Oxford University Press's Blog, page 995

December 19, 2012

Why don’t ‘gain’ and ‘again’ rhyme?

This is a story of again; gain will be added as an afterthought. Throughout the first half of the twentieth century, dictionaries informed their users that again is pronounced with a diphthong, that is, with the same vowel as in the name of the letter A. (I am adding this explanation, because native speakers of English with no knowledge of phonetics seldom realize that the vowel in day, take, main consists of two parts: the nucleus and a glide; the formulation that, for example, a in bait is the “long counterpart of short a” in bat makes matters even worse.) Some people still rhyme again with fain, feign, fane. However, most rhyme it with Ben, den, ten; all the recent British and American dictionaries agree on this point.

The history of the adverb again is surprisingly checkered. In Modern English, the use of the digraphs ai, ay, and ei for short e is, as undergraduate students like to put it, not “very unique”: compare said, says, and heifer. But that does not make the puzzle easier, because says and said stand out as abnormal even in English, in which one can sometimes feel uncertain of how to spell the shortest words. Clearly, the spelling, irrational from today’s point of view, goes back to the pronunciation of old, but tracing the fortunes of each freak is no easy matter. This holds especially for heifer, but again too poses many difficulties.

Only the origin of again is clear. Among its cognates we find German entgegen “opposite” and Old Icelandic í gegn “against.” In the English word, the prefix a- goes back to the preposition on. Old Engl. ongean meant “in the opposite direction” and “back,” not “once more.” The oldest sense of -gain has been preserved in gainsay, literally “speak against.” The Germanic root of -gean and -gegn must have been gag-; its meaning need not occupy our attention, The vowel ea in ongean was long, which means that it consisted of two halves, each of which could be stressed, depending on the word’s place in the sentence, intonation, and emphasis. There was a time when in words of such structure stress shifted from e to a, though it is not clear whether the attested modern dialectal form agan owes its vowel to eá, from éa.

As far back as in Old English, the letter given here as g in ongean designated the sound we now hear in yes, you, and yonder. The interplay of g and y is common in the West Germanic languages. Those who have been exposed to the Berlin dialect know that, for instance, Gegend “area” sounds like yeyend there. In Middle High German, legt “lays” and trägt “carries” were spelled leit and treit. Old Engl. g- also changed to y- before i- and e-, and the modern forms yield and yearn bear witness to that change (their German cognates begin with g-: gelten and begehren). There would have been many more English words like those two but for the Viking raids. In the language of the Scandinavians, g remained “hard,” and that is why Modern Engl. get has not merged in pronunciation with yet. Also, give is a phonetic borrowing from the north, whether directly from the invading Danes or from the northern English dialects in which g- withstood “softening” to y-.

In Middle English, the most common form of again was ayen, still with a long vowel. To an unschooled observer the phonetic history of every well-documented language looks like an endless exercise in futility, a conspiracy invented for obfuscating beginning students. Long vowels become short and some time later undergo secondary lengthening, only to lose the hard-gained length a century or two later. Monophthongs turn into diphthongs, while diphthongs become monophthongs and occupy the slots vacated by their former neighbors. Wouldn’t it have been more natural for them to stay put and avoid playing lobster quadrille? Language is a self-regulating mechanism, and many changes only look erratic, but others are accounted for by the fact that sounds, like people, succumb to contradictory rules: from one point of view it may be expedient for a vowel to lengthen, but from another it would be better if it remained short or became long and then returned to its initial state. Phonetic system is like a modern democracy, which faces chaos and in trying to overcome it produces even greater chaos. There is no end to this process. In the history of again we observe how the original diphthong became a long monophthong, shortened, lengthened, and diphthongized. The coexistence of two modern pronunciations of again reflects those changes. Says and said exhibit partly the same picture, but only the short variants have survived.

AYENBITE OF INWYT

Somewhat unexpectedly, again is not pronounced ayen. In the fourteenth century, the Kentish English for “pricks (or rather “bite”) of conscience” was ayenbite of inwyt, as we know from the title of moralizing prose written in 1340 (compare backbiting). Ayen-bite is a morpheme by morpheme translation of Old French re-mors “remorse,” literally “biting with ever-increasing ‘mordancy’.” But by the seventeenth century the forms with ag- superseded those with ay-. As usual in such cases, suspicion falls on northern English or Scandinavian speakers. The reason why in this word the southern and central consonant gave way to northern g- has never been explained.Against surfaced as an adverb: Middle Engl. ageines is agein followed by an adverbial suffix. Its final -t is, to use a scholarly term, excrescent. This “parasitic” sound has also made its way after s into amidst, whilst, amongst, and a few others. A well-known vulgarism is acrossed. A similar change affected Old Engl. betweohs ~ betwyx ~ betwux: betwix became betwixt(e), and the idiom betwixt and between is still alive.

In distinction from again, gain (noun and verb) has an easily recoverable past. It is a borrowing of Old French gain (masculine; feminine gagne); the verb was gaigner (Modern French gagner). But the ancient word came to Romance from the Germanic verb for “hunt” and acquired the senses “cultivate land” and “earn.” It follows that gain in gainsay, in which again appears without its old prefix, and gain, as in gainful occupation, are distinct words, and only chance turned them into homophones and allowed them to meet in Modern English. Such is the story of gain1 and gain2. It is more complicated than what one could expect from a blog posted in late December, but nothing venture, nothing win, as the British say, or nothing ventured, nothing gained, as they say in America.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: King David does repentance

Nurturing a spirit of caring and generosity in children

At this holiday season, I would like to offer a few thoughts on how we can help nurture in our children a spirit of generosity and concern for others. I cannot write this post, however, without first expressing my deepest condolences to the families of Newtown, Connecticut, for their unimaginable and unbearable loss.

Much of the year, parents are understandably concerned with their children’s achievement. We focus our daily attention on helping children develop the skills they will need to succeed in a competitive world.

Most parents, however, want more for their children than individual achievement. We also want them to be “good kids” — children who act with kindness and generosity toward their families, their friends, and their communities. These are universal values, shared by parents who are secular and religious, liberal and conservative.

How can we best accomplish these goals? How can we nurture a child’s feelings of empathy and concern for others, of appreciation and gratitude, and a desire for giving, not just getting.

Caring and Responsibility

Several years ago, psychologists Nancy Eisenberg and Paul Mussen presented a comprehensive review of research on the development of pro-social behavior (caring, sharing, and helping) in children. They concluded that pro-social behavior begins with a child’s empathy (her awareness of the feelings of others) and is then strengthened when children observe the caring behavior of admired adults and older children.

Several years ago, psychologists Nancy Eisenberg and Paul Mussen presented a comprehensive review of research on the development of pro-social behavior (caring, sharing, and helping) in children. They concluded that pro-social behavior begins with a child’s empathy (her awareness of the feelings of others) and is then strengthened when children observe the caring behavior of admired adults and older children.

For young boys, a warm relationship with their father may be especially important. In one study, preschool boys who were generous toward other children portrayed their fathers as “nurturant and warm, as well as generous, sympathetic, and compassionate, whereas boys low in generosity seldom perceived their fathers in these ways.”

Eisenberg and Mussen also found that, across cultures, children who are given family responsibilities, including household chores and teaching younger children, show more helpful and supportive behavior toward their families and their peers.

In a more recent series of studies, psychologist Ross Thompson and his colleagues found that children’s moral understanding and pro-social behavior were also strengthened by a mother’s use of emotion language in conversation with her child. Mothers of children who were high in conscience used what Thompson labelled an “elaborative” conversational style and made frequent references to other people’s feelings.

Ideals and Idealism

In thinking about children’s moral development, we also need to remember the intangibles. Our children look up to us. They look up to us even when they are angry and defiant, or when they are defensive or withdrawn, and even when, as adolescents (or before), they challenge our ideas and rebel against our rules.

Because they look up to us, they want to be, and to become, like us. We can observe this, every day, in the admiring statements of young children, when first grade boys and girls tell their teacher, “I want to be fireman, like my daddy” or “I want to be a doctor and help people, like my mom.” Recall the looks on the faces of Scout and Jem when Atticus talks with them, or when he delivers his summation to the jury in To Kill a Mockingbird.

A child’s admiration of her parents is an important moral influence throughout childhood — a source of conscience, ideals, and long-term goals. When a child looks up to us — and in return, feels our genuine interest, warmth, and pride — we have strengthened an important pathway of healthy development, a pathway that leads toward commitment to ideals and a sense of purpose in life.

We also support our children’s idealism when we talk with them about people we admire, people who have inspired us and who we hope will inspire them. We need to let them know that there is so much good work to be done in the world, work that they will be able to do and can do, even now. And we should help them appreciate what others do for us. We should talk with them about heroes who may not be famous, heroes of everyday life: the people who build our cities, protect our safety, and save our lives.

Doing for Others

A growing body of scientific research now supports an important conclusion: Doing good for others is also good for us. Most of this research has been conducted with late adolescents and adults. My personal experience suggests that doing for others is also good for children.

In a recent review, psychologist Jane Piliavin concluded that community service (helping others as part of an institutional framework) leads to improved self-esteem, less frequent depression, better immune system functioning, even a longer life.

Piliavin found significant benefits when older elementary school students read to kindergartners or first graders. Good effects, including lower dropout rates, were also reported when middle school students were randomly assigned to tutor younger children, as little as 1 hour a week. An evaluation of student volunteering that involved 237 different locations and almost 4,000 students concluded that volunteering “led to increased intrinsic work values, the perceived importance of a career, and the importance of community involvement.”

I therefore now recommend that parents find some way, especially as a family, to make doing for others a regular, not just occasional, part of their children’s lives. Children learn from this work that they have something to offer and they experience the appreciation of others. They learn how good it feels, to themselves and to others, to do good work.

Kenneth Barish is the author of Pride and Joy: A Guide to Understanding Your Child’s Emotions and Solving Family Problems and Clinical Associate Professor of Psychology at Weill Medical College, Cornell University. He is also on the faculty of the Westchester Center for the Study of Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy and the William Alanson White Institute Child and Adolescent Psychotherapy Training Program. Read his previous blog posts on parenting.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Big sister sharing her books and showing little brother pictures. Photo by JLBarranco, iStockphoto.

The post Nurturing a spirit of caring and generosity in children appeared first on OUPblog.

Ulster since 1600: politics, economy, and society

For many people the terms Ulster, Northern Ireland, and ‘the North’ conjure up images of communal conflict, sectarianism, and peace processes of indefinite duration. More than 3,500 people were killed in the national, communal and sectarian conflict that engulfed Northern Ireland between 1969 and Easter 1998 when the Good Friday Agreement was signed. Tens of thousands were injured or maimed, while sporadic acts of political violence persist to this day.

The near-present is a powerful influence on how we view the past. Yet, in many respects, these blood-spattered years serve to distort our understanding of the lived experience of people in Ulster from 1700 onwards. True enough, this was an ethnically-divided society, but one characterised by complexities, ambiguities, contrariness and the unexpected. Above all, it is necessary to appreciate that violence was not the dominant motif in most time periods in recent centuries.

In 1600, Ulster was a thinly populated, economically backward region. By 1900, without the benefit of local coal or iron, the Belfast region had emerged as a significant industrial and commercial centre in western Europe. This social and economic dynamism was based, first, on linen textiles and later on shipbuilding and engineering. Elsewhere in Ulster, more traditional but vigorous small-farming enterprises predominated.

The story of Ulster since 1600 is one of dramatic transformation, in which immigrant entrepreneurs and workers played a vital role. Moreover, in terms of economic geography and social networks, east Ulster was well placed to benefit from the English and Scottish industrial revolutions. In fact, the north east of Ireland was the only part of the island of Ireland to experience modern industrialisation and urbanisation on a major scale. By the time of political independence in ‘southern’ Ireland, Belfast stood out as Ireland’s only industrial city.

But here is one of the many paradoxes. Despite these modernising tendencies, Belfast and the lesser towns of Ulster incubated and perpetuated forms of politico-religious conflict that have outlived similar tendencies that were once characteristic of many parts of western Europe.

There are other paradoxes. The economic trajectory of Ulster in the eighteenth century, though marred by periodic crises, was generally upwards. Yet the province of Ulster experienced higher levels of emigration, particularly to North America, than any of the other Irish provinces. These emigrants, Presbyterians in the main, went on to forge other lives in the New World. A disproportionate number were involved on the insurgents’ side in the American war of independence. At home, a minority of Presbyterians were active in the radical United Irishmen, seeking reform of the Anglican and landlord-dominated Irish political system.

Presbyterian radicalism took a new turn in the following century, focusing on reform of the landlord and tenant system and local government, but within the framework of the Union of Britain and Ireland. The industrial success of east Ulster in turn served to solidify support for the Union, among Protestant workers as well as captains of industry, aided by a resurgent Orange Order. The comparative underdevelopment of the south and west of Ireland provided ideological justification for emerging Irish nationalist and Catholic opposition to the Union. It is significant, though, that members of the Catholic working class in Belfast, Derry and Newry were not swayed by economic arguments. In conjunction with their co-religionists, they sought Home Rule and later political independence for all of Ireland.

The partition of the island in 1920-21, with six of the original nine Ulster counties forming the new statelet of Northern Ireland, was a major source of grievance to Irish nationalists, North and South. Yet much of social and cultural life proceeded as before – arguably the continuities were as important as the discontinuities – though the heat and invective of political partisanship was sometimes imported into activities as diverse as sport, schooling and language revival.

The formative phase in the making of modern Ulster was undoubtedly during the Plantation of Ulster. But maybe Ulster was a place apart, even before then, as Estyn Evans has suggested? Indeed has the distinctiveness of Ulster in recent centuries been overstated, as some others have suggested? These, and many other questions, find at least partial answers within the pages of Ulster Since 1600.

Philip Ollerenshaw is Reader in History at the University of the West of England, Bristol. He is the author or editor of several books on economic, financial, and urban history, including Ulster since 1600: Politics, Economy, and Society (co-edited with Liam Kennedy; OUP, 2012) .

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Ulster since 1600: politics, economy, and society appeared first on OUPblog.

December 18, 2012

Reflections on the shooting at the Sandy Hook Elementary School

The mass shooting in Newtown, Connecticut is a tragic event that is particularly painful as it comes at a time when people across the world are trying to focus on the upcoming holidays as the season of peace bringing good tidings of great joy.

Three factors about the Newtown school shooting are noteworthy. First, it was a mass murder. Second, it appears to have been precipitated by the killing of a parent (parricide). Third, it was committed by a 20-year old man. All of these factors are relevant in making sense of what appears to be inexplicable violence.

What drives a person to take an assault rifle into an elementary school and open fire on very young children and the teachers, some of whom died protecting them? Individuals in these cases are typically suicidally depressed, alienated, and isolated. They have often suffered a series of losses and are filled with a sense of rage. All too frequently they see themselves as having been wronged and want to play out their pain on a stage. The fact that mass shootings are routinely covered in depth by the media is not lost on them. They are typically aware that their name will go down in history for their destructive acts. Their murderous rampage is an act of power by an individual who feels powerless. Unable to make an impact on society in a positive way, the killer knows that he can impact the world through an act of death and destruction.

The fact that the first victim was reportedly the victim’s mother is significant. The first victims in other adolescent school shootings have also involved parents in some cases. My research and clinical practice has indicated that there are four types of parricide offenders.

The first type is the severely abused parricide offender who kills out of desperation or terror; his or her motive is to stop the abuse. These individuals are often diagnosed as suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder or depression.

The second type is the severely mentally ill parricide offender who kills because of an underlying serious mental illness. These individuals typically have a longstanding history of severe mental illness, often along the schizophrenia spectrum disorder or might be diagnosed as having depression or bi-polar disorder with psychotic features.

The third type is the dangerously antisocial parricide offender who kills his or her parent to serve a selfish, instrumental reason. Reasons include killing to get their parents’ money, to date the boy or girl of their choice, and freedom to do what they want. These individuals are often diagnosed as having conduct disorder if under age 18 and antisocial personality disorder if over age 18. Some meet the diagnostic criteria of psychopathy. Psychopaths have interpersonal and affective deficits in additional to antisocial and other behavioral problems. They lack a connection to others and do not feel empathy. They do not feel guilty for their wrongdoing because they do not have a conscience.

The fourth type is a parricide offender who appears to have a great deal of suppressed anger. If the anger erupts to a boiling point, the offspring may kill in an explosive rage often fueled by alcohol and/or drugs.

Interestingly, most parents are slain by their offspring in single victim-single offender incidents. Multiple victims incidents are rare. In an analysis of FBI data on thousands of parricide cases reported over a 32 year period, I found that on the average there were only 12 cases per year when a mother was killed along with other victims by a biological child. In more than 85% of these cases, the matricide offender was a son.

The actual number of victims involved in multiple victim parricide situations was small, usually two or three. Murders of the magnitude as seen in Newtown, CT that involved a parent as a first victim are exceedingly rare.

Assessment of the dynamics involved in the killing of parents is also important in terms of prognosis and risk assessment. The first victims of some serial murderers were family members, including parents. Serial murderers are defined as individuals who kill three or more victims in separate incidents with a cooling off period between them. If the parricide offender intended to kill his parent and derived satisfaction from doing so, he represents a great risk to society. (This type of killer is known as the Nihilistic Killer.)

The gunman’s age (in Newtown’s case, he was 20 years old) is also an important factor in understanding how an individual could engage in such horrific violence. Research has established that the brain is not fully developed until an individual reaches the age of 23 to 25 years old. The last area of the brain to develop is the pre-frontal cortex. This area of the brain is associated with thinking, judgment, and decision making. A 20-year-old man filled with rage would have great difficulty stopping, thinking, deliberating, and altering his course of action during his violent rampage. He is likely to be operating from the limbic system, the part of the brain associated with feelings. Adam Lanza was likely driven by raw feeling and out of control when he sprayed little children with rounds of gunfire. Simply put, it would be very difficult for him to put the brakes on and desist from his violent behavior.

Events like the shooting in Newtown leave society once again asking what can be done to stop the tide of senseless violence. Clearly Adam Lanza and other mass killers have been able to kill dozens of people in a matter of a few moments because of high powered weaponry. It is time to ask whether our nation can continue to allow assault weapons appropriate for our military to be easily available to citizens in our society. It is time for us to ask what can be done to increase access to mental health services to those who desperately need them. My prediction is, when the facts are more clearly known, risk factors will be identified in the case of Adam Lanza and missed opportunities to intervene to help Adam will be uncovered, contributing to the profound sadness that we are experiencing in the United States and across the world.

Kathleen M. Heide, Ph.D., is Professor of Criminology at the University of South Florida. Her lastest book, Understanding Parricide: When Sons and Daughters Kill Parents, was published in December 2012 by Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Reflections on the shooting at the Sandy Hook Elementary School appeared first on OUPblog.

Some warning behaviors for targeted violence

As the debate concerning public and social policy surrounding gun control intensifies, I would like to offer some comments on the identification of individuals who concern us as potential perpetrators of planned killing(s). These thoughts are from the trenches of threat assessment, and don’t address or offer opinions concerning the larger policy issues we face as a country regarding firearms and public mental health care — one of which is emotionally charged and the other sorely neglected.

The usual demographic characteristics such as a young male, loner, psychiatrically impaired, bullied, and angry don’t work as markers of risk, simply because there are hundreds of thousands of individuals in the USA, and the world, who match these demographics and pose no risk at all. The disturbing fact is that targeted violent events, such as the mass murder in Newtown, cannot be predicted because they are too rare. If we attempt to do this, we err on the side of labeling thousands of individuals as potential perpetrators when they are not a risk at all. So where do we turn?

For the past several years we have been working on identifying warning behaviors (acute and dynamic patterns of risk), which may signal an impending act of targeted violence, including mass murder. These patterns create concern in observers, and warrant a reasonable response to mitigate such risk, whether that involves increased community and educational attention, mental health intervention, or law enforcement interdiction. Anyone can evidence these warning behaviors:

Pathway warning behavior: any behavior that is part of research, planning, preparation, or implementation of an attack.

Fixation warning behavior: any behavior that indicates an increasingly pathological preoccupation with a person or a cause. There is a noticeable increase in perseveration; strident opinion; negative statements about the target(s); increasing anxiety and/or fear in the target; and an angry emotional undertone. It is accompanied by social or occupational deterioration.

Identification warning behavior: any behavior that indicates a psychological desire to be a “pseudocommando” or have a “warrior mentality”, closely associate with weapons or other military paraphernalia, identify with previous attackers or assassins, or identify oneself as an agent to advance a particular cause or belief system.

Novel aggression warning behavior: an act of violence which appears unrelated to any pathway warning behavior which is committed for the first time, often to test the ability of the individual to actually do a violent act.

Energy burst warning behavior: an increase in the frequency or variety of any noted activities related to the target, even if the activities themselves are relatively innocuous, often in the hours or days before the attack.

Leakage warning behavior: the communication to a third party of an intent to do harm to a target through an attack.

Last resort warning behavior: increasing desperation or distress through declaration in word of deed; there is no other choice but violence, and the consequences are justified.

Directly communicated threat warning behavior: the communication of a direct threat to the target or law enforcement beforehand.

If we observe these warning behaviors in others, we should be concerned. If we see something, we should say something. We don’t know if these warning behaviors predict targeted violence, yet these accelerating patterns have been found in a number of small samples of subjects in Germany and the US that have committed school shootings, mass murders, attacks and assassinations of public figures, and acts of terrorism. We are getting some tantalizing results: in comparing a small sample of school shooters and school threateners in Germany, our research group (with Dr. Jens Hoffmann) found that the school shooters were much more likely to exhibit pathway, fixation, identification, novel aggression, and last resort warning behaviors when compared to the school threateners who had no intention to attack. Although the samples were small, the effect sizes were large in a statistical sense.

The paradox in all this work — targeted violence threat assessment — is that we will never know which of the individuals of concern would have carried out an act of violence if there had been no intervention.

J. Reid Meloy, Ph.D. is Clinical Professor of Psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego, and President of Forensis, Inc., a nonprofit dedicated to forensic psychiatric and psychological research. He co-edited Stalking, Threatening, and Attacking Public Figures (OUP, 2008) with Lorraine Sheridan and Jens Hoffmann, and is currently co-editing another volume entitled International Handbook of Threat Assessment, which is scheduled to publish in 2013. Learn about his latest news by following Forensis on Twitter at @ForensisInc. The scientific basis of this blog article is available in Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 30:256-279, 2012.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Some warning behaviors for targeted violence appeared first on OUPblog.

The Naming of Hobbits

It will be interesting to see how much of J.R.R. Tolkien’s several invented languages will appear in Peter Jackson’s The Hobbit. In a letter to his American publisher, dated 30 June 1955, Tolkien suspected there were limits to how much invented language readers would ‘stomach’ — to use his term. There are certainly limits to how much can be included in a film. American audiences, anyway, are subtitle averse.

Of Tolkien’s invented languages, Elvish receives most attention, not unreasonably, since it is illustrated most often in Tolkien’s works and most fully articulated in his manuscripts. Other languages are essential to The Lord of the Rings, however. When Gandalf reads out the delicately curved Elvish script on the One Ring in the rough-hewn Black Tongue of Mordor it represents so incongruously, Tolkien proves that some language — just the sound of it — can petrify us as surely as any Ringwraith. Tolkien’s languages aren’t suitable only for poetry or gnomic verses on rings. They also include the element of language most familiar to speakers speaking to one another every day, namely, names.

Tolkien as Philologist

When Tolkien came up with what sounded to him like a name, he would play with it a bit, experiment with its sound structure, and eventually a system of linguistically related names would emerge. Thus a family was invented, a family with relationships to other families in a mythical place, ready to take part in stories. As Tolkien explained in the letter already mentioned, “The ‘stories’ were made rather to provide a world for the languages than the reverse. To me a name comes first and the story follows.” And in his lecture on creating languages, ‘A Secret Vice’ (1931), he wrote “the making of language and mythology are related functions” and an invented language, at least one developed at length, will inevitably “breed a mythology.”

A slip written by J.R.R. Tolkien on the etymology of “walrus” during his years working for the Oxford English Dictionary. Image courtesy the Oxford University Press Archives.

Tolkien was always a philologist, whether in scholarship or fiction. He treated his fictional languages as though they were real, as though he were discovering rather than inventing them. In his scholarship, reconstruction of the sound system or grammar of languages like Old English and Old Norse was routine. For instance, he wrote ‘Appendix I: The Name “Nodens”’, in the Report on the Excavation of the Prehistoric, Roman, and Post-Roman Sites in Lydney Park, Gloucestershire, published by the Research Committee of the Society of Antiquaries of London (1932). So, it isn’t in every library, but it has been helpfully reprinted in Volume 4 of the annual journal Tolkien Studies (2007). In it, you will find passages like this one: “Although it is perhaps vain to try and disentangle from the things told of Nuada any of the features of Nodens of the Silures in Gloucestershire, it is at least highly probably that the two were originally the same. This is borne out by the isolation of the name in Keltic [sic] material, the importance of Nuada (and of Nodens), and not least by the exact phonological equation of Nōdont- with later Nuadat.” This reads very much like a passage from one or another appendix to The Lord of the Rings, and if you read it without knowing it deals with a matter of linguistic and historical fact, you might well think it was fiction.

How to Name a Baggins

Many names in Tolkien’s fiction are not invented, or, at least, not invented by him. Nearly all of the names of dwarfs in The Hobbit can be found in Dvergatal or ‘Tally of the Dwarfs’ in the Old Norse poetic Edda, as can the Old Norse precursors of Gandalf and Thorin’s nickname, Oakenshield. Hobbit names are an interesting blend of borrowed and invented items. For instance, a few males of the Baggins family of Hobbits sometimes bear real — though indisputably outmoded — personal names, such as Drogo (name popular among the French nobility c1000 CE, but since, not so much), Dudo (name of a tenth-century Norman historian and ecclesiast), and Otho (name of a Roman emperor). Other masculine names are converted from surnames or words found in natural languages, such as Balbo, Bingo, Fosco, Largo, Longo, Minto, Polo, and Ponto. But still others appear to be well and truly invented by Tolkien, such as Bilbo, Bungo, and Frodo. Perhaps they were invented to sound and look like the borrowed and converted names, but more likely those were found to fit patterns implied by the invented ones.

The 1937 Allen & Unwin hardback edition cover designed by Tolkien.

Many female Bagginses were given English flower names, such as Daisy, Lily, Myrtle, Pansy, Peony, and Poppy. Others had personal names common in English and other natural languages, for instance, Angelica, Dora, Linda, and Rosa. And a few bore personal names converted from surnames, like Belba, or historical but unfamiliar personal names, like Prisca (name of a Roman empress). The repurposing of such names and words as names of Hobbits may be inventive yet not count as an invention. Yet the invention is not of the names themselves — not most of them, anyway — but of linguistic relations among the names and social relations, embedded in the linguistics, among those to whom they belong.

The names have no actual relation to one another. They are borrowed from Italian and Scots and Norman French, or in those few cases made up. Tolkien brought them into relation by means of their sound shapes: the masculine names, whatever the source, and for whatever genuine etymological reason, are all two syllables and end in -o, which is proposed as a mark of the masculine name in the naming practices of Bagginses. For female Bagginses, the flower names are a fashion that obscures the way gender is marked in Baggins names: Belba, Dora, Linda, Prisca, and Rosa are marked with the contrasting feminine -a. Among all of the flower names, the -a names suggest a diminishing but tenacious historical tendency. But all language changes, as do naming practices, and any reconstruction of personal names in a historical language must account for remnant forms, anomalies, and generational trends.

There and Back Again

Other Hobbit clans have different types of names from those of the Bagginses. Brandybuck names have a distinctly Celtic shape, given the profuse -doc suffix: Gormadoc, Marmadoc, Saradoc, and, of course, Meriadoc. The Tooks prefer names from medieval romance and beast epic: Adelard, Ferumbras, Flambard, Fortinbras (rather than Armstrong, which has a quite different shape), Isengrim, and Sigismund, for instance. The Longfathers have names constructed from Anglo-Saxon elements: Hamfast and Samwise, in which -wise may mean, as it sometimes does in Anglo-Saxon, ‘sprout, stalk’. Over the generations, clan marries into clan, and the names mingle and develop new patterns: the names are the genealogical architecture of a culture.

Through alliances and friendships, Hobbit culture reticulates into the wider web of cultural relationships across Middle Earth and deep into the mythology of which the story of Middle Earth is only a part. The linguistic bases for cultural relationship and contrast are woven tightly and everywhere into the fabric of Tolkien’s fiction. In the middle of the mythological pattern, Tolkien has pricked in the -o and the -a, suffixes that say something about who the Bagginses are, or who they think they are, something that allows one Baggins to find the Ring and another to destroy it, just in time.

Michael Adams teaches English language and literature at Indiana University. In addition to editing and contributing to numerous linguistic journals, he is the author of Slang: The People’s Poetry and Slayer Slang: A Buffy the Vampire Slayer Lexicon, and he is the editor of From Elvish to Klingon: Exploring Invented Languages.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only lexicography and language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post appeared first on OUPblog.

Christmas dinner with the Cratchits

Following yesterday’s recipe for roast goose by Mrs Beeton, here’s that classic Christmas dinner portrayed by Charles Dickens in the famous scene from A Christmas Carol. Here Ebeneezer Scrooge watches with the Ghost of Christmas Present as the Cratchit family sits down to roast goose and Christmas pudding.

‘And how did little Tim behave?’ asked Mrs Cratchit, when she had rallied Bob on his credulity, and Bob had hugged his daughter to his heart’s content.

‘As good as gold,’ said Bob, ‘and better. Somehow he gets thoughtful, sitting by himself so much, and thinks the strangest things you ever heard. He told me, coming home, that he hoped the people saw him in the church, because he was a cripple, and it might be pleasant to them to remember upon Christmas Day, who made lame beggars walk, and blind men see.’

Bob’s voice was tremulous when he told them this, and trembled more when he said that Tiny Tim was growing strong and hearty.

Bob’s voice was tremulous when he told them this, and trembled more when he said that Tiny Tim was growing strong and hearty.

His active little crutch was heard upon the floor, and back came Tiny Tim before another word was spoken, escorted by his brother and sister to his stool before the fire; and while Bob, turning up his cuffs — as if, poor fellow, they were capable of being made more shabby — compounded some hot mixture in a jug with gin and lemons, and stirred it round and round and put it on the hob to simmer; Master Peter, and the two ubiquitous young Cratchits went to fetch the goose, with which they soon returned in high procession.

Such a bustle ensued that you might have thought a goose the rarest of all birds; a feathered phenomenon, to which a black swan was a matter of course — and in truth it was something very like it in that house. Mrs Cratchit made the gravy (ready beforehand in a little saucepan) hissing hot; Master Peter mashed the potatoes with incredible vigour; Miss Belinda sweetened up the apple-sauce; Martha dusted the hot plates; Bob took Tiny Tim beside him in a tiny corner at the table; the two young Cratchits set chairs for everybody, not forgetting themselves, and mounting guard upon their posts, crammed spoons into their mouths, lest they should shriek for goose before their turn came to be helped. At last the dishes were set on, and grace was said. It was succeeded by a breathless pause, as Mrs Cratchit, looking slowly all along the carving knife, prepared to plunge it in the breast; but when she did, and when the long expected gush of stuffing issued forth, one murmur of delight arose all round the board and even Tiny Tim, excited by the two young Cratchits, beat on the table with the handle of his knife, and feebly cried Hurrah!

There never was such a goose. Bob said he didn’t believe there ever was such a goose cooked. Its tenderness and flavour, size and cheapness, were the themes of universal admiration. Eked out by apple-sauce and mashed potatoes, it was a sufficient dinner for the whole family; indeed, as Mrs Cratchit said with great delight (surveying one small atom of bone upon the dish), they hadn’t ate it all particular, were steeped in sage and onion to the eyebrows! But now, the plates being changed by Miss Belinda, Mrs Cratchit left the room alone — too nervous to bear witness — to take the pudding up and bring it in.

Suppose it should not be done enough! Suppose it should break in turning out! Suppose somebody should have got over the wall of the back-yard, and stolen it, while they were merry with the goose — and supposition at which the two young Cratchits became livid! All sorts of horrors were supposed.

Hallo! A great deal of steam! The pudding was out of the copper. A smell like a washing-day! That was the cloth. A smell like an eating-house and a pastrycook’s next door to each other, with a laundress’s next door to that! That was the pudding! In half a minute Mrs Cratchit entered — flushed by smiling proudly — with the pudding, like a speckled cannon-ball, so hard and firm, blazing in half of half-a-quartern of ignited brandy, and bedight with Christmas holly stuck into the top.

Oh, a wonderful pudding! Bob Cratchit said, and calmly too, that he regarded it as the greatest success achieved by Mrs Cratchit since their marriage. Mrs Cratchit said that now the weight was off her mind, she would confess she had her doubts about the quantity of flour. Everybody had something to say about it, but nobody said or thought it was at all a small pudding for a large family. It would have been flat heresy to do so. Any Cratchit would have blushed to hint at such a thing.

At last the dinner was all done, the cloth was cleared, the hearth swept, and the fire made up. The compound in the jug being tasted, and considered perfect, apples and oranges were put upon the table, and a shovel-full of chestnuts on the fire. Then all the Cratchit family drew round the hearth, in what Bob Cratchit called a circle, meaning half a one; and at Bob Cratchit’s elbow stood the family display of glass. Two tumblers, and a custard-cup without a handle.

These held the hot stuff from the jug, however, as well as golden goblets would have done; and Bob served it out with beaming looks, while the chestnuts on the fire sputtered and cracked noisily. Then Bob proposed:

‘A Merry Christmas to us all, my dears. God bless us!’ Which all the family re-echoed.

‘God bless us every one!’ said Tiny Tim, the last of all.

A Christmas Carol has gripped the public imagination since it was first published in 1843, and it is now as much a part of Christmas as mistletoe or plum pudding. The Oxford World’s Classics edition, edited by Robert Douglas-Fairhurst, reprints the story alongside Dickens’s four other Christmas Books: The Chimes, The Cricket on the Hearth, The Battle of Life, and The Haunted Man.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Reproduced from a c.1870s photographer frontispiece to Charles Dicken’s A Christmas Carol. By Frederick Barnard (1846-1896). Digital image from LIFE. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Christmas dinner with the Cratchits appeared first on OUPblog.

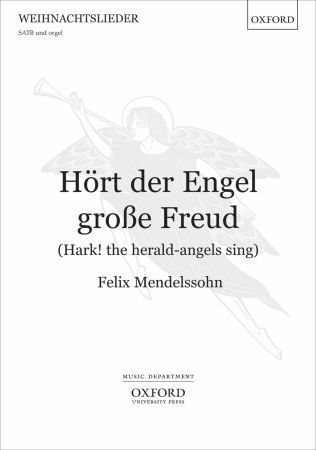

Top ten Christmas carols of 2012

Christmas is the busiest time of year for the Oxford University Press Music Hire Library. With everyone wanting to include festive music in their December concerts the three Library worker elves are kept scurrying around the mile-long stretch of music shelves from September to December, busily packing up orders in time for Christmas concert rehearsals.

Music Hire Library Team: They’ve gone crazy from all the Christmas preparation!

With the fight to be Christmas No 1 in the charts still on, we thought we’d compile our own greatest hits of Christmas 2012. So, now that the orders are all in, and parcels of carols are winging their way to choirs and orchestras around the globe, we’ve totted up the orders for our festive music. Here’s the top ten for 2012:

10. Good King Wenceslas; Reginald Jacques

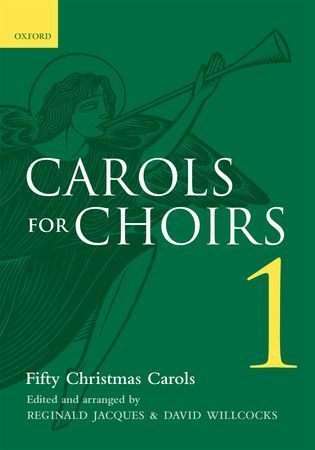

From Carols for Choirs 1

9. Shepherd’s Pipe Carol; John Rutter

8. We wish you a Merry Christmas; Arthur Warrell

From Carols for Choirs 1

7. On Christmas Night; Bob Chilcott

6. The Twelve Days of Christmas; John Rutter

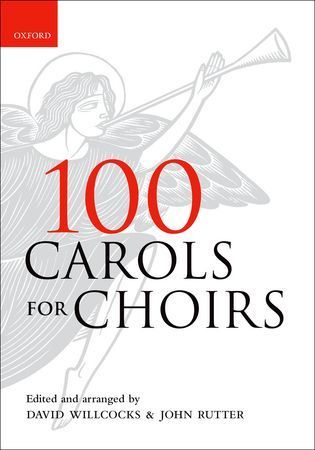

From Carols for Choirs 2 and 100 Carols for Choirs

Click here to view the embedded video.

5. Sans Day Carol; John Rutter

From Carols for Choirs 2 and 100 Carols for Choirs

4. Angels’ Carol; John Rutter

Click here to view the embedded video.

3. Jingle Bells; Sir David Willcocks

2. Hark! The Herald Angels sing; Mendelssohn

And….

1. O come, all ye Faithful; Sir David Willcocks

Click here to view the embedded video.

Iain Mackinlay is the Music Hire Manager at Oxford University Press. To find out more about these and other Christmas music published by OUP visit our website. Oxford Sheet Music is distributed in the US by Peters Edition.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: All images property of Oxford University Press. Do not reproduce without prior express written permisson.

The post Top ten Christmas carols of 2012 appeared first on OUPblog.

December 17, 2012

How to help your children cope with unexpected tragedy

Children look to their parents to help them understand the inexplicable. They look to their parents to assuage worries and fears. They depend on their parents to protect them. What can parents do to help their children cope with mass tragedy, such as occurred this week with the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut?

The first thing that parents can do is to calm themselves. Remember that your children will react to your fear and distress. It will be reassuring to them to see that you are calm and not afraid to discuss the event with them.

Next, parents can consider limiting their children’s exposure to media coverage and to adult discussions of the shooting. Young children may have particular difficulty understanding what they see on news stories and what they overhear from adult discussions. They may also have difficulty assessing their own level of safety.

It can be helpful for parents to check in with their children in order to learn about their thoughts and emotional reactions to the shooting. After carefully listening to their children, parents can then determine if it is necessary to correct distressing misunderstandings, answer questions, validate feelings of anger or sadness, and remind their children about how their family members and others, including police officers, help to keep them safe.

Most children will not be traumatized by their media exposure to the shooting, but they may have questions or concerns. Some children will be fearful about returning to school or have other signs of distress, but will adjust with the support and reassurances provided by parents and others. Children who are especially sensitive, those who have a tendency to worry, those with little emotional support, and those who have been previously traumatized, may be more vulnerable.

Trauma symptoms among children vary, but include talking about the event, distress when reminded of the trauma, nightmares, new separation anxiety or clinginess, new fears, sleep disturbance, physical symptoms (such as stomachaches), and more irritability or tantrums. Children may regress, that is, soothe or express themselves in ways they did when they were younger. For example, they might want to sleep with parents or they may wet the bed. Parents might notice an increase in behavioral problems or a decrease in school functioning. If these symptoms don’t improve in the coming weeks, such children may benefit from professional assistance.

Children are reassured by calm and supportive adults, by their normal routines, and by age-appropriate information when they have questions or misconceptions. For those children with ongoing signs of trauma, effective treatments are available. For additional information, parents can access information from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network website.

Brenda Bursch, PhD is a pediatric psychologist and Professor of Psychiatry & Biobehavioral Science, and Pediatrics at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. She is co-author of “How Many More Questions?” : Techniques for Clinical Interviews of Young Medically Ill Children.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post How to help your children cope with unexpected tragedy appeared first on OUPblog.

How many more children have to die?

Surely the time has finally come to put our heads together and focus on three seldom connected variables regarding mass murders in the United States: the lack of comprehensive psychiatric care for individuals with mental illness, poor public recognition of the red flags that an individual might harm others, and easy access to firearms.

How should we address the first problem? The fiscal problems this country has faced during the past decade, combined with skewed budget priorities, have lead to a significant reduction in public health care, in particular for mental illness. Insurance companies have limited the time providers have for mental health assessments, the duration and frequency of treatment, and the types of intervention they cover. These cutbacks have forced psychiatrists to do abbreviated and superficial psychiatric evaluations and to prescribe medications as stopgap treatment in lieu of more effective evidence-based therapies. Furthermore, the number of individuals without mental health coverage who also face unemployment, homelessness, or insufficient money to feed and clothe their families — all significant mental health stressors — is steadily rising.

How then can mental health professionals conduct the comprehensive, time consuming evaluations needed to determine if an individual might be dangerous towards others? Self-report questionnaires, another quick method professionals use to conduct psychiatric evaluations, are clearly not the answer. Few people with homicidal or suicidal thoughts acknowledge these “socially unacceptable” intentions or plans on paper. Expert clinical acumen is needed to carefully and sensitively help patients talk about these “taboo” topics and their triggers. A five-to-ten minute psychiatric appointment clearly doesn’t do the job!

The lack of comprehensive mental health care is most sorely evident for such conditions as schizophrenia, as well as psychosis associated with substance abuse, depression, bipolar disorder, neurological disorders, or medical illnesses. In these conditions individuals can be plagued by and act in response to hallucinations that include voices commanding them to kill or visions that incite their aggressive response. Delusions (rigid, pervasive, and unreasonable thoughts) that people threaten them can also cause an aggressive response. Mass murderers might act out their hallucinations and delusions, as in the attempted assassination of congresswoman Gabrielle Gifford and murder of five bystanders, and in the Columbine, Batman, and Virginia Tech massacres.

Lack of time often precludes pediatric professionals from seeing children without their parents and detecting early warning signs of homicidal or suicidal plans. Similarly, physicians might have time to talk to adolescents but not to their parents. As a result, they might miss hearing about red flags of possible aggression by the youth and/or his peers.

The Affordable Care Act (Obamacare) will provide health insurance for more people, but what about quality mental health care? Few mentally ill patients are able to fight for their sorely needed unmet mental health care needs. Due to the stigma of mental illness and the related financial and heavy emotional burden, their families seldom have the power and resources needed to lobby elected officials or use the Internet and other media to publicize their plight.

How can we recognize the red flags of a potential mass murderer? In addition to well-trained mental health professionals with expertise, clinical acumen, and sufficient time with their patients, there is a need to educate the public about severe mental illness. Parents, family members, teachers, community groups, and religious leaders all need instruction to recognize possible early signs of mental illness. This knowledge will help them understand the plight and suffering of individuals with severe mental illness. And, most importantly, this awareness can lead to early referral, treatment, and prevention of violence due to mental illness.

Prompt recognition and early treatment of these symptoms are essential because firearms are so easily obtained in the United States. To get a driver’s license, individuals complete a Driver’s Ed course, pass a knowledge test, take driving lessons, drive a car with an adult for a fixed period, and then take a driving test. The underlying assumption is that irresponsible driving can physically harm others, the driver, and property. For this reason, individuals with epilepsy who experienced a seizure within the past year are barred from driving. Shouldn’t the same principles apply to guns? Yet, individuals can obtain guns without prior psychiatric evaluations, and there are no laws and regulations to safeguard these weapons in homes to prevent children and individuals with severe mental illness from gaining access to them. Reports on accidents caused by children and suicide by adolescents with their parents’ guns are common. According to a Center for Disease Control study, 1.6 million homes have loaded and unlocked firearms (Okoro et al., 2005).

As a child psychiatrist and parent, I regard the Newtown horrific mass murder of elementary age children as a final wake up call so that we will never again ask, “How many more children have to die?” Nothing can justify this preventable tragedy to the parents and families of their murdered beloved ones. The time has come to halt the unrelentless chipping away of our mental health care services and quality of care for mental illness, to educate the community about severe mental illness, and to implement strict controls on access to firearms.

Rochelle Caplan, M.D. is UCLA Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry and past Director the UCLA Pediatric Neuropsychiatry Program. She is co-author of “How many more questions?” : Techniques for Clinical interviews of Young Medically Ill Children (Oxford University Press) and author of Manual for Parents of Children with Epilepsy (Epilepsy Foundation). She studies thinking and behavior in pediatric neurobehavioral disorders (schizophrenia, epilepsy, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, high functioning autism) and related brain structure and function; unmet mental health need in pediatric epilepsy; and pediatric non-epileptic seizures.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post How many more children have to die? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers