Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1002

November 25, 2012

On animals and tools

Try this experiment: Ask someone to name three tools, without thinking hard about it. This is a parlor game, not a scientific study, so your results may vary, but I’ve done this dozens of times and heard surprisingly consistent answers. The most common is hammer, screwdriver, and saw, in that order.

We seem to share a basic understanding of what tools are and how they’re used. This may be only natural; tools fill our lives. It’s hard to imagine going through your daily routine without them. You can’t brush your teeth or comb your hair; locked doors stay locked; mealtimes, in the preparation and the eating, are messy affairs. As Thomas Carlyle said, “Man is a tool-using animal. Without tools he is nothing, with tools he is all.”

But what does it mean to use tools? This question is of special interest in the area of animal behavior–many non-human animals use and even make tools. In 1980, Benjamin Beck published a book on the subject, Animal Tool Behavior, which catalogues hundreds of examples. (The first edition is out of print and was for a time extraordinarily expensive; when I first started searching for a copy online, I found just one at a price of $626.43. This is sometimes the nature of classic texts.)

Defining tool use is trickier than it might seem. A crow stripping a leaf stem and using it to fish for insects in soft wood? Tool use. Nest making with leaves and twigs? Not tool use. A wasp pounding earth down into a nest with the help of a pebble? Tool use. An otter balancing a rock on its chest to use as an anvil for pounding open molluscs? Tool use. A chimpanzee pounding open a nut on rocky ground? Not tool use. A gorilla using a stick to test the depth of water it intends to wade through? Tool use. A chimpanzee waving a leafy branch to intimidate an intruder? Only ambiguously tool use… The examples go on.

Beck directly took on the issue of definition:

Thus tool use is the external employment of an unattached environmental object to alter more efficiently the form, position, or condition of another object, another organism, or the user itself when the user holds or carries the tool during or just prior to use and is responsible for the proper and effective orientation of the tool.

It’s complex, in part because of the wide range of activities we interpret as tool use — and those we don’t. Notice that a definition purely in terms of physics won’t do. Using a rock held in the hand to break open an egg is tool use, but cracking the egg on a fixed hard surface is not, even if the forces are the same. And the intention of the tool user (Beck’s reference to responsibility) seems relevant as well. Incidental use of objects shouldn’t count. Sometimes a chimpanzee fleeing through the forest canopy might accidentally dislodge sticks that discourage a pursuer, but this doesn’t match our intuitions about tool use. Beck’s definition offers a reasonable compromise on a set of conditions for the behavior.

My students and I were interested in tool use because of its potential implications for robotics. Could the physical and cognitive abilities that enable animals (including humans) to use tools be translated into computational form? We worked with Beck’s definition for a time and eventually developed a simple software architecture that allowed a robot, which we called Canis habilis, to carry out a simple tool-using task.

Alex Wood’s Canis habilis

Click here to view the embedded video.

Our interest in the use of tools by animals remained. We read the literature. We talked with cognitive scientists, animal behavior researchers, and philosophers of mind. I exchanged a few email messages with Dr. Beck. Gradually we developed a new perspective on tool use:

Tool use is the exertion of control over a freely manipulable external object (the tool) with the goal of (1) altering the physical properties of another object, substance, surface or medium (the target, which may be the tool user or another organism) via a dynamic mechanical interaction, or (2) mediating the flow of information between the tool user and the environment or other organisms in the environment.

I won’t go into a detailed motivation for the new definition, but I’ll note that we weren’t able to produce one that’s less complex than Beck’s, and some of the terms we use are themselves hard to define precisely. Do wasps have “goals”? Does “the flow of information” encompass communication? Despite its limitations, the new definition appealed to us, and Thomas Horton (my Ph.D. student at the time) and I eventually placed our work in the journal Animal Behaviour. We were happy. Thomas and I are computer scientists, outsiders to the field of animal behavior, but we’d learned enough to say something interesting. We discovered how interesting by asking experts in the field; our article went through three cycles of peer review before it was accepted.

Just last year Robert Shumaker, Kristina Walkup, and Benjamin Beck published a new edition of his book, which includes a new, refined definition of tool use that supersedes ours. We’re still happy. In some ways, doing research means holding a conversation in the literature, and it’s exciting to play even a small part. It’s the way science moves forward.

Robert St. Amant is an Associate Professor of Computer Science at North Carolina State University, and the author of Computing for Ordinary Mortals, from Oxford University Press. You can follow him on Twitter at @RobStAmant and read his Huffington Post column or his previous OUPblog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only technology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

November 24, 2012

The e-reader over your shoulder

DRM and the new Thought Police

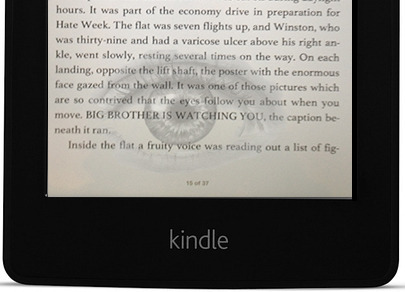

A publisher of digital textbooks has announced a utility that will tell instructors whether their students are actually doing the assigned reading. Billed as a way to spot low-performers and turn them around before it’s too late, CourseSmart Analytics measures which pages of their etexts students have read and exactly how long that took. Then the student e-monitor sends a report card to the teacher. Another exciting example of interactive, digital education? Or a new way to snoop on students outside the classroom?The answer is snooping. And it’s not just electronic textbooks that monitor reading habits. Kindles and iPads track what we read and when, record our bookmarks and annotations, remind us what we searched for last, and suggest other titles we may like. They collect our personal reading data in the name of improving, not our grade, but our digital reading experience, and along the way they may sell the metric of how and what and when we read and use it to improve the company’s bottom line as well.

It’s uncomfortable enough to sense a reader over your shoulder on your morning commute, but every time we fire up an iBook, Kindle, or Nook, there’s an e-reader over our shoulder as well. CCTV may monitor our comings and goings from the outside, but e-readers have spyware that actually looks inside our heads. And e-books provide the ultimate interactive experience: they read us while we are reading them.

Most people don’t seem to mind: they insist it’s no Faustian bargain to trade a little bit of personal data for the convenience of a digital download. Besides, ebooks cost less than printed ones, and didn’t Mark Zuckerberg say that privacy is dead?

And yet we still expect our reading to be private. Librarians will risk jail rather than tell government snoops what their patrons are reading, because the right to read unobserved is a fundamental component of the right to privacy. But when a vendor like Apple or Amazon tracks our reading matter, we don’t invoke Big Brother. Instead, we’re more complacent, accepting this intrusion on our literary solitude because that’s how capitalism is supposed to work.

Another thing that’s different about ebooks besides their lower price is that most of them, including electronic textbooks, are covered by a digital rights management agreement, or DRM. That means we’re actually renting ebooks, not buying them, and that has implications for our reading privacy as well. DRM gives the ebook’s real owners the right to manage their property and to check up on readers to make sure we’re not violating the terms of our lease.

Typically that means we can’t copy passages from an ebook, resell it, lend it to a friend, or give it away. Kindle’s DRM says it all: “You may not sell, rent, lease, distribute, broadcast, sublicense, or otherwise assign any rights to the Kindle Content or any portion of it to any third party.” And even though Amazon invites you to “buy” a Kindle ebook, it’s the language of the DRM, not the button that we click, that governs the transaction: “Kindle Content is licensed, not sold, to you by the Content Provider.” [Kindle Content is what we used to call books, and content providers are what we used to call bookstores.]

Content providers are free to control their property even after we’ve downloaded it to our personal e-readers. That’s how Amazon justified secretly removing copies of George Orwell’s 1984 from readers’ Kindles when the company discovered it had been selling a bootleg edition of the work. When news of this peremptory take-back came out, though, there was a public outcry. Amazon apologized for not notifying customers in advance, but not for seizing the books — the DRM gives Amazon the right to reach into customers’ digital devices and remove company property. Moreover, in cases where it thinks that customers have violated the terms of service agreement, Amazon, like any responsible landlord, may lock them out of their account and delete the contents of their library. The DRM agreement may not say so explicitly, but it allows Amazon, Apple, or any other “content provider” to revoke your right to read.

And what about a student’s right to read? Or not to read? Enrolling in a class shouldn’t require students to surrender their privacy to the Thought Police any more than it requires them to surrender their freedom of speech at the schoolhouse gate. It’s not even clear that ebook spyware will improve student performance. It may tell instructors if their students are hitting the books, and how much time it takes them to plow through chapter seven. But that may not really correlate with success in a course. Many students insist they learn the course material not from the textbook, but from lectures and discussions, by working problem sets, or by reading SparkNotes.

Digital technology gives us access to information, to content, if you will, on a scale never before possible. But it works two ways, giving content, or content providers, access to us as well. Our keystrokes, our browsing history, our likes and dislikes, all of that becomes the property, not of the reader, but of the digital rights manager. As George Orwell put it so succinctly in 1984, “BIG BROTHER IS WATCHING YOU.”

Ebook analytics, or, the watcher watched: While you read 1984 on your digital device, 1984 reads you.

Dennis Baron is Professor of English and Linguistics at the University of Illinois. His book, A Better Pencil: Readers, Writers, and the Digital Revolution, looks at the evolution of communication technology, from pencils to pixels. You can view his previous OUPblog posts here or read more on his personal site, The Web of Language, where this article originally appeared. Until next time, keep up with Professor Baron on Twitter: @DrGrammar.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only education articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

November 23, 2012

Friday procrastination: Turkey edition

Goodbye Thanksgiving, hello Black Friday — or in my case leftovers. Any one else play Pandemic with their family?

Had a horrible Thanksgiving with the family? Carolyn Kellogg put together this great quiz on dysfunctional families of fiction.

In celebration of Bible Week, Oxford Journals created a collection of free articles on Biblical Studies.

Academic like a rockstar! (including that awful aging period)

Do you know what rights you have given up simply by reading this?

Anna Clark examines one area where translation is growing — academia.

Jennifer Howard has a helpful piece on the influence of university presses, following UP Week.

More changes to how we pay — the rise of Bitcoin.

The British Library is releasing images of its medieval manuscripts into the public domain. (And I strongly recommend following the Lost and Found Tumblr.)

Brain Pickings offers a visual timeline of the future.

I will not disclose my fear of copyeditors.

What happens to your brain in hemispatial neglect?

Douglas Fields on the danger of changes in scientific publishing.

And finally, for those of us who need a better understanding of our colleagues’ accents, Peter Sellers demonstrates:

Click here to view the embedded video.

Alice Northover joined Oxford University Press as Social Media Manager in January 2012. She is editor of the OUPblog, constant tweeter @OUPAcademic, daily Facebooker at Oxford Academic, and Google Plus updater of Oxford Academic, amongst other things. You can learn more about her bizarre habits on the blog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Marian Stamp Dawkins on why animals matter

There is an urgent argument for the need to rethink animal welfare, untinged by anthropomorphism and claims of animal consciousness, which lack firm empirical evidence and are often freighted with controversy and high emotions. With growing concern over such issues as climate change and food shortages, how we treat those animals on which we depend for survival needs to be put squarely on the public agenda. Marian Stamp Dawkins seeks to do this by offering a more complete understanding of how animals help us.

Below, you can listen to Marian Stamp Dawkins talk about the topics raised in her book Why Animals Matter: Animal consciousness, animal welfare, and human well-being. This podcast is recorded by the Oxfordshire Branch of the British Science Association who produce regular Oxford SciBar podcasts.

Listen to podcast:

[See post to listen to audio]

Marian Stamp Dawkins is Professor of Animal Behavior and Mary Snow Fellow in Biological Sciences, Somerville College, Oxford University. She is the author of Why Animals Matter: Animal consciousness, animal welfare, and human well-being; Observing Animal Behaviour: Design and analysis of quantitative data ; and the forthcoming Through Our Eyes Only?: The Search for Animal Consciousness. She was awarded the 2009 Association for the Study of Animal Behavior medal for contributions to animal behavior.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only environmental and life sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Art and human evolution

Young children take to painting, singing, dancing, storytelling, and role-playing with scarcely any explicit training. They delight in these proto-art behaviors. Grown-ups are no less avid in extending such behaviors, either as spectators or participants.

Provided we have a generous view of art, one that includes appropriate mass, popular, folk, ritual, and domestic practices as well as the esoteric professional art of specialists, we all engage routinely and often passionately with art. Consider, for example, the absorption of teenagers in popular music and the extent to which it contributes to their sense of self-identity. The same continues throughout life. We are interested in TV shows, movies, novels, music, dance, and the plastic arts. In fact, almost everyone has expert knowledge about some genres of art and a broad understanding of others. Many people participate creatively as amateurs both in high art forms and in more quotidian ones, such as potting, making clothes, adorning their environments, and so on. Moreover, the art of skilled professionals often receives sophisticated appreciation involving high levels of cognitive and emotional engagement.

In other words, nothing could be more natural than our attraction to the arts. Indeed, we might suspect that their ancient origins and the universal spread of art behaviors, along with the interest and deep satisfaction to which such behaviors give rise, indicate that they are a touchstone of our biologically-framed and culturally-inflected human nature. Note that the earliest known European cave art dates back more than 35,000 years to a time when the climate was very harsh and life must have been hard; art has been ubiquitous since then or earlier.

"Meercatze" rock carving in Libya. Photo by Luca Galuzzi (www.galuzzi.it), 2007. Creative Commons License.

But now consider these same behaviors from the perspective of the Martian anthropologist. How exotic and bizarre they must appear to be! He puzzles:

They tell or enact stories about people who have never existed and yet, knowing this, they find those stories deeply stimulating and emotionally moving. They find it intriguing to view paintings of bowls of fruit but don’t spend much time gazing at actual fruit bowls. They attach catgut to plywood, scrape it with horsehair, and enjoy the noise, though many other sounds do not appeal to them in a similar way. They amuse themselves by exaggerating their normal form of locomotion by swaying, jumping, spinning, and weaving patterns in groups.

Our sporting practices and spiritual rituals would be similarly perplexing to the alien visitor.

Those of us who share some of the Martian’s amazement are bound to wonder how the arts became so important to us. They permeate our lives and consume our energies, resources, and time. Of course they are often a source of pleasure. (Though recall that we are frequently drawn to tragic dramas and to stories and music that are sad; also that much art is of unrewardingly poor quality.) Yet we may wonder just why they are enjoyed.

One possibility is that art served humans’ evolutionary agendas for reproductive success, because evolution often gets creatures to do what is in their genes’ interests by making the pertinent activities intrinsically pleasurable. Art behaviors might have been directly adaptive; their adoption was responsible for increased reproductive success and the relevant propensities were passed to future generations. For instance, art might have bonded individuals and sustained their values in ways that benefitted their reproductive chances compared to those of art-impoverished people. Alternatively, art behaviors might have been incidental by-products of other adaptive capacities, such as intelligence, curiosity, and creativity. Many such theories have been advanced and there is considerable disagreement about what the arts are alleged to have been adaptations for or about the adaptations to which they are alleged to have stood as by-products. The comparative evaluation of these various, often conflicting, positions is challenging but well deserving of close attention.

And when that is done, it remains to consider if the arts serve similar or related evolutionary functions in our modern context. Perhaps as by-products they went on later to become adaptive in some new way. Perhaps as adaptations their evolutionary advantages came to be negated by changes in the human social and physical environment.

We can say at least this much: even if art behaviors are near-universal when taken together, they are so complex and varied that each individual person expresses them in a subtly distinctive fashion. Some people love novels, others are mainly interested in movies, a person who is insensitive to poetry might be a fine dancer, etc. We can also observe that, unlike other universal behaviors that are mastered relatively cheaply, such as bipedalism, art behaviors involve significant costs and ongoing commitments. These two facts together suggest that these behaviors can serve as informationally rich signals about fitness-relevant characteristics of those who display them. That is sufficient to show an important link between art and evolution.

Stephen Davies is a Professor of Philosophy at the University of Auckland. He is the author of The Artful Species: Aesthetics, Art, and Evolution (Oxford University Press, 2012) and he blogs at artfulspecies.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only art and architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

or the OUP ANZ website.

or the OUP ANZ website.

Is spirituality a passing trend?

By Philip Sheldrake

“Spirituality” is a word that defines our era. The fascination with spirituality is a striking aspect of our contemporary times and stands in stark contrast to the decline in traditional religious belonging in the West. Although the word “spirituality” has Christian origins it has now moved well beyond these – indeed beyond religion itself.

What exactly is spirituality? Unfortunately it’s not easy to offer a simple definition because the word is now widely used in contexts ranging from the major religions to the social sciences, psychology, the arts and the professional worlds of, for example, healthcare, education, social work and business studies. Spirituality takes on the shape and priorities of these different contexts.

However, in broad terms “spirituality” stands for lifestyles and practices that embody a vision of how the human spirit can achieve its full potential. In other words, spirituality embraces an aspirational approach to the meaning and conduct of life – we are driven by goals beyond purely material success or physical satisfaction. Nowadays, spirituality is not the preserve of spiritual elites, for example in monasteries, but is presumed to be native to everyone. It is individually-tailored, democratic and eclectic, and offers an alternative source of inner-directed, personal authority in response to a decline of trust in conventional social or religious leaderships.

However, in broad terms “spirituality” stands for lifestyles and practices that embody a vision of how the human spirit can achieve its full potential. In other words, spirituality embraces an aspirational approach to the meaning and conduct of life – we are driven by goals beyond purely material success or physical satisfaction. Nowadays, spirituality is not the preserve of spiritual elites, for example in monasteries, but is presumed to be native to everyone. It is individually-tailored, democratic and eclectic, and offers an alternative source of inner-directed, personal authority in response to a decline of trust in conventional social or religious leaderships.

If we explore the wide range of current books on spirituality or browse the Web we will regularly find that spirituality involves a search for “meaning” – the purpose of life. It also concerns what is “holistic” – that is, an integrating factor, “life seen as a whole”. Spirituality is also understood to be engaged with a quest for “the sacred” – whether God, the numinous, the boundless mysteries of the universe or our own human depths. The word is also regularly linked to “thriving” – what it means to thrive and how we are enabled to thrive. Contemporary approaches also relate spirituality to a self-reflective existence in place of an unexamined life.

How is spirituality to be supported? The great wisdom traditions suggest the adoption of certain spiritual practices and it is this aspect of spirituality that attracts many contemporary people. Forms of meditation, physical posture or movement such as yoga, disciplines of frugality and abstinence (for example from alcohol or meat) or visits to sacred sites and pilgrimage (for example the popular practice of walking the “camino” to Santiago de Compostela) are among the most common. The point is that spiritual practices are not merely productive in a narrow sense but are disciplined and creative. A commitment to the regularity of a spiritual discipline like meditation gives shape to what may otherwise be a fragmented life. Many people also experience their creative activities in art, music, writing and so on as spiritual practices. Classic practices are all directed at spiritual development. Thus, meditation may cultivate stillness or attentiveness but the great religious traditions such as Buddhism or Christianity also relate such practices to personal transformation – whether in terms of personal ethics or increased social responsibility. Over time meditation may facilitate a growing freedom from destructive energies that inhibit healthy relationships. Such a growth in inner freedom makes us more available and effective as compassionate presences in the world.

meditation, physical posture or movement such as yoga, disciplines of frugality and abstinence (for example from alcohol or meat) or visits to sacred sites and pilgrimage (for example the popular practice of walking the “camino” to Santiago de Compostela) are among the most common. The point is that spiritual practices are not merely productive in a narrow sense but are disciplined and creative. A commitment to the regularity of a spiritual discipline like meditation gives shape to what may otherwise be a fragmented life. Many people also experience their creative activities in art, music, writing and so on as spiritual practices. Classic practices are all directed at spiritual development. Thus, meditation may cultivate stillness or attentiveness but the great religious traditions such as Buddhism or Christianity also relate such practices to personal transformation – whether in terms of personal ethics or increased social responsibility. Over time meditation may facilitate a growing freedom from destructive energies that inhibit healthy relationships. Such a growth in inner freedom makes us more available and effective as compassionate presences in the world.

It follows from this that, as the great traditions emphasise, spirituality is actually concerned with cultivating a “spiritual life” rather than simply with undertaking practices isolated from commitment. It offers a “value-added” factor to personal and professional lives. So, for example, in a variety of social contexts spirituality is believed to add two vital things. First, it saves us from being purely results-orientated. Thus, in health care it offers more than a medicalised, cure-focused model and in education it suggests that a holistic approach to intellectual, moral and social development is as vital as acquiring employable skills. Second, spirituality expands ethical behaviour by moving it beyond right or wrong actions to a question of identity – we are to be ethical people rather than simply to “do” ethical things. Character formation and the cultivation of virtue then become central concerns.

Finally, is spirituality simply a passing trend? Current evidence suggests a growing diversity of new forms of spirituality as well as creative reinventions of the great traditions. The language of spirituality continues to expand into ever more professional and social worlds – for example urban planning and architecture, the corporate world, sport and law. Most strikingly there are recent signs of its emergence in two contexts that have been especially open to public criticism – commerce and politics. Equally, the Internet is increasingly used to expand access to spiritual wisdom. So, on current evidence, spirituality appears to be less of a fad than an instinctive desire to find a deeper level of values to live by. As such, it seems likely not only to survive but to develop further into many new forms.

Professor Philip Sheldrake is currently Senior Research Fellow in the Cambridge Theological Federation (Westcott House), Honorary Professor of the University of Wales, and a regular visiting professor in the United States. He is also a member of the Guerrand-Hermès Forum for the Interreligious Study of Spirituality. For over twenty-five years he has been a leader in the field of spirituality as an interdisciplinary area of study. He is author of a dozen books, including Spirituality: A Very Short Introduction (OUP, November 2012).

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday!

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more on this book on the

Image credits: Yoga session at sunrise in Joshua Tree National Park – Warrior I pose. Photo by Jarek Tuszynski, 2008. Creative Commons License. (via Wikimedia Commons); Buddhist monks meditating on Vulture Peak. Photo by unknown Wikimedia Commons user. Creative Commons License. (via Wikimedia Commons).

November 22, 2012

Words we’re thankful for

A version of this article originally appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Here on the OxfordWords blog we’re constantly awed and impressed by the breadth and depth of the English language. As this is a great week to be appreciative, we’ve asked some fellow language-lovers which word they’re most thankful for. From quark to quotidian, ych a fi to robot, here’s what they said:

Thanksgiving postcard. NYPL Digital Collection.

stillicide

Of incredible value to the crime writer or anybody else wishing to build suspense into a landscape, stillicide is the falling of water, especially in drops, or a succession of drops. Inexplicably underused — every day brings a new way to employ it.

- Zadie Smith, author*

quark

We should obviously be thankful for quarks, without them the universe would be a dull place, but we should also be grateful for the word, quark, which has a playfulness and far-reaching allusion not always found in scientific coinages.

When Murray Gell-Mann came up with a new model for understanding sub-atomic particles he needed a new word to describe his new little tiny things. He liked the sound of kwork (to rhyme with fork) so that’s what he called them, he was just a bit unsure about the spelling. While pondering the issue he picked up Finnegans Wake and came upon this:

Three quarks for Muster Mark! Sure he hasn’t got much of a bark And sure any he has it’s all beside the mark.

Joyce’s word jumped out at Gell-Mann and gave him his spelling. He used it when he reported his ideas in the journal Physics Letters (1 Feb. 1964) and gave as his source, in a footnote, Finnegan’s Wake. (Not Finnegans Wake, you’ll notice: even Nobel winning professors sometimes get their apostrophes wrong.)

Most people now pronounce the name of Murray’s particle to rhyme with bark and mark, the same way they pronounce the German cheese. Quark, the low-fat curd, is unrelated etymologically to quark, the subatomic particle, but it may have contributed to ongoing confusion about whether or not the world is made of cheese.

- Robert Hughes, Science Researcher, Oxford English Dictionary

English

How about ENGLISH — because by implication you could argue it includes all the others?

- Inge Milfull, Senior Assistant Editor, Oxford English Dictionary

feckless, effete

A totally great adjective. One reason that the slippage in the meaning of effete is OK is that we can use feckless to express what effete used to mean (‘depleted of vitality, washed out, exhausted’). Feckless primarily means ‘deficient in efficacy, lacking vigor or determination, feeble’; but it can also mean ‘careless, profligate, irresponsible.’ The word appears most often now in connection with wastoid youths, bloated bureaucracies — anyone who’s culpable for his own haplessness. The great thing about using feckless is that it lets you be extremely dismissive and mean without sounding mean; you just sound witty and classy. The word’s also fun to use because of the soft-e assonance and the k sound—and the triply assonant noun form — fecklessness – is even more fun.

- David Foster Wallace, author and lecturer *

moider and mither

May I have two — they’re hard to unpick. I’m thankful for the verbs moider and mither. My mother was first gen. Irish brought up in Lancashire and used moider (moither) and mither interchangeably to mean anything from ‘being befuddled’ to ‘being pestered’ (usually by us). Maybe that’s why it often sounded more like murder than mither, although that could just be the accent. From a young age, both these verbs got muddled further in my mind with the word mother so that now whenever I hear anyone use either verb I think of my mother — in the nicest way possible of course.

- Barbara Whitfield, Research Assistant, Oxford English Dictionary

challenge

I’m thankful for the word challenge because I find it a useful substitute for a variety of more negative words: problem, difficulty, obstacle, issue, hassle, bother… A challenge implies a test; it implies that it’s something I can meet, something that I can rise to. Using it helps me to think positively: I can win. Challenge? Accepted.

- Malie Lalor, Senior Marketing Manager, Oxford Dictionaries

handless

I love the word handless (or haunless) in the sense ‘clumsy/incompetent with one’s hands/unable to do simple tasks’, which has been used in English since the 15th c. but is now mainly restricted to Scottish and Irish English — a loss to the rest of the English-speaking world, I think! The sense ‘clumsy’ can be expressed by other words — many, naturally, relating to hands, such as butter-fingered and ham-fisted. The sense ‘unable to do simple tasks’, however, — in, for example, ‘He’s that handless he can’t even make a cup of tea’ or ‘Where are the beans? Find them yourself, you handless idiot’ — doesn’t have any exact equivalents. There’s unhandy but, as the direct antonym of handy, it’s mainly used of people who can’t do manual tasks like putting up shelves. And there are loose synonyms like inept, incompetent, and useless, but these are more general and don’t have quite the same scornful, rolling-your-eyes-in-frustration tone to them as handless.

- Kate Wild, Assistant Editor, Oxford English Dictionary

Click here to view the embedded video.

bleary

There is in the English language no better word for talking about hangovers.

- David Auburn, playwright *

Words containing the letters ‘umb’

Ever since I found in my childhood paintbox a small square of reddish-brown watercolor pigment labeled burnt umber, I have been enchanted with the wonderfully euphonious catalog of words that revolve around the letters umb, and which generally have something to do with the Latin for shadow. To be sure, cucumber (like its ancestor cowcumber, a form which we are haughtily informed no well-taught person still uses) has no connection, and the verb cumber, meaning ‘to hinder,’ has only the most tenuous link, via an Old French term connected to cumulus, which defines a cloud that, among other attributes, spreads an unusually large and dark shadow below it. In my shadowland of fine-sounding words we find umbrella, penumbra, sombrero, somber, the Italian province of Umbria – the land of shadows — and here, adumbrate, which sounds more euphonious than all the rest, and in my view should be used as often as possible whenever you want to sketch or outline or otherwise prefigure or, of course, foreshadow something. When the edge of a thundercloud passes across the sun and you look up and draw your sweater around your shoulder and shudder — the chill you feel at that moment nicely adumbrates the storm to come.

- Simon Winchester, author, journalist and broadcaster *

quotidian

A non-ordinary word to describe ordinariness: it refers to the daily, the mundane, the well-known. Your commute becomes a little more interesting if it is described as “quotidian” instead of “daily.”

- Alexandra Horowitz, author *

conjunctions, nevertheless

My favourite class of word is the conjunction, since with a conjunction a sentence need never be finished. In addition, anything that anyone else says can be contradicted. However I am most thankful most for the adverb nevertheless, since with this powerful word, talk and argument can go on for ever, with no closure and resolution. It is a cleverly constructed word, with a stress pattern that seems to empathize the repeated hoof-beats of those repeated ɛ sounds. Nevertheless, by tomorrow I may have changed my mind.

- Giles Goodland, Senior Editorial Researcher, Oxford English Dictionary

quirky

I have always thought of quirky to be the opposite of normal. To me, quirky has a whimsical, adventurous, daring, fearless quality about it. It doesn’t care what other people think, quirky just does its own thing and is all the more interesting for it.

- Julia Callaway, Marketing Assistant, Oxford Dictionaries

owsell

Shortly before the end of my schooldays I joined a book club for the sole reason that the introductory offer allowed me to buy the Compact OED – the photographically reduced version of the first edition which many of you will be familiar with — for some ridiculously low price. Of course, when my purchase arrived, I had great fun browsing its pages; and I distinctly remember that during one such browsing session I came across the entry for the word owsell. It was a short entry, with just a single illustrative quotation, and the eye might easily pass over it (especially when scanning those pages of extremely small print without using the magnifying glass that came with the edition — something I don’t suppose I could do so easily nowadays!); but it caught my eye. And all it said was: ‘Etymology and sense obscure.’ It took a moment for the significance of this to sink in, but yes: here was a word that the Dictionary’s editors had decided to include even though they didn’t know what it meant. Wow, I thought. This is some dictionary.

To be honest I didn’t really know much about the OED at the time, but discovering that it included words like owsell — and it’s by no means the only word included whose meaning is unknown — increased my respect for it considerably. It was certainly a vivid illustration of the kind of comprehensiveness that the Dictionary aimed at. And it was through serendipitous discoveries like these that my Compact OED fed my fascination with words… and, in a small way, contributed to my becoming a lexicographer. It’s certainly a word to be thankful for.

Its meaning, by the way, is still unknown. OED Online provides a revised entry for owsell has been revised, but although the etymology is longer, it does no more than point out that the word ouzel (a kind of bird), while occasionally taking the spelling owsell in the early modern period, can’t really be made to fit the one quotation we have. Which, by the way, is from the obscure book A Sixe-folde Politician (1609) by the almost equally obscure writer Sir John Melton, and which reads as follows: ‘Neither the touch of conscience, nor the sense..of any religion, euer drewe these into that damnable and vntwineable traine and owsell of perdition.’ If you know what it means, do let us know.

- Peter Gilliver, Associate Editor, Oxford English Dictionary

phantasmagoria

Not for any real reason other than it sounds exactly as it should. Especially for a word that originates from an exhibition of optical illusions and means ‘a sequence of real or imaginary images like that seen in a dream’.

- Hannah Wright, Marketing Executive, Oxford Dictionaries

Appendix: ‘On the word robot’

By Karel Čapek

A reference by Professor Chudoba to the Oxford Dictionary’s account of how the word robot and its derivatives caught on in English reminded me about an old debt. For the author of the play RUR didn’t think up the word, he merely brought it to life.

This is it how it happened: in an unguarded moment the author in question was struck by the idea for the play. He rushed with it still fresh in his mind straight to his brother Josef, the painter, who was standing at his easel, painting away, brush bustling over the canvas.

‘Hey, Josef,’ began the author, ‘I might have an idea for a play.’

‘What sort?’ mumbled the painter (he really did mumble, because he had a paintbrush in his mouth).

The author told him as briefly as he could.

‘Well, write it, then,’ said the painter, without even taking the brush out of his mouth or pausing over his canvas. It was indifference to the point of insult.

‘The thing is,’ said the author, ‘I don’t know what to call the artificial workers. I could call them laboriers, but that just sounds a bit wooden.’

‘Call them robots, then,’ mumbled the artist with the paintbrush in his mouth, still painting away.

And that was it. That’s how the word robot was born; may it hereby be attributed to its real creator.

[NB. Professor F. Chudoba (1878–1941), mentioned in the opening line, was a Czech scholar of English Literature.]

(From the newspaper Lidové noviny, 24 December 1933)

Čapek’s article available in Czech. robot

The word robot is such a well-established part of our language and popular culture, it’s incredible to think that if it hadn’t been for one Czech cubist painter, it might never have existed at all.

Robot, in the sense of ‘android’, was first used by the Czech writer Karel Čapek (1890-1938) in his 1920 play RUR: Rossum’s Universal Robots.

Thanks to the success of the play, which was immediately translated from Czech into dozens of languages, the word robot was soon being used by writers all over the world.

But as Čapek himself acknowledged in an article written many years later (translated to the left), the word robot wasn’t actually his invention. It had been coined, almost accidentally, by his brother, the writer and artist Josef Čapek (1887-1945).

The word robot comes from the Czech word robota, meaning ‘forced labour’ or (by extension) ‘drudgery’. Karel Čapek’s original name for the mass-produced workers in his play was laboři (singular laboř), from the classical Latin labor. This was a new coinage in Czech (unlike ‘labourer’ in English) and there is no neat way of translating it — laborier, laboror, labroron, or even laborian.

None of these words has the same ring to it as robot: it’s hard to imagine anyone going to see a play called Rossum’s Universal Laborons. Would Asimov ever have written I, Laborier? And what kind of Hollywood mogul would have backed the movie LaboroCop?

As Čapek’s play suggests, the day may come when robots turn against their masters and humanity breathes its last. But in the meantime, let’s give thanks for the word robot — and for the genius of the Čapek brothers.

- Patrick Phillips, Assistant Editor, Oxford English Dictionary

How about you? Which word are you most thankful for? Share it with us in the comments below.

If you’re feeling inspired by the words featured in today’s blog post, why not take some time to explore OED Online? Most UK public libraries offer free access to OED Online from your home computer using just your library card number. If you are in the US, why not give the gift of language to a loved-one this holiday season? We’re offering a 20% discount on all new gift subscriptions to the OED to all customers residing in the Americas.

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) is widely regarded as the accepted authority on the English language. It is an unsurpassed guide to the meaning, history, and pronunciation of 600,000 words— past and present—from across the English-speaking world. As a historical dictionary, the OED is very different from those of current English, in which the focus is on present-day meanings. You’ll still find these in the OED, but you’ll also find the history of individual words, and of the language—traced through 3 million quotations, from classic literature and specialist periodicals to films scripts and cookery books. The OED started life more than 150 years ago. Today, the dictionary is in the process of its first major revision. Updates revise and extend the OED at regular intervals, each time subtly adjusting our image of the English language.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language, lexicography, word, etymology, and dictionary articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OxfordWords blog via RSS.

* Starred excerpts taken with permission from the Oxford American Writer’s Thesaurus.

Meditation experiences in Buddhism and Catholicism

Becoming a Tibetan Buddhist nun is not a typical life choice for a child of an Italian Catholic police officer from Brooklyn, New York. Nevertheless, in February of 1988 I knelt in front of the Dalai Lama in Dharamsala, India, as he cut a few locks of my hair (the rest had already been shaved), symbolizing my renunciation of lay life.

I lived in the vows of a Buddhist nun for a year, in the course of spending two years living in Buddhist monasteries in Nepal and India. Including my years of lay practice, I spent twenty years of my adult life practicing Buddhism, before returning to the Catholicism into which I had been born and baptized.

During my years as a Buddhist, I was exposed to many ways of meditating. They were all new to me, as my prayer as a young Catholic was largely limited to recitation of rote prayers and did not include any sort of contemplative practice.

Following my return to Catholicism, images and ideas from my Buddhist experiences arose spontaneously in my prayer. During one early retreat, I recorded in my journal an experience of sitting under a tree “imagining Thousand-Armed Chenrezig [the Buddha of Compassion] with enough hands to help in all directions.” I saw Chenrezig as “one way of imaging Christ — in all places, with hands to help wherever necessary.”

Following my return to Catholicism, images and ideas from my Buddhist experiences arose spontaneously in my prayer. During one early retreat, I recorded in my journal an experience of sitting under a tree “imagining Thousand-Armed Chenrezig [the Buddha of Compassion] with enough hands to help in all directions.” I saw Chenrezig as “one way of imaging Christ — in all places, with hands to help wherever necessary.”

That experience and others like it sparked in me an interest in exploring how prayer forms from one religious tradition might be adapted for use in other traditions. Over the years, I have found that much of what I learned about and experienced of Buddhist meditation during those years enriches my prayer life as a Christian. Many of the “analytical” meditations, which I learned when I lived in Tibetan Buddhist communities in Nepal and India and continued to practice after my return to the United States, have particularly enhanced my religious experiences.

In the years since my return to Catholicism, I have come to learn that, like my decision to become a Buddhist nun, my comfort with incorporating prayer practices from one faith tradition into another is not the norm, and that what has seemed so natural to me is not natural for everyone. Many people have a fear of other religions and a nervousness about incorporating any elements drawn from other faith traditions into their own religious practice.

Pope Benedict XVI (while he was still Cardinal Ratzinger) wrote in his “Letter to the Bishops of the Catholic Church on Some Aspects of Christian Meditation” in 1989 that prayer and meditation practices from other religions should not be “rejected out of hand simply because they are not Christian. On the contrary, one can take from them what is useful so long as the Christian conception of prayer, its logic and requirements are never obscured.”

Christians in many parts of the world have long looked to Buddhism and other Eastern religions for spiritual nourishment. While some of those have abandoned their Christianity altogether (as I did for many years) many other have already incorporated Zen meditation or Theravadan vipassana meditation into their Christian prayer.

Prayer is essential if we are to grow spiritually. We cannot grow in our relationship with God unless we take time to nurture that relationship through prayer. And we cannot grow in our love of others — the love that isn’t based on affection, but the universal love that includes loving our enemies — without the grace that comes from prayer. So I care a lot more that people pray than how they pray. Nonetheless, we can all benefit from learning to pray in new ways.

Susan J. Stabile is the author of Growing in Love and Wisdom: Tibetan Buddhist Sources for Christian Mediation, just published by Oxford University Press. A spiritual director and retreat leader, she is also the Robert and Marion Short Distinguished Chair in Law at the University of St. Thomas School of Law.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credit: A yound woman clasps her hands in prayer. Photo by justinkendra, iStockphoto.

Music we’re thankful for

Thanksgiving is upon us in the US. Before the OUP Music team headed home for some turkey and stuffing, we compiled a list of what we are most thankful for, musically speaking. Read on for our thoughts, and leave your own in the comments. Happy Thanksgiving!

“I am thankful for my primary school teacher’s unshakeable belief that everyone has some musical ability. She encouraged everyone to sing or play an instrument, and if you showed any inclination to continue you knew you had her full support. Music was fun, and I don’t think it crossed our minds to question whether were any good at it or not: we just assumed we all were because she told us so! I’m thankful to Mrs. Jones for instilling that self-belief into my 6-year old self.”

—Anwen Greenaway, Promotion Manager (New Music), Sheet Music

“Recently, every time I sit down at the organ to play my Sunday postlude (usually a selection from J.S. Bach’s Orgelbüchlein), I’m so thankful that I have an instrument to practice and perform on, which is something I did not have for the first four of my eight years and counting in New York City. Playing organ music, especially organ music written by Bach, activates parts of my brain that otherwise remain pretty dormant, and the physicality of playing the instrument is intensely satisfying for me. Thankful for the training I received to play this instrument, thankful for having an instrument at my disposal!”

—Meg Wilhoite, Assistant Editor, Grove Music Online/Oxford Music Online

“Now that the Internet has come to dominate music, it’s much more difficult for people to find a single artist as a touchpoint. Your friend goes nuts to American hard-core as you silently appreciate shoe-gaze. Artists that dominate the music market are often defined more by love and hate than by a unified opinion. You love Lady Gaga and hate Justin Bieber, or vice versa. Arguments about the merits of either artist are likely to lead to no friends, so common ground must be found only in the opinion of meat dresses and hair styles. So when “Gangnam Style” became a viral video hit, I expected the same divisional arguments. But something odd happened – everyone liked it. In a language most listeners don’t understand, Psy satirizes overly-stylized pop videos and the culture of an affluent Seoul neighborhood, and presents one of the goofiest dances known to mankind. The song and video are fun and making fun of themselves at the same time. Endless parodies and imitations appeared. Gang wars broke out over the dance. And you can’t hate it.”

—Alice Northover, Social Media Manager

Click here to view the embedded video.

“I’m thankful for my parents encouraging me to start taking piano lessons (and talking me out of quitting) when I was five. Playing piano — and music in general — ended up playing a major role in my life growing up and enabled me to make a lot of great friends through the groups I accompanied. While my piano is still at my parents’ house in Pennsylvania, I look forward to the day when I have an apartment big enough to move it in with me!”

—Alyssa Bender, Marketing Assistant, Academic/Trade

“I am thankful for the many great dance venues in New York City — from Lincoln Center, to the Joyce Theater, to Dance New Amsterdam, to the Brooklyn Academy of Music, just to name a few — and the staff and especially the volunteers who make it possible to see fantastic performances in each of these places. If you are planning to visit New York City this winter, or if you live here and enjoy dance, will you let me know what you plan to see?” (Email Norm at norman[dot]hirschy[at]oup[dot]com)

—Norm Hirschy, Editor, Music and Dance

“It recently dawned on me just how grateful I am for the music of Benjamin Britten. Fortunately for me, Britten’s birthday falls on Thanksgiving this year, so I have the perfect excuse for publically expressing my gratitude. I was lucky enough to sing his music when I was a kid—I have particular fondness for the song “Cuckoo!”, which Britten wrote in the 1930s and was recently featured, with several other of his works, in Wes Anderson’s film Moonrise Kingdom. It was little pieces like that that showed me how magical songs could be, however simple they appeared, and I have been dedicated to Britten’s music ever since. I’ve also found that several other artists I admire were also exposed to his music at a young age, and discovering the incorporation of Britten’s music into the works of Anderson and Jeff Buckley was thrilling.”

—Jessica Barbour, Associate Editor, Reference, Oxford Music Online/Grove Music Online

Click here to view the embedded video.

“I am thankful for music, which has surrounded, consoled and inspired me since before I can remember.”

—Carol Barnett, composer of Angelus ad virginum and ‘Shepherds, rejoice!’ in An American Christmas

“I’m thankful to my Gran for introducing me to ballet dancing and for taking me to see so many Tchaikovsky ballets as a child. It was the love she instilled in me for Swan Lake and The Nutcracker that encouraged me to take an interest in classical music. Without her, I might never have learnt the flute, studied music at university, or started working in the OUP music department!”

—Emma Shires, Editorial Assistant, Sheet Music

“I am thankful for the music of Tchaikovsky, in particular The Nutcracker Suite. Even though my dreams of becoming a ballerina are over, whenever I hear his beautiful Ballet Suites I am reminded of that little girl in her tutu and her sheer excitement of being taken to see The Nutcracker at the age of four (that little girl was me, once upon a time).”

—Ruth Fielder, Sales Administrator, Sheet Music

Click here to view the embedded video.

“I’m thankful my 11-year-old son still lets me play guitar with him, even though I’m now relegated to back-up.”

—Anna-Lise Santella, Editor, Grove Music/Oxford Music Online

“I’m thankful for my neighbours who don’t seem to mind the noise that comes from my flat when I’m practising. I can imagine that living above or next to musicians can be awful, but they are always pleasant and have never complained, making my life a lot easier!”

—Lucy Allen, Print & Web Marketing Assistant, Sheet Music

“This Thanksgiving season, I am especially thankful for my piano teacher Mrs. James K. Bence for providing me the opportunity to take piano lessons as a child. You see, Mrs. Bence was white and I am black — living on different sides of the track. In small town Alabama, USA, during the late 1960s and 1970s, it was still culturally unacceptable in the minds of many southerners for blacks and whites to share life experiences. But every Saturday, I was welcomed into Mrs. Bence’s home for my piano lessons. I didn’t find out until I was an adult the difficulties and harassment Mrs. Bence experienced from her neighbors because she gave lessons to me and other black children. Mrs. Bence was a tender but brave-hearted woman. She’s gone now but a part of her lives in every song I compose.”

—Rosephanye Powell, Co-editor of Spirituals for Upper Voices

“My life and career seem to be continually in a state of learning and growing. This is thanks to the examples shown and benchmarks set for me by many significant mentors in my life. I’m happy to thank them! Roger Wischmeier was not only an organ teacher but also a complete church musician who taught me accompanying, hymn playing, choir directing from the organ, and the priority of text. Eleanor Murray taught me that keyboard improvisation was most effective when it was as musically compelling as the spirit within the soul of the words. Alexander Fiorillo, my piano teacher, valued my expressivity but did not allow me to get by with that at the expense of accurate technique. He also knew exactly how far to push me before I lost my spirit! Robert Page is still my finest example that cross-over repertoire of all kinds should be prepared and performed at the highest level of performance practice and enthusiasm, thus blending musical integrity with stylistic diversity. Dale Warland is the benchmark for pristine and exacting choral preparation while exploring the cutting edge of new repertoire and the interaction between artist, performer, and audience. Finally, Wesley Balk gave insight and specific curriculum to blending the technique and artistry of the Complete Singer/Actor into an amazing complete performer! I continue to learn from and am grateful for these mentors’ gifts to me and hope to pass them on to those with whom I interact.”

—Jerry Rubino, choral director/arranger/pianist and editor of OUP’s A Merry Little Christmas and An American Christmas

“I will always be thankful for opportunities I was given as a member of my county youth orchestra. I started playing the violin in the string training orchestra when I was 11, moving on to the full symphony orchestra of c. 100 players at 13. In this orchestra I discovered the most amazing music, including symphonies by Mahler, Elgar, Walton, Beethoven, Rachmaninoff, and Shostakovich. We also visited some incredible places, with tours to South Africa and Chile. Perhaps most of all, though, I’m grateful to have been introduced to like-minded people, many of whom are still great friends today. I even met my husband in the orchestra!”

—Robyn Elton, Senior Editor/Music Department

“I never thought I would admit to this, but I am thankful for my sister’s incessant singing. Growing up, recitals and other various performances were always big family outings, and until I was old enough to stay home by myself, I was forced into a party dress, shoved in the minivan, and instructed to sit still and be quiet while my sister took the stage. To this day, I have the entire Christmas program of her singing group, the Colorado Children’s Chorale, memorized (I think I may remember more lyrics than she does). Fifteen years later not much has changed, except for my appreciation. My parents are still first in line to attend any and all performances, but now they make the trek from their home in Denver to my sister’s new home in Baltimore. I hop on the bus from New York City and meet them at the theater, thankful that we can still do these things together just as we used to, even though we live so far apart.”

—Victoria Davis, Marketing Coordinator, Online Reference

What are you thankful for? Leave your thoughts in the comments. And in the meantime, check out our Spotify playlist of Thanksgiving-themed music!

Alyssa Bender joined Oxford University Press as a marketing assistant in July 2011. She works on academic/trade history, literature, and music titles, and tweets @OUPMusic. Read her previous blog posts.

Oxford Reference is the home of Oxford’s quality reference publishing, bringing together over 2 million entries, many of which are illustrated, into a single cross-searchable resource. Newly relaunched with a brand new look and feel, and specifically designed to meet the needs and expectations of reference users, Oxford Reference provides quality, up-to-date reference content at the click of a button. Made up of two main collections, both fully integrated and cross-searchable, Oxford Reference couples Oxford’s trusted A-Z reference material with an intuitive design to deliver a discoverable, up-to-date, and expanding reference resource.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Spitting blood: the absence and presence of tuberculosis

Flying back from Boston recently I was delighted to be able to watch the 2008 film version of Frost and Nixon. I had greatly enjoyed the play in London and heard the film was also very good. So I plugged in the headphones and settled back.

Before too long ex-president Richard Nixon is telling would-be interviewer David Frost how he bonded with his Russian counterpart Nikita Khrushchev over their shared sadnesses: Nixon had lost two brothers to tuberculosis. There it was again, the passing reference to this disease, which until the 1980s we thought the developed world had left behind.

It’s been a familiar experience for me while I have been writing Spitting Blood. In completely unconnected biographies I would read about this sibling, child, parent, cousin, aunt, uncle or friend who suffered and died. When people asked me what I was working on, a common response to “a history of tuberculosis” was to tell me about who in their family or circle of close friends had died or at least had the disease. My brother-in law Louis was rendered motherless when she died on the operating table undergoing chest surgery, a final desperate measure to alleviate an otherwise gloomy prognosis. It was said in the family that she had fallen ill, dancing under the stars at a rooftop nightclub in Houston Texas, catching the “cold” that became tuberculosis. And then my respondents also often asked rather nervously, “Isn’t it coming back?”

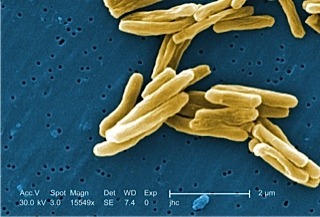

Magnified nearly 16,000 times, the rod shaped Mycobacterium tuberculosis as seen with a scanning electron microscope.

Now before you jump in, I do know about ‘salience’ and that if I had been working on the history of a cancer or depression, the shared experiences of these diseases would have abounded, but these are very much of the here and now as well as the past. A quick Internet search will reveal lots of self-help advice for those two conditions, but not much for tuberculosis. Yet it was the switch from the past to the present, the wondering about why memories of this once common, debilitating, and deadly disease should be troubling their consciousnesses now, that seemed to unsettle.

Because yes, tuberculosis is back. Perhaps, more accurately, it never went away. In Britain, although the great epidemic of the early industrial period had long passed and the breezy sanatoria finally closed their windows and doors after the new wonder drugs of the post-WWII mopped up the final cases, there was also a residuum of illness. It lurked (and lurks) where poverty and deprivation made their homes and often overlapped with areas of intense immigration from the less well off parts of the world.

Here the disease had most certainly never gone away. It was largely ignored in the classic era of tropical medicine and empire. Then the focus was on the exotic diseases often caused by parasites and spread by insects such as malaria and sleeping sickness and the acute crowd diseases of plague and cholera. These infectious diseases could play havoc with international trade if quarantine had to be enacted. Indeed tuberculosis was thought to be a disease of civilisation that the populations of the tropics would not suffer from, still being in that innocent pre-industrial state. When people began to look for it, there was plenty of tuberculosis to be found.

After WWII, in the new era of the World Health Organisation (WHO), tuberculosis was an early priority. There were now potent antibiotics, new diagnostic technologies in the form of mass miniature X-rays, and a political will.

Click here to view the embedded video.

While the Scandinavian countries spearheaded BCG vaccination at the national level, the WHO encouraged all its member states to anti-tuberculosis programmes.

So what went wrong? What caused the recurrence of tuberculosis in the west in the 1980s and fuelled the disease’s continued devastation in middle and especially low-income countries around the world? Why are we now faced with bacteria that are resistant to the available drugs? This situation worries those leading the global fight against the disease, who fear that the gains of recent years will be lost once more.

A recent case I came across involved a friend of a friend who had happily recovered from tuberculosis; the doctors thought she had caught it while riding on the Paris Metro in the 1990s. It’s amazing how many of us have personal connections to tuberculosis today. Who do you know?

Helen Bynum is a freelance historian and author of Spitting Blood: The history of tuberculosis.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credit: Mycobacterium tuberculosis; in public domain, via CDC / Dr. Ray Butler.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers