to the nearest cross-roads, where it was forced into a narrow hole and a stake driven through the heart. Several officials, however, immediately raised doubts about Williams’s guilt, and in The Maul and the Pear Tree: The Ratcliffe Highway Murders (1971), P. D. James and T. A. Critchley conclude that Williams could not have acted alone, if he was involved at all, and that he may even have been murdered in his prison cell by those who were responsible, an eighth and final victim in the appalling tragedy.

To Thomas De Quincey, the finer points of the investigation mattered little. What impressed him was the audacity, brutality, and inexplicability of the crimes, and in his writings he returns over and over again to the Ratcliffe Highway, always attributing the murders solely to Williams, and exalting, ignoring, or altering details in order to exploit his deep and diverse response to the crimes. In his finest piece of literary criticism, “On the Knocking at the Gate in Macbeth” (1823), De Quincey introduces the satiric aesthetic that enables him to see Williams’s performance “on the stage of Ratcliffe Highway” as “making the connoisseur in murder very fastidious in his taste, and dissatisfied with any thing that has been since done in that line.” Yet De Quincey also peers uneasily into the mind of the killer in order to reflect on the psychology of violence. In Macbeth, he asserts, Shakespeare throws “the interest on the murderer,” where “there must be raging some great storm of passion — jealousy, ambition, vengeance, hatred — which will create a hell within him; and into this hell we are to look.”

Williams is also at the heart of De Quincey’s three essays “On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts.” In the first, published in 1827, De Quincey grazes the brink between horror and comedy as he argues with energetically ironic aplomb that “everything in this world has two handles. Murder, for instance, may be laid hold of by its moral handle… and that, I confess, is its weak side; or it may also be treated aesthetically…that is, in relation to good taste.” Twelve years later, in the second essay, he employs the same satiric topsy-turviness, but in this instance he inverts morality rather than suspending it. “For if once a man indulges himself in murder,” he observes coolly, “very soon he comes to think little of robbing; and from robbing he comes next to drinking and Sabbath-breaking, and from that to incivility and procrastination.” Finally, in the 1854 “Postscript,” De Quincey changes direction, returning fitfully to the black humour of the first two essays, but concentrating instead on impassioned representations of vulnerability and panic, and in particular on the horror of an unknown assailant descending on an urban household which is surrounded by unsuspecting neighbours. In its coherence, intensity, and detail, the “Postscript” is De Quincey’s most lurid investigation of violence.

The three “On Murder” essays had a remarkable impact on the rise of nineteenth-century decadence, as well as on crime, terror, and detective fiction. De Quincey is “the first and most powerful of the decadents,” declared G. K. Chesterton in 1913, and “any one still smarting from the pinpricks” of Oscar Wilde or James Whistler “will find most of what they said said better in Murder as One of the Fine Arts.” More recently, the British television drama Whitechapel (2012) has exploited De Quincey’s fascination with the Ratcliffe Highway killings, as have authors including Iain Sinclair, Philip Kerr, and Lloyd Shepherd. “May I quote Thomas De Quincey?” asks the murderer politely in Peter Ackroyd’s Dan Leno and the Limehouse Golem (1994). “In the pages of his essay ‘On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts’ I first learned of the Ratcliffe Highway deaths, and ever since that time his work has been a source of perpetual delight and astonishment to me.” Most compellingly, in his forthcoming thriller Murder as a Fine Art, David Morrell makes De Quincey the prime suspect in a series of copy-cat murders that terrify London in 1854. Morrell’s two detectives Ryan and Becker discover that De Quincey’s “Postscript” has just been published, and that in it “the Opium-Eater described Williams’s two killing sprees for fifty, astoundingly blood-filled pages — murders that by 1854 had occurred forty-three years earlier and yet were presented with a vividness that gave the impression the killings had happened the previous night.” De Quincey’s response to Williams ranged from gruesomely vivid reportage to brilliantly satiric high jinks and penetrating literary and aesthetic criticism. In his hands, violent crime became a subject which could be detached from social circumstances and then ironized, examined, and avidly enjoyed by generations of murder mystery connoisseurs and armchair detectives who enjoy the intellectual challenge, rapt exploration, and satiric safety of murder as a fine art.

The three “On Murder” essays had a remarkable impact on the rise of nineteenth-century decadence, as well as on crime, terror, and detective fiction. De Quincey is “the first and most powerful of the decadents,” declared G. K. Chesterton in 1913, and “any one still smarting from the pinpricks” of Oscar Wilde or James Whistler “will find most of what they said said better in Murder as One of the Fine Arts.” More recently, the British television drama Whitechapel (2012) has exploited De Quincey’s fascination with the Ratcliffe Highway killings, as have authors including Iain Sinclair, Philip Kerr, and Lloyd Shepherd. “May I quote Thomas De Quincey?” asks the murderer politely in Peter Ackroyd’s Dan Leno and the Limehouse Golem (1994). “In the pages of his essay ‘On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts’ I first learned of the Ratcliffe Highway deaths, and ever since that time his work has been a source of perpetual delight and astonishment to me.” Most compellingly, in his forthcoming thriller Murder as a Fine Art, David Morrell makes De Quincey the prime suspect in a series of copy-cat murders that terrify London in 1854. Morrell’s two detectives Ryan and Becker discover that De Quincey’s “Postscript” has just been published, and that in it “the Opium-Eater described Williams’s two killing sprees for fifty, astoundingly blood-filled pages — murders that by 1854 had occurred forty-three years earlier and yet were presented with a vividness that gave the impression the killings had happened the previous night.” De Quincey’s response to Williams ranged from gruesomely vivid reportage to brilliantly satiric high jinks and penetrating literary and aesthetic criticism. In his hands, violent crime became a subject which could be detached from social circumstances and then ironized, examined, and avidly enjoyed by generations of murder mystery connoisseurs and armchair detectives who enjoy the intellectual challenge, rapt exploration, and satiric safety of murder as a fine art.

Robert Morrison is Queen’s National Scholar at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario. He has edited our edition of Thomas De Quincey’s essays On Murder, and his edition of De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium-Eater and Other Writings is forthcoming with Oxford World’s Classics next year. Morrison is the author of The English Opium-Eater: A Biography of Thomas De Quincey, which was a finalist for the James Black Memorial Prize in 2010. His edition of Jane Austen’s Persuasion was published by Harvard University Press in 2011. His co-edited collection of essays, Romanticism and Blackwood’s Magazine: “An Unprecedented Phenomenon” is forthcoming with Palgrave. Read his previous blog post on John William Polidori and The Vampyre.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Newspaper illustration depicting the escape of John Turner from the second floor of the King’s Arms after he discovered the second murders December 1811. London Chronicle via Wikimedia Commons. (2) The Funeral of the Murdered Mr. and Mrs. Marr and infant Son. Published Dec 24, 1811 by G. Thompson No. 43 Long Lane, West Smithfield. London Chronicle via Wikimedia Commons. (3) Ratcliffe Highway Murders Reward poster offering 50 pounds for information on the murders of the Marr Family, December 1811, London Chronicle via Wikimedia Commons. (4) Procession to interment of John Williams. Published Jan’y 10 1812 by G Thomson no 45 Long Lane Smithfield. London Chronicle via Wikimedia Commons. (5) Book cover used with the author’s permission.

The post De Quincey’s fine art appeared first on OUPblog.

The discovery of Mars in literature

By David Seed

Although there had been interest in Mars earlier, towards the end of the nineteenth century there was a sudden surge of novels describing travel to the Red Planet. One of the earliest was Percy Greg’s Across the Zodiac (1880) which set the pattern for early Mars fiction by framing its story as a manuscript found in a battered metal container. Greg obviously assumed that his readers would find the story incredible and sets up the discovery of the ‘record’, as he calls it, by a traveler to the USA to distance himself from the extraordinary events within the novel. The space traveler is an amateur scientist who has stumbled across a force in Nature he calls ‘apergy’ which conveniently makes it possible for him to travel to Mars in his spaceship. When he arrives there, he discovers that the planet is inhabited. Since then, the conviction that beings like ourselves live on Mars has constantly fed writings about the planet. The American astronomer Percival Lowell was one of the strongest advocates of the idea in his 1908 book Mars as the Abode of Life and in other pieces, some of which were read by the young H.G. Wells. Mars had the obvious attraction of opening up new sensational subjects. Greg’s astronaut modestly describes his story as the ‘most stupendous adventure’ in human history. It also resembled a colony.

Although there had been interest in Mars earlier, towards the end of the nineteenth century there was a sudden surge of novels describing travel to the Red Planet. One of the earliest was Percy Greg’s Across the Zodiac (1880) which set the pattern for early Mars fiction by framing its story as a manuscript found in a battered metal container. Greg obviously assumed that his readers would find the story incredible and sets up the discovery of the ‘record’, as he calls it, by a traveler to the USA to distance himself from the extraordinary events within the novel. The space traveler is an amateur scientist who has stumbled across a force in Nature he calls ‘apergy’ which conveniently makes it possible for him to travel to Mars in his spaceship. When he arrives there, he discovers that the planet is inhabited. Since then, the conviction that beings like ourselves live on Mars has constantly fed writings about the planet. The American astronomer Percival Lowell was one of the strongest advocates of the idea in his 1908 book Mars as the Abode of Life and in other pieces, some of which were read by the young H.G. Wells. Mars had the obvious attraction of opening up new sensational subjects. Greg’s astronaut modestly describes his story as the ‘most stupendous adventure’ in human history. It also resembled a colony.

It’s no coincidence that the surge of Mars fiction coincided with the peak of empire, so by this logic the Red Planet is sometimes imagined as a transposed other country. Gustavus W. Pope’s Journey to Mars (1894) describes the voyage of an American spacecraft to a utopian world of sophisticated civilization and technology. The Martians encountered by the travelers are immediately identified as allies and one of the climactic moments in the novel comes when they fly the American flag during a naval parade. The narrator is almost moved beyond words by the spectacle:

My eyes filled with tears of joy when I thought that, the banner of liberty which waves o’er the land of the free and the home of the brave, honoured in every nation and on every sea of Earth’s broad domain, should have been borne through the trackless realms of space, amid that shining galaxy of orbs that wheel around the sun, and UNFOLD ITS BROAD STRIPES AND BRIGHT STARS OVER ANOTHER WORLD!

Pope’s description is unusual in presenting the Martians as so similar to the travelers that they project hardly any sense of the alien and, even more important, seem quite happy for America to take the lead in the course of civilization.

The most famous Mars novel from the turn of the twentieth century, H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds (1898), takes the British treatment of the Tasmanians as a notorious example of brutal imperialism and then simply reverses the terms. The invading Martians simply direct against the capital city of the British Empire the same crude logic of empire: we are technologically able to conquer you, so we will do so. What still gives an impressive force to Wells’ narrative is the journalistic care that he took to document the gradual collapse of England. Despite its army and navy, the state is helpless to resist the Martians and they are only defeated by the germs of Earth rather than by its technology.

The most famous Mars novel from the turn of the twentieth century, H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds (1898), takes the British treatment of the Tasmanians as a notorious example of brutal imperialism and then simply reverses the terms. The invading Martians simply direct against the capital city of the British Empire the same crude logic of empire: we are technologically able to conquer you, so we will do so. What still gives an impressive force to Wells’ narrative is the journalistic care that he took to document the gradual collapse of England. Despite its army and navy, the state is helpless to resist the Martians and they are only defeated by the germs of Earth rather than by its technology.

Cover of “Edison’s Conquest of Mars”, from 1898. Illustration by G. Y. Kauffman.

This story of collapse did not please the American astronomer Garrett P. Serviss, who immediately wrote a sequel, Edison’s Conquest of Mars. Rather than waiting passively for the Martians to return, as Wells warns they might in his coda, Serviss describes an expedition to conquer them on their home planet. Two steps have to be taken before this can be done. First, the American inventor Edison discovers the secrets of the Martians’ technology and devises a ‘disintegrator’, which will destroy its targets utterly. Secondly, the nations of the world have to chip in to the expedition with large donations. Serviss describes an amazingly unanimous global cooperation: “The United States naturally took the lead, and their leadership was never for a moment questioned abroad.” Put this narrative against the background of the USA taking over former Spanish colonies like Cuba and the Philippines, and Serviss’s narrative can be read as an idealized fantasy of America’s emerging imperial role in the world. Of course no conquest would be worthwhile if it came too easily and Serviss’s Martians aren’t the octopus-like creatures described by Wells, but instead represent human qualities and characteristics taken to inhuman lengths.

Empire was only one way of imagining Mars. It also offered itself as a hypothetical location for utopian speculation. This is how it functions in the Australian Joseph Fraser’s Melbourne and Mars (1889), whose subtitle — The Mysterious Life on Two Planets — indicates the author’s method of comparison. Similarly, Unveiling a Parallel, by Two Women of the West (1893), written by the Americans Alice Ingenfritz Jones and Ella Merchant, describes two alternative societies visited by a traveler from Earth. All Mars fiction tends to take for granted the technology of flight and the vehicle in this novel is an ‘aeroplane’, one of the earliest uses of the term. When the narrator lands on Mars he has no difficulty at all in adjustment or with the language, quite simply because Mars is not treated as an alien place so much as a forum for social change.

The most surprising characteristic of early Mars writing is its sheer variety. Sometimes the planet is imagined as a potential colony, sometimes as an alternative society, or as place for adventure. One of the strangest versions of the planet was given in the American natural scientist Louis Pope Gratacap’s 1903 book, The Certainty of a Future Life on Mars. The narrator’s father is a scientist researching into electricity and astronomy with a strong commitment to spiritualism. After he dies, the narrator starts receiving telegraphic messages from his father describing Mars as an idealized spiritual haven for the dead. It is typical of the period for Gratacap to combine science with religion in narrative that resembles a novel. Before we dismiss the idea of telegraphy here, it is worth remembering that the electrical experimenter Nikola Tesla published articles around 1900 on exactly this possibility of communicating electronically with Mars and other planets.

All the main early works on Mars are available on the web or have been reprinted. They make up a fascinating body of material which helps to explain where our perceptions of the Red Planet come from.

David Seed is Professor in the School of English, University of Liverpool. He is the author of Science Fiction: A Very Short Introduction.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday!

Oxford University Press’ annual Place of the Year competition, celebrating geographically interesting and inspiring places, coincides with its publication of Atlas of the World — the only atlas published annually — now in its 19th Edition. The Nineteenth Edition includes new census information, dozens of city maps, gorgeous satellite images of Earth, and a geographical glossary, once again offering exceptional value at a reasonable price. Read previous blog posts in our Place of the Year series.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: War of the Worlds’ 1st edition cover.

The post The discovery of Mars in literature appeared first on OUPblog.

Does the state still matter?

By Mark Bevir

Governance, governance everywhere – why has the word “governance” become so common? One reason is that many people believe that the state no longer matters, or at least the state matters far less than it used to. Even politicians often tell us that the state can’t do much. They say they have no choice about many policies. The global economy compels them to introduce austerity programs. The need for competitiveness requires them to contract-out public services, including some prisons in the US.

If the state isn’t ruling through government institutions, then presumably there is a more diffuse form of governance involving various actors. So, “governance” is a broader term than “state” or “government”. Governance refers to all processes of governing, whether undertaken by a government, market, or network, whether over a family, corporation, or territory, and whether by laws, norms, power, or language. Governance focuses not only on the state and its institutions but also on the creation of rule and order in social practices.

Martin Schulz, President of the European Parliament

The rise of the word “governance” as an alternative to “government” reflects some of the most important social and political trends of recent times. Social scientists sometimes talk of the hollowing-out of the state. The state has been weakened from above by the rise of regional blocs like the European Union and by the global economy. The state has been weakened from below by the use of contracts and partnerships that involve other organizations in the delivery of public services. Globalization and the transformation of the public sector mean that the state cannot dictate or coordinate public policy. The state depends in part on global, transnational, private, and voluntary sector organizations to implement many of its policies. Further, the state is rarely able to control or command these other actors. The state has to negotiate with them as best it can, and often it has little bargaining power.

But, although the role of the state has changed, these changes do not necessarily mean that the state is less important. An alternative perspective might suggest that the state has simply changed the way it acts. From this viewpoint, the state has adopted more indirect tools of governing but these are just as effective – perhaps even more so – than the ones they replaced. Whereas the state used to govern directly through bureaucratic agencies, today it governs indirectly through, for example, contracts, regulations, and targets. Perhaps, therefore, the state has not been hollowed-out so much as come to focus on meta-governance, that is, the governance of the other organizations in the markets and networks that now seem to govern us.

The hollow state and meta-governance appear to be competing descriptions of today’s politics. If we say the state has been hollowed out, we seem to imply it no longer matters. If we say the state is the key to meta-governance, we seem to imply it retains the central role in deciding public policy. Perhaps, however, the two descriptions are compatible with one another. The real lesson of the rise of the word “governance” might be that there is something wrong with our very concept of the state.

All too often people evoke the state as if it were some kind of monolithic entity. They say that “the state did something” or that “state power lay behind something”. However, the state is not a person capable of acting; rather, the state consists of various people who do not always not act in a manner consistent with one another. “The state” contains a vast range of different people in various agencies, with various relationships acting in various ways for various purposes and in accord with various beliefs. Far from being a monolithic entity that acts with one mind, the state contains within it all kinds of contests and misunderstandings.

Descriptions of a hollow state tell us that policymakers have actively tried to replace bureaucracies with markets and networks. They evoke complex policy environments in which central government departments are not necessarily the most important actors let alone the only ones. Descriptions of meta-governance tell us that policymakers introduced markets and networks as tools by which they hoped to get certain ends. They evoke the ways central government departments act in complex policy environments.

When we see the word “governance”, it should remind us that the state is an abstraction based on diverse and contested patterns of concrete activity. State action and state power do not fit one neat pattern – neither that of hollowing-out or meta-governance. Presidents, prime ministers, legislators, civil servants, and street level bureaucrats can all sometimes make a difference, but the state is stateless, for it has no essence.

Mark Bevir is a Professor of Political Science at the University of California, Berkeley. He is the author of several books including Governance: A Very Short Introduction (2012) and The State as Cultural Practice (2010). He is also the editor or co-editor of 10 books, including a two volume Encyclopaedia of Governance (2007). He founded the undergraduate course on ‘Theories of Governance’ at Berkeley and teaches a graduate course on ‘Strategies of Contemporary Governance’.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday!

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: Martin Schulz during the election camapign in 2009. Creative Commons Licence – Mettmann. (via Wikimedia Commons)

The post Does the state still matter? appeared first on OUPblog.

December 6, 2012

Why we are outraged: the New York Post photo controversy

A New York Post photographer snaps a picture of a man as he is pushed to his death in front of a New York City subway. An anonymous blogger photographs a dying American ambassador as he is carried to hospital after an attack in Libya. Multiple images following a shooting at the Empire State Building show its victims across both social media and news outlets. A little over three months, three events, three pictures, three circles of outrage.

The most recent event involved a freelancer working for the New York Post who captured an image of a frantic Queens native as he tried futilely to escape an approaching train. Depicting the man clinging to the subway platform as the train sped toward him, the picture appeared on the Post’s front cover. Within hours, observers began deriding both the photographer and the newspaper: the photographer, they said, should have helped the man and avoided taking a picture, while earlier photos by him were critiqued for being soft and of insufficient news value; the newspaper, they continued, should not have displayed the picture, certainly not on its front cover, and its low status as a tabloid was trotted out as an object of collective sneering.

We have heard debates like this before — when pictures surfaced surrounding the deaths of leaders in the Middle East, the slaying of Vietnamese soldiers and civilians, the shattering of those imperiled by numerous natural disasters, wars and acts of terror. Such pictures capture the agony of people facing their deaths, depicting the final moment of life in a way that draws viewers through a combination of empathy, voyeurism, and a recognition of sheer human anguish. But the debates that ensue over pictures of people about to die have less to do with the pictures, photographers or news publications that display them and more to do with the unresolved sentiments we have about what news pictures are for. Decisions about how best to accommodate pictures of impending death in the difficult events of the news inhabit a sliding rule of squeamishness, by which cries of appropriateness, decency and privacy are easily tossed about, but not always by the same people, for the same reasons or in any enduring or stable manner.

Pictures are powerful because they condense the complexity of difficult events into one small, memorable moment, a moment driven by high drama, public engagement, the imagination, the emotions and a sense of the contingent. No surprise, then, that what we feel about them is not ours alone. Responses to images in the news are complicated by a slew of moral, political and technological imperatives. And in order to show, see and engage with explicit pictures of death, impending or otherwise, all three parameters have to work in tandem: we need some degree of moral insistence to justify showing the pictures; we need political imperatives that mandate the importance of their being seen; and we need available technological opportunities that can easily facilitate their display. Though we presently have technology aplenty, our political and moral mandates change with circumstance. Consider, for instance, why it was okay to show and see Saddam Hussein about to die but not Daniel Pearl, to depict victims dying in the Asian tsunami but not those who jumped from the towers of 9/11. Suffice it to say that had the same picture of the New York City subway been taken in the 1940s, it would have generated professional acclaim, won awards, and become iconic.

At a time in which we readily see explicit images of death and violence all the time on television series, in fictional films and on the internet, we are troubled by the same graphic images in the news. We wouldn’t expect our news stories to keep from us the grisly details of difficult events out there in the world. We should expect no less from our news pictures.

Barbie Zelizer is the Raymond Williams Chair of Communication and the Director of the Scholars Program in Culture and Communication at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania. She is the author of About to Die: How News Images Move the Public.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only media articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Why we are outraged: the New York Post photo controversy appeared first on OUPblog.

Mars and music

By long tradition, sweet Venus and mystical Neptune are the planets astrologically connected with music. The relevance of Mars, “the bringer of war” as one famous composition has it, would seem to be pretty oblique. Mars in the horoscope has to do with action, ego, how we separate ourselves off from the world; it is “the fighting principle for the Sun,” in the words of famous astrologer Liz Greene. Michel Gauquelin, who conducted a statistical test for the validity of astrology, found that Mars near the ascendant or midheaven in a person’s chart correlated heavily with choosing athletics or surgery as a career: it connects to physical competition and knives. Mars also rules everything military, and thus in music it is associated mainly with percussion. Most composers have egos, but musicians are not generally a physically aggressive bunch, and fighting isn’t our area. Many a famous composer sat out World War II playing in the Army band. (In high school I was thrilled that my simply taking music classes exempted me from the gym requirement — under the institutional assumption that all music students would get enough exercise in the marching band. I was a pianist.)

Claudio Monteverdi

And so Mars, in the classical music world, has been only an occasional acquaintance. There isn’t much classical music about athletics, though Arthur Honegger did write a rather punchy tone poem called Rugby (1928), and Charles Ives — a star baseball player in youth — portrayed a Yale-Princeton Football Game in music around 1899 as a kind of college prank. Music specifically about surgery may have yet to appear (and let’s leave Salomé out of this). Seeking a connection between Mars and music, Gustav Holst would probably leap to most minds, but I think first of Claudio Monteverdi. Holst, after all, had to give all his planets equal treatment, but it was Monteverdi who invented the “stile concitato,” the agitated style, to restore in music what he saw as a warlike mode known in poetry but historically absent in music. He made his theories explicit in his scenic cantata Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda of 1624, its poem a kind of forced sexual encounter disguised as a battle between armed rivals. Monteverdi makes it quite clear what he considered warlike tones: lots of quick repeated notes in a harmonic stasis. And if you think about it, that description applies equally well to “Mars” from Holst’s Planets (1914–16), with its hammering, one-note ostinato, and, as we’ll see below, to most other battle pieces as well. Considering the phenomenal evolution of the actual military, its musical signifiers have remained strikingly consistent.Despite Monteverdi’s continued advocacy in some subsequent Madrigali guerrieri of 1638, the stile concitato did not establish itself as a broad genre. In the centuries following Il combattimento, depiction of martial action is rare enough in music for the well-known instances to be easily enumerated. The first of Johann Kuhnau’s Biblical History sonatas (1700) purports to describe David’s conflict with Goliath, once again with a profusion of quick repeated notes; also with “martial” rhythms such as streams of dotted eighths followed by sixteenths, or the snare-drum rhythm of an eighth and two sixteenths. The Battalia a 9 (1673) of Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber is for only strings, but it too makes a fetish of chords in repeated notes. Its “Der Mars” movement, in addition, brilliantly asks for a piece of paper between the fingerboard and strings of the cello to make the instrument’s rhythmic drone sound plausibly like some kind of drum. Michel Corrette’s Combat Naval from his Harpsichord Divertimento No. 2 (1779) likewise starts off with repeated notes in snare-drum rhythms, and climaxes with forearm clusters that quite effectively signify cannon blasts. In Mozart’s and Haydn’s generations, even the presence of drums and cymbals was enough to suggest Turkish and thus military connotations (since what were the Turks there for, except to make war with?), as in Haydn’s “Military” Symphony, No. 100.

The advent of Romanticism, though, marked a turn at which war became demoted as a subject for serious musical treatment. Two of the 19th century’s most high-profile musical depictions — Beethoven’s Wellington’s Victory (1813) and Liszt’s Hunnenschlacht (1857) — are considered among their most embarrassingly literal and superficial works. Bruckner did claim that the Plutonian finale of his Eighth Symphony (1887) depicted two emperors meeting on the field of battle, but that was rather after the fact, since he was trying to throw his lot in among the programmaticists. All this suggests, I think, distinct unease among classical musicians with things military or violent. Of course military music is sometimes appropriated to good effect, as in Berlioz’s Rakoczy March from The Damnation of Faust (1846). But despite Monteverdi’s heroic attempt to establish a martial mode, in retrospect classical attempts to depict battle tend to become anomalous oddities from history (Corrette, Biber) or humorous superficialities (Beethoven, Liszt).

Carl Nielsen

Finally, in the 20th century, the increase in dissonance and percussion brought at least a more respectable realism to battle music, though the carnage of the World Wars made anti-war statements more popular than celebrations of famous victories. Carl Nielsen’s Fifth Symphony (1922) was a powerful response to the lunacy of World War I, with a first movement in which a solo snare drum seems determined to halt the progress of the orchestra, whose humanistic main theme finally overwhelms it. A couple of conflagrations later, Stravinsky made an anti-war statement in his Symphony in Three Movements (1945), partly inspired by film images of goose-stepping Nazi soldiers. Less ironically, George Antheil cheered the Allies along with his Fifth Symphony, subtitled “1942” and written that year as the fortunes of war were changing in North Africa. Shostakovich, in his Leningrad Symphony (1941), wrote melodies to symbolize the mutual approaches of the German and Russian armies, though the German theme is arguably a rather silly one; at least, Béla Bartók took savage delight in satirizing it in his Concerto for Orchestra. During the war even the more abstract-leaning Stefan Wolpe wrote a Battle Piece (1943-7) for piano — once again marked by repeated notes.The massive War Requiem (1961-2) by the pacifist Benjamin Britten, however — perhaps its century’s grandest anti-war musical protest, filled with snare-drum march rhythms and trumpet fanfares suspended in uneasy irony — seems to close a curved trajectory that opened with Monteverdi’s Il combattimento. Whereas musicians once thought the military mode in music could be innocently brought up with historical interest or patriotic pride, today we invoke it only to condemn it. The Vietnam War era may have rendered any non-pejorative expression of Mars verboten for the foreseeable future. In recent years the pianist Sarah Cahill commissioned anti-war pieces from many composers (Frederic Rzewski, Terry Riley, Pauline Oliveros, and Meredith Monk among them) for a project called “A Sweeter Music”; my own contribution, War Is Just a Racket, uses a 1933 text by General Smedley Butler, lamenting the army’s too-close ties to corporate interests.

Yet perhaps because Mars and Neptune were conjunct when I was born, I’ve written one un-ironic piece of battle music myself. Aside from the “Mars” movement of my own Planets (yes, I was foolhardy enough to compete with Holst, but my “Mars” is more complaining than belligerent), I depicted the battle of the Little Bighorn in my one-man electronic cantata Custer and Sitting Bull (1999), replete with sampled gunfire. The Sioux warriors are in one key, the US Cavalry in another a tritone away, and as they take turns the music jumps between two different tempos. But there’s something so peculiar about the expression of Mars in music that I have to wonder if, a couple of centuries from now, that battle scene will survive only as a curious anomaly, like Battalia a 9 or the Combat Naval or the battle of David and Goliath.

Kyle Gann is a composer who writes books about American music, including, so far; The Music of Conlon Nancarrow; American Music in the Twentieth Century; Music Downtown: Writings from the Village Voice; No Such Thing as Silence: John Cage’s 4’33”; Robert Ashley; and, coming up in 2015, a book on Ives’s Concord Sonata. His music explores tempo complexity and microtonality. He writes the blog, Postclassic and teaches at Bard College.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Oxford University Press’ annual Place of the Year, celebrating geographically interesting and inspiring places, coincides with its publication of Atlas of the World – the only atlas published annually — now in its 19th Edition. The Nineteenth Edition includes new census information, dozens of city maps, gorgeous satellite images of Earth, and a geographical glossary, once again offering exceptional value at a reasonable price. Read previous blog posts in our Place of the Year series.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Mars and music appeared first on OUPblog.

Ten things you didn’t know about Ira Gershwin

Today marks the 116th anniversary of the birth of Ira Gershwin, lyricist and brother to composer George Gershwin. There are many fascinating details about Ira, ten of which are collected here.

1. When Ira was growing up, he held a lot of odd jobs, one of which was shipping clerk at the B. Altman department store housed in the same building where today Oxford University Press has its offices.

2. Ira loved to play Scrabble. In one game he triumphed by using all seven of his letters to spell out CHOPSUEY. I don’t know which letter was already on the board that he built upon.

3. One of Ira’s neighbors on Maple Drive in Beverly Hills was Angie Dickinson, then at the height of her success with television’s “Police Woman.” Angie was a good poker player and frequently joined the poker games at Ira’s house with the likes of Harold Arlen (“Over the Rainbow”), Arthur Freed (“Singin’ in the Rain”), and other prominent songwriters. At the time, she said, she didn’t realize what august company she was in — still, she frequently cleaned the old boys out. She also learned what a stickler Ira was for grammar. After he had lost a lot of money to her, she said, “Ira, I feel badly that you lost so much.” Ira snapped, “Would you feel ‘goodly’ if I had won?”

4. Ira was also a stickler for proper pronunciation. It annoyed him if someone said “Ca-RIB-be-an” instead of “CA-rib-BE-an.”

5. So it annoyed him when singers took upon themselves to “correct” his deliberate grammatical and pronunciation errors — singing “I’ve Got Rhythm” instead of “I Got Rhythm,” “It’s Wonderful” instead of “‘S Wonderful,” “The Man Who Got Away” instead of “The Man That Got Away.”

6. Ira admired Dorothy Fields as a lyricist, the one woman among that tight-knit group of male songwriters, but he thought it was unforgivable that she playfully distorted the proper accent of “RO-mance” in “A Fine Ro-mance (my friend this is, a fine Ro-mance with no kisses…)”

7. Ira loved all sorts of verbal play. He once built an entire lyric out of “spoonerisms,” named after a British clergyman who loved the reversal of syllables that produces “The Lord is a shoving leopard” instead of “The Lord is a loving shepherd.” Technically such reversals are termed “metathesis” (which can be “spoonered” into “methasetis”). In The Firebrand of Florence Ira concocted such hilarious spoonerisms as “I know where there’s a nosy cook (instead of “cozy nook”)… where we can kill and boo (instead of “bill and coo”)… I love your sturgeon vile (instead of “I love your virgin style”).

8. Three of Ira Gershin’s lyrics were nominated for the Academy Award for Best Song: “They Can’t Take That Away from Me,” “Long Ago and Far Away,” and “The Man That Got Away.” All three lost. Ira decided it was because he had used the word “away” in the title and vowed “Away with ‘Away’!”

9. In London, he attended a rehearsal for a revue of Gershwin songs. Backstage, one of the English singers said she simply did not understand his lyric for “Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off.” When Ira asked what the problem was, she sang, “You say eye-ther and I say eye-ther, you say nye-ther and I say nye-ther…” then said “I just don’t get it, Mr. Gershwin.”

10. He had friends over for cocktails one afternoon and someone suggested they all go for dinner at a prominent restaurant in Beverly Hills. Ira offered to call and see if he could get a table for all of them. He came back to say he could not get a reservation because the restaurant was booked. One of his friends asked to use his phone and came to say he had gotten a table for the entire group that would be ready in a few minutes. When Ira asked how he was able to do that, the friend said, “I used your name.”

Philip Furia is a professor in the Department of Creative Writing at the University of North Carolina Wilmington. He is the author of The Songs of Hollywood (with Laurie Patterson), Ira Gershwin: The Art of the Lyricist, and The Poets of Tin Pan Alley.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Ten things you didn’t know about Ira Gershwin appeared first on OUPblog.

Secession: let the battle commence

There has rarely been a more interesting time to study secession. It is not just that the number of separatist movements appears to be growing, particularly in Europe, it is the fact that the international debate on the rights of people to determine their future, and pursue independence, seems to be on the verge of a many change. The calm debate over Scotland’s future, which builds on Canada’s approach towards Quebec, is a testament to the fact that a peaceful and democratic debate over separatism is possible. It may yet be the case that other European governments choose to adopt a similar approach; the most obvious cases being Spain and Belgium towards Catalonia and Flanders.

However, for the meanwhile, the British and Canadian examples remain very much the exception rather than the rule. In most cases, states still do everything possible to prevent parts of their territory from breaking away, often using force if necessary.

It is hardly surprising that most states have a deep aversion to secession. In part, this is driven by a sense of geographical and symbolic identity. A state has an image of itself, and the geographic boundaries of the state are seared onto the consciousness of the citizenry. For example, from an early age school pupils draw maps of their country. But the quest to preserve the borders of a country is rooted in a range of other factors. In some cases, the territory seeking to break away may hold mineral wealth, or historical and cultural riches. Sometimes secession is opposed because of fears that if one area is allowed to go its own way, other will follow.

For the most part, states are aided in their campaign to tackle separatism by international law and norms of international politics. While much has been made of the right to self-determination, the reality is that its application is extremely limited. Outside the context of decolonisation, this idea has almost always taken a backseat to the principle of the territorial integrity of states. This gives a country fighting a secessionist movement a massive advantage. Other countries rarely want to be seen to break ranks and recognise a state that has unilaterally seceded.

When a decision is taken to recognise unilateral declarations of independence, it is usually done by a state with close ethnic, political or strategic ties to the breakaway territory.Turkey’s recognition of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus and Russia’s recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia are obvious examples. Even when other factors shape the decision, as happened in the case of Kosovo, which has been recognised by the United States and most of the European Union, considerable effort has been made by recognising states to present this as a unique case that should be seen as sitting outside of the accepted boundaries of established practice.

However, states facing a secessionist challenge cannot afford to be complacent. While there is a deep aversion to secession, there is always the danger that the passage of time will lead to the gradual acceptance of the situation on the ground. It is therefore important to wage a concerted campaign to reinforce a claim to sovereignty over the territory and prevent countries from recognising – or merely even unofficially engaging with – the breakaway territory.

At the same time, international organisations are also crucial battlegrounds. Membership of the United Nations, for example, has come to be seen as the ultimate proof that a state has been accepted by the wider international community. To a lesser extent, participation in other international and regional bodies, and even in sporting and cultural activities, can send the same message concerning international acceptance.

The British government’s decision to accept a referendum over Scotland’s future is still a rather unusual approach to the question of secession. Governments rarely accept the democratic right of a group of people living within its borders to pursue the creation of a new state. In most cases, the central authority seeks to keep the state together; and in doing so choosing to fight what can often be a prolonged campaign to prevent recognition or legitimisation by the wider international community.

James Ker-Lindsay is Eurobank EFG Senior Research Fellow on the Politics of South East Europe at the European Institute, London School of Economics and Political Science. He is the author of The Foreign Policy of Counter Secession: Preventing the Recognition of Contested States (2012) and The Cyprus Problem: What Everyone Needs to Know (2011), and a number of other books on conflict, peace and security in the Balkans and Eastern Mediterranean.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only articles on law and politics on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Secession: let the battle commence appeared first on OUPblog.

December 5, 2012

In memoriam: Dave Brubeck

I first met Dave Brubeck when I was in my twenties, and writing my book on West Coast jazz. Dave deeply impressed me, and not just as a musician. How many celebrities have a marriage that lasts 70 years? I think Dave is the only one. He was a very caring family man, a good dad and husband – never a given in the entertainment industry. He was a pioneer on civil rights, threatening to cancel concerts when faced with complaints about his integrated band. He served his country as a soldier (at the Battle of the Bulge) and as both an official and unofficial ambassador. When Reagan met Gorbachev, Dave Brubeck was there, bringing people together with his music. I’ve talked to many of his friends over the years, and they tell stories of his kindness and loyalty. You could a learn a lot from Dave Brubeck just by watching how he conducted himself offstage. And then there is the public side of his music career, with all those concerts and recordings that reached tens of millions of people. I was privileged to know him, but many who simply experienced his artistry through his music will also miss him and grieve at his passing. God bless you, Dave!

Dave Brubeck

6 December 1920 – 5 December 2012

Dave Brubeck Quartet at Congress Hall Frankfurt/Main (1967). From left to right: Joe Morello, Eugene Wright, Dave Brubeck and Paul Desmond. GNU Free Documentation License via Wikimedia Commons user dontworry.

Ted Gioia is a musician, author, jazz critic and a leading expert on American music. His books The History of Jazz and Delta Blues were both selected as notable books of the year in The New York Times. He is also the author of The Jazz Standards: A Guide to the Repertoire, West Coast Jazz, Work Songs, Healing Songs and The Birth (and Death) of the Cool.

The post In memoriam: Dave Brubeck appeared first on OUPblog.

Oh, what lark!

For some time I have fought a trench war, trying to prove that fowl and fly are not connected. The pictures of an emu and an ostrich appended to the original post were expected to clinch the argument, but nothing worked. A few days ago, I saw a rafter of turkeys strutting leisurely along a busy street. Passersby were looking on with amused glee while drivers honked. The birds (clearly, “fowl”) crossed the road without showing the slightest signs of excitement (apparently, after Thanksgiving they had nothing to worry about), though two or three accelerated their pace somewhat. Not a single one flew. This convinced me that my theory was correct, and I decided to stay for a while in the avian kingdom; hence lark.

One of the Old English forms of lark was læwerce (with long æ), later laferce. Its West Germanic (Frisian, Dutch, and German) cognates resemble læwerce more or less closely. Modern Scots laverock and Dutch leeuwerk, unlike Engl. lark and German Lerche, have retained more flesh. The contraction of læwerce to lark should cause no surprise, because v from f was regularly lost between vowels: for example, head goes back to heafod, and hawk to hafoc. The protoform of lark must have sounded approximately like laiwazakon (-on is an ending). Obviously, such a long word must either have been a compound or made up of a root and a suffix. Attempts to discover two meaningful elements in laiwazakon began with our first English etymologist John Minsheu (1617). He detected leef-werck “life work” in lark, “because this bird flies seven sundrie times every day very high, so sings hymnes and songs to the Creator, in which consists the lives worke.” No one has ever repeated this etymology. But the search for the elements in the allegedly disguised compound continued.

Old (and Modern) Icelandic lævirki “lark” provided the greatest temptation. The word falls into two parts: læ- “treason, deceit” and virki “work.” It is not quite clear whether the Scandinavians borrowed their name of the lark from the south or whether we are dealing with a genuine cognate. In any case, lævirki is transparent. Unfortunately, too transparent, and it is surprising that Skeat let himself be seduced by such a hoax. He suggested that, according to some unknown superstition, the lark might be a bird of ill omen or, conversely, a revealer of treachery. The OED followed Skeat with a few minor modifications, and Skeat ended up with the tentative gloss lark “skillful worker, or worker of craft” (because læ sometimes meant “craft”; however, it hardly ever lacked the connotations of wiles). I think the time has come to forget it. Icelandic lævirki is the product of folk etymology: an opaque word acquired a deceptively clear shape (compare Engl. asparagus becoming sparrow grass, though everybody knows that sparrows are not herbivorous creatures). Dutch leeuwerk begins with leeuw “lion,” but no one would reconstruct a lost story in which a lark entertained a lion with its songs.

Two features of the lark are especially noticeable to humans: it is an early bird (whence its association with daybreak), and its songs (trills) are loud and melodious (after reading this post, listen to the recordings of Glinka-Balakirev’s “The Lark,” a set of beautiful variations). Quite naturally, most etymologists tried to find reference to morning or sound in the Germanic word. As early as 1846, Wilhelm Wackernagel, a famous philologist, believed that the old form consisted of lais- “furrow” and “waker”; the lark, he said, alerted the plowman that morning arrived and work should begin. Lais- would have been a cognate of Latin lira “furrow” (long i) and Engl. last (literally, “track”), as in cobbler’s last. This etymology was mentioned in a few old dictionaries and rejected, but it has found an enthusiastic modern supporter. The only non-controversial part of the reconstructed form laiwaza-k-on is -k-, a common suffix in animal and bird names. The part -aza- remains obscure; it has been called another suffix, but its meaning has not been discovered. I will skip several fanciful suggestions in which the poor lark lost a good deal of its plumage, and mention only one, because it belongs to an excellent scholar. In Sanskrit, the root lu- enters into many words meaning “cut.” Therefore, it has been proposed that the lark got its name from the habit of pecking at grains — an uninviting idea.

Two features of the lark are especially noticeable to humans: it is an early bird (whence its association with daybreak), and its songs (trills) are loud and melodious (after reading this post, listen to the recordings of Glinka-Balakirev’s “The Lark,” a set of beautiful variations). Quite naturally, most etymologists tried to find reference to morning or sound in the Germanic word. As early as 1846, Wilhelm Wackernagel, a famous philologist, believed that the old form consisted of lais- “furrow” and “waker”; the lark, he said, alerted the plowman that morning arrived and work should begin. Lais- would have been a cognate of Latin lira “furrow” (long i) and Engl. last (literally, “track”), as in cobbler’s last. This etymology was mentioned in a few old dictionaries and rejected, but it has found an enthusiastic modern supporter. The only non-controversial part of the reconstructed form laiwaza-k-on is -k-, a common suffix in animal and bird names. The part -aza- remains obscure; it has been called another suffix, but its meaning has not been discovered. I will skip several fanciful suggestions in which the poor lark lost a good deal of its plumage, and mention only one, because it belongs to an excellent scholar. In Sanskrit, the root lu- enters into many words meaning “cut.” Therefore, it has been proposed that the lark got its name from the habit of pecking at grains — an uninviting idea.

I can now come to the point. In lai- most researchers recognize a sound imitative complex. Last week, while discussing lollygag, I touched on the complex lal- ~ lol- ~ lul- ~ lil-. Among other things, it often refers to sound. Here we find such different words as Russian lai “barking,” Engl. lullaby, Engl. ululate “howl” (from French, from Latin), Engl. hoopla (from French), and a host of others. It matters little whether the lark’s call resembles la-la-la; in this situation, anything goes. Most dictionaries, unless they say “origin unknown (uncertain),” state that, although the etymology of lark is debatable, the word is onomatopoeic. Some authors add certainly and undoubtedly to their statements. Perhaps lark is indeed an onomatopoeia (la certainly and undoubtedly suggests sound imitation), but the problem of its ultimate origin remains.

The Latin for lark is alauda, and the Romans knew that their word was Gaulish (Celtic). Alauda and laiwazakon do not look like perfect congeners, but they are close enough to invite speculation about their affinity. The Latin noun (speciously) contains the root of laudare “praise” (compare Engl. laud, laudable, laudatory, and so forth), and this fact must have suggested to Minsheu the idea of the lark’s praising the Creator. The best nineteenth-century etymologists were puzzled by the similarity between læwerce and its kin and alauda. Jacob Grimm and Lorenz Diefenbach saw no serious arguments against uniting them, while their younger contemporaries showed some restraint. (Diefenbach’s name will mean nothing to non-specialists, but he was one of the greatest philologists of his generation.) Long ago — my reference takes me to 1887 — Moritz Heyne brought out volume six of the Grimms’ Dictionary and suggested that the hopelessly obscure word for “lark” had been borrowed from some other language. If we accept this hypothesis, the form in both Celtic and Germanic will emerge as an adaptation of the etymon we have no chance of finding. In recent years, the idea of the substrate has been much abused. Numerous words of unclear etymology have been given short shrift and assigned to some pre-Indo-European language of Europe. But the name of the lark does look like a loan from a lost source, for the etymology of Latin alauda is as impenetrable as that of laiwazakon.

Reference to the substrate leaves some phonetic details unexplained. Also, we will never know why the new inhabitants of Europe had no native name for such a widespread bird and how exactly the original word sounded. But perhaps we can risk the conclusion that lark is neither a Celtic nor a Germanic word (so that it cannot be represented as a compound made up of two Germanic roots) and that it probably contains an onomatopoeic element. This is a familiar denouement: the sought-for answer escapes us, but we seem to be closer to the truth than we were at the outset of our journey.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

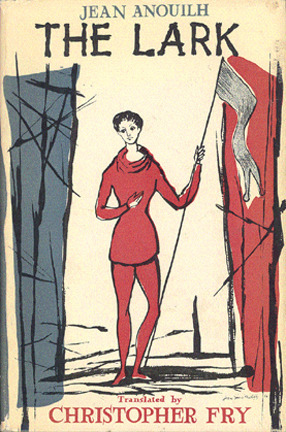

Image credit: Book cover. Jean Anouilh. The Lark. Christopher Fry, translator. New York: Oxford University Press, 1956. via Bryn Mawr.

The post Oh, what lark! appeared first on OUPblog.

Mars: A lexicographer’s perspective

The planet Mars might initially seem an odd choice for Place of the Year. It has hardly any atmosphere and is more or less geologically inactive, meaning that it has remained essentially unchanged for millions of years. 2012 isn’t much different from one million BC as far as Mars is concerned.

However, here on Earth, 2012 has been a notable year for the red planet. Although no human has (yet?) visited Mars, our robot representatives have, and for the last year or so the Curiosity rover has been beaming back intimate photographs of the planet (and itself). (It’s also been narrating its adventures on Twitter.) As a result of this, Mars has perhaps become less of an object and more of a place (one that can be explored on Google Maps, albeit without the Street View facility).

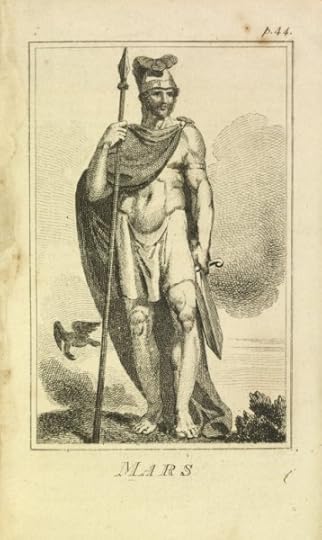

Our changing relationship with Mars over time is shown in the development of its related words. Although modern readers will probably associate the word ‘Mars’ most readily with the planet (or perhaps the chocolate bar, if your primary concerns are more earthbound), the planet itself takes its name from Mars, the Roman god of war.

Drawing of Mars from the 1810 text, “The pantheon: or Ancient history of the gods of Greece and Rome. Intended to facilitate the understanding of the classical authors, and of poets in general. For the use of schools, and young persons of both sexes” by Edward Baldwin, Esq. Image courtesy the New York Public Library.

From the name of this god we also get the word martial (relating to fighting or war), and the name of the month of March, which occurs at a time of a year at which many festivals in honour of Mars were held, probably because spring represented the beginning of the military campaign season.

Of course, nobody believes in the Roman gods anymore, so confusion between the planet and deity is limited. In the time of the Romans, the planet Mars was nothing more than a bright point in the sky (albeit one that took a curious wandering path in comparison to the fixed stars). But as observing technology improved over centuries, and Mars’s status as our nearest neighbour in the solar system became clear, speculation on its potential residents increased.

This is shown clearly in the history of the word martian. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the most common early usage of the word was as an adjective in the sense ‘of or relating to war’. (Although the very earliest use found, from Chaucer in c1395, is in a different sense to this — relating to the supposed astrological influence of the planet.)

But in the late 19th century, as observations of the surface of the planet increased in resolution, the idea of an present of formed intelligent civilization on Mars took hold, and another sense of martian came into use, denoting its (real or imagined) inhabitants. These were thought by some to be responsible for the ‘canals’ that they discerned on Mars’s surface (these later proved to be nothing more than an optical illusion). As well as (more or less) scientific speculation, Martians also became a mainstay of science fiction, the earth-invaders of H.G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds (1898) being probably the most famous example.

A century on, robotic explorers such as the Viking probes and the aforementioned Curiosity have shown Mars to be an inhospitable, arid place, unlikely to harbour any advanced alien societies. Instead, our best hope for the existence of any real Martians is in the form of microbes, evidence for which Curiosity may yet uncover.

If no such evidence of life is found, perhaps the real Martians will be future human settlers. Despite the success of Martian exploration using robots proxies, the idea of humans visiting or settling Mars is still a romantic and tempting one, despite the many difficulties this would involve. Just this year, it was reported that Elon Musk, one of the co-founders of PayPal, wishes to establish a colony of 80,000 people on the planet.

The Greek equivalent of the Roman god Mars is Ares; as such, the prefix areo- is sometimes used to form words relating to the planet. Perhaps, then, if travel to Mars becomes a reality, we’ll begin to talk about the brave areonauts making this tough and unforgiving journey.

Richard Holden is an editor of science words for the Oxford English Dictionary, and an online editor for Oxford Dictionaries.

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) is widely regarded as the accepted authority on the English language. It is an unsurpassed guide to the meaning, history, and pronunciation of 600,000 words — past and present — from across the English-speaking world. Most UK public libraries offer free access to OED Online from your home computer using just your library card number. If you are in the US, why not give the gift of language to a loved-one this holiday season? We’re offering a 20% discount on all new gift subscriptions to the OED to all customers residing in the Americas.

Oxford University Press’ annual Place of the Year, celebrating geographically interesting and inspiring places, coincides with its publication of Atlas of the World — the only atlas published annually — now in its 19th Edition. The Nineteenth Edition includes new census information, dozens of city maps, gorgeous satellite images of Earth, and a geographical glossary, once again offering exceptional value at a reasonable price. Read previous blog posts in our Place of the Year series.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only lexicography and language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Mars: A lexicographer’s perspective appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers