Oxford University Press's Blog, page 1005

November 14, 2012

Six WOTY confusables about GIF

There has been some widespread confusion on a few things relating to GIF’s selection as Word of the Year [USA], so we thought it would be helpful to give a little roundup for clarification.

(1) Oxford Dictionaries USA and The New Oxford American Dictionary (and Oxford Dictionaries UK and Oxford Dictionary of English) are not the Oxford English Dictionary. OUP publishes many dictionaries and the OED is only one of them.

(2) GIF (verb) is word of the year. We’re well aware that the acronym GIF has existed since 1987; it is the evolution of the acronym into a verb that we find lexically interesting. The language has evolved with the use of the GIF. (Additionally, Word of the Year doesn’t have to be a new word; it just has to exemplify the year. Higgs Boson and Super Pac are decades old, and they were both on our shortlist this year.)

(3) Oxford Dictionaries defines word as “a single distinct meaningful element of speech or writing, used with others (or sometimes alone) to form a sentence and typically shown with a space on either side when written or printed.” GIF, whether used as a noun in the traditional way or in the novel use as a verb that we have showcased in our Word of the Year choice, fits this definition. Many common words, such as radar and AIDS, are acronyms. The Word of the Year is a light-hearted effort by our lexicography team to showcase developments in the English lexicon. Words chosen will only be entered into our dictionaries if they meet our standards of evidence.

(4) People began using GIF as a verb this year. It is still a relatively new usage, so you may not have heard it. We offered a few selections in our previous pieces and a few web searches will show you how people are using the language (for example, the Tumblr hashtags gifed or giffing). Is it such an illogical step? Consider when you stopped searching things on Google and started Googling.

A worthy example (and cause):

(5) GIFs may have roles beyond snark. They’re used in increasingly diverse contexts, and as much as quick humor is involved, the same gif can be recontextualized multiple times. One poorly-made animation can take on a multiplicity of meanings. This recent interview on Neiman Journalism Lab with Jessica Bennett covered many of the more serious use of GIFs — and the piece is a great read.

(6) The use of GIFs exploded in new areas in 2012, particularly animated GIFs, hence the importance of the verbal form. Check out a Google Trend search of “gif”. However, the file format’s overall share in web images is declining. Whether it’s a passing trend to vanish in 2013 remains to be seen. (*updated: 15 Nov, see below)

(7) We appreciate all the GIF puns. Keep them coming.

Do you have any questions about GIF? About the Oxford Dictionaries USA Word of the Year? Leave them in the comments below.

Alice Northover joined Oxford University Press as Social Media Manager in January 2012. She is editor of the OUPblog, constant tweeter @OUPAcademic, daily Facebooker at Oxford Academic, and Google Plus updater of Oxford Academic, amongst other things. You can learn more about her bizarre habits on the blog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only lexicography and language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about the New Oxford American Dictionary on the  or visit oxforddictionaries.com.

or visit oxforddictionaries.com.

Image credit: All images are hyperlinked to their sources. NatGeo for the sky, NYPL the ruins, WSWCM for Britney.

*Updated 15 November 2012 to include information from Zachary M. Seward’s article from The Atlantic.

A lovable bully

Bullying is a hot topic. Strict laws have been passed with the view of intimidating the intimidators or at least keeping them at bay. Regardless of the consequences such measures may have, linguists cannot ignore the problem and keep out of the public eye. So to arms, comrades!

That a word like bully should vex etymologists needn’t surprise anybody. As I have said many times, nasty words tend to have irritatingly obscure histories; apparently, they have a good deal to hide. In English texts, bully surfaced around the middle of the sixteenth century and meant “sweetheart, darling,” originally applied to either sex but later only to men (the sense was “good friend; fine fellow”). Shakespeare treasured this word and used it regularly beginning with 1600. One can even suspect that at that time it was jocular street slang. Judging by phrases like lovely bully and “What saiest thou, bully, Bottom,” it occupied a place comparable to that of today’s ubiquitous dude.

Since the word is so late, its supposed derivation from Dutch (such is the verdict of the best authorities) should not encounter any objections. Bully might well be an adaptation of Middle Dutch boele “lover.” Its Modern Dutch continuation is boel “mistress, concubine”; compare German Buhle “lover” and Nebenbuhler “rival.” Boele, it seems, crossed the channel with hundreds of other Dutch words, now perfectly domesticated in English. Most people have heard about the Viking raids, the Norman Conquest, and the influence of both events on the vocabulary of English, but few are aware of the “Dutch conquest,” indeed not a military but a linguistic one. Technical terms, nautical vocabulary, slang, and numerous everyday words reached England in the early modern periods from the Low Countries, though it is often hard to tell whether they came from Northern German or Dutch.

It has been known for a long time that, alongside bully, Scots and northern English dialectal billy “friend, companion” exists. Its origin is also obscure (from the proper name?), so that it provides no clue to the history of bully; perhaps a coincidence. Although the etymology of the Dutch word need not delay us here, especially because opinions on this subject are divided, we will have to return to it closer to the end of our story. The puzzling thing is that bully “lover; friend; fine fellow” disappeared about two hundred years after it had its heyday in English. Only bully as part of historical “titles,” as in bully captain and bully doctor, is a distant echo of that sense. Other than that, we know bully “swashbuckler; blustering browbeater.” I doubt that bully “excellent” is another relic of bully “lover”; more likely, it is an analog of damned good and awfully funny, in which words suggesting horror and perdition are emphatic variants of extremely. The modern senses of bully were preceded by “hired ruffian” and “protector of prostitutes,” that is, “pimp.”

From a lover to a bully. Florida Grand Opera production of Carmen.

Are bully “sweetheart” and bully “ruffian,” from a historical point of view, the same word? OED thought so (I say thought, rather than thinks, because Oxford’s etymological team has not yet revised the first letters of the dictionary.) According to James A.H. Murray, “[t]here does not appear to be sufficient reason for supposing that the senses under branch II. [that is, bully “ruffian”] are of distinct etymology: the sense of ‘hired ruffian’ may be a development of ‘fine fellow, gallant’ (compare bravo); or the notion of ‘lover’ may have given rise to that of ‘protector of a prostitute’, and this to the more general sense. In the popular etymological consciousness the word is perhaps now associated with bull [animal name]; compare bullock.” (The reference is to the dialectal verb bullock “bully.”)

Meaning can deteriorate or be ameliorated. German Recke “knight errant; hero” is a cognate of Engl. wretch; Engl. mad (an example cited in a recent blog) is a cognate of a Gothic adjective meaning “crippled” and of a Middle High German adjective meaning “beautiful.” At one time, Engl. fond meant “stupid.” Linguistic textbooks are full of such examples. Therefore, theoretically speaking, “sweetheart” might become “pimp” and still later “someone who tyrannizes the weak”; the distance between love and hatred is short. The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology does not disagree with the OED. It only mentions the fact that Middle Dutch boele could be used as a term of endearment or reproach. However, early Modern Engl. bully burdened with mild negative connotations didn’t turn up; it referred to either lovers or scoundrels. Perhaps “pimp” is an ironic extension of “sweetheart,” but “ruffian” and “browbeater” don’t fit in with the word’s earliest attested sense. Later dictionaries, to the extent that they say anything beyond “of obscure origin,” followed the OED. Only Henry Cecil Wyld called the suggested connection between bully “sweetheart” and bully “ruffian” unconvincing.

Stephen Skinner, whose posthumous etymological dictionary came out in 1671, must have known both senses of bully (the OED’s earliest citation for “ruffian” goes back to 1688), for, otherwise, he would not have vacillated among three etymons: burly, bulky, and bulla (the latter because in their bullas Popes threaten and bluster). None of the three words alludes to love or even friendliness, though Middle Engl. burly often meant “noble.” For a long time it was believed that bully was akin to Dutch bulderen “boom, roar,” German Poltergeist “a noisy spirit,” and other words designating noise and disturbance (so, for example, Wedgwood and Skeat in the first edition of his dictionary). This derivation points to a common flaw of many old and, deplorably, new conjectures; the researcher would discover a synonym with a root that matches the item under discussion and not bother about the type of word formation. Assuming that bully is related to bulderen, how was it coined? Did speakers isolate the root bul- and add a suffix to it? By comparison, Murray’s etymology has every advantage, and it is no wonder that both Wedgwood and Skeat gave up their ideas and followed the OED.

We can now return to the Middle Dutch form boele. As noted, its origin is disputable. Most scholars believe that it is a pet name for brother (Dutch broer). Yet I suspect that those who separate broer from boele have a point, mainly because I have seen convincing evidence for separating Engl. brother from buddy and learned to treat such etymologies with suspicion. Anyway, a case has been made that the Old English personal names Bola ~ Bolla and Bula ~ Bulla also originally meant “dear brother; lover.” Even if this were right, we would come closer to solving the etymology of bully “sweetheart” and of its Dutch counterpart but would still be unable to cross the bridge from “sweetheart” to “ruffian.” The usually helpful Century Dictionary ignored the etymology in the OED, made no changes between the first and the second edition (despite one reviewer’s criticism), and took the unity of bully1 and bully2 for granted; it did not explain how the second sense arose. Wedgwood, partly like Murray, wondered whether the bad sense of bully had come “from the conduct of a boon companion or from the special application to the bully of a courtesan, the mate or lover with whom she lives, and calls in to intimidate her customers.” Ernest Weekley attempted to connect various hypotheses and wrote that the initial sense “brother” had been affected by the animal name bull and Dutch bulderen.

With due respect to Murray’s idea, the speedy development from “sweetheart” to “ruffian” seems improbable, and references to bravos, gallants, and aggressive pimps do not go a long way. (I emphasize speedy, because no evidence supports Weekley’s suggestions that bully “lover” may have existed in Middle English; Shakespeare’s joy in using the word seems to prove the opposite.) Such semantic revolutions are easier to understand against the background of societal changes. For example, in Old Norse, during the epoch of military campaigns, víkingr was the name of an honored occupation. When the raids came to an end, former vikings became a pest, and the word’s connotations changed: heroic posturing became a farce. In similar circumstances, the word berserkr, also in the north, altered its meaning from “member of an elite royal guard” to “marauder.” The etymon of German Recke and Engl. wretch denotes “exile.” In one country, a man divorced from home turned into an honored solitary adventurer; in the other, his miserable status came to the foreground. An inner development from “lover; gallant” to “blustering tyrant” is possible, but the alleged unprovoked change occurred too quickly to look credible. A bully good man suddenly became a bully.

I suggest that we are dealing with two different words. A dim light comes from Engl. bulkin, now obsolete, except in Jamaica. It goes back to a Dutch word for a bull calf (a noun with a diminutive suffix) and is used as a term of endearment and as an expression of contempt. Perhaps bully, understood as a cognate of bull, merged with bully “lover.” A timid suggestion along these lines, traceable to Murray’s initial etymology, can be found in several modern dictionaries indebted to the OED. Bully “lover” was probably not “affected” by bull but fell prey to the accidental similarity between them. Bully is bull-y, just as doggie as dog(g)-ie. If so, noisy boon companions and chivalrous pimps, along with their frightened “courtesans,” need not bother us any longer.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credit: Julia Ebner, Adam Diegel & Kendall Gladen in 2009 – 2010 production of Carmen by Georges Bizet (Photo: Gaston De Cardenas), part of FGO’s Opera Free for All project. 20 April 2010. Florida Grand Opera. Photo by Knight Foundation. Creative Commons License. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Should fishing communities play a greater role in managing fisheries?

Marine fisheries around the world are in a state of decline. Each decade the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization reports that a larger fraction of the world’s fisheries are overexploited or depleted. Historical trends in individual fisheries have led some scientists to predict all major fisheries will be collapsed by mid-century. The economic status of these resources is even more dismal. A recent World Bank study concluded that the world’s marine fisheries are capable of generating $80 billion per year in net economic benefits, but if fact generate losses on the order or $30 billion annually due to a combination of government subsidies and failed resource management.

Against this backdrop of doom and gloom, there is growing recognition that fishing communities and private fishermen’s organizations often can play an important role in management and conservation, giving reason for guarded optimism. Such groups have operated for decades, even centuries in some places, but their positive role as fishery managers is only recently being appreciated. Traditionally, scientists and policy specialists have considered fishery management to be the sole province of government regulators.

Fishing communities and organizations often play different roles in developed and developing countries. Governments in developing countries often fail to accomplish basic resource management functions due to corruption, lack of resources and poor organization. These failures can perpetuate open access and thwart even basic conservation norms, such as prohibitions on fishing with dynamite or cyanide. Organized groups of fishermen often can fill the resulting management gaps, by limiting access to the resource, monitoring and enforcing controls on fishing effort and acting collectively to conserve the resource.

Fishing communities and organizations often play different roles in developed and developing countries. Governments in developing countries often fail to accomplish basic resource management functions due to corruption, lack of resources and poor organization. These failures can perpetuate open access and thwart even basic conservation norms, such as prohibitions on fishing with dynamite or cyanide. Organized groups of fishermen often can fill the resulting management gaps, by limiting access to the resource, monitoring and enforcing controls on fishing effort and acting collectively to conserve the resource.

Government can perform an important enabling function by recognizing the private group’s authority to exclude non-members. A group of nine fishing cooperatives in Baja California, Mexico is a well-known success story. These coops were granted exclusive rights to manage lobster and abalone in delimited areas in the 1930s and these rights have persisted to the present. The cooperatives now take responsibility for setting limits on the numbers of active fishermen, boats and traps. They also handle exclusion of non-members, control their own members’ actions and restrict the use of damaging fishing gear. These cooperatives have achieved impressive biological and economic success in managing lobster. In 2004 this fishery became one of the few in the developing world to be certified as sustainable by the Marine Stewardship Council.

Less well-known is the case of community managed fresh water fisheries in Bangladesh. Over 12,000 of these fisheries exist and their potential biological productivity is remarkably high. Until recently management by government had been haphazard, with few limitations on access and little management of any kind. An experimental program in community based management placed roughly 80 of these fisheries under the control of local fishing communities. When compared to fisheries managed under business as usual, the community managed fisheries enjoyed substantially greater fish abundance and catches. Equally impressive were the stewardship actions these communities pursued; often, they established fish sanctuaries to protect breeding stocks, prohibited the use of destructive fishing methods and imposed season closures to limit catches.

Private fishery organizations generally play different roles in developed countries. In some cases they work to enhance stewardship actions that other forms of rights-based management, e.g., individual transferable catch quotas (ITQs), fail to achieve. New Zealand has gone further than other countries in assigning management responsibilities to user groups. The Challenger Scallop Enhancement Company, a cooperative of firms that hold ITQ rights, now takes responsibility for a range of stewardship actions, including spatial management of fishing effort to avoid local depletions, re-seeding of recently harvested areas to re-establish stocks and tightening size limits to conserve stocks. Challenger is also responsible for virtually all enforcement activities. Collectives of quota holders also manage New Zealand’s paua (abalone) fishery. As with Challenger, these cooperatives undertake spatial management and share information on stock abundance among members. They also take stewardship actions, including adoption of stringent size limits and rules on fishing methods that minimize incidental mortality.

In other cases developed country cooperatives can overcome political obstacles that government regulators find insurmountable. One such case occurred in the U.S. pollock fishery, where political difficulties made it impossible to manage with individual catch quotas. The solution was to assign management responsibility to groups of fishing firms organized as cooperatives. These cooperatives set up internal catch quotas for individual members to manage effort efficiently. They also slowed the rate of fishing, which improved the quality of the catch, improved product recovery and saved on processing capacity. These coops also fine-tuned the fishing practices to target the most valuable portions of the stock and to catch them at advantageous times.

There is now substantial evidence that privately organized fishing communities and groups of fishing firms can enhance fishery management, particularly in developing countries where government institutions are weak. Such groups can take collective actions to steward the resource, enforce restrictions on its use and coordinate the efforts of individual members. More generally, collective action in fishery management deserves more attention than it has received from researchers and policy makers. A fish population is a resource is shared by all users, and gains can be achieved by coordinating individual efforts in exploiting it. Even in well-designed individual rights systems such as ITQs, gains often can be achieved by allowing (even encouraging) rights holders to organize themselves to take collective action.

Robert Deacon is Professor of Economics at the University of California, Santa Barbara and an affiliated faculty member in UCSB’s Bren School of Environmental Science and Management. His research focuses on natural resource management and the interface between political systems, resource conservation and policy design. His recent paper, Fishery Management by Harvester Cooperatives, has been made freely available for a limited time by the Review of Environmental Economics and Policy journal.

Review of Environmental Economics and Policy aims to fill the gap between traditional academic journals and the general interest press by providing a widely accessible yet scholarly source for the latest thinking on environmental economics and related policy. The Review publishes a range of material including symposia, articles, and regular features.

Image credit: Photograph of fishermen at work by piola666 via iStockphoto.

November 13, 2012

To gif or not to gif

A further celebration of Oxford Dictionaries USA Word of the Year ‘gif’ with a variation of Hamlet‘s famous monologue. I’ve bolded the new words to make it easier to scan for the changes.

To gif, or not to gif–that is the question:

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of crude animation

Or to take arms against a sea of static

And by opposing end them. To stop, to skip–

No more–and by a frame to say we end

The heartache, and the thousand natural shocks

That image is heir to. ‘Tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wished. To stop, to skip–

To skip–perchance to blog: ay, there’s the rub,

For in that sleep of stopping what blogs may come

When we have shuffled off this mortal file,

Must give us pause. There’s the respect

That makes calamity of extension.

For who would bear the whips and jumps of time,

Th’ oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely

The pangs of despised love, broadband’s delay,

The insolence of office, and the spurns

That patient merit of th’ unworthy takes,

When he himself might his tumblr make

With a bare bodkin? Who would jpegs bear,

To grunt and sweat under a weary life,

But that the dread of connection dropped,

The undiscovered country, from whose bourn

No traveller returns, puzzles the will,

And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than follow others that we know not of?

Thus file type does make cowards of us all,

And thus the native hue of resolution

Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought,

And enterprise of great pitch and moment

With this regard their currents turn awry

And lose the name of action. — Soft you now,

Les Horribles Cernettes! — Nymphs, in thy upload

Be all my sins remembered

Do you have any poetry to celebrate the gif? Or are you still stumped?

Alice Northover joined Oxford University Press as Social Media Manager in January 2012. She is editor of the OUPblog, constant tweeter @OUPAcademic, daily Facebooker at Oxford Academic, and Google Plus updater of Oxford Academic, amongst other things. You can learn more about her bizarre habits on the blog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only lexicography and language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about The Oxford Shakespeare: Hamlet on the

View more about the New Oxford American Dictionary on the  or visit oxforddictionaries.com.

or visit oxforddictionaries.com.

Image credit: David Tennant as Hamlet.

The era of partisan polling

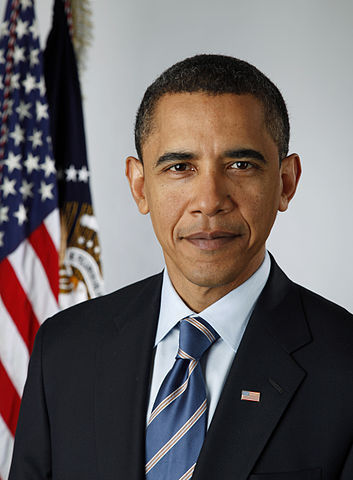

It is tempting now that the election returns are in for us to want to plow forward and forget the spectacular silliness we just traversed. But before we move on, it is critical that we call out those who had predicted a huge Romney victory, among them Dick Morris, Michael Barone, and Karl Rove. Ours is the era of partisan polling, and it is intellectually dishonest and bad for democracy. When Karl Rove held out in disbelief that his predictions were entirely off on Fox News, and Megyn Kelley had to make the awkward walk backstage to the Decision Desk to “verify” their decision, it became abundantly clear that wishful thinking cannot be a substitute for objective reasoning.

This was madness the electorate should not have had to bear. The election was never as close as many had suggested. Barack Obama was ahead in the electoral college most of the last year, and there was never a moment when he possessed less paths to victory than did Romney. Rove cashed in all his credibility from his previous predictions by cooking up a cockamamie story about how all the polls were wrong because they assume a 2008 turnout rate and demographic. However, one of two candidates remained the same between 2008 and 2012; this basic logic of historical induction was enough to convince most posters that 2008 was a useful baseline to make predictions. And they were right. If anything, pollsters had underestimated the turnout and size of the Latino vote.

Then we had the claims about how Barack Obama was underperforming in early voting returns. Well, he won by 53 percent last time. He had 3 percentage points to play with! Denial is one thing, reporting wishful thinking in the name of fairness and balance is another.

Piercing through this wishful thinking is a necessary epistemological step Republicans must take before they even begin to soul-search and rebuild the party. We all make the assumption, often wrongly, that everyone thinks like us. But to operate in the world we must constantly check this instinct, surveying the alternative data and opinions around us. A personal intuition is not a collective summation. Yet already, some Tea Partiers are doubling down on their insistence that the Republicans should have picked a more orthodox candidate. Fortunately, there are voices of reason amidst them.

Obama has won a second term, with an electoral college victory larger than both of the ones his predecessor earned. Obamacare will not be repealed and it will be implemented, and so “greatness” is now within Obama’s reach. He has shown that he is not shy about taking on big problems. The national debt and immigration reform are two of them. “Tonight, you voted for action, not politics as usual,” Obama said on election night. He will be true to his word, though not everyone will like his actions.

Elvin Lim is Associate Professor of Government at Wesleyan University and author of The Anti-Intellectual Presidency, which draws on interviews with more than 40 presidential speechwriters to investigate this relentless qualitative decline, over the course of 200 years, in our presidents’ ability to communicate with the public. He also blogs at www.elvinlim.com and his column on politics appears on the OUPblog regularly.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics and law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

The two-term era

When Barack Obama won re-election last week, he became the third consecutive president to win a second term. The last time that happened was at the beginning of the 19th century, when Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe benefited from Democratic-Republican dominance at the presidential level. Indeed, by the time Monroe ran for re-election in 1820, the opposition Federalist Party had collapsed. No incumbent enjoys the same advantage in the current political environment; there will always be a well-organized, well-funded partisan foe.

Tracing the current pattern back in time a bit further, Obama is the fourth president in the last five to win re-election. Only George H.W. Bush in 1992 failed in his quest to secure a second term. Two terms has become the new normal for American presidents.

Tracing the current pattern back in time a bit further, Obama is the fourth president in the last five to win re-election. Only George H.W. Bush in 1992 failed in his quest to secure a second term. Two terms has become the new normal for American presidents.

Contrast this pattern with what preceded it: between 1960 and 1980, only Richard Nixon won reelection (and, of course, he did not manage to complete his second term). John F. Kennedy might have won in 1964 had he lived. But Lyndon Johnson decided not to seek a second term, and both Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter were defeated in their bid for re-election.

This striking reversal of fortune for sitting president calls for analysis. Several factors may be at work, but one stands out. Most recent incumbent presidents have enjoyed the advantage of early, unified support from their own party.

Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama faced no challenge when they decided to seek renomination. Certainly they had their critics within their own party, especially the Democratic incumbents. Both Clinton and Obama faced murmurings of liberal discontent. But it did not suffice to propel a challenger to enter the fray.

On the other side, George H.W. Bush encountered sharp conservative opposition from Pat Buchanan. Although Buchanan never represented a serious threat for the nomination, he did pressure Bush 41 from the right. Bush’s situation paralleled that of Johnson, Ford, and Carter, each of whom did battle with a popular rival in his own party (Eugene McCarthy, Ronald Reagan, and Ted Kennedy).

With no competition for the nomination, a sitting president does not have to engage in one of the familiar exercises of American electoral politics in the modern era — repositioning himself between the primary season and the general election campaign. Mitt Romney’s attempt to redefine himself in the final months of the campaign, to shake the “etch-a-sketch” once he sewed up the nomination, is a necessary move given the sharp difference between the primary and general electorates.

Dedicated Republican voters today skew far to the right of the population as a whole. This gives a boost to idiosyncratic ideologues (libertarian Ron Paul) or fire-breathing social conservatives (Rick Santorum), who stand no chance of winning in a general election. The make-up of the Republican primary electorate, weighted heavily toward (or, more accurately, weighed down by) Tea Party activists, also forces more moderate or malleable candidates to market themselves as, in Romney’s words, “severely conservative.”

Much the same situation applies in the Democratic Party, with the activists and party-linked interests tilted well to the left. In 2008, Democratic aspirants for the presidential nomination elbowed each other aside in their eagerness to call for the quickest end to the war in Iraq or the most comprehensive version of universal health insurance. Fortunately for the Democrats, their primary electorate makes its peace more readily with the need to line up behind a relatively moderate candidate who can win a general election. Nevertheless, the leftward tug can leave a Democratic nominee with some baggage entering the general campaign.

To secure a nomination by acclamation, as most recent incumbent presidents have done, confers an extraordinary advantage on a candidate. He has the luxury of positioning himself in the political center from the outset. He does not face accusations that he is feckless and unprincipled. He need not worry that any position he takes will alienate either those in his party who supported him during the primaries or middle-of-the-road voters. In an evenly split polity, where campaigns vie for the finicky affections of the independents between the two camps, the incumbent president begins with an important head start.

If this pattern holds in the future, the stakes rise in the next presidential election. With no incumbent on the ballot, we will not be choosing a president for four years, but very likely for eight.

Andrew Polsky is Professor of Political Science at Hunter College and the CUNY Graduate Center. A former editor of the journal Polity, his most recent book is Elusive Victories: The American Presidency at War. ReadAndrew Polsky’s previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Image credit: Official photographic portrait of US President Barack Obama. US government photo.

How we decide Word of the Year [GIFed]

Many people are curious about the process behind the selection of Oxford Dictionaries USA Word of the Year and I thought it would be appropriate to express this in gif form. Here’s my completely biased perspective as blog editor on my first Word of the Year committee.

You receive an email saying you’re on the Word of the Year committee and you feel so important.

But you have to wait a couple weeks for the actual longlist from which you submit your top five choices and the reasons why.

Serious thought is given on lexical interest, significance to this year, and the impact of the word. (Will usage increase? Does it capture the zeitgeist?)

But you’re ruthless in your selections.

A couple weeks after that we receive the shortlist, which contains words you’re not thrilled about.

Finally, the Word of the Year meeting takes place.

We first tackle a couple recent additions to the list that are significant and interesting, but potentially insensitive. Everyone concurs this isn’t the best choice.

We next tackle some intriguing new political words, but everyone is suffering from election fatigue.

Someone suggests a word that Gawker was making fun of five years ago and you don’t see how it says “2012”.

Someone else suggests a word everyone else hates.

Marketing is really pushing for a word, but editorial doesn’t find it lexically significant. Tension rises.

Then someone starts talking enthusiastically about the Higgs boson, but no one else cares.

The meeting becomes increasingly awkward as no clear frontrunner emerges.

Words continue to be nominated and eliminated, and we are in danger of being there all day.

Finally there’s a secret ballot by which time everyone is approaching one of two emotional states:

And the decision is made although no one seems particularly thrilled about it. You have to look vaguely supportive.

Our editorial team has to run it past their dictionary overlords, who disapprove.

One editor expresses interest in the word GIF.

And you agree perhaps this would make a better candidate for WOTY.

So you ask around for people’s thoughts.

Finally, a pitch for GIF as WOTY is made. You brace for the response.

But people actually like the word.

GIF has saved the day.

We must ensure commitment.

And then we finally have WOTY!

And all you want to do is tell people.

But you can’t share the news of the selection. It’s top secret.

And in all the bottled-up excitement, you realize you have to do this all again next year.

Alice Northover joined Oxford University Press as Social Media Manager in January 2012. She is editor of the OUPblog, constant tweeter @OUPAcademic, daily Facebooker at Oxford Academic, and Google Plus updater of Oxford Academic, amongst other things. You can learn more about her bizarre habits on the blog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only lexicography and language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about the New Oxford American Dictionary on the  or visit oxforddictionaries.com.

or visit oxforddictionaries.com.

Image credit: I have made a good faith attempt to find the originators of these gifs, but I can only in certainty ascertain those which are stamped with the originator (example: NatGeo Gifs). If you’re the creator of one of these gifs, please let me know which and I’d be happy to link back to your site. Also let me know if you’d like your gif removed.

November 12, 2012

Why day care should be subsidized

The Nordic countries and France heavily subsidize pre-school child care. In Sweden, parents pay only about ten percent of the actual costs. As a result, about 75 percent of all Swedish children aged one to five are in formal day care. In Germany, where the availability of subsidized day care spots is strictly limited, that number is less than 60 percent, and those German children that are in day care typically spend only a few hours a day there unlike their Swedish counterparts who usually spend all day in a day care center. The consequences for female labour force participation are not surprising. In Germany, 58 percent of women with children up to the age of six were employed in 2004. The corresponding number for Sweden is 78 percent.

What is the case for subsidizing day care? Generally speaking, a market economy works best when the prices people face correspond to actual costs. If I pay in proportion to what I take out of the economy and I am rewarded in proportion to what I contribute, then I have an incentive to do what is best for the economy as a whole. However, the ideal market economy where all prices equal true (marginal) costs and incomes exactly reflect (marginal) contributions is not attainable in practice. Every society needs to fund some goods and services on a collective basis. To do this, the government has to levy taxes. As a practical matter, taxes are levied on income and consumption. So taxes inevitably distort choices by driving a wedge between the social benefit of working and the private reward from working. That’s a given. The question is not how to remove all distortions but how to minimize their damaging effects.

To see why day care subsidies should be part of a damage-minimization tax policy, consider an economy where people have to pay for day care out of their after-tax income. Suppose the pre-tax wage is €10 per hour and that the cost of day care is €2 per hour and suppose the income tax rate is 50 percent. For simplicity, consider a single parent who needs to buy one hour of child care for every hour that he or she works. The social benefit of working, net of real child care costs, is €8. The net reward, after taxes and day care costs, is €3. Thus the effective wedge is 5/8 or 62.5 percent. What is the effective wedge for people without small children? 50 percent of course. So, in this imaginary economy, the choices of parents with small children are more distorted than the choices of others.

There are strong reasons to think that such inequality of wedges is not a feature of the best possible tax system, the one that distorts as little as possible. To verify that properly, we need a mathematical model. But some well-informed intuition will do nicely for now. Presumably it is at least plausible that jelly beans and candy canes should be taxed at the same rate. Why not? So surely parents with young children should be taxed at the same effective rate as everybody else. In our little example, what would it take for the effective tax rate to be 50 percent for everyone? The answer is: a child care subsidy of 50 percent. Then the net reward for working would be €4 per hour or 50 percent of the benefit to society. This is of course not a coincidence. In general, to equalize wedges between people with and without small children, the thing to do is to subsidize it at the same rate as the marginal tax rate. Equivalently, day care expenses can be made tax deductible. Naturally, tax rates for everyone else will have to rise a bit to finance child care subsidies. But even when we take that into account, an equalization of wedges leads to a more efficient allocation of resources.

In the German context, there is another reason (beyond equalizing explicit tax wedges) to subsidize child care, namely that it encourages people to work who otherwise would have lived on social assistance. For single mothers in Germany, the incentives to work are particularly weak, and day care subsidies would strengthen those incentives. Meanwhile, encouraging people to move from living on social assistance into working for a living is good for the government budget, making child care subsidies cheaper for the public purse. We conclude that the best subsidy rate for Germany would be 50 percent.

Is formal day care good for children? The evidence is not entirely clear-cut, and many studies fail to find either positive or negative effects on outcomes later in life for children who went to day care. But a recent study by Havnes and Mogstad provides some very strong evidence that formal day care has been good for Norwegian children, especially for those from disadvantaged backgrounds. Gathmann and Sass find similar results for Germany. Thus there is no strong counterargument based on child development to the efficiency case for child care subsidies.

David Domeij is associate professor of economics at the Stockholm School of Economics in Stockholm, Sweden. He received his PhD in 1998 from Northwestern University. In his research he has mostly focused on public finance and macroeconomics. Paul Klein is associate professor of economics at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada. He received his PhD in 1997 from Stockholm University. In his research he has mostly focused on public finance and macroeconomics. Their recent paper, “Should Daycare be Subsidized,” has been made freely available for a limited time by the Review of Economic Studies journal.

The Review of Economic Studies is widely recognised as one of the core top-five economics journals. The Review is essential reading for economists and has a reputation for publishing path-breaking papers in theoretical and applied economics.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only sociology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Teacher explaining the world to preschoolers by Dean Mitchell via iStockphoto.

November 11, 2012

Remembrance Sunday

Remembrance Sunday, falling on 11 November in 2012 and traditionally observed on the Sunday closest to this date, marks the anniversary of the cessation of hostilities in the First World War. It serves as a day to reflect upon those who have given their lives for the sake of peace and freedom.

We have selected a number of memorable, meaningful and moving quotes from the Little Oxford Dictionary of Quotations and the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations to commemorate the fallen.

“We make war that we may live in peace.”

Aristotle 384-322 BC Greek philosopher

Wilfred Owen 1893-1918 English poet

“Justice inclines her scales so that wisdom comes at the price of suffering.”

Aeschylus c.525-456 BC Greek tragedian

“If I should die, think only this of me:

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is forever England.”

Rupert Brooke 1887-1915 English poet

Laurence Binyon 1869-1943 English poet

“Old soldiers never die.”

Proverb early 20th century

“At eleven o’clock this morning came to an end the cruellest and most terrible war that has ever scourged mankind. I hope we may say that thus, this fateful morning, came to an end all wars.”

David Lloyd George 1863-1945 British Liberal statesman, Prime Minister 1916-22

“Let war yield to peace, laurels to paeans.”

Cicero (Marcus Tullius Cicero) 106-43 BC Roman statesman, orator, and writer

“And some there be, which have no memorial… and are become as though they had never been born…

But these were merciful men, whose righteousness hath not been forgotten…

Their seed shall remain for ever, and their glory shall not be blotted out.

Their bodies are buried in peace; but their name liveth for evermore.”

The Bible, Apocrypha (authorized version, 1611)

“When you go home, tell them of us and say,

‘For your tomorrow we gave our today.’”

Kohima memorial to the Burma campaign of the Second World War, from a poem by John Maxwell Edmonds

John McCrae 1872–1918 Canadian poet, doctor, soldier

“Mankind must put an end to war or war will put an end to mankind.”

John F. Kennedy 1917–63 US Democratic statesman and thirty-fifth president of the USA (1961–63)

“In war: resolution. In defeat: defiance. In victory: magnanimity. In peace: goodwill.”

Winston Churchill 1874–1965 Prime Minister 1940-45, 1951-55

The Little Oxford Dictionary of Quotations fifth edition was published in October this year and is edited by Susan Ratcliffe. The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations seventh edition was published in 2009 to celebrate its 70th year. The ODQ is edited by Elizabeth Knowles.

The Oxford DNB online has made the lives of Wilfred Owen, Rupert Brooke, and Laurence Binyon free to access for a limited time. The ODNB i s freely available via public libraries across the UK. Libraries offer ‘remote access’ allowing members to log-on to the complete dictionary, for free, from home (or any other computer) twenty-four hours a day. In addition to 58,000 life stories, the ODNB offers a free, twice monthly biography podcast with over 130 life stories now available. You can also sign up for Life of the Day , a topical biography delivered to your inbox, or follow @ODNB on Twitter for people in the news. The ODNB also has a special free access area about the First World War, called Armistice lives.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language, lexicography, word, etymology, and dictionary articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about the Little Oxford Book of Quotations on the

View more about the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations on the

November 10, 2012

10 November 1975: Daniel Patrick Moynihan addresses the UN on Zionism

Before Daniel Patrick Moynihan (1927-2003) was elected as a Democratic Senator from New York in 1976, a seat he held 24 years, he served as the United States Ambassador to the United Nations. While Moynihan was the ambassador, the UN passed Resolution 3379, which declared “Zionism is a form of racism and racial discrimination.” In the new book Moynihan’s Moment: America’s Fight Against Zionism as Racism, historian Gil Troy chronicles Moynihan’s fiery response to that resolution, a speech that was delivered 37 years ago today. Moynihan’s speech was very popular — Ronald Reagan was even a great admirer of it — and Troy shows how Moynihan’s “politics of patriotic indignation” has continued to influence US foreign policy, even to the present day. An excerpt from Moynihan’s Moment and the video clip of the speech is below.

On November 10, 1975, the United Nations General Assembly passed Resolution 3379 with 72 delegates voting “yes,” 35 opposing, 32 abstaining, and 3 absent. In the world parliament’s dry, legalistic language, the resolution singled out one form of nationalism, Jewish nationalism, for unprecedented vilification. “Recalling” UN resolutions in 1963 and 1973 condemning racial discrimination, and “taking note” of recent denunciations of Zionism from the International Women’s Year Conference, the Organization of African Unity meeting, and the Non-Aligned Conference in Peru that summer, the General Assembly concluded that “Zionism is a form of racism and racial discrimination.”

After the resolution passed, America’s ambassador to the United Nations, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, rose to speak. With his graying hair and matching gray suit, a white handkerchief in his breast pocket, from afar the forty-eight-year-old American looked like every other middle-aged Western diplomat.

Up close, the 6-foot 5-inch professor made a different impression. His hair was a little long and untamed, more Harvard Yard than Turtle Bay, the fashionable New York neighborhood where the UN is located. Strands of hair drooped over the right side of his prominent forehead, compelling him to brush back the errant hair periodically. With a no-nonsense scowl reinforced by arched eyebrows on his oblong face, Moynihan undiplomatically denounced the very forum he was addressing.

Click here to view the embedded video.

“The United States rises to declare,” Moynihan began his formal address, swaying gently, both hands clutching the podium, “before the General Assembly of the United Nations, and before the world, that it does not acknowledge” — he paused — “it will not abide by” — he paused again — “it will never acquiesce in this infamous act.” Later on, he proclaimed, “The lie is that Zionism is a form of racism. The overwhelmingly clear truth is that it is not.”

Soviet-engineered, absolutist, and impervious to changing conditions, the Zionism-is-racism charge fused long-standing anti-Semitism with anti-Americanism, making it surprisingly potent in the post-1960s world, despite being a political chimera. In the Iliad, a Chimera is a grotesque animal jumble, “lion-fronted and snake behind, a goat in the middle.” To make Israel as monstrous, Resolution 3379 grafted allegations of racism onto the national conflict between Palestinians and Israel. This ideological hodgepodge racialized the attack on Israel and stigmatized Zionism, for race had been established as the great Western sin and the most potent Third World accusation thanks to Nazism’s defeat, America’s Civil Rights’ successes, the Third World’s anti-colonial rebellions, and the world’s backlash against South African apartheid.

Criminalizing Zionism turned David into Goliath, deeming Israel the Middle East’s perpetual villain with the Palestinians the perennial victims. This great inversion culminated a process that began in 1967 with Israel’s imposing Six-Day War victory, followed by the Arab shift from conventional military tactics to guerilla and ideological warfare, especially after the 1973 Yom Kippur War. Viewing Israel through a race-tinted magnifying lens exaggerated even minor flaws into seemingly major sins.

The vote shocked many, especially in the United States, the country largely responsible for founding the UN and justifiably proud of hosting the UN’s main headquarters in New York. The prospect of this non-Jewish society rising with such unity and fury against anti-Semitism provided a rare sight in Jewish history. Only in America, it seemed, would so many non-Jews take Jew hatred so personally. The reaction to Resolution 3379 further demonstrates American exceptionalism, expressed in this case by the extraordinary welcome Jews, Judaism, and Zionism have enjoyed in the United States, particularly after World War II.

Gil Troy is a leading presidential historian and one of today’s most prominent activists in the fight against the delegitimization of Israel. He is Professor of History at McGill University and a Research Fellow in the Shalom Hartman Institute’s Engaging Israel Program. Professor Troy is the author of ten books, including Moynihan’s Moment: America’s Fight Against Zionism as Racism, The Reagan Revolution: A Very Short Introduction, Leading from the Center, Morning in America, and Why I am a Zionist. Troy’s writings have appeared in The New York Times, The New Republic, and other major media outlets. He writes a weekly column for The Jerusalem Post, and is Editor-at-Large of The Daily Beast’s Open Zion blog. You can follow him on Twitter at @GilTroy and read his previous post on the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers