Oxford University Press's Blog, page 997

December 13, 2012

Beethoven’s creativity in the 21st century

Our fascination with creativity is a timeless and universal phenomenon. Since Greek antiquity, its most telling embodiment has been Prometheus: that heroic benefactor of humanity who stole the fire whose vital sparks sustain science and the arts. In more modern times, it is the fire of the imagination that is understood to illuminate and guide the creative mind, transforming the conventions of culture. For Ludwig van Beethoven, at the threshold of the nineteenth century, the challenge retained its force: his first major piece for the stage was the ballet music to “The Creatures of Prometheus,” op. 43. That work in turn became the stepping-stone to a pivotal masterpiece of fiery daring: the Eroica Symphony, completed in 1804.

In the world of art, the notion of a work emerging through long toil and unfailing vision is perhaps most readily associated with sculptors such as Michelangelo or Rodin. A prolonged creative process with intermediate stages in the form of models, studies, sketches, and earlier versions, is illustrated in the work of Leonardo da Vinci and many others. Among writers, one thinks of Goethe’s long preoccupation with Wilhelm Meister or Faust, or Jean Paul Richter’s prolonged work on his novels.

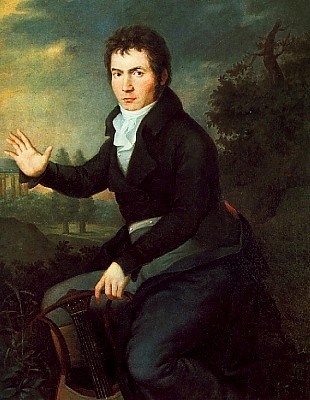

Portrait of Ludwig van Beethoven by Joseph Willibrord Mähler, 1804-1805. Vienna Museum.

Beethoven’s labors on major projects could extend over many years and even decades of his life, with certain compositions serving as stepping-stones toward larger comprehensive efforts. Thus the Choral Fantasy, op. 80, from 1808, acted as a springboard in the achievement of the choral finale of the Ninth Symphony, completed in 1824. Beethoven himself pointed out the affinity, describing the finale as “a setting of the words of Schiller’s immortal ‘Lied an die Freude’ in the same way as my pianoforte fantasia with chorus, but on a far grander scale.”In the age of Romanticism, the emphasis on originality and the cult of genius raised the stakes of artistic creativity, and propagated the image of the suffering artist-hero. Beethoven’s reputation for defiant independence fit this heroic image and his handicapped status as a “deaf seer,” in Wagner’s words, made it stick. With Beethoven’s worsening deafness came an inevitable retreat from the concert platform as well as an increasing social isolation. His loss of hearing also impacted his composing methods. As he grew older, Beethoven relied more on written musical sketches and drafts. As a young composer who was also an active keyboard virtuoso and skilled improviser, Beethoven could immediately test ideas at the piano. Increasingly, such exploratory activity was transferred from the piano to his sketchbooks and thereby captured on paper, with the musical sketches sometimes taking on the appearance of notated improvisations.

The legacy of Beethoven’s sketchbooks offers us a rare opportunity to gaze into the workshop of one of the greatest artists. Beethoven made thousands of pages of sketches and drafts for his music in addition to the finished scores, many of which are also full of his changes and corrections. This process of writing traced both the swift arc of the imagination and the very conscious deliberation demanded by specific compositional problems. His unusual and consistent reliance on these papers and attachment to them after use have preserved a detailed record of the creative process.

Beethoven’s commitment to sketching his music was noticed and remarked upon by his contemporaries. Ignaz von Seyfried, for instance, reported that Beethoven “was never found on the street without a small note-book in which he was wont to record his passing ideas. Whenever conversation turned on the subject he would parody Joan of Arc’s words: “I dare not come without my banner!”

How can we best do justice to Beethoven’s legacy and influence in the present day? One imperative is to seek to overcome narrow or overspecialized approaches that sever history from theory, and performance from aesthetics. Such pigeonholing is often encouraged by institutional structures, but often does not help us to grasp the magnitude of Beethoven’s achievement and continuing cultural importance. Beethoven once wrote characteristically about the need for “freedom and progress. . . in the world of art as in the whole of creation.” To refer to his own artistic goal in this context he coined the term Kunstvereinigung or “artistic unification.” Today, two-hundred forty-two years after his birth, Beethoven scholarship is entering its most vigorous stage yet, influencing our contemporary musical and cultural life.

William Kinderman is Professor of Musicology at the University of Illinois – Champaign-Urbana. His books include Beethoven’s “Diabelli” Variations (OUP, 1987), ed., Beethoven’s Compositional Process (Nebraska, 1991), Beethoven (OUP and California, 1995), ed., The Second Practice of Nineteenth-Century Tonality (Nebraska, 1996), Artaria 195: Beethoven’s Sketchbook for the ‘Missa solemnis’ and the Piano Sonata in E Major, Opus 109 (Illinois, 3 vols., 2003), ed. (with Katherine Syer), A Companion to Wagner’s “Parsifal” (Camden House, 2005), ed., The String Quartets of Beethoven (Illinois, 2006), and Mozart’s Piano Music (OUP, 2006). He is also an accomplished pianist whose recordings have been met with global acclaim; his CDs of Beethoven’s last sonatas and Diabelli Variations have appeared with Arietta Records.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Beethoven’s creativity in the 21st century appeared first on OUPblog.

Samuel Johnson and human flight

By Thomas Keymer

One doesn’t associate Samuel Johnson, whose death 228 years ago today ended his lengthy domination of the literary world, with the history of aviation. But ballooning was a national obsession in Johnson’s last year, and he was caught up in the craze despite himself. Several early experiments ended badly (one prototype was pitchforked to shreds as it landed by terrified peasants), but the first manned flights took place successfully in Paris in autumn 1783. Soon the London Chronicle was reporting that “Montgolfier mania” was “endemial both in France and England,” and plans were under way to repeat the exercise in Britain. Johnson researched the enabling technology as reports flowed in from Paris, and a year later he was in Oxford when James Sadler—the doughty Richard Branson of his day—made his celebrated ascent from the University Botanical Garden on 17 November 1784, flying 20 gut-wrenching miles to Aylesbury. Johnson was now severely ill, and the best he could do was witness the event by proxy: “I sent Francis [his beloved Jamaican manservant and heir] to see the Ballon fly, but could not go myself.”

The likelihood is that by this stage he didn’t much mind. Initially, Johnson saw huge potential in balloons for advancing human knowledge, and subscribed to a scientifically motivated scheme for high-altitude flight, which, he wrote, would “bring down the state of regions yet unexplored.” He was fascinated by thoughts of the view from above, though he couldn’t imagine seeing “the earth a mile below me, without a stronger impression on my brain than I should like to feel.” But in time Johnson grew more sceptical about the value of balloons—fragile, combustible, impossible to direct—for either transportation or science, and disease preoccupied him instead: “I had rather now find a medicine that can ease an asthma.” He never makes the analogy explicit, but it’s clear from his last letters that, consciously or otherwise, he came to associate his bloated, dropsical body with a sinking balloon, and his difficulty in breathing with an aeronaut’s struggle to stay inflated. In a gloomy, earthbound message just weeks before death, he seems to glimpse the void in Montgolfier shape. “You see some ballons succeed and some miscarry, and a thousand strange and a thousand foolish things,” he tells the enviably youthful, mobile Francesco Sastres: “But I see nothing; I must make my letter from what I feel, and what I feel with so little delight, that I cannot love to talk of it.”

The likelihood is that by this stage he didn’t much mind. Initially, Johnson saw huge potential in balloons for advancing human knowledge, and subscribed to a scientifically motivated scheme for high-altitude flight, which, he wrote, would “bring down the state of regions yet unexplored.” He was fascinated by thoughts of the view from above, though he couldn’t imagine seeing “the earth a mile below me, without a stronger impression on my brain than I should like to feel.” But in time Johnson grew more sceptical about the value of balloons—fragile, combustible, impossible to direct—for either transportation or science, and disease preoccupied him instead: “I had rather now find a medicine that can ease an asthma.” He never makes the analogy explicit, but it’s clear from his last letters that, consciously or otherwise, he came to associate his bloated, dropsical body with a sinking balloon, and his difficulty in breathing with an aeronaut’s struggle to stay inflated. In a gloomy, earthbound message just weeks before death, he seems to glimpse the void in Montgolfier shape. “You see some ballons succeed and some miscarry, and a thousand strange and a thousand foolish things,” he tells the enviably youthful, mobile Francesco Sastres: “But I see nothing; I must make my letter from what I feel, and what I feel with so little delight, that I cannot love to talk of it.”

Yet there’s also a sense in which Johnson had been talking of balloons for decades. It’s with a fantasy of aerial spectatorship—“Let observation with extensive view / Survey mankind, from China to Peru”—that his poem The Vanity of Human Wishes (1749) begins, as though generalizing about the human condition meant taking, almost literally, a bird’s eye view. His philosophical tale Rasselas (1759) uses human flight to address large questions about ambition and power. The hapless inventor of a flying mechanism enthuses to Rasselas about the philosophical pleasure with which he now, “furnished with wings, and hovering in the sky, would see the earth, and all its inhabitants, rolling beneath him.” Inevitably, the wings then fail to keep him aloft, though when he plunges into a lake—with neat Johnsonian irony—they keep him afloat. This is not only a warning about individual overreach, however. It also lets Johnson consider the implications of flight for global power. Before his embarrassing swim, the inventor assures Rasselas that he will never explain aviation to others, “for what would be the security of the good, if the bad could at pleasure invade them from the sky? … A flight of northern savages [the phrase implies not only ancient Goths but also the powers of modern Europe, then waging war for empire] might hover in the wind, and light at once with irresistible violence upon the capital of a fruitful region that was rolling under them.”

When editing Rasselas a few years ago, I was fascinated to see how often Johnson’s signature effect of timeless truth seemed to spring from odd contingencies. Scholars often situate Johnson’s failed aeronaut in mythical and literary traditions, and in this context it was refreshing to find Pat Rogers’s reading of the episode with reference to a historical stuntman and self-styled “flyer” named Robert Cadman. Cadman was a minor celebrity in the midlands of Johnson’s youth, a tightrope-walker whose trick was to slide down cords from steeple-tops, which he did to acclamation until dying from a fall in 1739. There was also a delightful related source for Johnson’s hovering armies. This was a satirical elegy on Cadman in a magazine for which Johnson was working at the time, which imagines airborne invasion of a rival power by squadrons of flying Cadmans: “An army of such wights to cross the main, / Sooner than Haddock’s fleet, shou’d humble Spain.” (Yes, there really was an Admiral Haddock.)

James Boswell tells a story from 1781 in which, claiming never to have re-read Rasselas since publication, Johnson snatches a copy he sees and turns avidly to a related passage that was now more telling than ever. Again it concerns war and empire, specifically the geopolitical consequences of technological advance in “the northern and western nations of Europe; the nations which are now in possession of all power and all knowledge; whose armies are irresistible, and whose fleets command the remotest parts of the globe.” That technology brings power is not, in itself, an unfamiliar insight. Theoreticians of war from Clausewitz to Virilio have explored its implications, and the basic point would not have been news to the tribesmen crushed by Hittite chariots four millennia ago. Yet Johnson gives it an eloquence all his own, and perhaps he still had Rasselas in mind when he saw—or almost saw—Sadler’s balloon in Oxford three years later, harbinger of airborne blitzkrieg and surgical strikes.

Thomas Keymer is Chancellor Jackman Professor of English at the University of Toronto, where he is also affiliated with University College and with the Collaborative Program in Book History and Print Culture at Massey College. He is the editor of the Oxford World’s Classics edition of The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abissinia by Samuel Johnson. Rasselas is an established classic, often compared to Voltaire’s Candide, Rasselas is perhaps its author’s most creative work.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: An exact representation of Mr Lunardi’s New Balloon as it ascended with himself 13 May 1785 © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without explicit permission of the British Museum.

The post Samuel Johnson and human flight appeared first on OUPblog.

How Nazi Germany lost the nuclear plot

When the Nazis came to power in Germany in 1933, neither the Atomic Bomb nor the Holocaust were on anybody’s agenda. Instead, the Nazi’s top aim was to rid German culture of perceived pollution. A priority was science, where paradoxically Germany already led the world. To safeguard this position, loud Nazi voices, such as Nobel laureate Philipp Lenard, complained about a ‘massive infiltration of the Jews into universities’.

The first enactments of a new regime are highly symbolic. The cynically-named Law for the Restoration of the Civil Service, published in April 1933, targeted those who had non-Aryan, ‘particularly Jewish’, parents or grandparents. Having a single Jewish grandparent was enough to lose one’s job. Thousands of Jewish university teachers, together with doctors, lawyers, and other professionals were sacked. Some found more modest jobs, some retired, some left the country. Germany was throwing away its hard-won scientific supremacy. When warned of this, Hitler retorted ‘If the dismissal of [Jews] means the end of German science, then we will do without science for a few years’.

Why did the Jewish people have such a significant influence on German science? They had a long tradition of religious study, but assimilated Jews had begun to look instead to a radiant new role-model. Albert Einstein was the most famous scientist the world had ever known. As well as an icon for ambitious young students, he was also a prominent political target. Aware of this, he left Germany for the USA in 1932, before the Nazis came to power.

How to win friends and influence nuclear people

The talented nuclear scientist Leo Szilard appeared to be able to foresee the future. He exploited this by carefully cultivating people with influence. In Berlin, he sought out Einstein.

Like Einstein, Szilard anticipated the Civil Service Law. He also saw the need for a scheme to assist the refugee German academics who did not. First in Vienna, then in London, he found influential people who could help.

Just as the Nazis moved into power, nuclear physics was revolutionized by the discovery of a new nuclear component, the neutron. One of the main centres of neutron research was Berlin, where scientists saw a mysterious effect when uranium was irradiated. They asked their former Jewish colleagues, now in exile, for an explanation.

The answer was ‘nuclear fission’. As the Jewish scientists who had fled Germany settled into new jobs, they realized how fission was the key to a new source of energy. It could also be a weapon of unimaginable power, the Atomic Bomb. It was not a great intellectual leap, so the exiled scientists were convinced that their former colleagues in Germany had come to the same conclusion. So, when war looked imminent, they wanted to get to the Atomic Bomb first. One wrote of ‘the fear of the Nazis beating us to it’.

Szilard, by now in the US, saw it was time to act again. He knew that President Roosevelt would not listen to him, but would listen to Einstein, and wrote to Roosevelt over Einstein’s signature.

When a delegation finally managed to see him on 11 October 1939, Roosevelt said “what you’re after is to see that the Nazis don’t blow us up”. But nobody knew exactly what to do. The letter had mentioned bombs ‘too heavy for transportation by air’. Such a vague threat did not appear urgent.

But in 1940, German Jewish exiles in Britain realized that if the small amount of the isotope 235 in natural uranium could be separated, it could produce an explosion equivalent to several thousand tons of dynamite. Only a few kilograms would be needed, and could be carried by air. The logistics of nuclear weapons suddenly changed. Via Einstein, Szilard wrote another Presidential letter. On 19 January 1942, Roosevelt ordered a rapid programme for the development of the Atomic Bomb, the ‘Manhattan Project’.

Across the Atlantic, the Germans indeed had seen the implications of nuclear fission. But its scientific message had been muffled. Key scientists had gone. Germany had no one left with the prescience of Szilard, nor the political clout of Einstein. The Nazis also had another priority. On 20 January, one day after Roosevelt had given the go-ahead for the Atomic Bomb, a top-level meeting in the Berlin suburb of Wannsee outlined a “final solution of the Jewish Problem”. Nazi Germany had its own crash programme.

US crash programme – on 16 July 1945, just over three years after the huge project had been launched, the Atomic Bomb was tested in the New Mexico desert.

Nazi crash programme – what came to be known as the Holocaust rapidly got under way. Here a doomed woman and her children arrive at the specially-built Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination centre.

As such, two huge projects, unknown to each other, emerged simultaneously on opposite sides of the Atlantic. The dreadful schemes forged ahead, and each in turn became reality. On two counts, what had been unimaginable no longer was.

Gordon Fraser was for many years the in-house editor at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, in Geneva. His books on popular science and scientists include Cosmic Anger, a biography of Abdus Salam, the first Muslim Nobel scientist, Antimatter: The Ultimate Mirror, and The Quantum Exodus. He is also the editor of The New Physics for the 21st Century and The Particle Century.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: Atomic Bomb tested in the New Mexico desert. Photograph courtesy of Los Alamos National Laboratory; Auschwitz-Birkenau, alte Frau und Kinder, Bundesarchiv Bild, Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How Nazi Germany lost the nuclear plot appeared first on OUPblog.

December 12, 2012

Drinking vessels: ‘bumper’

Some time ago, I devoted three posts to alcoholic beverages: ale, beer, and mead. It has occurred to me that, since I have served drinks, I should also take care of wine glasses. Bumper is an ideal choice for the beginning of this series because of its reference to a large glass full to overflowing. It is a late word, as words go: no citation in the OED predates 1677. If I am not mistaken, the first lexicographer to include it in his dictionary was Samuel Johnson (1755). For a long time bumper may have been little or not at all known in polite society. Even Nathan Bailey (1721 and 1730) missed it. But once it surfaced in dictionaries, guesswork about its origin began.

Johnson derived bumper from bum “being prominent.” Etymology was not his forte (to put it mildly), and the source of the consonant p hardly bothered him. Of the revisions of Johnson’s work especially serious was the one by the Reverend H. J. Todd (1827). Although later scholars derided Todd’s etymologies, his explanations were not always useless, despite the fact that he had no notion of the progress historical linguistics had made by 1827. Be that as it may, to discover the origin of seventeenth-century English slang (and I assume bumper was slang), one can dispense with the facts of Indo-European and even of Old English. Todd called Johnson’s conjecture far-fetched, offered none of his own, and only said that others had traced bumper to bumbard ~ bombard. It is most irritating that he did not indicate who the “others” were. I have been unable to find his authority and will be very pleased if someone enlightens me on this point.

Bombard, a word known to Shakespeare and his contemporaries, meant “cannon” and (on account of its size or form?) “leather jug or bottle for liquor.” For a long time Skeat had sufficient trust in this etymology. Bumper, he said, appeared in English just as the older bombard, a drinking vessel, disappeared and was “a corruption of it.” This hypothesis fails to convince. A jug or a bottle for liquor is not a glass, and it remains unclear why a word, evidently in common use, should have been “corrupted.” Nevertheless, the bombard-bumper etymology appeared in numerous good dictionaries, though, surprisingly, Skeat’s early competitors Eduard Mueller and Hensleigh Wedgwood passed by the word.

Then there were attempts to present bumper as a disguised compound. Such an idea should not be dismissed out of hand. For example, bridal, now understood as an adjective, derives from Old Engl. bryd “bride” and ealu “ale” and meant “ale drinking at a wedding feast.” The indefatigable Charles Mackay, who traced hundreds of English words to Irish Gaelic, explained bumper as the sum of bun “bottom” and barr “top”: bum-barr or bun-parr “full from the bottom to the top.” A somewhat more reasonable theory looked upon bumper as a borrowing from French and decomposed it into bon “good” and père or Père “father.” A typical statement ran as follows: “When the English were good Catholics, they usually drank the Pope’s health in a full glass after dinner—Au bon Père—whence your bumper.” Perhaps this derivation was first offered in Joseph Spence’s posthumous (1820) Anecdotes, Observations, and Characters, of Books and Men…, an amusing and entertaining book. Spence had no idea when bumper surfaced in English and did not doubt that at the time of the word’s appearance the English were still good Catholics. Nor did he provide any evidence that the rite he mentioned ever existed. (Those with a taste for such reading will also enjoy Samuel Pegge’s Anecdotes of the English Language…, 1844.)

This is a country bumpkin. Bumpkin and bumper are not related.

Soon after the publication of Spence’s Anecdotes Alexander Henderson brought out a volume titled The History of Ancient and Modern Wines (1824), a learned and eminently readable piece of scholarship. Like many of his contemporaries, he occasionally dabbled in etymology. According to him, bumper was “a slight corruption of the old French phrase bon per, signifying a boon companion.” Granted, French pair “one’s equal, peer” had the form per in Old French, but where did Henderson find the collocation bon per “boon companion”? This is the problem with both Mackay and the adherents of the French theory. The etymons they posed do not and did not exist in the alleged lending languages, so that, following their logic, the phrases had to be coined in English from two foreign elements, change their shape, merge, and become opaque simplexes. This chain of events defies belief.

Not unexpectedly, some people thought they had found a tie between bumper and bump up, a rather rare collocation meaning “swell up.” The glass was said to be filled so as to cause the liquid to “bump up” slightly above the rim. Several variations on the bump up theme exist. At this point I need a short digression. Some etymological dictionaries have been written by monomaniacs, as Ernest Weekley called them. They derived all the words of English from several ancient roots or from a few primordial cries, or from one language (Irish Gaelic, Arabic, Hebrew, etc.). Criticizing their labors is a thankless task. By contrast, the authors of some dictionaries were so misguided, even if learned, that one wonders how they managed to produce their monstrosities. One such monster is Words: Their History and Derivation, Alphabetically Arranged by Dr. F. Ebener and E.M. Greenway, Jr. (Baltimore and London, 1871). Greenway was, apparently, the translator of this hapless work from German, while Ebener may have been a medical doctor. Among the physicians of the past one can find several crazy etymologists. The dictionary caused such an outcry that its publication was discontinued after the letter B. But my experience has taught me to consult all sources, because a heap of muck sometimes contains a grain of precious metal. (Consider also the dust heaps immortalized in Our Mutual Friend.) This is what I found in the short entry Bumper: “After Grimm [sic], a full glass which in toasting is knocked on the table or against another bumper. He compares [sic] with bomber-nickel.” (It is so easy to translate this text back into German!)

What is a bomber-nickel? And where did Grimm (I assume, Jacob Grimm) say it? His multivolume Deutsche Grammatik has a word index, compiled by Karl Gustav Andresen and published in 1865, but bumper is not in it. Once again I am turning to the assistance of our correspondents. Perhaps they will be able to find the relevant place in Jacob Grimm’s other books or Kleinere Schriften. I cannot imagine that Ebener made up the reference. The OED suggested cautiously that bumper is connected with bumping and its synonym thumping “very large.” Quite possibly, that’s all there is to it. Yet a link seems to be missing, namely some reference to drinking.

The short-lived adjective bumpsy (bumpsie) “drunk,” with an obscure suffix seemingly borrowed from tipsy, has often been cited by those who looked for the origin of bumper. I wonder whether bump up at one time also meant “guzzle” or that the noun bumper “drunkard” existed in colloquial use. Bumper “full glass” may, as suggested above, have been avoided by Samuel Johnson’s closest predecessors because it was current only as occasional slang, even though Johnson did not call the word low (an epithet of which he was fond). Bumper “full glass,” coexisting with bumper “drunkard,” is possible. For instance, a reader is someone who reads and a book for reading. Also, bump “drink heavily,” a homonym of bump “strike” and bump “bulge out, protrude,” may have had some currency as an expressive doublet of the little-known verb bum “consume alcohol.” Verbs ending in -mp (jump, thump, slump, dump, and of course bump) are invariably expressive. I wish it were possible to show that slum, a word of undiscovered origin, is in some way connected with slump!

The etymology of bumper is simple (not a “corruption” or a disguised compound), but, unfortunately, some details have been lost along the way. Let us not des-pair. Good wine needs no bush, so au bon père!

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Themas well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: A portrait of a man aiming a shotgun. Critical focus on tip of gun. Isolated on white. Photo by steele2123, iStockphoto.

The post Drinking vessels: ‘bumper’ appeared first on OUPblog.

A holiday maze

By Georgia Mierswa

Ah, the holidays. A time of leisure to eat, drink, be merry, and read up on the meaning of mistletoe in Scandinavian mythology…

Taken from the Oxford Index’s quick reference overview pages, the descriptions of the wintry-themed words above are not nearly as simplistic as you might think — and even more intriguing are the related subjects you stumble upon through the Index’s recommended links. I’ll never look at a Christmas tree the same way again.

ICE-SKATING

In its simplest form dates back many centuries, [done] with skates made out of animal bones….

→ Sonja Henie (1912 – 1969)

Norwegian figure skater. In 1923 she was Norwegian champion, between 1927 and 1936 she held ten consecutive world champion titles, and between 1928 and 1936 she won three consecutive Olympic gold medals. In 1938 she began to work in Hollywood, in, among others, the film Sun Valley Serenade (1941)…

→ Sun Valley Serenade

… Such was the popularity of the Glenn Miller Band by 1941 that it just had to appear in a film, even if the story was as light as a feather…

YULE

…The name comes from Old English gēol(a) ‘Christmas Day’; compare with Old Norse jól, originally applied to a heathen festival lasting twelve days, later to Christmas…

→ Snorri Sturluson (1178 – 1241)

Icelandic historian and poet. A leading figure of medieval Icelandic literature, he wrote the Younger Edda or Prose Edda and the Heimskringla, a history of the kings of Norway from mythical times to the year 1177…

CHRISTMAS TREE

It is generally assumed that this indisputably German custom was introduced to Britain by Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert, but this is only partly true. The British royal family had had regular Christmas trees since the days of Princess Charlotte of Mecklenberg Strelitz…But it was certainly due to active promotion by Victoria and Albert that the fashion for trees spread so remarkably fast, at least among the better-off…

→ Christmas tree (slang)

– a nuclear missile onboard a submarine.

– a control room or cockpit’s panel of indicator lights, green (good) and red (bad).

FATHER CHRISTMAS

– …Gives news of Christ’s birth, and urges his hearers to drink: ‘Buvez bien par toute la compagnie, Make good cheer and be right merry.’

– There were Yule Ridings in York (banned in 1572 for unruliness), where a man impersonating Yule carried cakes and meat through the street.

→ Clement C. Moore (1779 – 1863)

…Professor of Biblical learning and author of the poem popularly known as “’Twas the Night Before Christmas,” published anonymously in the Troy Sentinel (Dec. 23, 1823), widely copied, and reprinted in the author’s Poems (1844). The poem’s proper title is “A Visit from St. Nicholas.”

WASSAIL

– A festive occasion that involves drinking.

– It derives from the Old Norse greeting ves heill, ‘be in good health’.

→ Christmas

… The date was probably chosen to oppose the pagan feast of the Natalis Solis Invicti by a celebration of the birth of the ‘Sun of Righteousness’…

SNOWMAN

(1978) Raymond Briggs’s wordless picturebook uses comic‐strip techniques to depict the relationship between a boy and a snowman who comes alive in the night but melts the next day….

→ Abominable Snowman

A popular name for the yeti, recorded from the early 1920s.

→ Yeti

A large hairy creature resembling a human or bear, said to live in the highest part of the Himalayas…

…comes from Tibetan yeh-teh ‘little manlike animal’.

MISTLETOE

– Traditionally used in England to decorate houses at Christmas, when it is associated with the custom of kissing under the mistletoe.

– In Scandinavian mythology, the shaft which Loki caused the blind Hod to throw at Balder, killing him, was tipped with mistletoe, which was the only plant that could harm him.

– ‘The Mistletoe Bough’ a ballad by Thomas Bayly (1839), which recounts the story of a young bride who during a game hides herself in a chest with a spring-lock and is then trapped there; many years later her skeleton is discovered.

→ Evergreens

A high proportion of the plants important in folk customs are evergreen — a fact which can be seen either in practical or symbolic terms. Folklorists have usually highlighted the latter, suggesting that at winter festivals they represented the unconquered life-force, and at funerals immortality.

GINGERBREAD

Cake or biscuits flavoured with ginger and treacle, often baked in the shape of an animal or person, and glazed.

→ Gingerbread

The gilded scroll work and carving with which the hulls of large ships, particularly men-of-war and East Indiamen of the 15th to 18th centuries, were decorated. ‘To take some of the gilt off the gingerbread’, an act which diminishes the full enjoyment of the whole.

GIFT

– …gifts have importance for tax purposes; if they are sufficiently large they may give rise to charges under inheritance tax if given within seven years prior to death (see potentially exempt transfer).

– A gift is also a disposal for capital gains tax purposes and tax is potentially payable.

→ Greek friendship

– Friends, like kin, could be called upon in any emergency; they could be expected to display solidarity, lend general support, and procure co‐operation.

– Friends were therefore supposed to be alike: a friend was ideally conceived of as one’s ‘other self’.

SNOWFLAKE

The result of the growth of ice crystals in a varied array of shapes. Very low temperatures usually result in small flakes; formation at temperatures near freezing point produces numerous crystals in large flakes.

→ Ice crystal

Frozen water composed of crystalline structures, e.g. needles, dendrites, hexagonal columns, and platelets.

→ Diamond dust

Minute ice crystals that form in extremely cold air. They are so small as to be barely visible and seem to hang suspended, twinkling as they reflect sunlight.

Georgia Mierswa is a marketing assistant at Oxford University Press and reports to the Global Marketing Director for online products. She began working at OUP in September 2011.

The Oxford Index is a free search and discovery tool from Oxford University Press. It is designed to help you begin your research journey by providing a single, convenient search portal for trusted scholarship from Oxford and our partners, and then point you to the most relevant related materials — from journal articles to scholarly monographs. One search brings together top quality content and unlocks connections in a way not previously possible. Take a virtual tour of the Index to learn more.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A holiday maze appeared first on OUPblog.

Robert Browning in 2012

This year marked the bicentenary of the birth of the Victorian poet Robert Browning in 1812, although this news might come as something of a surprise. The bicentenary of Browning’s contemporary Charles Dickens was celebrated with so many exhibitions, festivals, and other events that an official Dickens 2012 group was set up to co-ordinate and keep track of them all. The writings of Alfred Tennyson, Browning’s (consistently more popular) rival, also cropped up in some high-profile places throughout the year. But although academic specialists and other Browning enthusiasts organised conferences and special publications in 2012, media commentators and cultural institutions remained almost wholly silent about the Browning anniversary.

There are many possible reasons for this silence. There’s the issue of religion: Browning’s robust Christian faith, and his love of abstruse theological speculation, are perhaps less congenial to twenty-first-century tastes than the yearning doubt of Tennyson or the pious sentimentality of Dickens. Browning’s habit of writing poems about arcane subjects (such as the thirteenth-century troubadour Sordello or the sixteenth-century alchemist Paracelsus) might also alienate readers. The reason might, however, be something even more fundamental: Browning’s poetry is difficult, and discomfiting, to read. When Browning was buried in Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey on 31 December 1889, Henry James wrote that “a good many oddities and a good many great writers have been entombed in the Abbey; but none of the odd ones have been so great and none of the great ones so odd.” For James, Browning’s oddness was an essential part of his poetic achievement. Today, it seems, the general view (if there is a general view on him at all) is that his oddness precludes greatness.

For most of his life, Browning’s oddness was seen by his Victorian contemporaries as the key characteristic of his writing. John Ruskin, for example, wrote to the poet in 1855 to describe the poems in his new book Men and Women as “absolutely and literally a set of the most amazing Conundrums that ever were proposed to me.” Browning’s reply to Ruskin is significant, because it suggests that his difficult style is central to the goals of his poetry: “I know that I don’t make out my conception by my language; all poetry being a putting the infinite within the finite.” This definition of poetry was closely tied to Browning’s views on psychology: throughout his career he was preoccupied with the question of how to fit what he saw as the infinite capacities of the human mind into the finite media of language and poetic form. His answer was to adopt a knotty, convoluted, and tortuous syntax which articulated the difficulty, but also the necessity, of conveying the workings of the mind through the more or less inadequate tools of language.

For most of his life, Browning’s oddness was seen by his Victorian contemporaries as the key characteristic of his writing. John Ruskin, for example, wrote to the poet in 1855 to describe the poems in his new book Men and Women as “absolutely and literally a set of the most amazing Conundrums that ever were proposed to me.” Browning’s reply to Ruskin is significant, because it suggests that his difficult style is central to the goals of his poetry: “I know that I don’t make out my conception by my language; all poetry being a putting the infinite within the finite.” This definition of poetry was closely tied to Browning’s views on psychology: throughout his career he was preoccupied with the question of how to fit what he saw as the infinite capacities of the human mind into the finite media of language and poetic form. His answer was to adopt a knotty, convoluted, and tortuous syntax which articulated the difficulty, but also the necessity, of conveying the workings of the mind through the more or less inadequate tools of language.

Browning’s approach is exemplified in what is arguably his greatest poem, The Ring and the Book (1868-1869), a psychological epic which recounts the events of a seventeenth-century murder case from nine different perspectives. Browning sets out to integrate these conflicting perspectives into an authoritative and morally educational account of the murder, describing them as:

The variance now, the eventual unity,

Which make the miracle. See it for yourselves,

This man’s act, changeable because alive!

Action now shrouds, now shows the informing thought.

The poem’s concern is not with the murder itself, “this man’s act”, but with tracing “the informing thought,” the motive behind the act. This poetic analysis of thought, Browning argues, enables the synthesis of conflicting accounts into an “eventual unity,” and the dense style of his verse is a key element of this process. “Art,” he states “may tell a truth / Obliquely, do the thing shall breed the thought.” By testing and confounding his readers, Browning’s difficult (and odd) poetry invites them to think carefully about the minds of other people, breeding new thoughts and telling oblique truths.

In The Ring and the Book Browning addresses the “British Public, ye who like me not.” The publication of this poem, however, marked a sea change in Victorian opinions of the poet. In the 1870s and 1880s his writing was admired simultaneously for its evident Christianity and its intellectual richness, and he was venerated as a sage and a moral teacher by the Browning Society which was founded in 1881 to study and champion his work. He was also celebrated, by Henry James and by Modernists such as Ezra Pound, as (in James’s words) “a tremendous and incomparable modern.” In 2012, though, Browning’s modernity and relevance have not been sufficiently emphasised. This is a shame, because, in his psychological sophistication and in his awareness of the complexities and limitations of language, he still has truths to tell to the British public, who like him not. Those truths, and Browning’s poems, might be oblique and difficult, but they’re worth the effort.

Gregory Tate is Lecturer in English Literature at the University of Surrey. His book, The Poet’s Mind: The Psychology of Victorian Poetry 1830-1870, was published by OUP in November 2012. You can follow him on Twitter @drgregorytate.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Robert Browning. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Robert Browning in 2012 appeared first on OUPblog.

December 11, 2012

The art of science

Are art and science so different? At the deepest levels, the overlap is stunning. The artist wakes us from the slumber of ordinary existence by uncovering a childlike wonder and awe of the natural environment. The same magical processes occur when a scientist grasps the mysteries of nature, and by doing so, ultimately shows a graceful interconnectedness.

The intuition of the artist is no different from the hunches of a scientist. Both draw from unconscious realms where inner voices and soaring images provide sustenance for the imagination. Distractions and blind alleys often prevent the grasping of new visions or unraveling of complex social problems. Instincts and other primordial sources can break these intellectual and emotional barriers, and provide unparalleled insights into the vital nature of reality.

Both artist and scientist are revolutionaries, trying to change our perceptions and understanding of the world. Sometimes the fuel is no more than an outrage that “this must change”. Their paths often begin with a gnawing realization that something is askew in nature, which sets the traveler on a journey into the unknown to find what is missing, such as bringing about a more just and humane society.

Pansy (Viola x wittrockiana) at the Winterthur Country Estate. Photo by Derek Ramsey, (c) 2007. GNU Free Documentation License 1.2.

The bane of artists and scientists is existing paradigms and ideologies, which represent conventional and at times suffocating norms. The status quo is interwoven with concentrated power, which can corrupt and defeat attempts to overthrow dominant values, philosophies, and social inequities. Financial benefactors offer rewards that reinforce a social hierarchy resistant to change. Therefore, when peering into the world with new lenses, like Galileo, radical new insights and discoveries are often challenged and opposed by those reifying mainstream standards and mores.Artists and scientists use similar strategies and tactics to confront power structures that perpetuate institutional stagnation. Resources need to be identified and mobilized to buttress dreams and inspiration, to weather the assaults of critiques and forces inimical to new perspectives. Focus and commitment against seemingly insurmountable opposition can be sustained and validated by nurturing coalitions, including professional colleagues, friends, and family members. These cadres of supportive counter-change agents often provide a life-affirming antidote to the isolation and even animosity that can be engendered by radical transformative ideas and solutions to aesthetic and social issues. New professional and community coalitions can provide alternative sources of meaning by challenging existing reference groups and standards, and by validating innovative ways of approaching formerly intractable problems.

Suffice it to say, scientists and artists are often greeted with suspicion, disbelief, or even outright disdain for their offerings. Some retreat whereas others persist in sharing their new insights and knowledge in the public domain, regardless of the ego injuries and accruing disrespect. These prophets often feel as if they are lost in a dense fog or dark forest, but their enduring resolve to pursue an unconventional line of research or provide an alternative glimpse of reality represents a sustaining force. It is not fleeting happiness nor a drunken sense of wild abandon that uphold these commitments, but rather a deep sense of conviction and faith about one’s liberating vision.

Finally, learning, experimentation, feedback, and refinement are the backbone of both the sciences and the arts. Decades of painstaking analysis and observation were critical in the development of Darwin’s grand theory of evolution. The dissection of corpses and countless sketches polished and unleashed Michelangelo’s genius in capturing the human spirit in exquisite detail. Sweat and toil nurture the fertile imagination and fine tune the ability to peer through nature’s veil and uncover eternal truths that lead to Eureka moments of exhilarating discovery.

Spectacular gifts await us as we work to unravel the DNA of equality, faith, love, and compassion, and thereby usher in a world saturated with meaning, surrounded by creative rapturous forces. True research has a soul of an artist.

Leonard A. Jason is a Professor of Clinical and Community Psychology at DePaul University, and the Director of the Center for Community Research. For 38 years, he has been studying the interplay between creative forces and the process of community change. He is the author of Principles of Social Change (2013), published by Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The art of science appeared first on OUPblog.

Life in a brewery

What kind of crazy things happen at a brewery bar? What is some of the interesting stuff you can do with beer? What’s proper beer etiquette? If you don’t like beer, what beer should you try? How do you become a brewer? How do you break into the brewing industry?

Interviews with the Eric Peck, Brooklyn Brewery Tour Guide and Bartender, and Tom Price, Brooklyn Brewery Brewer and Lab Manager, reveal life inside a brewery. Editor-in-Chief of The Oxford Companion to Beer, Garrett Oliver is brewmaster of the Brooklyn Brewery and is the foremost authority on beer in the United States.

Interview with the Brooklyn Brewery Bartender

Click here to view the embedded video.

Interview with a Beer Brewer and Lab Manager

Click here to view the embedded video.

Garrett Oliver, editor of The Oxford Companion to Beer, is the Brewmaster of the Brooklyn Brewery and author of The Brewmaster’s Table: Discovering the Pleasures of Real Beer with Real Food. He has won many awards for his beers, is a frequent judge for international beer competitions, and has made numerous radio and television appearances as a spokesperson for craft brewing.

The Oxford Companion to Beer is the first major reference work to investigate the history and vast scope of beer, featuring more than 1,100 A-Z entries written by 166 of the world’s most prominent beer experts. It is first place winner of the 2012 Gourmand Award for Best in the World in the Beer category, winner of the 2011 André Simon Book Award in the Drinks Category, and shortlisted in Food and Travel for Book of the Year in the Drinks Category. View previous Oxford Companion to Beer blog posts and videos.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only food and drink articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Life in a brewery appeared first on OUPblog.

The Beethoven question: How does a musician cope with hearing loss?

Hearing is clearly the most important sense for a musician, particularly a composer, so the trauma of experiencing difficulties with this sense is hard to imagine. Beethoven famously suffered deteriorating hearing for much of his adult life; an affliction which brought him to despair at times. The cause of his deafness is still unknown, although much speculated upon, but the composer’s feelings about his situation are well-documented: Beethoven kept ‘Conversation Books’ full of discussions of his music and other issues which give a unique insight into his thoughts, and in a letter to his brothers (the Heiligenstadt Testament) he wrote a heart-wrenching description of his sense of despair and isolation caused by his inability to hear.

Despite his catastrophic loss of hearing Beethoven continued to compose — producing some of the greatest works in Western musical history. So how was this possible? How can a musician, particularly a composer, continue without full, or even hyper-sensitive, hearing?

We can get a modern day insight from Michael Berkeley — one of OUP’s composers who, over recent years, has been struggling with hearing troubles himself. Berkeley’s hearing damage was the result of a blocked ear, brought on by a fairly minor cold, which has caused irreparable nerve damage. These days there’s better help available to sufferers of hearing loss. However, sound distortion remains a problem, and hearing aids can only help so far, as Berkeley explains:

We can get a modern day insight from Michael Berkeley — one of OUP’s composers who, over recent years, has been struggling with hearing troubles himself. Berkeley’s hearing damage was the result of a blocked ear, brought on by a fairly minor cold, which has caused irreparable nerve damage. These days there’s better help available to sufferers of hearing loss. However, sound distortion remains a problem, and hearing aids can only help so far, as Berkeley explains:

“Music was appallingly distorted, and in fact I couldn’t go to concerts as it was just so painful. I got a condition called hyperacusis, where loud sounds are unbearably painful. I got some very good digital hearing aids which made a great difference to speech, but it can only amplify what I’m already hearing so it didn’t help for music.”

Michael Berkeley explains how he continued to write music:

“If you are trained as a composer you can write in your head: you hear the sounds internally, and you’ve been trained how to get those sounds onto the page without a piano or any intermediary. It’s something you learn to do gradually through lots of hard work and by instinct. The problem is, when the music is played back I can’t comment very usefully: what I hear may not be what the conductor or the rest of the audience hear…it could be my hearing disability is distorting the real sound.

“The extraordinary thing is, I realised after a number of months that I was beginning to hear music more clearly. I remember there was a Haydn string quartet on, and I suddenly realised I was hearing it better: I was so overjoyed that I went to bed with an iPod and played it all night long! Apparently what can happen is that the brain begins to rewire itself. We hear with our brains — the ear is essentially a conduit — so if you have a template of musical knowledge then the brain begins to compensate for the distortions. My brain is learning to reprocess sound, and so it’s like discovering music anew: it’s absolutely wonderful!

“I’ve always thought that less is more. In Beethoven’s late music, particularly the late string quartets, the music is pared down to the absolute essentials, and I now find in my writing, partly because I can hear better when I play it back, that I’m beginning to concentrate much more on the essence of the sound and try to rid it of extraneous notes.

“I do feel that the music I’ve written in these last two years is actually as good as everything I’d written up until then: hopefully better.”

Michael Berkeley is the composer of a substantial number of highly acclaimed works, including three operas which have been produced in Europe, America and Australia. In addition to having been an associate composer to both the Scottish Chamber Orchestra and the BBC National Orchestra of Wales, Berkeley has had performances of his works given by many of the world’s finest orchestras, ensembles, soloists and opera companies, and many of his works have been released on CD. He is currently composing an anthem for the service of enthronement of Archbishop of Canterbury-elect, Justin Welby, in March 2013.

Anwen Greenaway is a Promotion Manager in Sheet Music at Oxford University Press. Read her previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The Beethoven question: How does a musician cope with hearing loss? appeared first on OUPblog.

December 10, 2012

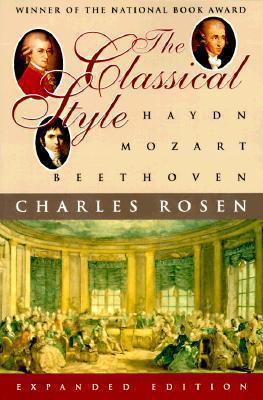

In memoriam: Charles Rosen

Charles Rosen, a titan of the music world, passed away on Sunday. He was a fine concert pianist, groundbreaking musicologist, and a thoughtful critic who wrote prolifically, including regular articles for the New York Review of Books, not just on music but on its broader cultural contexts. We’re excerpting his entry in Grove Music Online by Stanley Sadie below.

Rosen, Charles (Welles)

(b New York, 5 May 1927). American pianist and writer on music. He started piano lessons at the age of four and studied at the Juilliard School of Music between the ages of seven and 11. Then, until he was 17, he was a pupil of Moriz Rosenthal and Hedwig Kanner-Rosenthal, continuing under Kanner-Rosenthal for a further eight years. He also took theory and composition lessons with Karl Weigl. He studied at Princeton University, taking the BA (1947), MA (1949) and PhD (1951), in Romance languages. Some of his time there was spent in the study of mathematics; his wide interests also embrace philosophy, art and literature generally. After Princeton he had a spell in Paris, and a brief period of teaching modern languages at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. But in the year of his doctorate he was launched on a pianist’s career, when he made his New York début and the first complete recording of Debussy’s Etudes. Since then he has played widely in the USA and Europe. He joined the music faculty of the State University of New York at Stony Brook in 1971.

As a pianist, Rosen is intense, severe and intellectual. His playing of Brahms and Schumann has been criticized for lack of expressive warmth; in music earlier and later he has won consistent praise. His performance of Bach’s Goldberg Variations is remarkable for its clarity, its vitality and its structural grasp; he has also recorded The Art of Fugue in performances of exceptional lucidity of texture. His Beethoven playing (he specializes in the late sonatas, particularly the Hammerklavier) is notable for its powerful rhythms and its unremitting intellectual force. In Debussy his attention is focussed rather on structural detail than on sensuous beauty. He is a distinguished interpreter of Schoenberg and Webern; he gave the première of Elliott Carter’s Concerto for piano and harpsichord (1961) and has recorded with Ralph Kirkpatrick; and he was one of the four pianists to commission Carter’s Night Fantasies (1980). He has played and recorded sonatas by Boulez, with whom he has worked closely. His piano playing came to take second place to his intellectual work during the 1990s.

Rosen’s chief contribution to the literature of music is The Classical Style. His discussion, while taking account of recent analytical approaches, is devoted not merely to the analysis of individual works but to the understanding of the style of an entire era. Rosen is relatively unconcerned with the music of lesser composers as he holds ‘to the old-fashioned position that it is in terms of their [Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven’s] achievements that the musical vernacular can best be defined’. Rosen then establishes a context for the music of the Classical masters; he examines the music of each in the genres in which he excelled, in terms of compositional approach and particularly the relationship of form, language and style: this is informed by a good knowledge of contemporary theoretical literature, the styles surrounding that of the Classical era, many penetrating insights into the music itself and a deep understanding of the process of composition, also manifest in his study Sonata Forms (1980). The Classical Style won the National Book Award for Arts and Letters in 1972. His smaller monograph on Schoenberg concentrates on establishing the composer’s place in musical and intellectual history and on his music of the period around World War I. Rosen’s interest in the thought and composition processes of the Romantics, also strong, is shown in his Harvard lectures published as The Romantic Generation. He has written many shorter articles, and contributes on a wide range of topics to the New York Review of Books.

Writings

The Classical Style: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven (London and New York, 1971, enlarged 3/1997 with sound disc)

Arnold Schoenberg (New York, 1975/R)

‘Influence: Plagiarism and Inspiration’, 19CM, iv (1980–81), 87–100

Sonata Forms (New York, 1980, 2/1988)

‘The Romantic Pedal’, The Book of the Piano, ed. D. Gill (Oxford, 1981), 106–13

The Musical Languages of Elliot Carter (Washington DC, 1984)

with H. Zerner: Romanticism and Realism: the Mythology of Nineteenth-Century Art (New York, 1984) [rev. articles pubd in The New York Review of Books]

‘Brahms the Subversive’, Brahms Studies: Analytical and Historical Perspectives, ed. G.S. Bozarth (Oxford,1990), 105–22

‘The First Movement of Chopin’s Sonata in B-flat minor, op.35’, 19CM, xiv (1990–91), 60–66

‘Ritmi de tre battute in Schubert’s Sonata in C minor’, Convention in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Music: Essays in Honor of Leonard G. Ratner, ed. W. Allanbrook, J. Levy and W. Mahrt (Stuyvesant, NY,1992), 113–21

‘Variations sur le principe de la carrure’, Analyse musicale, no.29 (1992), 96–106

Plaisir de jouer, plaisir de penser (Paris, 1993) [collection of interviews]

The Frontiers of Meaning: Three Informal Lectures on Music (New York, 1994)

The Romantic Generation (Cambridge, MA, 1995) [based on the Charles Eliot Norton lectures delivered at Harvard; incl. sound disc]

Romantic Poets, Critics, and Other Madmen (Cambridge, MA, 1998)

Critical Entertainment: Music Old and New (Cambridge, MA, 2000) [collection of essays]

Charles Rosen

May 5, 1927 – December 9, 2012

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

The post In memoriam: Charles Rosen appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers