Matthew Dicks's Blog, page 42

September 30, 2024

Flat tires

I saw this truck on the streets of San Fransisco this weekend.

Sometimes, I see something like this, and I wish I had the time and gumption to ask questions, understand more, and discover the life behind this truck, this business, and this life.

The world is full of unknown wonders that sadly remain unknown.

September 29, 2024

Tragedy behind glass

Tragedy strikes.

In 1994, I ran for President of Manchester Community College’s Student Council.

It wasn’t the best decision of my life.

I was already managing a McDonald’s restaurant full-time and serving as President of the National Honor Society. I worked part-time in the school’s writing center, helping students with their work, and I was studying like hell to achieve academic excellence.

I eventually was named to USA Today’s Academic All-American Team and became a finalist for the Truman Scholarship, all of which led to full scholarship offers from Yale, Wesleyan, and Trinity.

Moving on to a four-year school might have been impossible without those scholarships, and I knew it. I needed to do exceptionally well in every class without exception.

Despite all of this, I ran for President, mainly because my friend Chris was running for Vice President and asked me to join him on the ticket. Since Presidential and Vice Presidential candidates weren’t running together on a single ticket back then, he thought we might have a chance to win if we approached the election strategically.

I agreed. It sounded like a great plan. Despite having no time, I plastered the campus with posters, shook lots of hands, debated my opponents, and delivered stump speeches.

It didn’t work. I lost by 14 votes to a woman named Jane, who failed to show up for the next semester. Thus, Angela—the VP candidate who had beaten Chris—became the new President.

However, the Treasurer-elect also failed to return the following semester, so Angela asked me to fill the role. She also asked Chris to join the Student Council as an Executive Senator.

Not exactly the president and vice president, but it was enough to get us an office on campus, overnight trips to Washington DC and New York City for leadership summits, and most importantly, our own computers on campus.

In 1994, no one owned a laptop, and smartphones did not exist. The internet was barely operational by today’s standards. Work was completed with pen and paper or at home on massive desktop computers, so having a computer and printer on campus at my disposal, in an office of my very own, was a game changer.

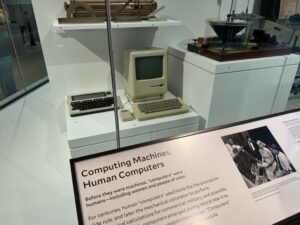

That computer:

An early Apple computer, complete with a floppy drive.

Last weekend, tragedy struck when I saw that computer displayed in the Peabody Museum.

It’s the first time something I once used is now behind glass in a museum.

I’m not happy about this at all.

September 28, 2024

AbeBooks Weird Book Room

The internet is a place of beauty and disaster.

I sometimes wonder if we would be better off without it. As a member of Generation X—the last generation to straddle the analog and digital worlds—I remember the world before the internet well.

I grew up analog. I negotiated on paper maps, made calls on phones affixed to walls, and read physical encyclopedias.

Then, sometime in my twenties, the internet appeared in its nascent form—quirky, clunky, and amusing. It was more of a toy at first, offering silly ideas and ridiculous websites. In many ways, it was more of a toy at first—something new but hardly necessary.

Then, useful tools like email emerged, making our lives easier. Businesses began to stake out digital territory. Card catalogs moved online.

Eventually, the internet became a necessary part of everyone’s life. Then, it moved onto mobile devices, and they, too, became essential to modern life.

It’s a wondrous thing. Much of my work today would be impossible without it.

But it’s also allowed the most monstrous people to find like-minded monsters, affording them a platform to project their hate. It’s turned lies into weapons. It’s degraded truth and created an army of people willing to believe the dumbest things.

I remember those analog days clearly, and they weren’t so bad.

Then I stumble upon this — AbeBooks’ Weird Book Room, “the finest source of everything that’s bizarre, odd, and downright weird in books” — and I’m reminded of the beauty of the internet.

This is an online store for some of the strangest books I’ve ever seen. The titles alone are worth reading, but they are so strange that I might need to purchase them just to see what’s inside.

And if you’re looking for a gift for the person who has everything, might I suggest one of the titles below?

This is a reminder of the internet of yore:

A place where unusual ephemera is gathered to delight and amuse an audience.

We need more of this.

September 27, 2024

Childhood bedrooms

In recent decades, it’s become increasingly common for kids growing up in the United States to have their own room and not share a room with a sibling. This is the result of a couple of trends, including bigger houses and fewer kids per family.

As a result, the average number of bedrooms per child in the U.S. — according to census data — increased from 0.7 to 1.1 from 1960 to 2000.

That said, there isn’t much evidence that either setup—independent rooms or bunking with a sibling—has any particularly positive or negative long-term impacts.

But what I’m wondering is this:

What’s up with the 1.1 bedrooms per child?

Why does the average American child have more than one bedroom?

Are these just guest bedrooms being counted as children’s bedrooms?

I hope so.

What kind of parent gives their child two bedrooms in their home?

For much of my childhood, my siblings and I shared two bedrooms. Two boys—later three when my mother remarried and we added a stepbrother—shared one room. My sister, and later a stepsister, shared another.

But when I turned 14, I moved into an unheated room in the basement — a paneled box in the middle of a cold, often wet concrete space. It was dark, chilly, dank, and my own.

My mother repeatedly denied me permission to move into the basement, citing the temperature and general awfulness of the room, so I waited for a weekend when they were away and moved downstairs anyway.

Once you’ve established a beachhead, you’re hard to dislodge.

It took my parents two days to even realize I was now living in the basement, and when they did, they decided not to protest.

Eventually, this basement bedroom became especially helpful when things went south with my stepfather, and I began entering and exiting the home via the hatchway—the bulkhead in my childhood parlance — and avoiding the upstairs altogether.

Yes, I had to pile blankets atop me to stay warm in the winter, and the furnace and water heater made quite the racket at night, but the apace was my own, and I suspect my brothers were happy to be rid of me.

So yes, I was one of those kids who had his own room—at least for a few years—but it was hardly palatial.

It probably prepared me well for the cruddy little apartments and homelessness that was to come before I managed to get myself on solid footing.

Had I occupied 1.1 bedrooms during my childhood, the shift to my considerably reduced accommodations would’ve been quite a shock to the system.

September 26, 2024

Thinking beyond the recipe

When I met my wife, I could cook a few things. Chief among them was Kraft Macaroni and Cheese with hotdogs, which my wife found delicious.

Having been raised on more healthy fare, this processed monstrosity was a welcomed change from whole grains and terrible vegetables.

I could also grill a burger and make most breakfast foods, but that was the extent of my cooking skills.

Then the pandemic hit, and to avoid the grocery store as much as possible, we ordered meal kits from Hello Fresh, complete with easy-to-follow recipe guides. By the end of the year, I could cook dozens, if not hundreds, of new dishes.

I also learned valuable skills like mincing, dicing, grating, testing, searing, and broiling.

Give me a recipe, and I could do it all.

But I was lost when I didn’t have a Hello Fresh meal kit. With a refrigerator full of food, I didn’t know what to make. So one day, I asked my wife how to throw things together like she did to produce something delicious. She opened the refrigerator and pantry and taught me how to think beyond the recipe card.

It took some time, but today, I can look at our ingredients in stock and almost always prepare something yummy. I’m not nearly the cook that Elysha is, but I can hold my own and feed my family with relative ease.

Sometimes, you need an expert to show you the way.

This is why I’ve decided to launch Storytworthy’s first Mastermind. As we prepare to launch the new, expanded, and much-improved version of my Storyworthy for Business course, I began thinking:

This course is outstanding for people willing to learn independently — watch videos, experiment, practice, and improve at their own pace.

But what about those who want or need an expert—someone who does the job well and knows how to teach exceedingly well—to guide them along the way?

What about those storytellers and would-be storytellers who need a Troy?

That is why I am launching the first semester of the Storyworthy Mastermind — an opportunity for a dozen people to spend six months learning to tell stories alongside someone who does it well and knows how to teach it well — me.

By joining my Storyworthy Mastermind, you will receive more than 20 hours of group and individual instruction, weekly video and email updates and lessons, an invitation to a community of like-minded people to help you along the way, my brand-new Storyworthy for Business course (which will serve as our curriculum), and a one-year membership into Storyworthy’s VIP program, giving you access to every course I have and will produce.

If you’re looking for a more guided approach to learning to tell stories — complete with individualized instruction and constant feedback — this Mastermind may be for you.

Registration opens soon.

Click here to join the waiting list, be one of the first to learn about the Mastermind in detail, and have the opportunity to join.

Teachers on a time clock

It’s come to my attention that one proposal in our current teacher contract negotiations requires teachers to arrive at school 30 minutes before the school day and remain at school an hour after the school day has ended.

Happily, I don’t know where this idea originated, so I am attacking its stupidity and cruelty rather than the specific person responsible for it.

The person responsible for this idea may feel attacked if they ever read this, but I can’t help that. If you have a stupid idea, that is your fault.

First, and perhaps most important:

Most teachers arrive 30 minutes before the school day begins and remain at school an hour after the final bell rings.

For transparency, I arrive at school about an hour before the school day begins but only remain in the building for 15-30 minutes after the final bell has rung. But I have been teaching for 26 years — the last 16 at the same grade level — so things have become easier over time. When I first started teaching, I would arrive at school at 5:00 AM — alongside my principal at the time — and leave around 5:00 PM.

But I was inexperienced and dumb back then. I needed every minute I could get.

But I’m also married to a teacher who arrives an hour before the school day begins and usually remains at work more than an hour after the day has ended. She also frequently works on weekends to prepare for the coming week, goes to school on Sundays to ensure her lessons are ready, and routinely spends unpaid summer vacation days in her classroom, preparing for the coming year.

And herein lies the stupidity of this proposal:

It ignores the endless number of hours that teachers already spend working outside the school day.

They correct papers after dinner, plan lessons after their own children have gone to bed, go to school on the weekends to prepare materials, search online for new ideas into the wee hours of the night, and work in the summer on their classrooms and plans. They call parents and respond to emails in the evening, on the weekends, and everything in between.

These are the last people who should be nicked and dimed regarding their time.

All they do is give their time.

I don’t know a single teacher who doesn’t work outside the school day.

I don’t know a single teacher who doesn’t surrender summer days to prepare their classrooms since school districts never allow adequate time to complete this task.

The average teacher spends enormous amounts of time outside of the school day already.

Administrators know this. If they don’t, they need to open their office doors and take a look around.

These are people who also routinely spend their own money on their students and classrooms. These professionals often turn to online resources like Teachers Pay Teachers for quality curriculum and practice problems when the curriculum provided by the school district fails them. They purchase pencils and notebooks for students, posters and fabric to make their classroom more bright and inviting, and even furniture and storage units when needed. I know teachers who spend their Saturday mornings scouring garage sales for books to add to their classroom libraries because almost every classroom library that has ever existed has been paid for by teachers or acquired via donations.

If anything, administrators and school boards should be ashamed of themselves for failing to adequately support teachers. Every dollar a teacher spends on their students and classrooms — and nearly every teacher I know (including the teacher I live with) does this — should serve as a source of embarrassment to school districts and a clarion call that basic needs are not being met.

These are people who routinely prioritize their students over themselves and their own children, sending dollars back into the school instead of pouring them into retirement accounts, vacation spending, and college funds for their children.

They do all this, and then some fool says that these angels of humanity must stick around after school for an hour every day.

Lawyers, doctors, accountants, branding specialists, FBI agents, salespeople, CEOs, web designers, rabbis, marketers, politicians, and nonprofit leaders—all people I work with regularly—are not required to spend their own money on the needs of their customers or clients.

They do not spend their own money on their workspaces.

Teachers do this every day.

None of these professionals punch a virtual time clock or are required to remain inside a building when their work can be completed whenever and wherever they want.

I know this because I work with these people every day.

If teachers began adhering to their actual contract — only working at the designated time for the required number of hours — and ceasing to spend their own money on their classrooms, the punch to the gut to the school system would be astounding.

Students would feel it immediately. Parents, too.

If the work that teachers do outside their contracted hours evaporated overnight, children would suffer mightily. Education would degrade rapidly. Test scores would fall precipitously.

But this would never happen, and administrators and politicians know this. Teachers care too much about their students to allow it to happen. It’s this level of concern, commitment, and authentic, genuine love teachers feel for their students that allows terrible people to routinely take advantage of educators, knowing that whatever demands are placed upon them will likely be accepted because children’s futures are at stake.

I know a teacher who was crying in school this week—not because she was upset about a work issue — but because her back hurt so much that she was brought to tears.

Why was she at school?

She loves her students.

I returned from hernia surgery two weeks early and spent those two weeks in pain, mostly rolling around in a swivel chair while I taught. I’ve returned to school early from pneumonia twice despite my doctor’s protestations to stay home and rest.

Why? I love my kids.

I know a teacher who has put off surgery to alleviate great pain and deal with a serious health issue for months to avoid being absent from their students, even when they had more than enough sick days to accommodate the absences.

I know teachers suffering from COVID who continued to teach remotely during the pandemic despite high fevers and other serious symptoms.

Why? They were worried about their students, trapped at home, missing a lesson or a wellness check.

Most teachers have dozens—if not hundreds—of contractually allotted sick days banked that they will never use and never be paid for. Similarly, most never use their contractually allotted personal days.

I currently have 204 sick days in the bank. I’ve used about a dozen of the 54 personal days allotted to me over my career.

Why?

When I’m not feeling well or am injured, I try like hell to go to school.

I try to schedule doctors and dentist appointments after work or in the summer.

Most, if not all, teachers do the same.

If every teacher in my school district began taking every contractually allotted, legally allowed sick and personal day every year, the district would collapse.

Teacher shortages would be overwhelming.

Students would suffer.

There are likely tens of thousands of unused sick days in my school district — unused because teachers love their kids and want to be in school.

But now, someone thinks it’s a good idea to nickel and dime teachers on work hours when we exceed our contractually required work hours every damn week?

Are they blind?

We live in a world where inflation has exceeded 14% over the past three years, and the average American’s average wage growth has matched or exceeded that number.

The average American wage has increased by 13.5% over the past three years.

Yet school districts routinely offer annual salary increases of 1 or 2%.

The United Autoworkers Union—which works in an industry the government recently bailed out—won a 23% pay increase in 2023.

They do important work — building cars and trucks.

But teachers do pretty important work, too. They educate children, teach future UAW members, and prepare UAW leaders to negotiate for better pay.

Nevertheless, teachers are asked to accept minuscule pay increases, which means that, relative to inflation, they have taken at least a 12% pay cut every year for the past four years.

In the shadow of this absolute economic reality, the asinine stupidity of trying to extend a teacher’s required school day while failing to compensate them enough to simply match inflation is shortsighted, cruel, and stupid.

The proposal will likely never pass. Teachers would never agree to such nonsense. But the damage has already been done. The message is clear:

You may already be working outside of your contracted work hours—before school, after school, and in the summer—but we don’t care. We want to lock you down and dictate where and when you work at all times.

You may be piling up sick and personal days because it’s more important for you to be with your students, but we don’t care. We want you correcting those papers and preparing those lessons at your desk, damn it.

You may be doing all this while your salary increases lag behind the national average by at least ten percent and during highly inflationary times, but we also don’t care. We want to put you on a time clock.

We want to treat you like students — dictating where and when you’ll complete your work.

In short, we don’t see you as professionals.

That is the dumbest part of the proposal. It reminds teachers they are undervalued and underappreciated and not seen as professionals. It tells teachers that all the sacrifices they make for students and their schools—both with their time and wallets—are irrelevant in the eyes of administrators.

It’s a proposal that damages morale. It makes teachers question their choice of career, and it makes future teachers hesitant about entering the profession.

It’s shortsighted, stupid, and lacks any semblance of decency.

I can’t begin to imagine what the person proposing this was thinking.

My hope: They weren’t thinking.

My worry: They were thinking clearly, and this proposal reflects their perceptions of the educators.

Either way, the damage has been done.

September 25, 2024

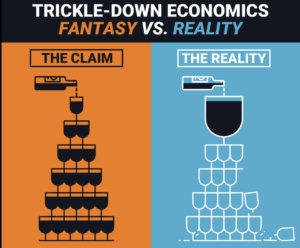

Trickle down economics was a joke gone very wrong

Trickle-down economics was first embraced by Ronald Reagan in 1980. It refers to economic policies that disproportionately favor the upper tier of the economic spectrum, comprised of wealthy individuals and large corporations. The policies are based on the idea that spending by this group will “trickle down” to those less fortunate in the form of stronger economic growth.

While some politicians still espouse this theory, it has been an abject failure. Economic inequality has surged since 1980. Wealthy households have seen historic rises in their income, while middle-class families have been left behind.

The evidence could not be clearer, yet the belief persists today, primarily as a rationale for politicians to reduce the levels of taxation on wealthy people, even if it continues to exacerbate economic inequality and strain the social fabric of our country.

Here’s the crazy part:

Satirist and humorist Will Rogers invented the term “trickle-down” economics as a joke, stating clearly that this type of economy would make the rich richer and the poor poorer.

In a 1932 column criticizing Herbert Hoover’s policies and approach to The Great Depression, Rogers wrote:

“This election was lost four and six years ago, not this year. They [Republicans] didn’t start thinking of the old common fellow till just as they started out on the election tour. The money was all appropriated for the top in the hopes that it would trickle down to the needy. Mr. Hoover was an engineer. He knew that water trickles down. Put it uphill and let it go and it will reach the driest little spot. But he didn’t know that money trickled up. Give it to the people at the bottom and the people at the top will have it before night, anyhow. But it will at least have passed through the poor fellow’s hands. They saved the big banks, but the little ones went up the flue.”

A satirist wrote a joke about an ineffective, stupid policy, and 48 years later, a Presidential hopeful latched into the name, despite its origin, and made it the cornerstone of his election campaign and Presidency.

The result?

Exactly what Will Rogers predicted.

The little ones went up the flue.

September 24, 2024

No more guitar solos

The last rock song to reach #1 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart was Nickelback’s “How You Remind Me.”

It was released in August 2001 and peaked at #1 on December 21, 2001.

Since then, there hasn’t been a rock song to reach #1.

Coldplay’s “Viva La Vida” reached #1 in 2008 but isn’t classified as a rock song and doesn’t sound like one.

The fact that Nickleback was the last rock band to reach #1 is a real punch in the face for rock fans. No shade on Nickleback, but the last standard bearer of rock music—at least to date—is often criticized for being objectively boring and lacking genuine substance. It’s panned for reflecting elements of more successful bands while being overly commercial and inauthentic.

A million Nickleback jokes have been told, and a million more will likely be told, yet the band is the last to reach the top of the charts with a rock song.

Bah.

This isn’t to say that rock music is dead. Many rock bands are performing today, and many are hitting the charts, but none are even close to reaching #1.

It makes no sense to me.

While I love many kinds of music and like many of the songs hitting #1 today, I adore the beauty, simplicity, and clarity of a guitar, a bass, a drum, and a lead singer.

The less production that goes into a song, the better.

Apparently, not everyone agrees with me anymore.

September 23, 2024

Steve saw me.

Over the past 26 years as a teacher, I have received an untold number of hours of professional development.

A glacier of training.

An ice age of strategies, readings, worksheets, activities, and skills.

I’m sure that along the way, this professional development has impacted my pedagogy and practice, but it was rarely transformational.

I never left a professional development session thinking, “I am going to be a better teacher tomorrow because of the time I spent today.”

Except once.

A few years ago, a colleague and fellow teacher named Steve spent a full school day watching me teach.

That day was more transformational to my teaching than all the other professional development I have received combined.

Hundreds—maybe thousands—of hours of professional development did not add up to one day of assistance from Steve.

Why?

Steve was an excellent teacher who spent his days with students. He was doing the job, and he understood its challenges better than any administrator ever could.

And on that day, he observed me closely. Took notes. Analyzed my decision making. Dissected my practice.

He applied his expert lens to my practice and came away with valuable insights into my practice.

At the end of the day, Steve spent 20 minutes reviewing his assessment of my work. He told me things that I did well and suggested areas for improvement.

Both of these things things transformed me as a teacher forever.

Among the things Steve told me:

I give more positive feedback than any teacher he had ever seen, which I did not know. While I was already doing this well, the awareness that Steve provided allowed me to become more consistent, more targeted, and more strategic with my positive feedback.

Steve took something I already did well and elevated it to new heights.

Steve also noticed how my instruction tends to lean toward auditory learners.

I wasn’t surprised since I am also an auditory learner.

I remember almost everything I hear but almost nothing I see.

This is what made me the state’s collegiate debate champion two years in a row.

As a result, I was unconsciously favoring the type of learning that served me best. I wasn’t failing my less auditory students, but I wasn’t scaffolding their instruction to the degree they could learn best.

Steve offered me simple strategies that would allow visual learners, students who need more time to process before sharing, and students for whom English is not their first language to be better prepared for classroom discussions, partner sharing, and the like.

I still use these strategies today—I use them every day. Thanks to Steve’s observation, I’ve also researched additional strategies, and I am absolutely a better teacher today as a result.

A hell of a better teacher.

Those are just two of a dozen or more things Steve offered me that transformed my teaching for the better. Pile up 26 years of professional development, and none of it comes close to what Steve offered me that single day.

Sometimes, you need someone by your side—an expert—to observe you, guide you, and make you better.

This is why I’ve decided to launch Storytworthy’s first Mastermind. As we prepare to launch the new, expanded, and much-improved version of my Storyworthy for Business course, I began thinking:

This course is outstanding for people willing to learn independently — watch videos, experiment, practice, and improve at their own pace.

But what about those who want or need an expert—someone who does the job well and knows how to teach exceedingly well—to guide them along the way?

What about those storytellers and would-be storytellers who need a Steve?

That is why I am launching the first semester of the Storyworthy Mastermind — an opportunity for a dozen people to spend six months learning to tell stories alongside someone who does it well and knows how to teach it well — me.

By joining my Storyworthy Mastermind, you will receive more than 20 hours of group and individual instruction, weekly video and email updates and lessons, an invitation to a community of like-minded people to help you along the way, my brand-new Storyworthy for Business course (which will serve as our curriculum), and a one-year membership into Storyworthy’s VIP program, giving you access to every course I have and will produce.

If you’re looking for a more guided approach to learning to tell stories — complete with individualized instruction and constant feedback — this Mastermind may be for you.

Registration opens soon.

Click here to join the waiting list, be one of the first to learn about the Mastermind in detail, and have the opportunity to join.

No inner monologue?

A new study shows that not everyone has an “inner voice” in their heads. The extent and intensity of that voice vary considerably from person to person, impacting how people think.

They found considerable differences, for example, in performance on given tasks, indicating that those with strong inner monologues are better at retaining and manipulating information with accuracy and rapidity.

My question:

Who doesn’t have an inner monologue?

I’m talking to myself constantly. I’m often talking to myself while I’m talking.

Years ago, I told a storytelling student—a doctor in the emergency department at Yale New Haven Hospital—that while I am telling a story, performing standup, or delivering a speech, I’m often talking to myself at the same time—monitoring audience reaction, adjusting content and delivery on the fly, and noting other things in the room.

She didn’t believe me. “You can’t be talking to yourself while talking to an audience.”

I assured her I was telling the truth and explained that as you grow more proficient at public speaking, you will require less bandwidth to do the job. At some point, you have enough bandwidth to both speak to audiences and yourself simultaneously.

When I perform “Matt and Jeni Are Unprepared” — a storytelling improv show with my friend, Jeni Bonaldo—I constantly speak to myself because I am telling a brand new story in front of an audience without any preparation whatsoever.

The same is true when I perform standup. While I may have a plan when I take the stage, new ideas almost immediately materialize, and I need to decide which ideas make the cut and which should be avoided. That decision-making process happens while simultaneously trying like hell to be funny.

And I’m not a unicorn. I know other public speakers who report the same thing. While I suspect that many people who speak to audiences stick to the script and don’t possess this version of an inner monologue, those of us who spend enormous amounts of time onstage and speak for an hour or more probably do.

But my friend still didn’t believe me.

Two years later, she called me. “I can’t believe it,” she said. “I was just delivering a talk to my department, and I realized that while I was speaking, I was talking to myself. I even reordered a part of my talk midstream and debated with myself if it made sense.”

I then spoke four of my favorite words:

“I told you so.”

After two years of public speaking, she had reduced the bandwidth required to speak—including the nervousness that she felt while speaking—thus affording herself enough to engage in an inner monologue.

Yet, according to this recent research, some people have little or no inner monologue at all.

It’s hard to believe that, for some people, it’s just a vacuous, silent space between their ears.

No interior monologue.

No constant questioning.

No endless plotting.

But perhaps silence might also be a welcomed change for those with harsh inner critics. If you’re constantly beating yourself up, then silencing your inner critic might do you some good.

But because I understand the science behind the power of positive thinking and positive self-talk and leverage it whenever possible—which is to say almost always—my inner voice relentlessly compliments me, praises my every move, credits me for the smallest accomplishment, and constantly cheers me on.

It’s outrageous and ridiculous.

Loathsome, even, if you could hear it.

Happily, I possess an inner monologue.

Thankfully, I’m the only person who can hear it.